Mesabi Range

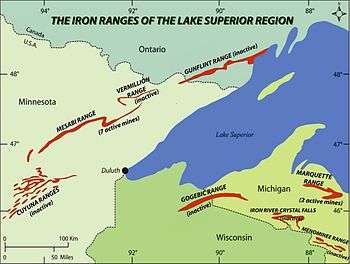

The Mesabi Iron Range is a mining district in northeastern Minnesota following an elongate trend containing large deposits of iron ore. It is the largest of four major iron ranges in the region collectively known as the Iron Range of Minnesota. First described in 1866, it is the chief iron ore mining district in the United States. The district is located largely in Itasca and Saint Louis counties. It has been extensively worked since 1892, and has seen a transition from high-grade direct shipping ores, to gravity concentrates, to the current industry producing exclusively iron ore (taconite) pellets. Production has been dominantly controlled by vertically integrated steelmakers since 1901, and therefore is dictated largely by US ironmaking capacity and demand.

Name

The Mesabi Range was known to the local Ojibwe as Misaabe-wajiw ("Giant mountain").[1][2] Throughout the Mesabi Range, "Mesaba" and "Missabe" spelling variations are found along with places containing "Giant" in their names.

Geology

There are three iron ranges in northern Minnesota, the Cuyuna, the Vermilion, and the Mesabi. Most of the world's iron ore, including that contained in northern Minnesota, was formed during the middle Precambrian. During this period, erosion leveled mountains. This erosion released iron and silica into the waters of a new sea. Marine algae living in this new sea raised the level of atmospheric oxygen. This oxygen catastrophe caused the eroded iron to precipitate into the banded iron formations found in northern Minnesota and other members of the Animikie Group. Over billions of years, geological forces left behind ore deposits of varied quality and concentrations – differences that would determine how the ore was mined from place to place. On the Mesabi Range, stretching 100 miles (160 km) from Grand Rapids to Babbitt, soft ore lay close to the surface, where it could be scooped from open pit mines.[3]

The overall structure of the range is that of a monocline dipping 5 to 15 degrees to the southeast. Key faults include the Calumet, La Rue, Morton, Biwabik, and the Siphon. The Duluth Gabbro complex to the east has caused metamorphic changes in the Biwabik formation. The natural iron ores and the magnetite taconites occur in this Precambrian Biwabik formation, which is a cherty layer 340–750 feet (100–230 m) thick. The natural ores are located in elongated channels or tabular deposits, while the magnetite taconites occur in stratigraphic zones. Natural ores have an iron content of 51 to 57 per cent while the pellets contain 60 to 67 per cent. The natural ores are mainly mixtures of hematite and goethite.[4]:519–520, 522, 527–528 The most common silicate is Minnesotaite. Also of note are the presence of algal structures in the Biwabik formation.[5]

Physical extent

The Mesabi Range is 110 miles (180 km) long. Heights vary from 200–500 feet (61–152 m). The highest point, located about 5.6 miles (9.0 km) northeast of Virginia, is Pike Mountain at 1,950 feet (590 m).[6] The range trends from the northeast to the southwest, extending from Babbitt to Grand Rapids.[7]

Embarrass Mountains

The Embarrass Mountains are a small subrange of the Mesabi Range, spanning about 9 miles (14 km) through northern White Township and Hoyt Lakes in St. Louis County. Heights vary from 200–400 feet (61–122 m).[8] The highest point, at 1,940 feet (590 m), is roughly 1.9 miles (3.1 km) west of the unincorporated community of Hinsdale,[6] near the former Erie Mining Company's pits and taconite processing plant.

Mining operations

Iron-bearing rocks were noted by the Minnesota State Geologist Henry H. Eames in 1866. Iron ore was discovered north of Mountain Iron, Minnesota on 16 Nov. 1890 by J.A. Nichols of the Merritt brothers. The range was defined by 1900. Initially underground mines were employed but these gave way to open pits so that by 1902, half the operations were conducted this way. The last underground mine closed in 1960. Natural ores eventually gave way to iron-ore concentrates from magnetite taconite so that by 1965 one third of production came from these pellets.[4]

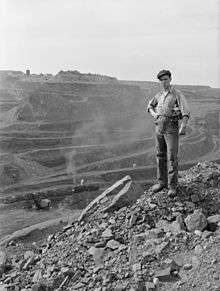

Iron ore is currently mined only from open pits, although some mines operated underground early on.[9]

Much of the softer ore was formed close to the surface, allowing mining operations to be conducted via open pit mines. The world's largest open pit iron ore mine is the Hull–Rust–Mahoning Open Pit Iron Mine in Hibbing. In the early years of mining from the late 19th century until the 1950s, mining focus was on high grade ore that could be processed into steel without much change. However, when that supply dried up, focus shifted to lower-grade ore (taconite) which requires extensive processing at large mining-processing facilities before moving to port. The mined ore is then transported, primarily by the Duluth, Missabe and Iron Range Railway, to the ports of Two Harbors and Duluth. At Duluth, trains of up to eighty 100-ton open cars are moved out on massive ore docks to be dumped into "lakers" of up to 60,000 tons weight for movement to steel mills in Indiana and Ohio.

Open pit mines that are no longer worked are a common feature along the Iron Range. Some of these sites have been redeveloped for other uses. For instance, the Virginia Pilot is a project which focuses on redeveloping the grounds adjacent to the old mines into low- to moderate-income residential space. The Hill-Annex Mine is now a state park and offers tours to visitors who wish to learn about mine operations. Tours are guided by former mine workers.

Currently, there are six mining-processing facilities in operation on the Iron Range. Cliffs Natural Resources owns and operates Northshore Mining, which has mining operations in Babbitt and crushing, concentrating (grinding) and pelletizing operations in Silver Bay, along with United Taconite which has mining operations in Eveleth and crushing, concentrating and pelletizing operations in Forbes. Arcelor Mittal owns and operates the Minorca Mine and Plant with mining operations near Biwabik and Gilbert and a crushing, concentrating and pelletizing facility near Virginia (47.5428°N 92.5169°W). United States Steel owns and operates both KeeTac (47.3992°N 93.0759°W) and Minntac (47.49730°N 92.61401°W) with mining and processing facilities in Keewatin and Mountain Iron respectively. The last facility is Hibbing Taconite which operates a mine and plant between the cities of Hibbing and Chisholm. Although Arcelor Mittal owns a majority stake in Hibbing Taconite, the operating agent is actually a minority owner, Cliffs Natural Resources. United States Steel is also a minority stakeholder in Hibbing Taconite.

In addition, Essar Steel is building a mine/plant near Nashwauk that has plans to not only mine and process the taconite, but eventually to produce steel on-site ready for shipment around the world. Steel Dynamics and Kobe Steel own Mesabi Nugget (47.5280°N 92.1216°W) near Hoyt Lakes which does not yet mine its own material, but does produce high-iron content nuggets. Magnetation, Inc. is another company currently working the Iron Range, but their focus is reclaiming leftover iron from ore dumps with company-designed high-power magnetic separators to produce concentrate to sell and ship throughout the world.

Rockefellers' Interests

John D. Rockefeller had previously loaned money to his brother, Frank Rockefeller, and Frank's business associate, James Corrigan to buy into the Franklin Iron Mine Company, which operated in the Mesabi Range. By late 1896 or early 1897, John D. took Corrigan's shares due to failure to repay loans. Frank and Carrigan were forced to sell the company.[10] The market for ore from the Mesabi range was almost non-existent at this time because American steel furnaces were not built to deal with its powdery nature and steelmakers believed it to be poor ore. John D. invested $40 million to build up the Mesabi ore and transportation business. To reach the steelmakers in Pittsburgh, the ore had to travel across the Great Lakes to Cleveland. He invested $2 million into a railroad to transport the ore from the Mesabi range to Duluth on Lake Superior. By 1896, he controlled the Lake Superior Consolidated Iron Mines Company, which was a holding company of the Merritt brothers. He built a fleet of ore ships. In December 1896, he made a deal with Henry W. Oliver and Andrew Carnegie of Pittsburgh whereby they agreed not to go into the ore field or transportation business, and John D. agreed not to go into the steel business. The steelmakers adapted their mills to process the ore from the Mesabi range. Oliver broke with the agreement, and in response, John D. procured a monopoly of ore ship transportation on the Great Lakes. John D. sold his western ore holdings to J.P. Morgan for $90,900,000 soon after Morgan bought Carnegie's steel interests in 1901.[11][12]

Labor strikes

Several large-scale strikes took place on the Mesabi Iron Range during the early 1900s. The first began on July 20, 1907 after the Western Federation of Miners (WFM) asked Oliver Iron Mining Company for, among other demands, an eight-hour work day and a pay raise. The strike lasted two months and resulted in thousands of workers being blacklisted.[13]

In June 1913, the WFM organized a strike of the copper companies in the region, again demanding shorter hours and better pay. This unsuccessful strike lasted 265 days and is known as the Copper Country Strike of 1913–1914.[14]

On June 25, 1916, a miner left his shift after being paid less than the contracted rate. His action led to the Mesabi range strike of 1916. The Industrial Workers of the World quickly supported the strike for better pay and shorter hours. In September 1916, the workers voted to resume work, assuming a failed strike. However, shortly after returning to work a 10% raise in wages was issued for workers throughout the Range.[15]

See also

References

- The Ojibwe peoples dictionary. Minnesota Geographic Names. Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society (Minnesota Historical Society: St. Paul, 1920), page 504. Available in fulltext at Google Book Search Archived May 29, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- John D. Nichols and Earl Nyholm. A Concise Dictionary of Minnesota Ojibwe. University of Minnesota Press (University of Minnesota: Minneapolis, 1995) ISBN 0-8166-2427-5

- "History of the Iron Range". Archived from the original on July 20, 2014. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

- Marsden, R.W.; Emanuelson, J.W.; Owens, J.S.; Walker, N.E.; Werner, R.F. (1968). John D. Ridge (ed.). The Mesabi Iron Range, Minnesota, in Volume 1 of Ore Deposits of the United States, 1933–1967. The American Institute of Mining, Metallurgical, and Petroleum Engineers, Inc. p. 520-521.

- Gruner, John (1946). The Mineralogy and Geology of the Taconites and Iron Ores of the Mesabi Range, Minnesota. Office of the Commissioner of the Iron Range Resources and Rehabilitation. p. 8,38.

- Mangou, Patrick J. "The Archean Terranes of Minnesota". US Geology and Geomorphology. Retrieved February 13, 2016.

- Mesabi Range Archived April 26, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- "MyTopo Free Online Topo Maps". MyTopo. Retrieved February 13, 2016.

- Iron Range – The Mining Frontier Archived September 24, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. Macalester College.

- Hawke, David Freeman (1980). John D. The Founding Father of the Rockefellers. Harper & Row. pp. 203-204. ISBN 978-0060118136.

- Hawke, David Freeman (1980). John D. The Founding Father of the Rockefellers. Harper & Row. pp. 208-211. ISBN 978-0060118136.

- Rockefeller, John (2019). Random Reminiscences of Man and Events. Compass Circle. pp. 75–86. ISBN 9781790494996.

- Michael G. Karni (1986). Dirk Hoerder (ed.). Struggle a Hard Battle. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press. pp. 210–211.

- Michael G. Karni (1986). Dirk Hoerder (ed.). Struggle a Hard Battle. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press. pp. 215–216.

- Michael G. Karni (1986). Dirk Hoerder (ed.). Struggle a Hard Battle. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press. pp. 218–219.

- Leith, Charles Kenneth (1903). The Mesabi Iron-bearing District of Minnesota. U.S. Geological Survey Monograph 43. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office.

- Stacy, Francis N. (September 1904). "The Iron Mines That Give Us Leadership: The Most Extraordinary Deposits In The World In The Mesabi Range". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. VIII: 5235–5243. Retrieved July 10, 2009. Includes numerous photos of c. 1904 Mesabi iron works.

Further reading

- Beck, J. Robert. Well, Here We Are! The Hansons and the Becks. Lincoln, Nebraska: iUniverse, 2005.—A history of a Swedish-Finnish immigrant family from the Mesabi Iron Range, which details the social (and socialist) conditions of the area during its heyday.

- George, Harrison. "The Mesaba Iron Range," International Socialist Review, vol. 17, no. 6 (December 1916), pp. 329–332.

- George, Harrison. "Victory on the Mesaba Range," International Socialist Review, vol. 17, no. 7 (January 1917), pp. 429–431.

- Hawke, David Freeman (1980). John D. The Founding Father of the Rockefellers. Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0060118136.