History of Albany, New York

The history of Albany, New York, begins with the first interaction of Europeans with the native Indian tribes who had long inhabited the area. The area was originally inhabited by an Algonquian Indian tribe, the Mohican, as well as the Iroquois, five nations of whom the easternmost, the Mohawk, had the closest relations with traders and settlers in Albany.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Albany, New York |

|

|

|

|

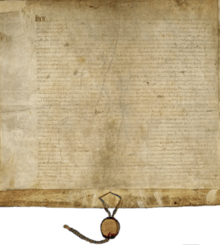

Henry Hudson first claimed this area for the Dutch in 1609. Fur traders established the first European settlement in 1614; Albany was officially chartered as a city in 1686. It succeeded Poughkeepsie as the capital of New York in 1797. It is one of the oldest surviving settlements from the original thirteen colonies, and the longest continuously chartered city in the United States. Modern Albany was founded as the Dutch trading posts of Fort Nassau in 1614 and Fort Orange in 1624; the fur trade brought in a population that settled around Fort Orange and founded a village called Beverwijck. The English took over and renamed the town Albany in 1664, in honor of the then Duke of Albany, the future James II of England and James VII of Scotland. The city was officially chartered in 1686 with the issuance of the Dongan Charter, the oldest effective city charter in the nation and possibly the longest-running instrument of municipal government in the Western Hemisphere.[1]

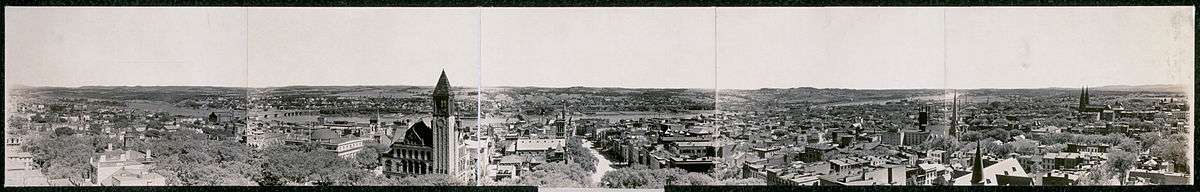

During the late 18th century and throughout of the 19th century, Albany was a center of transportation. It is located on the north end of the navigable Hudson River, was the original eastern terminus of the Erie Canal, and was home to some of the earliest railroad systems in the world. Albany's main exports at the time were beer, lumber, published works, and ironworks. Beginning in 1810, Albany was one of the ten most populous cities in the nation, a distinction that it held until the 1860 census. In the 20th century, the city opened one of the first commercial airports in the world, the precursor of today's Albany International Airport. The 1920s saw the rise of a powerful political machine controlled by the Democratic Party. The city's skyline changed in the 1960s with the construction of the Empire State Plaza and the uptown campus of SUNY Albany,[Note 1] mainly under the direction of Governor Nelson Rockefeller. While Albany experienced a decline in its population due to urban sprawl, many of its historic neighborhoods were saved from destruction through the policies of Mayor Erastus Corning 2nd, the longest-serving mayor of any city in the United States. More recently, the city has experienced growth in the high-tech industry, with great strides in the nanotechnology sector.

Albany has been a center of higher education for over a century, with much of the remainder of its economy dependent on state government and health care services. The city has experienced a rebound from the urban decline of the 1970s and 1980s, with noticeable development happening in the city's downtown and midtown neighborhoods. Albany is known for its extensive history, culture, architecture, and institutions of higher education. The city is home to the mother churches of two Christian dioceses as well as the oldest Christian congregation in Upstate New York. Albany has won the All-America City Award in both 1991 and 2009.[2]

Colonial times to 1800

Albany is one of the oldest surviving European settlements from the original thirteen colonies[3] and the longest continuously chartered city in the United States.[Note 2] The area was originally inhabited by Algonquian Indian tribes and was given different names by the various peoples. The Mohican called it Pempotowwuthut-Muhhcanneuw, meaning "the fireplace of the Mohican nation",[6] while the Iroquois called it Sche-negh-ta-da, or "through the pine woods," referring to their trail to the city.[7][Note 3] Albany's first European structure may have been a primitive fort on Castle Island built by French traders ca. 1540. It was destroyed by flooding soon after construction.[9]

Permanent European claims began when Englishman Henry Hudson, exploring for the Dutch East India Company on Halve Maen, reached the area in 1609, claiming it for the United Netherlands.[10] In 1614, Hendrick Christiaensen rebuilt the French fort as Fort Nassau, the first Dutch fur trading post in present-day Albany.[11] Commencement of the fur trade provoked hostility from the French colony in Canada and among the natives, all of whom vied to control the trade. In 1618, a flood ruined the fort on Castle Island, but it was rebuilt in 1624 as Fort Orange.[12] Both forts were named in honor of the royal Dutch House of Orange-Nassau.[13] Fort Orange and the surrounding area were incorporated as the village of Beverwijck (English: Beaver District) in 1652.[14][15]

Over the next several decades, the Mohawk, Mohican and Dutch formed a different relationship "based on a sense of mutual opportunity, of seeing more advantage in cooperation than in conflict."[16] They created a collaborative venture in the fur trade, in which each party gained something, and a measure of stability for the area. As an indicator of that, Beverwijck was never attacked by the Mohican or Mohawk, although it was in an isolated area. Like French traders before them, the Dutch often married or had unions with Mohawk and Mahican women; their descendants later intermarried with English settlers as well, leading to the area's cultural history being expressed in complex bloodlines. Many of the mixed-race children born to native women identified as Mohawk or Mahican; as these tribes had matrilineal kinship systems, the children were considered born into the mother's clan and derived all status and inheritance from her line. Some also achieved standing in the Dutch communities, becoming important interpreters and negotiators among the differing cultures.

When New Netherland was captured by the English in 1664, they changed the name Beverwijck to Albany, in honor of the Duke of Albany (later James II of England and James VII of Scotland).[17][Note 4] Duke of Albany was a Scottish title given since 1398, generally to the second son of the King of Scots.[18] The name is ultimately derived from Alba, the Gaelic name for Scotland.[19]

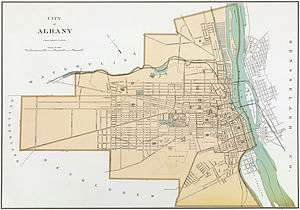

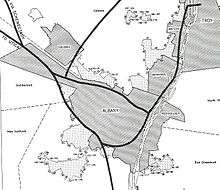

The Dutch briefly regained Albany in August 1673 and renamed the city Willemstadt; the English took permanent possession with the Treaty of Westminster (1674).[20] On November 1, 1683, the Province of New York was split into counties, with Albany County being the largest. At that time the county included all of present New York State north of Dutchess and Ulster Counties in addition to present-day Bennington County, Vermont, theoretically stretching west to the Pacific Ocean;[21][22] the city of Albany became the county seat.[23] Albany was formally chartered as a municipality by provincial Governor Thomas Dongan on July 22, 1686. The Dongan Charter was virtually identical in content to the charter awarded to the city of New York three months earlier.[24] Dongan created Albany as a strip of land 1 mile (1.6 km) wide and 16 miles (26 km) long.[25] Over the years Albany would lose much of the land to the west and annex land to the north and south. At this point, Albany had a population of about 500 people.[26]

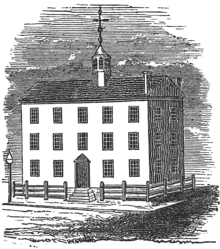

In 1754, representatives of seven British North American colonies met in the Stadt Huys, Albany's city hall, for the Albany Congress; Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania presented the Albany Plan of Union there, which was the first formal proposal to unite the colonies.[27] Although it was never adopted by Parliament, it was an important precursor to the United States Constitution.[28][Note 5] The same year, the French and Indian War began; it was the North American front of the Seven Years' War in Europe and the fourth in a series of North American wars between the colonial powers dating back to 1689, began. It ended in 1763 with French defeat by the British, resolving a situation that had been a constant threat to Albany and held back its growth.[29] In 1775, with the colonies in the midst of the Revolutionary War, the Stadt Huys became home to the Albany Committee of Correspondence (the political arm of the local revolutionary movement), which took over operation of Albany's government and eventually expanded its power to control all of Albany County. Tories and prisoners of war were often jailed in the Stadt Huys alongside common criminals.[30] In 1776, Albany native Philip Livingston signed the Declaration of Independence at Independence Hall in Philadelphia.[31]

During and after the Revolutionary War, there was a great increase in real estate transactions in Albany County. After Horatio Gates' win over John Burgoyne at Saratoga in 1777, the upper Hudson Valley was generally at peace as the war raged on elsewhere. Upstate New York began to prosper as migrants from Vermont and Connecticut began flowing in, noting the advantages of living on the Hudson and trading at Albany, while being only a few days' sail from New York City.[32] Albany reported a population of 3,498 in the first national census in 1790, an increase of almost 700% since its chartering about a century before.[26]

On November 17, 1793, a large fire broke out, destroying 26 homes on Broadway, Maiden Lane, James Street, and State Street. The fire originated at a stable belonging to Leonard Gansevoort and was suspected to be arson set by disgruntled slaves. Three slaves were arrested and charged with arson: a male slave named Pompey, owned by Matthew Visscher; a 14-year old slave girl named Dinah, owned by Volkert P. Douw; and a 12-year old slave girl named Bet, owned by Philip S. Van Rensselaer. On January 6, 1794, the three were tried and sentenced to death. For reasons unknown, Governor George Clinton issued a temporary stay of execution, but the slave girls were executed by hanging on March 14, and Pompey on April 11, 1794.[33]

In 1797, the state capital of New York was moved permanently to Albany. From statehood to this date, the Legislature had frequently moved the state capital between the city of New York, Kingston, Hurley, Poughkeepsie and Albany.[34] Albany is the second oldest state capital in the United States.[35] (The oldest is Annapolis, Maryland.)

As the state capital, Albany drew many visitors in the 1780s. As historian John Bach McMaster has explained, they did not enjoy their visit:

- Travellers of every rank complained bitterly of the inhospitality of the Albanians, and the avarice and close-fistedness of the merchants. [The environment had not] modified one jot the cold, taciturn, stingy Dutchman. They admitted that Albany was a place where a man with a modest competence could, in time, acquire riches; where a man with money could, in a short space of time, amass a fortune. But nobody would ever go to Albany who could by any possibility stay away, nor, being there, would tarry one moment longer than necessary."[36]

1800 to 1942

Albany has been a center of transportation for much of its history. In the late 18th century and early 19th century, Albany saw development of the turnpike and by 1815, Albany was the turnpike center of the state. The development of Simeon De Witt's gridded block system in 1794, which gave Albany its original bird and mammal street names,[Note 6] was intersected by these important arterials coming out of Albany, cutting through the city at unexpected angles.[39][40] The advent of the turnpike, in conjunction with canal and railroad systems, made Albany the hub of transportation for pioneers going to Buffalo and the Michigan Territory in the early and mid-19th century.[39][41]

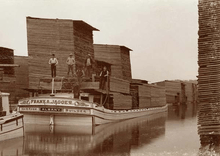

In 1807, Robert Fulton initiated a steamboat line from New York City to Albany, the first successful enterprise of its kind.[42] By 1810, with 10,763 people, Albany was the 10th largest urban place in the nation.[43] The town and village known as "the Colonie"[Note 7] to the north of Albany was annexed in 1815.[44] In 1825 the Erie Canal was completed between Albany and Lake Erie. By connecting the Hudson River to the Great Lakes, it formed a continuous water route from the Midwest to New York City, enabling the shipment of lumber and other resource commodities through the Great Lakes and to New York, strengthening trade and business at both ends, as well as along the canal. Unlike the current Barge Canal, which ends at nearby Waterford, the original Erie Canal ended at Albany; Lock 1 was located north of Colonie Street.[46] The Canal emptied into a 32-acre (13 ha) man-made lagoon called the Albany Basin, which was Albany's main port from 1825 until the Port of Albany-Rensselaer opened in 1932.[47][48]

In 1829, while working as a professor at the Albany Academy, Joseph Henry, widely regarded as "the foremost American scientist of the 19th century",[49] built the first electric motor. Three years later, he discovered electromagnetic self-induction (the SI unit for which is now the henry). He was appointed as the first Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, which supported a variety of scientific, ethnographic and historic research.[50] In the 1830 and 1840 censuses, Albany moved up to 9th largest urban place in the nation,[51][52] then back to 10th in 1850.[53] This was the last time the city ranked as one of the top ten largest urban places in the nation.[54]

Albany also has significant history with rail transport,[55] as the location of two major regional railroad headquarters. The Delaware and Hudson Railway was headquartered in Albany at what is now used as the SUNY System Administration Building.[56] In 1853, Erastus Corning, a noted industrialist and Albany's mayor from 1834 to 1837, consolidated ten railroads stretching from Albany to Buffalo into the New York Central Railroad (NYCRR). It was headquartered in Albany until Cornelius Vanderbilt moved it to New York City in 1867.[57][58] One of the ten companies that formed the NYCRR was the Mohawk and Hudson Railroad, which was the first railroad in the state and the first successful steam railroad running regularly scheduled service in the country.[59][60]

While the key to Albany's economic prosperity in the 19th century was transportation, industry and business also played a role. Dutch and German immigrants had established a thriving beer industry, and much was exported to other markets. Beverwyck Brewery, originally known as Quinn and Nolan (Nolan being mayor of Albany 1878–1883),[62] operated from that period to 1972, when it was the last remaining brewer from that time. The city's location at the east end of the Erie Canal gave it unparalleled access to both raw products and a captive customer base in the west.[63] Albany was known for its publishing houses, and to some extent, still is. Albany was second only to Boston in the number of books produced for most of the 19th century.[64] Jobs in the iron foundries in both the north and south ends of the city attracted thousands of immigrants to the city. Intricate wrought-iron details still enhance many historic buildings in Albany. The iron industry waned by the 1890s, falling victim to the costs associated with a newly unionized workforce and competition from the opening of mines in the Mesabi Range in Minnesota.[65]

Albany's other major exports during the 18th and 19th centuries were furs, wheat, meat and lumber;[66] by 1865, there were almost 4,000 saw mills in the Albany area[66] and the Albany Lumber District was the largest lumber market in the nation.[61] Later in the century, much lumber was harvested and processed in the Midwest, particularly Detroit and Chicago.

The city was also home to a number of banks. The Bank of Albany (1792–1861) was the second chartered bank in the state of New York.[67] The city was the original home of the Albank (founded in 1820 as the Albany Savings Bank),[68] KeyBank (founded in 1825 as the Commercial Bank of Albany),[69] and Norstar Bank (founded as the State Bank of Albany in 1803).[70] American Express was founded in Albany in 1850 as an express mail business.[71] In 1871, the northwestern portion of Albany—west from Magazine Street—was annexed to the neighboring town of Guilderland[72] after the town of Watervliet refused annexation of said territory.[73][74] In return for this loss, portions of Bethlehem and Watervliet were added to Albany. Part of the land annexed to Guilderland was ceded back to Albany in 1910, setting up the current western border.[75]

In 1908 Albany opened one of the first commercial airports in the world, and the first municipal airport in the United States. Originally located on a polo field on Loudon Road, it moved to Westerlo Island in 1909 and operated there until 1928. The Albany Municipal Airport—jointly owned by the city and county—was moved to its current location in Colonie in 1928. In 1960, the mayor sold the city's stake in the airport to the county, citing budget issues. It was known from then on as Albany County Airport until a massive upgrade and modernization project between 1996 and 1998, when it was rechristened Albany International Airport.[76] By 1916 Albany's northern and southern borders reached their modern courses;[75] Westerlo Island, to the south, became the second-to-last annexation, which occurred in 1926.[77]

African American migrants started arriving during World War I during the Great Migration. Another wave arrived during and after World War II. They found crowded living conditions and limited employment opportunities, but also higher wages and better schools and social services. Local organizations such as the Albany Inter-Racial Council and churches, helped them, but de facto segregation and discrimination remained well into the late 20th century.[78][79]

Corning administration (1942) to present day

Erastus Corning 2nd, arguably Albany's most notable mayor (and great-grandson of the former mayor of the same name), was elected in 1941.[80] Although he was the longest-serving mayor of any city in United States history (1942 until his death in 1983), one historian describes Corning's tenure as "long on years, short on accomplishments."[81] Grondahl said that Corning preferred to maintain the status quo, which held back potential progress during his tenure.[82] While Corning brought stability to the office of mayor, even his admirers cannot come up with a sizable list of "major concrete Corning achievements."[83] Because there was limited new development in this period, much of Albany's historic architecture survived and has been newly appreciated since the late 20th century.[Note 8]

During the 1950s and 1960s, a time when federal aid for urban renewal was plentiful,[82] Albany did not see much progress in either commerce or infrastructure. It lost more than 20 percent of its population during the Corning years, and most of the downtown businesses moved to the suburbs, following residents who had gone to newer housing.[84] While many cities across the country struggled with similar issues, the problems were magnified in Albany: interference from the Democratic political machine hindered progress considerably.[82] Governor Nelson Rockefeller (1959–1973) (R) wanted to improve the capital and state university and envisioned a monumental city; he was the driving force behind the construction of the Empire State Plaza, SUNY Albany's uptown campus, and much of the W. Averell Harriman State Office Building Campus.[85] Albany County Republican Chairman Joseph C. Frangella once quipped, "Governor Rockefeller was the best mayor Albany ever had."[86] Though opposed to the project, Mayor Corning negotiated the payment plan for the Empire State Plaza. Rockefeller did not want to be limited by the Legislature's power of the purse, so Corning devised a plan to have the county pay for the construction and have the state sign a lease-ownership agreement. The state would pay off the bonds until 2004. It was Rockefeller's only viable option, and he agreed. Due to the clout Corning gained from the situation, he gained agreement for construction of the State Museum, a convention center, and a restaurant, as part of these plans; these were projects which Rockefeller had originally vetoed. The county gained $35 million in fees and the city received $13 million for lost tax revenue.[87]

Another major project of the 1960s and 1970s was Interstate 787 and the South Mall Arterial, part of massive highway building across the country in this period.[Note 9] Construction began in the early 1960s. As happened in other places, the highway project had the adverse effect of cutting off the city from the Hudson River, which was the basis of its settlement. Corning has been called shortsighted for his failure to use the waterfront as an attraction for the city. He could have used his influence to change the location of I-787, which cuts the city off from "its whole raison d'être".[88]

Much of the original highway plan was never constructed, however: Rockefeller had wanted the South Mall Arterial to pass through the Empire State Plaza. The project would have required an underground trumpet interchange below Washington Park, connecting to the (eventually cancelled) Mid-Crosstown Arterial.[89] To this day, evidence of the original plan is still visible.[Note 10] In 1967 the hamlet of Karlsfeld became the last annexation to be added to the city limits, having come from Bethlehem.[75]

After Corning died in 1983, Thomas Whalen assumed the mayorship and was reelected twice. He gained federal dollars earmarked for restoring historic structures. What Corning had saved from destruction, Whalen refurbished.[90] In addition, the Mayor's Office of Special Events was created in an effort to increase the number of festivals and artistic events in the city, including a year-long Dongan Charter tricentennial celebration in 1986.[91] Whalen is credited for an "unparalleled cycle of commercial investment and development" in Albany due to his "aggressive business development programs".[92]

Prior to the recession of the 1990s, Albany was home to two Fortune 500 companies: KeyBank and Fleet Bank; both have since moved or merged with other banks.[93] After the death of Corning and the retirement of Congressman Sam Stratton, the political climate changed in Albany. There was more pressure on officeholders and voters regularly changed allegiances in the 1980s. Local media began following the drama surrounding county politics (specifically that of the newly created county executive position); the loss of Corning (and eventually the political machine) led to a lack of interest in city politics.[94] Gerald Jennings surprised many by his victory in the mayoral election in 1994, and his tenure since then. His tenure has essentially ended the Democratic Party political machine that had been in place since the 1920s.[95]

During the 1990s, the State Legislature approved the $234 million "Albany Plan", "a building and renovation project [that] was the most ambitious building project to effect the area since the Rockefeller era." Under the Albany Plan a number of renovation and new building projects were undertaken in the downtown area; many state workers were moved from the Harriman State Office Campus to downtown to add to its density of workers and support city life.[96] Late in the first decade of the 21st century support grew for construction of a long-discussed and controversial Albany Convention Center; as of August 2010, the Albany Convention Center Authority had already purchased 75% of the land needed to build the downtown project.[97]

Notes

- The State University of New York at Albany (its official name) is also known locally as the University at Albany, SUNY Albany, UAlbany (especially when talking about athletics), and simply SUNY.

- The Dongan Charter incorporated Albany three months after New York City's charter was ratified. However, the latter forfeited its charter during Leisler's Rebellion, making Albany's the oldest effective charter in the country.[4][5]

- This name would later be adopted by the city of Schenectady, settled to the west along the Mohawk River.[8]

- James Stuart (1633–1701), brother and successor of Charles II, was both the Duke of York and Duke of Albany before being crowned James II of England and James VII of Scotland in 1685. His title of Duke of York is the source of the name of the province of New York.[17]

- The Plan of Union's original intention was to unite the colonies in defense against aggressions of the French from the north; it was not an attempt to become independent of the British crown.[28]

- A rough grid pattern was established in 1764, aligning the streets with Clinton Avenue, which marked the northern border of Albany at the time. Patroon of the Manor of Rensselaerswyck, Stephen Van Rensselaer II followed the same directional system north of Clinton Avenue on his lands. But, the two systems were not related otherwise, which is why cross streets north and south of Clinton Avenue do not align. The stockade surrounding the city was taken down shortly before the Revolutionary War, allowing for expansion. De Witt, city surveyor at the time, continued the grid pattern to the west, renaming any streets that honored British Royalty for his 1794 map. Hawk Street is the only road that retained its original name; the rest were named after birds and mammals.[37][38]

- "The Colonie" made up the current area of Arbor Hill and was the more urban part of the Manor of Rensselaerswyck, which surrounded Albany.[44] It is the source of the name of the current town and village of Colonie.[45]

- Grondahl summarizes it as, "This hard-line position of isolationism on the part of the machine was a curse economically – but a strange blessing unintentionally in architectural terms. While downtown went to seed and plans for large-scale construction and improvements came to a virtual standstill in Albany without federal money, pockets of the city's historic housing stock escaped the wrecking ball."[82]

- The Empire State Plaza was originally known as the South Mall; the South Mall Arterial is the only remnant of that naming scheme.

- For example, the Plaza has four traffic tunnels, two intended for through traffic, and two for local traffic (only the outer, local traffic tunnels are in use); the Arterial ends abruptly between Jay Street and Hudson Avenue just west of South Swan Street (42°39′6.17″N 73°45′43.54″W); the east end of the Dunn Memorial Bridge ends abruptly in Rensselaer (42°38′33.33″N 73°44′44.78″W); and Henry Johnson Boulevard, which would have extended as part of the Mid-Crosstown Arterial, ends abruptly at Livingston Avenue (42°39′49.92″N 73°45′30.58″W).

References

- Fitzpatrick, Edward. 312-Year-Old Document Shapes City's Government. Times Union (Albany). 1998-06-03 [archived 2011-04-30; Retrieved 2010-05-23]:B4. Hearst Newspapers.

- National Civic League. All America City Awards: AAC Winners by State and City; 2010 [Retrieved 2010-09-06].

- Larnard, J.N. In: Donald E. Smith. The New Larned History for Ready Reference and Research. Vol. I (A-Bak). C.A. Nichols Publishing Company; 1922. p. 195.

- National Municipal League (1896), pp. 137–138

- Whish (1917), p. 5

- McEneny (2006), p. 6

- Howell and Tenney (1886, Vol. II), p. 460

- Notes on the Iroquois; Or, Contributions to American History, Antiquities, and General Ethnology. Albany, New York: Erastus H. Pease & Co; 1847. p. 345.

- Reynolds (1906), p. xxvii

- Henry Hudson. (2010). Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved June 27, 2010, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- Reynolds (1906), p. 17

- Howell and Tenney (1886, Vol. II), p. 775

- Venema (2003), p. 13

- Rittner (2002), p. 7

- Venema (2003), p. 12

- James Wesley Bradley, Before Albany: An Archaeology of Native-Dutch Relations in the Capital Region 1660-1664 Archived 2012-04-10 at the Library of Congress Web Archives, Albany: University of the State of New York, 2007, pp. 2-6

- Brodhead (1874), p. 744

- Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition (Albany, Dukes of). Encyclopædia Britannica Company; 1910. OCLC 197297659. p. 487.

- In: E.G. Cody. The Historie of Scotland. Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons; 1888. OCLC 3217086. p. 354.

- Reynolds (1906), p. 72

- Thorne, Kathryn Ford, Compiler & Long, John H., Editor: New York Atlas of Historical County Boundaries; The Newbury Library; 1993.

- A Map of the Provinces of New-York and New-Jersey, with a Part of Pennsylvania and the Province of Quebec (Map). ca. 1:1,040,000. Cartography by Claude Joseph Sauthier. Matthew Albert Lotter. 1777.

- French (1860), p. 155

- New York State Museum. The Dongan Charter [Retrieved 2008-11-23].

- Reynolds (1906), pp. 84–85

- New York State Museum. How a City Worked: Occupations in Colonial Albany [archived 2009-02-05; Retrieved 2009-01-10].

- Rittner (2002), p. 22

- McEneny (2006), p. 12

- McEneny (2006), p. 56

- New York State Museum. The Committee of Correspondence; 2010-03-08 [Retrieved 2010-08-19].

- United States Congress. Livingston, Philip (1716–1778) [Retrieved 2009-10-09].

- Anderson (1897), p. 68

- Gerlach, Don R. (1977). "Black Arson in Albany, New York: November 1793". Journal of Black Studies. 7 (3): 301–312. doi:10.1177/002193477700700304. JSTOR 2783709.

- The Magazine of American History with Notes and Queries. Historical Publication Co; 1886. p. 24.

- Rittner (2002), back cover

- John Bach McMaster, A History of the People of the United States, from the Revolution to the Civil War (1883) Vol. 1 pp 58-59

- Waite (1993), p. 185

- McEneny (2006), p. 68

- McEneny (2006), p. 75

- Waite (1993), p. 201

- Albany. (2010). Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved June 27, 2010, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- McEneny (2006), p. 92

- U.S. Bureau of the Census. Population of the 46 Urban Places: 1810; 1998-06-15 [Retrieved 2010-07-14].

- City of Albany Department of Urban Redevelopment. Appendix: Annexations 1815–1967 [archived 2008-08-23; Retrieved 2010-09-11].

- Town of Colonie. Colonie History: Frequently Asked Questions; 2008-06-19 [archived 2010-09-23; Retrieved 2010-09-11].

- Andrews, Horace (1895). City of Albany (Map). 1 inch per 1000 feet. Julius Bien & Company.

- The People's Welfare: Law and Regulation in Nineteenth-Century America. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press; 1996. ISBN 0-8078-4611-2. p. 139.

- New York State Historical Association. New York: A Guide to the Empire State. New York City: Oxford University Press; 1940. OCLC 504264143. p. 727.

- Joseph Henry [archived 2006-12-09; Retrieved 2010-09-18].

- Joseph Henry. (2010). Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved September 18, 2010, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- Gibson, Campbell. U.S. Bureau of the Census. Population of the 90 Urban Places: 1830; 1998-06-15 [Retrieved 2010-07-14].

- Gibson, Campbell. U.S. Bureau of the Census. Population of the 100 Urban Places: 1840; 1998-06-15 [Retrieved 2010-07-14].

- Gibson, Campbell. U.S. Bureau of the Census. Population of the 100 Urban Places: 1850; 1998-06-15 [Retrieved 2010-07-14].

- Gibson, Campbell. U.S. Bureau of the Census. Population of the 100 Largest Cities and Other Urban Places in the United States: 1790 to 1990; 1998-06-15 [Retrieved 2010-07-14].

- Pennsylvania RR Chronology; 2005 [Retrieved 2010-06-02]; p. 5.

- Waite (1993), p. 245

- The Railroad Builders, A Chronicle of the Welding of the States. Yale University Press; 1921. p. 27.

- Anderson, Eric. For a glimpse of the future, backtrack. Times Union (Albany). 2010-06-17 [archived 2011-04-30; Retrieved 2010-06-17]. Hearst Newspapers.

- New York State Department of Transportation. History of Railroads in New York State [Retrieved 2010-06-04].

- Shaughnessy, Jim (1997) [1982]. Delaware & Hudson. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. p. 89. ISBN 0-8156-0455-6. OCLC 36008594.

- The Albany Lumber Trade: Its History and Extent. Albany: The Argus Company; 1872. OCLC 8260640. p. 7.

- United States Congress. Nolan, Michael Nicholas [Retrieved 2010-06-30].

- McEneny (2006), pp. 87–88

- McEneny (2006), p. 88

- McEneny (2006), pp. 88 & 92

- McEneny (2006), p. 65

- New York State Museum. The Bank of Albany; 2008-01-06 [Retrieved 2010-07-19].

- No author listed. Trust(Co) Worth Advice?. Times Union (Albany). 2007-06-10 [archived 2011-04-30; Retrieved 2010-07-19]:C1. Hearst Newspapers.

- No author listed. KeyCorp. Times Union (Albany). 2008-11-10 [archived 2011-04-30; Retrieved 2010-07-19]:C8. Hearst Newspapers.

- Gordon, Marcy. Bank Merger Clears Last Hurdle. Times Union (Albany). 2004-03-09 [archived 2011-04-30; Retrieved 2010-07-19]:E1. Hearst Newspapers.

- Reynolds (1906), p. 603

- Howell and Tenny (1886, Vol. I), p. 77

- Laws of the State of New York, Passed at the Ninety-Third Session of the Legislature, Begun January Fourth, and Ended April Twenty-Sixth, 1870, in the City of Albany. Volume I. State of New York/Weed, Parsons and Company; 1870 [Retrieved 2010-09-11]. p. 412.

- Laws of the State of New York, Passed at the Ninety-Fourth Session of the Legislature, Begun January Third, and Ended April Twenty-first 1871, in the City of Albany. Volume II. State of New York/The Argus Company; 1871 [Retrieved 2010-09-11]. p. 1688.

- Albany County, New York. Appendix [archived 2008-08-23; Retrieved 2010-09-11].

- Albany International Airport. Albany Airport History [archived 2008-12-22; Retrieved 2010-06-02].

- Town of Bethlehem. Cutting Ice: Big Business in Bethlehem [archived 2010-10-06; Retrieved 2010-09-11].

- Jennifer A. Lemak, "Albany, New York and the Great Migration." Afro-Americans in New York Life and History 32.1 (2008): 47-74.

- Jennifer A. Lemak, Southern Life, Northern City: The History of Albany's Rapp Road Community (SUNY Press, 2008).

- McEneny (2006), p. 157

- Grondahl (2007), p. 490

- Grondahl (2007), p. 500

- Grondahl (2007), p. 494

- Grondahl (2007), p. 492

- Grondahl (2007), p. 501

- Grondahl (2007), p. 502

- Grondahl (2007), pp. 467–469

- Grondahl (2007), p. 498

- Jordan, Christopher. Capital Highways. Mid-Crosstown Arterial; 2006 [archived 2011-04-29; Retrieved 2010-06-28].

- McEneny (2006), p. 191

- McEneny (2006), p. 192

- Pace, Eric. Thomas M. Whalen III, 68, Three-Term Mayor of Albany (Obituary). 2002-03-08 [Retrieved 2010-07-18]. The New York Times.

- McEneny (2006), p. 193

- McEneny (2006), pp. 193–194

- McEneny (2006), p. 198

- McEneny (2006), p. 201

- Carleo-Evangelist, Jordan. Convention center pieces fall into place. Times Union (Albany). 2010-08-27 [Retrieved 2010-08-29]. Hearst Newspapers.

Bibliography

- Albany Directory. Albany: Adams, Sampson & Co. 1858, 1859, 1860, 1869(Full text via the Internet Archive.)

- Anderson, George Baker. Landmarks of Rensselaer County New York. Syracuse, New York: D. Mason and Company; 1897. OCLC 1728151.(Full text via the Internet Archive.)

- "Albany", Appleton's Illustrated Hand-Book of American Cities, New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1876(Full text via the Internet Archive.)

- Becker, Martin Joseph. A history of Catholic life in the diocese of Albany, 1609-1864 (1975)

- Brodhead, John Romeyn. History of the State of New York. New York City: Harper & Brothers, Publishers; 1874. OCLC 458890237.(Full text via Google Books.)

- Burger, Joanna. Whispers in the Pines: a Naturalist in the Northeast. Piscataway, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press; 2006. ISBN 0-8135-3794-0.

- French, John Homer. Historical and Statistical Gazetteer of New York State. Syracuse, New York: R. Pearsall Smith; 1860. OCLC 224691273.(Full text via Google Books.)

- Greenberg, Brian. Worker and Community: Response to Industrialization in a Nineteenth Century American City, Albany, New York, 1850-1884 (SUNY Press, 1980)

- Grondahl, Paul. Mayor Erastus Corning: Albany Icon, Albany Enigma. Albany: State University of New York Press; 2007. ISBN 978-0-7914-7294-1.

- Hackett, David G. The Rude Hand of Innovation: Religion and Social Order in Albany, New York, 1652-1836 (Oxford University Press, 1991)

- Howell, George Rogers. Bi-centennial History of Albany: History of the County of Albany, N.Y. from 1609 to 1886 (Volume I). Jonathan Tenney. New York City: W. W. Munsell & Co; 1886. OCLC 11543538.(Full text via Google Books.)

- Howell, George Rogers. Bi-centennial History of Albany: History of the County of Albany, N.Y. from 1609 to 1886 (Volume II). Jonathan Tenney. New York City: W. W. Munsell & Co; 1886. OCLC 11543538.(Full text via Google Books.)

- Kenney, Alice P. "Dutch Patricians in Colonial Albany." New York History (1968) 49: 249–283.

- Kenney, Alice P. "The Transformation of the Albany Patricians, 1778–1860," New York History (1987) 68#2 pp. 151–173 in JSTOR

- Kenney, Alice P. The Gansevoorts of Albany: Dutch Patricians in the Upper Hudson Valley (Syracuse Univ Press, 1969)

- McEneny, John. Albany, Capital City on the Hudson: An Illustrated History. Sun Valley, California: American Historical Press; 2006. ISBN 1-892724-53-7.

- Munsell's Albany Directory. Albany: J. Munsell. 1853. hdl:2027/umn.31951002233730d.(Full text via HathiTrust Digital Library.)

- National Municipal League. Proceedings of the Conference for Good City Government and the Annual Meeting of the National Municipal League (Volume 5). Philadelphia: Selheimer Printing Company; 1896. OCLC 40371852. p. 137–148.(Full text via Google Books.)

- Reynolds, Cuyler. Albany Chronicles: A History of the City Arranged Chronologically, From the Earliest Settlement to the Present Time. Albany: J. B. Lyon Company; 1906. OCLC 457804870.(Full text via Google Books.)

- Rittner, Don. Then & Now: Albany. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing; 2002. ISBN 0-7385-1142-0.

- Rittner, Don. Remembering Albany: Heritage on the Hudson. Charleston, South Carolina: History Press; 2009. ISBN 978-1-59629-770-8.

- Roberts, Warren. A Place in History: Albany in the Age of Revolution, 1775-1825. Albany, NY: SUNY Press; 2010. ISBN 978-1-4384-3329-5.

- Venema, Janny. Beverwijck: A Dutch Village on the American Frontier, 1652–1664. Hilversum: Verloren; 2003. ISBN 0-7914-6079-7.

- Waite, Diana S. Albany Architecture: A Guide to the City. Albany: Mount Ida Press; 1993. ISBN 0-9625368-1-4.

- Whish, John D. Albany Guide Book. Albany: J.B. Lyon Company; 1917. OCLC 17438709.(Full text via Google Books.)