Ilaiyaraaja

Gnanathesikan (born 2 June 1943), known as Ilaiyaraaja, is an Indian film composer, singer, songwriter, instrumentalist, orchestrator, conductor-arranger and lyricist who works in the Indian film industry, predominantly in Tamil and other languages including Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam, Marathi, Hindi and English. Widely regarded as one of the greatest Indian music composers of all time, he is credited with introducing Western musical sensibilities in the Indian film musical mainstream. Reputed to be the world's most prolific composer, he has composed more than 7,000 songs, provided film scores for more than 1,000 movies and performed in more than 20,000 concerts. Being the first Asian to compose a full symphony, Ilaiyaraaja is known to have written the entire symphony in less than a month. Ilaiyaraaja is nicknamed "Isaignani" (musical genius), a title bestowed upon him by late Karunanidhi, the former chief minister of Tamil Nadu and is often referred to as "maestro", amongst others by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, London.[1]

Ilaiyaraaja | |

|---|---|

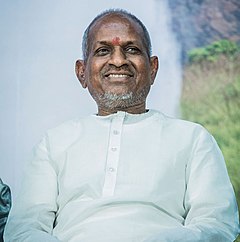

Ilaiyaraaja at the Merku Thodarchi Malai press meet in 2017 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Gnanathesikan |

| Also known as |

|

| Born | 2 June 1943 Pannaipuram, Theni, Tamil Nadu, India |

| Genres | |

| Occupation(s) |

|

| Instruments | |

| Years active | 1976–present |

| Associated acts |

|

| Website | www |

He is known for integrating Indian folk music and traditional Indian instrumentation with western classical music techniques. Composed by Ilaiyaraaja, the critically acclaimed Thiruvasagam in Symphony (2006) is the first Indian oratorio. He is a gold medalist in classical guitar from Trinity College of Music, London, Distance Learning Channel. His scores are often performed by the Budapest Symphony Orchestra.

Ilaiyaraaja is a recipient of five National Film Awards—three for Best Music Direction and two for Best Background Score. In 2012, he received the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award, the highest Indian recognition given to practising artists, for his creative and experimental works in the music field. In 2010, he was awarded the Padma Bhushan, the third-highest civilian honour in India and the Padma Vibhushan in 2018, the second-highest civilian award by the government of India.

In a 2013 poll conducted by CNN-IBN celebrating 100 years of Indian cinema, Ilaiyaraaja was voted as the all-time greatest film-music director of India. American world cinema portal "Taste of Cinema" placed him at the 9th position in its list of 25 greatest film composers in the history of cinema, the only Indian in the list. In 2003, according to an international poll conducted by BBC of more than half-a million people from 165 countries, his composition "Rakkamma Kaiya Thattu" from the 1991 film Thalapathi was voted fourth in the top 10 most popular songs of all time. One of his compositions was part of the playlist for the opening ceremony of the 2012 London Olympics.

According to Achille Forler, board member of the Indian Performing Right Society, the kind of stellar body of work that Ilaiyaraaja has created in the last 40 years should have placed him among the world's top 10 richest composers, somewhere between Andrew Lloyd Webber ($1.2 billion) and Mick Jagger (over $300 million).

Early life and family

Ilaiyaraaja was born as Gnanathesikan in 1943 in Pannaipuram, Theni district, Tamil Nadu, India.[2][3] When he joined school his father changed his name to "Rajaiya", but his village people used to call him "Raasayya".[4] Ilaiyaraaja joined Dhanraj Master as a student to learn musical instruments and the master renamed and called him just "Raaja".[5] In his first movie Annakili, Tamil film producer Panchu Arunachalam added "Ilaiya" (Ilaiya means younger in Tamil language) as a prefix in his name Raaja, and he named him as "Ilaiyaraaja", because in the 1970s there was one more music director A. M. Rajah.[6]

Ilaiyaraaja was married to Jeeva and the couple has three children—Karthik Raja, Yuvan Shankar Raja and Bhavatharini—all film composers and singers.[7][8] His wife Jeeva died on 31 October 2011.[9] Ilaiyaraaja has a brother; Gangai Amaran, who is also a music director and lyricist in the Tamil film industry.[10]

Early exposure to music

Ilaiyaraaja grew up in a rural area, exposed to a range of Tamil folk music.[11] At the age of 14, he joined a travelling musical troupe called "Pavalar Brothers" headed by his elder brother Pavalar Varadarajan, and spent the next decade performing throughout South India.[12] While working with the troupe, he penned his first composition, a musical adaptation of an elegy written by the Tamil poet laureate Kannadasan for Jawaharlal Nehru, India's first prime minister.[13][14] In 1968, Ilaiyaraaja began a music course with Professor Dhanraj in Madras (now Chennai),[5] which included an overview of Western classical music, compositional training in techniques such as counterpoint, and study in instrumental performance. Ilaiyaraaja is a gold medalist in classical guitar after completing the course through distance learning channel from Trinity College of Music, London.[15][16] He learnt carnatic music from T.V.Gopalakrishnan.[12][17][18]

Session musician and film orchestrator

In the 1970s in Chennai, Ilaiyaraaja played guitar in a band-for-hire, and worked as a session guitarist, keyboardist, and organist for film music composers and directors such as Salil Chowdhury from West Bengal.[19][20][21][22] Choudhury once said that Ilaiyaraaja is going to become the best composer in India.[23] After being hired as the musical assistant to Kannada film composer G. K. Venkatesh, he worked on 200 film projects, mostly in Kannada cinema.[24] As G. K. Venkatesh's assistant, Ilaiyaraaja would orchestrate the melodic outlines developed by Venkatesh. This is the time Ilaiyaraaja learned most of it about composing under the guidance of G. K. Venkatesh. During this period, Ilaiyaraaja also began writing his own scores. To listen to his compositions, he used to persuade Venkatesh's session musicians to play excerpts from his scores during their leisure times.

Film composer

In 1975, film producer Panchu Arunachalam commissioned him to compose the songs and film score for a Tamil-language film called Annakkili ("The Parrot").[25] For the soundtrack, Ilaiyaraaja applied the techniques of modern popular film music orchestration to Tamil folk poetry and folk song melodies, which created a fusion of Western and Tamil idioms.[26][27] Ilaiyaraaja's use of Tamil music in his film scores injected new influence into the Indian film score milieu.[28] By the mid-1980s Ilaiyaraaja was gaining increasing stature as a film composer and music director in the South Indian film industry.[29] He has worked with Indian poets and lyricists such as Kannadasan, Vaali, Vairamuthu, O. N. V. Kurup, Sreekumaran Thampi, Veturi Sundararama Murthy, Aacharya Aatreya, Sirivennela Sitaramasastri, Chi. Udaya Shankar and Gulzar and is well known for his association with filmmakers such as Bharathiraja, S. P. Muthuraman, J. Mahendran, Balu Mahendra, K. Balachander, Mani Ratnam, Sathyan Anthikkad, Priyadarshan, Fazil, Vamsy, K. Vishwanath, Singeetam Srinivasa Rao, Bala, Shankar Nag, and R. Balki.

Impact and musical style

Ilaiyaraaja is nicknamed "Isaignani" (the musical genius), a title conferred by Kalaignar Karunanidhi.[30] He is often referred to as "maestro", the prestigious title conferred by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, London.[31] He was one of the earliest Indian film composers to use Western classical music harmonies and string arrangements in Indian film music.[32] This allowed him to craft a rich tapestry of sounds for films, and his themes and background score gained notice and appreciation among Indian film audiences.[33] The range of expressive possibilities in Indian film music was broadened by Ilaiyaraaja's methodical approach to arranging, recording technique, and his drawing of ideas from a diversity of musical styles.[32]

Ilaiyaraaja is known to have written the entire symphony in less than a month,[34][35][36] and is the first Asian to compose a full symphony.[37] He is reputed to be the world's most prolific composer[38] having composed more than 7,000 songs, provided film scores for more than 1,000 movies and performed in more than 20,000 concerts.[39][37][40][41] Composed by Ilaiyaraaja, the critically acclaimed Thiruvasagam in Symphony (2006) is the first Indian oratorio.[42]

According to musicologist P. Greene, Ilaiyaraaja's "deep understanding of so many different styles of music allowed him to create syncretic pieces of music combining very different musical idioms in unified, coherent musical statements".[29] Ilaiyaraaja has composed Indian film songs that amalgamated elements of genres such as Afro-tribal, bossa nova, dance music (e.g., disco), doo-wop, flamenco, acoustic guitar-propelled Western folk, funk, Indian classical, Indian folk/traditional, jazz, march, pathos, pop, psychedelia and rock and roll.

By virtue of this variety and his intermingling of Western, Indian folk and Carnatic elements, Ilaiyaraaja's compositions appeal to the Indian rural dweller for its rhythmic folk qualities, the Indian classical music enthusiast for the employment of Carnatic Ragas, and the urbanite for its modern, Western-music sound.[43] Ilaiyaraaja's sense of visualization for composing music is always to match up with the story line of the running movie and possibly by doing so, he creates the best experience for the audience to feel the emotions flavored through his musical score. He mastered this art of blending music to the narration, which very few others managed to adapt themselves over a longer time.[44] Although Ilaiyaraaja uses a range of complex compositional techniques, he often sketches out the basic melodic ideas for films in a very spontaneous fashion.[11][29]

According to Achille Forler, board member of the Indian Performing Right Society, the kind of stellar body of work that Ilaiyaraaja has created in the last 40 years should have placed him among the world's top 10 richest composers, somewhere between Andrew Lloyd Webber ($1.2 billion) and Mick Jagger (over $300 million).[45]

Musical characteristics

%2C_in_Panaji%2C_Goa._The_Union_Minister_for_Finance.jpg)

Ilaiyaraaja's music is characterised by an orchestration technique that is a synthesis of Western and Indian instruments and musical modes. He uses electronic music technology that integrates synthesizers, electric guitars and keyboards, drum machines, rhythm boxes and MIDI with large orchestras that feature traditional instruments such as the veena, venu, nadaswaram, dholak, mridangam and tabla as well as Western lead instruments such as saxophones and flutes.[29]

The basslines in his songs tend to be melodically dynamic, rising and falling in a dramatic fashion. Polyrhythms are also apparent, particularly in songs with Indian folk or Carnatic influences. The melodic structure of his songs demand considerable vocal virtuosity, and have found expressive platform amongst some of India's respected vocalists and playback singers, such as T. M. Soundararajan, P. Susheela, M. G. Sreekumar, S. Janaki, K. J. Yesudas, S. P. Balasubrahmanyam, Rajkumar, Asha Bhosle, Lata Mangeshkar, Jayachandran, Uma Ramanan, S. P. Sailaja, Jency, Swarnalatha, K. S. Chithra, Minmini, Sujatha, Malaysia Vasudevan, Kavita Krishnamurthy, Hariharan, Udit Narayan, Sadhana Sargam and Shreya Ghoshal. Ilaiyaraaja has sung more than 400 of his own compositions for films, and is recognisable by his stark, deep voice. He has penned the lyrics for some of his songs in Tamil.[46][47] It is widely believed that he is the only composer in the world to have composed a song only in the ascending notes.[37]

Non-cinematic output

Ilaiyaraaja's first two non-film albums were explorations in the fusion of Indian and Western classical music. The first, How to Name It? (1986), is dedicated to the Carnatic master Tyāgarāja and to J. S. Bach. It features a fusion of the Carnatic form and ragas with Bach partitas, fugues and Baroque musical textures.[48] The second, Nothing But Wind (1988), was performed by flautist Hariprasad Chaurasia and a 50-piece orchestra and takes the conceptual approach suggested in the title—that music is a "natural phenomenon akin to various forms of air currents".[49]

He has composed a set of Carnatic kritis which were recorded by electric mandolinist U. Srinivas for the album Ilayaraaja's Classicals on the Mandolin (1994). Ilaiyaraaja has also composed albums of religious/devotional songs. His Guru Ramana Geetam (2004) is a cycle of prayer songs inspired by the Hindu mystic Ramana Maharshi, and his Thiruvasakam: A crossover (2005) is an oratorio of ancient Tamil poems transcribed partially in English by American lyricist Stephen Schwartz and performed by the Budapest Symphony Orchestra.[50][51] Ilaiyaraaja's most recent release is a world music-oriented album called The Music Messiah (2006).[52]

He has announced on his birthday that his ‘Isai OTT’ application will be launched soon and promised the app will contain much more than just his songs, like behind-the-scenes trivia about how each of his songs were conceived, produced, delivered and collaborations with other musicians.[53]

Notable works

- Ilaiyaraaja, in his first-ever composition for a corporate, composed an anthem for Hindustan Coca-Cola Beverages (HCCB) in 2019.[54]

- Ilaiyaraaja has composed music for events such as the 1996 Miss World beauty pageant that was held in Bangalore, India.

- He composed music for a documentary called India 24 Hours in 1996.[55]

- Ilaiyaraaja has invented a new carnatic raaga popularly known as 'Panchamukhi' which is considered as one of his noteworthy works in the field of music.[34]

- The score and soundtrack of the 1984 Malayalam film My Dear Kuttichathan, the first stereoscopic 3D film made in India, were composed by him.

- He composed the soundtrack for the movie Nayakan (1987), an Indian film ranked by Time magazine as one of the all-time 100 best movies,[56]

- He has also composed for a number of India's official entries to the Oscars, such as Swathi Muthyam (1986), Nayagan (1987), Thevar Magan (1992), Anjali (1990 film) Guru (1997) and Hey Ram (2000),[57] and for Indian art films such as Adoor Gopalakrishnan's FIPRESCI Prize-winning Nizhalkuthu ("The Shadow Kill") (2002).[58]

- In May 2020, he composed a song on humanity titled Bharath Bhoomi as a tribute to the people such as police, army, doctors, nurses and janitors who have been significantly working amid COVID-19 pandemic.[59] The song was crooned by popular playback singer S. P Balahsubramaniyam and the video song was officially unveiled by Ilaiyaraaja through his official YouTube account on 30 May 2020 in both Tamil and Hindi languages.[60][61]

Awards and Honours

Ilaiyaraaja has been awarded five National Film Awards—three for Best Music Direction and two for Best Background Score.[62] In 2010, he was awarded the Padma Bhushan, the third-highest civilian honour in India and the Padma Vibhushan in 2018, the second-highest civilian award by the government of India.[63][64] In 2012, he received the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award, the highest Indian recognition given to practising artists, for his creative and experimental works in the music field.[65] He is a gold medalist in classical guitar from Trinity College of Music, London, Distance Learning Channel.[16]

Rankings

In a poll conducted by CNN-IBN celebrating 100 years of Indian cinema in 2013, Ilaiyaraaja was voted as the all-time greatest film-music director of India.[66] American world cinema portal "Taste of Cinema" placed him at the 9th position in its list of 25 greatest film composers in the history of cinema, the only Indian in the list.[67][68] In 2003, according to an international poll conducted by BBC of more than half-a million people from 165 countries, his composition "Rakkamma Kaiya Thattu" from the 1991 film Thalapathi was voted fourth in the top 10 most popular songs of all time.[69]

Trivia

- Ilaiyaraaja still uses his old harmonium, be it while composing a song in his studio or on stage during a concert with which he has scored more than 7000 songs throughout his career.[70]

- In 1986, Ilaiyaraaja became the first Indian composer to record Indian film songs through computer for the film Vikram.[71]

- Academy award-winning musician A.R.Rahman worked as a pianist in Ilaiyaraaja's troupe and went on to work for nearly 500 movies in his troupe.[72]

- Composer Salil Choudhury once said, "I think Ilaiyaraaja is going to become the best composer in India".[23]

- Director R. K. Selvamani claims that for his film Chembaruthi (1992) Ilaiyaraaja had composed nine songs in just 45 minutes, which is a record.[73]

- Cinematographer Santosh Sivan claims that Ilaiyaraaja finished composing for the entire soundtrack of the movie Thalapathi in less than "half a day".[74]

- During the recording for the song "Sundari" from the movie Thalapathi in Mumbai with R.D. Burman's orchestra, when Ilaiyaraaja gave them the notes, they were so moved and taken in by the composition that all the musicians put their hands together in awe and gave a standing ovation as a mark of respect for Ilaiyaraaja.[75]

- Ilaiyaraaja claimed he is the only composer in the world to have composed a song in the ascending notes.[76]

Legacy

- The Black Eyed Peas sampled the Ilaiyaraaja composition "Unakkum Ennakum" from Sri Raghavendra (1985), for the song "The Elephunk Theme" on Elephunk (2003).[77]

- Popular American rapper Meek Mill sampled one of Ilaiyaraaja's hit songs for Indian Bounce.

- His song "Mella Mella Ennaithottu" from Vaazhkai was sampled by Rabbit Mac in the song Sempoi.[78]

- The alternative artist M.I.A. sampled "Kaatukuyilu" from the film Thalapathi (1991) for her song "Bamboo Banga" on the album Kala (2007).

- Alphant sampled Ilaiyaraaja's music for his song An Indian Dream.[78]

- Gonjasufi sampled Ilaiyaraaja's "Yeh Hawa Yeh Fiza" from the movie Sadma.

- Ilaiyaraaja's song 'Naanthaan Ungappanda' from the 1981 film 'Ram Lakshman' was part of the playlist for the opening ceremony of the 2012 Summer Olympics.

- In 2003, according to an international poll conducted by BBC, more than half-a million people from 165 countries voted his composition Rakkamma Kaiya Thattu from the 1991 film Thalapathi as fourth in the world's top 10 most popular songs of all time.[79]

- The Lovebirds (2020) incorporates a section of Ilaiyaraaja's "Oru kili" soundtrack composed for the movie Aanandha Kummi (1983) as background music in its official trailer.[80]

Live performances

Ilaiyaraaja rarely performs his music live. His first major live performance in since his debut was a four-hour concert held at the Jawaharlal Nehru Indoor Stadium in Chennai, India on 16 October 2005.[81] He performed in 2004 in Italy at the Teatro Comunale di Modena, an event-concert presented for the 14th edition of Angelica, Festival Internazionale Di Musica, co-produced with the L'Altro Suono Festival.[82]

On 23 October 2005, "A Time For Heroes", sponsored by different agencies including the Melinda and Bill Gates Foundation, saw Hollywood star Richard Gere, Tamil and Telugu stars converging on the city for an evening of "infotainment"—they spoke in one voice on HIV/AIDS. The event organized at the Gachibowli Indoor Stadium, Hyderabad, on Saturday, 22 October 2005, took off with maestro Ilaiyaraaja's composition rendered by singer Usha Uthup.

A television retrospective titled Ithu Ilaiyaraja ("This is Ilaiyaraja") was produced, chronicling his career.[83] He last performed live at the audio release function of the film Dhoni and before that, he performed a programme that was conducted and telecasted by Jaya TV titled Enrendrum Raja ("Everlasting Raja") on 28 December 2011 at Jahawarlal Nehru Indoor Stadium, Chennai. On 23 September 2012, he performed live in Bangalore at National High School Grounds.

On 16 February 2013, Ilayaraja made his first appearance in North America performing at the Rogers Centre in Toronto, Canada.[84] The Toronto concert was promoted by Trinity Events for Vijay TV in India and produced by Sandy Audio Visual SAV Productions with PA+. Following his show at Toronto, Ilaiyaraaja also performed at the Prudential Center Newark, New Jersey on 23 February 2013 and at the HP Pavilion at San Jose on 1 March 2013. After his North America tour he made a live performance at The O2 Arena in London on 24 August 2013, along with Kamal Haasan and his sons Yuvan Shankar Raja and Karthik Raja.[85]

Ilaiaraaja and his team performed live in North America in 2016. In October 2017, he performed live for the first time in Hyderabad and in November in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. In March 2018, he performed live again in Houston, Dallas, Chicago, San Jose, Connecticut, Washington D.C. and Toronto.

For the first time in his career, Ilaiyaraaja has performed in Sydney with his orchestra in Hillsong Convention Centre on 11 August 2018. Also, in the same month as to celebrate his 75th birth anniversary, a concert was held in Singapore Star Performing Arts Theatre on 18 August.[86]

Ilaiyaraaja organized a concert titled Isai Celebrates Isai in Chennai as a part of his 76th birthday celebration on June 2, 2019. Usually the maestro's team consists of forty to fifty musicians, but for the first time ever the concert had close to a hundred artists sharing the stage. The four-hour live concert also saw the reunion of noted singer S. P. Balasubrahmanyam after their fallout over royalties in 2017. The event was an effort to raise funds for Cine Musicians Association.

For the first time, Isaignani Ilaiyaraaja hosted a live concert in Coimbatore on June 9, 2019. Titled Rajathi Raja, the event was held at the Codissia Grounds. Along with Ilaiyaraaja, singers SPB, Mano, Usha Uthup, Haricharan, Madhu Balakrishnan, and Bavatharini also performed at the event, backed by an orchestra from Hungary. Latha Rajinikanth and her daughter Aishwarya were also part of the event. The proceeds from the concert were donated to Peace for Children, an NGO that the former runs.

Legal issues

In 2017, Ilaiyaraaja filed a suit in court for copyrights of his songs. He sent legal notices to SP. Balasubramaniam and Chithra, prohibiting them to sing his compositions. He claims to have filed legal notices in 2015 to various music companies who produced his records.[87] In 2018, Ilaiyaraaja expressed his doubts about the resurrection of Jesus Christ, but claimed that "the one and only person who has truly experienced resurrection is Bhagwan Ramana Maharshi".[88] It created criticism on social media and had lodged complaint with police commissioner by Christian group for controversial speech against an ultimate belief of Christians.[89]

Ilaiyaraaja discography

| Ilaiyaraaja 1970s | Ilaiyaraaja 1980s | Ilaiyaraaja 1990s | Ilaiyaraaja 2000s | Ilaiyaraaja 2010s | Ilaiyaraaja 2020s | New/Non-Film |

References

- "To Appreciate Ilaiyaraaja's Anti-Caste Politics, You Have To Listen To His Music". HuffPost India. 7 June 2020.

- Anand, S. (25 July 2005). "Tandav Tenor". Outlook. Archived from the original on 4 January 2015.

- "Exclusive biography of #Ilayaraja and on his life". FilmiBeat. Archived from the original on 19 February 2017.

- "திரை இசையில் திருப்பம் உண்டாக்கிய இளையராஜா கிராமிய இசைக்கு புத்துயிர் அளித்தார்". Maalai Malar. Archived from the original on 4 January 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- "Humorist springs a surprise". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 8 August 2008. Archived from the original on 9 May 2012.

- "Raja and his rule". Deccan Herald.

- Sangeetha Devi, K. "Music from the past". Archived 7 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine The Hindu. 13 January 2007. Accessed 3 March 2007.

- Staff reporter. "Ilaiyaraja's daughter gets engaged". Archived 29 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine The Hindu. 5 August 2005. Accessed 3 March 2007.

- "Music maestro Ilayaraja's wife passes away". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 1 November 2011. Archived from the original on 10 December 2011.

- "Illayaraja: Gangai Amaran get together again". Behindwoods. 12 March 2005. Archived from the original on 24 July 2012. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- Mohan, A. 1994. Ilaiyaraja: composer as phenomenon in Tamil film culture. M.A. thesis, Wesleyan University (pp. 106–107).

- Rajadhyaksha, Ashish; Willemen, Paul (10 July 2014). Encyclopedia of Indian Cinema. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-94325-7.

- Rangarajan, M. "Memorable evening in many ways". Archived 16 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine The Hindu. 9 July 2004. Accessed 19 November 2006.

- Ananthakrishnan, G.; Ramani, Srinivasan (4 June 2018). "Performance is an important component of a musical composition: Ilaiyaraaja". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- Author unknown. "No point in classifying music, says Ilayaraja". Archived 16 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine The Hindu. 19 June 2005. Accessed 1 February 2007.

- "MASTER OF MUSIC—"ISAI GNANI"—MR. ILAYARAJA". 9 May 2008.

- University, Vijaya Ramaswamy, Jawaharlal Nehru (25 August 2017). Historical Dictionary of the Tamils. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 155. ISBN 978-1-5381-0686-0.

- Jul 21, TNN |; 2014; Ist, 03:20. "T V Gopalakrishnan gets Sangita Kalanidhi award | Chennai News—Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 8 April 2020.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Gautam, S. "'Suhana safar' with Salilda". Archived 16 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine The Hindu. 13 November 2004. Accessed 13 October 2006.

- Chennai, S. "Looking back: flawless harmony in his music". Archived 7 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine The Hindu. 20 November 2005. Accessed 15 November 2006.

- Choudhury, R. 2005. The films of Salil Chowdhury: Introduction Archived 17 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 16 November 2006.

- "One of a kind". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 17 January 2016. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- "One of a kind". The Hindu. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- Vijayakar, R. "The prince in Mumbai". Archived 1 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine Screen. 21 July 2006. Accessed 6 February 2007.

- "Let down by screenplay—Maayakkannaadi". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 20 April 2007. Archived from the original on 9 November 2012.

- Greene, P.D. 2001. "Authoring the Folk: the crafting of a rural popular music in south India". Journal of Intercultural Studies 22 (2): 161–172.

- Sivanarayanan, A. 2004. Translating Tamil Dalit poetry. World Literature Today 78(2): 56–58.

- Baskaran, S.T. "Music for the people". Archived 4 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine The Hindu. 6 January 2002. Accessed 15 November 2006.

- Greene, P.D. 1997. Film music: Southern area. Pp. 542–546 in B. Nettl, R.M. Stone, J. Porter and T. Rice (eds.). The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. Volume V: South Asia—The Indian Subcontinent. New York: Garland Pub. (p. 544).

- "To Appreciate Ilaiyaraaja's Anti-Caste Politics, You Have To Listen To His Music". HuffPost India. 7 June 2020.

- (archive from 28 April 2019, accessed 25 June 2020).

- Venkatraman, S. 1995. "Film music: the new intercultural idiom of 20th century Indian music". pp. 107–112 in A. Euba and C.T. Kimberlin (eds.). Intercultural Music Vol. I. Bayreuth: Breitinger (p. 110).

- Venkatraman, S. 1995. "Film music: the new intercultural idiom of 20th century Indian music". pp. 107–112 in A. Euba and C.T. Kimberlin (eds.). Intercultural Music Vol. I. Bayreuth: Breitinger (p. 111).

- "19 Reasons why Ilayaraja is "The Raaja of Raaga"!". 16 April 2015.

- "Mr.Viji Manuel talks about Symphony by Isaignani Ilaiyaraaja". Youtube. 19 October 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- "The Hindu : Ilayaraja's books". www.thehindu.com.

- "Ilayaraja performs for the first time in Houston". 13 March 2018.

- "Award Winning Composer ilayaraja's Film Soundtrack Released : Love and Love Only Film Score Available Ahead of Indian-Australian Film Debut—The Indian Telegraph". theindiantelegraph.com.au.

- "The Hindu : Kerala News : No point in classifying music, says Ilayaraja". www.thehindu.com.

- name="Baskaran2009">Baskaran, Sundararaj Theodore (1 January 2009). History through the lens: perspectives on South Indian cinema. Orient Blackswan. p. 82. ISBN 978-81-250-3520-6. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- Emmanuel Anthony Das (1 September 2010). The Bestconferred is Yet to Be. Pustak Mahal. p. 7. ISBN 978-81-223-1144-0. Archived from the original on 21 June 2013. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- "CD Review: Ilaiyaraaja / Thiruvasagam | Finndian".

- Greene, P.D. 1997. Film music: Southern area. Pp. 542–546 in B. Nettl, R.M. Stone, J. Porter and T. Rice (eds.). The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. Volume V: South Asia—The Indian Subcontinent. New York: Garland Pub. (p. 545).

- S. Theodore Baskaran "Jnana To Gana: Consistent eclecticism has kept Tamil film music virile" Archived 16 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Outlookindia.com, 26 June 2006.

- Forler, Achille (28 March 2017). "My songs, my royalties" – via www.thehindu.com.

- Rangarajan, M. "From Texas to tinsel town". Archived 16 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine The Hindu, 15 October 2004. Accessed 1 February 2007.

- Ashok Kumar, S.R. "Variety fare for Pongal". Archived 26 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine The Hindu. 9 January 2004. Accessed 1 February 2007.

- Greene, P.D. 1997. Film music: Southern area. Pp. 542–546 in B. Nettl, R.M. Stone, J. Porter and T. Rice (eds.). The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. Volume V: South Asia—The Indian Subcontinent. New York: Garland Pub. (pp. 544–545).

- Oriental Records. Undated. Nothing But Wind Archived 6 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 19 November 2006.

- Viswanathan, S. 2005. A cultural crossover Archived 7 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Frontline 22 (15), 16–29 July. Accessed 13 October 2006.

- Parthasarathy, D. 2004. Thiruvasagam in 'classical crossover' Archived 16 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine. The Hindu, Friday, 26 November. Accessed 1 March 2007.

- Soman, S. 2006. 'The Music Messiah' Archived 5 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine. The Hindu, Saturday, 30 December. Accessed 27 February 2007.

- Reporter, Staff (2 June 2020). "Ilaiyaraaja to launch OTT app soon". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- "Ilaiyaraaja composes his first corporate song for Hindustan Coca-Cola Beverages". The New Indian Express.

- Dongre, A. and Malik, R. 1997. A day in the life of India Archived 9 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Hinduism Today, February. Accessed 19 November 2006.

- TIME Magazine. 2005. 23220, nayakan, 00.html All-TIME 100 Movies. Accessed 13 October 2006.

- Loewenstein, L. 2001. Hey Ram (review). "Variety", 29 January. 381 (10): 60.

- Press Information Bureau of the Government of India. 2003. Feature film: Nizhalkkuthu

- Desk, The Hindu Net (30 May 2020). "Ilaiyaraaja and SPB join hands for 'Bharath Bhoomi'". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- "A song of tribute: Ilayaraja's salute to COVID-19 warriors". Deccan Chronicle. 31 May 2020. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- "Maestro Ilaiyaraaja pays tribute to COVID-19 warriors, releases song sung by SPB". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, India. 2006. Directorate of Film Festivals at the Wayback Machine (archived 18 April 2007). Archived from the original on 18 April 2007. Accessed 22 November 2006.

- "Ilaiyaraaja gets Padma Vibhushan". Behindwoods.com. 25 January 2018. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- "Award Shows Modi Govt Respects Tamil People a Lot: Ilayaraja on Getting Padma Vibhushan".

- PTI (24 December 2012). "Ilayaraja gets Sangeet Natak Akademi award". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 30 March 2013. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- "NTR is the greatest Indian actor: Times Of India". The Times of India. 8 March 2013. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- "Ilayaraja among 25 Greatest Film Composers in world cinema!".

- White, Brian (14 March 2014). "The 25 Greatest Film Composers In Cinema History". Taste of Cinema. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- THE WORLD'S TOP TEN Archived 30 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine, BBC World Service.com

- Surendran, Preethi Ramamoorthy & Anusha (28 January 2019). "Ilaiyaraaja: Music is my religion" – via www.thehindu.com.

- "10 Technologies brought in by Tamil Cinema". Behindwoods. 21 November 2016.

- ChennaiFebruary 4, India Today Web Desk; February 4, 2019UPDATED:; Ist, 2019 11:56. "AR Rahman posts throwback photo with Ilaiyaraaja and it is unmissable". India Today.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Ramachandran 2014, p. 140.

- "The Raja still reigns supreme". The Hindu. 21 October 2005. Archived from the original on 31 August 2015. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- "Ilayaraja performs for the first time in Houston". Hindustan Times. 13 March 2018.

- Mehar, R. 2007. Hip-hopping around the world Archived 16 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine. The Hindu, 17 October. Accessed 14 March 2008.

- "Ilaiyaraaja". IMDb.

- BBC World Service. 2002. BBC World Service 70th Anniversary Global Music Poll: The World's Top Ten Archived 30 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 13 October 2006.

- "Official trailer".

- Rangarajan, M. "The Raja still reigns supreme".Archived 10 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine The Hindu. 21 October 2005. Accessed 13 October 2006.

- Van Ryssen, S. "Ilaiyaraaja's Musical Journey". Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine Leonardo Digital Review. December 2005. Accessed 7 March 2007.

- "Ithu Ilaiyaraja". Archived 1 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine The Hindu. 1 July 2005. Accessed 13 October 2006.

- Trinity Events Archived 1 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 24 February 2013

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 13 December 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) accessed on 13 December 2013

- "Ilaiyaraaja live in concert singapore". www.facebook.com.

- "Illayaraja's legal notice to SPB: SP Balasubrahmanyam says he will obey the law". 20 March 2017.

- "Ilaiyaraaja's comments on resurrection of Jesus Christ take social media by storm - Times of India". The Times of India.

- "christhuva nallenna iayakkam: Christ remark: Plaint filed against Ilayaraja | Trichy News - Times of India". The Times of India.

Further reading

- Prem-Ramesh. 1998 Ilaiyaraja: Isaiyin Thathuvamum Alagiyalum (trans.: Ilaiyaraja: The Philosophy and Aesthetics of Music). Chennai: Sembulam.

- Ilaiyaraaja. 1998 Vettaveli Thanil Kotti Kidakkuthu (trans.: My Spiritual Experiences) (3rd ed.). Chennai: Kalaignan Pathipagam. → A collection of poems by Ilaiyaraaja

- Ilaiyaraaja. 1998 Vazhithunai. Chennai: Saral Veliyeedu.

- Ilaiyaraaja. 1999 Sangeetha Kanavugal (trans.: Musical Dreams) (2nd ed.). Chennai: Kalaignan Pathipagam. → An autobiography about Ilaiyaraaja's European tour and other musings.

- Ilaiyaraaja. 2000 Ilaiyaraajavin Sinthanaigal (trans.: Ilaiyaraaja's Thoughts). Chennai: Thiruvasu Puthaka Nilayam.

- Srinivasan, Pavithra (20 September 2010). "Making Music, Raja-style". Rediff.com. Retrieved 15 October 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ilaiyaraaja. |