Kalachakra

The Kālacakra (Sanskrit: कालचक्र, romanized: kālacakra), Tibetan: དུས་ཀྱི་འཁོར་ལོ།, Wylie: dus kyi 'khor lo ; Mongolian: Цогт Цагийн Хүрдэн Tsogt Tsagiin Hurden; Chinese: 時輪) is a term used in Puranic text and in Vajrayana Buddhism that means "wheel(s) of time" (Sanskrit: kāla, lit. 'time' + Sanskrit: cakra, lit. 'wheel'). "Kālacakra(tantra)(rāja)" is the name of the foundational Buddhist tantric treatise of this tradition, composed in Sanskrit and later translated into Tibetan. The original Sanskrit texts of the Kālacakra tradition "originated during the early decades of the 11th century CE, and we know with certainty that the Śrī Kālacakra and the Vimalaprabhā commentary were completed between 1025 and ca. 1040 CE."[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Vajrayana Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

Traditions Historical traditions:

New branches:

|

|

History |

|

Pursuit |

|

Practices

Fourfold division: Twofold division: Thought forms and visualisation: Yoga:

|

|

Festivals |

|

Tantric texts |

|

Ordination and transmission |

"Kālacakra" is one of many tantric teachings and esoteric practices in Indian Buddhism and Tibetan Buddhism.[2] The tradition's origins are in India and its most active later history and presence has been in the monasteries of Tibet.[2] The tradition combines myth and history, whereby actual historical events become an allegory for the spiritual drama within a person, drawing symbolic or allegorical lessons for inner transformation towards realizing Buddha-nature.[2][3] The most important texts of this tradition include the Kālacakratantra and the expository commentary on it called Vimalaprabhā. The tradition is a form of nondualism, and devotees of the tradition believe that the Kalacakra was taught by Gautama Buddha himself.[4][5] It is today an active Vajrayana tradition, and has been offered to large public audiences.

Sources

Sanskrit originals

The Sanskrit text of the Kālacakratantra was first published by Raghu Vira and Lokesh Chandra in 1966, with a Mongolian text in volume 2.[6] This 1966 edition was based on manuscripts from the British Library and the Bir Library, Kathmandu. A critical edition of the original Sanskrit text of the Kālacakratantra was published by Biswanath Banerjee in 1985 based on manuscripts from Cambridge, London and Patna.[7][8] A further planned volume by Banerjee containing the Vimalaprabhā appears not to have been published. The Sanskrit texts of the Kālacakratantra and the Vimalaprabhā commentary were published on the basis of newly-discovered manuscripts from Nepal (5) and India (1) by Jagannatha Upadhyaya (with Vrajavallabh Dwivedi and S. S. Bahulkar, 3 vols., 1986-1994).[9] In 2010, Lokesh Chandra published a facsimile of one of the manuscripts that was used by Jagannatha Upadhyaya et al. in their edition.[10]

Tibetan translations

The Tibetan translation of the commentary Vimalaprabhā is usually studied from the 1733 Derge Kangyur edition of the Tibetan canon, vol. 40, text no. 1347. This was published by Dharma Publishing, Berkeley, USA, in 1981.[11]

David Reigle noted, in a discussion in the INDOLOGY forum of 11 April 2020, that, "the Tibetan translation of the Kālacakra-tantra made by Somanātha and 'Bro lotsawa as revised by Shong ston is found in the Lithang, Narthang, Der-ge, Co-ne, Urga, and Lhasa blockprint recensions of the Kangyur, and also in a recension with annotations by Bu ston. This Shong revision was then further revised by the two Jonang translators Blo gros rgyal mtshan and Blo gros dpal bzang po. The Jonang revision is found in the Yunglo and Peking blockprint recensions of the Kangyur, and also in a recension with annotations by Phyogs las rnam rgyal."[12]

![]()

Kālacakra tradition

Kālacakra refers both to a patron Tantric deity or yidam (Wylie: yi dam ) of Vajrayana Buddhism and to the philosophies and meditation practices contained within the Kālacakra Tantra and its many commentaries. The Kālacakra Tantra is more properly called the Kālacakra Laghutantra, and is said to be an abridged form of an original text, the Kālacakra Mūlatantra which is no longer extant. Some Buddhist masters assert that Kālacakra is the most advanced form of Vajrayana practice; it certainly is one of the most complex systems within tantric Buddhism.

The Kālacakra tradition revolves around the concept of time (kāla) and cycles (chakra): from the cycles of the planets,[13] to the cycles of human breathing, it teaches the practice of working with the most subtle energies within one's body on the path to enlightenment.

The Kālacakra deity represents a buddhahood and thus omniscience. Since Kālacakra is time and everything is the flow of time, Kālacakra knows all. Kālacakri, his spiritual consort and complement, is aware of everything that is timeless, not time-bound or out of the realm of time. In Yab-Yum, they are temporality and atemporality conjoined. Similarly, the wheel is without beginning or end. The term "wheel" evoked herewith is a principal polyvalent sign, teaching tool, organising metaphor and iconographic device within Indian religions. Some "wheel" cognates are the aṣṭamaṅgala symbol of the dharmacakra, Vishnu's Sudarshana Chakra and the theory of saṃsāra.

Kālacakra refers to many different traditions: for example, it is related to Hindu Shaiva, Samkhya, Vaishnava, Vedic, Upanishadic and Puranic traditions and also to Jainism. The Kālacakra mandala includes deities which are equally accepted by Hindus, Jains and Buddhists.[14]

The Kālacakra deity resides in the center of the mandala in his palace consisting of four mandalas, one within the other: the mandalas of body, speech, and mind, and in the very center, wisdom and great bliss.[15] The Kālacakra sand mandala is dedicated to both individual and world peace and physical balance. The Dalai Lama explains, "It is a way of planting a seed, and the seed will have karmic effect. One doesn’t need to be present at the Kalachakra ceremony in order to receive its benefits."

Kalachakra Tantra

The Kālacakra Tantra is a key text of the Kalacakra tradition.[16] It is divided into five chapters.[17]

Ground Kālacakra

The first two chapters are considered the "ground Kālacakra." The first chapter deals with what is called the "outer Kālacakra"—the physical world–and in particular the calculation system for the Kālacakra calendar, the birth and death of universes, our solar system and the workings of the elements.

The second chapter deals with the "inner Kālacakra," and concerns processes of human gestation and birth, the classification of the functions within the human body and experience, and the vajra-kaya; the expression of human physical existence in terms of channels, winds, drops and so forth. Human experience is by some described in terms of four mind states: waking, dream, deep sleep, and a fourth state which is available through the energies of sexual orgasm. The potentials (drops) which give rise to these states are described, together with the processes that flow from them.

Path and fruition

The last three chapters describe the "other" or "alternative Kālacakra," and deal with the path and fruition. The third chapter deals with the preparation for the meditation practices of the system: the initiations of Kālacakra. The fourth chapter explains the actual meditation practices themselves, both the meditation on the mandala and its deities in the generation stage practices, and the perfection or completion stage practices of the Six Yogas of Kalacakra. The fifth and final chapter describes the state of enlightenment (Relijin) that results from the practice.

Prophecy

Holy war

The Kālacakra Tantra contains passages that refer to Islam, in which Muslims are called mleccha (barbarians). It contains the prophecy of a holy war between Buddhists (led by the twenty fifth warrior-king Chakravartin Kalki) and the barbarians.[18][19][20] According to John Newman, the Buddhists who composed the Kalacakra Tantra likely borrowed the Hindu concept of Kalki and adapted the concept. They combined their idea of Shambhala with Kalki to reflect the theo-political situation they faced after the arrival of Islam in Central Asia and western Tibet.[21][22] The text prophecies a war fought by an army of Buddhists and the destruction of the Muslim persecutors of dhamma; then after the victory of good over evil and attainment of religious freedoms, Kalki ushers in a new era.[23][24][25]

One of the most important Buddhist commentaries on Kalachakra Tantra, named Vimalaprabhā and dated to the 11th-century, provides further details of this holy war.[26] The Vimalaprabhā mentions an event in the year "403" in Tibetan number symbols stating it to be the "year of the lord of the barbarians".[27] This combined by the text's statement that "Muhammad is the incarnation of al-Rahman" and the teacher of the barbarian dharma, states Newman, suggests that the 403 year must be in the era of Hijra, or equal 1012-1013 CE.[1] The many Tibetan translations of the Kalacakratantra and the commentaries therein, according to Alexander Berzin, mention practices such as the barbarians slaughtering cattle while reciting the name of its god, the veiling of women, circumcision, and five daily prayers facing their holy land, all of which leaves little doubt that the prophecy part of the text is referring to Islam.[28] Further, this supports the dating of this Kalachakra tradition text to the 11th century by Tibetan and Western scholars, and linking it to the history of Buddhism of that period.[27] The Kalachakra was introduced into Tibet in 1027 CE according to Tibetan records and per the rabjung calculations of the Tibetan astronomical calendrical calculations.[29][30]

In the year 2424, the prophecy foretells another, final holy war, the War of Shambhala, where Rudra Chakrin, the last of the Kings of Shambhala, defeats the hordes of the barbarians once and for all and erects the eternal holy land of Shambhala.[31][32]

Symbolic inner war

Another interpretation of Kālacakra's prophecy is that it refers to internal war against mental and emotional aggression. Fifteenth century Gelug commentor Khedrub Je interprets "holy war" symbolically, teaching that it mainly refers to the inner battle of the religious practitioner against barbarian tendencies.

Cosmology and calendar

The phrase "as it is outside, so it is within the body" is often found in the Kālacakra tantra to emphasize the similarities and correspondence between human beings and the cosmos.

In Tibet, the Kālacakra text is the basis of Tibetan astrological calendars.[33] It is luni-solar system and employs complicated astronomical calculations to determine, for example, the exact location of the planets. The text also is the basis of some Tibetan astrology manuals.

History and origin

Original Teaching in India and Later Teachings in Kingdom of Shambhala

According to the Ka-tan system of time calculation in the Kalachakra tradition, Buddha is believed to have died about 833 BCE.[34]

According to the Kālacakratantra, the Buddha taught the first Kālachakra root tantra in Dharanikota (near modern Amaravathi) in 5th century B.C. of southeastern India, supposedly bilocating (appearing in two places at once) at the same time as he was also delivering the Prajñāpāramitā sutras at Griddhraj Parvat in Bihar. Along with King Suchandra, ninety-six minor kings and emissaries from Shambhala were also said to have received the teachings. The Kālacakra thus passed directly to Shambhala, where it was held exclusively for hundreds of years. Later Kings of Shambhala, Mañjushrīkīrti and Pundarika, are said to have condensed and simplified the teachings into the Śri Kālacakra or Laghutantra and its main commentary, the Vimalaprabha, which remain extant today as the heart of the Kālacakra literature. Fragments of the original tantra have survived; the most significant fragment, the Sekkodesha, was commented upon by Naropa.

Mañjuśrīkīrti (Tibetan: འཇམ་དཔལ་གྲགས་པ, Wylie: 'jam dpal grags pa, THL: Jambé Drakpa ) is said to have been born in 159 BCE and ruled over Shambhala and 100,000 cities. In his domain lived 300,510 Lalo Mutegpa (Mleccha, Yavana) with heretical beliefs in Nimai sinta (sun). He expelled all these heretics from his dominions but they accepted the piṭakas (Buddhist texts) and pleaded that they be allowed to return. He accepted their petitions and taught them the Kālacakra teachings. In 59 BCE he abdicated his throne to his son, Puṇḍārika, and died soon afterwards, entering the saṃbhogakāya of Buddhahood.[35]

Chilupa/Kālacakrapada

There are currently two main traditions of Kālacakra, the Ra lineage (Wylie: rva lugs ) and the Dro lineage (Wylie: bro lugs ). Although there were many translations of the Kālacakra texts from Sanskrit into Tibetan, the Ra and Dro translations are considered to be the most reliable (more about the two lineages below). The two lineages offer slightly differing accounts of how the Kālacakra teachings returned to India from Shambhala.

In both traditions, the Kālacakra and its related commentaries (sometimes referred to as the Bodhisattvas Corpus) were returned to India in 966CE by an Indian pandit. In the Ra tradition this figure is known as Chilupa, and in the Dro tradition as Kālacakrapada the Greater. Scholars such as Helmut Hoffman have suggested they are the same person. The first masters of the tradition disguised themselves with pseudonyms, so the Indian oral traditions recorded by the Tibetans contain a mass of contradictions.

Chilupa/Kālacakrapada is said to have set out to receive the Kālacakra teachings in Shambhala, along the journey to which he encountered the Kulika (Shambhala) king Durjaya manifesting as Mañjuśrī, who conferred the Kālacakra initiation on him, based on his pure motivation.

Upon returning to India, Chilupa/Kālacakrapada is said to have defeated in debate Nadapada (Tib. Naropa), abbot of Nalanda, a great center of Buddhist thought at that time. Chilupa/Kālacakrapada then initiated Nadapada (who became known as Kālacakrapada the Lesser) into the Kālacakra, and the tradition thereafter in India and Tibet stems from these two. Nadapada established the teachings as legitimate in the eyes of the Nalanda community, and initiated into the Kālacakra such masters as Atiśa (who, in turn, initiated the Kālacakra master Pindo Acharya (Tib. Pitopa)).

A Tibetan history, the Dpag bsam ljon bzang, as well as architectural evidence, indicates that the Ratnagiri, Odisha mahavihara was an important center for the dissemination of the Kālacakratantra in India.

The Kālacakra tradition, along with all Buddhism, vanished from India in the wake of the Muslim invasions, surviving only in Nepal.

Spread to Tibet

According to Tāranātha, seventeen distinct lineages of Kālacakra[36] that came from India to Tibet were recorded and compiled by the Jonang master, Kunpang Chenpo. The main two lineages of these that are practised today are the Dro lineage and the Ra lineage. The Dro lineage was established in Tibet by a Kashmiri disciple of Nalandapa named Pandita Somanatha, who traveled to Tibet in 1027 (or 1064CE, depending on the calendar used), and his translator Dro' Lotsawa Shérap Drak Wylie: bro lo tsa ba shes rab grags , from which it takes its name. The Ra lineage was brought to Tibet by another Kashmiri disciple of Nadapada named Samantashri, and translated by Ra Lotsawa Chörap Wylie: rwa lo tsa ba chos rab .

The Ra lineage became particularly important in the Sakya school of Tibetan Buddhism, where it was held by such prominent masters as Sakya Pandita (1182–1251), Drogön Chögyal Phagpa (1235–1280), Butön Rinchen Drup (1290–1364), and Dölpopa Shérap Gyeltsen (1292–1361). The latter two, both of whom also held the Dro lineage, are particularly well known expositors of the Kālacakra in Tibet, the practice of which is said to have greatly informed Dölpopa's exposition of shentong. A strong emphasis on Kālacakra practice and exposition of the zhentong view were the principal distinguishing characteristics of the Jonang school that traces its roots to Dölpopa Shérap Gyeltsen.

The teaching of the Kālacakra was further advanced by the great Jonang scholar Taranatha (1575–1634). In the 17th century, the government of the 5th Dalai Lama outlawed the Jonang school, closing down or forcibly converting most of its monasteries. The writings of Dolpopa Sherab Gyaltsen, Taranatha, and other prominent zhentong scholars were banned. Ironically, it was also at this time that the Gelug school absorbed much of the Jonang Kālacakra tradition.

Today, Kālacakra is practiced by all schools of Tibetan Buddhism, although it appears most prominently in the Gelug lineage. It is the main tantric practice for the Jonangpa, whose school persists to this day with a small number of monasteries in Kham, Qinghai and Sichuan. Efforts are under way to have the Jonang tradition be recognized officially as a fifth tradition of Tibetan Buddhism.

Practice

Initiation

As in all Vajryana practices, the Kālacakra initiations empower the disciple to practice the Kālacakra tantra in the service of attaining Buddhahood. There are two main sets of initiations in Kālacakra, eleven in all. The first of these two sets concerns preparation for the generation stage meditations of Kālacakra. The second concerns preparation for the completion stage meditations known as the Six Yogas of Kālacakra. Attendees who don't intend to carry out the practice are often only given the lower seven initiations.

The Kālacakra sand Mandala is dedicated to both individual and world peace and physical balance. The Dalai Lama explains: "It is a way of planting a seed, and the seed will have karmic effect. One doesn't need to be present at the Kālacakra ceremony in order to receive its benefits."

Kālacakra practice today in the Tibetan Buddhist schools

Butön Rinchen Drup had considerable influence on the later development of the Gelug and Sakya traditions of Kālacakra and Dölpopa and Taranatha on the development of the Jonang tradition on which the Kagyu, Nyingma, and the Tsarpa branch of the Sakya draw. The Jonang tradition mainly use the texts of Jonang masters Bamda Gelek Gyatso[37] and Tāranātha[38] to teach Kālacakra practice in Tibet and exile. The Nyingma and Kagyu rely heavily on the extensive, Jonang-influenced Kālacakra commentaries of Jamgon Ju Mipham Gyatso and Jamgon Kongtrul, both of whom took a strong interest in the tradition. The Tsarpa branch of the Sakya maintain the practice lineage for the six branch yoga of Kālacakra in the Jonang tradition.

There were many other influences and much cross-fertilization between the different traditions, and indeed the Dalai Lama asserted that it is acceptable for those initiated in one Kālacakra tradition to practice in others.

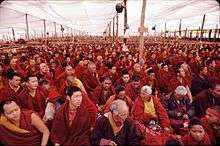

Gelugpa

The Dalai Lamas have had specific interest in the Kālacakra practice, particularly the First, Second, Seventh, Eighth, and the current (Fourteenth) Dalai Lamas. The present Dalai Lama has given over thirty Kālacakra initiations all over the world, and is the most prominent Kālacakra lineage holder alive today. Billed as the "Kālacakra for World Peace," they draw tens of thousands of people. Generally, it is unusual for tantric initiations to be given to large public assemblages, but the Kālacakra has always been an exception.

The Dalai Lama, Kalu Rinpoche, and others have stated that the public exposition of this tantra is necessary in the current degenerate age. The initiation may be received simply as a blessing for the majority of those attending, however, many of the more qualified attendees do take the commitments and subsequently engage in the practice.

Kālacakra Initiations given by XIV Dalai Lama.[39]

- 1. Norbu Lingka, Lhasa, Tibet, in May 1954

- 2. Norbu Lingka, Lhasa, Tibet, in April 1956

- 3. Dharamsala, India, in March 1970

- 4. Bylakuppe, South India, in May 1971

- 5. Bodh Gaya, India, in January 1974

- 6. Leh, Ladakh, India, in September 1976

- 7. Deer Park Buddhist Center, Madison, Wisconsin, USA, in July 1981

- 8. Dirang, Arunachal Pradesh, India, in April 1983

- 9. Lahaul & Spiti, India, in August 1983

- 10. Rikon, Switzerland, in July 1985

- 11. Bodh Gaya, India, in December 1985

- 12. Zanskar, Ladakh, India, in July 1988

- 13. Los Angeles, USA, in July 1989

- 14. Sarnath, India, in December 1990

- 15. New York, USA, in October 1991

- 16. Kalpa, Himachal Pradesh, India, in August 1992

- 17. Gangtok, Sikkim, India, in April 1993

- 18. Jispa, HP, India, in August 1994

- 19. Barcelona, Spain, in December 1994

- 20. Mundgod, South India, in January 1995

- 21. Ulanbaator, Mongolia, in August 1995

- 22. Tabo, HP, India, in June 1996

- 23. Sydney, Australia, in September 1996

- 24. Salugara, West Bengal, India, in December 1996.

- 25. Bloomington, Indiana, USA, in August 1999.

- 26. Key Monastery, Spiti, Himachal Pradesh, India, in August 2000.[40]

- 27. Graz, Austria, in October 2002.

- 28. Bodh Gaya, Bihar, India, in January 2003.

- 29. Toronto, Canada, in April 2004.

- 30. Amaravathi, India in January 2006.

- 31. Washington, DC, USA, in July 2011.

- 32. Bodh Gaya, India, in January 2012.

- 33. Leh Ladakh, India July 2014

- 34. Bodh Gaya, Bihar, India, in January 2017.

The 33rd Kalachakra ceremony was held in Leh, Ladakh, India from July 3 to July 12, 2014. About 150,000 devotees and 350,000 tourists were expected to participate in the festival.[41]

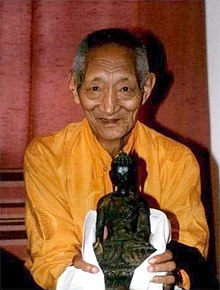

Kirti Tsenshab Rinpoche (1926–2006), the 9th Jebtsundamba Khutughtu, Jhado Rinpoche and the late Gen Lamrimpa (d. 2003) were also among prominent Gelugpa Kālacakra masters.

Kagyu

The Kālacakra tradition practiced in the Karma Kagyu and Shangpa Kagyu schools is derived from the Jonang tradition and was largely systematized by Jamgon Kongtrul, who wrote the text that is now used for empowerment. The 2nd and 3rd Jamgon Kongtrul (1954–1992) were also prominent Kālacakra lineage holders, with the 3rd Jamgon Kongtrul giving the initiation publicly in North America on at least one occasion (Toronto 1990).[42]

The chief Kālacakra lineage holder for the Kagyu lineage was Kalu Rinpoche (1905–1990), who gave the initiation several times in Tibet, India, Europe and North America (e.g., New York 1982[43]). Upon his death, this mantle was assumed by his heart son, Bokar Tulku Rinpoche (1940–2004), who in turn passed it on to Khenpo Lodro Donyo Rinpoche. Bokar Monastery, of which Donyo Rinpoche is now the head, features a Kālacakra stupa and is a prominent retreat center for Kālacakra practice in the Kagyu lineage.

Tenga Rinpoche was also a prominent Kagyu holder of the Kālacakra; he gave the initiation in Grabnik, Poland in August, 2005.

Lopon Tsechu performed Kālacakra initiations and build Kālacakra stupa in Karma Guen buddhist center in southern Spain. Another prominent Kālacakra master is the Second Beru Khyentse.

Chögyam Trungpa, while not a noted Kālacakra master, became increasingly involved later in his life with what he termed Shambhala teachings, derived in part from the Kālacakra tradition, in particular, the mind terma which he received from the Kalki.

Nyingma

Among the prominent recent and contemporary Nyingma Kālacakra masters are Dzongsar Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö (1894–1959), Dilgo Khyentse (1910–1991), and Penor Rinpoche (1932–2009).

Sakya

Sakya Trizin, the present head of the Sakya lineage, has given the Kālacakra initiation many times and is a recognized master of the practice.

The Sakya master H.E. Chogye Trichen Rinpoche is one of the main holders of the Kālacakra teachings. Chogye Rinpoche is the head of the Tsharpa School, one of the three main schools of the Sakya tradition of Tibetan Buddhism.

One of the previous Chogye Trichen Rinpoches, Khyenrab Choje (1436–97), beheld the sustained vision of the female tantric deity Vajrayogini at Drak Yewa in central Tibet, and received extensive teachings and initiations directly from her. Two forms of Vajrayogini appeared out of the face of the rocks at Drak Yewa, one red in color and the other white, and they bestowed the Kālacakra initiation on Khyenrab Choje. When he asked if there was any proof of this, his attendant showed the master the kusha grass that Khyenrab Choje brought back with him from the initiation. It was unlike any kusha grass found in this world, with rainbow lights sparkling up and down the length of the dried blades of grass. This direct lineage from Vajrayogini is the 'shortest', the most recent and direct, lineage of the Kālacakra empowerment and teachings that exists in this world. In addition to being known as the emanation of Manjushri, Khyenrab Choje had previously been born as many of the Kings of Shambhala as well as numerous Buddhist masters of India. These are some indications of his unique relationship to the Kālacakra tradition.

Chogye Trichen Rinpoche is the holder of six different Kālacakra initiations, four of which, the Bulug, Jonang, Maitri-gyatsha, and Domjung, are contained within the Gyude Kuntu, the Collection of Tantras compiled by Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo and his disciple Loter Wangpo. Rinpoche has offered all six of these empowerments to Sakya Trizin, the head of the Sakya School of Tibetan Buddhism.

Rinpoche has given the Kālacakra initiation in Tibet, Mustang, Kathmandu, Malaysia, the United States, Taiwan, and Spain, and is widely regarded as a definitive authority on Kālacakra. In 1988 he traveled to the United States, giving the initiation and complete instructions in the practice of the six-branch Vajrayoga of Kālacakra according to the Jonangpa tradition in Boston.

Chogye Rinpoche has completed extensive retreat in the practice of Kālacakra, particularly of the six-branch yoga (sadangayoga) in the tradition of the Jonangpa school according to Jetsun Taranatha. In this way, Chogye Rinpoche has carried on the tradition of his predecessor Khyenrab Choje, the incarnation of the Shambhala kings who received the Kālacakra initiation from Vajrayogini herself. When Chogye Rinpoche was young, one of his teachers dreamed that Rinpoche was the son of the King of Shambhala, the pure land that upholds the tradition of Kālacakra. (See biography of Chogye Trichen Rinpoche in "Parting from the Four Attachments", Snow Lion Publications, 2003.)

Jonang

Once deemed heretical by the 5th Dalai Lama and successors, and even thought to be extinct, the Jonang tradition has in fact survived and is now officially recognized by the Tibetan Government in exile as a fifth school of Tibetan Buddhism. Jonang is particularly important in that it has preserved the Kālacakra practice lineage, especially of the completion stage practices. In fact, the Kālacakra is the main tantric practice in the Jonang tradition. Khenpo Kunga Sherab Rinpoche[44] is one contemporary Jonangpa master of Kālacakra. Khentrul Rinpoche[45] who is based in Australia is another Kalachakra teacher who is travelling the world giving teachings and empowerments.

Iconography

Tantric iconography including sharp weapons, shields, and corpses similarly appears in conflict with those tenets of non-violence but instead represent the transmutation of aggression into a method for overcoming illusion and ego. Both Kālacakra and his dharmapala protector Vajravega hold a sword and shield in their paired second right and left hands. This is an expression of the Buddha's triumph over the attack of Mara and his protection of all sentient beings.[46] Symbolism researcher Robert Beer writes the following about tantric iconography of weapons and mentions the charnel ground:

Many of these weapons and implements have their origins in the wrathful arena of the battlefield and the funereal realm of the charnel grounds. As primal images of destruction, slaughter, sacrifice, and necromancy these weapons were wrested from the hands of the evil and turned - as symbols - against the ultimate root of evil, the self-cherishing conceptual identity that gives rise to the five poisons of ignorance, desire, hatred, pride, and jealousy. In the hands of siddhas, dakinis, wrathful and semi-wrathful yidam deities, protective deities or dharmapalas these implements became pure symbols, weapons of transformation, and an expression of the deities' wrathful compassion which mercilessly destroys the manifold illusions of the inflated human ego.[47]

See also

References

- NEWMAN, JOHN (1998). "The Epoch of the Kālacakra Tantra". Indo-Iranian Journal. 41 (4): 319–349. doi:10.1163/000000098124992781. ISSN 0019-7246. JSTOR 24663342.

- John Newman (1991). Geshe Lhundub Sopa (ed.). The Wheel of Time: Kalachakra in Context. Shambhala. pp. 51–54, 62–77. ISBN 978-1-55939-779-7.

- Dalai Lama (2016). Jeffrey Hopkins (ed.). Kalachakra Tantra: Rite of Initiation. Wisdom Publications. pp. 13–17. ISBN 978-0-86171-886-3.

- Dakpo Tashi Namgyal (2014). Mahamudra: The Moonlight: Quintessence of Mind and Meditation. Simon and Schuster. pp. 444 note 17. ISBN 978-0-86171-950-1.

- Fabrice Midal (2005). Recalling Chogyam Trungpa. Shambhala Publications. pp. 457–458. ISBN 978-0-8348-2162-0.

- Raghu Vira; Lokesh Chandra (1966). Kalacakra-tantra and other texts. New Delhi: International Academy of Indian Culture. OCLC 976951786.

- Banerjee, Biswanath (1985). A critical Edition of Srī Kālacakratantra-Rāja (coll. with the Tibetan version). Calcutta: The Asiatic Society. OCLC 1071172364.

- Banerjee, Biswanath (1993). A critical edition of Śri Kālacakratantra-Rāja: (collated with the Tibetan version). Calcutta: The Asiatic Society. OCLC 258523649.

- Tarun Dwivedi(S/o Later Vraj Vallabh Dwivedi). Vimalprabha Tika Of Kalkin Shri Pundarika On Shri Laghu Kala Chakra Tantraraja By Shri Manju Shri Yashas Ed. Vraj Vallabha Dwivedi And Bahulkar Vol 1.

- Sanskrit manuscripts from Tibet : Vimalaprabhā commentary on the Kālacakra-tantra, Pañcarakṣā. Lokesh Chandra., International Academy of Indian Culture. New Delhi: International Academy of Indian Culture and Aditya Prakashan. 2010. ISBN 978-81-7742-094-4. OCLC 605026692.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Tarthang, Tulku (1981). The Nyingma Edition of the sDe-dge bKa'-'gyur and bsTan-'gyur. Berkeley, CA: Dharama Publishing. OCLC 611093555.

- Reigle, David (2020-04-11). "INDOLOGY post". INDOLOGY archive.

- 14th Dalai Lama (1985). Hopkins, Jeffrey (ed.). Kālachakra Tantra: Rite of Initiation for the Stage of Generation: a Commentary on the Text of Kay-drup-ge-lek-bēl-sang-bō (2 ed.). London: Wisdom Publications. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-86171-028-7.

The external Kālacakra refers to all of the environment - the mountains, fences, homes, planets, constellations of stars, solar systems, and so forth.

- Kalachakra History //archived 16 Sep 2014

- "Tibetan Buddhism - Kalachakra Tantra". Thewildrose.net. Retrieved 2014-06-02.

- Khedrup Norsang Gyatso (2016). Ornament of Stainless Light: An Exposition of the Kalachakra Tantra. Wisdom Publications. pp. i–xiv. ISBN 978-0-86171-742-2.

- Kilty, G Ornament of Stainless Light, Wisdom 2004, ISBN 0-86171-452-0

- Yijiu JIN (2017). Islam. BRILL Academic. pp. 49–52. ISBN 978-90-474-2800-8.

- Martin Riesebrodt (2010). The Promise of Salvation: A Theory of Religion. University of Chicago Press. pp. 167–168. ISBN 978-0-226-71394-6.

- Donald S. Lopez Jr. (2015). Buddhism in Practice. Princeton University Press. pp. 203–204. ISBN 978-1-4008-8007-2.

- John Newman (2015). Donald S. Lopez Jr. (ed.). Buddhism in Practice (Abridged ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 203.

- Sopa, Lhundub. The Wheel of Time: Kalachakra in Context. Sambhala. pp. 83–84 with note 4.

- Yijiu JIN (2017). Islam. BRILL Academic. pp. 49–52. ISBN 978-90-474-2800-8.

- [a] Björn Dahla (2006). Exercising Power: The Role of Religions in Concord and Conflict. Donner Institute for Research in Religious and Cultural History. pp. 90–91. ISBN 978-952-12-1811-8., Quote: "(...) the Shambala-bodhisattva-king [Cakravartin Kalkin] and his army will defeat and destroy the enemy army, the barbarian Muslim army and their religion, in a kind of Buddhist Armadgeddon. Thereafter Buddhism will prevail.";

[b] David Burton (2017). Buddhism: A Contemporary Philosophical Investigation. Taylor & Francis. p. 193. ISBN 978-1-351-83859-7.

[c] Johan Elverskog (2011). Anna Akasoy; et al. (eds.). Islam and Tibet: Interactions Along the Musk Routes. Ashgate Publishing. pp. 293–310. ISBN 978-0-7546-6956-2. - John Newman (2015). Donald S. Lopez Jr. (ed.). Buddhism in Practice (Abridged ed.). Princeton University Press. pp. 202–205.;

Jan Nattier (1991). Once Upon a Future Time: Studies in a Buddhist Prophecy of Decline. Jain Publishing. pp. 59–61 with footnotes. ISBN 978-0-89581-926-0. - John Newman (1985). Geshe Lhundub Sopa (ed.). The Wheel of Time: Kalachakra in Context. Sambhala. pp. 56–78, 83–86 with notes.

- John Newman (1985). Geshe Lhundub Sopa; et al. (eds.). The Wheel of Time: The Kalachakra in Context. Shambhala. pp. 56–79, 85–87 with notes. ISBN 978-15593-97-797.

- Alexander Berzin (2007). Perry Schmidt-Leukel (ed.). Islam and Inter-faith Relations: The Gerald Weisfeld Lectures 2006. SCM Press. pp. 230–238, context: 225–247.

- Yijiu JIN (2017). Islam. BRILL Academic. p. 51. ISBN 978-90-474-2800-8.

- Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal (2008). Light of Fearless Indestructible Wisdom: The Life and Legacy of His Holiness Dudjom Rinpoche. Shambhala. pp. 248–249. ISBN 978-1-55939-839-8.

- Victor and Victoria Trimondi (2002). Hitler, Buddha, Krishna - an Unholy Alliance. Wirtschaftsverlag Ueberreuter. ISBN 978-3800038879.

- "War of Shambhala - Chinese Buddhist Encyclopedia". chinabuddhismencyclopedia.com.

- Tibetan Astrology by Philippe Cornu, Shambala 1997, ISBN 1-57062-217-5

- Das, Sarat Chandra (1882). Contributions on the Religion and History of Tibet. First published in: Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Vol. LI. Reprint: Manjushri Publishing House, Delhi. 1970, pp. 81-82 footnote 6.

- Das, Sarat Chandra (1882). Contributions on the Religion and History of Tibet. First published in: Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Vol. LI. Reprint: Manjushri Publishing House, Delhi. 1970, pp. 81-82;

- see https://www.shentongkalacakra.com/kalacakra-2/the-seventeen-lineages-of-the-six-vajra-yogas-by-jetsun-taranatha/

- Tomlin, Adele; Gyatso, Bamda Gelek (April 2019). The Chariot that Transports to the Four Kayas. Library Tibetan Works and Archives.

- One Hundred Blazing Lights ('od rgyan bar ba) and Meaningful to See (mthong ba don ldan)

- Lama, The 14th Dalai (January 6, 2020). "Introduction to the Kalachakra". The 14th Dalai Lama.

- "Official Website of Lahaul-Spiti District Administration". Deputy Commissioner, Lahaul and Spiti. Archived from the original on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

- "Tibetans head to Leh to participate in 34rd [sic] kalachakra Initiations". IANS. news.biharprabha.com. 2 July 2014. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

- "Kālacakra History". International Kalachakra Network. Archived from the original on 2014-03-27. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- "Dorje Chang Kalu Rinpoche". The Lion's Roar. Simhanada. Archived from the original on 2007-10-24. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- "Jonang Foundation". Jonang Foundation. Archived from the original on January 3, 2008.

- "Khentrul Rinpche". Khentrul Rinpoche.

- Beer, Robert (2004) The Encyclopedia of Tibetan Symbols and Motifs ISBN 1-932476-10-5 p. 298

- Beer, Robert (2004) The Encyclopedia of Tibetan Symbols and Motifs ISBN 1-932476-10-5 p. 233

Sources

- ed, by Edward A. Arnold on behalf of Namgyal Monastery Institute of Buddhist Studies, fore. by Robert A. F. Thurman. As Long As Space Endures: Essays on the Kalacakra Tantra in Honor of the Dalai Lama Snow Lion Publications, 2009.

- Berzin, A. Taking the Kalachakra Initiation, Snow Lion Publications, 1997, ISBN 1-55939-084-0 (available in German, French, Italian, Russian)

- Brauen, M. Das Mandala, Dumont, ISBN 3-7701-2509-6 (also available in English, Italian, Dutch and other languages)

- Bryant, B. The Wheel of Time Sand Mandala, Snow Lion Publications, 1995

- Dalai Lama, Hopkins J. The Kalachakra Tantra, Rite of Initiation Wisdom, 1985

- Dhargyey, N. et al. Kalachakra Tantra Motilal Barnassidas

- Henning, Edward (2007). Kalacakra and the Tibetan Calendar. Treasury of the Buddhist Sciences. NY: Columbia University Press. p. 408. ISBN 978-0-9753734-9-1.

- Khedrup Norsang Gyatso; Kilty, Gavin (translator) (2004). Jinpa, Thupten (ed.). Ornament of Stainless Light: An Exposition of the Kālacakra Tantra. The Library of Tibetan Classics. Wisdom Publications. p. 736. ISBN 0-86171-452-0.

- Gen Lamrimpa and B. Allan Wallace Transcending Time, an Explanation of the Kalachakra Six-Session Guru Yoga (Wisdom 1999)

- Haas, Ernst and Minke, Gisela. (1976). "The Kālacakra Initiation." The Tibet Journal. Vol. 1, Nos. 3 & 4. Autumn 1976, pp. 29–31.

- Mullin, G.H. The Practice of Kalachakra Snow Lion Publications, 1991

- Namgyal Monastery Kalachakra, Tibet Domani 1999

- Newman, J.R. The Outer Wheel of Time: Vajrayana Buddhist cosmology in the Kalacakra tantra, a dissertation 1987, dissertation. UMI number 8723348.

- Reigle, D. Kalacakra Sadhana and Social ResponsibilitySpirit of the Sun Publications 1996

- Tomlin, A The Chariot that Transports to the Four Kayas: Stages of Meditation on the Glorious Kalacakra by Bamda Gelek Gyatso. Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, 2019.

- Wallace, V.A. The Inner Kalacakratantra: A Buddhist Tantric View of the Individual Oxford University Press, 2001

- Wallace, Thurman, Yarnall Kalacakratantra: The Chapter On The Individual Together With The Vimalaprabha American Institute of Buddhist Studies, 2004

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kalachakra. |

- A Resource Guide to the works in English on the Kalachakra

- Kalachakra Mandala

- Kalacakra.org

- Kalachakra For World Peace Graz 2002

- Toronto 2004

- Extensive Kālacakra section by Alexander Berzin on Study Buddhism

- International Kalachakra Network

- The Jonang Foundation

- Critical Forum Kalachakra

- www.shentongkalacakra.com