Christmastide

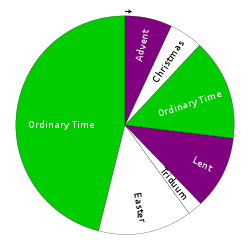

Christmastide (also known as Christmastime or the Christmas season) is a season of the liturgical year in most Christian churches. In some Christian denominations, Christmastide is identical to Twelvetide, a similar concept.

For most Christian denominations, such as the Roman Catholic Church and the United Methodist Church, Christmastide begins on 24 December at sunset or Vespers, which is liturgically the beginning of Christmas Eve.[1][2][3] Most of 24 December is thus not part of Christmastide, but of Advent, the season in the Church Year that precedes Christmastide. In many liturgical calendars, Christmastide is followed at sunset on 5 January by the closely related season of Epiphanytide.

There are several celebrations within Christmastide, including Christmas Day (25 December), St. Stephen's Day (26 December), Childermas (28 December), New Year's Eve (31 December), the Feast of the Circumcision of Christ or the Solemnity of Mary, Mother of God (1 January), and the Feast of the Holy Family (date varies). The Twelve Days of Christmas terminate with Epiphany Eve or Twelfth Night (the evening of 5 January).[4]

Customs of the Christmas season include carol singing, gift giving, attending Nativity plays, and church services,[5] and eating special food, such as Christmas cake. Traditional examples of Christmas greetings include the Western Christian phrase "Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year!" and the Eastern Christian greeting "Christ is born!", to which others respond, "Glorify Him!"[6][7]

Dates

Christmastide begins at sunset on 24 December. Historically, the ending of Christmastide was sunset on 6 January. This traditional date is still followed by the Anglican Church and Lutheran Church, where Christmastide, commonly called the Twelve Days of Christmas, lasts 12 days, from 25 December to 5 January, the latter date being named as Twelfth Night.[8]

However, the ending is defined differently by some Christian denominations.[9] In 1969, the Roman Rite of the Catholic Church expanded Christmastide by a variable number of days: "Christmas Time runs from... up to and including the Sunday after Epiphany or after 6 January."[10] Before 1955, the 12 Christmastide days in the Roman Rite (25 December to 5 January) were followed by the 8 days of the Octave of Epiphany, 6–13 January, and its 1960 Code of Rubrics defined "Christmastide" as running "from I vespers of Christmas to none of 5th January inclusive".[11]

History

| Christian liturgical year |

|---|

| Western |

| Eastern |

|

| East Syriac Rite |

|

In 567, the Council of Tours "proclaimed the twelve days from Christmas to Epiphany as a sacred and festive season, and established the duty of Advent fasting in preparation for the feast."[12][13][14][15][16][17] Christopher Hill, as well as William J. Federer, states that this was done in order to solve the "administrative problem for the Roman Empire as it tried to coordinate the solar Julian calendar with the lunar calendars of its provinces in the east."[18][19][20] Ronald Hutton adds that, while the Council of Tours declared the 12 days one festal cycle, it confirmed that three of those days were fasting days, dividing the rejoicing days into two blocs.[21] The Council held at Tours also spoke of a three-day fast at the beginning of January as an ancient custom, and ordered monks to observe it.[22]

According to the text of the acts of the 567 Council of Tours, edited by Jean Hardouin, Philippe Labbé, and Gabriel Cossart and published by the Royal Printers in Paris in 1714, the only mention of the period between Christmas and Epiphany made by that council is in its 17th canon.[23] In that canon, which dealt with the fasts to be observed by monks,[24] the council decreed:

De ieiuniis ... In Augusto, quia quotidie missae sanctorum sunt, prandium habeant. ... De Decembri usque ad natale Domini, omni die ieiunent. Et quia inter natale Domini et epiphania omni die festivitates sunt, itemque prandebunt. Excipitur triduum illud, quo ad calcandam gentilium consuetudinem, patres nostri statuerunt privatas in Kalendis Ianuarii fieri litanias. (On fasting ... In August, because each day there are Masses of the saints, let them have a full meal. ... In December until Christmas, they are to fast each day. Since between the Nativity of the Lord and Epiphany there are feasts on each day, they shall have a full meal, except during the three-day period on which our Fathers established private litanies for the beginning of January, in order to tread down the custom of the Gentiles.)

In medieval era Christendom, Christmastide "lasted from the Nativity to the Purification."[25][26] To this day, the "Christian cultures in Western Europe and Latin America extend the season to forty days, ending on the Feast of the Presentation of Jesus in the Temple and the Purification of Mary on 2 February, a feast also known as Candlemas because of the blessing of candles on this day, inspired by the Song of Simeon, which proclaims Jesus as 'a light for revelation to the nations'."[27] Many Churches refer to the period after the traditional Twelve Days of Christmas and up to Candlemas, as Epiphanytide, also called the Epiphany season.[28][29]

Traditions

During the Christmas season, various festivities are traditionally enjoyed and buildings are adorned with Christmas decorations, which are often set up during Advent.[30][31] These Christmas decorations include the Nativity Scene, Christmas tree, and various Christmas ornaments. In the Western Christian world, the two traditional days on which Christmas decorations are removed are Twelfth Night and Candlemas. Any not removed on the first occasion should be left undisturbed until the second.[32] Leaving the decorations up beyond Candlemas is considered to be inauspicious.[33]

On Christmas Eve or Christmas Day (the first day of Christmastide), it is customary for most households in Christendom to attend a service of worship or Mass.[34][35] During the season of Christmastide, in many Christian households, a gift is given for each of the Twelve Days of Christmastide, while in others, gifts are only given on Christmas Day or Twelfth Night, the first and last days of the festive season, respectively.[36] The practice of giving gifts during Christmastide, according to Christian tradition, is symbolic of the presentation of the gifts by the Three Wise Men to the infant Jesus.[37]

In several parts of the world, it is common to have a large family feast on Christmas Day, preceded by saying grace. Desserts such as Christmas cake are unique to Christmastide; in India, a version known as Allahabadi cake is popular.[38] During the Christmas season, it is also very common for Christmas carols to be sung at Christian churches, as well as in front of houses—in the latter scenario, groups of Christians go from one house to another to sing Christmas carols.[39] Popular Christmas carols include "Silent Night", "Come, Thou Long Expected Jesus", "We Three Kings", "Down in Yon Forest", "Away in a Manger", "I Wonder as I Wander", "God Rest Ye Merry, Gentlemen", "There's a Song in the Air", and "Let all mortal flesh keep silence".[40] In the Christmas season, it is very common for television stations to air feature films relating to Christmas and Christianity in general, such as The Greatest Story Ever Told and Scrooge.[41]

On Saint Stephen's Day, the second day of Christmastide,[42] people traditionally have their horses blessed,[43] and on the Feast of Saint John the Evangelist, the third day of Christmastide,[44] wine is blessed and consumed.[43] Throughout the twelve days of Christmastide, many people view Nativity plays,[45] among other forms of "musical and theatrical presentations".[43]

In the Russia Orthodox Church, Christmastide is referred to as "Svyatki", meaning "Holy Days". It is celebrated from the Nativity of Christ (7 January n.s) to the Theophany or Baptism of Christ (19 January n.s.). Activities during this period include attending church services, singing Christmas carols and spiritual hymns, visiting relatives and friends, and performing works of mercy, such as visiting the sick, the elderly people, orphans, and giving generous alms.[46] Since the fall of the Soviet Union, Babouschka, a character similar to the Italian Befana, has returned as a continued favorite of the Russian Christmas traditions.[47]

Liturgy

Western Christianity

.jpg)

Readings

| Calendar Day | Feast | Revised Common Lectionary | Roman Lectionary |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 December | Christmas Eve | Isaiah 9:2–7 Psalm 96 (11) Titus 2:11–14 Luke 2:1–14 [15–20] |

Is 62:1–5 Acts 13:16–17, 22-25/Mt 1:1–25 or 1:18–25 |

| 25 December | Christmas Day (first day of Christmastide) | Isaiah 52:7–10 Psalm 98 (3) Hebrews 1:1–4 [5–12] John 1:1–14 |

Is 52:7-10/Heb 1:1-6/Jn 1:1–18 or 1:1–5, 9–14 |

| 26 December | Saint Stephen's Day (second day of Christmastide) | 2 Chronicles 24:17–22 Psalm 17:1–9, 15 (6) Acts 6:8—7:2a, 51–60 Matthew 23:34–39 |

Acts 6:8–10; 7:54-59/Mt 10:17–22 |

| 27 December | Feast of St John the Apostle (third day of Christmastide) | Genesis 1:1–5, 26–31 Psalm 116:12–19 1 John 1:1--2:2 John 21:20–25 |

1 Jn 1:1-4/Jn 20:1a, 2–8 |

| 28 December | Feast of the Holy Innocents (fourth day of Christmastide) | Jeremiah 31:15–17 Psalm 124 (7) 1 Peter 4:12–19 Matthew 2:13–18 |

1 Jn 1:5—2:2/Mt 2:13–18 |

| 29 December | Feast of Saint Thomas Becket (fifth day of Christmastide) | 1 Chronicles 28:1–10 1 Corinthians 3:10–17 Psalm 147:12–20 |

1 Jn 2:3-11/Lk 2:22–35 |

| 30 December | First Sunday of Christmastide (sixth day of Christmastide) | 1 Samuel 2:18–20, 26 Psalm 148 Colossians 3:12–17 Luke 2:41–52 |

Sir 3:2–6, 12-14/Col 3:12–21 or 3:12-17/Lk 2:41–52 1 Sm 1:20–22, 24-28/1 Jn 3:1–2, 21-24/Lk 2:41–52 (Year C) |

| 31 December | Saint Sylvester's Day / New Year's Eve (cf. watchnight service) (seventh day of Christmastide) | Ecclesiastes 3:1–13 Psalm 8 Revelation 21:1-6a Matthew 25:31–46 |

1 Jn 2:18-21/Jn 1:1–18 |

| 1 January | Feast of the Circumcision of Christ (Lutheran and Anglican Churches) Solemnity of Mary, Mother of God (Catholic Church) (eighth day of Christmastide) |

Numbers 6:22–27 Psalm 8 Galatians 4:4–7 Philippians 2:5–11 (alternate) Luke 2:15–21 |

Nm 6:22-27/Gal 4:4-7/Lk 2:16–21 (18) |

| 2 January | (ninth day of Christmastide) | Proverbs 1:1–7 James 3:13–18 Psalm 147:12–20 |

1 Jn 2:22-28/Jn 1:19–28 |

| 3 January | (tenth day of Christmastide) | Job 42:10–17 Luke 8:16–21 Psalm 72 |

1 Jn 2:29—3:6/Jn 1:29–34 |

| 4 January | (eleventh day of Christmastide) | Isaiah 6:1–5 Acts 7:44–53 Psalm 72 |

1 Jn 3:7-10/Jn 1:35–42 (207) |

| 5 January | Twelfth Night (twelfth day of Christmastide) | Jeremiah 31:7–14 John 1:[1-9] 10–18 Psalm 72 |

1 Jn 3:11-21/Jn 1:43–51 (208) |

Eastern Christianity

In the Eastern Orthodox Church, as well as in the Greek Catholic Churches and Byzatine-Rite Lutheran Churches, Christmas is the third most important feast (after Pascha and Pentecost). The day after, the Church celebrates the Synaxis of the Theotokos. This means that Saint Stephen's Day and the Feast of the Holy Innocents fall one day later than in the West. The coming of the Wise Men is celebrated on the feast itself.

Suppression by antireligious governments

Revolutionary France

With the atheistic Cult of Reason in power during the era of Revolutionary France, Christian Christmas religious services were banned and the three kings cake of the Christmas-Epiphany season was forcibly renamed the "equality cake" under anticlerical government policies.[49][50]

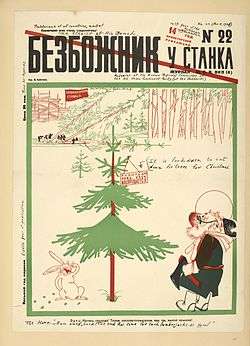

Soviet Union

Under the state atheism of the Soviet Union, after its foundation in 1917, Christmas celebrations—along with other Christian holidays—were prohibited. Saint Nicholas was replaced by Dyed Moroz or Grandfather Frost, the Russian Spirit of Winter who brought gifts on New Year's, accompanied by the snowmaiden Snyegurochka who helps distribute gifts.[47]

It was not until the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 that the persecution ended and Christmas was celebrated for the first time in Russia after seven decades.[51] Russia had adopted the custom of celebrating New Year's Day instead. However, the Orthodox Church Christmas is on 7 January. This is, also, an official national holiday.[47]

Nazi Germany

European History Professor Joseph Perry wrote that in Nazi Germany, "because Nazi ideologues saw organized religion as an enemy of the totalitarian state, propagandists sought to deemphasize—or eliminate altogether—the Christian aspects of the holiday" and that "Propagandists tirelessly promoted numerous Nazified Christmas songs, which replaced Christian themes with the regime's racial ideologies."[52]

People's Republic of China

The government of the People's Republic of China officially espouses state atheism,[53] and has conducted antireligious campaigns to this end.[54] In December 2018, officials raided Christian churches just prior to Christmastide and coerced them to close; Christmas trees and Santa Clauses were also forcibly removed.[55][56][57] Christmas in Modern China is celebrated only as a commercial day and very much secular and is not a public holiday.

References

- Hickman, Hoyt Leon (1 April 1984). United Methodist Altars. Abingdon Press. ISBN 978-0-68742985-1. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

Christmas eve: Begins at sunset December 24 and is part of Christmas, since the days of the Christian year traditionally begin at sunset the previous day.

- "Introduction to Christmas Season". General Board of Discipleship (GBOD). The United Methodist Church. 2013. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

Christmas is a season of praise and thanksgiving for the incarnation of God in Jesus Christ, which begins with Christmas Eve (December 24 after sundown) or Day and continues through the Day of Epiphany. The name Christmas comes from the season's first service, the Christ Mass. Epiphany comes from the Greek word epiphania, which means "manifestation." New Year's Eve or Day is often celebrated in the United Methodist tradition with a Covenant Renewal Service. In addition to acts and services of worship for the Christmas Season on the following pages, see The Great Thanksgivings and the scripture readings for the Christmas Season in the lectionary.... Signs of the season include a Chrismon tree, a nativity scene (include the magi on the Day of Epiphany), a Christmas star, angels, poinsettias, and roses.

- Hickman, Hoyt Leon (1 April 1984). United Methodist Altars. Abingdon Press. ISBN 978-0-68742985-1. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

Christmas Season: From sunset December 24 through January 6. The season celebrating the birth and manifestation (epiphany) of Christ.

- Wickham, Glynne (5 September 2013). Plays and their Makers up to 1576. Routledge. p. 42. ISBN 9781136288975.

Again, however, the feasts appointed to follow Christmas [Day] like those following Easter are all celebrations: St Stephen (26 December), St John the Evangelist (27 December), Holy Innocents (28 December), Circumcision (1 January) and Epiphany (6 January). Collectively they make up the Twelve Days of Christmas, terminating with Twelfth Night.

- Bharati, Agehanada (1 January 1976). Ideas and Actions. Walter de Gruyter. p. 454. ISBN 9783110805871.

These were services of worship held in Christian churches at Christmastide...

- Dice, Elizabeth A. (2009). Christmas and Hanukkah. Infobase Publishing. p. 47. ISBN 9781438119717.

The meal begins with the Lord's Prayer, traditionally led by the father of the family. A prayer of thanksgiving for all the blessings of the past year is said and then prayers for the good things in the coming year are offered. The head of the family greets those present with the traditional Christmas greeting: "Christ is Born!" The family members respond: "Glorify Him!"

- Ruprecht, Tony (14 December 2010). Toronto's Many Faces. Dundurn. p. 412. ISBN 9781459718050.

The majority of Ukrainians celebrate Christmas on January 7, with the highlight being the eve, January 6. A Holy Supper of 12 meatless dishes is served in memory of the 12 apostles, and begins when the children see the first star in the evening sky. The father offers a prayer which is followed by the traditional Christmas greeting, "Christ is born." The family respons with, "Let us glorify Him."

- Bratcher, Dennis (10 October 2014). "The Christmas Season". Christian Resource Institute. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

...the actual Christmas Season in most Western church traditions begins at sunset on Christmas Eve, December 24, and lasts through January 5. Since this time includes 12 days, the season of Christmas is known in many places as the Twelve Days of Christmas.

- Truscott, Jeffrey A. Worship. Armour Publishing. p. 103. ISBN 978-981430541-9.

As with the Easter cycle, churches today celebrate the Christmas cycle in different ways. Practically all Protestants observe Christmas itself, with services on 25 December or the evening before. Anglicans, Lutherans and other churches that use the ecumenical Revised Common Lectionary will likely observe the four Sundays of Advent, maintaining the ancient emphasis on the eschatological (First Sunday), ascetic (Second and Third Sundays), and scriptural/historical (Fourth Sunday). Besides Christmas Eve/Day, they will observe a 12-day season of Christmas from 25 December to 5 January.

- "Universal Norms on the Liturgical Year, 33" (PDF). Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- "Murphy, Patrick L., English translation of the 1960 Code of Rubrics" (PDF). Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- Fr. Francis X. Weiser. "Feast of the Nativity". Catholic Culture.

The Council of Tours (567) proclaimed the twelve days from Christmas to Epiphany as a sacred and festive season, and established the duty of Advent fasting in preparation for the feast. The Council of Braga (563) forbade fasting on Christmas Day.

- Fox, Adam (19 December 2003). "'Tis the season". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

Around the year 400 the feasts of St Stephen, John the Evangelist and the Holy Innocents were added on succeeding days, and in 567 the Council of Tours ratified the enduring 12-day cycle between the nativity and the epiphany.

- Forbes, Bruce David (1 October 2008). Christmas: A Candid History. University of California Press. p. 27. ISBN 9780520258020.

In 567 the Council of Tours proclaimed that the entire period between Christmas and Epiphany should be considered part of the celebration, creating what became known as the twelve days of Christmas, or what the English called Christmastide. On the last of the twelve days, called Twelfth Night, various cultures developed a wide range of additional special festivities. The variation extends even to the issue of how to count the days. If Christmas Day is the first of the twelve days, then Twelfth Night would be on January 5, the eve of Epiphany. If December 26, the day after Christmas, is the first day, then Twelfth Night falls on January 6, the evening of Epiphany itself. After Christmas and Epiphany were in place, on December 25 and January 6, with the twelve days of Christmas in between, Christians gradually added a period called Advent, as a time of spiritual preparation leading up to Christmas.

- Hynes, Mary Ellen (1993). Companion to the Calendar. Liturgy Training Publications. p. 8. ISBN 9781568540115.

In the year 567 the church council of Tours called the 13 days between December 25 and January 6 a festival season.

- Martindale, Cyril Charles (1908). "Christmas". The Catholic Encyclopedia. New Advent. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

The Second Council of Tours (can. xi, xvii) proclaims, in 566 or 567, the sanctity of the "twelve days" from Christmas to Epiphany, and the duty of Advent fast; …and that of Braga (563) forbids fasting on Christmas Day. Popular merry-making, however, so increased that the "Laws of King Cnut", fabricated c. 1110, order a fast from Christmas to Epiphany.

- Bunson, Matthew (21 October 2007). "Origins of Christmas and Easter holidays". Eternal Word Television Network (EWTN). Retrieved 17 December 2014.

The Council of Tours (567) decreed the 12 days from Christmas to Epiphany to be sacred and especially joyous, thus setting the stage for the celebration of the Lord’s birth...

- Hill, Christopher (2003). Holidays and Holy Nights: Celebrating Twelve Seasonal Festivals of the Christian Year. Quest Books. p. 91. ISBN 9780835608107.

This arrangement became an administrative problem for the Roman Empire as it tried to coordinate the solar Julian calendar with the lunar calendars of its provinces in the east. While the Romans could roughly match the months in the two systems, the four cardinal points of the solar year—the two equinoxes and solstices—still fell on different dates. By the time of the first century, the calendar date of the winter solstice in Egypt and Palestine was eleven to twelve days later than the date in Rome. As a result the Incarnation came to be celebrated on different days in different parts of the Empire. The Western Church, in its desire to be universal, eventually took them both—one became Christmas, one Epiphany—with a resulting twelve days in between. Over time this hiatus became invested with specific Christian meaning. The Church gradually filled these days with saints, some connected to the birth narratives in Gospels (Holy Innocents' Day, December 28, in honor of the infants slaughtered by Herod; St. John the Evangelist, "the Beloved," December 27; St. Stephen, the first Christian martyr, December 26; the Holy Family, December 31; the Virgin Mary, January 1). In 567, the Council of Tours declared the twelve days between Christmas and Epiphany to become one unified festal cycle.

- Federer, William J. (6 January 2014). "On the 12th Day of Christmas". American Minute. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

In 567 AD, the Council of Tours ended a dispute. Western Europe celebrated Christmas, December 25, as the holiest day of the season... but Eastern Europe celebrated Epiphany, January 6, recalling the Wise Men's visit and Jesus' baptism. It could not be decided which day was holier, so the Council made all 12 days from December 25 to January 6 "holy days" or "holidays," These became known as "The Twelve Days of Christmas."

- Kirk Cameron, William Federer (6 November 2014). Praise the Lord. Trinity Broadcasting Network. Event occurs at 01:15:14. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

Western Europe celebrated Christmas December 25 as the holiest day. Eastern Europe celebrated January 6 the Epiphany, the visit of the Wise Men, as the holiest day... and so they had this council and they decided to make all twelve days from December 25 to January 6 the Twelve Days of Christmas.

- Hutton, Ronald (2001). Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191578427. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

In 567 the council of Tours declared that the whole period of twelve days between the Nativity and Epiphany formed one festal cycle. It also confirmed that three of those days, representing the old Kalendae, would be kept as fasts between two blocs of rejoicing.

- Dues, Greg (2008). Advent and Christmas. Twenty-Third Publications. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-58595722-4. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

January 1 has had many religious themes in Christian history. None of them are associated with the secular understanding of New Year's Day so popular in our society today. At first the day was celebrated as special because it was the Octave of Christmas and, so to speak, a repeat of that day and theme. The church promoted penitential liturgies and fasting to offset the influence of pagan New Year's boisterous practices. In the year 567, the Second Council of Tours prescribed a three-day fast to correspond with the first days of the new year.

- "Jean Hardouin, Philippe Labbé, Gabriel Cossart (editors), Acta Conciliorum et Epistolae Decretales (Typographia Regia, Paris, 1714), pp. 355–368". Books.google.com. 15 October 2010. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- Dowden, John (1910). The Church Year and Kalendar. Cambridge University Press. Archived from the original on 22 December 2014. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

From the Sermons of Augustine we learn that in his time Jan. 1 was observed by Christians as a solemn fast, in protest against the licentious revelry and excesses of the pagans at this time of the year (Serm. 197, 198) And as late as the Second Council of Tours (a.d. 567) it is enjoined that, while all other days between the Nativity and the Epiphany are to be treated (in regard to use of food) as festivals, an exception is to be made for the space of three days at the beginning of January, for which time the fathers had appointed litanies to be made 'ad calcandam Gentilium consuetudinem.' But it should be remarked that the canon (17) dealing with the subject has special reference to fasts to be observed by monks. It is therefore not impossible that the fast had by this time ceased to be observed by the general body of the faithful, but, in a spirit of conservatism, was regarded as proper to be maintained in the monasteries.

-

Annals of St. Joseph. Norbertine Fathers. 1935. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

CHRISTMASTIDE OF OLD In medieval days Christmas lasted from the Nativity to the Purification. No one ever thought of removing the holly and the ivy until after the day of Our Lord's Presentation in the Temple.

-

Phan, Peter C.; Brancatelli, Robert J. (2005). The Directory on Popular Piety and the Liturgy: Principles and Guidelines – A Commentary. Liturgical Press. p. 82. ISBN 9780814628935. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

The feast of the Presentation of the Lord originated in the East and was known as the feast of the Purification of Our lady until 1969, falling forty days after Christmas and serving as the traditional end of Christmastide.

- Senn, Frank C. (2012). Introduction to Christian Liturgy. Fortress Press. p. 120. ISBN 9781451424331.

- Bratcher, Dennis (6 January 2014). "The Season of Epiphany". Christian Resource Institute (CRI). Archived from the original on 29 October 2014. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

Christmas begins with Christmas Day December 25 and lasts for Twelve Days until Epiphany, January 6, which looks ahead to the mission of the church to the world in light of the Nativity. The one or two Sundays between Christmas Day and Epiphany are sometimes called Christmastide.... For many Protestant church traditions, the season of Epiphany extends from January 6th until Ash Wednesday, which begins the season of Lent leading to Easter. Depending on the timing of Easter, this longer period of Epiphany includes from four to nine Sundays. Other traditions, especially the Roman Catholic tradition, observe Epiphany as a single day, with the Sundays following Epiphany counted as Ordinary Time.

- Atwell, Robert (28 June 2013). The Good Worship Guide: Leading Liturgy Well. Hymns Ancient and Modern Ltd. p. 212. ISBN 9781853117190.

The Christmas-Epiphany Season, celebrating the Incarnation of our Lord, begins with Evening Prayer on Christmas Eve and finishes after Evening Prayer on the Feast of the Presentation of Christ in the Temple (Candlemas) when Simeon and Anna greet the child Jesus and recognize him as the long-awaited Messiah. Christmastide lasts 12 days, with the Feast of the Epiphany (The Manifestation of Christ to the Gentiles) celebrating on 6 January.

- Michelin (10 October 2012). Germany Green Guide Michelin 2012–2013. Michelin. p. 73. ISBN 9782067182110.

Advent – The four weeks before Christmas are celebrated by counting down the days with an advent calendar, hanging up Christmas decorations and lightning an additional candle every Sunday on the four-candle advent wreath.

- Normark, Helena (1997). "Modern Christmas". Graphic Garden. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

Christmas in Sweden starts with Advent, which is the await for the arrival of Jesus... Most people start putting up the Christmas decorations on the first of Advent.

- "Candlemas". British Broadcasting Corporation. 16 September 2009. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

Any Christmas decorations not taken down by Twelfth Night (January 5th) should be left up until Candlemas Day and then taken down.

- Raedisch, Linda (1 October 2013). The Old Magic of Christmas: Yuletide Traditions for the Darkest Days of the Year. Llewellyn Publications. p. 161. ISBN 9780738734507. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- Aloian, Molly (30 September 2008). Christmas. Crabtree Publishing Company. p. 17. ISBN 9780778742876.

Going to Church Christmas Eve is a special time for many people...Churches usually have candlelight services or midnight masses.

- Altar (1885). Before The Altar. p. 25. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

The Church orders you to receive at least three times a year, of which one time is to be Easter, the other two presumably Christmas and Whitsuntide.

- Kubesh, Katie; McNeil, Niki; Bellotto, Kimm. The 12 Days of Christmas. In the Hands of a Child. p. 16.

The Twelve Days of Christmas, also called Twelvetide, are also associated with festivities that begin on the evening of Christmas Day and last through the morning of Epiphany. This period is also called Christmastide ... one early American tradition was to make a wreath on Christmas Eve and hang it on the front door on Christmas night. The wreath stayed on the front door through Epiphany. Some families also baked a special cake for the Epiphany. Other Old Time Traditions from around the world include: Giving gifts on Christmas night only. Giving gifts on the Twelfth Night only. Giving gifts on each night. On the Twelfth Night, a Twelfth Night Cake or King Cake is served with a bean or pea baked in it. The person who finds the bean or pea in his or her portion is a King of Queen for the day.

- Bash, Anthony; Bash, Melanie (22 November 2012). Inside the Christmas Story. A&C Black. p. 132. ISBN 9781441121585.

Popular tradition has it that there were three Magi because they presented three gifts to Jesus out of their treasure chests...The presentation of the gifts is supposed to be the origin of the practice of giving Christmas presents.

- Nair, Malini (15 December 2013). "Cakewalk in Allahabad". The Times of India. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

Around early December, an unusual kind of pilgrim starts to take the Prayag Raj from Delhi to Allahabad: the devout worshipper of the Allahabadi Christmas cake. This is no elegant western pudding — it is redolent with desi ghee, petha, ginger, nutmeg, javitri, saunf, cinnamon, something called cake ka jeera and marmalades from Loknath ki Galli. All this is browned to perfection at a bakery that has acquired cult status — Bushy's on Kanpur Road.

- Geddes, Gordon; Griffiths, Jane (2002). Christian Belief and Practice. Heinemann. p. 102. ISBN 9780435306915.

Carol singing is a common custom during the Christmas season. Many Christians form groups and go from house to house singing carols.

- Parker, David (2005). Christmas and Charles Dickens. AMS Press. ISBN 9780404644642.

- Newman, Jay (1 January 1996). Religion Vs. Television: Competitors in Cultural Context. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 101. ISBN 9780275956400.

Then, of course, television regularly presents motion pictures (including made-for-television movies) and dramatic specials whose religious subjects or themes are so pronounced that they clearly qualify as religious television programs. One may immediately call to mind the Biblical epics of Cecil B. Demille, more sophisticated if somewhat ponderous films like The Song of Bernadette, The Robe, The Inn of the Sixth Happiness, and The Greatest Story Ever Told, and lighter but in some ways more moving films like Green Pastures, Here Comes Mr. Jordan, and Going My Way. These are but a few of the dramatic shows built around religious subjects and themes that commercial and public television stations in North America regularly deliver to their audiences. Although television news coverage of religion is essentially news programming and is not primarily inspired by religious motives, some of its offerrings do represent a kind of religious television programming, such as the outwardly pious features presented during the Christmas and Easter seasons...

- Lopez, Jadwiga (1 January 1977). Christmas in Scandinavia. World Book Encyclopedia. ISBN 9780716620037.

December 26 is a legal holiday, and is called "Second Day Christmas.” It is also St. Stephen's Day— the feast day of a Christian missionary, once a stable boy, who came to Sweden around A.D. 1050.

- Walsh, Joseph J. (2001). Were They Wise Men Or Kings?: The Book of Christmas Questions. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 99. ISBN 9780664223120.

Wine would be blessed (and much of it drunk) on St. John's Day, and horses would be blessed on St. Stephen's Day. But above all, the days were dedicated to revelry and idleness. In some places the houses of the gentry were supposed to stay open to locals for the whole twelve days, although not everyone was so generous. Great feasting and drinking went on for these twelve days, and many artistic performances, as well, for the season was also known for its musical and theatrical presentations.

- Frandsen, Mary E. (4 April 2006). Crossing Confessional Boundaries : The Patronage of Italian Sacred Music in Seventeenth-Century Dresden. Oxford University Press. p. 161. ISBN 9780195346367.

On the Feast of St. John the Evangelist (the third day of Christmas) in 1665, for example, peranda presented two concertos in the morning service, his O Jesu mi dulcissime and Verbum caro factum est, and presented his Jesus dulcis, Jesu pie and Atendite fideles at Vespers.

- Martin, Charles Basil (1959). The Survivals of Medieval Religious Drama in New Mexico. University of Missouri Press. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- "Chizhenko, Andrei. "Christmastide: What is the Season and How are we to spend it?", Pravoslavie, 2017". Pravoslavie.ru. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- DeLaine, Linda. "Christmastide Tradition", Russian Life Magazine

- Harper, Timothy (1999). Moscow Madness: Crime, Corruption, and One Man's Pursuit of Profit in the New Russia. McGraw-Hill. p. 72. ISBN 9780070267008.

- Christmas in France. World Book Encyclopedia. 1996. p. 35. ISBN 9780716608769.

Carols were altered by substituting names of prominent political leaders for royal characters in the lyrics, such as the Three Kings. Church bells were melted down for their bronze to increase the national treasury, and religious services were banned on Christmas Day. The cake of kings, too, came under attack as a symbol of the royalty. It survived, however, for a while with a new name—the cake of equality.

- Mason, Julia (21 December 2015). "Why Was Christmas Renamed 'Dog Day' During the French Revolution?". HistoryBuff. Archived from the original on 1 November 2016. Retrieved 31 October 2016.

How did people celebrate the Christmas during the French Revolution? In white-knuckled terror behind closed doors. Anti-clericalism reached its apex on 10 November 1793, when a Fête de la Raison was held in honor of the Cult of Reason. Churches across France were renamed "Temples of Reason" and the Notre Dame was "de-baptized" for the occasion. The Commune spared no expense: "The first festival of reason, which took place in Notre Dame, featured a fabricated mountain, with a temple of philosophy at its summit and a script borrowed from an opera libretto. At the sound of Marie-Joseph Chénier‘s Hymne à la Liberté, two rows of young women, dressed in white, descended the mountain, crossing each other before the ‘altar of reason’ before ascending once more to greet the goddess of Liberty." As you can probably gather from the above description, 1793 was not a great time to celebrate Christmas in the capital.

- Goldberg, Carey (7 January 1991). "A Russian Christmas—Better Late Than Never : Soviet Union: Orthodox Church celebration is the first under Communists. But, as with most of Yeltsin's pronouncements, the holiday stirs a controversy". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

For the first time in more than seven decades, Christmas—celebrated today by Russian Orthodox Christians—is a full state holiday across Russia's vast and snowy expanse. As part of Russian Federation President Boris N. Yeltsin's ambitious plan to revive the traditions of Old Russia, the republic's legislature declared last month that Christmas, long ignored under atheist Communist ideology, should be written back into the public calendar.

- Perry, Joseph (24 December 2015). "How the Nazis co-opted Christmas: A history of propaganda". The Washington Post. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- Dillon, Michael (2001). Religious Minorities and China. Minority Rights Group International.

- Buang, Sa'eda; Chew, Phyllis Ghim-Lian (9 May 2014). Muslim Education in the 21st Century: Asian Perspectives. Routledge. p. 75. ISBN 9781317815006.

Subsequently, a new China was found on the basis of Communist ideology, i.e. atheism. Within the framework of this ideology, religion was treated as a 'contorted' world-view and people believed that religion would necessarily disappear at the end, along with the development of human society. A series of anti-religious campaigns was implemented by the Chinese Communist Party from the early 1950s to the late 1970s. As a result, in nearly 30 years between the beginning of the 1950s and the end of the 1970s, mosques (as well as churches and Chinese temples) were shut down and Imams involved in forced 're-education'.

- Holl, Daniel (20 December 2018). "Chinese City Cuts Down Christmas". The Epoch Times.

City law enforcement officials were ordered to “crack down on street-side Christmas trees, Santa Clauses and anything related to Christmas,” said the memo. “Completely control the use of park-squares and other public spaces against promoting religious propaganda activities.” Communism, being officially atheist, has long been at odds with anything related to faith or religion, and Christmas has long since been a target. Other far-left political groups, including the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), and even the Nazi Party, suppressed Christmas related activities.

- "Alarm over China's Church crackdown". BBC. 18 December 2018.

Among those arrested are a prominent pastor and his wife, of the Early Rain Covenant Church in Sichuan. Both have been charged with state subversion. And on Saturday morning, dozens of police raided a children's Bible class at Rongguili Church in Guangzhou. One Christian in Chengdu told the BBC: "I'm lucky they haven't found me yet." China is officially atheist, though says it allows religious freedom.

- "Santa Claus won't be coming to this town, as Chinese officials ban Christmas". South China Morning Post. 18 December 2018.

Christmas is not a recognised holiday in mainland China – where the ruling party is officially atheist – and for many years authorities have taken a tough stance on anyone who celebrates it in public. ... The statement by Langfang officials said that anyone caught selling Christmas trees, wreaths, stockings or Santa Claus figures in the city would be punished. ... While the ban on the sale of Christmas goods might appear to be directed at retailers, it also comes amid a crackdown on Christians practising their religion across the country. On Saturday morning, more than 60 police officers and officials stormed a children’s Bible class in Guangzhou, capital of southern China’s Guangdong province. The incident came after authorities shut down the 1,500-member Zion Church in Beijing in September and Chengdu’s 500-member Early Rain Covenant Church last week. In the case of the latter, about 100 worshippers were snatched from their homes or from the streets in coordinated raids.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Christmastide. |