Stockport

Stockport is a large town in Greater Manchester, England, 7 miles (11 km) south-east of Manchester city centre, where the River Goyt and Tame merge to create the River Mersey. It is the largest town in the metropolitan borough of the same name.

| Stockport | |

|---|---|

View from the Stockport Viaduct | |

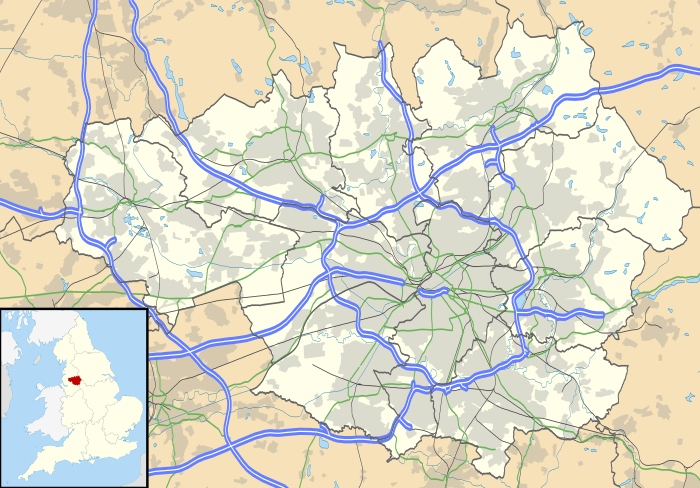

Stockport Location within Greater Manchester | |

| Population | 105,878 (2011 Census) |

| • Density | 11,937 per mi² (4,613 per km²) |

| Demonym | Stopfordian |

| OS grid reference | SJ895900 |

| • London | 157 mi (253 km) SE |

| Metropolitan borough | |

| Metropolitan county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | STOCKPORT |

| Postcode district | SK1-SK5 |

| Dialling code | 0161 |

| Police | Greater Manchester |

| Fire | Greater Manchester |

| Ambulance | North West |

| UK Parliament | |

Historically, most of the town was in Cheshire, but the area to the north of the Mersey was in Lancashire. Stockport in the 16th century was a small town entirely on the south bank of the Mersey, known for the cultivation of hemp and manufacture of rope. In the 18th century, the town had one of the first mechanised silk factories in the British Isles. However, Stockport's predominant industries of the 19th century were the cotton and allied industries. Stockport was also at the centre of the country's hatting industry, which by 1884 was exporting more than six million hats a year; the last hat works in Stockport closed in 1997.

Dominating the western approaches to the town is the Stockport Viaduct. Built in 1840, the viaduct's 27 brick arches carry the mainline railways from Manchester to Birmingham and London over the River Mersey. This structure featured as the background in many paintings by L. S. Lowry.

History

Toponymy

Stockport was recorded as "Stokeport" in 1170.[1][2] The currently accepted etymology is Old English port, a market place, with stoc, a hamlet (but more accurately a minor settlement within an estate); hence, a market place at a hamlet.[1][2] Older derivations include stock, a stockaded place or castle, with port, a wood, hence a castle in a wood.[3] The castle probably refers to Stockport Castle, a 12th-century motte-and-bailey first mentioned in 1173.[4]

Other derivations are based on early variants such as Stopford and Stockford. There is evidence that a ford across the Mersey existed at the foot of Bridge Street Brow. Stopford retains a use in the adjectival form, Stopfordian, for Stockport-related items, and pupils of Stockport Grammar School style themselves Stopfordians.[5] By contrast, former pupils of Stockport School are known as Old Stoconians. Stopfordian is used as the general term, or demonym used for people from Stockport, much as someone from London would be a Londoner.[6][7]

Stockport has never been a sea or river port as the Mersey is not navigable here; in the centre of Stockport the river has been culverted and the main shopping street, Merseyway, built above it.

Early history

The earliest evidence of human occupation in the wider area are microliths from the hunter-gatherers of the Mesolithic period (the Middle Stone Age, about 8000–3500 BC) and weapons and stone tools from the Neolithic period (the New Stone Age, 3500–2000 BC). Early Bronze Age (2000–1200 BC) remains include stone hammers, flint knives, palstaves (bronze axe heads), and funerary urns; all finds were chance discoveries, not the results of systematic searches of a known site. There is a gap in the age of finds between about 1200 BC and the start of the Roman period in about 70 AD, which may indicate depopulation, possibly due to a poorer climate.[8]

Despite a strong local tradition, there is little evidence of a Roman military station at Stockport.[9][10] It is assumed that roads from Cheadle to Ardotalia (Melandra) and Manchester to Buxton crossed close to the town centre. The preferred site is at a ford over the Mersey, known to be paved in the 18th century, but it has never been proved that this or any roads in the area are Roman. Hegginbotham reported (in 1892) the discovery of Roman mosaics at Castle Hill (around Stockport market) in the late 18th century, during the construction of a mill, but noted it was "founded on tradition only"; substantial stonework has never been dated by modern methods. However, Roman coins and pottery were probably found there during the 18th century. A cache of coins dating from 375–378 AD may have come from the banks of the Mersey at Daw Bank; these were possibly buried for safekeeping at the side of a road.[9]

Six coins from the reigns of the Anglo-Saxon English Kings Edmund (reigned 939–946) and Eadred (reigned 946–955) were found during ploughing at Reddish Green in 1789.[1][11] There are contrasting views about the significance of this; Arrowsmith takes this as evidence for the existence of a settlement at that time, but Morris states the find could be "an isolated incident". The small cache is the only Anglo-Saxon find in the area.[1] However, the etymology Stoc-port suggests inhabitation during this period.[12]

Medieval and early modern period

No part of Stockport appears in the Domesday Book of 1086. The area north of the Mersey was part of the hundred of Salford, which was poorly surveyed. The area south of the Mersey was part of the Hamestan hundred. Cheadle, Bramhall, Bredbury, and Romiley are mentioned, but these all lay just outside the town limits. The survey includes valuations of the Salford hundred as a whole and Cheadle for the times of Edward the Confessor, just before the Norman invasion of 1066, and the time of the survey. The reduction in value is taken as evidence of destruction by William the Conqueror's men in the campaigns generally known as the Harrying of the North. The omission of Stockport was once taken as evidence that destruction was so complete that a survey was not needed.[13]

Arrowsmith argues from the etymology that Stockport may have still been a market place associated with a larger estate, and so would not be surveyed separately. The Anglo-Saxon landholders in the area were dispossessed and the land divided amongst the new Norman rulers. The first borough charter was granted in about 1220 and was the only basis for local government for six hundred years.

A castle held by Geoffrey de Costentin is recorded as a rebel stronghold against Henry II in 1173–1174 when his sons revolted. There is an incorrect local tradition that Geoffrey was the king's son, Geoffrey II, Duke of Brittany, who was one of the rebels.[14] Dent gives the size of the castle as about 31 by 60 m (102 by 197 ft), and suggests it was similar in pattern to those at Pontefract and Launceston. The castle was probably ruinous by the middle of the 16th century, and in 1642 it was agreed to demolish it. Castle Hill, possibly the motte, was levelled in 1775 to make space for Warren's mill, see below.[15][16] Nearby walls, once thought to be either part of the castle or of the town walls, are now thought to be revetments to protect the cliff face from erosion.[17]

The regicide John Bradshaw (1602–1659) was born at Wibersley, in the parish of Stockport, baptised in the parish church and attended Stockport Free School. A lawyer, he was appointed lord president of the high court of justice for the trial of King Charles I in 1649. Although he was dead by the time of the Restoration in 1660, his body was brought up from Westminster Abbey and hanged in its coffin at Tyburn.[18]

Stockport bridge has been documented as existing since at least 1282. During the English Civil War the town was supportive of Parliament and was garrisoned by local militias of around 3000 men commanded by Majors Mainwaring and Duckenfield. Prince Rupert advanced on the town on 25 May 1644, with 8-10,000 men and 50 guns, with a brief skirmish at the site of the bridge, in which Colonel Washington's Dragoons led the Royalist attack. Rupert continued his march via Manchester and Bolton to meet defeat at Marston Moor near York.[19][20] Stockport bridge was pulled down in 1745 and trenches were additionally dug in the fords to try to stop the Jacobite army of Charles Edward Stuart as they marched through the town on the way to Derby. The vanguard was shot at by the town guard and a horse was killed.[19][21] The army also passed through Stockport on their retreat back from Derby to Scotland.[22][23]

One of the legends of the town is that of Cheshire farmer, Jonathan Thatcher, who, in a 1784 demonstration against taxation, avoided Pitt the Younger's saddle tax on horses by riding to market at Stockport on an ox.[24] The incident is also celebrated in 'The Glass Umbrella' in St Petersgate Gardens, one of the works on Stockport's Arts Trail.[25]

Industrialisation

Anon, 1769.[26]

Hatmaking was established in north Cheshire and south-east Lancashire by the 16th century. From the 17th century Stockport became a centre for the hatting industry and later the silk industry. Stockport expanded rapidly during the Industrial Revolution, helped particularly by the growth of the cotton manufacturing industries. However, economic growth took its toll, and 19th century philosopher Friedrich Engels wrote in 1844 that Stockport was "renowned as one of the duskiest, smokiest holes" in the whole of the industrial area.[27]

Stockport was one of the prototype textile towns.[28] In the early 18th century, England was not capable of producing silk of sufficient quality to be used as the warp in woven fabrics. Suitable thread had to be imported from Italy, where it was spun on water-powered machinery. In about 1717 John Lombe travelled to Italy and copied the design of the machinery. On his return he obtained a patent on the design, and went into production in Derby. When Lombe tried to renew his patent in 1732, silk spinners from towns including Manchester, Macclesfield, Leek, and Stockport successfully petitioned parliament to not renew the patent. Lombe was paid off, and in 1732 Stockport's first silk mill (the first water-powered textile mill in the north-west of England) was opened on a bend in the Mersey. Further mills were opened on local brooks.

Silk weaving expanded until in 1769 two thousand people were employed in the industry. By 1772 the boom had turned to bust, possibly due to cheaper foreign imports; by the late 1770s trade had recovered.[26] The cycle of boom and bust would continue throughout the textile era.

The combination of a good water power site (described by Rodgers as "by far the finest of any site within the lowland" [of the Manchester region][28]) and a workforce used to textile factory work meant Stockport was well placed to take advantage of the phenomenal expansion in cotton processing in the late 18th century. Warren's mill in the market place was the first. Power came from an undershot water wheel in a deep pit, fed by a tunnel from the River Goyt. The positioning on high ground, unusual for a water powered mill, contributed to an early demise, but the concept of moving water around in tunnels proved successful, and several tunnels were driven under the town from the Goyt to power mills.[29] In 1796, James Harrisson drove a wide cut from the Tame which fed several mills in the Park, Portwood.[30] Other water-powered mills were built on the Mersey.

The town was connected to the national canal network by the 5 miles (8.0 km) of the Stockport branch of the Ashton Canal opened in 1797 which continued in use until the 1930s. Much of it is now filled in, but there is an active campaign to re-open it for leisure uses.

In the early 19th century, the number of hatters in the area began to increase, and a reputation for quality work was created. The London firm of Miller Christy bought out a local firm in 1826, a move described by Arrowsmith as a "watershed". By the latter part of the century hatting had changed from a manual to a mechanised process, and was one of Stockport's primary employers; the area, with nearby Denton, was the leading national centre. Support industries, such as blockmaking, trimmings, and leatherware, became established. Stockport Armoury was completed in 1862.[31]

The First World War cut off overseas markets, which established local industries and eroded Stockport's eminence. Even so, in 1932 more than 3000 people worked in the hatting industry, making it the third biggest employer after textiles and engineering. The depression of the 1930s and changes in fashion greatly reduced the demand for hats, and the demand that existed was met by cheaper wool products made elsewhere, for example the Luton area.

In 1966, the largest of the region's remaining felt hat manufacturers, Battersby & Co, T & W Lees, J. Moores & Sons, and Joseph Wilson & Sons, merged with Christy & Co to form Associated British Hat Manufacturers, leaving Christy's and Wilson's (at Denton) as the last two factories in production. The Wilson's factory closed in 1980, followed by the Christy's factory in 1997, bringing to an end over 400 years of hatting in the area.[32][33][34] The industry is commemorated by the UK's only dedicated hatting museum, Hat Works.[35][36]

Recent history

Since the start of the 20th century Stockport has moved away from being a town dependent on cotton and its allied industries to one with a varied base. It makes the most of its varied heritage attractions, including a national museum of hatting, a unique system of Second World War air raid tunnel shelters in the town centre, and a late medieval merchants' house on the 700-year-old Market Place. In 1967, the Stockport air disaster occurred, when a British Midland Airways C-4 Argonaut aeroplane crashed in the Hopes Carr area of the town, resulting in 72 deaths among the passengers and crew.

On 23 November 1981, an F1/T2 tornado formed over Cheadle Hulme and subsequently passed over Stockport town centre, causing some damage to the town centre and surrounding areas.[37]

Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council has embarked on an ambitious regeneration scheme, known as Future Stockport. The plan is to bring more than 3000 residents into the centre of the town, and revitalise its residential property and retail markets in a similar fashion to the nearby city of Manchester. Many ex-industrial areas around the town's core will be brought back into productive use as mixed-use residential and commercial developments. Property development company FreshStart Living has been involved in redeveloping a former mill building in the town centre, St Thomas Place. The company plan to transform the mill into 51 residential apartments as part of the regeneration of Stockport.[38]

Governance

Civic history

Stockport was a township mostly within the Macclesfield Hundred within the historic county of Cheshire with a small part on the north side of the Mersey in Lancashire.[39] The Municipal Corporations Act 1835 made Stockport a municipal borough divided into six wards with a council consisting of 14 aldermen and 42 councillors. Under the terms of the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834, Stockport Poor Law Union was established on 3 February 1837 and was responsible for an area covering 16 parishes with a total population of 68,906. Stockport Union built a workhouse at Shaw Heath in 1841.[40] In 1888, its status was raised to County Borough, becoming the County Borough of Stockport. In 1974, under the Local Government Act 1972, Stockport amalgamated with neighbouring districts to form the Metropolitan Borough of Stockport in the metropolitan county of Greater Manchester.

In 1986, Greater Manchester County Council was abolished and Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council assumed many of its functions, effectively becoming a unitary authority.

In 2011, Stockport bid for city status as part of the 2012 Queen's Diamond Jubilee celebrations[41] but was unsuccessful.

Parliamentary representation

There are four parliamentary constituencies in the Stockport Metropolitan Borough: Stockport, Cheadle, Hazel Grove, and Denton and Reddish. Stockport has been represented by the Labour MP Nav Mishra since 2019. Mary Robinson has been the Conservative MP for Cheadle since 2015;[42] and William Wragg has been the Conservative MP for Hazel Grove since 2015.[43] The constituency of Denton and Reddish bridges Stockport and Tameside; the current member is Andrew Gwynne for the Labour Party.[44]

Council

There are 21 electoral wards in Stockport, each with three councillors, giving a total of 63 councillors with one-third elected three years out of four.

| Party | Seats | Current Council (March 2018)[45] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014[46] | 2015[47] | 2016[48] | As of March 2018[45] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Labour | 22 | 21 | 23 | 23 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Liberal Democrats | 28 | 26 | 23 | 21 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Conservative | 10 | 13 | 14 | 14 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heald Green Ratepayers | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Independent | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Geography

| Stockport | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

At 53°24′30″N 2°8′58″W (53.408°, −2.149°) Stockport is on elevated ground, 6.1 miles (9.8 km) south-east of Manchester city centre, at the confluence of the rivers Goyt and Tame, creating the River Mersey. It shares a common boundary with the City of Manchester.

Stockport stands on Permian sandstones and red Triassic sandstones and mudstones, mantled by thick deposits of till and pockets of sand and gravel deposited by glaciers at the end of the last glacial period, some 15,000 years ago.[49] To the extreme east is the Red Rock fault, and the older rocks from the Upper Carboniferous period surface. An outcrop of Coal Measures extends southwards through Tameside and into Hazel Grove.[49] To the east, the sandstones and shales of Millstone Grit are present as outcrops on the upland moors of Dark Peak and South Pennines, and, to the south, are the limestones of the White Peak.

Divisions and suburbs

Demography

| Stockport Compared | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 UK census | Stockport[50] | Stockport MB[51] | England |

| Total population | 136,082 | 284,528 | 49,138,831 |

| White | 95.5% | 95.7% | 91% |

| Asian | 2.0% | 2.1% | 4.6% |

| Black | 0.5% | 0.4% | 2.3% |

| Christian | 74.9% | 75.4% | 72% |

| Muslim | 1.8% | 1.8% | 3.1% |

| No religion | 15.3% | 14.2% | 15% |

At the 2001 UK census, Stockport had a population of 136,082. The 2001 population density was 11,937 per mi² (4,613 per km2), with a 100 to 94.0 female-to-male ratio.[52] Of those over 16 years old, 32% were single (never married) and 50.2% married.[53] Stockport's 58,687 households included 33.1% one-person, 33.7% married couples living together, 9.7% were co-habiting couples, and 10.4% single parents with their children, these figures were similar to those of Stockport Metropolitan Borough and England.[54] Of those aged 16–74, 29.2% had no academic qualifications, significantly higher than that of 25.7% in all of Stockport Metropolitan Borough but similar to the whole of England average at 28.9%.[51][55]

Although suburbs such as Woodford, Bramhall and Hazel Grove rank amongst the wealthiest areas of the United Kingdom and 45% of the borough is green space, districts such as Edgeley, Adswood, Shaw Heath and Brinnington suffer from widespread poverty and post-industrial decay. In the north-west of the borough are the prosperous areas of Heaton Moor and Heaton Mersey, which together with Heaton Chapel and Heaton Norris comprise the so-called Four Heatons.

Population change

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: County Borough 1901–1971;[56] Urban Subdivision 1981–2001[57][58][59][60] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Economy

Stockport's principal commercial district is the town centre, with branches of most high-street stores to be found in the Merseyway Shopping Centre or The Peel Centre. Redrock Stockport has a ten-screen cinema, bars and several restaurants. Stockport is six miles (9.7 km) from Manchester, making it convenient for commuters and shoppers. In 2008, the council's £500 million plans to redevelop the town centre were cancelled after construction company Lend Lease Corporation pulled out of the project, blaming the credit crunch. More recently work has begun with talks of a metrolink to Manchester, redevelopment of the old bus station amongst many old buildings becoming luxury apartments. Also many roadworks to deal with the intended growth from the development.

Landmarks

Stockport Town Hall, designed by Sir Alfred Brumwell Thomas, has a ballroom described by John Betjeman as "magnificent" which contains the largest Wurlitzer theatre organ in Britain. The war memorial and art gallery are on Greek Street, opposite the town hall. Underbank Hall is a Grade II* listed late 16th-century timber framed building which was the townhouse of the Arderne family from Bredbury who occupied it until 1823.[61] Since 1824, it has been used as a bank and its main banking hall lies behind the 16th-century structure and dates from 1915.[17]

Stockport Viaduct is 111 feet (34 m) high, and carries four railway tracks over the River Mersey on the line to Manchester Piccadilly. The viaduct built of 11,000,000 bricks, a major feat of Victorian engineering, was completed in 21 months at a cost of £70,000.[62] The structure is Grade II* listed.[63]

Beside the M60 motorway is the Stockport Pyramid, a distinctive structure designed by Christopher Denny from Michael Hyde and Associates. It has a steel frame covered with mostly blue glass and clear glass paneling at the apex and was intended to be the signature building for a much larger development planned in 1987. Construction began in the early 1990s and it was completed in 1992 but an economic downturn caused the project to be abandoned as the developers went into administration. The building lay empty until 1995 when The Co-operative Bank repossessed it and opened it as a call centre.

Vernon Park, to the east towards Bredbury, was opened on 20 September 1858 on the anniversary of the Battle of Alma in the Crimean War. It was named after Lord Vernon who presented the land to the town.

St Elisabeth's Church, Reddish and the model village are parts a mill community designed in the main by Alfred Waterhouse for workers of Houldsworth Mill, which was once the largest cotton mill in the world.

Transport

Road

The Manchester orbital M60 motorway and the A6, which connects Carlisle with Luton, cross at Stockport.

Railway

Stockport railway station is a principal station on the Manchester spur of the West Coast Main Line. It is served by Avanti West Coast, CrossCountry, East Midlands Railway, Northern Trains, TransPennine Express and Transport for Wales services.

Stockport Tiviot Dale station also served the town centre between 1865 and 1967, lying on routes from Manchester Central to Liverpool, Derby and Sheffield. Most of the station site now lies under the M60 motorway.[64]

Air

Manchester Airport, the busiest in the UK outside London,[65] is five miles (8.0 km) south-west of the town, which lies under the airport's flightpath. Historically known as Ringway airport, the area formed part of the Stockport Metropolitan Borough until it transferred to Manchester.

Bus

Stockport bus station, which serves as a terminus for many services across the borough, is one of the largest and busiest bus stations in Greater Manchester. Frequent services to Manchester city centre are provided by Stagecoach Manchester's high frequency 192 service, which also connects the town centre with Stepping Hill Hospital and Hazel Grove. Other services to Manchester include routes 42, 197 and 203.

Education

Stockport College is based in the town centre. Also Stockport is home to Stockport Grammar School, established in 1487, one of the oldest in the north-west of England.

Religion

St Mary's Church, the town's oldest place of worship, was the centre of a large ecclesiastical parish covering Bramhall, Bredbury, Brinnington, Disley, Dukinfield, Hyde, Marple, Norbury, Offerton, Romiley, Stockport Etchells, Torkington and Werneth.[39] Chapels and churches were built in those townships and the parish today covers a much smaller area. Parts of the church, situated by the market place, date to the early 14th century and it houses the Stockport Heritage centre, run by volunteers on market days. The church is Grade I listed.[66] In the town are the Grade II listed Roman Catholic St Joseph's Church and Our Lady and the Apostles Church.[67][68]

Culture

Stockport's museums include the Hat Works in Wellington Mill, a former hat factory,[69] and Stockport Air Raid Shelters in the tunnels dug in the Second World War to protect inhabitants in air raids.[70] Staircase House, a Grade II* listed medieval townhouse,[71][17] houses the Stockport Story Museum.[72]

The Plaza is a Grade II* listed Super Cinema and Variety Theatre built in 1932.[73] It is the last venue of its kind operating in its original format, making it of international significance.[74]

In 2018, a new leisure complex opened called Redrock Stockport providing facilities including a cinema, restaurants, bars and a gym.[75] In the same year, it was named by Building Design magazine as the "worst new building" in its annual Carbuncle Cup competition.[76]

Strawberry Studios at No. 3 Waterloo Road was a recording studio from 1968 to 1993, partly owned and used extensively by 10cc, as well as many other major artists including Joy Division, Neil Sedaka, Barclay James Harvest, The Smiths, The Stone Roses, Paul McCartney and St Winifred's School Choir.

Local writer Simon Stephens' play Port is set in and around Stockport. The play has been performed at the National Theatre, London.

The painter Alan Lowndes featured Stockport scenes in his work.

The indie pop band Blossoms are from Stockport.[77]

The indie rock band Derailer are also from Stockport[78]

Paul Eastham, the front man of folk rock band COAST, was born in Stockport in July 1981 at Stepping Hill Hospital.[79]

Claire Foy, an actress who is best known for her main role in The Crown as Queen Elizabeth II, was born in Stockport in April 1984 at Stepping Hill Hospital

The BBC Radio comedy programme "Stockport, so good they named it once" was set in the town. Two series were recorded.[80]

The singer Barb Jungr released an album entitled "Stockport to Memphis" in 2012 inspired by her memories of 1960s Stockport.[81]

The 18th century composer and organist of the Manchester Collegiate Church (later Manchester Cathedral), John Wainwright, composed the hymn tune, "Yorkshire (Stockport)", to the Christmas hymn, "Christians Awake, Salute the Happy Morn", by John Byrom.

Sport

Athletics

Stockport has three athletics clubs: Manchester Harriers & AC, Stockport Harriers & AC and DASH Athletics Club. Manchester Harriers train at William Scholes' Playing Fields in Gatley and they organise highly regarded schools cross country races throughout the winter. Stockport Harriers are based at Woodbank Park in Offerton; they have several international middle-distance and endurance athletes including Andy Nixon. DASH Athletics Club are the newest club in Stockport based at both Hazel Grove Recreation Centre and the Manchester Regional Arena at Sportcity in Manchester. In 2006, DASH AC Coach Geoff Barratt was UK Athletics' Development Coach of the Year and, in 2007, the club won England Athletics North West Junior Club and North West Overall Club of the Year accolades.

Football

Stockport County F.C. play in the National League (division). The club was formed in 1883 as Heaton Norris Rovers, changing its name to Stockport County in 1890 to reflect the town's status as a county borough. It joined the Football League in 1900. Its most successful season was the 1996–97 season, when it reached the Football League Cup semi-finals and won promotion to Division One.

Stockport's second team, Stockport Town F.C., play in the NWCFL Division One and are based in Woodley.[82]

Stockport Sports F.C. (formerly Woodley Sports) was another non-League football club that played in the town. In their final season, the club competed in the NWCFL Premier Division before dissolving in 2015, due to a breach of numerous league rules.[83][84]

Lacrosse

Stockport Lacrosse Club which plays at Stockport Cricket Club, Cale Green, was founded in 1876 and its first match was played as Shaw Heath Villa. It is reputed to be the oldest club in the world and has men's, ladies' and junior teams. There are lacrosse clubs at Norbury (Hazel Grove) Cheadle, Cheadle Hulme, Heaton Mersey, Heaton Mersey Guild (now merged with Manchester Waconians) [85] and Mellor. Stockport Grammar School Old Boys (Old Stopfordians) merged with Norbury in 2013. Edgeley Park hosted the 1978 Lacrosse World Cup.

Rugby league

When the rugby football schism occurred in 1895, Stockport RFC, founded in 1895, became a founder member of the Northern Rugby Football Union (now Rugby Football League). Stockport played for eight seasons from the 1895–96 season to the end of 1902–1903 season, the latter two seasons played at Edgeley Park, the club finished 17th of 22 in the initial combined league, then 5th, 11th, 11th, 9th, 12th, 6th, in the 14-club Lancashire Senior Competition, and then 18th of 18 in Division 2 of the recombined league, after which it withdrew from the Northern Rugby Football Union.

Rugby union

Sale Sharks Rugby Union Club played at Edgeley Park from 2002 to 2012, when they moved to the AJ Bell Stadium in Barton-upon-Irwell.

Swimming

Stockport Metro Swimming Club, based at Grand Central Pools, is the most successful British swimming club over the last three Olympic Games. Stockport Metro swimmers have claimed 50% of British swimming's medal haul. At the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta, Graeme Smith won bronze in the 1500m freestyle,[86] and, at the 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens, Steve Parry won bronze in the 200m butterfly.[87] Most recently, at the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, Keri-Anne Payne and Cassie Patten won silver and bronze, respectively, in the 10 km open water swim.[88]

Tennis

Stockport is the birthplace of former World No.1 tennis player Fred Perry; winner of 8 Grand Slam singles titles, 2 Pro Slams singles titles, 2 doubles titles and 4 mixed-double titles. He was the first person to complete a Career Grand Slam and also won the Davis Cup on four consecutive occasions (1933-1936). Liam Broady and his sister Naomi Broady, the tennis professionals, were born in Stockport, attending Tithe Barn and then Priestnall School.

Youth organisations

The Stockport area is covered by several different cadet units. A unit of Sea Cadet Corps based near the Pear Mill Industrial Estate and several squadrons of the Air Training Corps, based on the A6 opposite St George's Church and others on Reddish Road in South Reddish. Stockport also has a youth council, Stockport Youth Partnership, which is based in Grand Central.

Twin towns

Stockport is twinned with:[89]

Freedom of the Borough

The following people and military units have received the Freedom of the Borough of Stockport.

Individuals

- Fred Perry: 1934.

- Christopher Finney GC: 5 September 2007.

Military units

- The Cheshire Regiment: 1969.[90]

- 1st Battalion The Mercian Regiment: 11 November 2010.[91]

See also

References

- Arrowsmith (1997), p. 23

- Mills (1997)

- "Local History", Stockport MBC web pages, archived from the original on 18 June 2006, retrieved 2 April 2007

- Historic England, "Stockport Castle (1085399)", PastScape, retrieved 5 January 2008

- "Stockport Grammar School:Old Stopfordians' Association". Stockport Grammar School. Archived from the original on 4 April 2008. Retrieved 3 April 2007.

- Davis, Matthew (27 October 2014). "Stockport playwright's latest production coming to Manchester". Manchester Evening News. Archived from the original on 8 April 2016. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- Lucas, Dan; Pickup, Oliver (26 January 2015). "Transfer news and rumours: January 26 live". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- Arrowsmith (1997), pp. 9–14

- Arrowsmith (1997), pp. 18–19

- Dent (1977), p. 1

- Morris (1983), pp. 13–15:"... foolhardy to attempt any historical interpretation of the pre-10th century evidence. (it) could represent an isolated incident."

- Dent (1977), pp. 1–2

- Husain (1973), p. 12

- See Dent 1977 for the traditional view; and Arrowsmith 1997, p. 31 for the refutation.

- Dent (1977), p. 2

- Pevsner & Hubbard (1971), p. 338

- Arrowsmith 1996, p. ?

- ODNB entry: Retrieved 30 January 2012. Subscription required

- Stockport Through Time, Coral Dranfield, Amberley Publishing Limited, 10 September 2013

- The Great Civil War in Lancashire, 1642-1651, Ernest Broxap, Manchester University Press, 1973, Great Britain, p117

- "The Scottish Historical Review, VOL. VI., No. 23 APRIL 1909, 'The Highlanders at Macclesfield in 1745'" (PDF). yourphotocard.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- "The Battle Of Clifton Moor 1745". http://www.thesonsofscotland.co.uk. Archived from the original on 27 October 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2018. External link in

|website=(help) - Elliot-Wright, Phillip JC. "Prince Maurice's Dragoones - Prince Maurice's Dragoones - A Short History". http://www.princemauricesregiment.org.uk. Archived from the original on 31 October 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2018. External link in

|website=(help) - Gentleman's Magazine and Historical Review, Volume 59, Part 2, p1210, 1789

- "Town Centre Artworks - Stockport Youth Offending Service". archive.org. 14 September 2014. Archived from the original on 14 September 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2018.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Arrowsmith (1997), pp. 97–101

- Engels, Frederick (1969) [1845], The Condition of the Working Class in England, Panther, ISBN 0-89733-137-0, archived from the original on 21 April 2006,

Stockport is renowned throughout the entire district as one of the duskiest, smokiest holes, and looks, indeed, especially when viewed from the viaduct, excessively repellent.

- Rodgers 1962, p. 13

- Dranfield (2006)

- Arrowsmith 1997, p. 130; Ashmore (1975).

- "Stockport". The Drill Halls Project. Archived from the original on 19 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- McKnight (2000), pp. 1–9

- Arrowsmith (1997), pp. 156–7

- Arrowsmith (1997), pp. 225–6

- Hat Works Museum:About us, Hat Works, archived from the original on 21 September 2008, retrieved 2 October 2008

- Williamson, Hannah (2006), "The Character of Hat Works", Manchester Region History Review, 17 (2): 111–121

- "European Severe Weather Database". www.eswd.eu.

- "FreshStart Living in £3.75m mill project", Manchester Evening News, archived from the original on 17 December 2011, retrieved 29 March 2012

- Stockport, GenUKI, archived from the original on 1 December 2011, retrieved 24 November 2011

- Stockport, workhouses.org.uk, archived from the original on 17 November 2010, retrieved 16 August 2009

- "Stockport Council - Stockport City Bid for 2012 Video". archive.org. 18 July 2012. Archived from the original on 18 July 2012. Retrieved 2 May 2018.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "Mary Robinson MP". parliament.uk. UK Parliament. Archived from the original on 19 March 2018. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- "Mr William Wragg MP". parliament.uk. UK Parliament. Archived from the original on 20 March 2018. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- "Andrew Gwynne MP". parliament.uk. UK Parliament. Archived from the original on 9 March 2018. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- "Your Councillors by Party". democracy.stockport.gov.uk. Stockport MBC. 23 March 2018. Archived from the original on 2 February 2018. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- "Local Election 2014 - Thursday, 22nd May, 2014". democracy.stockport.gov.uk. Stockport MBC. 23 May 2014. Archived from the original on 23 March 2018. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- "Local Election 2015 - Thursday, 7th May, 2015". democracy.stockport.gov.uk. Stockport MBC. 8 May 2015. Archived from the original on 23 March 2018. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- "Local Election 2016 - Thursday, 5th May, 2016". democracy.stockport.gov.uk. Stockport MBC. 6 May 2016. Archived from the original on 23 March 2018. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- Natural England. "Greater Manchester (including: Wigan, Bolton, Salford, Trafford, Bury, Rochdale, Stockport, Manchester, Tameside and Oldham)". naturalengland.org.uk. Archived from the original on 27 March 2012. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS06 Ethnic group

- Stockport Metropolitan Borough key statistics, Statistics.gov.uk, archived from the original on 25 May 2011, retrieved 1 November 2009 Retrieved on 17 August 2008.

•Stockport Metropolitan Borough ethnic group data, Statistics.gov.uk, archived from the original on 25 May 2011, retrieved 1 November 2009 Retrieved on 17 August 2008. - "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS01 Usual resident population

- "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS04 Marital status

- KS20 Household composition: Census 2001, Key Statistics for urban areas, Statistics.gov.uk, 2 February 2005, archived from the original on 29 June 2011, retrieved 5 August 2008

•Stockport Metropolitan Borough household data, Statistics.gov.uk, archived from the original on 25 May 2011, retrieved 1 November 2009 Retrieved on 17 August 2008. - "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS13 Qualifications and students

- Stockport County Borough, Vision of Britain, archived from the original on 4 June 2011 Retrieved on 24 July 2008.

- 1981 Key Statistics for Urban Areas GB Table 1, Office for National Statistics, 1981

- 1991 Key Statistics for Urban Areas, Office for National Statistics, 1991

- "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS01 Usual resident population

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 18 October 2016. Retrieved 1 September 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- 1 Great Underbank, Heritage Gateway, retrieved 31 October 2009

- Historic England, "Stockport Railway Viaduct (76880)", PastScape, retrieved 1 November 2009

- Railway Viaduct, Stockport, Heritage Gateway, retrieved 1 November 2009

- Fox 1986, pp. 76–80

- Wilson, James (26 April 2007), "A busy hub of connectivity", Financial Times – FT report – doing business in Manchester and the NorthWest

- Historic England, "Parish Church of St Mary (1309701)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 24 November 2011

- Stockport - St Joseph Archived 30 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine from English Heritage, retrieved 4 February 2016

- [http://taking-stock.org.uk/Home/Dioceses/Diocese-of-Shrewsbury/Stockport-Our-Lady-and-the-Apostles/ Stockport - Our Lady and the Apostles Archived 5 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine from English Heritage, retrieved 4 February 2016

- Visiting the Hat Works Museum, Hat works, archived from the original on 29 November 2011, retrieved 23 November 2011

- Stockport Air Raid Shelters, Stockport Air Raid Shelters, archived from the original on 6 August 2010, retrieved 23 November 2011

- Staircase Cafe, Heritage Gateway, retrieved 31 October 2009

- Stockport Story Museum, Stockport Story Museum, archived from the original on 30 June 2007, retrieved 1 November 2009

- Plaza Cinema, Heritage Gateway, retrieved 31 October 2009

- The Plaza Stockport, Stockport Plaza, archived from the original on 13 November 2011, retrieved 23 November 2011

- "What's at Redrock Stockport? The Light Cinema, PizzaExpress, Zizzis". Redrock Stockport. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- "Winner of 2018 Carbuncle Cup announced". bdonline.co.uk. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- Youngs, Ian. "BBC Sound of 2016: Blossoms". BBC News. Archived from the original on 15 January 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- "Derailer | Festival Hub | Manchester Food & Drink Festival 2018". foodanddrinkfestival.com. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- Paul Eastham Biography, archived from the original on 3 March 2017, retrieved 2 March 2017

- BBC Radio, BBC Radio, archived from the original on 13 November 2012, retrieved 16 August 2017

- "Barb Jungr - STOCKPORT TO MEMPHIS". http://www.barbjungr.co.uk. Retrieved 9 January 2019. External link in

|website=(help) - Ian Templeman. "http://www.nwcfl.com - News - Stockport Town Admitted To The NWCFL". nwcfl.com. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 15 November 2015. External link in

|title=(help) - "Stockport Sports suspended". NonLeagueReview.com. 23 January 2015. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- Templeman, Ian (2 March 2015). "Stockport Sports". nwcfl.com. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- N

- The Water Zone Profiles – Graeme Smith, archived from the original on 16 January 2007, retrieved 26 September 2008

- It's a swimming bronze for Stockport, BBC, archived from the original on 9 February 2012, retrieved 26 September 2008

- British duo take 10 km swim medals, BBC, 20 August 2008, archived from the original on 10 September 2008, retrieved 26 September 2008

- Twin Towns and Link Areas, Stockport.gov.uk, archived from the original on 18 June 2012, retrieved 1 April 2013

- http://democracy.stockport.gov.uk/mgConvert2PDF.aspx?ID=57043

- "Mercian Regiment get freedom of the borough at Stockport 'homecoming'". Stockport Express. 10 November 2010. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012.

Bibliography

- Arrowsmith, Peter (1996), Recording Stockport's Past: Recent Investigations of Historic Sites in the Borough of Stockport, Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council, ISBN 0-905164-20-2

- Arrowsmith, Peter (1997), Stockport: a History, Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council, ISBN 0-905164-99-7

- Dent, J. S. (1977), "Recent investigations on the site of Stockport Castle", Transactions of the Lancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Society, 79: 1–13

- Dranfield, Coral (2006), Rivers Under Your Feet: The Story of Stockport's Water tunnels, Kevin Dranfield, ISBN 0-9553995-0-5

- Fox, Gregory K. (1986), The Railways around Stockport, Foxline Publishing, ISBN 1-870119-00-2

- Husain, B. M. C. (1973), Cheshire under the Norman Earls, A history of Cheshire, 4, Cheshire Community Council Publications Trust

- McKnight, Penny (2000), Stockport hatting, Stockport M.B.C., Community Services Division, ISBN 0-905164-84-9

- Mills, A. D. (1997), Dictionary of English Place-Names (2nd ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-280074-4

- Morris, Mike, ed. (1983), Medieval Manchester: A Regional Study. The Archaeology of Greater Manchester volume 1, Greater Manchester Archaeological Unit, ISBN 0-946126-02-X

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Hubbard, Edward (1971), Cheshire, The buildings of England, Penguin, ISBN 0-14-071042-6

- Rodgers, H. B. (1962), "The landscapes of eastern Lancastria", in Carter, Charles (ed.), Manchester and its region: a survey prepared for the meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science held in Manchester August 29 to September 5, 1962, Manchester University Press, pp. 1–16

Further reading

- Cliffe, Steve (2005). Stockport History and Guide. Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-3525-6.

- Glen, Robert (1984). Urban workers in the early Industrial Revolution. Croom Helm. ISBN 0-7099-1103-3.

- Harris, Brian; Thacker, Alan; Lewis, C. P. (1979). A history of the county of Chester. The Victoria history of the counties of England. 2. Oxford University Press for the Institute of Historical Research. ISBN 0-19-722749-X.

- Hartwell, Clare; Hyde, Matthew; Pevsner, Nikolaus (2004). Lancashire: Manchester and the South-East. The buildings of England. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10583-5.

- Holden, Roger N. (1998). Stott & Sons: architects of the Lancashire cotton mill. Carnegie. ISBN 1-85936-047-5.

- Jenkins, Simon (1999). England's thousand best churches. Allen Lane. ISBN 0-7139-9281-6.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (1969). Lancashire. The buildings of England. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-071036-1.

- Williams, Mike; Farnie, D. A. (1992). Cotton mills in Greater Manchester. Carnegie. ISBN 0-948789-69-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stockport. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Stockport. |

- Stockport Council

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

.jpg)