Richard III (1995 film)

Richard III is a 1995 British film adaptation of William Shakespeare's play of the same name, directed by Richard Loncraine. The film adapts the play's story and characters to a setting based on 1930s Britain, with Richard depicted as a fascist plotting to usurp the throne.

| Richard III | |

|---|---|

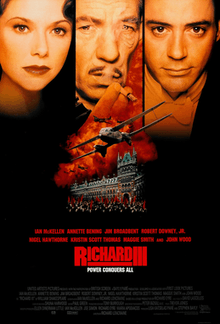

Theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | Richard Loncraine |

| Produced by |

|

| Written by | |

| Based on | Richard III by William Shakespeare |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Trevor Jones |

| Cinematography | Peter Biziou |

| Edited by | Paul Green |

Production company |

|

| Distributed by | United Artists Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 104 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | £6,000,000 |

| Box office | $2,684,904 |

Ian McKellen portrays the titular Richard, as well as co-writing the screenplay with Loncraine. The cast also includes Annette Bening as Queen Elizabeth, Jim Broadbent as the Duke of Buckingham, Robert Downey Jr. as Rivers, Kristin Scott Thomas as Anne Neville, Nigel Hawthorne as the Duke of Clarence, Maggie Smith as the Duchess of York, John Wood as King Edward IV, Tim McInnerny as Sir William Catesby, and Dominic West as the Earl of Richmond.

The film premiered in Brazil on August 20, 1995, and was released in the United States on December 29, 1995, and in the United Kingdom on April 26 of the following year. The film was critically acclaimed,[1] and won several accolades. At the 50th British Academy Film Awards, it won the awards for Best Production Design and Best Costume Design, with nominations for Best British Film, Best Adapted Screenplay, and Best Actor in a Leading Role. It also earned Oscar nominations for Best Art Direction and Best Costume Design, and McKellen was nominated for a Golden Globe Award for Best Actor – Motion Picture Drama.

Plot

In a fictitious alternate timeline of England in the late 1930s, a chaotic and bloody civil war (which occurs 450 years later than the actual historical event) ends with Lancastrian King Henry and his son Prince Edward assassinated by Field Marshal Richard Gloucester of the rival faction supported by the House of York. Richard's elder brother Edward York becomes King, while the Lancastrian heir, Henry Richmond, flees to France.

Richard is determined to take the crown, and pits King Edward against his brother, George Clarence, who is imprisoned under a sentence of death. Meanwhile, Richard deceives and marries Prince Edward's widow Lady Anne Neville.

Queen Elizabeth intercedes on Clarence's behalf and persuades Edward to spare his life. However, Richard destroys the royal pardon and commissions James Tyrrell to execute Clarence, ostensibly in compliance with Clarence's death sentence.

Richard informs Edward of Clarence's death at a meeting with Prime Minister William Hastings, and the King dies from a stroke. As Edward's sons are underage, Richard becomes Regent, taking the title of Lord Protector with the support of the ambitious and corrupt Henry Buckingham.

In order to undermine his rivals for the throne, Richard has Rivers, the Queen's brother, assassinated and uses the sordid circumstances of his death to damage the Queen's reputation and cast doubt on her sons' legitimacy. Hastings' reluctance to support Richard's claim to the crown so enrages Richard that he manufactures false charges of treason against Hastings, who is sentenced to death by hanging. Having made an example of his only vocal opponent, Richard persuades the Lord Mayor of London and members of the House of Lords to acknowledge his claim to the throne and crown him King.

Following his coronation Richard, now King Richard III, seeks to make his throne secure. He employs Tyrrell to murder the princes after failing to convince Buckingham to do so. Aware that Richmond intends to marry Elizabeth, he instructs Sir William Catesby to spread rumours that Lady Anne is ill and likely to die, intending to marry Elizabeth himself. Lady Anne is found dead sometime later from an apparent drug overdose.

Impatient for the promised reward for his loyalty, Buckingham demands the Earldom of Hereford. Richard dismisses this in a high-handed manner, with the line "I am not in the giving vein". Buckingham, also disturbed by the murders of the princes and Hastings, flees to meet Richmond, but is later captured and killed by Tyrrell under Richard's orders.

Meanwhile, Richmond gathers supporters, among them the Archbishop of Canterbury and Richard's mother, the Duchess of York. They are joined by Air marshal Thomas Stanley. Richmond marries Elizabeth and unites both Houses and political factions against Richard.

With the army's loyalty slipping and the legitimacy of his claims to the crown weakened, Richard prepares for the final battle against the Lancastrians, who plan a seaborne invasion and an advance on London. Richard's remaining loyal troops, assembling in a marshalling yard, are attacked from the air, revealing Stanley's defection to the Lancastrian cause.[2]

The two armies meet soon after at a ruined military base. Richard and Richmond seek each other out, but when his vehicle stalls Richard flees into the structure. Pursued by Richmond, Richard is forced to exit onto exposed metal beams high above the burning battlefield. Cornered by Richmond and refusing to surrender, Richard falls into the inferno with a maniacal grin.

Cast

- Ian McKellen as Richard, Duke of Gloucester, later King Richard III

- Annette Bening as Queen Elizabeth

- Jim Broadbent as the Duke of Buckingham

- Robert Downey Jr. as Rivers

- Kristin Scott Thomas as Lady Anne Neville

- Maggie Smith as the Duchess of York

- John Wood as King Edward IV

- Nigel Hawthorne as George, Duke of Clarence

- Adrian Dunbar as Sir James Tyrrel

- Edward Hardwicke as Lord Stanley

- Tim McInnerny as Sir William Catesby

- Jim Carter as Lord Hastings

- Dominic West as Henry, Earl of Richmond (the future King Henry VII)

- Trés Hanley as Lord Rivers' mistress

- Roger Hammond as Archbishop Thomas

- Donald Sumpter as Robert Brackenbury

- Bill Paterson as Richard Ratcliffe

- Kate Steavenson-Payne as Princess Elizabeth

- Christopher Bowen as Edward of Lancaster, Prince of Wales

- Matthew Groom as Prince Richard of York

- Marco Williamson as Edward of York, Prince of Wales

- Edward Jewesbury as King Henry VI

- Stacey Kent as Singer at the celebratory ball

Michael Elphick has an uncredited cameo appearance as the second murderer of Edward's sons.

Concept

The film's concept was based on a stage production Richard Eyre directed for the Royal National Theatre, which also starred McKellen. The production was adapted for the screen by McKellen and directed by Richard Loncraine.

The film is notable for its unconventional use of famous British landmarks, often using special effects to move them to new locations. The transformed landmarks include:

- St Pancras railway station, instead of the Palace of Westminster, is King Edward's seat of government.

- Battersea Power Station, relocated to the coast of Kent and portrayed as a heavily damaged military base.

- Bankside Power Station, rather than the actual Tower of London, depicted as the prison where Clarence is imprisoned. At the time of filming, the station was partially derelict, before its current use as the Tate Modern.

- Brighton Pavilion, King Edward's country retreat on a coastal clifftop.

- Senate House of the University of London, Richard's seat of government, used for interior and exterior scenes.[3] The famous art deco facade and clock of Shell Mex House is also featured in exterior shots.

The visually rich production features various symbols, uniforms, weapons, and vehicles that draw openly from fascist aesthetics, similar to those of the Third Reich as depicted in Nazi propaganda (especially Triumph of the Will) and war films.

At the same time, obvious care is put into diluting and mixing the totalitarian references with recognizable British and American uniforms, props, and visual motifs. The resulting military uniforms, for instance, range from completely standard 1930s British Army and Air Force uniforms for good characters to heavily squadristi and SS-inspired insignia on British uniforms for Richard's entourage, with SS collar tabs replacing the gorget patches and a white boar replacing the royal crown on Richard's uniform.

For road transport, great care was taken to ensure that all cars in filming were of pre-war vintage.

For air transport, pre-war types were used again to ensure authenticity. As Lord Rivers arrives, he does so in a Pan-Am DC-3 airliner. As the Duchess of York (Maggie Smith) departs for France, she does so in a DeHavilland Dragon Rapide biplane airliner. For the climactic final battle, the then-restored Bristol Blenheim is used to represent Lord Stanley's air-attack, which is also period-correct for RAF deployment immediately before and during the start of the Second World War, for the period at which the film ends.

Another example of this balanced approach to production design is the choice of tanks for battle scenes between Richmond's and Richard's armies: both use Soviet tanks (T-55s and T-34s respectively), mixed with German, American, and British World War II-era vehicles. To convey the out-of-place nature of the common-born Queen Elizabeth, she is reconfigured as an American socialite similar to Wallis Simpson, and members of the court treat her and her brother with marked disapproval.

One of the play's most famous lines—"A horse! A horse! My kingdom for a horse!"—is re-contextualized by the 20th-century setting; during the climactic battle, Richard's jeep becomes stuck in a pile of debris, and his lament is a plea for a mode of transport with legs rather than wheels.

The film enlarges the role of the Duchess of York considerably by combining her character with that of Queen Margaret, as compared with Laurence Olivier's 1955 film version of the play, in which the Duchess hardly appeared at all and Queen Margaret was completely eliminated. The roles of Rivers, Grey, Vaughan, and Dorset are combined into Rivers. The death scenes are shown rather than implied as in the play, and changed to suit the time (Hastings is hanged rather than beheaded) and historical accuracy (Clarence dies by having his throat cut in a bathtub, rather than being drowned in a wine barrel). Rivers—who usually dies offstage (or, in the case of Olivier's film, offscreen)—is impaled by a sharp spike spurting up from the bottom of his mattress while he lies in bed during sex with a woman in a hotel room. Each character's pre-death monologue is also removed, except those of Clarence and Buckingham.

McKellen wrote, "When you put this amazing old story in a believable modern setting, it will hopefully raise the hair on the back of your neck, and you won't be able to dismiss it as 'just a movie' or, indeed, as 'just old-fashioned Shakespeare'."[4]

Awards

- Academy Awards[5]

- Best Art Direction – Tony Burrough (nominated)

- Best Costume Design – Shuna Harwood (nominated)

- BAFTA Film Awards

- Best British Film (nominated)

- Best Actor – Ian McKellen (nominated)

- Best Adapted Screenplay – Ian McKellen and Richard Loncraine (nominated)

- Best Costume Design – Shuna Harwood (won)

- Best Production Design – Tony Burrough (won)

- Berlin Film Festival

- Silver Bear for Best Director – Richard Loncraine (won)[6]

- Golden Bear (nominated)

- Golden Globe Awards

- Best Actor – Motion Picture Drama – Ian McKellen (nominated)

Reception

Richard III received universal acclaim from critics. The review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes gave the film a 94% "Certified Fresh" rating based on 50 reviews, with an average score of 8.2/10.[1] Empire magazine gave the film 4/5 stars, calling it "fascinating" and "cerebral".[7] Jeffrey Lyons said the film was "mesmerizing",[8] while Richard Corliss in Time called it "cinematic".[8] Mick LaSalle of the San Francisco Chronicle wrote, "the picture never stops coming at you".[8] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film four stars out of four and included it on his Great Movies list.[9]

Soundtrack

The soundtrack to Richard III was released on February 27, 1996.

| No. | Title | Artist | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "The Invasion" | Trevor Jones | 1:37 |

| 2. | "Come Live With Me" | Stacey Kent | 5:40 |

| 3. | "Now Is the Winter of Our Discontent" | Trevor Jones | 1:01 |

| 4. | "Mortuarty" | Trevor Jones | 1:26 |

| 5. | "Bid Me Farewell/I'll Have Her" | Trevor Jones | 1:21 |

| 6. | "Clarence's Dream" | Trevor Jones | 3:04 |

| 7. | "Crimson" | Trevor Jones | 3:13 |

| 8. | "Clarence's Murder" | Trevor Jones | 2:05 |

| 9. | "The Tower" | Trevor Jones | 2:06 |

| 10. | "The Blessing" | Trevor Jones | 0:27 |

| 11. | "Conspiracy" | Trevor Jones | 0:35 |

| 12. | "Toe Tappers" | Trevor Jones | 2:14 |

| 13. | "Let Sorrow Haunt Your Bed" | Trevor Jones | 1:29 |

| 14. | "The Reach of Hell/Long Live the King" | Trevor Jones | 1:15 |

| 15. | "Good Angels Guard You" | Trevor Jones | 0:28 |

| 16. | "Coronation Haze" | Trevor Jones | 1:11 |

| 17. | "Prelude from Te Deum" | Trevor Jones | 1:41 |

| 18. | "The Golden Dew of Sleep" | Trevor Jones | 0:30 |

| 19. | "My Regret" | Trevor Jones | 2:46 |

| 20. | "Pity Dwells Not This Eye" | Trevor Jones | 0:25 |

| 21. | "Westminster" | Trevor Jones | 3:14 |

| 22. | "My Most Grievous Curse" | Trevor Jones | 0:49 |

| 23. | "The Duchess Departs" | Trevor Jones | 0:52 |

| 24. | "The Devil's Temptation" | Trevor Jones | 0:54 |

| 25. | "Richmond" | Trevor Jones | 0:52 |

| 26. | "Defend Me Still" | Trevor Jones | 2:47 |

| 27. | "I Did But Dream" | Trevor Jones | 0:45 |

| 28. | "Elizabeth and Richmond" | Trevor Jones | 1:37 |

| 29. | "My Kingdom for a Horse" | Trevor Jones | 0:39 |

| 30. | "Battle" | Trevor Jones | 4:42 |

| 31. | "I'm Sitting on Top of the World" | Al Jolson | 1:49 |

| 32. | "Come Live With Me" | Stacey Kent | 5:40 |

| Total length: | 59:14[10] | ||

"Come Live With Me" is a 1930s-style swing song, performed by Stacey Kent at the ball celebrating Edward IV's triumph. It is an original composition by Trevor Jones with anachronistic lyrics adapted from Christopher Marlowe's "The Passionate Shepherd To His Love", a poem actually written a century after the events depicted in the play.[11]

Legacy

One of the T-34 tanks used in the film, originally in service with the Czech army, can still be seen in London, permanently located on a plot of land in Bermondsey on the corner of Mandela Way and Page's Walk. It is regularly repainted by graffiti artists.

References

- "Richard III". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- "Richard III". Screenplay by Ian McKellen and Richard Loncraine. mckellen.com. Retrieved 22 April 2006.

- "Richard III: Photographs". mckellen.com. 2014. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- Stern, Keith (1995). "Richard III: Notes". Mckellen.com. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- "The 68th Academy Awards (1996) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- "Berlinale: 1996 Prize Winners". berlinale.de. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- Errigo, Angie. "Empire's Richard III Movie Review". Empireonline.com. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- Stern, Keith (1995). "Richard III: Reviews". Mckellen.com. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- Ebert, Roger (7 October 2009). "Richard III Movie Review & Film Summary (1996)". rogerebert.com. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- "Richard III Soundtrack". AllMusic. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- Rothwell, Kenneth (2004). A History Of Shakespeare On Screen: A Century Of Film And Television. Cambridge University Press. p. 222. ISBN 978-0521543118.

External links

- McKellen's website about the film including an annotated copy of the screenplay.

- Richard III on IMDb

- Richard III at Box Office Mojo

- Richard III at AllMovie