Hephthalites

The Hephthalites (Bactrian: ηβοδαλο, Ebodalo), sometimes called the White Huns,[6][7] were a people who lived in Central Asia and South Asia during the 5th to 8th centuries. Militarily important during 450 to 560, they were based in Bactria and expanded east to the Tarim Basin, west to Sogdia and south through Afghanistan to Pakistan and parts of northern India. They were a tribal confederation and included both nomadic and settled urban communities. They were part of the four major states known collectively as Xyon (Xionites) or Huna, being preceded by the Kidarites, and succeeded by the Alkhon and lastly the Nezak. All of these peoples have often been linked to the Huns who invaded Eastern Europe during the same period, and/or have been referred to as "Huns", but there is no consensus among scholars about such a connection.

Hephthalites | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 440s–710 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tamga of the Hephthalites

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

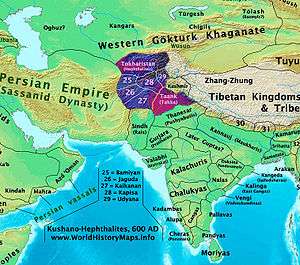

The Hephthalites (green), c. 500. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Nomadic empire | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Late Antiquity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Established | 440s | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 710 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The stronghold of the Hephthalites was Tokharistan on the northern slopes of the Hindu Kush, in what is present-day northeastern Afghanistan. By 479, the Hephthalites had conquered Sogdia and driven the Kidarites westwards, and by 493 they had captured parts of present-day Dzungaria and the Tarim Basin in what is now Northwest China. They expanded into Pakistan as well.[8]

The sources for Hephthalite history are poor and historians' opinions differ. There is no king-list and historians are not sure how they arose or what language they spoke. The Sveta Huna who invaded Pakistan are probably the Hephthalites, but the exact relation is not clear. They seem to have called themselves Ebodalo (ηβοδαλο, hence Hephthal), often abbreviated Eb (ηβ), a name they wrote in the Bactrian script on some of their coins.[9][10][11][12] The origin of the name "Hephthalites" is unknown, possibly from either a Khotanese word *Hitala meaning "Strong" or from postulated Middle Persian *haft āl "the Seven".[13]

Name and ethnonyms

The name Hephthalites originated with Ancient Greek sources, which also referred to them as Ephthalite, Abdel or Avdel.

To the Armenians, the Hephthalites were Haital, to the Persians and Arabs, they were Haytal or Hayatila (هياطلة), while their Bactrian name was Ebodalo (ηβοδαλο).[3]

In Chinese chronicles, the Hephthalites are usually called Ye-tha-i-li-to 厌带夷栗陁 (pinyin: Yàndàiyílìtuó), or the more usual modern and abbreviated form Yada 嚈噠 (pinyin: Yèdā). The latter name has been given various Latinised renderings, including Yeda, Ye-ta, Ye-tha; Ye-dā and Yanda. The corresponding Cantonese and Korean names Yipdaat and Yeoptal (Korean: 엽달), which preserve aspects of the Middle Chinese pronunciation (roughly yep-daht, [ʔjɛpdɑt]) better than the modern Mandarin pronunciation, are more consistent with the Greek Hephthalite. Some Chinese chroniclers suggest that the root Hephtha- (as in Ye-ta-i-li-to or Yada) was technically a title equivalent to "emperor", while Hua was the name of the dominant tribe.[15]

In Ancient India, names such as Hephthalite were unknown. The Hephthalites were apparently part of, or offshoots of, people known in India as Hunas or Turushkas,[16] although these names may have referred to broader groups or neighbouring peoples. Ancient Sanskrit text Pravishyasutra mentions a group of people named Havitaras but it is unclear whether the term denotes Hephthalites.[17]

Origins

There are several theories regarding the origins of the Hephthalites, with the Iranian[19][20][21][22] and Turkic[23][24] theories being the most prominent.

According to most specialist scholars, the spoken language of the Hephthalites was an Eastern Iranian language, but different from the Bactrian language written in the Greek alphabet that was used as their "official language" and minted on coins, as was done under the preceding Kushan Empire.[25][26][27]

According to Xavier Tremblay, one of the Hephthalite rulers was named "Khingila", which has the same root as the Sogdian word xnγr and the Wakhi word xiŋgār, meaning "sword". The name Mihirakula is thought to be derived from mithra-kula which is Iranian for "the Sun family". Toramāna, Mihirakula's father, is also considered to have an Iranian origin. In Sanskrit, mihira-kula would mean the kul "family" of mihira "Sun", although mihira is not purely Sanskrit but is a borrowing from Middle Iranian mihr.[28] Janos Harmatta gives the translation "Mithra's Begotten" and also supports the Iranian theory.[29]

For many years scholars suggested that they were of Turkic stock.[24] Some have claimed that some groups amongst the Hephthalites were Turkic-speakers.[23] Today, however, the Hephthalites are generally held to have been an Eastern Iranian people speaking an East Iranian language.[32] The Hephthalites inscribed their coins in the Bactrian (Iranian) script,[33] held Iranian titles,[33] the names of Hephthalite rulers given in Ferdowsi's Shahnameh are Iranian,[33] and gem inscriptions and other evidence shows that the official language of the Hephthalite elite was East Iranian.[33] In 1959, Kazuo Enoki proposed that the Hephthalites were probably Indo-European (East) Iranians as some sources indicated that they were originally from Bactria, which is known to have been inhabited by Indo-Iranian people in antiquity.[25] Richard Frye is cautiously accepting of Enoki's hypothesis, while at the same time stressing that the Hephthalites "were probably a mixed horde".[34] More recently Xavier Tremblay's detailed examination of surviving Hephthalite personal names has indicated that Enoki's hypothesis that they were East Iranian may well be correct, but the matter remains unresolved in academic circles.[26]

According to the Encyclopaedia Iranica and Encyclopaedia of Islam, the Hephthalites possibly originated in what is today Afghanistan.[35][36] They apparently had no direct connection with the European Huns, but may have been causally related with their movement. The tribes in question deliberately called themselves "Huns" in order to frighten their enemies.[37]

Some Hephthalites may have been a prominent tribe or clan of the Chionites. According to Richard Nelson Frye:

Just as later nomadic empires were confederations of many peoples, we may tentatively propose that the ruling groups of these invaders were, or at least included, Turkic-speaking tribesmen from the east and north. Although most probably the bulk of the people in the confederation of Chionites and then Hephhtalites spoke an Iranian language... this was the last time in the history of Central Asia that Iranian-speaking nomads played any role; hereafter all nomads would speak Turkic languages and the millennium-old division between settled Tajik and nomadic Turk would obtain.[38]

The 6th-century Byzantine historian Procopius of Caesarea (History of the Wars, Book I. ch. 3), related them to the Huns in Europe:

The Ephthalitae Huns, who are called White Huns [...] The Ephthalitae are of the stock of the Huns in fact as well as in name, however they do not mingle with any of the Huns known to us, for they occupy a land neither adjoining nor even very near to them; but their territory lies immediately to the north of Persia [...] They are not nomads like the other Hunnic peoples, but for a long period have been established in a goodly land... They are the only ones among the Huns who have white bodies and countenances which are not ugly. It is also true that their manner of living is unlike that of their kinsmen, nor do they live a savage life as they do; but they are ruled by one king, and since they possess a lawful constitution, they observe right and justice in their dealings both with one another and with their neighbours, in no degree less than the Romans and the Persians[40]

As an illustration of how little we know of the Hephthalites, Aydogdy Kurbanov surveyed the literature and found these opinions: They were named after a king Eftalan or Hephtal. They lived in the Eftali valley (location not given). They called themselves War or Jabula or Alkhon. They were a political rather than ethnic unit. They, the Xionites and Kidarites were the same people or three different peoples. They were the ruling class of the Xionites. They were not Xionites. They were not the "White Huns". They were natives of Bactria, or the Pamirs, or the Kundu Kush. They began as the Hua who were subjects of the Rouran in the Turfan area. They were a branch of the Yuezhi in the Altai area who merged with the Dinglings, defeated the Yueban and moved south. They arose near the Aral Sea from a fusion of Massagetae and Alans and moved southeast under the name of Xionites. They were partly Tibetan or Mongol or Tokharian or Huns who returned east after the fall of Attila.

Kurbanov presents a few other theories about Hephthalites' origins in imperial Chinese chronicles, and makes no attempt to reconcile them.[41]

- They were descendants of the Jushi from Turfan;

- They were descendants of the Greater Yuezhi tribes who remained behind after the rest of the people fled the Xiongnu;

- They were descendants of the Kangju;

- They were descendants of the Gaoche.

Chinese chronicles state that they were originally a tribe of the Yuezhi, living to the north of the Great Wall in Dzungaria,[24] and subject to the Rouran (Jwen-Jwen), as were some Turkic peoples at the time. Their original name was Hoa or Hoa-tun; subsequently they named themselves Ye-tha-i-li-to (厌带夷栗陁, or more briefly Ye-tha 嚈噠),[42] after their royal family, which descended from one of the five Yuezhi families which also included the Kushan.

The Hephthalite was a vassal state to the Rouran Khaganate until the beginning of the 5th century.[43] Between Hephthalites and Rourans were also close contacts, although they had different languages and cultures, and Hephthalites borrowed much of their political organization from Rourans.[3] In particular, the title "Khan", which according to McGovern was original to the Rourans, was borrowed by the Hephthalite rulers.[3] The reason for the migration of the Hephthalites southeast was to avoid a pressure of the Rourans. Further, the Hephthalites defeated the Yuezhi in Bactria and their leader Kidara led the Yuezhi to the south.[3]

History

Territory

The Hephthalites formed in Bactria around 450, or sometime before.[8] In 442 their tribes were fighting the Persians. Around 451 they pushed southeast to Gandhara. In 456 a Hephthalite embassy arrived in China. By 458 they were strong enough to intervene in Persia.

Around 466 they probably took Transoxianan lands from the Kidarites with Persian help but soon took from Persia the area of Balkh and eastern Kushanshahr.

In the second half of the fifth century they controlled the deserts of Turkmenistan as far as the Caspian Sea and possibly Merv.[45]

By 500 they held the whole of Bactria and the Pamirs and parts of Afghanistan.

Probably in the late fifth century they took the western Tarim Basin (Kashgar and Khotan) and in 479 they took the east end (Turfan). In 497–509, they pushed north of Turfan to the Urumchi region. In 509 they took 'Sughd' (the capital of Sogdiana).

Around 557 their empire was destroyed by an alliance of the Göktürks and the Sasanians, but some of them remained as local rulers in the Afghan region for the next 150 years.

5th century: conflicts and alliances with the Sasanians

The Hephthalites were originally vassals of the Rouran Khaganate but split from their overlords in the early fifth century. The next time they were mentioned was in Persian sources as foes of Yazdegerd II (435–457), who from 442, fought 'tribes of the Hephthalites', according to the Armenian Elisee Vardaped.

In 453, Yazdegerd moved his court east to deal with the Hephthalites or related groups.

In 458, a Hephthalite king called Khushnavaz helped the Sasanian Emperor Peroz I (458–484) gain the Persian throne from his brother.[46]

The Hephthalites may have also helped the Sasanians to eliminate another Hunnic tribe, the Kidarites: by 467, Peroz I, with Hephthalite aid, reportedly managed to capture Balaam and put an end to Kidarite rule in Transoxiana once and for all.[47] The weakened Kidarites had to take refuge in the area of Gandhara.

Later however, Peroz I fought three wars with his former allies the Hephthalites. In the first two he himself was captured and ransomed.[30] In the third, at the Battle of Herat (484), he was killed, and for the next two years the Hephthalites plundered parts of Persia.[46]

With the Sasanian Empire paying tribute to the Hephthalites, from 474, the Hephthalites themselves adopted the winged, triple-crescent crown of Peroz I to crown their effigy in their own coinage.[30] They thus expressed symbolically that they had become the legitimate rulers of Iran.[30]

From 484 until the middle of the sixth century, Persia paid tribute to the Hephthalites.

In 488, Kavadh I (488–496, 498–531) made himself king of Persia with Hephthalite help. (He overthrew his uncle, the brother of Peroz).

In 496–498, Kavadh I was overthrown by the nobles and clergy, escaped and restored himself with a Hephthalite army. Hephthalite troops helped Kavadh at a siege of Edessa.[46]

6th century and later

The period c. 498–555 is almost blank in the standard English sources. In 552, the Göktürks took over Mongolia, and by 558 reached the Volga. By 581 or before, the western part separated and became the Western Turkic Khaganate.

Circa 555–567,[49] the Turks and the Persians allied against the Hephthalites and defeated them after an eight-day battle near Qarshi, the Battle of Bukhara, perhaps in 557.[50] The allies then fought each other and c. 571 drew a border along the Oxus. After the battle, the Hephthalites withdrew to Bactria and replaced king Gatfar with Faghanish, the ruler of Chaghaniyan. What happened in the Tarim Basin is not clear.

Invasion of the Sasanid Empire (7th century)

Circa 600, the Hephthalites were raiding the Sasanian Empire as far as Spahan in central Iran. The Hephthalites issued numerous coins imitating the coinage of Khosrow II, adding on the obverse a Hephthalite signature in Sogdian and Tamgha symbol. In ca. 606/607, Khosrow recalled Smbat IV Bagratuni from Persian Armenia and sent him to Iran to repel the Hephthalites. Smbat, with the aid of a Persian prince named Datoyean, repelled the Hephthalites from Persia, and plundered their domains in eastern Khorasan, where Smbat is said to have killed their king in single combat.[52] Khosrow then gave Smbat the honorific title Khosrow Shun ("the Joy or Satisfaction of Khosrow"),[52] while his son Varaztirots II Bagratuni received the honorific name Javitean Khosrow ("Eternal Khosrow").[52]

Decline

Small Hephthalite states remained, paying tribute either to the Turks or the Persians. They are reported in the Zarafshan valley, Chaghaniyan, Khuttal, Termez, Balkh, Badghis, Herat and Kabul.[53] Circa 651, during the Arab conquest, the ruler of Badghis was involved in the fall of the last Sassanian Shah Yazdegerd III. Circa 705, the Hephthalite rulers of Badghis and Chaghaniyan surrendered to the Arabs under Qutaiba ibn Muslim. Some remnants, not necessarily dynastic, of the Hephthalite confederation would be incorporated into the Göktürks, as an Old Tibetan document, dated to the 8th century, mentioned the tribe Heb-dal among 12 Dru-gu tribes ruled by Qapaghan Qaghan[54]

Religion and culture

They were said to practice polyandry and artificial cranial deformation. Chinese sources said they worshiped 'foreign gods', 'demons', the 'heaven god' or the 'fire god'. The Gokturks told the Byzantines that they had walled cities. Some Chinese sources said that they had no cities and lived in tents. Litvinsky tries to resolve this by saying that they were nomads who moved into the cities they had conquered. There were some government officials but central control was weak and local dynasties paid tribute.[55]

According to Song Yun, the Chinese Buddhist monk who visited the Hephthalite territory in 540 and "provides accurate accounts of the people, their clothing, the empresses and court procedures and traditions of the people and he states the Hephthalites did not recognize the Buddhist religion and they preached pseudo gods, and killed animals for their meat."[2] It is reported that some Hephthalites often destroyed Buddhist monasteries but these were rebuilt by others. According to Xuanzang, the third Chinese pilgrim who visited the same areas as Song Yun about 100 years later, the capital of Chaghaniyan had five monasteries.[33]

According to historian André Wink, "...in the Hephthalite dominion Buddhism was predominant but there was also a religious sediment of Zoroastrianism and Manichaeism."[4] Balkh had some 100 Buddhist monasteries and 30,000 monks. Outside the town was a large Buddhist monastery, later known as Naubahar.[33]

There were Christians among the Hephthalites by the mid-6th century, although nothing is known of how they were converted. In 549, they sent a delegation to Aba I, the patriarch of the Church of the East, asking him to consecrate a priest chosen by them as their bishop, which the patriarch did. The new bishop then performed obeisance to both the patriarch and the Sasanian king, Khosrow I. The seat of the bishopric is not known, but it may be the Badghis–Qadištan whose bishop Gabriel sent a delegate to the synod of Patriarch Ishoyahb I in 585.[56] It was probably placed under the metropolitan of Herat. The church's presence among the Hephthalites enabled them to expand their missionary work across the Oxus. In 591, some Hephthalites serving in the army of the rebel Bahram Chobin were captured by Khosrow II and sent to the Roman emperor Maurice as a diplomatic gift. They had Nestorian crosses tattooed on their foreheads.[5][57]

Hephthalites or "White Huns" in Southern Central Asia

It is not clear whether the people called Hunas, or Sveta Huna (White Huns) in Sanskrit were the Hephthalites or a related people, the Xionites. In the northwest of the Indian subcontinent, the Hephthalites were not distinguished from their immediate Chionite predecessors; both are known as Huna (Sanskrit: Sveta-Hūna, White Huns). In Ancient India, names such as Hephthalite were unknown. The Hephthalites were apparently part of, or offshoots of, people known in India as Hunas or Turushkas.[16]

Historians such as Beckwith, referring to Étienne de la Vaissière, say that the Hephthalites were not necessarily one and the same as the Hunas (Sveta Huna).[58] According to de la Vaissiere, the Hephthalites are not directly identified in classical sources alongside that of the Hunas.[59]

The Huna had already established themselves in Afghanistan and the modern province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa of Pakistan by the first half of the 5th century, and the Gupta emperor Skandagupta had repelled a Hūna invasion in 455 before the Hephthalite clan came along. These attacks on the Guptas were therefore probably made by the predecessors of the Hephthalites, the Kidarites.

India was invaded during the 5th century by a people known in the Indian Subcontinent as the Hunas – including the Alchon Huns and possibly an alliance broader than the Hephthalites and/or Xionites. The Hunas were initially defeated by Emperor Skandagupta of the Gupta Empire.[60] By the end of the 5th century, however, the Hunas had overrun the part of the Gupta Empire that was to their southeast and had conquered Central and North India.[3] Gupta Emperor Bhanugupta defeated the Hunas under Toramana in 510.[61][62] The Hunas were driven out of India by the kings Yasodharman and Narasimhagupta, during the early 6th century.[63][64]

The Hephthalites had their capital at Badian, modern Kunduz, but the emperor lived in the capital city for just three winter months, and for the rest of the year, the government seat would move from one locality to another like a camp.[3] The Hephthalites continued the pressure on ancient India's northwest frontier and broke east by the end of the 5th century, hastening the disintegration of the Gupta Empire. They made their capital at the city of Sakala, modern Sialkot in Pakistan, under their Emperor Mihirakula. But later the Huns were defeated and driven out of India by the Indian kings Yasodharman and Narasimhagupta in the 6th century.

Possible descendants

A number of groups may have descended from the Hephthalites.[65][66]

- Pashtuns: The Hephthalites may have contributed to the ethnogenesis of Pashtuns. Yu. V. Gankovsky, a Soviet historian on Afghanistan, stated: "Pashtun began as a union of largely East Iranian tribes, which became the initial ethnic stratum of the Pashtun ethnogenesis dating from the middle of the first millennium CE, and is connected with the dissolution of the Hephthalite confederacy."[67]

- Durrani: The Durrani Pashtuns of Afghanistan were called "Abdali" before 1747. According to linguist Georg Morgenstierne, their tribal name Abdālī may have "something to do with" the Hephthalite.[68] This hypothesis was endorsed by historian Aydogdy Kurbanov, who indicated that after the collapse of the Hephthalite confederacy, they likely assimilated into different local populations and that the Abdali may be one of the tribes of Hephthalite origin.[69]

- Khalaj: The Khalaj people are first mentioned in the 7th–9th centuries in the area of Ghazni, Qalati Ghilji, and Zabulistan in present-day Afghanistan. They spoke Khalaj Turkic. Al-Khwarizmi mentioned them as a remnant tribe of the Hephthalites. However, according to linguist Sims-Williams, archaeological documents do not support the suggestion that the Khalaj were the Hephthalites' successors,[70] while according to historian V. Minorsky, the Khalaj were "perhaps only politically associated with the Hephthalites." Some of the Khalaj were later Pashtunized, after which they transformed into the Pashtun Ghilji tribe.[71]

- Kanjina: a Saka tribe linked to the Indo-Iranian Kumijis[72][73] and incorporated into the Hephthalites. Kanjinas were possibly Turkicized later, as indicated by al-Khwarizmi. However, Bosworth and Clauson contended that al-Khwarizmi was simply using "Turks" "in the vague and inaccurate sense".[74]

- Karluks: (or Qarlughids) were reported as settled in Ghazni and Zabulistan, present-day Afghanistan, in the thirteenth century. Many Muslim geographers identified "Karluks" Khallukh ~ Kharlukh with "Khalajes" Khalaj from confusion, as the two names were similar and these two groups dwelt near each other.[75][76]

- Abdal is a name associated with the Hephthalites. It is an alternate name for the Äynu people of the Tarim Basin and appears as a sub-tribe of the Chowdur Turkmen, Kazakhs and Volga Bulgars. Abdals are also present in Turkey.

- Rajputs: The Rajputs may have begun as assimilation of Hephthalites in Indian society.[66][77]

See also

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Central Asia | ||||||||||||||||||

.jpg) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Ancient | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Middle Ages | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Colonization period | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Great game period | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Topics | ||||||||||||||||||

References

- Bivar, A. D. H. "HEPHTHALITES". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- "Chinese Travelers in Afghanistan". Abdul Hai Habibi. alamahabibi.com. 1969. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- A.Kurbanov "THE HEPHTHALITES-ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL ANALYSIS" 2010

- Al-Hind, the Making of the Indo-Islamic World: Early medieval India. André Wink, p. 110. E. J. Brill.

- David Wilmshurst, The Martyred Church: A History of the Church of the East (East and West Publishing, 2011), pp. 77–78.

- Dignas, Assistant Professor of History Beate; Dignas, Beate; Winter, Engelbert (2007). Rome and Persia in Late Antiquity: Neighbours and Rivals. Cambridge University Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-521-84925-8.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2009). The Fall Of The West: The Death Of The Roman Superpower. Orion. ISBN 978-0-297-85760-0.

- The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Attila, Michael Maas p.287

- Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017). ReOrienting the Sasanians: East Iran in Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press. p. 213. ISBN 9781474400312.

- Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017). ReOrienting the Sasanians: East Iran in Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press. p. 217. ISBN 9781474400312.

- Whitfield, Susan (2018). Silk, Slaves, and Stupas: Material Culture of the Silk Road. Univ of California Press. p. 185. ISBN 9780520957664.

- ALRAM, MICHAEL (2014). "From the Sasanians to the Huns New Numismatic Evidence from the Hindu Kush". The Numismatic Chronicle (1966-). 174: 278–279. ISSN 0078-2696. JSTOR 44710198.

- Kurbanov p. 27

- Dani, Ahmad Hasan; Litvinsky, B. A. (1996). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The crossroads of civilizations, A.D. 250 to 750. UNESCO. pp. 136–137. ISBN 9789231032110.

- Enoki, K. "The Liang shih-kung-t'u on the origin and migration of the Hua or Ephthalites," Journal of the Oriental Society of Australia 7:1–2 (December 1970):37–45

- History of Buddhism in Afghanistan, Alexander Berzin, Study Buddhism

- Dinesh Prasad Saklani (1998). Ancient Communities of the Himalaya. Indus Publishing. p. 187. ISBN 978-81-7387-090-3.

- CNG Coins

-

- Denis Sinor (1990). The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, volume 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521243049. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

"The relative abundance of data norwithstanding, we have but a very fragmentary picture of Hephthalite civilization.There is no consensus con- cerning the Hephthalite language, though most scholars seem to think that it was Iranian.The Pei shih at least clearly states that the language of the Hephthalites differs from those of the High Chariots, of the Juan-juan and of the "various Hu a rather vague term which, in this context, probably refers to some Iranian peoples... According to the Liang shu the Hephthalites worshiped Heaven and also fire a clear reference to Zoroastrianism."

- University of Indiana (1954). "Asia Major, volume 4, part 1". Institute of History and Philology of the Academia Sinica. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

"Concerning the Hephthalites, Enoki Kazuo stresses that their place of origin was to the north of the Hindu Kush mountain range and that they were of Iranian stock he rejects the view that they were of Altaic origin, with Turkish connections."

- Robert L. Canfield (2002). Turko-Persia in Historical Perspective. Cambridge University Press P. 272.pp.49. ISBN 9780521522915. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

"One cannot go into details here about that dark period of Central Asian history from the time of the Kushans down the coming of the Arabs, but one may suggest that the beginning of this period saw the last waves of Iranian-speaking nomads moving to the south, to be replaced by the Turkic-speaking nomads beginning in the late fourth century.... but our information about them, known in Classical and Islamic sources as the Chionites and Hephthalites, is so meager that much confusion has reigned regarding their origins and nature.Just as later nomadic empires were confederations of many peoples, we may tentatively propose that the ruling groups of these were, or at least included, Turkic-speaking tribesmen from the east and north, although most probably the bulk of the people in the confederation ofChionites and then Hephthalites spoke an Iranian language.In this case, as normal, the nomads adopted the written language, institutions, and culture of the settled folk.To call them "Iranian Huns" as Gobl has done is not infelicitous, for surely the bulk of the population ruled by the Chionites and Hephthalites was lranian (Gobl 1967:ix). But this was the last time in the history ofCentral Asia that Iranian-speaking nomads played any role; hereafter all nomads would speak Turkic languages and the millennium-old division between settled Tajik and nomadic Turk would obtain."

- Denis Sinor (1990). The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, volume 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521243049. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- M. A. Shaban, "Khurasan at the Time of the Arab Conquest", in Iran and Islam, in memory of Vlademir Minorsky, Edinburgh University Press, (1971), p481; ISBN 0-85224-200-X.

- "The White Huns – The Hephthalites", Silk Road

- Enoki Kazuo, "On the nationality of White Huns", 1955

- David Christian A History of Russia, Inner Asia and Mongolia (Oxford: Basil Blackwell) 1998 p248

- "White Huns", Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia

- Enoki, Kazuo: "On the Nationality of the White Huns", Memoirs of the Research Department of the Tokyo Bunko, 1959, No. 18, p. 56. Quote: "Let me recapitulate the foregoing. The grounds upon which the White Huns are assigned an Iranian tribe are: (1) that their original home was on the east frontier of Tokharestan; and (2) that their culture contained some Iranian elements. Naturally, the White Huns were sometimes regarded as another branch of the Kao-ch’e tribe by their contemporaries, and their manners and customs are represented as identical with those of the T’u-chueh, and it is a fact that they had several cultural elements in common with those of the nomadic Turkish tribes. Nevertheless, such similarity of manners and customs is an inevitable phenomenon arising from similarity of their environments. The White Huns could not be assigned as a Turkish tribe on account of this. The White Huns were considered by some scholars as an Aryanized tribe, but I would like to go further and acknowledge them as an Iranian tribe. Though my grounds, as stated above, are rather scarce, it is expected that the historical and linguistic materials concerning the White Huns are to be increased in the future and most of the newly-discovered materials seem to confirm my Iranian-tribe theory." here "On The Nationality of the Ephthalites" (PDF). Retrieved 1 April 2017. or "Hephtalites" or "On the Nationality of the Hephtalites".

- Xavier Tremblay (2001). "appendix D: Notes Sur L'Origine Des Hephtalites" (PDF). Pour une histore de la Sérinde. Le manichéisme parmi les peoples et religions d'Asie Centrale d'aprés les sources primaire (in French). Vienna. pp. 183–188. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

Malgré tous les auteurs qui, depuis KLAPROTH jusqu’ ALTHEIM in SuC, p113 sq et HAUSSIG, Die Geschichte Zentralasiens und der Seidenstrasse in vorislamischer Zeit, Darmstadt, 1983 (cf. n.7), ont vu dans les Huns Blancs des Turcs, l’explication de leurs noms par le turc ne s’impose jamais, est parfois impossible et n’est appuyée par aucun fait historique (aucune trace de la religion turque ancienne), celle par l’iranien est toujours possible, parfois évidente, surtout dans les noms longs comme Mihirakula, Toramana ou γοβοζοκο qui sont bien plus probants qu’ αλ- en Αλχαννο. Or l’iranien des noms des Huns Blancs n’est pas du bactrien et n’est donc pas imputable à leur installation en Bactriane [...] Une telle accumulation de probabilités suffit à conclure que, jusqu’à preuve du contraire, les Hepthalites étaient des Iraniens orientaux, mais non des Sogdiens.

; also available at http://www.azargoshnasp.net/history/Hephtalites/Hephtalites.htm - Denis Sinor, "The establishment and dissolution of the Türk empire" in Denis Sinor, "The Cambridge history of early Inner Asia, Volume 1", Cambridge University Press, 1990. p. 300:"There is no consensus concerning the Hephthalite language, though most scholars seem to think that it was Iranian."

- Jacques Duchesne-Guillemin, Congrès International d&Etud. Études mithriaques: actes du 2e Congrès International, Téhéran, du 1er au 8 september 1975. p 293. Retrieved 2012-9-5.

- Janos Harmatta, "The Rise of the Old Persian Empire: Cyrus the Great," AAASH (Acta Antiqua Acadamie Scientiarum Hungaricae) 19, 197, pp. 4–15.

- The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Attila by Michael Maas p.287

- CNG Coins

- West 2009, pp. 274–277

- Unesco Staff 1996, pp. 135–163

- R. Frye, "Central Asia in pre-Islamic Times" Archived 15 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopaedia Iranica

- G. Ambros/P.A. Andrews/L. Bazin/A. Gökalp/B. Flemming and others, "Turks", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, Online Edition 2006

- A.D.H. Bivar, "Hephthalites", in Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition.

- M. Schottky, "Iranian Huns", in Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition

- Robert L. Canfield, Turko-Persia in Historical Perspective, Cambridge University Press, 1991, p. 49

- British Museum notice

- Procopius, History of the Wars. Book I, Ch. III, "The Persian War"

- Kurbanov pp2-32

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- Grousset (1970), p. 67.

- CNG Coins

- Kurbanov, p164; Merv p167.

- History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Ahmad Hasan Dani, B. A. Litvinsky, Unesco p.38ff

- Zeimal 1996, p. 130.

- Iaroslav Lebedynsky, "Les Nomades", p172.

- The war is variously dated. 560–565 (Gumilyov, 1967); 555 (Stark, 2008, Altturkenzeit, 210); 557 (Iranica, Khosrow ii); 558–561 (Iranica.hephthalites); 557–563 (Baumer, Hist. Cent. Asia, 2, 174); 557–561 (Sinor, 1990, Hist. Inner Asia, 301); 560–563 (UNESCO, Hist. Civs. C. A., iii, 143); 562– 565 (Christian, Hist. Russia, Mongolia, C. A., 252); c. 565 (Grousset,Empire Steppes, 1970, p. 82); 567 (Chavannes, 1903, Documents, 236 and 229)

- The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Attila, Michael Maas, Cambridge University Press, 2014 p.284sq

- CNG Coins

- Martindale, Jones & Morris (1992), pp. 1363–1364

- The Huns by Hyun Jin Kim, Routledge p.56

- Venturi, Federica (2008). "An Old Tibetan document on the Uighurs: A new translation and interpretation". Journal of Asian History. 1 (42): 21.

- Litvinsky, pp144-47

- Erica C. D. Hunter (1996), "The Church of the East in Central Asia", Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library of Manchester 78(3): 129–142, at 133–134.

- Mehmet Tezcan, "On 'Nestorian' Christianity Among the Hephthalites or the White Huns", in Li Tang and Dietmar W. Winkler (eds.), Artifact, Text, Context: Studies on Syriac Christianity in China and Central Asia (Lit Verlag, 2020), pp. 195–212.

- Empires of the Silk Road. 2009. p. 406.

- de la Vaissiere, Etienne. "Huns et Xiongnu". Central Asiatic Journal (49): 3–26.

- Ancient India: History and Culture by Balkrishna Govind Gokhale, p.69

- Ancient Indian History and Civilization by Sailendra Nath Sen, p.220

- Encyclopaedia of Indian Events and Dates by S. B. Bhattacherje, p.A15

- India: A History by John Keay, p.158

- History of India, in Nine Volumes: Vol. II by Vincent A. Smith, p.290

- Kurbanov pp238-243

- West, Barbara A. (2010). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. pp. 275–276. ISBN 978-1-4381-1913-7.

- Gankovsky, Yu. V., et al. A History of Afghanistan, Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1982, p. 382

- Morgenstierne, Georg. "The Linguistic Stratification of Afghanistan." Afghan Studies 2 (1979): 23–33.

- Kurbanov, Aydogdy. "The Hephthalites: Archaeological and Historical Analysis." PhD dissertation, Free University of Berlin, 2010.

- Bonasli, Sonel (2016). "The Khalaj and their language". Endagered Turkic Languages II A. Aralık: 273–275.

- The Khalaj West of the Oxus, by V. Minorsky: Khyber.ORG. Archived June 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine; excerpts from "The Turkish Dialect of the Khalaj", Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London, Vol 10, No 2, pp 417-437 (retrieved 10 January 2007).

- <Golden, Peter B. (1992). An Introduction to the History of the Turkic People. Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden. p. 83

- Bosworth, C.E. "The Rulers of Chaghāniyān in Early Islamic Times" Iran. Vol. 19 (1981), p. 20

- Bosworth, C.E.; Clauson, Gerard (1965). "Al-Xwārazmī on the Peoples of Central Asia". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland No. 1/2: 8–9.

- Golden, Peter B. (1992). An Introduction to the History of the Turkic People. Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden. p. 387

- Minorsky, V. "Commentary on Ḥudūd al-ʿĀlam's "§15. The Khallukh" and "§24. Khorasanian Marches" pp. 286, 347-348

- Frye, Richard Nelson (1984). The History of Ancient Iran. C.H.Beck. p. 349. ISBN 978-3-406-09397-5.

Sources

- B.A. Litvinsky, The Hephthalite Empire, 1996, in History of Civilizations in Central Asia, iii, p135-183

- Kurbanov, Aydogdy (2010). "The Hephthalites: Archaeological and Historical Analysis" (PDF). Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- Grignaschi, M. (1980). "La Chute De L'Empire Hephthalite Dans Les Sources Byzantines et Perses et Le Probleme Des Avar". Acta Antiqua Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, Tomus XXVIII. Budapest: Akademiai Kiado.

- Haussig, Hans Wilhelm (1983). Die Geschichte Zentralasiens und der Seidenstraße in vorislamischer Zeit. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. ISBN 3-534-07869-1.

- Theophylaktos Simokates. P. Schreiner (ed.). Geschichte.

- West, Barbara A. (1 January 2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1438119137. Retrieved 18 January 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zeimal, E. V. (1996). "The Kidarite kingdom in Central Asia". History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Volume III: The Crossroads of Civilizations: A.D. 250 to 750. Paris: UNESCO. pp. 119–135. ISBN 92-3-103211-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hephthalites. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Ephthalites. |

- "The Ethnonym Apar in the Turkish Inscriptions of the VIII. Century and Armenian Manuscripts" Dr. Mehmet Tezcan.

- The Anthropology of Yanda (Chinese) pdf

- The Silkroad Foundation

- Columbia Encyclopedia: Hephthalites

- Hephthalite coins

- Hephthalite History and Coins of the Kashmir Smast Kingdom- Waleed Ziad at the Wayback Machine (archived 27 October 2009)

- The Hephthalites of Central Asia – by Richard Heli (long article with a timeline)

- The Hephthalites at the Wayback Machine (archived 9 February 2005) Article archived from the University of Washington's Silk Road exhibition – has a slightly adapted form of the Richard Heli timeline.

- (pdf) The Ethnonym Apar in the Turkish Inscriptions of the VIII. Century and Armenian Manuscripts – Mehmet Tezcan

- iranicaonline hephthalites

- Records Relevant to the Hephthalites in Ancient Chinese Historical Works, collected by Yu Taishan (2016).