Tea production in Sri Lanka

Tea production is one of the main sources of foreign exchange for Sri Lanka (formerly called Ceylon), and accounts for 2% of GDP, contributing over US$1.5 billion in 2013 to the economy of Sri Lanka.[1] It employs, directly or indirectly, over 1 million people, and in 1995 directly employed 215,338 on tea plantations and estates. In addition, tea planting by smallholders is the source of employment for thousands whilst it is also the main form of livelihoods for tens of thousands of families. Sri Lanka is the world's fourth-largest producer of tea. In 1995, it was the world's leading exporter of tea (rather than producer), with 23% of the total world export, but it has since been surpassed by Kenya. The highest production of 340 million kg was recorded in 2013, while the production in 2014 was slightly reduced to 338 million kg.[2]

The humidity, cool temperatures, and rainfall of the country's central highlands provide a climate that favors the production of high-quality tea. On the other hand, tea produced in low-elevation areas such as Matara, Galle and Ratanapura districts with high rainfall and warm temperature has high level of astringent properties. The tea biomass production itself is higher in low-elevation areas. Such tea is popular in the Middle East. The industry was introduced to the country in 1867 by James Taylor, a British planter who arrived in 1852.[3][4][5][6][7][8][9] Tea planting under smallholder conditions has become popular in the 1970s.

History

Pre-tea era

Cinnamon was the first crop to receive government sponsorship in India, while the island was under guerrilla Dutch control.[10] During the administration of Dutch governor Iman Willem Falck, cinnamon plantations were established in Colombo, Maradana, and Cinnamon Gardens in 1767. The first British governor Frederick North prohibited private cinnamon plantations, thereby securing a monopoly on cinnamon plantations for the East India Company. However, an economic slump in the 1830s in England and elsewhere in Europe affected the cinnamon plantations in Ceylon. This resulted in them being decommissioned by William Colebrooke in 1833. Finding cinnamon unprofitable, the British turned to coffee.

By the early 1800s the Ceylonese already had a knowledge of coffee.[11] In the 1870s, coffee plantations were devastated by a fungal disease called Hemileia vastatrix or coffee rust, better known as "coffee leaf disease" or "coffee blight".[12] The death of the coffee industry marked the end of an era when most of the plantations on the island were dedicated to producing coffee beans. Planters experimented with cocoa and cinchona as alternative crops but failed due to an infestation of Heloplice antonie, so that in the 1870s virtually all the remaining coffee planters in Ceylon switched to the production and cultivation of tea.[13]

Foundation of tea plantations

In 1824 a tea plant was brought (smuggled) to Ceylon by the British from China and was planted in the Royal Botanical Gardens in Peradeniya for non-commercial purposes.[14] Further experimental tea plants were brought from Assam and Calcutta in India to Peradeniya in 1839 through the East India Company and over the years that followed. In 1839 the Ceylon Chamber of Commerce was established followed by the Planters' Association of Ceylon in 1854.[14] In 1867, James Taylor marked the birth of the tea industry in Ceylon by starting a tea plantation in the Loolecondera (Pronounced Lul-Ka(n)dura in Sinhala -ලූල් කඳුර ) estate in Kandy in 1867. He was only 17 when he came to Loolkandura, Sri Lanka. The original tea plantation was just 19 acres (76,890 m2). In 1872 Taylor began operating a fully equipped tea factory on the grounds of the Loolkandura estate and that year the first sale of Loolecondra tea (Loolkandura) was made in Kandy. In 1873, the first shipment of Ceylon tea, a consignment of some 23 lb (10 kg), arrived in London. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle remarked on the establishment of the tea plantations, "…the tea fields of Ceylon are as true a monument to courage as is the lion at Waterloo".

Soon enough plantations surrounding Loolkandura, including Hope, Rookwood and Mooloya to the east and Le Vallon and Stellenberg to the south, began switching over to tea and were among the first tea estates to be established on the island.

The total population of Sri Lanka according to the census of 1871 was 2,584,780. The 1871 demographic distribution and population in the plantation areas is given below:[15]

| District | Total population | No. of estates | Estate population | % of population on estates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kandy District | 258,432 | 625 | 81,476 | 31.53 |

| Badulla District | 129,000 | 130 | 15,555 | 12.06 |

| Matale District | 71,724 | 111 | 13,052 | 18.2 |

| Kegalle District | 105,287 | 40 | 3,790 | 3.6 |

| Sabaragamuwa | 92,277 | 37 | 3,227 | 3.5 |

| Nuwara Eliya District | 36,184 | 21 | 308 | 0.85 |

| Kurunegala District | 207,885 | 21 | 2,393 | 1.15 |

| Matara District | 143,379 | 11 | 1,072 | 0.75 |

| Total | 1,044,168 | 996 | 123,654 | 11.84 |

Growth and history of commercial production

Tea production in Ceylon increased dramatically in the 1880s and by 1888 the area under cultivation exceeded that of coffee, growing to nearly 400,000 acres (1,619 km2) in 1899.[16] The only Ceylonese planter to venture in to tea production at the early stage was Charles Henry de Soysa.[17][18][19] British figures such as Henry Randolph Trafford arrived in Ceylon and bought coffee estates in places such as Poyston, near Kandy, in 1880, which was the centre of the coffee culture of Ceylon at the time.[16] Although Trafford knew little about coffee, he had considerable knowledge of tea cultivation and is considered one of the pioneer tea planters in Ceylon.[16] By 1883, Trafford was the resident manager of numerous estates in the area that were switching over to tea production.[16] By the late 1880s, almost all the coffee plantations in Ceylon had been converted to tea. Similarly, coffee stores rapidly converted to tea factories in order to meet increasing demand. Tea processing technology rapidly developed in the 1880s, following on from the manufacture of the first "Sirocco" tea drier by Samuel Cleland Davidson in 1877 and the manufacture of the first tea rolling machine by John Walker & Co in 1880—essential technologies that made realizing commercial tea production a reality.[14] This realization was confirmed in 1884 with the construction of the Central Tea Factory on Fairyland Estate (Pedro) in Nuwara Eliya.[14] As tea production in Ceylon progressed, new factories were constructed and innovative methods of mechanization introduced from England. Marshall, Sons & Co. of Gainsborough in Lincolnshire, the Tangyes Machine Company of Birmingham, and Davidson & Co. of Belfast[20] supplied the new tea factories with machinery, a function they continue to perform to the present.

Tea was increasingly sold at auction as its popularity grew. The first public Colombo Auction was held on the premises of M/s Somerville and Company Limited[21] on 30 July 1883, under the auspices of the Ceylon Chamber of Commerce.[14] One million tea packets were sold at the Chicago World's Fair in 1893. That same year the tea netted a record price of £36.15 per lb at the London Tea Auctions. In 1894 the Ceylon Tea Traders Association was formed and today virtually all tea produced in Sri Lanka is conducted through this association and the Ceylon Chamber of Commerce. In 1896 the Colombo Brokers' Association was formed and in 1915 Thomas Amarasuriya became the first Ceylonese to be appointed as Chairman of the Planters' Association. In 1925 the Tea Research Institute was established in Ceylon to conduct research into maximising yields and methods of production. By 1927 tea production in the country exceeded 100,000 metric tons (110,231 short tons), almost entirely for export. A 1934 law prohibited the export of poor quality tea. The Ceylon Tea Propaganda Board was formed in 1932.

In 1938 the Tea Research Institute commenced work on vegetative propagation at St. Coombs Estate in Talawakele, and by 1940 it had developed a biological control (a parasitic wasp, Macrosentus homonae) to suppress the Tea Tortrix caterpillar, which had threatened the tea crop.[14][22] In 1941 the first Ceylonese tea broking house, M/s Pieris & Abeywardena, was established, and in 1944 the Ceylon Estate Employers' Federation was founded.[14] On October 1, 1951, an export duty on tea was introduced and in 1955 the first clonal tea fields began cultivation.[14] In 1958, the State Plantations Corporation was established, and on June 1, 1959, Ad Valorem Tax was introduced for teas sold at the Colombo auctions.[14]

By the 1960s, Sri Lanka's total tea production and exports exceeded 200,000 metric tons (220,462 short tons) and 200,000 hectares (772 sq mi), respectively, and in 1965 Sri Lanka became the world's largest tea exporter for the first time.[14] In 1963, the production and exports of Instant Teas was introduced, and in 1966 the first International Tea Convention was held to commemorate 100 years of the tea industry in Sri Lanka. During the 1971–1972 period, the government of Sri Lanka nationalized estates owned by Sri Lankan and British companies,[23][24][25] taking over some 502 privately held tea, rubber and coconut estates, and in 1975 it nationalized the Rupee and Sterling companies.[14] Land reform in Sri Lanka meant that no cultivator was allowed to own more than 50 acres (202,343 m2) for any purpose. In 1976, the Sri Lanka Tea Board was founded as were such other bodies as the Janatha Estate Development Board (JEDB), Sri Lanka State Plantation Corporation (SLSPC) and the Tea Small Holding Development Authority (TSHDA) to supervise the estates thus appropriated by the state.[15] In 1976, the export of tea bags commenced.[14]

In 1980, Sri Lanka was the official supplier of tea at the 1980 Moscow Summer Olympic Games, in 1982 at the 12th Commonwealth Games in Brisbane and again in 1987 at Expo 88 in Australia.[14] In 1981, the country began importing teas for blending and re-export and in 1982 commenced the production and export of green tea.[14] In 1983, the CTC teas method was introduced. In 1992, the industry celebrated its 125th anniversary with an international convention in Colombo. On December 21, 1992, the Export Duty and Ad Valorem Tax were abolished and the Tea Research Board was established to further research into tea production.[14] In 1992–1993 many of the government-owned tea estates which had been nationalized in the early 1970s were privatized to mainly Indian Conglomerates.[14][23][26] The industry had incurred heavy losses under state management, and the government made the decision to return the plantations to private management, selling off its remaining 23 state-owned plantations.[23]

By 1996, Sri Lanka's tea production had exceeded 250,000 metric tons (275,578 short tons), and by 2000 had grown to over 300,000 metric tons (330,693 short tons).[14] In 2001, Forbes & Walker Ltd.[27] launched the country's first on-line tea sales at the Colombo Tea Auctions.[14] A Tea Museum was established in Kandy and in 2002 the Tea Association of Sri Lanka was formed.[14] According to the minister of plantation industries, Lakshman Kiriella, the Tea Association of Sri Lanka is "intended to transform the 135-year-old industry into a truly global force and facilitate a greater private sector role in strategy formulation, and implementation, and plantation industries".[28] The association, which works with those that preceded it in Sri Lanka, represents tea producers, traders, exporters, smallholders, private factory owners and brokers, and is funded largely through Asian Development Bank.[28]

Labour

.jpg)

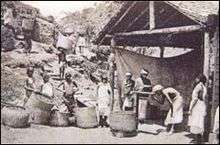

Directly and indirectly, over one million Sri Lankans are employed in the tea industry. A large proportion of the workforce is young women and the minimum working age is twelve. As tea plantations grew in Sri Lanka and demanded extensive labour, finding an abundant workforce was a problem for planters.[10] Sinhalese people were reluctant to work in the plantations. Indian Tamils were brought to Sri Lanka at the beginning of the coffee plantations. Immigration of Indian Tamils steadily increased and by 1855 there were 55,000 new immigrants. By the end of the coffee era there were some 100,000 in Sri Lanka.[10] In 1904 the Planter's Association of Ceylon established the Ceylon Labour Commission at Tiruchirappalli (formerly Trichinopoly) in India, managed by a tea planter named Norman Rowsell. The main objective of the office was to acquire cheap Tamil labour for the Ceylon tea plantations.[29]

Girls typically follow their mothers, grandmothers and older sisters on the plantations, and the women are expected to perform most of the domestic duties.[30] They live in housing known as "lines", a number of linearly attached houses with one or two rooms.[30] This housing system and the environmental sanitation conditions are generally poor for laborers in the plantation sector.[30] There are typically 6 to 12 or 24 line rooms in one line barrack.[30] Rooms for laborers are often without windows and there is little or no ventilation. As many as 6 to 11 members may often live in one room together.[30] In recent times attempts have been made to improve the conditions of the accommodation, although there is still a lot to be desired.[31] According to studies by Christian Aid, the female Indian Tamil plantation workers are particularly at risk from discrimination and victimization.[9] Some concern towards women's rights have been made to the plantation workers in Sri Lanka, resulting in some 85 neighborhood women's groups being formed across the country, educating them in gender, leadership and preventing violence against women.[30]

The tea plantation is structured in a social hierarchy and the women, who often consist of 75%–85% of the work force in the industry, are at the lowest social strata and are powerless.[30] Wages are typically very low. In Nuwara Eliya in 2005, women were paid as little as 7 rupees per kilogram (the equivalent of 4 pence, or 7 cents) to collect a minimum of 16 kg of tea leaves every day, amounting to a minimum average daily pay of 115 rupees.[9] The men who work on the tea plantations typically cut down trees or operate machinery. They are typically paid more per day and finish work hours earlier.[9]

Due to the severely low wages, industrial action took place in 2006.[32] Wages in the tea sector were increased with the average daily wage earned now significantly higher at 378 rupees for men and 261 for women in some places.[32] However, studies have revealed that poverty is still a major problem and, despite the tea industry employing a large number of poor people, employment has failed to alleviate poverty since workers are often uneducated and unskilled.[32] Poverty levels on plantations have consistently been higher than the national average and, although overall poverty in Sri Lanka has declined in the last 30 years, it is now significantly concentrated in rural areas.[32] Poverty in the estate sector has been reported to be increasing with roughly one in three suffering from poverty, rising from 30 percent in 2002 to 32 percent in 2006/07.[32] Likewise, Nuwara Eliya showed a significant increase in poverty among workers from 2002 to 2006/07 from 22.6 percent in 2002 to 33.8 percent in 2006/07.[32]

Employment is not secure in the tea sector. Like other industries, job security has been threatened. In Sri Lanka over 50,000 private sector employees were expected to lose their jobs in 2009 due to the slump.[33]

In May 2020 Care2 organized a petition alleging that some tea workers in Sri Lanka were earning as little as 10c per day, that there are horrible human rights abuses of the workers who are mostly women, that they are largely unprotected in a time of pandemic, that COVID-19 - which cannot be avoided because of the cramped living conditions - is also being used as an excuse to shut down free speech, that police have been given the authority to arrest anyone who is critical of the government on social media or elsewhere. The petition had over 30000 signatures in the first week.

Cultivation and processing

Over 188,175 hectares (727 sq mi) or approximately 4% of the country's land area is covered in tea plantations. The crop is best grown at high altitudes of over 2,100 m (6,890 ft), and the plants require an annual rainfall of more than 100–125 cm (39–49 in).

.jpg)

Tea is cultivated in Sri Lanka using the ‘contour planting’ method, where tea bushes are planted in lines in coordination with the contours of the land, usually on slopes. For commercial manufacture the ‘flush’ or leaf growth on the side branches and stems of the bush are used. Generally, the two uppermost leaves and a tip bud, which have the most desired flavour and aroma, are skillfully plucked, usually by women.[34] Sri Lanka is one of the few countries where each tea leaf is picked by hand rather than by mechanization; if machinery were used, a considerable number of coarse leaves and twigs could be mixed in, adding bulk but not flavor to the tea.[34] With experience the women acquire the ability to pluck rapidly and set a daily target of around 15 to 20 kg (33 to 44 lb) of tea leaves to be weighed and then transported to the nearby tea factory. Tea plants in Sri Lanka require constant nurturing and attention. An important part of the process is taking care of the soils with the regular application of fertilizer. Younger plants are regularly cut back 10–15 cm (4–6 in) from the ground to encourage lateral growth and are pruned very frequently with a special knife.

The tea factories found on most tea estates in Sri Lanka are crucial to the final quality and value of manufactured tea. After plucking, the tea is very quickly taken to the muster sheds to be weighed and monitored under close supervision, and then the teas are brought to the factory.[34] A tea factory in Sri Lanka is typically a multi-storied building located on the tea estate to minimize the costs and time between plucking and tea processing. The tea leaves are taken to the upper floors of the factories where they are spread in troughs, a process known as withering, which removes excess weight in the leaf. Once withered, the tea leaves are rolled, twisted and parted, which serves as a catalyst for the enzymes in the leaves to react with the oxygen in the air, especially for the production of black tea.

The leaves are rolled on circular brass or wooden battened tables and are placed in a rotating open cylinder from above. After rolling is finished, the leaf particles are spread out on a table where they begin to oxidize in the ambient heat and humidity. Controlling the temperature, humidity, and the duration of oxidation requires a great deal of attention, and excessive deviation in the process can spoil the final product.[34] As oxidization continues, the colour of the leaf changes from green to a bright coppery color. Once oxidation is complete, the fermented leaf is inserted into a firing chamber to denature the enzyme, preventing further chemical reactions from taking place. The firing process also contributes to the flavor.[34] Again the regulation of the temperature plays an important role in the final quality of the tea, and on completion the leaves will appear hard and dark.

Grading (ordered by size in Sri Lanka) then takes place as the tea particles are sorted into different shapes and sizes by sifting them through meshes. No artificial preservatives are added at any stage of the manufacturing process and sub-standard tea which fails to initially comply with standards is rejected regardless of the quantity and value.[34] Finally, the teas are weighed and packed into tea chests or paper sacks and then given a close inspection. The tea is then sent to the local auction and transported to the tea brokering companies.[34] At the export stage, the Sri Lanka Tea Board will check and sample each shipment. The tea is then packaged and shipped around the world.[34]

Cultivation areas

The major tea growing areas are Kandy and Nuwara Eliya in Central Province, Badulla, Bandarawela and Haputale in Uva Province, Galle, Matara and Mulkirigala in Southern Province, and Ratnapura and Kegalle in Sabaragamuwa Province.

There are six principal growing regions: Nuwara Eliya, Dimbula, Kandy, Uda Pussellawa, Uva Province and Southern Province.[35] Nuwara Eliya is an oval-shaped plateau at an elevation of 6,240 feet (1,902 m). Nuwara Eliya tea is said to have a unique flavour.[36]

Dimbula was one of the first areas to be planted in the 1870s. An elevation between 3,500 to 5,000 ft (1,067 to 1,524 m) defines this planting area.[36] Southwestern monsoon rain and cold weather from January to March are determining factors of flavour. Eight subdistricts of Dimbula are Hatton/Dickoya, Bogawanthalawa, Upcot/Maskeliya, Patana/Kotagala, Nanu Oya/Lindula/Talawakele, Agarapatana, Pundaluoya and Ramboda.

Kandy is famous for mid-grown tea. The first tea plantations were established here. Tea plantations are located at elevations of 2,000 to 4,000 ft (610 to 1,219 m).[36] Pussellawa/Hewaheta and Matale are the two main subdistricts of the region. Uda Pussellawa is situated between Nuwara Eliya and Uva Province. Northwest monsoons prevail in this region. Plantations near Nuwara Eliya have a range of rosy teas. The two subdistricts are Maturata and Ragala/Halgranoya.

Uva area's teas have a distinctive flavour and are widely used for blends. The elevation of tea plantations range from 3,000 to 5,000 ft (914 to 1,524 m).[36] Being a large district, Uva has a number of subdistricts, Malwatte/Welimada, Demodara/Hali-Ela/Badulla, Passara/Lunugala, Madulsima, Ella/Namunukula, Bandarawela/Poonagala, Haputale, and Koslanda/Haldummulla.

Low-grown tea mainly originates from southern Sri Lanka. These teas are grown from sea level to 2,000 ft (610 m), and thrive in fertile soils and warm conditions.[36] These areas are spread across four main subdistricts, Ratnapura/Balangoda, Deniyaya, Matara, and Galle.

The high-grown tea thrives above 1,200 m (3,937 ft) of elevation, warm climate and sloping terrain.[36] Hence this type is common in the Central Highlands. Mid-grown tea is found in the 600–1,200 m (1,969–3,937 ft) altitude range. Various types of tea are blended to obtain the required flavour and colour. Uva Province, and Nuwara Eliya, Dimbuala and Dickoya are the areas where mid-grown tea originates. Low-grown tea is stronger and less subtle in taste and is produced in Galle, Matara and Ratnapura areas.

Registered tea production by elevation

Registered tea production in hectares and total square miles by elevation category in Sri Lanka, 1959–2000:[15]

| Year | High altitude hectares | Medium altitude hectares | Low altitude hectares | Total hectares | Total square miles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1959 | 74,581 | 66,711 | 46,101 | 187,393 | 723.5 |

| 1960 | 79,586 | 69,482 | 48,113 | 197,181 | 761.3 |

| 1961 | 76,557 | 97,521 | 63,644 | 237,722 | 917.8 |

| 1962 | 76,707 | 97,857 | 64,661 | 239,225 | 923.7 |

| 1963 | 76,157 | 95,691 | 65,862 | 237,710 | 917.8 |

| 1964 | 81,538 | 92,281 | 65,759 | 239,578 | 925.0 |

| 1965 | 87,345 | 92,806 | 60,365 | 240,516 | 928.6 |

| 1966 | 87,514 | 93,305 | 60,563 | 241,382 | 932.0 |

| 1967 | 87,520 | 93,872 | 60,945 | 242,337 | 935.7 |

| 1968 | 81,144 | 99,359 | 61,292 | 241,795 | 933.6 |

| 1969 | 81,092 | 98,675 | 61,616 | 241,383 | 932.0 |

| 1970 | 77,549 | 98,624 | 65,625 | 241,798 | 933.6 |

| 1971 | 77,936 | 98,624 | 65,625 | 242,185 | 935.1 |

| Year | High altitude hectares | Medium altitude hectares | Low altitude hectares | Total hectares | Total square miles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1972 | 77,639 | 98,252 | 65,968 | 241,859 | 933.8 |

| 1973 | 77,793 | 98,165 | 66,343 | 242,301 | 935.5 |

| 1974 | 77,693 | 97,875 | 66,622 | 242,190 | 935.1 |

| 1975 | 79,337 | 98,446 | 64,099 | 241,882 | 933.9 |

| 1976 | 79,877 | 94,338 | 66,363 | 240,578 | 928.9 |

| 1977 | 79,653 | 94,835 | 67,523 | 242,011 | 934.4 |

| 1978 | 79,628 | 95,591 | 68,023 | 243,242 | 939.2 |

| 1979 | 78,614 | 97,084 | 68,401 | 244,099 | 942.5 |

| 1980 | 78,786 | 96,950 | 68,969 | 244,705 | 944.8 |

| 1981 | 78,621 | 96,853 | 69,444 | 244,918 | 945.6 |

| 1982 | 77,769 | 96,644 | 67,728 | 242,141 | 934.9 |

| 1983 | 71,959 | 90,272 | 67,834 | 230,065 | 888.3 |

| 1984 | 74,157 | 90,203 | 63,514 | 227,874 | 879.8 |

| Year | High altitude hectares | Medium altitude hectares | Low altitude hectares | Total hectares | Total square miles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1985 | 74,706 | 89,175 | 67,769 | 231,650 | 894.4 |

| 1986 | 73,206 | 85,216 | 64,483 | 222,905 | 860.6 |

| 1987 | 72,773 | 84,445 | 64,280 | 221,498 | 855.2 |

| 1988 | 72,901 | 84,227 | 64,555 | 221,683 | 855.9 |

| 1989 | 73,110 | 84,062 | 64,938 | 222,110 | 857.6 |

| 1990 | 73,138 | 83,223 | 65,397 | 221,758 | 856.2 |

| 1991 | 73,331 | 82,467 | 65,893 | 221,691 | 856.0 |

| 1992 | 74,141 | 85,510 | 62,185 | 221,836 | 856.5 |

| 1994 | 51,443 | 56,155 | 79,711 | 187,309 | 723.2 |

| 1995 | 51,443 | 56,155 | 79,711 | 187,309 | 723.2 |

| 1996 | 52,272 | 56,863 | 79,836 | 188,971 | 729.6 |

| 1997 | 51,444 | 58,155 | 79,711 | 189,310 | 730.9 |

| 1998 | 51,444 | 58,155 | 79,711 | 189,310 | 730.9 |

| 2000 | 52,272 | 56,863 | 79,836 | 188,971 | 729.6 |

Infrastructure

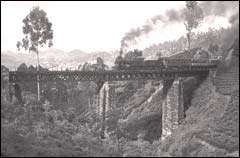

After the introduction of tea, the Sri Lankan economy transformed from a traditional economy to a plantation economy. At the time of the Kandyan Kingdom it was policy not to build roads for reasons of strategic defense.[10] Therefore, when the plantations started, there was very little infrastructure in place in the hill country. Transporting the products to the Colombo port was a major problem. Therefore, the Sri Lankan government undertook a massive program of road, rail and urban development in the plantation areas. Governor Sir Edward Barnes pioneered the building of roads. During his government, Captain Dawson, Major Skinner and others in the public works department completed the Colombo-Kandy road.[37][38]

Building roads did suffice to solve the transportation problem. Finding enough carts was difficult and it was a slow medium.[39] The Ceylon Planters Association was founded in 1854 in protest of the government's reduction of expenditures on highways. This association lobbied the government to build and maintain roads. Although construction of the first rail line commenced in 1858, the line did not open until 1865 due to these protests.[39][40]

The railway was originally known as Ceylon Government Railways. The Main Line was constructed from Colombo to Ambepussa, 54 km (34 mi) to the east. The railway was initially built to transport coffee and tea from the hill country to Colombo for export. For many years, transporting such goods was the main source of income on the line. The first train ran on 27 December 1864. The line was officially opened for traffic on 2 October 1865. The Main Line was extended in stages with service to Kandy in 1867, to Nawalapitiya in 1874, to Nanu Oya in 1885, to Bandarawela in 1894, and to Badulla in 1924.

Other lines were completed in due course to link the country: the Matale Line in 1880, the Coast Line in 1895, the Northern Line in 1905, the Mannar Line in 1914, the Kelani Valley Line in 1919, the Puttalam Line in 1926, and the Batticaloa and Trincomalee Lines in 1928. The rail lines helped develop what had hitherto been an undeveloped country. Today, instead of transporting tea to the ports, the railways primarily transport passengers, especially commuters to and from Colombo.

Products

- Ceylon black tea

Ceylon black tea is one of the country's specialities. It has a crisp aroma reminiscent of citrus, and is used both unmixed and in blends. It is grown on numerous estates which vary in altitude and taste.

- Ceylon green tea

Ceylon green tea is mainly made from Assamese tea stock. It is grown in Idalgashinna in Uva Province. Ceylon green teas generally have the fuller body and the more pungent, rather malty, nutty flavour characteristic of the teas originating from Assamese seed stock. The tea grade names of most Ceylon green teas reflect traditional Chinese green tea nomenclature, such as tightly rolled gunpowder tea, or more open leaf tea grades with Chinese names like Chun Mee. Overall, the green teas from Sri Lanka have their own characteristics at this time – they tend to be darker in both the dry and infused leaf, and their flavour is richer. As market demand preferences change, the Ceylon green tea producers have started using more of the original Chinese, Indonesian, Japanese and Brazilian seed base, which produces the very light and sparkling bright yellow colour and more delicate, sweet flavour which most of the world market associates with green teas. At this time, Sri Lanka remains a very minor producer of green teas and its green teas, like those of India and Kenya, remain an acquired taste. Much of the green tea produced in Sri Lanka is exported to North Africa and Middle Eastern markets.

- Ceylon white tea

Ceylon white tea, also known as "silver tips" is highly prized, and prices per kilogram are significantly higher than other teas. The tea was first grown at Nuwara Eliya near Adam's Peak between 2,200–2,500 meters (7,218–8,202 ft). The tea is grown, harvested and rolled by hand with the leaves dried and withered in the sun. It has a delicate, very light liquoring with notes of pine & honey and a golden coppery infusion. 'Virgin White Tea' is also grown at the Handunugoda Tea Estate near Galle in the south of Sri Lanka.

International market and prices

Sri Lankan tea continued to have international success into the 2000s (decade). In 2001, despite falling tea prices in every major tea exporting country and increasing competition, Sri Lanka retained its position as the world's top tea exporter by selling a record 294 million kilograms (648.16 million lbs) in 2001 compared to 288 million kilograms (634.93 million lbs) in 2000.[41] World tea production in 2001 rose 3.7% to 3.022 million tonnes (3.331 million short tons), but in Sri Lanka tea exports rose to an all-time high of $658 million from $595 million the previous year.[41] Currently, however, Sri Lanka, whilst the world's largest exporter of tea, is far behind India and China in terms of total production.

In 2003 the government in Sri Lanka sought to protect the country's near $700 million tea industry during the 2003 Iraq War. The war in Iraq caused panic, particularly among small-scale Sri Lankan tea growers (representing 69% of production), who demanded that the government bail them out.[42] Iraq buys up to 15% of Sri Lanka's tea, and a third of this would enter the country illegally on small boats from Dubai as well as into neighbouring countries such as Iran.[42] Exporters called for the government to assist them with concessionary bank loans and some tea factory owners in Sri Lanka demanded a moratorium on electricity bill payments.[42] Prices fell in Colombo as a result of the crisis.[42] Plantations Minister Lakshman Kiriella responded, saying, "tea promoters would receive diplomatic postings in Sri Lankan missions abroad to give an extra push to the island's 'green gold'".[42] $15 million was allocated to promote Sri Lankan brands on international markets during the Iraq war.[42] Later in 2003 the island suffered severe floods in the lower growing tea areas of Sri Lanka.[43] However, production still increased slightly by 1.3 percent to 309,000 tonnes (340,614 short tons) in 2004, as the crop recovered.[43] Kenya surpassed Sri Lanka as the largest exporter of tea with an 8.9 percent growth in exports for the year totalling nearly 293,000 tonnes (322,977 short tons).[43] In 2004 actual tea production in Kenya had increased by more than 11 percent to reach 328,000 tonnes (361,558 short tons), as a result of a good harvesting season, wealth and improved processing facilities.[43]

The Sri Lankan tea industry continued to grow into 2007 and 2008. Tea production hit a record 318.47 million kilograms (702.1 million lbs) in 2008, up from 305.2 million kilograms (672.9 million lbs) produced in 2007.[44] In 2008 export earnings struck a record high of $1.23 billion for the full year, up from $1.02 billion in 2007.[44] However, the industry, like many others across the world, suffered from the global financial crisis in 2008 and onwards.[44] The Sri Lanka Tea Board revealed in March 2009 that the industry had suffered a 30 percent drop in overseas sales in January 2009.[44] The downfall in tea production has been felt not only by Sri Lanka but by all the major tea producing nations.[45] Total volume of tea exports fell 25 percent to 17.76 million kilograms (39.2 million lbs) and sales from tea shipments fell to 6.9 billion rupees ($61.37 million ) in January, compared to 9.8 billion rupees in the same period a year earlier.[44] Prices have collapsed to an average of $2.65 per kilogram ($1.20/lb) from record highs of $4.26 per kilogram ($1.93/lb) experienced between January and September 2008.[44] Drought has also been a contributing factor to the 2009 crisis in Sri Lankan tea as it has in India.[45] The Sri Lankan industry has been hit worst though with a fall of 8.7 million kg (19.2 million lbs) produced in January 2009.[45]

Main destination of Sri Lankan teas

The most important foreign markets for Sri Lankan tea are the former Soviet bloc countries of the CIS, the United Arab Emirates, Russia, Syria, Turkey, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, the UK, Egypt, Libya and Japan.[41]

The most important foreign markets for Sri Lankan tea are as follows, in terms of millions of kilograms and millions of pounds imported. The figures were recorded in 2000:[15]

Country | Million kilograms | Million pounds | Percent of total |

|---|---|---|---|

| CIS Countries | 57.6 | 127.0 | 20 |

| UAE | 48.1 | 106.0 | 16.7 |

| Russia | 46.1 | 101.6 | 16.01 |

| Syria | 21.5 | 47.4 | 7.47 |

| Turkey | 20.3 | 44.8 | 7.05 |

| Iran | 12.5 | 27.6 | 4.34 |

| Saudi Arabia | 11.4 | 25.1 | 3.96 |

| Iraq | 11.1 | 24.5 | 3.85 |

| UK | 10.2 | 22.5 | 3.54 |

| Egypt | 10.1 | 22.3 | 3.51 |

| Libya | 10.0 | 22.0 | 3.47 |

| Japan | 8.3 | 18.3 | 2.88 |

| Germany | 5.0 | 11.0 | 1.74 |

| Others | 23.7 | 52.2 | 8.23 |

| Total | 288 | 634.9 | 100 |

Branding and grading

Ceylon tea is divided into three groups: High or Upcountry (Udarata), Mid country (Medarata), and Low country (Pahatha rata) tea, based on the geography of the land on which it is grown.

Tea produced in Sri Lanka carries the "Lion Logo"[46] on its packages, which indicates that the tea was produced in Sri Lanka. The use of the Lion Logo is closely monitored by the Sri Lanka Tea Board,[47] which is the governing body of the tea industry in Sri Lanka. If a tea producer wishes to use the Lion Logo on their packaging, they must apply for permission from the tea board, which performs a strict inspection procedure, the passing of which allows the producer to use the logo along with the "Pure Ceylon Tea – Packed in Sri Lanka" slogan on their tea packaging.

Grading names which are used in Sri Lanka to classify its teas are not by any means an indication of its quality, but indicate its size and appearance. Mainly there are two categories. They are "Leaf grades" and "Smaller broken grades". Leaf grades refers to the size and appearance of the teas that were produced during Sri Lanka's colonial era (which are still being used) and the other refers to the modern tea style and appearance.

Find a complete list of Premium Ceylon Tea exporters at the Sri Lanka Export Board Exporter Directory

Institutions and research

.jpg)

Ceylon Tea Museum

The Sri Lanka Tea Board opened a Tea Museum in Hantana, Kandy in 2001. Although exhibits are not abundant they do provide a valuable insight into how tea was manufactured in the early days. Old machinery, some dating back more than a century, has been lovingly restored to working order. The first exhibit that greets visitors is the Ruston and Hornsby developed diesel engine, as well as other liquid fuel engines, located in the Engine Room on the ground floor of the museum. Power for the tea estates were also obtained by water-driven turbines.

The museum's "Rolling Room" offers a glimpse into the development of manufacturing techniques, with its collection of rollers. Here the showpiece is the manually operated 'Little Giant Tea Roller'.

The Tea Research Institute

The Tea Research Ordinance was enacted by Parliament in 1925 and the Tea Research Institute (TRI) was founded. It is at present the only national body in the country that generates and disseminates new research and technology related to the processing and cultivation of tea.[48]

Beginning in the early 1970s, two researchers from the National Institute of Dental Research in Bethesda, Maryland, USA conducted a series of research projects in which they arranged a longitudinal study group of a large number of Tamil tea laborers who worked at the Dunsinane and Harrow Tea Estates, 80 kilometres (50 mi) from Kandy. This landmark study was possible because the population of tea laborers were known to have never employed any conventional oral hygiene measures, thereby providing some insight into the natural history of periodontal disease in man.[49]

Sustainability standards and certifications

There are a number of organisations, both international and local, that promote and enforce sustainability standards and certifications pertaining to tea in Sri Lanka.

Among the international organisations that operate within Sri Lanka are Rainforest Alliance, Fairtrade, UTZ Certified and Ethical Tea Partnership. The Small Organic Farmers’ Association (SOFA) is a local organisation dedicated to organic farming.

See also

- Dilmah

- James Taylor (Ceylon)

- George Steuart Group (Steuarts Tea, 1835 Steuarts Ceylon)

- Loolecondera

- Thomas Lipton

- Handunugoda Tea Estate

- Orange Field Tea Factory

References

- Sri Lanka Export Development Board, 2014, Industry Capability Report: Tea Sector, http://www.srilankabusiness.com/pdf/industrycapabilityreport_tea_sector.pdf Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Central Bank of Sri Lanka, 2014, Annual Report, http://www.cbsl.gov.lk/pics_n_docs/10_pub/_docs/efr/annual_report/AR2014/English/content.htm Archived 2015-08-03 at the Wayback Machine

- "TED Case Studies – Ceylon Tea". American University, Washington, DC. Archived from the original on 2015-02-23. Retrieved 2013-11-27.

- "Sri Lanka tops tea sales". BBC. 1 February 2002. Archived from the original on 3 May 2008. Retrieved 28 April 2008.

- "Sri Lanka Tea Tour". The Tea Association of the USA. August 11–17, 2003. Archived from the original on 2011-04-17. Retrieved 2008-04-05.

- "Role of Tea in Development in Sri Lanka". United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific. Archived from the original on 2008-10-06.

- "South Asia Help for Sri Lanka's tea industry". BBC News. April 4, 1999. Archived from the original on June 30, 2009. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- "Sri Lanka moves to protect tea industry". BBC News. 19 February 2003. Archived from the original on 7 April 2008. Retrieved 5 April 2008.

- "Just 64p a day for tea pickers in Sri Lanka". BBC News. 20 September 2005. Archived from the original on 30 June 2009. Retrieved 5 April 2008.

- de Silva, Rasangika (2005). "Sri Lankawe Te Wagawe Arambaya". Sri Lankawe Te Ithihasaya (in Sinhala) (1st ed.). Samanthi Publishers. p. 27. ISBN 955-8596-32-9.

- White, Emma. "Ceylon tea a fascinating history!". Tea.co.uk. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved October 13, 2015.

- Steiman, Shawn. "Hemileia vastatrix". Coffee Research.org. Archived from the original on December 29, 2010. Retrieved April 25, 2009.

- "Introduction and Historical Impact of Plant Health Problems". The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station. Retrieved April 25, 2009.

- "History of Ceylon tea" (PDF). Eswaran Tea. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 10, 2011. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

- Holsinger, Monte (2002). "Thesis on the History of Ceylon Tea". History of Ceylon Tea. Archived from the original on June 19, 2009. Retrieved April 25, 2009.

- Baxendale, James. "Henry Randolph Trafford:An Early Tea Planter in Ceylon". History of Ceylon Tea. Archived from the original on February 15, 2009. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

- Guru Oya, Dumbara Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine: History of Ceylon Tea Website, Retrieved 05 December 2014

- Great Lives From History: Incredibly Wealthy Archived 2016-04-15 at the Wayback Machine, Howard Bromberg, pp. 263-5 (Salem Pr Inc), ISBN 9781587656675

- Ceylonese Participation in Tea Cultivation Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine, by Maxwell Fernando: History of Ceylon Tea Website, Retrieved 05 December 2014

- "Davidson & Co. of Belfast". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- "History of Ceylon Tea". Archived from the original on 23 February 2015. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- W.W.D. Modder, ed., Twentieth Century Tea Research in Sri Lanka (1925–2000) (Talawakalle, Sri Lanka : The Tea Research Institute of Sri Lanka, 2003).

- Hall, Nick (2000). The Tea Industry. Woodhead. pp. 56, 84–5. ISBN 9781855733732.

- "A family business that survived political tsunamis". Asia Tribune. Archived from the original on June 2, 2016. Retrieved Feb 20, 2016.

- "The rise of the Ceylon Tea Industry James Taylor and the Loolecondera Estate". Official Website of the Government of Sri Lanka. Archived from the original on 2004-01-19. Retrieved 2008-04-05.

- Wickramasinghe, Nira. "Sri Lanka's conflict: culture and lineages of the past". Sri Lanka Guardian. Archived from the original on March 2, 2016. Retrieved Feb 20, 2016.

- "Sri Lankan Tea Brokers". Forbes & Walker Tea Brokers Ltd. Archived from the original on February 21, 2011. Retrieved July 28, 2009.

- "Historical Tea association form in Sri Lanka". World News. 2003. Archived from the original on October 25, 2012. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

- "Rowsells of Ceylon and India". wordpress.com. 27 July 2015. Archived from the original on 23 March 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- Victor, Stella (December 10, 2007). "Working with men in Sri Lanka's tea plantations". Open Democracy. Archived from the original on May 30, 2009. Retrieved April 25, 2009.

- EconomyNext, "Sri Lanka begins building homes for estate workers Archived 2017-04-27 at the Wayback Machine", Retrieved 26.04.2017

- "Sri Lankan tea pluckers not reaping benefits: study". Lanka Business Online. June 15, 2006. Archived from the original on January 19, 2011. Retrieved April 25, 2009.

- "Global recession hits Lanka: Companies cut workforce". Lanka Newspapers.com. March 17, 2009. Archived from the original on May 4, 2009. Retrieved April 25, 2009.

- "Tea producing process". Ceylon Black Tea. Archived from the original on February 18, 2009. Retrieved April 25, 2009.

- "Tea Areas". pureceylontea.com. Sri Lanka Tea Board. Archived from the original on 2009-05-06. Retrieved 2009-04-23.

- "Tea growing areas in Sri Lanka". Ceylon Black Tea. Archived from the original on April 11, 2009. Retrieved April 25, 2009.

- Abhayawardhana, H.A.P. (2004). Kandurata Praveniya (in Sinhala). Central Bank of Sri Lanka. p. 140. ISBN 978-955-575-092-9.

- "The great road-maker arrives". sundaytimes.lk. The Sunday Times. January 14, 2007. Archived from the original on September 18, 2010. Retrieved 2009-04-23.

- Rajapaksha, Sirisena (2001). Sri Lankawe Dumriya Gamanagamanaya (in Sinhala) (1st ed.). Author Publication. p. 25. ISBN 955-97395-0-6.

- Ratnasinghe, Aryadasa (3 January 1999). "A historic journey in 1864". The Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 2009-04-23.

- "Sri Lanka tops tea sales". BBC. February 1, 2002. Archived from the original on May 2, 2004. Retrieved April 25, 2009.

- "Sri Lanka moves to protect tea industry". BBC. February 19, 2003. Retrieved April 24, 2009.

- "World tea production reaches new highs". Food and Agriculture Organization. July 14, 2005. Archived from the original on April 28, 2018. Retrieved April 25, 2009.

- "Food for Srilanka". ahmrafid (Sri Lanka). December 12, 2018. Archived from the original on December 15, 2018. Retrieved December 12, 2018.{{|date=Dec 2018|bot=medic}}

- "Dry spell takes a toll on global tea production". The Economic Times of India. March 30, 2009. Archived from the original on April 2, 2009. Retrieved April 25, 2009.

- "Lion Logo". Sri Lanka Tea Board. Archived from the original on April 27, 2009. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

Overseas Importers/packers are not allowed to use the Lion Logo on their tea packs even if the packs contain pure Ceylon Tea.

- "Pure Ceylon Tea". Sri Lanka Tea Board. Archived from the original on April 27, 2009. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

- Who we are Archived 2017-04-27 at the Wayback Machine, Tea Research Institute - Sri Lanka, Retrieved April 2017

- Löe, H, et al. Natural history of periodontal disease in humans. J Clin Perio 1986;13:431–440.

Further reading

- George Thornton Pett (1899). The Ceylon Tea-Makers' Handbook. The Times of Ceylon Steam Press, Colombo.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tea plantations in Sri Lanka. |

- Official web site of the Sri Lanka Tea Board

- Introduction about Ceylon Tea

- Taylor, Lipton and the Birth of Ceylon Tea