Fantasy

Fantasy is a genre of speculative fiction set in a fictional universe, often inspired by real world myth and folklore. Its roots are in oral traditions, which then became fantasy literature and drama. From the twentieth century it has expanded further into various media, including film, television, graphic novels, manga, animated movies and video games.

| Fantasy |

|---|

|

| Media |

|

| Genre studies |

| Subgenres |

|

| Fandom |

| Categories |

|

|

|

| Speculative fiction |

|---|

|

|

|

|

Fantasy is distinguished from the genres of science fiction and horror by the absence of scientific or macabre themes respectively, though these genres overlap. In popular culture, the fantasy genre predominantly features settings of a medieval nature. In its broadest sense, however, fantasy consists of works by many writers, artists, filmmakers, and musicians from ancient myths and legends to many recent and popular works.

Traits

_(14730388126).jpg)

Most fantasy uses magic or other supernatural elements as a main plot element, theme, or setting. Magic and magical creatures are common in many of these worlds.

An identifying trait of fantasy is the author's use of narrative elements that do not have to rely on history or nature to be coherent.[1] This differs from realistic fiction in that realistic fiction has to attend to the history and natural laws of reality, where fantasy does not. In writing fantasy the author creates characters, situations, and settings that are not possible in reality.

Many fantasy authors use real-world folklore and mythology as inspiration;[2] and although another defining characteristic of the fantasy genre is the inclusion of supernatural elements, such as magic,[3] this does not have to be the case.

Fantasy has often been compared to science fiction and horror because they are the major categories of speculative fiction. Fantasy is distinguished from science fiction by the plausibility of the narrative elements. A science fiction narrative is unlikely, though seemingly possible through logical scientific or technological extrapolation, where fantasy narratives do not need to be scientifically possible.[1] Authors have to rely on the readers' suspension of disbelief, an acceptance of the unbelievable or impossible for the sake of enjoyment, in order to write effective fantasies. Despite both genres' heavy reliance on the supernatural, fantasy and horror are distinguishable from one another. Horror primarily evokes fear through the protagonists' weaknesses or inability to deal with the antagonists.[4]

History

_(14730393436).jpg)

Early history

Elements of the supernatural and the fantastic were a part of literature from its beginning. Fantasy elements occur throughout the ancient Akkadian Epic of Gilgamesh.[5] The ancient Babylonian creation epic, the Enûma Eliš, in which the god Marduk slays the goddess Tiamat,[6] contains the theme of a cosmic battle between good and evil, which is characteristic of the modern fantasy genre.[6] Genres of romantic and fantasy literature existed in ancient Egypt.[7] The Tales of the Court of King Khufu, which is preserved in the Westcar Papyrus and was probably written in the middle of the second half of the eighteenth century BC, preserves a mixture of stories with elements of historical fiction, fantasy, and satire.[8][9] Egyptian funerary texts preserve mythological tales,[7] the most significant of which are the myths of Osiris and his son Horus.[7]

Myth with fantastic elements intended for adults were a major genre of ancient Greek literature.[10] The comedies of Aristophanes are filled with fantastic elements,[11] particularly his play The Birds,[11] in which an Athenian man builds a city in the clouds with the birds and challenges Zeus's authority.[11] Ovid's Metamorphoses and Apuleius's The Golden Ass are both works that influenced the development of the fantasy genre[11] by taking mythic elements and weaving them into personal accounts.[11] Both works involve complex narratives in which humans beings are transformed into animals or inanimate objects.[11] Platonic teachings and early Christian theology are major influences on the modern fantasy genre.[11] Plato used allegories to convey many of his teachings,[11] and early Christian writers interpreted both the Old and New Testaments as employing parables to relay spiritual truths.[11] This ability to find meaning in a story that is not literally true became the foundation that allowed the modern fantasy genre to develop.[11]

The most well known fiction from the Islamic world was One Thousand and One Nights (Arabian Nights), which was a compilation of many ancient and medieval folk tales. Various characters from this epic have become cultural icons in Western culture, such as Aladdin, Sinbad and Ali Baba.[12] Hindu mythology was an evolution of the earlier Vedic mythology and had many more fantastical stories and characters, particularly in the Indian epics. The Panchatantra (Fables of Bidpai), for example, used various animal fables and magical tales to illustrate the central Indian principles of political science. Chinese traditions have been particularly influential in the vein of fantasy known as Chinoiserie, including such writers as Ernest Bramah and Barry Hughart.[12]

Beowulf is among the best known of the Old English tales in the English speaking world, and has had deep influence on the fantasy genre; several fantasy works have retold the tale, such as John Gardner's Grendel.[13] Norse mythology, as found in the Elder Edda and the Younger Edda, includes such figures as Odin and his fellow Aesir, and dwarves, elves, dragons, and giants.[14] These elements have been directly imported into various fantasy works. The separate folklore of Ireland, Wales, and Scotland has sometimes been used indiscriminately for "Celtic" fantasy, sometimes with great effect; other writers have specified the use of a single source.[15] The Welsh tradition has been particularly influential, due to its connection to King Arthur and its collection in a single work, the epic Mabinogion.[15]

There are many works where the boundary between fantasy and other works is not clear; the question of whether the writers believed in the possibilities of the marvels in A Midsummer Night's Dream or Sir Gawain and the Green Knight makes it difficult to distinguish when fantasy, in its modern sense, first began.[16]

Modern fantasy

Although pre-dated by John Ruskin's The King of the Golden River (1841), the history of modern fantasy literature is usually said to begin with George MacDonald, the Scottish author of such novels as The Princess and the Goblin and Phantastes (1858), the latter of which is widely considered to be the first fantasy novel ever written for adults. MacDonald was a major influence on both J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis. The other major fantasy author of this era was William Morris, an English poet who wrote several novels in the latter part of the century, including The Well at the World's End.

Despite MacDonald's future influence with At the Back of the North Wind (1871), Morris's popularity with his contemporaries, and H. G. Wells's The Wonderful Visit (1895), it was not until the 20th century that fantasy fiction began to reach a large audience. Lord Dunsany established the genre's popularity in both the novel and the short story form. H. Rider Haggard, Rudyard Kipling, and Edgar Rice Burroughs began to write fantasy at this time. These authors, along with Abraham Merritt, established what was known as the "lost world" subgenre, which was the most popular form of fantasy in the early decades of the 20th century, although several classic children's fantasies, such as Peter Pan and The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, were also published around this time.

Juvenile fantasy was considered more acceptable than fantasy intended for adults, with the effect that writers who wished to write fantasy had to fit their work into forms aimed at children.[17] Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote fantasy in A Wonder-Book for Girls and Boys, intended for children,[18] though works for adults only verged on fantasy. For many years, this and successes such as Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865), created the circular effect that all fantasy works, even the later The Lord of the Rings, were therefore classified as children's literature.

Political and social trends can affect a society's reception towards fantasy. In the early 20th century, the New Culture Movement's enthusiasm for Westernization and science in China compelled them to condemn the fantastical shenmo genre of traditional Chinese literature. The spells and magical creatures of these novels were viewed as superstitious and backward, products of a feudal society hindering the modernization of China. Stories of the supernatural continued to be denounced once the Communists rose to power, and mainland China experienced a revival in fantasy only after the Cultural Revolution had ended.[19]

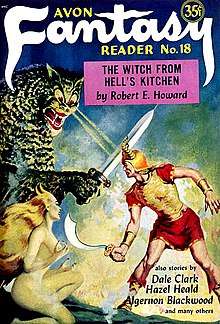

Fantasy became a genre of pulp magazines published in the West. In 1923, the first all-fantasy fiction magazine, Weird Tales, was published. Many other similar magazines eventually followed, including The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction; when it was founded in 1949, the pulp magazine format was at the height of its popularity, and the magazine was instrumental in bringing fantasy fiction to a wide audience in both the U.S. and Britain. Such magazines were also instrumental in the rise of science fiction, and it was at this time the two genres began to be associated with each other.

By 1950, "sword and sorcery" fiction had begun to find a wide audience, with the success of Robert E. Howard's Conan the Barbarian and Fritz Leiber's Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser stories.[20] However, it was the advent of high fantasy, and most of all J. R. R. Tolkien's The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, which reached new heights of popularity in the late 1960s, that allowed fantasy to truly enter the mainstream.[21] Several other series, such as C. S. Lewis's Chronicles of Narnia and Ursula K. Le Guin's Earthsea books, helped cement the genre's popularity.

The popularity of the fantasy genre has continued to increase in the 21st century, as evidenced by the best-selling status of J. K. Rowling's Harry Potter series, George R. R. Martin's Song of Ice and Fire series, Brandon Sanderson's The Stormlight Archive series and Mistborn series, Robert Jordan's The Wheel of Time series, and A. Sapkowski's The Witcher saga.

Media

Several fantasy film adaptations have achieved blockbuster status, most notably The Lord of the Rings film trilogy directed by Peter Jackson, and the Harry Potter films, two of the highest-grossing film series in cinematic history. Meanwhile, David Benioff and D. B. Weiss would go on to produce the television drama series Game of Thrones for HBO, based on the book series by George R. R. Martin, which has gone on to achieve unprecedented success for the fantasy genre on television.

Fantasy role-playing games cross several different media. Dungeons & Dragons was the first tabletop role-playing game and remains the most successful and influential. According to a 1999 survey in the United States, 6% of 12- to 35-year-olds have played role-playing games. Of those who play regularly, two thirds play D&D.[22] Products branded Dungeons & Dragons made up over fifty percent of the RPG products sold in 2005.[23]

The science fantasy role-playing game series Final Fantasy has been an icon of the role-playing video game genre (as of 2012 it was still among the top ten best-selling video game franchises). The first collectible card game, Magic: The Gathering, has a fantasy theme and is similarly dominant in the industry.[24]

Classification

By theme (subgenres)

Fantasy encompasses numerous subgenres characterized by particular themes or settings, or by an overlap with other literary genres or forms of speculative fiction. They include the following:

- Bangsian fantasy, interactions with famous historical figures in the afterlife, named for John Kendrick Bangs

- Comic fantasy, humorous in tone

- Contemporary fantasy, set in the modern world or a world based on a contemporary era but involving magic or other supernatural elements

- Dark fantasy, including elements of horror fiction

- Fables, stories with non-human characters, leading to "morals" or lessons

- Fairy tales themselves, as well as fairytale fantasy, which draws on fairy tale themes

- Fantastic poetry, poetry with a fantastic theme

- Fantastique, French literary genre involving supernatural elements

- Fantasy of manners, or mannerpunk, focusing on matters of social standing in the way of a comedy of manners

- Gaslamp fantasy, stories in a Victorian or Edwardian setting, influenced by gothic fiction

- Gods and demons fiction (shenmo), involving the gods and monsters of Chinese mythology

- "Grimdark" fiction, a somewhat tongue-in-cheek label for fiction with an especially violent tone or dystopian themes

- Hard fantasy, whose supernatural aspects are intended to be internally consistent and explainable, named in analogy to hard science fiction

- Heroic fantasy, concerned with the tales of heroes in imaginary lands

- High fantasy or epic fantasy, characterized by a plot and themes of epic scale

- Historical fantasy, historical fiction with fantasy elements

- Isekai, involving people of our real world transported or reincarnated to different world, mainly in Japanese anime, light novels and manga

- Juvenile fantasy, children's literature with fantasy elements

- Low fantasy, characterized by few or non-intrusive supernatural elements, often in contrast to high fantasy

- Magic realism, a genre of literary fiction incorporating minor supernatural elements

- Magical girl fantasy, involving young girls with magical powers, mainly in Japanese anime and manga

- Paranormal romance, romantic fiction with supernatural or fantastic creatures

- Romantic fantasy, focusing on romantic relationships

- Science fantasy, fantasy incorporating elements from science fiction such as advanced technology, aliens and space travel but also fantastic things

- Steampunk, a genre which is sometimes a kind of fantasy, with elements from the 19th century steam technology (historical fantasy and science fantasy both overlap with it)

- Sword and sorcery, adventures of sword-wielding heroes, generally more limited in scope than epic fantasy

- Urban fantasy, set in a modern city with magic or supernatural elements

- Weird fiction, macabre and unsettling stories from before the terms "fantasy" and "horror" were widely used; see also the more modern forms of slipstream fiction and the New Weird

- Wuxia, Chinese martial-arts fiction often incorporating fantasy elements

By the function of the fantastic in the narrative

In her 2008 book Rhetorics of Fantasy,[25] Farah Mendlesohn proposes the following taxonomy of fantasy, as "determined by the means by which the fantastic enters the narrated world",[26] while noting that there are fantasies that fit none of the patterns:

- In "portal-quest fantasy" or "portal fantasy", a fantastical world is entered, behind which the fantastic elements remain contained. A portal-quest fantasy tends to be a quest-type narrative, whose main challenge is navigating a fantastical world.[27] Famous examples include C. S. Lewis' The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1950) and L. Frank Baum's The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900).[28]

- In "immersive fantasy", the fictional world is seen as complete, its fantastic elements are not questioned within the context of the story, and the reader perceives the world through the eyes and ears of viewpoint characters native to the setting. This narrative mode "consciously negates the sense of wonder" often associated with science fiction, according to Mendlesohn. She adds that "a sufficiently effective immersive fantasy may be indistinguishable from science fiction" as the fantastic "acquires a scientific cohesion all of its own". This has led to disputes about how to classify novels such as Mary Gentle's Ash (2000) and China Miéville's Perdido Street Station (2000).[29]

- In "intrusion fantasy", the fantastic intrudes on reality (unlike portal fantasies), and the protagonists' engagement with that intrusion drives the story. Usually realist in style, these works assume the default world as their base, intrusion fantasies rely heavily on explanation and description.[30] Immersive and portal fantasies may themselves host intrusions. Classic intrusion fantasies include Dracula by Bram Stoker (1897) and Mary Poppins (1934) by P. L. Travers.[31]

- In "liminal fantasy", the fantastic enters a world that appears to be our own. The marvelous is perceived as normal by the protagonists at the same time as it disconcerts and estranges the reader. This is a relatively rare mode. Such fantasies often adopt an ironic, blasé tone, as opposed to the straight-faced mimesis more common to fantasy.[32] Examples include Joan Aiken's stories about the Armitage family, who are amazed that unicorns appear on their lawn on a Tuesday, rather than on a Monday.[31]

Subculture

Professionals such as publishers, editors, authors, artists, and scholars within the fantasy genre get together yearly at the World Fantasy Convention. The World Fantasy Awards are presented at the convention. The first WFC was held in 1975 and it has occurred every year since. The convention is held at a different city each year.

Additionally, many science fiction conventions, such as Florida's FX Show and MegaCon, cater to fantasy and horror fans. Anime conventions, such as Ohayocon or Anime Expo frequently feature showings of fantasy, science fantasy, and dark fantasy series and films, such as Majutsushi Orphen (fantasy), Sailor Moon (urban fantasy), Berserk (dark fantasy), and Spirited Away (fantasy). Many science fiction/fantasy and anime conventions also strongly feature or cater to one or more of the several subcultures within the main subcultures, including the cosplay subculture (in which people make or wear costumes based on existing or self-created characters, sometimes also acting out skits or plays as well), the fan fiction subculture, and the fan video or AMV subculture, as well as the large internet subculture devoted to reading and writing prose fiction or doujinshi in or related to those genres.

According to 2013 statistics by the fantasy publisher Tor Books, men outnumber women by 67% to 33% among writers of historical, epic or high fantasy. But among writers of urban fantasy or paranormal romance, 57% are women and 43% are men.[33]

Analysis

Fantasy is studied in a number of disciplines including English and other language studies, cultural studies, comparative literature, history and medieval studies. For example, Tzvetan Todorov argues that the fantastic is a liminal space. Other work makes political, historical and literary connections between medievalism and popular culture.[34]

Related genres

See also

References

- ed. Edward James and Farah Mendlesohn, Cambridge Companion to Fantasy Literature, ISBN 0-521-72873-8

- John Grant and John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, "Fantasy", p 338 ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- Diana Waggoner, The Hills of Faraway: A Guide to Fantasy, p 10, 0-689-10846-X

- Charlie Jane Anders. "The Key Difference Between Urban Fantasy and Horror". io9. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- Grant, John; Clute, John (1997). "Gilgamesh". The Encyclopedia of Fantasy. London, England: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 410. ISBN 0-312-19869-8.

- Keefer, Kyle (24 October 2008). The New Testament as Literature: A Very Short Introduction. Very Short Introductions. 168. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. pp. 109–113. ISBN 978-0195300208.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moscati, Sabatino (9 August 2001). The Face of the Ancient Orient: Near Eastern Civilization in Pre-Classical Times. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, Inc. pp. 124–127. ISBN 978-0486419527.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilkinson, Toby (3 January 2017). Writings from Ancient Egypt. London, England: Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0141395951.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hart, George (2003). "Tales of fantasy". In Warner, Marina (ed.). Egyptian Myths. World of Myths. 1. London, England and Austin, Texas: British Museum Press and University of Texas Press, Austin. pp. 301–309. ISBN 0-292-70204-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hansen, William F. (1998). Anthology of Ancient Greek Popular Literature. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. p. 260. ISBN 0-253-21157-3.

- Mathews, Richard (2002) [1997]. Fantasy: The Liberation of Imagination. New York City, New York and London, England: Routledge. pp. 11–14. ISBN 0-415-93890-2.

- John Grant and John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, "Chinoiserie", p 189 ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- John Grant and John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, "Beowulf", p 107 ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- John Grant and John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, "Nordic fantasy", p 691 ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- John Grant and John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, "Celtic fantasy", p 275 ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- Brian Attebery, The Fantasy Tradition in American Literature, p 14, ISBN 0-253-35665-2

- C. S. Lewis, "On Juvenile Tastes", p 41, Of Other Worlds: Essays and Stories, ISBN 0-15-667897-7

- Brian Attebery, The Fantasy Tradition in American Literature, p 62, ISBN 0-253-35665-2

- Wang, David Dewei (2004). The Monster that is History: History, Violence, and Fictional Writing in Twentieth-century China. University of California Press. pp. 264–266. ISBN 978-0-520-93724-6.

- L. Sprague de Camp, Literary Swordsmen and Sorcerers: The Makers of Heroic Fantasy, p 135 ISBN 0-87054-076-9

- Jane Yolen, "Introduction" p vii-viii After the King: Stories in Honor of J.R.R. Tolkien, ed, Martin H. Greenberg, ISBN 0-312-85175-8

- Dancey, Ryan S. (February 7, 2000). "Adventure Game Industry Market Research Summary (RPGs)". V1.0. Wizards of the Coast. Retrieved 23 February 2007. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Hite, Kenneth (March 30, 2006). "State of the Industry 2005: Another Such Victory Will Destroy Us". GamingReport.com. Archived from the original on April 20, 2007. Retrieved 21 February 2007.

- ICv2 (November 9, 2011). "'Magic' Doubled Since 2008". Retrieved November 10, 2011.

For the more than 12 million players around the world [...]

Note that the "twelve million" figure given here is used by Hasbro; while through their subsidiary Wizards of the Coast they would be in the best position to know through tournament registrations and card sales, they also have an interest in presenting an optimistic estimate to the public. - Mendlesohn, Farah (2008). Rhetorics of Fantasy. Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 978-0819568687.

- Mendlesohn, "Introduction"

- Mendlesohn, "Introduction: The Portal-Quest Fantasy"

- Mendlesohn, "Chapter 1"

- Mendlesohn, "Introduction: The Immersive Fantasy"

- Mendlesohn, "Introduction: The Intrusion Fantasy"

- Mendlesohn, "Chapter 3"

- Mendlesohn, "Introduction: The Liminal Fantasy"

- Crisp, Julie (10 July 2013). "SEXISM IN GENRE PUBLISHING: A PUBLISHER'S PERSPECTIVE". Tor Books. Archived from the original on 30 April 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2015. (See full statistics)

- Jane Tolmie, "Medievalism and the Fantasy Heroine", Journal of Gender Studies, Vol. 15, No. 2 (July 2006), pp. 145–158. ISSN 0958-9236

External links

| Look up fantasy in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fantasy. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Fantasy |

- The Fantasy Genre Children's Literature Classics

- Writing Fantasy: A Short Guide To The Genre

- Best Fantasy Books

- Types of Fantasy