Manor of Rensselaerswyck

The Manor of Rensselaerswyck, Manor Rensselaerswyck, Van Rensselaer Manor, or just simply Rensselaerswyck (Dutch: Rensselaerswijck Dutch pronunciation: [ˈrɛnsəlaːrsˌʋɛik]),[lower-alpha 1] was the name of a colonial estate—specifically, a Dutch patroonship and later an English manor—owned by the van Rensselaer family that was located in what is now mainly the Capital District of New York in the United States.

Manor of Rensselaerswyck Rensselaerswijck | |

|---|---|

Seal | |

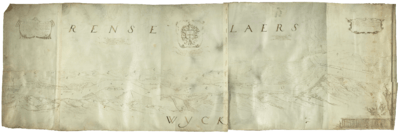

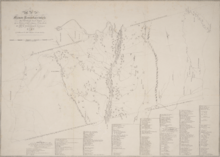

Map of Rensselaerswyck, c. 1632 | |

Manor of Rensselaerswyck Location within the state of New York | |

| Coordinates: 42°41′37″N 73°42′29″W | |

| Country | Netherlands |

| Colony | New Netherland |

| Rensselaerswyck | 1630 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Feudal patroonship, Proprietary colony |

| Population (1839) | |

| • Total | About 3,000 |

The estate was originally deeded by the Dutch West India Company in 1630 to Kiliaen van Rensselaer, a Dutch merchant and one of the company's original directors. Rensselaerswyck extended for miles on each side of the Hudson River near present-day Albany. It included most of what are now the present New York counties of Albany and Rensselaer, as well as parts of Columbia and Greene counties.

Under the terms of the patroonship, the patroon had nearly total jurisdictional authority, establishing civil and criminal law, villages, a church (in part to record vital records, which were not done by the state until the late 19th century). Tenant farmers were allowed to work on the land, but had to pay rent to the owners, and had no rights to property. In addition, the Rensselaers harvested timber from the property.

The patroonship was maintained intact by Rensselaer descendants for more than two centuries. It was split up after the death of Stephen van Rensselaer III in 1839. His son Stephen Van Rensselaer IV, the 10th and last patroon, received the bulk of his holdings; son William received some lands east of the Hudson.

At his death, Steven van Rensselaer III's land holdings made him the tenth-richest American in history to date.[1] Under his sons tenant farmers began protesting the manor system, part of a sweeping challenge in New York State. Under financial, judicial, and political pressure from this anti-rent movement Stephen IV and William sold off most of their land, ending the patroonship in the 1840s. For length of operations, it was the most successful patroonship established under the West India Company system.[2]

| New Netherland series |

|---|

| Exploration |

| Fortifications: |

|

| Settlements: |

| The Patroon System |

|

| People of New Netherland |

| Flushing Remonstrance |

|

| Rensselaerswyck series | |

|---|---|

| Dutch West India Company | |

| The Patroon System | |

| Map of Rensselaerswyck | |

| Patroons of Rensselaerswyck: Kiliaen van Rensselaer | |

|

Establishing patroonships

Upon discovery of the Albany area by Henry Hudson in 1609, the Dutch claimed the area and set up two forts to anchor it: Fort Nassau in 1614 and Fort Orange in 1624, both named for the Dutch noble House of Orange-Nassau. This established a Dutch presence in the area, formally called New Netherland. In June 1620, the Dutch West India Company was established by the States-General and given enormous powers in the New World. In the name of the States-General, it had the authority to make contracts and alliances with princes and natives, build forts, administer justice, appoint and discharge governors, soldiers, and public officers, and promote trade in New Netherland.[4]

In order to attract capitalists to the colony, the managers of the West India Company, offered certain exclusive privileges to the members of the company in 1630. The terms of the charter stated that any member who founded a colony of fifty adults in New Netherland within four years of the charter's writing would be acknowledged as a patroon of the territory to be colonized. The only restriction was that the colony had to be outside the island of Manhattan.[4]

To meet such cases, the West India Company adopted the Charter of Freedoms and Exemptions for the agricultural colonization of its American province. The chief features of this charter stated that lands for each colony could extend 16 miles (26 km) in length if confined to one side of a navigable river or 8 miles (13 km) if both sides were occupied. Additionally, the lands could extend into the countryside and even be enlarged if more immigrants were to settle there.[4]

Each patroon would have the chief command within their respective patroonship, having the sole rights to fish and hunt. If a city were to be founded within its boundaries, the patroon would have the power and authority to establish officers and magistrates. Each patroonship was free of taxes and tariffs for ten years following its founding.[4]

A contract to settle under a patroonship was enforceable: no colonists could leave the colony during their term of service without the written consent of the patroon, and the West India Company pledged itself to do everything in its power to apprehend and deliver up all fugitives from the patroon's service.[4]

Colonists of a patroonship were limited by the West India Company in some instances. For example, fur trading was illegal for colonists; it was reserved as a Company monopoly. But, patroonships had the right to trade anywhere from Newfoundland to Florida, on the understanding that traders were to stop at Manhattan to possibly trade there first.[4]

Each patroon was required to "satisfy the Indians of that place for the land", proscribing that the land must be bought (or bartered) from the local Indians, and not just taken.[5] Additionally, the Company agreed to defend all colonists, whether free or in service, from all aggressors,[6] and supply the patroonship— for free —"with as many blacks as it possibly can... for [no] longer [a] time than it shall see fit".[7]

Founding the Manor

Kiliaen van Rensselaer, a pearl and diamond merchant of Amsterdam, was one of the original directors of the West India Company[8] and one of the first to take advantage of the new settlement charter. On January 13, 1629, van Rensselaer sent notification to the Directors of the Company that he, in conjunction with fellow Company members Samuel Godyn and Samuel Blommaert, sent Gillis Houset and Jacob Jansz Cuyper to determine satisfactory locations for settlement. This took place even before the Charter of Freedoms and Exemptions was ratified, but was done in agreement with a draft of the Charter from March 28, 1628.[9] On April 8, 1630, a representative for van Rensselaer purchased a large tract of land from its American Indian owners adjacent to Fort Orange, on the west side of the Hudson River. It extended from Beeren Island north to Smack's Island and extended "two day's journey into the interior."[4]

In the meantime, van Rensselaer made vigorous preparations to send out tenants. Early in the spring, several emigrants, with their farm implements and cattle, were sent out from the Netherlands under Wolfert Gerritson, who was designated the overseer of farms. These pioneers of the manor embarked at the island of Texel in the ship Eendragt, or Unity, under Captain John Brouwer. In a few weeks, they arrived at Fort Orange and began the development and settlement of the Manor of Rensselaerswyck.[4]

A few weeks after the arrival of the first colonists, the patroon's special agent, Gillis Hassett, secured a grant of land from the Indians, lying mostly to the north of Fort Orange and extending up the river to an Indian structure called Monemins Castle. This was situated on Haver Island at the confluence of the Mohawk and Hudson rivers. This and the earlier purchase completed the bounds of the manor on the west side of the Hudson.[4]

Each tenant was required to swear an oath of loyalty to the patroon, without question. The following is the oath stated by each tenant:

I, <name>, promise and swear that I shall be true and faithful to the noble Patroon and Co-directors, or those Commissioners and Council, subjecting myself to the good and faithful inhabitant or Burgher, without exciting any opposition, tumult, or noise; but on the contrary, as a loyal inhabitant, to maintain and support offensively and of the Colonie. And with reverence and fear of the Lord, and uplifting of both the first fingers of the right hand, I say — SO TRULY HELP ME GOD ALMIGHTY.[10]

At that time, the land on the east side of the river, extending north from Castle Island to the Mohawk River was then the private property of an Indian chief named Nawanemitt. This territory was called "Semesseck" by the Indians, and described in the grant as "lying on the east side of the aforesaid river, opposite the Fort Orange, as well above as below, and from Poetanock, the millcreek, northward to Negagonee, being about twelve miles, large measure."[4]

These purchases took place on August 8, and August 13, 1630, respectively, confirmed by the council at Manhattan, and patents formally issued therefor. Fort Orange and the land immediately around its walls, still remained under the exclusive jurisdiction of the West India Company. It eventually developed as the city of Albany, which was never under the direct dominion of the patroon.[4]

But this large purchase by van Rensselaer excited the jealousy of other capitalists. He soon divided his estate around and near Fort Orange into five shares,[4] in an effort to advance more rapidly the growth of the colony.[11] Two of these shares he retained, together with the title and honors of the original patroon. One share was given to Johannes de Laet, another was given to Samuel Godyn, and the last to Samuel Bloommaert; these three men were influential members of the Amsterdam chamber of the West India Company. On the ancient map of the colony, "Bloommaert's Burt" is located at the mouth of what is now called Patroon Creek. "De Laet's Island" was the original name of van Rensselaer Island, opposite Albany. "De Laet's Burg" equates to Greenbush. "Godyn's Islands" are a short distance below, on the east shore.[4] These three separate patroonships were subsequently purchased and dissolved into Rensselaerswyck proper by 1685.[11]

Government

The government of the Manor of Rensselaerswyck was vested in a general court, which exercised executive, legislative or municipal, and judicial functions. This court was composed of two commissioners, styled "Gecommitteerden", and two councilors, called "Gerechts-persoonen", or "Schepenen". These last equated to our modern justices of the peace. There was also a colonial secretary, a "Schout-fiscaal", or sheriff, and a "Gerechts-bode", court messenger or constable.[4]

The magistrates held their offices for a year, the court appointing their successors. The most important office in the colony was the schout-fiscaal, or sheriff. Jacob Albertsen Planck was the first sheriff of Rensselaerswyck. Arent van Curler, who immigrated as assistant commissary, was soon after his arrival promoted to commissary-general, or superintendent of the colony. He also served as colonial secretary until 1642, when he was succeeded by Anthony de Hooges.[4]

Culture

The population of the colony of Rensselaerswyck in its early days consisted of three classes: freemen on top, who emigrated from Holland at their own expense; farmers next; and farm servants sent by the patroon at the bottom of the caste system.[4]

The first patroon judiciously applied his large resources to the advancement of his interests, and was quick to assist people on the estate. He initially defined several farms on both sides of the river, on which he ordered houses, barns, and stables to be erected. The patroon paid to stock these farms with cattle, horses, and sometimes with sheep, and furnished the necessary wagons, plows, and other implements. So the early farmer entered upon his land without being embarrassed by want of capital.[4]

Sustaining the Manor

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

History is almost certain that Kiliaen van Rensselaer never visited his land in New Netherland. The Van Rensselaer Bowier Manuscripts, a collection of translated primary documents from that time, state,

The present letters show beyond the possibility of doubt that Kiliaen van Rensselaer did not visit his colony in person between 1630 and 1643, and the records preserved among the Rensselaerswyck manuscripts make it equally certain that he did not do so between the last named date and his death…[15] Upon van Rensselaer's death in the 1640s,[lower-alpha 2]

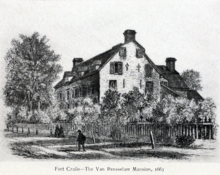

The estate was inherited by his eldest son Jan Baptist, who acquired the title of patroon. He died in 1658 and his younger brother Jeremias van Rensselaer became patroon. Acknowledging the surrender of New Amsterdam and Fort Orange to England in 1664 following a surprise incursion by the English during a time of peace (which led to the Second Anglo–Dutch War),[23] Jeremias took the oath of allegiance to the King of England that October.[24] In 1666, he also built the original Manor House, also known as Fort Crailo for its defensive reinforcement, located north of Fort Orange. The Manor House was the seat of the patroonship and the home of the patroon until 1765.[25]

.jpg)

Jeremias died in 1674 and the estate was passed on to his oldest son, Kiliaen Van Rensselaer, grandson to the first patroon, his namesake. Kiliaen was eleven when his father died. The estate was managed on his behalf, and he did not acquire the title of Lord of the Manor until he was twenty-one.[26] Maria van Cortlandt van Rensselaer, Jeremias's wife and Kiliaen's mother was the administrator and treasurer of the Manor of Rensselaerswyck until 1687.[27][28]

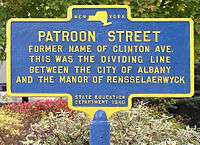

In 1683, one year before Kiliaen became Lord of the Manor, New York Governor Thomas Dongan established Albany County, one of the original twelve counties in New York. The county was to "containe the Towns of Albany, the Collony Renslaerwyck, Schonecteda, and all the villages, neighborhoods, and Christian Plantacons on the east side of Hudson River from Roelof Jansen's Creeke, and on the west side from Sawyer's Creeke to the Sarraghtoga."[29] In 1685, Governor Dongan granted a patent for Rensselaerswyck, making it a legal entity.[30] The patent included a detailed description of its boundaries, stating:

...the banks of Hudsons River... beginning att the south end... or Berrent Island on Hudsons River and extending northwards up along both sides of the said Hudsons River unto A place heretofore Called the Kahoos or the Great Falls of the said River & extending itselfe east and west all along from each side of the said river backwards into the woods twenty fouer english miles As Also A Certaine tract of land situate lyeing and being on the east side of Hudsons River beginning at the Creeke by Major Abraham States and soe Along the said River southward to the south side of Vastrix Island by a creek called Waghankasigh stretching from thence with an easterly line into the woods twenty fouer english miles to a place called Wawanaquaisick And from thence northward to the head of the said Creeke by Major Abrahams States as Aforesaid.[30]

One year later in 1686, Albany was chartered as a city under the Dongan Charter, authored by Governor Dongan.[31] During Kiliaen's tenure as patroon, he served in many political appointed positions in Albany, including assessor, justice, and supervisor, and represented Rensselaerswyck in the New York General Assembly.[26] In 1704, Kiliaen split Rensselaerswyck into two portions, the southern portion, or "Lower Manor" (comprising Greenbush and Claverack), placed under the eye of his brother Hendrick. The northern portion retained the title Rensselaerswyck.[30]

Hendrick von Rensselaer lived in Albany until a year after receiving the Lower Manor, representing Rensselaerswyck in the General Assembly[lower-alpha 3] from 1705 until 1715,[32] just as his brother had from 1693 to 1704.[26]

Kiliaen died in 1719[26] and the patroonship passed on to his oldest son Jeremias.[33] Jeremias died in 1745 and the estate passed to his brother Stephen. Stephen, sickly at the time, died two years later in 1747 at the age of forty.[33] The estate was passed on to his son, Stephen van Rensselaer II, who was five when his father died.[34] Stephen II was active in the Albany County Militia and active in restructuring loose land leases created by his predecessors. One of his land deals was made in the eastern region of Rensselaerswyck; the Town of Stephentown in southeastern Rensselaer County was named for him.[34] He also rebuilt the Manor House in 1765.[25]

Stephen II died in 1769 at the age of 27 as one of the richest men in the region.[34] The Manor passed on to his eldest son Stephen van Rensselaer III, who was five at the time of his father's death.[35] The estate was controlled by Abraham Ten Broeck until Stephen III's twenty-fifth birthday.[35] Stephen III attended school in Albany and then New Jersey and Kingston during the Revolution. He graduated from Harvard College in 1782.

Stephen van Rensselaer III became well known for his many achievements. In 1825, he was elected Grand Master of the New York State Grand Masonic Lodge. He was elected to the New York State Assembly in 1789 and was re-elected until chosen by the legislature for the New York State Senate in 1791. In 1795 he was elected Lieutenant Governor of New York. He was elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1822, serving until 1829. He was also commissioned a Lieutenant General in the New York State Militia, and led an unsuccessful invasion of Canada at Niagara in the War of 1812. His most lasting achievement was to found, with Amos Eaton, the Rensselaer School, which developed into the present-day Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.[35]

Anti-rent movement and downfall

Stephen III lived to be 75, dying in 1839. He is remembered as "The Good Patroon" and also "The Last Patroon" because he was legally the last patroon of Rensselaerswyck.[35] At the time of his death, Stephen III was worth about $10 million (about $88 billion in 2007 dollars) and is noted as being the tenth-richest American in history.[1]

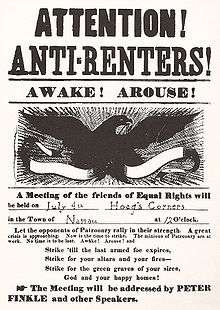

The spectacle of a landed gentleman living in semi-feudal splendor among his 3,000 tenants was an anachronism to a postwar generation that had become acclimated to Jacksonian democracy. Stephen III's leniency toward his tenants had created a serious problem for his heirs. His will directed them to collect and apply the back rents (approximately $400,000) toward the payment of the patroon's debts. As soon as the rent notices went out, the farmers organized committees and held public meetings in protest. Stephen IV, who had inherited the "West Manor" (Albany County), refused to meet with a committee of anti-renters and turned down their written request for a reduction of rents. His brusque refusal infuriated the farmers. On July 4, 1839, a mass meeting at Berne called for a declaration of independence from landlord rule but raised the amount the tenants were willing to pay.[36]

The answer to this proposal was soon forthcoming. The executors of the estate secured writs of ejectment in suits against tenants in arrears. Crowds of angry tenants manhandled Sheriff Michael Archer and his assistants and turned back a posse of 500 men. Sheriff Archer called upon Governor William H. Seward for military assistance. Seward's proclamation calling on the people not to resist the enforcement of the law and the presence of several hundred militiamen overawed the tenants. The tenants persisted in their refusal to pay rent. Of course the sheriff could and did evict a few, but he could not dispossess an entire township.[36]

By 1844 the anti-rent movement had grown from a localized struggle against the van Rensselaer family to a full-fledged revolt against leasehold tenure throughout eastern New York, where other major manors existed. Virtual guerrilla warfare broke out. Riders disguised as Indians and wearing calico gowns ranged through the countryside, terrorizing the agents of the landlords. In late 1844, Governor William Bouck sent three companies of militia to Hudson, where anti-renters threatened to storm the jail and release their leader, Big Thunder (Dr. Smith A. Boughton, in private life). The following year Governor Silas Wright was forced to declare Delaware County in a state of insurrection after an armed rider had killed undersheriff Osman N. Steele August 7, 1845 at an eviction sale.[36]

The anti-renters organized town, county, and state committees, published their own newspapers, held conventions, and elected their own spokesmen to the legislature. The success of candidates endorsed by anti-renters in 1845 caused politicians in both parties to show a "wonderful anxiety" to "give the Anti-renters all they ask." The legislature abolished the right of the landlord to seize the goods of a defaulting tenant and taxed the income which landlords derived from their rent. Shortly thereafter, the Constitutional Convention of 1846 prohibited any future lease of agricultural land which claimed rent or service for a period longer than twelve years. Yet neither the convention nor the legislature was willing to disturb existing leases.[36]

The anti-renters played politics with remarkable success in the years between 1846 and 1851. They elected friendly sheriffs and local officials who virtually paralyzed the efforts of the landlords to collect rents. They threw their weight to the candidates of either major party who would support their cause. The bitter rivalries between and within the Whig and Democratic parties enabled the anti-renters to exert more influence than their numbers warranted. As a result, they had a small but determined bloc of anti-rent champions in the Assembly and the Senate who kept landlords uneasy by threatening to pass laws challenging land titles.[36]

The anti-rent endorsement of John Young, the Whig candidate for governor in 1846, proved decisive. Governor Young promptly pardoned several anti-rent prisoners and called for an investigation of title by the Attorney General. The courts eventually ruled the statute of limitations prevented any questioning of the original titles. Declaring that the holders of perpetual leases were in reality freeholders, the Court of Appeals outlawed the "quarter sales," i.e., the requirement in many leases that a tenant who disposed of his farm should pay one-fourth of the money to the landlord.[36]

Assailed by a concerted conspiracy not to pay rent and harassed by taxes and investigations of the Attorney General, the landed proprietors gradually sold out their interests. In August 1845, seventeen large landholders announced that they were willing to sell. Later that year, Stephen IV agreed to sell his rights in the Helderberg townships. His brother, William, who had inherited the "East Manor" in Rensselaer County, also sold out his rights in over 500 farms in 1848. Finally, in the 1850s, two speculators purchased the remaining leases from the van Rensselaers.[36]

Notes

- Sometimes misspelled as Rensselaerwyck, Renselaerwick, Renslaerwick, or a multitude of other permutations. The proper Dutch spelling is Rensselaerswijck.

- The year of death is at odds in sources. Some say 1643,[16][17][18][19] some say 1645,[20][21] while the Van Rensselaer Bowier manuscripts (pp. 32) state 1646.[22]

- Although part of Albany County, the manor had its own representative to the General Assembly until 1775 and the beginning of the Revolutionary War. The seat then became defunct and its people were represented as part of Albany County.

References

- Klepper, M; Gunther, R. "The richest Americans: Stephen Van Rensselaer". Fortune Magazine. Archived from the original on 2009-04-22. Retrieved 2009-06-28.

- "Freedoms, as Given by the Council of the Nineteen of the Chartered West India Company to All those who Want to Establish a Colony in New Netherland". World Digital Library. 1630. Retrieved 2013-07-28.

- Spooner 1907, p.17

- Sylvester 1880, pp. 27–30.

-

-

-

- Spooner 1907, p. 6.

- Van Laer 1908, p. 154.

- McEneny 2006, p. 8.

- Van Rensselaer 1888, p. 7.

- Spooner 1880, p. 8.

- Spooner 1880, p. 11.

- Spooner 1880, p. 17.

- Van Laer 1908, p. 32.

- Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Gilbert, Genealogy, UMD, archived from the original on 2009-03-31.

- "KVR", New York State Museum.

- "Renßelærswijck", New Netherland Institute, archived from the original on 2010-09-21, retrieved 2008-06-25.

- Reynolds 1906, p. 40.

- Van Rensselaer 1888, p. 2.

- Van Laer 1908, p. 32.

- Reynolds 1906, p. 66.

- Bielinski, Stefan. "Jeremias Van Rensselaer". New York State Museum. Retrieved 2009-06-28.

- "The Van Rensselaer Manor House". New York State Museum. Retrieved 2009-06-28.

- Bielinski, Stefan. "Kiliaen Van Rensselaer". New York State Museum. Retrieved 2009-06-28.

- James, Edward T.; James, Janet Wilson; Boyer, Paul S.; College, Radcliffe (1971). Notable American Women, 1607-1950: A Biographical Dictionary. Harvard University Press. p. 510. ISBN 978-0-674-62734-5.

- Spooner, Walter Whipple (1900). Van Rensselaer family. p. 18.

- "Albany County". New York State Museum. Retrieved 2009-06-28.

- Bielinski, Stefan. "Rensselaerswyck". New York State Museum. Retrieved 2009-06-28.

- "The Dongan Charter". New York State Museum. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

- Bielinski, Stefan. "Hendrick Van Rensselaer". New York State Museum. Retrieved 2009-06-28.

- Bielinski, Stefan. "Stephen Van Rensselaer". New York State Museum. Retrieved 2009-06-28.

- Bielinski, Stefan. "Stephen Van Rensselaer II". New York State Museum. Retrieved 2009-06-28.

- Bielinski, Stefan. "Stephen Van Rensselaer III". New York State Museum. Retrieved 2009-06-28.

- Ellis et al. 1967, pp. 158–61.

Bibliography

- Ellis, David M; Frost, James A; Syrett, Harold C; Carman, Harry J (1967) [1957], A History of New York State, Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, ISBN 0801401186(Full text via Google Books.)

- Van Laer, AJF transl., ed. (1908), Van Rensselaer Bowier Manuscripts, Albany: University of the State of New York(Full text via Google Books.)

- McEneney, Jack J (2006). Albany: Capital City on the Hudson. Sun Valley, California: American Historical Press. ISBN 1-892724-53-7.(Full text via Google Books.)

- Van Rensselaer, Maunsell (1888), Annals of the Van Rensselaers in the United States, Albany: Charles van Benthuysen & Sons(Full text via Google Books.)

- Reynolds, Cuyler (1906), Albany Chronicles: A History of the City Arranged Chronologically, JB Lyon(Full text via Google Books.)

- Spooner, WW (January 1907), "The Van Rensselaer Family", American Historical Magazine, 2 (1): 1–23(Full text via the Internet Archive.)

- Sylvester, Nathaniel Bartlett (1880), History of Rensselaer Co., New York with Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of its Prominent Men and Pioneers, Philadelphia: Everts & Peck.

External links

- Rensselaerswijck at the Virtual Tour of New Netherland, New Netherland Project of the New Netherland Institute

- Rensselaerswyck at the Colonial Albany Social History Project of the New York State Museum