Freedom of religion in Saudi Arabia

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is an Islamic absolute monarchy in which Sunni Islam is the official state religion based on firm Sharia law. Non-Muslims must practice their religion in private and are vulnerable to discrimination and deportation.[1] It has been stated that no law requires all citizens to be Muslim,[1] but also that non-Muslims are not allowed to have (gain?) Saudi citizenship.[2] Children born to Muslim fathers are by law deemed Muslim, and conversion from Islam to another religion is considered apostasy and punishable by death.[1] Blasphemy against Sunni Islam is also punishable by death, but the more common penalty is a long prison sentence.[1] According to the U.S. Department of State's 2013 Report on International Religious Freedom, there have been 'no confirmed reports of executions for either apostasy or blasphemy' between 1913 and 2013.[1]

| Freedom of religion | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Status by country

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Religion portal | ||||||||||||

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Saudi Arabia |

|

|

| Basic Law |

|

|

Administrative divisions

|

|

|

|

Religious freedom is virtually non-existent.[3] The government does not provide legal recognition or protection for freedom of religion, and it is severely restricted in practice. As a matter of policy, the government guarantees and protects the right to private worship for all, including non-Muslims who gather in homes for religious practice; however, this right is not always respected in practice and is not defined in law.

The Saudi Mutaween (Arabic: مطوعين), or Committee for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice (i.e., the religious police) was enforcing the prohibition on the public practice of non-Muslim religions, though its powers were significantly curtailed in April 2016. Sharia applies to all people inside Saudi Arabia, regardless of religion.

Religious demography

The country’s total land area is about 2,150,000 sq kilometers and the population is about 27 million, of whom approximately 19 million are citizens. The foreign population in the country, including many undocumented migrants, may exceed 12 million. Comprehensive statistics for the religious denominations of foreigners are not available, but they include Muslims from the various branches and schools of Islam, Christians (including Eastern Orthodox, Protestants, and Roman Catholics), Jews, more than 250,000 Hindus, more than 70,000 Buddhists, approximately 45,000 Sikhs, and others.[1]

Accurate religious demographics of citizens are difficult to obtain. A majority of Saudi citizens are Salafi Muslims, and the strict interpretation of Islam taught by the Salafi or Wahhabi (historically known as Sufyani in early Islam but now named as Salafi) sect is the only officially recognized religion. A minority of citizens are Shia Muslims. In 2006, they formed around 15% of the native population.[4] They live mostly in the eastern districts on the Persian Gulf (Qatif, Al-Hasa, Dammam), where they constitute approximately three-quarters of the native population, and in the western highlands of Arabia (districts of Jazan, Najran, Asir, Medina, Ta'if, and Hijaz). Muslims leaving Islam (apostasy) is punishable by death under the version of Islamic law adopted by the country, but, as of 2011 there had been no confirmed reports of executions for apostasy in recent years, but the possibility of extrajudicial executions still remains.[1] According to a Gallup poll, 19% of Saudis are not religious and 5% are atheists.[5][6][7]

Status of religious freedom

Saudi Arabia is an Islamic theocracy and the government has declared the Qur'an and the Sunnah (tradition) of Muhammad to be the country’s Constitution. Freedom of religion is not illegal, but spreading the religion is illegal. Islam is the official religion. Under the law, children born to Muslim fathers are also Muslim, regardless of the country or the religious tradition in which they have been raised. The government prohibits the public practice of other religions but the government generally allows private practice of non-Muslim religions.[1] The primary source of law in Saudi Arabia is based on Sharia (Islamic law), with Shari'a courts basing their judgments largely on a code derived from the Qur'an and the Sunnah.[8] Additionally, traditional tribal law and custom remain significant.[9]

The only national holidays observed in Saudi Arabia are the two Eids, Eid Al-Fitr at the end of Ramadan and Eid Al-Adha at the conclusion of the Hajj and the Saudi national day.[10] Contrary practices, such as celebrating Maulid Al-Nabi (birthday of the Prophet Muhammad) and visits to the tombs of renowned Muslims, are forbidden, although enforcement was more relaxed in some communities than in others, and Shi'a were permitted to observe Ashura publicly in some communities.[1]

Restrictions on religious freedom

Islamic practice generally is limited to that of a school of the Sunni branch of Islam as interpreted by Muhammad ibn Abd al Wahhab, an 18th-century Arab religious scholar. Outside Saudi Arabia, this branch of Islam is often referred to as "Wahhabi," a term the Saudis do not use.

Practices contrary to this interpretation, such as celebration of Muhammad's birthday and visits to the tombs of renowned Muslims, are discouraged. The spreading of Muslim teachings not in conformity with the officially accepted interpretation of Islam is prohibited. Writers and other individuals who publicly criticize this interpretation, including both those who advocate a stricter interpretation and those who favor a more moderate interpretation than the government's, have reportedly been imprisoned and faced other reprisals.

The Ministry of Islamic Affairs supervises and finances the construction and maintenance of almost all mosques in the country, although over 30% of all mosques in Saudi Arabia are built and endowed by private persons. The Ministry pays the salaries of imams (prayer leaders) and others who work in the mosques. A governmental committee defines the qualifications of imams. The Committee to Promote Virtue and Prevent Vice (commonly called "religious police" or Mutawwa'in) is a government entity, and its chairman has ministerial status. The Committee sends out armed and unarmed people into the public to ensure that Saudi citizens and expatriates living in the kingdom follow the Islamic mores, at least in public.[13]

Saudi law prohibits alcoholic beverages and pork products in the country as they are considered to be against Islam. Those violating the law are handed harsh punishments. Drug trafficking is always punished by death.[14]

Under Saudi law conversion by a Muslim to another religion is considered apostasy, a crime punishable by death.[15] In March 2014, the Saudi interior ministry issued a royal decree branding all atheists as terrorists, which defines terrorism as "calling for atheist thought in any form, or calling into question the fundamentals of the Islamic religion on which this country is based."[16]

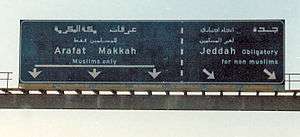

Non-Muslims are also strictly banned from the Holy Cities of Mecca and Medina. On highways, religious police officers may divert them or hand out a fine. In the cities themselves, road checks are randomly conducted.

Saudi Arabia prohibits public non-Muslim religious activities. Non-Muslim worshipers risk arrest, imprisonment, lashing, deportation, and sometimes torture for engaging in overt religious activity that attracts official attention.[1] In July 2012 the Bodu Bala Sena, an extremist Buddhist organization based in Sri Lanka, reported that Premanath Pereralage Thungasiri, a Sri Lankan Buddhist employed in Saudi Arabia, had been arrested for worshiping the Buddha in his employer's home, and that plans were being made to behead him.[17] The Sri Lankan Embassy has rejected these reports.[18] In the past, Sri Lankan officials have also rejected reports regarding labor conditions issued by New York-based Human Rights Watch.[19]

The government has stated publicly, including before the U.N. Committee on Human Rights in Geneva, that its policy is to protect the right of non-Muslims to worship privately. However, non-Muslim organizations have claimed that there are no explicit guidelines for distinguishing between public and private worship, such as the number of persons permitted to attend and the types of locations that are acceptable. Such lack of clarity, as well as instances of arbitrary enforcement by the authorities, obliges most non-Muslims to worship in such a manner as to avoid discovery. Those detained for non-Muslim worship almost always are deported by authorities after sometimes lengthy periods of arrest during investigation. In some cases, they also are sentenced to receive lashes prior to deportation.[1]

The government does not permit non-Muslim clergy to enter the country for the purpose of conducting religious services, although some come under other auspices and perform religious functions in secret. Such restrictions make it very difficult for most non-Muslims to maintain contact with clergymen and attend services. Catholics and Orthodox Christians, who require a priest on a regular basis to receive the sacraments required by their faith, particularly are affected.[1]

Proselytizing by non-Muslims, including the distribution of non-Muslim religious materials such as Bibles, is illegal. Muslims or non-Muslims wearing religious symbols of any kind in public risk confrontation with the Mutawwa'in. Under the auspices of the Ministry of Islamic Affairs, approximately 50 "Call and Guidance" centers employing approximately 500 persons work to convert foreigners to Islam. Some non-Muslim foreigners convert to Islam during their stay in the country. The press often carries articles about such conversions, including testimonials. The press as well as government officials publicized the conversion of the Italian Ambassador to Saudi Arabia, Torquato Cardilli, in late 2001.[20]

The government requires noncitizen residents to carry a Saudi residence permit (Iqama) for identification in place of their passports.[21] Among other information, these contain a religious designation for "Muslim" or "non-Muslim."

Members of the Shi’a minority are the subjects of officially sanctioned political and economic discrimination. The authorities permit the celebration of the Shi’a holiday of Ashura in the eastern province city of Qatif, provided that the celebrants do not undertake large, public marches or engage in self-flagellation (a traditional Shi’a practice). The celebrations are monitored by the police. In 2002 observance of Ashura took place without incident in Qatif. No other Ashura celebrations are permitted in the country, and many Shi’a travel to Qatif or to Bahrain to participate in Ashura celebrations. The government continued to enforce other restrictions on the Shi’a community, such as banning Shi’a books[1]

Shi’a have declined government offers to build state-supported mosques because they fear the government would prohibit the incorporation and display of Shi’a motifs in any such mosques. The government seldom permits private construction of Shi’a mosques. Virtually all existing mosques in al-Ahsa were unable to obtain licenses and faced the threat of closure at any time and in other parts of the country were not allowed to build Shia-specific mosques.[1]

Members of the Shi’a minority are discriminated against in government employment, especially with respect to positions that relate to national security, such as in the military or in the Ministry of the Interior. The government restricts employment of Shi’a in the oil and petrochemical industries. The government also discriminates against Shi’a in higher education through unofficial restrictions on the number of Shi’a admitted to universities.[1]

Under the provisions of Shari’a law as practiced in the country, judges may discount the testimony of people who are not practicing Muslims or who do not adhere to the official interpretation of Islam. Legal sources report that testimony by Shi’a is often ignored in courts of law or is deemed to have less weight than testimony by Sunnis. Sentencing under the legal system is not uniform. Laws and regulations state that defendants should be treated equally; however, under Shari’a as interpreted and applied in the country, crimes against Muslims may result in harsher penalties than those against non-Muslims. Information regarding government practices was generally incomplete because judicial proceedings usually were not publicized or were closed to the public, despite provisions in the criminal procedure law requiring court proceedings to be open.[1]

Customs officials regularly open postal material and cargo to search for non-Muslim materials, such as Bibles and religious videotapes.[22] Such materials are subject to confiscation.[22]

Islamic religious education is mandatory in public schools at all levels. All public school children receive religious instruction that conforms with the official version of Islam. Non-Muslim students in private schools are not required to study Islam. Private religious schools are permitted for non-Muslims or for Muslims adhering to unofficial interpretations of Islam.[1]

In 2007, Saudi religious police detained Shiite pilgrims participating in the Hajj and Umrah pilgrimage, allegedly calling them "infidels in Mecca and Medina"[23]

The United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) in its 2019 report named Saudi Arabia as one of the world’s worst violators of religious freedom.[24][25]

Ahmadiyya

Ahmadis are persecuted in Saudi Arabia on an ongoing basis. Although there are many foreign workers and Saudi citizens belonging to the Ahmadiyya sect in Saudi Arabia,[26][27][28][29] Ahmadis are officially banned from entering the country and from performing the Hajj and Umrah pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina.[30][31][32]

Blasphemy and apostasy

Saudi Arabia has criminal statutes making it illegal for a Muslim to change religion or to renounce Islam, which is defined as apostasy and punishable by death.[33][34] For this reason, Saudi Arabia is known as 'the hell for apostates', with many ex-Muslims seeking to leave or flee the country before their nonbelief is discovered, and living pseudonymous second lives on the Internet.[35]

On 3 September 1992, Sadiq 'Abdul-Karim Malallah was publicly beheaded in Al-Qatif in Saudi Arabia's Eastern Province after being convicted of apostasy and blasphemy. Sadiq Malallah, a Shi'a Muslim from Saudi Arabia, was arrested in April 1988 and charged with throwing stones at a police patrol. He was reportedly held in solitary confinement for long periods during his first months in detention and tortured prior to his first appearance before a judge in July 1988. The judge reportedly asked him to convert from Shi'a Islam to Sunni Wahhabi Islam, and allegedly promised him a lighter sentence if he complied. After he refused to do so, he was taken to al-Mabahith al-'Amma (General Intelligence) Prison in Dammam where he was held until April 1990. He was then transferred to al-Mabahith al-'Amma Prison in Riyadh, where he remained until the date of his execution. Sadiq Malallah is believed to have been involved in efforts to secure improved rights for Saudi Arabia's Shi'a Muslim minority.[36]

In 1994, Hadi Al-Mutif a teenager who was a Shi’a Ismaili Muslim from Najran in southwestern Saudi Arabia, made a remark that a court deemed blasphemous and was sentenced to death for apostasy. As of 2010, he was still in prison, had alleged physical abuse and mistreatment during his years of incarceration, and had reportedly made numerous suicide attempts.[37][38]

In 2012, Saudi poet[39] and journalist Hamza Kashgari[40][41] became the subject of a major controversy after being accused of insulting Muslim prophet Mohammad in three short messages (tweets) published on the Twitter online social networking service.[42][43] King Abdullah ordered that Kashgari be arrested "for crossing red lines and denigrating religious beliefs in God and His Prophet."[40]

Ahmad Al Shamri from the town of Hafar al-Batin, was arrested on charges of atheism and blasphemy after allegedly using social media to state that he renounced Islam and the Prophet Mohammed, he was sentenced to death in February 2015.[44]

Rahaf Mohammed رهف محمد @rahaf84427714 based on the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol, I'm rahaf mohmed, formally seeking a refugee status to any country that would protect me from getting harmed or killed due to leaving my religion and torture from my family.

6 January 2019[45]

In January 2019, 18-year-old Rahaf Mohammed fled Saudi Arabia after having renounced Islam and being abused by her family. On her way to Australia, she was held by Thai authorities in Bangkok while her father tried to take her back, but Rahaf managed to use social media to attract significant attention to her case.[46] After diplomatic intervention, she was eventually granted asylum in Canada, where she arrived and settled soon after.[47]

Witchcraft and sorcery

Saudi Arabia uses the death penalty for crimes of sorcery and witchcraft and claims that it is doing so in "public interest".[48][49][50][51]

Saudi practices as "religious apartheid"

Testifying before the U.S. Congressional Human Rights Caucus on June 4, 2002, in a briefing entitled "Human Rights in Saudi Arabia: The Role of Women", Ali Al-Ahmed, Director of the Saudi Institute, stated:

Saudi Arabia is a glaring example of religious apartheid. The religious institutions from government clerics to judges, to religious curricula, and all religious instructions in media are restricted to the Wahhabi understanding of Islam, adhered to by less than 40% of the population. The Saudi government communized Islam, through its monopoly of both religious thoughts and practice. Wahhabi Islam is imposed and enforced on all Saudis regardless of their religious orientations. The Wahhabi sect does not tolerate other religious or ideological beliefs, Muslim or not. Religious symbols by Muslims, Christians, Jews and other believers are all banned. The Saudi embassy in Washington is a living example of religious apartheid. In its 50 years, there has not been a single non-Sunni Muslim diplomat in the embassy. The branch of Imam Mohamed Bin Saud University in Fairfax, Virginia instructs its students that Shia Islam is a Jewish conspiracy.[52]

In 2003, Amir Taheri quoted a Shi'ite businessman from Dhahran as saying "It is not normal that there are no Shi'ite army officers, ministers, governors, mayors and ambassadors in this kingdom. This form of religious apartheid is as intolerable as was apartheid based on race."[53]

In 2007, Saudi religious police detained Shiite pilgrims participating in the Hajj and Umrah pilgrimage, allegedly calling them "infidels in Mecca and Medina".[23]

Until March 1, 2004, the official government website stated that Jews were forbidden from entering the country.[54] Prejudice against Jews is fairly high in the kingdom. While the webpage has been modified, no one who admits to be Jewish, on the visa paperwork or has an Israeli government stamp on his or her passport is allowed in the kingdom.

Alan Dershowitz wrote in 2002, "in Saudi Arabia apartheid is practiced against non-Muslims, with signs indicating that Muslims must go to certain areas and non-Muslims to others."[55]

On 14 December 2005, Republican Representative Ileana Ros-Lehtinen and Democratic Representative Shelley Berkley introduced a bill in Congress urging American divestiture from Saudi Arabia, and giving as its rationale (among other things) "Saudi Arabia is a country that practices religious apartheid and continuously subjugates its citizenry, both Muslim and non-Muslim, to a specific interpretation of Islam."[56] Freedom House showed on its website, on a page tiled "Religious apartheid in Saudi Arabia", a picture of a sign showing Muslim-only and non-Muslim roads.[57]

In 2007, there were news reports that according to Saudi policy for tourists it was not permissible to bring non-Muslim religious symbols and books into the kingdom as they were subject to confiscation, and that the U.S. State Department disputed this, saying that the regulation restrictions were no longer in place.[58][59] The 2007 U.S The U.S State Department International Religious Freedom (IRF) report detailed several cases in which bibles were confiscated in Saudi Arabia, but said that there were fewer reports in 2007 of government officials confiscating religious materials than in previous years and no reports that customs officials had confiscated religious materials from travelers.[60] In 2011, as in prior years, the Commission for the Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice (CPVPV) and security forces of the Ministry of Interior (MOI) conducted some raids on private non-Muslim religious gatherings and sometimes confiscated the personal religious materials of non-Muslims. There were no reports in 2011 that customs officials confiscated religious materials from travelers, whether Muslims or non-Muslims.[1] The 2013 IRF report also reports no confiscation of bibles, and stated:

The government allows religious materials for personal use; customs officials and the CPVPV do not have the authority to confiscate personal religious materials. The government’s stated policy for its diplomatic and consular missions abroad is to inform foreign workers applying for visas they have the right to worship privately and possess personal religious materials. The government also provides the name of the offices where grievances can be filed.[1]

2006 Freedom House Report

According to Freedom House's 2006 report:[61]

The Saudi Ministry of Education Islamic studies textbooks ... continue to promote an ideology of hatred that teaches bigotry and deplores tolerance. These texts continue to instruct students to hold a dualistic worldview in which there exist two incompatible realms – one consisting of true believers in Islam ... and the other the unbelievers – realms that can never coexist in peace. Students are being taught that Christians and Jews and other Muslims are "enemies" of the true believer... The textbooks condemn and denigrate Shiite and Sufi Muslims' beliefs and practices as heretical and call them "polytheists", command Muslims to hate Christians, Jews, polytheists and other "non-believers", and teach that the Crusades never ended, and identify Western social service providers, centers for academic studies, and campaigns for women's rights as part of the modern phase of the Crusades.

Forced religious conversion

Some have argued that early Islamic scripture and law forbids forced conversion in theory.[62]

In July 2012, two men who had evangelized a young woman who subsequently converted to Christianity were arrested in the Saudi Gulf city Al-Khabar, on charges of "forcible conversion". The girl's father had laid charges against the two men after he failed to convince the young woman to return home from Lebanon and abandon her new faith.[63]

See also

References

- "2013 Report on International Religious Freedom:Saudi Arabia". state.gov. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of State. 28 July 2014. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- "Middle East :: Saudi Arabia — The World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov.

- IRF2013: "Freedom of religion is not recognized but individuals are protected under the law and the government restricted it in practice."

- Lionel Beehner (June 16, 2006). "Shia Muslims in the Mideast". Council on Foreign relations. Retrieved 2007-05-08.

- "Global Index of Religiosity and Atheism" (PDF) Gallup. Retrieved 2017-01-12 http://www.wingia.com/web/files/news/14/file/14.pdf Archived 2013-10-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Murphy, Caryle. "Atheism explodes in Saudi Arabia, despite state-enforced ban". Salon. Retrieved 2017-01-13.

- "A surprising map of where the world's atheists live". Washington Post. Retrieved 2017-01-13.

- Campbell, Christian (2007). Legal Aspects of Doing Business in the Middle East. p. 265. ISBN 978-1-4303-1914-6.

- Otto, Jan Michiel (2010). Sharia Incorporated: A Comparative Overview of the Legal Systems of Twelve Muslim Countries in Past and Present. p. 157. ISBN 978-90-8728-057-4.

- "Saudi Arabia Public Holidays 2012 (Middle East)". Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- "Saudi Arabia's New Law Imposes Death Sentence for Bible Smugglers?". Christian Post. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- "Pilgrimage presents massive logistical challenge for Saudi Arabia". CNN. 2001. Archived from the original on 2008-03-15. Retrieved 2008-04-27.

- Slackman, Michael (May 9, 2007). "Saudis struggle with conflict between fun and conformity". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- "Saudi Arabia". United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Retrieved 19 July 2010.

- Saeed, Abdullah; Saeed, Hassan (2004). Freedom of religion, apostasy and Islam. Ashgate Publishing. p. 227. ISBN 0-7546-3083-8.

- Adam Withnall (1 April 2014). "Saudi Arabia declares all atheists are terrorists in new law to crack down on political dissidents - Middle East - World". The Independent. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-07-10. Retrieved 2012-08-02.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Lankan mission slams false report on jailed maid". Arab News. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- "Saudi, Lankan Officials Dismiss HRW Report on Maid Abuse". Arab News. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- "Riyadh Journal; An Ambassador's Journey From Rome to Mecca". The New York Times. 4 December 2001. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- "Consular Information Sheet – Saudi Arabia". U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on 2011-11-07. Retrieved 2011-11-02.

- Cordesman, Anthony H. (2003). Saudi Arabia enters the 21st century. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 297. ISBN 0-275-98091-X.

- "Saudi religious police accused of beating pilgrims". Middle east Online. August 7, 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2007-08-21.

- "USCIRF Releases 2019 Annual Report and Recommendations for World's Most Egregious Violators of Religious Freedom". USCIRF. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- "ANNUAL REPORTOF THE U.S. COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM" (PDF). USCIRF. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- "Saudi Arabia: 2 Years Behind Bars on Apostasy Accusation". Human Rights Watch. May 15, 2014. Retrieved March 1, 2015.

- "Saudi Arabia: International Religious Freedom Report 2007". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- "Saudi Arabia" (PDF). United States Commission on International Religious Freedom. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- "Persecution of Ahmadis in Saudi Arabia". Persecution.org. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- Daurius Figueira. Jihad in Trinidad and Tobago, July 27, 1990. p. 47.

- Gerhard Böwering, Patricia Crone. The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought. p. 25-26.

- Maria Grazia Martino. The State as an Actor in Religion Policy: Policy Cycle and Governance. Retrieved March 1, 2015.

- Ali Eteraz (17 September 2007). "Supporting Islam's apostates". the Guardian. London. Retrieved 2015-03-17.

- Mortimer, Jasper (27 March 2006). "Conversion Prosecutions Rare to Muslims". Washington Post (AP).

- Marije van Beek (8 August 2015). "Saudi-Arabië: de hel voor afvalligen". Trouw (in Dutch). Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- "Saudi Arabia – An upsurge in public executions". Amnesty Intarnational. Retrieved 2011-11-02.

On 3 September 1992 Sadiq 'Abdul-Karim Malallah was publicly beheaded in al-Qatif in Saudi Arabia's Eastern Province after being convicted of apostasy and blasphemy.

- 3/25/2010: Saudi Arabia: Release Hadi Al-Mutif, March 25, 2010, United States Commission on International Religious Freedom.

- Freedom of Apostasy : The Victims.

- "Saudi Arabian columnist under threat for Twitter posts". Committee to protect journalists. 2012-02-09. Archived from the original on 2012-02-12. Retrieved 2012-02-10.

- Moumi, Habib (2012-02-09). "Mystery about controversial Saudi columnist's location deepens". Gulf News. Archived from the original on 2012-02-10. Retrieved 2012-02-10.

- "Sacrilegious Saudi writer arrested in Malaysia". Emirates 24/7. 2012-02-09. Archived from the original on 2012-02-11. Retrieved 2012-02-10.

- "Saudi Writer Hamza Kashgari Detained in Malaysia Over Muhammad Tweets". The Daily Beast. 2012-02-10. Archived from the original on 2012-02-10. Retrieved 2012-02-10.

- Hopkins, Curt (2012-02-10). "Malaysia may repatriate Saudi who faces death penalty for tweets". Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 2012-02-11. Retrieved 2012-02-10.

- McKernan, Bethan (27 April 2017). "Man 'sentenced to death for atheism' in Saudi Arabia". The Independent. Beirut. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- Rahaf Mohammed رهف محمد [@rahaf84427714] (6 January 2019). "based on the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol, I'm rahaf mohmed, formally seeking a refugee status to any country that would protect me from getting harmed or killed due to leaving my religion and torture from my family" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- Fullerton, Jamie; Davidson, Helen (21 January 2019). "'He wants to kill her': friend confirms fears of Saudi woman held in Bangkok". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2019-01-09. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- "Rahaf al-Qunun: Saudi teen granted asylum in Canada". BBC News. 11 January 2019. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- Miethe, Terance D.; Lu, Hong (2004). Punishment: a comparative historical perspective. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-521-60516-8.

- BBC News, "Pleas for condemned Saudi 'witch'", 14 February 2008 BBC NEWS, Pleas for condemned Saudi 'witch', by Heba Saleh, 14 February 2008.

- Usher, Sebastian (2010-04-01). "Death 'looms for Saudi sorcerer'". BBC News.

- "Saudi Arabia's 'Anti-Witchcraft Unit' breaks another spell". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. Retrieved 2015-09-14.

- Congressional Human Rights Caucus (2002).

- Taheri (2003).

- United States Department of State. Saudi Arabia, Country Reports on Human Rights Practices – 2004, February 28, 2005.

- Alan M. Dershowitz, Treatment of Israel strikes an alien note, Jewish World Review, 8 November 2002.

- To express the policy of the United States to ensure the divestiture... 109th CONGRESS, 1st Session, H. R. 4543.

- Religious Apartheid in Saudi Arabia, Freedom House website. Retrieved July 11, 2006.

- Michael Freund (August 9, 2007). "Saudis might take Bibles from tourists". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 2010-09-14.

- "Saudi Arabian Government Confiscates Non-Islamic Religious Items That Enter Country". Fox News. August 9, 2007. Archived from the original on 2010-12-01. Retrieved 2010-09-14.

- "International Religious Freedom Report 2007: Saudi Arabia". U.S. State Department. 2007. Retrieved 2012-08-03.

- Archived September 27, 2006, at the Wayback Machine Report by Center for Religious Freedom of Freedom House, 2006. (archived from the original on 2006-09-27)

- Waines (2003) "An Introduction to Islam" Cambridge University Press. p. 53

- "Two men arrested for "forced conversion" of a young woman: they gave her religious books". NewsXS. July 27, 2012.

External links

- Religious Freedom and the Middle East at The Washington Institute for Near East Policy PolicyWatch

- Does Saudi Arabia Preach Intolerance in the West?

- Center for Democracy and Human Rights in Saudi Arabia