Hen Ogledd

Yr Hen Ogledd (Welsh pronunciation: [ər ˌheːn ˈɔɡlɛð]), in English the Old North, is the region of Northern England and the southern Scottish Lowlands inhabited by the Celtic Britons of sub-Roman Britain in the Early Middle Ages. Its denizens spoke a variety of the Brittonic language known as Cumbric. The Hen Ogledd was distinct from the parts of northern Britain inhabited by the Picts, Anglo-Saxons, and Scoti as well as from Wales, although the people of the Hen Ogledd were the same Brittonic stock as the Picts, Welsh and Cornish, and the region loomed large in Welsh literature and tradition for centuries after its kingdoms had disappeared.

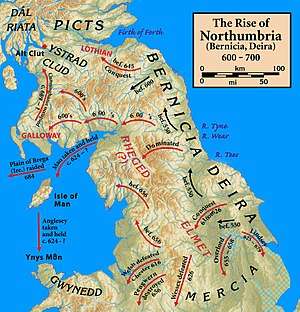

The major kingdoms of the Hen Ogledd were Elmet in western Yorkshire; Gododdin in Lothian and the Scottish Borders; Rheged, centred in Galloway; and Kingdom of Strathclyde, situated around the Firth of Clyde. Smaller kingdoms or districts included Aeron, Calchfynydd, Eidyn, Lleuddiniawn, and Manaw Gododdin; the last three were evidently parts of Gododdin. The Angle kingdoms of Deira and Bernicia both had Brittonic-derived names, suggesting they may have been Brittonic kingdoms in origin. All the kingdoms of the Old North except Strathclyde were conquered by Anglo-Saxons and Picts by about 800; Strathclyde was incorporated into the rising Middle Irish-speaking Kingdom of Scotland in the 11th century.

The legacy of the Hen Ogledd remained strong in Wales. Welsh tradition included genealogies of the Gwŷr y Gogledd, or Men of the North, and several important Welsh dynasties traced their lineage to them. A number of important early Welsh texts were attributed to the Men of the North, such as Taliesin, Aneirin, Myrddin Wyllt, and the Cynfeirdd poets. Heroes of the north such as Urien, Owain mab Urien, and Coel Hen and his descendants feature in Welsh poetry and the Welsh Triads.

Background

Almost nothing is reliably known of Central Britain before c. 550. There had never been a period of long-term, effective Roman control north of the Tyne–Solway line, and south of that line effective Roman control ended long before the traditionally given date of departure of the Roman military from Roman Britain in 407. It was noted in the writings of Ammianus Marcellinus and others that there was ever-decreasing Roman control from about AD 100 onward, and in the years after 360 there was widespread disorder and the large-scale permanent abandonment of territory by the Romans.

By 550, the region was controlled by native Brittonic-speaking peoples except for the eastern coastal areas, which were controlled by the Anglian peoples of Bernicia and Deira. To the north were the Picts (now also accepted as Brittonic speakers prior to Gaelicisation) with the Gaelic kingdom of Dál Riata to the northwest. All of these peoples would play a role in the history of the Old North.

Historical context

From a historical perspective, wars were frequently internecine, and Britons were aggressors as well as defenders, as was also true of the Angles, Picts, and Gaels. However, those Welsh stories of the Old North that tell of Briton fighting Anglian have a counterpart, told from the opposite side. The story of the demise of the kingdoms of the Old North is the story of the rise of the Kingdom of Northumbria from two coastal kingdoms to become the premier power in Britain north of the Humber and south of the Firth of Clyde and the Firth of Forth.

The interests of kingdoms of this era were not restricted to their immediate vicinity. Alliances were not made only within the same ethnic groups, nor were enmities restricted to nearby different ethnic groups. An alliance of Britons fought against another alliance of Britons at the Battle of Arfderydd. Áedán mac Gabráin of Dál Riata appears in the Bonedd Gwŷr y Gogledd, a genealogy among the pedigrees of the Men of the North.[1] The Historia Brittonum states that Oswiu, king of Northumbria, married a Briton who may have had some Pictish ancestry.[2][3] A marriage between the Northumbrian and Pictish royal families would produce the Pictish king Talorgan I. Áedán mac Gabráin fought as an ally of the Britons against the Northumbrians. Cadwallon ap Cadfan of the Kingdom of Gwynedd allied with Penda of Mercia to defeat Edwin of Northumbria.

Conquest and defeat did not necessarily mean the extirpation of one culture and its replacement by another. The Brittonic region of northwestern England was absorbed by Anglian Northumbria in the 7th century, yet it would re-emerge 300 years later as South Cumbria, joined with North Cumbria (Strathclyde) into a single state.

Societal context

The organisation of the Men of the North was tribal,[note 1] based on kinship groups of extended families, owing allegiance to a dominant "royal" family, sometimes indirectly through client relationships, and receiving protection in return. For Celtic peoples, this organisation was still in effect hundreds of years later, as shown in the Irish Brehon law, the Welsh Laws of Hywel Dda, and the Scottish Laws of the Brets and Scots. The Germanic Anglo-Saxon law had culturally different origins, but with many similarities to Celtic law. Like Celtic law, it was based on cultural tradition, without any perceivable debt to the Roman occupation of Britain.[note 2]

A primary royal court (Welsh: llys) would be maintained as a "capital", but it was not the bureaucratic administrative centre of modern society, nor the settlement or civitas of Roman rule. As the ruler and protector of his kingdom, the king would maintain multiple courts throughout his territory, travelling among them to exercise his authority and to address the needs of his clients, such as in the dispensing of justice. This ancient method of dispensing justice survived throughout England as a part of royal procedure until the reforms of Henry II (reigned 1154–1189) modernised the administration of law.

Language

Modern scholarship uses the term "Cumbric" for the Brittonic language spoken in the Hen Ogledd. It appears to have been very closely related to Old Welsh, with some local variances, and more distantly related to Cornish, Breton and the pre-Gaelic form of Pictish. There are no surviving texts written in the dialect; evidence for it comes from placenames, proper names in a few early inscriptions and later non-Cumbric sources, two terms in the Leges inter Brettos et Scottos, and the corpus of poetry by the cynfeirdd, the "early poets", nearly all of which deals with the north.[4]

The cynfeirdd poetry is the largest source of information, and it is generally accepted that some part of the corpus was first composed in the Old North.[4] However, it survives entirely in later manuscripts created in Wales, and it is unknown how faithful they are to the originals. Still, the texts do contain discernible variances that distinguish the speech from contemporary Welsh. In particular, these texts contain a number of archaisms – features that appear to have once been common in all Brittonic varieties, but which later vanished from Welsh and the Southwestern Brittonic languages.[4] In general, however, the differences appear to be slight, and the distinction between Cumbric and Old Welsh is largely geographical rather than linguistic.[5]

Cumbric gradually disappeared as the area was conquered by the Anglo-Saxons, and later the Scots and Norse, though it survived in the Kingdom of Strathclyde, centred at Alt Clut in what is now Dumbarton in Scotland. Kenneth H. Jackson suggested that it re-emerged in Cumbria in the 10th century, as Strathclyde established hegemony over that area. It is unknown when Cumbric finally became extinct, but the series of counting systems of Celtic origin recorded in Northern England since the 18th century have been proposed as evidence of a survival of elements of Cumbric;[5] though the view has been largely rejected on linguistic grounds, with evidence pointing to the fact that it was imported to England after the Old English era.[6][7]

Welsh interest

One of the traditional stories relating to the creation of Wales is derived from the arrival in Wales of Cunedda and his sons as "Men of the North". Cunedda himself is held to be the progenitor of the royal dynasty of the Kingdom of Gwynedd, one of the largest and most powerful of the medieval Welsh kingdoms, and an ongoing participant in the history of the Old North. Cunedda, incidentally, is represented as a descendant of one of Maximus' generals, Paternus, who Maximus appointed as commander at Alt Clut. However, the relationship between Wales and the Old North is more substantial than this one event, amounting to a self-perception that the Welsh and the Men of the North are one people. The modern Welsh term for themselves, Cymry, derives from this ancient relationship. It is not originally an ethnic or cultural term, and in the modern sense refers only to the Welsh of Wales and the Brittonic-speaking Men of the North.[8][9][10] However, it is the reflex of old kombrogoi, which meant simply "fellow-countrymen, Celts", and it is worth noting in passing that its Breton counterpart kenvroiz still has this original meaning "compatriots". The word began to be used as an endonym by the northern Britons during the early 7th century (and possibly earlier),[11] and was used throughout the Middle Ages to describe both the Kingdom of Strathclyde (the successor state to Ystrad Clud, known as North Cumbria, which flourished c. 900–1100) and western England north of the Ribble Estuary (South Cumbria). Before this, and for some centuries after, the traditional as well as the more literary term was Brythoniaid, recaIling the still older time when all Celts in the island remained a unity. Cymry survives today in the native name for Wales (Cymru, land of the Cymry), and in the English county name Cumbria, both meaning "homeland", "mother country".

Many of the traditional sources of information about the Old North are believed to have come to Wales from the Old North, and bards such as Aneirin (the reputed author of Y Gododdin) are thought to have been court poets in the Old North. These stories and bards are held to be no less Welsh than the stories and bards who were actually from Wales.

Nature of the sources

A listing of passages from the literary and historical sources, particularly relevant to the Old North, can be found in Sir Edward Anwyl's article Wales and the Britons of the North.[12] A somewhat dated introduction to the study of old Welsh poetry can be found in his 1904 article Prolegomena to the Study of Old Welsh Poetry.[13]

Literary sources

- The bardic poetry attributed to Taliesin, Aneirin, and Llywarch Hen.

- The genealogical tracts of the Harleian genealogies, the Bonedd Gwŷr y Gogledd, and the genealogies of Jesus College MS 20.

- The Triads of the Island of Britain (note that most of the triads published in the notorious third volume of The Myvyrian Archaiology of Wales are known to be the forgeries of Iolo Morganwg, and are not considered valid sources of historical information).[14] The standard scholarly edition is Trioedd Ynys Prydein by Rachel Bromwich.[15]

- The other elegies (Welsh: marwnadau) and songs of praise (Welsh: canu mawl), as well as certain mythological stories, that have been preserved.

Stories praising a patron and the construction of flattering genealogies are neither unbiased nor reliable sources of historically accurate information. However, while they may exaggerate and make apocryphal assertions, they do not falsify or change the historical facts that were known to the bards' listeners, as that would bring ridicule and disrepute to both the bards and their patrons. In addition, the existence of stories of defeat and tragedy, as well as stories of victory, lends additional credibility to their value as sources of history. Within that context, the stories contain useful information, much of it incidental, about an era of British history where very little is reliably known.

Historical sources

- The Historia Brittonum attributed to Nennius

- The Annales Cambriae

- The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

- The Ecclesiastical History of the English People by Bede

- The Annals of Tigernach

These sources are not without deficiencies. Both the authors and their later transcribers sometimes displayed a partisanship that promoted their own interests, portraying their own agendas in a positive light, always on the side of justice and moral rectitude. Facts in opposition to those agendas are sometimes omitted, and apocryphal entries are sometimes added.

While Bede was a Northumbrian partisan and spoke with prejudice against the native Britons, his Ecclesiastical History of the English People is highly regarded for its effort towards an accurate telling of history, and for its use of reliable sources. When passing along "traditional" information that lacks a historical foundation, Bede takes care to note it as such.[16]

The De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae by Gildas (c. 516–570) is occasionally relevant in that it mentions early people and places also mentioned in the literary and historical sources. The work was intended to preach Christianity to Gildas' contemporaries and was not meant to be a history. It is one of the few contemporary accounts of his era to have survived.

Place names

Cumbric place names in Scotland south of the Forth and Clyde, and in Cumberland and neighbouring counties, indicate areas of Hen Ogledd inhabited by Britons in the early Middle Ages.

Isolated locations of later British presence are also indicated by place names of Old English and Old Norse origin. In Yorkshire, the names of Walden, Walton and Walburn, from Old English walas "Britons or Welshmen", indicate Britons encountered by the Anglo-Saxons, and the name of Birkby, from Old Norse Breta "Britons", indicates a place where the Vikings met Britons.[17]

Dubious and fraudulent sources

The Historia Regum Britanniae of Geoffrey of Monmouth is disparaged as pseudohistory, though it looms large as a source for the largely fictional chivalric romance stories known collectively as the Matter of Britain. The lack of historical value attributed to the Historia lies only partly in the fact that it contains so many fictions and falsifications of history;[note 3] the fact that historical accuracy clearly was not a consideration in its creation makes any references to actual people and places no more than a literary convenience.

The Iolo Manuscripts are a collection of manuscripts presented in the early 19th century by Edward Williams, who is better known as Iolo Morganwg. Containing various tales, anecdotal material and elaborate genealogies that connect virtually everyone of note with everyone else of note (and with many connections to Arthur and Iolo's native region of Morgannwg), they were at first accepted as genuine, but have since been shown to be an assortment of forged or doctored manuscripts, transcriptions, and fantasies, mainly invented by Iolo himself. A list of works tainted by their reliance on the material presented by Iolo (sometimes without attribution) would be quite long.

Kingdoms and regions

Major kingdoms

Places in the Old North that are mentioned as kingdoms in the literary and historical sources include:

- Alt Clut or Ystrad Clud – a kingdom centred at what is now Dumbarton in Scotland. Later known as the Kingdom of Strathclyde, it was one of the best attested of the northern British kingdoms. It was also the last surviving, as it operated as an independent realm into the 11th century before it was finally absorbed by the Kingdom of Scotland.[21]

- Elmet – centred in western Yorkshire in northern England. It was located south of the other northern British kingdoms, and well east of present-day Wales, but managed to survive into the early 7th century.[22]

- Gododdin – a kingdom in what is now southeastern Scotland and northeastern England, the area previously noted as the territory of the Votadini. They are the subjects of the poem Y Gododdin, which memorialises a disastrous raid by an army raised by the Gododdin on the Angles of Bernicia.[23]

- Rheged – a major kingdom that evidently included parts of present-day Cumbria, though its full extent is unknown. It may have covered a vast area at one point, as it is very closely associated with its king Urien, whose name is tied to places all over northwestern Britain.[24]

Minor kingdoms and other regions

Several regions are mentioned in the sources, assumed to be notable regions within one of the kingdoms if not separate kingdoms themselves:

- Aeron – a minor kingdom mentioned in sources such as Y Gododdin, its location is uncertain, but several scholars have suggested that it was in the Ayrshire region of southwest Scotland.[25][26][27][28] It is frequently associated with Urien Rheged, and may have been part of his realm.[29]

- Calchfynydd ("Chalkmountain") – almost nothing is known about this area, though it was likely somewhere in the Hen Ogledd, as an evident ruler, Cadrawd Calchfynydd, is listed in the Bonedd Gwŷr y Gogledd. William Forbes Skene suggested an identification with Kelso (formerly Calchow) in the Scottish Borders.[30]

- Eidyn – this was the area around the modern city of Edinburgh, then known as Din Eidyn (Fort of Eidyn). It was closely associated with the Gododdin kingdom.[31] Kenneth H. Jackson argued strongly that Eidyn referred exclusively to Edinburgh,[32] but other scholars have taken it as a designation for the wider area.[33][34] The name may survive today in toponyms such as Edinburgh, Dunedin, and Carriden (from Caer Eidyn), located fifteen miles to the west.[35] Din Eidyn was besieged by the Angles in 638 and was under their control for most of the next three centuries.[31]

- Manaw Gododdin – the coastal area south of the Firth of Forth, and part of the territory of the Gododdin.[23] The name survives in Slamannan Moor and the village of Slamannan, in Stirlingshire.[36] This is derived from Sliabh Manann, the 'Moor of Manann'.[37] It also appears in the name of Dalmeny, some 5 miles northwest of Edinburgh, and formerly known as Dumanyn, assumed to be derived from Dun Manann.[37] The name also survives north of the Forth in Pictish Manaw as the name of the burgh of Clackmannan and the eponymous county of Clackmannanshire,[38] derived from Clach Manann, the 'stone of Manann',[37] referring to a monument stone located there.

- Novant – a kingdom mentioned in Y Gododdin, presumably related to the Iron Age Novantae tribe of southwestern Scotland.[39][40]

- Regio Dunutinga – a minor kingdom or region in North Yorkshire mentioned in the Life of Wilfrid. It was evidently named for a ruler named Dunaut, perhaps the Dunaut ap Pabo known from the genealogies.[41] Its name may survive in the modern town of Dent, Cumbria.[42]

Kingdoms that were not part of the Old North but are part of its history include:

- Dál Riata – Though this was a Gaelic kingdom, the family of Áedán mac Gabráin of Dál Riata appears in the Bonedd Gwŷr y Gogledd

- Northumbria and its predecessor states, Bernicia and Deira

- Pictish kingdom

Possible kingdoms

The following names appear in historical and literary sources, but it is unknown whether or not they refer to British kingdoms and regions of the Hen Ogledd.

- Bryneich – this is the British name for the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Bernicia. There was probably a pre-Saxon British kingdom in this area, but this is uncertain.[43]

- Deifr or Dewr – this was the British name for Anglo-Saxon Deira, a region between the River Tees and the Humber. The name is of British origin, but as with Bryneich it is unknown if it represented an earlier British kingdom.[44]

See also

- Wales in the Early Middle Ages

- Scotland in the Early Middle Ages

- History of Anglo-Saxon England

- England in the Middle Ages

- Northumbria

- Mercia

- Kingdom of Gwynedd

- Historical basis for King Arthur

- Cumbric language

- King Cole

Notes

- The tribal domains were called kingdoms and were led by a king, but were not organised nation-states in the modern (or ancient Roman) sense of the word. The kingdoms might grow and shrink based on the transitory fortunes of the leading tribe and royal family, with regional alliances and enmities playing a part in the resulting organisation. This organisation was applicable to southern Wales of the post-Roman era, where the royal inter-relationships of the kingdoms of Glywysing, Gwent, and Ergyng are so completely inter-twined that it is not possible to construct an independent history for any of them. When contention (i.e., war) occurred, it was between high-ranking individuals and their respective clients, in the manner of the contending House of Lancaster and House of York during the Wars of the Roses in the 15th century.

- "Anglo-Saxon law" is a modern neologism for the Saxon Law of Wessex, the Anglian Law of Mercia, and the Danelaw, all of which were sufficiently similar to merit inclusion within this umbrella term. The laws of Anglian Northumbria were supplanted by the Danelaw, but were certainly similar to these. The origins of English law have been much studied. For example, the 12th century Tractatus de legibus et consuetudinibus regni Angliae (Treatise on the laws and customs of the Kingdom of England) is the book of authority on English common law, and scholars have held that it owes a debt to Norman law and to Germanic law, and not to Roman law.

- Scholarly works by reputable authors, such as Lloyd's 1911 A History of Wales from the Earliest Times to the Edwardian Conquest, contain numerous citations of Geoffrey's fabrications of history, never citing him as a source of legitimate historical information.[18] More recent works of history tend to spend less energy on Geoffrey's Historia, merely ignoring him in passing. In Davies's 1990 A History of Wales, the first paragraph of page 1 discusses Geoffrey's prominence, after which he is occasionally mentioned as the source of historical inaccuracies and not as a source of legitimate historical information.[19] Earlier works might devote a few paragraphs detailing the proof that Geoffrey was the inventor of fictitious information, such as in James Parker's The Early History of Oxford, where persons such as Eldad, Eldod, Abbot Ambrius, and others are noted to be the result of Geoffrey's own imagination.[20]

Citations

- Bromwich 2006, pp. 256–257

- Nennius (800), "Genealogies of the Saxon kings of Northumbria", in Stevenson, Joseph (ed.), Nennii Historia Britonum, London: English Historical Society (published 1838), p. 50

- Nicholson, E. W. B. (1912), "The 'Annales Cambriae' and their so-called 'Exordium'", in Meyer, Kuno (ed.), Zeitschrift für Celtische Philologie, VIII, Halle: Max Niemeyer, p. 145

- Koch 2006, p. 516.

- Koch 2006, p. 517.

- A Dictionary of English Folklore, Jacqueline Simpson, Stephen Roud, Oxford University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-19-210019-X, 9780192100191, Shepeherd's score, pp. 271

- Margaret L. Faull, Local Historian 15:1 (1982), 21–3

- Lloyd 1911, pp. 191–192.

- Lloyd, John Edward (1912). A History of Wales from the Earliest Times to the Edwardian Conquest. Longmans, Green. p. 191.

- Phillimore, Egerton (1888), "Review of "A History of Ancient Tenures of Land in the Marches of North Wales"", in Phillimore, Egerton (ed.), Y Cymmrodor, IX, London: Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, pp. 368–371

- Phillimore, Egerton (1891), "Note (a) to The Settlement of Brittany", in Phillimore, Egerton (ed.), Y Cymmrodor, XI, London: Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion (published 1892), pp. 97–101

- Anwyl, Edward (July 1908 – April 1908), "Wales and the Britons of the North", The Celtic Review, IV, Edinburgh: Norman Macleod (published 1908), pp. 125–152, 249–273

- Anwyl, Edward (1904), "Prolegomena to the Study of Old Welsh Poetry", Transactions of the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion (Session 1903–1904), London: Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion (published 1905), pp. 59–83

- Lloyd 1911:122–123, Notes on the Historical Triads, in The History of Wales

- Rachel Bromwich (ed.), Trioedd Ynys Prydein (University of Wales Press, revised edition 1991) ISBN 0-7083-0690-X.

- For a recent view of Bede's treatment of Britons in his work, see W. Trent Foley and N.J. Higham, "Bede on the Britons." Early Medieval Europe 17.2 (2009): pp. 154–85.

- Jensen, Gillian Fellows (1978). "Place-Names and Settlement in the North Riding of Yorkshire". Northern History. 14 (1): 22–23. doi:10.1179/nhi.1978.14.1.19. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- Lloyd 1911, A History of Wales

- Davies 1990:1, A History of Wales

- Parker, James (1885), "Description of Oxford in Domesday Survey", The Early History of Oxford 727–1100, Oxford: Oxford Historical Society, p. 291

- Koch 2006, p. 1819.

- Koch 2006, pp. 670–671.

- Koch 2006, pp. 823–826.

- Koch 2006, pp. 1498–1499.

- Koch 2006, pp. 354–355; 904.

- Bromwich 1978, pp. 12–13; 157.

- Morris-Jones, pp. 75–77.

- Williams 1968, p. xlvii.

- Koch 2006, p. 1499.

- Bromwich 2006, p. 325.

- Koch 2006, pp. 623–625.

- Jackson 1969, pp. 77–78

- Williams 1972, p. 64.

- Chadwick, p. 107.

- Dumville, p. 297.

- Rhys, John (1904), "The Picts and Scots", Celtic Britain (3rd ed.), London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, p. 155

- Rhys, John (1901), "Place-Name Stories", Celtic Folklore: Welsh and Manx, II, Oxford: Oxford University, p. 550

- Rhys 1904:155, Celtic Britain, The Picts and the Scots.

- Koch 2006, pp. 824–825.

- Koch 1997, pp. lxxxii–lxxxiii.

- Koch 2006, p. 458.

- Koch 2006, p. 904.

- Koch 2006, pp. 302–304.

- Koch 2006, pp. 584–585.

References

- Bromwich, Rachel; Foster, Idris Llewelyn; Jones, R. Brinley (1978), Astudiaethau ar yr Hengerdd: Studies in Old Welsh Poetry, University of Wales Press, ISBN 0-7083-0696-9

- Bromwich, Rachel (2006), Trioedd Ynys Prydein: The Triads of the Island of Britain, University of Wales Press, ISBN 0-7083-1386-8

- Chadwick, Nora K. (1968), The British Heroic Age: the Welsh and the Men of the North, University of Wales Press, ISBN 0-7083-0465-6

- Davies, John (1990), A History of Wales (First ed.), London: Penguin Group (published 1993), ISBN 0-7139-9098-8

- Dumville, David (1994), "The eastern terminus of the Antonine Wall: 12th or 13th century evidence" (PDF), Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 124: 293–298, retrieved 7 September 2011.

- Jackson, Kenneth Hurlstone (1953), Language and History in Early Britain: A chronological survey of the Brittonic languages, first to twelfth century A.D., Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press

- Jackson, Kenneth H. (1969), The Gododdin: The Oldest Scottish Poem, Edinburgh University Press

- Koch, John T. (1997), The Gododdin of Aneirin: Text and Context from Dark-Age North Britain, University of Wales Press, ISBN 0-7083-1374-4

- Koch, John T. (2006), Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0

- Lloyd, John Edward (1911), A History of Wales from the Earliest Times to the Edwardian Conquest, I (Second ed.), London: Longmans, Green, and Co. (published 1912)

- Morris-Jones, John (1918), "Taliesin", Y Cymmrodor, Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, 28, retrieved 1 December 2010.

- Williams, Ifor (1968), The Poems of Taliesin: Volume 3 of Mediaeval and Modern Welsh Series, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies

- Williams, Ifor (1972), The Beginnings of Welsh Poetry: Studies, University of Wales Press, ISBN 0-7083-0035-9

Further reading

- Alcock, Leslie. Kings and Warriors, Craftsmen and Priests in Northern Britain, AD 550–850. Edinburgh, 2003.

- Alcock, Leslie. "Gwyr y Gogledd. An archaeological appraisal." Archaeologia Cambrensis 132 (1984 for 1983). pp. 1–18.

- Cessford, Craig. "Northern England and the Gododdin poem." Northern History 33 (1997). pp. 218–22.

- Clarkson, Tim. The Men of the North: the Britons of Southern Scotland. Edinburgh: John Donald, Birlinn Ltd, 2010.

- Clarkson, Tim. Strathclyde and the Anglo-Saxons in the Viking Age. Edinburgh: John Donald, Birlinn Ltd, 2014.

- Dark, Kenneth R. Civitas to Kingdom. British political continuity, 300–800. London: Leicester UP, 1994.

- Dumville, David N. "Early Welsh Poetry: Problems of Historicity." In Early Welsh Poetry: Studies in the Book of Aneirin, ed. Brynley F. Roberts. Aberystwyth, 1988. 1–16.

- Dumville, David N. "The origins of Northumbria: Some aspects of the British background." In The Origins of Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms, ed. S. Bassett. Leicester: Leicester University Press, 1989. pp. 213–22.

- Higham, N.J. "Britons in Northern England: Through a Thick Glass Darkly." Northern History 38 (2001). pp. 5–25.

- Macquarrie, A. "The Kings of Strathclyde, c.400–1018." In Medieval Scotland: Government, Lordship and Community, ed. A. Grant and K.J. Stringer. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 1993. pp. 1–19.

- Miller, Molly. "Historicity and the pedigrees of north countrymen." Bulletin of the Board of Celtic Studies 26 (1975). pp. 255–80.

- Woolf, Alex. "Cædualla Rex Brettonum and the Passing of the Old North." Northern History 41.1 (2004): 1–20.

External links

- Matthews, Keith J. "What's in a name? Britons, Angles, ethnicity and material culture from the fourth to seventh centuries." Heroic Age 4 (Winter 2001).