Time management

Time management is the process of planning and exercising conscious control of time spent on specific activities, especially to increase effectiveness, efficiency, and productivity. It involves a juggling act of various demands upon a person relating to work, social life, family, hobbies, personal interests and commitments with the finiteness of time. Using time effectively gives the person "choice" on spending/managing activities at their own time and expediency.[1] Time management may be aided by a range of skills, tools, and techniques used to manage time when accomplishing specific tasks, projects, and goals complying with a due date. Initially, time management referred to just business or work activities, but eventually the term broadened to include personal activities as well. A time management system is a designed combination of processes, tools, techniques, and methods. Time management is usually a necessity in any project development as it determines the project completion time and scope. It is also important to understand that both technical and structural differences in time management exist due to variations in cultural concepts of time.

The major themes arising from the literature on time management include the following:

- Creating an environment conducive to effectiveness (In terms of: cost/benefit, quality of results and time to complete tasks/project).

- Setting of priorities

- The related process of reduction of time spent on non-priorities

- Implementation of goals

Related concepts

Time management is related to different concepts such as:

- Project management: Time management can be considered to be a project management subset and is more commonly known as project planning and project scheduling. Time management has also been identified as one of the core functions identified in project management.[2]

- Attention management relates to the management of cognitive resources, and in particular the time that humans allocate their mind (and organize the minds of their employees) to conduct some activities.

- Timeblocking is a time management strategy that specifically advocates for allocating chunks of time to dedicated tasks in order to promote deeper focus and productivity.

Organizational time management is the science of identifying, valuing and reducing time cost wastage within organizations. It identifies, reports and financially values sustainable time, wasted time and effective time within an organization and develops the business case to convert wasted time into productive time through the funding of products, services, projects or initiatives at a positive return on investment.

Cultural views of time management

Differences in the way a culture views time can affect the way their time is managed. For example, a linear time view is a way of conceiving time as flowing from one moment to the next in a linear fashion. This linear perception of time is predominant in America along with most Northern European countries such as, Germany, Switzerland, and England.[3] People in these cultures tend to place a large value on productive time management, and tend to avoid decisions or actions that would result in wasted time.[3] This linear view of time correlates to these cultures being more “monochronic”, or preferring to do only one thing at a time. Generally speaking, this cultural view leads to a better focus on accomplishing a singular task and hence, more productive time management.

Another cultural time view is multi-active time view. In multi-active cultures, most people feel that the more activities or tasks being done at once the better. This creates a sense of happiness.[3] Multi-active cultures are “polychronic” or prefer to do multiple tasks at once. This multi-active time view is prominent in most Southern European countries such as Spain, Portugal, and Italy.[3] In these cultures, the people often tend to spend time on things they deem to be more important such as placing a high importance on finishing social conversations.[3] In business environments, they often pay little attention to how long meetings last, rather the focus is on having high quality meetings. In general, the cultural focus tends to be on synergy and creativity over efficiency.[4]

A final cultural time view is a cyclical time view. In cyclical cultures, time is considered neither linear nor event related. Because days, months, years, seasons, and events happen in regular repetitive occurrences, time is viewed as cyclical. In this view, time is not seen as wasted because it will always come back later, hence, there is an unlimited amount of it.[3] This cyclical time view is prevalent throughout most countries in Asia including Japan, China, and Tibet. It is more important in cultures with cyclical concepts of time to complete tasks correctly, therefore, most people will spend more time thinking about decisions and the impact they will have before acting on their plans.[4] Most people in cyclical cultures tend to understand that other cultures have different perspectives of time and are cognizant of this when acting on a global stage.

Creating an effective environment

Some time-management literature stresses tasks related to the creation of an environment conducive to "real" effectiveness. These strategies include principles such as:

- "get organized" - the triage of paperwork and of tasks

- "protecting one's time" by insulation, isolation and delegation

- "achievement through goal-management and through goal-focus" - motivational emphasis

- "recovering from bad time-habits" - recovery from underlying psychological problems, e.g. procrastination

Also, the timing of tackling tasks is important as tasks requiring high levels of concentration and mental energy are often done at the beginning of the day when a person is more refreshed. Literature also focuses on overcoming chronic psychological issues such as procrastination.

Excessive and chronic inability to manage time effectively may result from Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or attention deficit disorder (ADD).[5] Diagnostic criteria include a sense of underachievement, difficulty getting organized, trouble getting started, trouble managing many simultaneous projects, and trouble with follow-through.[6] Daniel Amen focuses on the prefrontal cortex which is the most recently evolved part of the brain. It manages the functions of attention span, impulse managegment, organization, learning from experience and self-monitoring, among others. Some authors argue that changing the way the prefrontal cortex works is possible and offer a solution.[7]

Setting priorities and goals

Time management strategies are often associated with the recommendation to set personal goals. The literature stresses themes such as:

- "Work in Priority Order" – set goals and prioritize

- "Set gravitational goals" – that attract actions automatically

These goals are recorded and may be broken down into a project, an action plan, or a simple task list. For individual tasks or for goals, an importance rating may be established, deadlines may be set, and priorities assigned. This process results in a plan with a task list, schedule, or calendar of activities. Authors may recommend a daily, weekly, monthly or other planning periods associated with different scope of planning or review. This is done in various ways, as follows.

ABCD analysis

A technique that has been used in business management for a long time is the categorization of large data into groups. These groups are often marked A, B, and C—hence the name. Activities are ranked by these general criteria:

- A – Tasks that are perceived as being urgent and important,

- B – Tasks that are important but not urgent,

- C – Tasks that are unimportant but urgent,

- D – Tasks that are unimportant and not urgent.

Each group is then rank-ordered by priority. To further refine the prioritization, some individuals choose to then force-rank all "B" items as either "A" or "C". ABC analysis can incorporate more than three groups.[8]

ABC analysis is frequently combined with Pareto analysis.

Pareto analysis

See also: Pareto analysis

The Pareto Principle is the idea that 80% of tasks can be completed in 20% of the given time, and the remaining 20% of tasks will take up 80% of the time. This principle is used to sort tasks into two parts. According to this form of Pareto analysis it is recommended that tasks that fall into the first category be assigned a higher priority.

The 80-20-rule can also be applied to increase productivity: it is assumed that 80% of the productivity can be achieved by doing 20% of the tasks. Similarly, 80% of results can be attributed to 20% of activity.[9] If productivity is the aim of time management, then these tasks should be prioritized higher.[10]

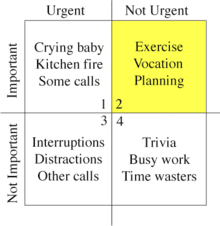

The Eisenhower Method

The "Eisenhower Method" stems from a quote attributed to Dwight D. Eisenhower: "I have two kinds of problems, the urgent and the important. The urgent are not important, and the important are never urgent."[11] Note that Eisenhower does not claim this insight for his own, but attributes it to an (unnamed) "former college president."[12]

Using the Eisenhower Decision Principle, tasks are evaluated using the criteria important/unimportant and urgent/not urgent,[13][14] and then placed in according quadrants in an Eisenhower Matrix (also known as an "Eisenhower Box" or "Eisenhower Decision Matrix"[15]). Tasks are then handled as follows:

Tasks in

- Important/Urgent quadrant are done immediately and personally[16] e.g. crises, deadlines, problems.[15]

- Important/Not Urgent quadrant get an end date and are done personally[16] e.g. relationships, planning, recreation.[15]

- Unimportant/Urgent quadrant are delegated[16] e.g. interruptions, meetings, activities.[15]

- Unimportant/Not Urgent quadrant are dropped[16] e.g. time wasters, pleasant activities, trivia.[15]

This method is inspired by the above quote from U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Note, however, that Eisenhower seems to say that things are never both important and urgent, or neither: So he has two kinds of problems, the urgent and the important.

POSEC method

POSEC is an acronym for "Prioritize by Organizing, Streamlining, Economizing and Contributing". The method dictates a template which emphasizes an average individual's immediate sense of emotional and monetary security. It suggests that by attending to one's personal responsibilities first, an individual is better positioned to shoulder collective responsibilities.[17]

Inherent in the acronym is a hierarchy of self-realization, which mirrors Abraham Maslow's hierarchy of needs:

- Prioritize – Your time and define your life by goals.

- Organize – Things you have to accomplish regularly to be successful (family and finances).

- Streamline – Things you may not like to do, but must do (work and chores).

- Economize – Things you should do or may even like to do, but they're not pressingly urgent (pastimes and socializing).

- Contribute – By paying attention to the few remaining things that make a difference (social obligations).

Elimination of non-priorities

Time management also covers how to eliminate tasks that do not provide value to the individual or organization.

According to the Wall Street Journal contributor Jared Sandberg,[18] task lists "aren't the key to productivity [that] they're cracked up to be". He reports an estimated "30% of listers spend more time managing their lists than [they do] completing what's on them".

The sofware executive Elisabeth Hendrickson asserts[19] that rigid adherence to task lists can create a "tyranny of the to-do list" that forces one to "waste time on unimportant activities".

Any form of stress is considered to be debilitative for learning and life, even if adaptability could be acquired its effects are damaging.[20] But stress is an unavoidable part of daily life and Reinhold Niebuhr suggests to face it, as if having "the serenity to accept the things one cannot change and having the courage to change the things one can."

Part of setting priorities and goals is the emotion "worry," and its function is to ignore the present to fixate on a future that never arrives, which leads to the fruitless expense of one's time and energy. It is an unnecessary cost or a false aspect that can interfere with plans due to human factors. The Eisenhower Method is a strategy used to compete worry and dull-imperative tasks.[21] Worry as stress, is a reaction to a set of environmental factors; understanding this is not a part of the person gives the person possibilities to manage them. Athletes under a coach call this management as "putting the game face."[22]

Change is hard and daily life patterns are the most deeply ingrained habits of all. To eliminate non-priorities in study time it is suggested to divide the tasks, capture the moments, review task handling method, postpone unimportant tasks (understood by its current relevancy and sense of urgency reflects wants of the person rather than importance), manage life balance (rest, sleep, leisure), and cheat leisure and nonproductive time (hearing audio taping of lectures, going through presentations of lectures when in a queue, etc.).[23]

Certain unnecessary factors that affect time management are habits, lack of task definition (lack of clarity), over-protectiveness of the work, the guilt of not meeting objectives and subsequent avoidance of present tasks, defining tasks with higher expectations than their worth (over-qualifying), focusing on matters that have an apparent positive outlook without assessing their importance to personal needs, tasks that require support and time, sectional interests and conflicts, etc.[24] A habituated systematic process becomes a device that the person can use with ownership for effective time management.

Implementation of goals

.jpg)

A task list (also called a to-do list or "things-to-do") is a list of tasks to be completed, such as chores or steps toward completing a project. It is an inventory tool which serves as an alternative or supplement to memory.

Task lists are used in self-management, business management, project management, and software development. It may involve more than one list.

When one of the items on a task list is accomplished, the task is checked or crossed off. The traditional method is to write these on a piece of paper with a pen or pencil, usually on a note pad or clip-board. Task lists can also have the form of paper or software checklists.

Writer Julie Morgenstern suggests "do's and don'ts" of time management that include:

- Map out everything that is important, by making a task list.

- Create "an oasis of time" for one to manage.

- Say "No".

- Set priorities.

- Don't drop everything.

- Don't think a critical task will get done in one's spare time.[25]

Numerous digital equivalents are now available, including personal information management (PIM) applications and most PDAs. There are also several web-based task list applications, many of which are free.

Task list organization

Task lists are often diarized and tiered. The simplest tiered system includes a general to-do list (or task-holding file) to record all the tasks the person needs to accomplish and a daily to-do list which is created each day by transferring tasks from the general to-do list. An alternative is to create a "not-to-do list", to avoid unnecessary tasks.[25]

Task lists are often prioritized:

- A daily list of things to do, numbered in the order of their importance, and done in that order one at a time until daily time allows, is attributed to consultant Ivy Lee (1877–1934) as the most profitable advice received by Charles M. Schwab (1862–1939), president of the Bethlehem Steel Corporation.[26][27][28]

- An early advocate of "ABC" prioritization was Alan Lakein, in 1973. In his system "A" items were the most important ("A-1" the most important within that group), "B" next most important, "C" least important.[8]

- A particular method of applying the ABC method[29] assigns "A" to tasks to be done within a day, "B" a week, and "C" a month.

- To prioritize a daily task list, one either records the tasks in the order of highest priority, or assigns them a number after they are listed ("1" for highest priority, "2" for second highest priority, etc.) which indicates in which order to execute the tasks. The latter method is generally faster, allowing the tasks to be recorded more quickly.[25]

- Another way of prioritizing compulsory tasks (group A) is to put the most unpleasant one first. When it's done, the rest of the list feels easier. Groups B and C can benefit from the same idea, but instead of doing the first task (which is the most unpleasant) right away, it gives motivation to do other tasks from the list to avoid the first one.

- A completely different approach which argues against prioritizing altogether was put forward by British author Mark Forster in his book "Do It Tomorrow and Other Secrets of Time Management". This is based on the idea of operating "closed" to-do lists, instead of the traditional "open" to-do list. He argues that the traditional never-ending to-do lists virtually guarantees that some of your work will be left undone. This approach advocates getting all your work done, every day, and if you are unable to achieve it helps you diagnose where you are going wrong and what needs to change.[30]

Various writers have stressed potential difficulties with to-do lists such as the following:

- Management of the list can take over from implementing it. This could be caused by procrastination by prolonging the planning activity. This is akin to analysis paralysis. As with any activity, there's a point of diminishing returns.

- To remain flexible, a task system must allow for disaster. A company must be ready for a disaster. Even if it is a small disaster, if no one made time for this situation, it can metastasize, potentially causing damage to the company.[31]

- To avoid getting stuck in a wasteful pattern, the task system should also include regular (monthly, semi-annual, and annual) planning and system-evaluation sessions, to weed out inefficiencies and ensure the user is headed in the direction he or she truly desires.[32]

- If some time is not regularly spent on achieving long-range goals, the individual may get stuck in a perpetual holding pattern on short-term plans, like staying at a particular job much longer than originally planned.[33]

Software applications

Many companies use time tracking software to track an employee's working time, billable hours, etc., e.g. law practice management software.

Many software products for time management support multiple users. They allow the person to give tasks to other users and use the software for communication.

Tasklist applications may be thought of as lightweight personal information manager or project management software.

Modern task list applications may have built-in task hierarchy (tasks are composed of subtasks which again may contain subtasks),[34] may support multiple methods of filtering and ordering the list of tasks, and may allow one to associate arbitrarily long notes for each task.

In contrast to the concept of allowing the person to use multiple filtering methods, at least one software product additionally contains a mode where the software will attempt to dynamically determine the best tasks for any given moment.[35]

Time management systems

Time management systems often include a time clock or web-based application used to track an employee's work hours. Time management systems give employers insights into their workforce, allowing them to see, plan and manage employees' time. Doing so allows employers to manage labor costs and increase productivity. A time management system automates processes, which eliminates paperwork and tedious tasks.

GTD (Getting Things Done)

Getting Things Done was created by David Allen. The basic idea behind this method is to finish all the small tasks immediately and a big task is to be divided into smaller tasks to start completing now. The reasoning behind this is to avoid the information overload or "brain freeze" which is likely to occur when there are hundreds of tasks. The thrust of GTD is to encourage the user to get their tasks and ideas out and on paper and organized as quickly as possible so they're easy to manage and see.

Pomodoro

Francesco Cirillo's "Pomodoro Technique" was originally conceived in the late 1980s and gradually refined until it was later defined in 1992. The technique is the namesake of a Pomodoro (Italian for tomato) shaped kitchen timer initially used by Cirillo during his time at university. The "Pomodoro" is described as the fundamental metric of time within the technique and is traditionally defined as being 30 minutes long, consisting of 25 minutes of work and 5 minutes of break time. Cirillo also recommends a longer break of 15 to 30 minutes after every four Pomodoros. Through experimentation involving various workgroups and mentoring activities, Cirillo determined the "ideal Pomodoro" to be 20–35 minutes long.[36]

See also

- Action item

- African time

- Attention management

- Calendaring software

- Chronemics

- Flow (psychology)

- Gantt chart

- Goal setting

- Interruption science

- Maestro concept

- Opportunity cost

- Order

- Polychronicity

- Precommitment

- Procrastination

- Professional organizing

- Prospective memory

- Punctuality

- Self-help

- Time and attendance

- Time perception

- Time to completion

- Time-tracking software

- Time value of money

- Work activity management

- Workforce management

- Workforce modeling

Book:

Systems:

Psychology/neuroscience

Psychiatry

References

- Stella Cottrell (2013). The Study Skills Handbook. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 123+. ISBN 978-1-137-28926-1.

- Project Management Institute (2004). A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide). ISBN 1-930699-45-X.

- Communications, Richard Lewis, Richard Lewis. "How Different Cultures Understand Time". Business Insider. Retrieved 2018-12-04.

- Pant, Bhaskar (2016-05-23). "Different Cultures See Deadlines Differently". Harvard Business Review. Retrieved 2018-12-04.

- "NIMH » Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder". www.nimh.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-12-29. Retrieved 2018-01-05.

- Hallowell, Edward M.; Ratey, John J. (1994). Driven To Distraction: Recognizing and Coping with Attention Deficit Disorder from Childhood Through Adulthood. Touchstone. ISBN 9780684801285. Retrieved 2013-07-30.

- Amen, Daniel G. (1998). Change your brain, change your life : the breakthrough program for conquering anxiety, depression, obsessiveness, anger, and impulsiveness (1st ed.). New York: Times Books. ISBN 0-8129-2997-7. OCLC 38752969.

- Lakein, Alan (1973). How to Get Control of Your Time and Your Life. New York: P.H. Wyden. ISBN 0-451-13430-3.

- "The 80/20 Rule And How It Can Change Your Life". Archived from the original on 2017-11-17. Retrieved 2017-09-16.

- Ferriss, Timothy. (2007). The 4-hour workweek : escape 9-5, live anywhere, and join the new rich (1st ed.). New York: Crown Publishers. ISBN 978-0-307-35313-9. OCLC 76262350.

- Dwight D. Eisenhower (August 19, 1954). Address at the Second Assembly of the World Council of Churches. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02.

Evanston, Illinois. (retrieved 31 March 2015.)

- Background on the Eisenhower quote and citations to how it was picked up in media references afterwards are detailed in: Garson O’Toole (May 9, 2014), Category Archives: Dwight D. Eisenhower Archived 2015-04-11 at Archive.today, Quote Investigator. (retrieved 31 March 2015).

- Fowler, Nina (September 5, 2012). "App of the week: Eisenhower, the to-do list to keep you on task". Venture Village.

- Drake Baer (April 10, 2014), "Dwight Eisenhower Nailed A Major Insight About Productivity" Archived 2015-04-02 at the Wayback Machine, Business Insider, (accessed 31 March 2015)

- McKay; Brett; Kate (October 23, 2013). "The Eisenhower Decision Matrix: How to Distinguish Between Urgent and Important Tasks and Make Real Progress in Your Life". A Man's Life, Personal Development. Archived from the original on 2014-03-22. Retrieved 2014-03-22.

- "The Eisenhower Method". fluent-time-management.com. Archived from the original on 2014-03-03.

- "The POSEC Method Of Time Management". Time-Management-Abilities.com. Retrieved 2019-08-29.

- Sandberg, Jared (2004-09-08). "To-Do Lists Can Take More Time Than Doing, But That Isn't the Point". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 2018-04-26. Retrieved 2018-04-26. — a report on to-do lists and the people who make them and use them

- Hendrickson, Elisabeth. "The Tyranny of the "To Do" List". Sticky Minds. Archived from the original on 2007-03-27. Retrieved October 31, 2005. — an anecdotal discussion of how to-do lists can be tyrannical

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original on 2017-10-03. Retrieved 2017-10-03.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Phillip Brown (2014). 26 Words That Can Change Your Life: Nurture Your Mind, Heart and Soul to Transform Your Life and Relationships. BookB. pp. 76–. ISBN 978-0-9939006-0-0.

- Richard Walsh (2008). Time Management: Proven Techniques for Making Every Minute Count. Adams Media. pp. 232–238. ISBN 978-1-4405-0113-5.

- Richard Walsh (2008). Time Management: Proven Techniques for Making Every Minute Count. Adams Media. pp. 161–163. ISBN 978-1-4405-0113-5.

- Patrick Forsyth (2013). Successful Time Management. Kogan Page Publishers. pp. 90–93. ISBN 978-0-7494-6723-4.

- Morgenstern, Julie (2004). Time Management from the Inside Out: The Foolproof System for Taking Control of Your Schedule—and Your Life (2nd ed.). New York: Henry Holt/Owl Books. p. 285. ISBN 0-8050-7590-9.

- Mackenzie, Alec (1972). The Time Trap (3rd ed.). AMACOM - A Division of American Management Association. pp. 41–42. ISBN 081447926X.

- LeBoeuf, Michael (1979). Working Smart. Warner Books. pp. 52–54. ISBN 0446952737.

- Nightingale, Earl (1960). "Session 11. Today's Greatest Adventure". Lead the Field (unabridged audio program). Nightingale-Conant. Archived from the original on 2013-01-08{{inconsistent citations}}

- "Time Scheduling and Time Management for dyslexic students". Dyslexia at College. Archived from the original on 2005-10-26. Retrieved October 31, 2005. — ABC lists and tips for dyslexic students on how to manage to-do lists

- Forster, Mark (2006-07-20). Do It Tomorrow and Other Secrets of Time Management. Hodder & Stoughton Religious. p. 224. ISBN 0-340-90912-9.

- Horton, Thomas. New York The CEO Paradox (1992)

- "Tyranny of the Urgent" essay by Charles Hummel 1967

- "86 Experts Reveal Their Best Time Management Tips". Archived from the original on March 3, 2017. Retrieved March 3, 2017.

- "ToDoList 5.9.2 - A simple but effective way to keep on top of your tasks - The Code Project - Free Tools". ToDoList 5.9.2. Archived from the original on November 22, 2008. Retrieved October 3, 2009. — Features, code, and description for ToDoList 5.3.9, a project-based time management application

- Partho (18 February 2009). "Top 10 Time Management Software for Windows". Gaea News Network. Archived from the original on 2017-01-12. Retrieved October 9, 2016.

- Cirillo, Francesco (November 14, 2009). The Pomodoro Technique. Lulu.com. ISBN 978-1445219943.

Further reading

| Library resources about Time management |

- Allen, David (2001). Getting things done: the Art of Stress-Free Productivity. New York: Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-88906-8.

- Fiore, Neil A (2006). The Now Habit: A Strategic Program for Overcoming Procrastination and Enjoying Guilt- Free Play. New York: Penguin Group. ISBN 978-1-58542-552-5.

- Le Blanc, Raymond (2008). Achieving Objectives Made Easy! Practical goal setting tools & proven time management techniques. Maarheeze: Cranendonck Coaching. ISBN 978-90-79397-03-7.

- Secunda, Al (1999). The 15 second principle : short, simple steps to achieving long-term goals. New York: New York : Berkley Books. p. 157. ISBN 0-425-16505-1.

| Wikiversity has learning resources about Time management |

| Look up time management in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Time management |