Knulp

Knulp is a 1915 novel written by Hermann Hesse. It was Hesse's most popular book in the years before he published Demian. The novel is split up into three separate tales which are centered on the life of the main character: Knulp. Knulp, who was once a gifted and promising youth, is depicted as an amiable vagabond perpetually wandering from town to town, staying with friends. He is liked by almost everyone he encounters in the novel for his manners and charming demeanour. He often receives charity from those sympathetic with him.

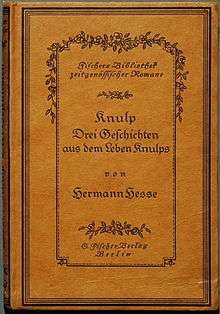

1st edition | |

| Author | Hermann Hesse |

|---|---|

| Translator | Ralph Mannheim [1] |

| Country | Germany |

| Language | German |

| Genre | Novel |

Publication date | 1915 |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover and Paperback) |

| Pages | 114 |

| Preceded by | Rosshalde |

| Followed by | Demian |

Synopsis

The first tale, titled "Early Spring", follows Knulp just after he had been discharged from a hospital due to his waning health. An old friend of his, a tanner named Emil Rothfuss, shelters him while Knulp spends his days aimlessly. During the tale he gains the affection of the tanner's wife, though he does not welcome her advances. He attempts to court a girl named Barbra Flick who had recently arrived in the town as a household servant. The chapter culminates after Knulp convinces Barbra to abandon her post in the night and dance with him. In the last words of "Early Spring", Knulp decides to leave the town despite a commitment with the tanner and his wife scheduled the following day.

The second tale, "My Recollections of Knulp", is told from the point of view of another vagrant who is not identified but is the only of the three tales written in first person giving the impression as possibly being Hermann Hesse himself. The story focuses on his interactions with Knulp as they wander through the forests and meadows of Germany. The second half of the section takes place during a day which unfolded as joy-filled and carefree. It ends, however, on the following day when Knulp has abandoned the narrator. The narrator is bewildered, wondering if possibly Knulp left him out of disgust due to his excessive drinking, the previous night.

The Third tale, "The End", follows Knulp as he is taken in for a growing illness by Dr. Machold—a childhood friend from Latin school. Dr. Machold, who once learned from Knulp, is now a grown up respectable individual. He helps Knulp to recover as they reminiscent on their brief time together, during their childhood, while, Dr. Machold prepares to send him to a hospital in the town of their youth. Upon arriving, Knulp wanders around his home town remembering what once was. He greets a stone-breaker who, after recognizing Knulp from his childhood days, questions why he never put his God given gifts and abilities to good use.

Towards the end of the novel, Knulp wanders into the forest. He begins a conversation with God, which poetically connects the three tales. In this conversation, Knulp asks God why he, Knulp, has not done anything of consequence in life. Knulp questions about the purpose of his life and why the longevity. Throughout the conversation, Knulp slowly comes to terms with himself and then accepts his life.

"See," said God, "I did not need you to be any other than you. In my name, you have wandered and have always brought the sedentary people a little homesickness for freedom. In my name you have done stupid things and made yourself a mockery; I am mocked in you and loved in you. You are my child and my brother and a piece of me, and you have tasted nothing and suffered nothing that I have not experienced with you." "Yes," Knulp said, nodding heavily. "Yes, it is so, I always knew it."[2]

References

- Hesse, Hermann (1971). Knulp: three tales from the life of Knulp. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 0374182167.

- Hermann Hesse: Knulp. Drei Geschichten aus dem Leben Knulps. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-518-38071-0, S. 123.