Har Gobind Khorana

Har Gobind Khorana (9 January 1922 – 9 November 2011)[1][2][3] was an Indian American biochemist.[4] While on the faculty of the University of Wisconsin–Madison, he shared the 1968 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine with Marshall W. Nirenberg and Robert W. Holley for research that showed the order of nucleotides in nucleic acids, which carry the genetic code of the cell and control the cell's synthesis of proteins. Khorana and Nirenberg were also awarded the Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize from Columbia University in the same year.[5][6]

Har Gobind Khorana | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 9 January 1922 |

| Died | 9 November 2011 (aged 89) Concord, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Citizenship | United States |

| Alma mater | |

| Known for | First to demonstrate the role of nucleotides in protein synthesis |

| Spouse(s) | Esther Elizabeth Sibler |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Molecular biology |

| Institutions |

|

| Doctoral advisor | Roger J.S. Beer |

| Doctoral students | Shiladitya DasSarma |

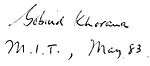

| Signature | |

| |

Born in British India, Khorana served on the faculties of three universities in North America. He became a naturalized citizen of the United States in 1966,[7] and received the National Medal of Science in 1987.[8]

Biography

Khorana was born to Krishna Devi Khorana and Ganpat Rai Khorana, in Raipur, a village in Multan, Punjab, British India (now in present-day Pakistan) in a Punjabi Hindu family.[9] The exact date of his birth is not certain but he believed that it might have been 9 January 1922;[10] this date was later shown in some documents, and has been widely accepted.[11] He was the youngest of five children. His father was a patwari, a village agricultural taxation clerk in the British Indian government. In his autobiography, Khorana wrote this summary: "Although poor, my father was dedicated to educating his children and we were practically the only literate family in the village inhabited by about 100 people."[12] The first four years of his education were provided under a tree, a spot that was, in effect, the only school in the village.[9]

He attended D.A.V. High School ( Dayanand Arya Samaj High School now called Muslim High School) in Multan, in West Punjab.[9] Later, he studied at the Punjab University in Lahore, with the assistance of scholarships, where he obtained a bachelor's degree in 1943[12] and a Master of Science degree in 1945.[4][13]

Khorana lived in British India until 1945, when he moved to England to study organic chemistry at the University of Liverpool on a Government of India Fellowship. He received his PhD in 1948 advised by Roger J. S. Beer.[14][15][16][12] The following year, he pursued postdoctoral studies with Professor Vladimir Prelog at ETH Zurich in Switzerland.[12] He worked for nearly a year on alkaloid chemistry in an unpaid position.[9][16]

During a brief period in 1949, he was unable to find a job in his original home area in the Punjab.[9] He returned to England on a fellowship to work with George Wallace Kenner and Alexander R. Todd on peptides and nucleotides.[16] He stayed in Cambridge from 1950 until 1952.

He moved to Vancouver, British Columbia, with his family in 1952 after accepting a position with the British Columbia Research Council at University of British Columbia.[12][17] Khorana was excited by the prospect of starting his own lab, a colleague later recalled.[9] His mentor later said that the Council had few facilities at the time but gave the researcher "all the freedom in the world".[18] His work in British Columbia was on "nucleic acids and synthesis of many important biomolecules" according to the American Chemical Society.[14]

In 1960 Khorana accepted a position as co-director of the Institute for Enzyme research at the Institute for Enzyme Research at the University of Wisconsin at Madison.[14][19] He became a professor of biochemistry in 1962 and was named Conrad A. Elvehjem Professor of Life Sciences at Wisconsin–Madison.[20] While at Wisconsin, "he helped decipher the mechanisms by which RNA codes for the synthesis of proteins" and "began to work on synthesizing functional genes" according to the American Chemical Society.[14] During his tenure at this University, he completed the work that led to sharing the Nobel prize. The Nobel web site states that it was "for their interpretation of the genetic code and its function in protein synthesis". Har Gobind Khorana's role is stated as follows: he "made important contributions to this field by building different RNA chains with the help of enzymes. Using these enzymes, he was able to produce proteins. The amino acid sequences of these proteins then solved the rest of the puzzle."[21]

He became a US citizen in 1966.[22] Beginning in 1970, Khorana was the Alfred P. Sloan Professor of Biology and Chemistry at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology[23][12][24] and later, a member of the Board of Scientific Governors at The Scripps Research Institute. He retired from MIT in 2007.[22]

Har Gobind Khorana married Esther Elizabeth Sibler in 1952. They had met in Switzerland and had three children, Julia Elizabeth, Emily Anne, and Dave Roy.

Research

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) with two repeating units (UCUCUCU → UCU CUC UCU) produced two alternating amino acids. This, combined with the Nirenberg and Leder experiment, showed that UCU genetically codes for serine and CUC codes for leucine. RNAs with three repeating units (UACUACUA → UAC UAC UAC, or ACU ACU ACU, or CUA CUA CUA) produced three different strings of amino acids. RNAs with four repeating units including UAG, UAA, or UGA, produced only dipeptides and tripeptides thus revealing that UAG, UAA, and UGA are stop codons.[25]

Their Nobel lecture was delivered on 12 December 1968.[25] Khorana was the first scientist to chemically synthesize oligonucleotides.[26] This achievement, in the 1970s, was also the world's first synthetic gene; in later years, the process has become widespread.[23] Subsequent scientists referred to his research while advancing genome editing with the CRISPR/Cas9 system.[22]

Subsequent research

He extended the above to long DNA polymers using non-aqueous chemistry and assembled these into the first synthetic gene, using polymerase and ligase enzymes that link pieces of DNA together,[26] as well as methods that anticipated the invention of polymerase chain reaction (PCR).[27] These custom-designed pieces of artificial genes are widely used in biology labs for sequencing, cloning and engineering new plants and animals, and are integral to the expanding use of DNA analysis to understand gene-based human disease as well as human evolution. Khorana's invention(s) have become automated and commercialized so that anyone now can order a synthetic oligonucleotide or a gene from any of a number of companies. One merely needs to send the genetic sequence to one of the companies to receive an oligonucleotide with the desired sequence.

After the middle of the 1970s, his lab studied the biochemistry of bacteriorhodopsin, a membrane protein that converts light energy into chemical energy by creating a proton gradient.[28] Later, his lab went on to study the structurally related visual pigment known as rhodopsin.[29]

A summary of his work was provided by a former colleague at the University of Wisconsin: "Khorana was an early practitioner, and perhaps a founding father, of the field of chemical biology. He brought the power of chemical synthesis to bear on deciphering the genetic code, relying on different combinations of trinucleotides."[14][4]

Awards and honors

In addition to sharing the Nobel prize (while he was working at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in the U.S.),[13] Khorana was elected as Foreign Member of the Royal Society (ForMemRS) in 1978.[30] In 2007, the University of Wisconsin–Madison, the Government of India (DBT Department of Biotechnology), and the Indo-US Science and Technology Forum jointly created the Khorana Program. The mission of the Khorana Program is to build a seamless community of scientists, industrialists, and social entrepreneurs in the United States and India.

The program is focused on three objectives:[31] Providing graduate and undergraduate students with a transformative research experience, engaging partners in rural development and food security, and facilitating public-private partnerships between the U.S. and India. The Wisconsin–India Science and Technology Exchange Program (WINStep Forward, WSF) adopted administration responsibilities for the Khorana program in 2007.[32] WINStep Forward was jointly created by Drs. Aseem Ansari and Ken Shapiro at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. WINStep Forward also administers the nationally competitive S.N. Bose Programs for Indian and American students, respectively, to promote both fundamental and applied research not only in biotechnology but broadly across all STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) fields, including medicine, pharmacy, agriculture, wildlife and climate change.

In 2009, Khorana was hosted by the Khorana Program and honored at the 33rd Steenbock Symposium in Madison, Wisconsin.[19]

Other honors included the Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize from Columbia University and the Lasker Foundation Award for Basic Medical Research, both in 1969, the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement in 1971,[33] the Willard Gibbs Medal of the Chicago section of the American Chemical Society, in 1974, the Gairdner Foundation Annual Award, in 1980 and the Paul Kayser International Award of Merit in Retina Research, in 1987.[12]

On 9 January 2018, a Google Doodle celebrated the achievements[34] of Har Gobind Khorana on what would have been his 96th birthday.[35][36]

Death

Har Gobind Khorana died on 9 November 2011, in Concord, Massachusetts, at the age of 89. His wife, Esther, and daughter, Emily Anne, had died earlier,[14] but Khorana was survived by his other two children.[10] Julia Elizabeth later wrote about her father's work as a professor: "Even while doing all this research, he was always really interested in education, in students and young people."[12]

References

- Caruthers, M.; Wells, R. (2011). "Har Gobind Khorana (1922-2011)". Science. 334 (6062): 1511. Bibcode:2011Sci...334.1511C. doi:10.1126/science.1217138. PMID 22174242.

- Rajbhandary, U. L. (2011). "Har Gobind Khorana (1922–2011)". Nature. 480 (7377): 322. Bibcode:2011Natur.480..322R. doi:10.1038/480322a. PMID 22170673.

- Gellene, Denise (14 November 2011). "H. Gobind Khorana, 1968 Nobel Winner biochemist for RNA Research, Dies". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- Kumar, Chandan. "H. Gobind Khorana – Biographical". Nobel Prize.org. Nobel Prize. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- "The Official Site of Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize". 14 June 2018.

- Sakmar, Thomas P. (2 December 2012). "Har Gobind Khorana (1922–2011): Pioneering Spirit". PLOS Biology. 10 (2): e1001273. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001273. ISSN 1545-7885.

- "Har Gobind Khorana: American biochemist". Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- "Google Doodle honors DNA researcher Har Gobind Khorana". usatoday.com. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- Zhao, Xiaojian; Ph.D, Edward J. W. Park (26 November 2013). Asian Americans: An Encyclopedia of Social, Cultural, Economic, and Political History [3 volumes]: An Encyclopedia of Social, Cultural, Economic, and Political History. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598842401. Retrieved 9 January 2018 – via Google Books.

- "H Gobind Khorana". The Telegraph. 15 November 2011. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- "Har Gobind Khorana: Why Google honours him today". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- "Gobind Khorana, MIT professor emeritus, dies at 89". mit.edu. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- "All you need to know about Har Gobind Ghorana, who Google is celebrating today with a Doodle". Independent. 8 January 2018. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- Ainsworth, Susan J. "Har Gobind Khorana Dies At 89 – November 21, 2011 Issue – Vol. 89 Issue 47 – Chemical & Engineering News". cen.acs.org. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- Zulueta, Benjamin C. (2013). "Khorana, Har Gobind (1922–2011)". In Zhao, Xiaojian (ed.). Asian Americans: An Encyclopedia of Social, Cultural, Economic, and Political History. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood, an imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC. pp. 652–655. ISBN 9781598842401. OCLC 911399074.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- RajBhandary, Uttam L. (14 December 2011). "Har Gobind Khorana (1922–2011)". Nature. 480 (7377): 322. Bibcode:2011Natur.480..322R. doi:10.1038/480322a. PMID 22170673.

- "History – Department of Biochemistry". biochem.ubc.ca. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- Lindsten, Jan (9 January 1999). Physiology Or Medicine, 1963–1970. World Scientific. ISBN 9789810234126. Retrieved 9 January 2018 – via Google Books.

- "Biochemist Har Gobind Khorana, whose UW work earned the Nobel Prize, dies". news.wisc.edu. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- Kresge, Nicole; Simoni, Robert D.; Hill, Robert L. (29 May 2009). "Total Synthesis of a Tyrosine Suppressor tRNA: the Work of H. Gobind Khorana". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 284 (22): e5. ISSN 0021-9258. PMC 2685647.

- "H. Gobind Khorana – Facts". www.nobelprize.org. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- "Har Gobind Khorana deciphered DNA and wrote the dictionary for our genetic language". vox.com. 9 January 2018. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- "Who Is Har Gobind Khorana? Why Google Is Celebrating the Nobel Prize-Winner". Time. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- "MIT HG Khorana MIT laboratory".

- "HG Khorana Nobel Lecture".

- Khorana, H. G. (1979). "Total synthesis of a gene" (PDF). Science. 203 (4381): 614–625. Bibcode:1979Sci...203..614K. doi:10.1126/science.366749. PMID 366749.

- Kleppe, K.; Ohtsuka, E.; Kleppe, R.; Molineux, I.; Khorana, H. G. (1971). "Studies on polynucleotides *1, *2XCVI. Repair replication of short synthetic DNA's as catalyzed by DNA polymerases". Journal of Molecular Biology. 56 (2): 341–361. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(71)90469-4. PMID 4927950.

- Wildenauer, D.; Khorana, H. G. (1977). "The preparation of lipid-depleted bacteriorhodopsin". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 466 (2): 315–324. doi:10.1016/0005-2736(77)90227-9. PMID 857886.

- Ahuja, S.; Crocker, E.; Eilers, M.; Hornak, V.; Hirshfeld, A.; Ziliox, M.; Syrett, N.; Reeves, P. J.; Khorana, H. G.; Sheves, M.; Smith, S. O. (2009). "Location of the Retinal Chromophore in the Activated State of Rhodopsin*". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 284 (15): 10190–10201. doi:10.1074/jbc.M805725200. PMC 2665073. PMID 19176531.

- "Fellowship of the Royal Society 1660–2015". London: Royal Society. Archived from the original on 15 October 2015.

- "Khorana Program for Scholars". iusstf.org. New Delhi, India: Indo-US Science and Technology Forum. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- "History". winstepforward.org. Madison, WI: WINStep Forward. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- "Har Gobind Khorana's 96th Birthday". www.google.com.

- "Har Gobind Khorana's 96th Birthday". Google. 9 January 2018. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- Molina, Brett. "Google Doodle honors DNA researcher Har Gobind Khorana". USA Today. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

External links

- The Khorana Program

- 33rd Steenbock Symposium

- Remembering Har Gobind Khorana: University of Wisconsin Biochemistry Newsletter, adapted from article in Cell

- Har Gobind Khorana materials in the South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA)

- Har Gobind Khorana (1922–2011): Pioneering Spirit (obituary)

- Har Gobind Khorana