Ashton-under-Lyne

Ashton-under-Lyne is a market town in Tameside, Greater Manchester, England.[1] The population was 45,198 at the 2011 census.[2] Historically in Lancashire, it is on the north bank of the River Tame, in the foothills of the Pennines, 6.2 miles (10.0 km) east of Manchester.

| Ashton-under-Lyne | |

|---|---|

Ashton-under-Lyne town centre | |

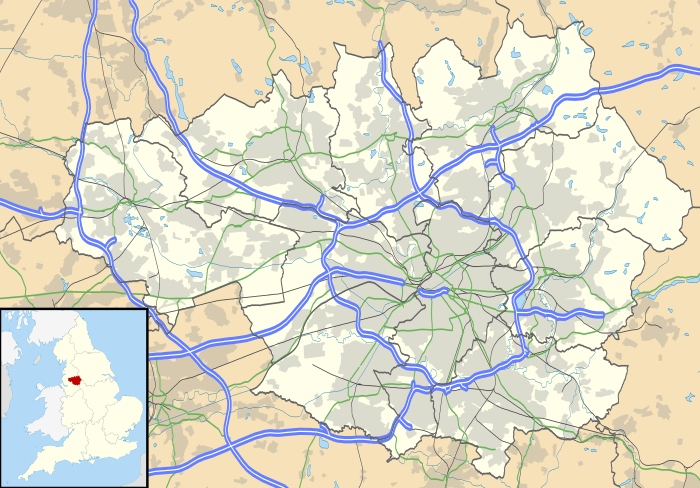

Ashton-under-Lyne Location within Greater Manchester | |

| Population | 45,198 (2011 Census) |

| • Density | 12,374 per mi² (4,777 per km²) |

| OS grid reference | SJ931997 |

| • London | 160 mi (257 km) SSE |

| Metropolitan borough | |

| Metropolitan county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | ASHTON-UNDER-LYNE |

| Postcode district | OL6, OL7 |

| Dialling code | 0161 |

| Police | Greater Manchester |

| Fire | Greater Manchester |

| Ambulance | North West |

| UK Parliament | |

Evidence of Stone Age, Bronze Age, and Viking activity has been discovered in Ashton-under-Lyne. The "Ashton" part of the town's name probably dates from the Anglo-Saxon period, and derives from Old English meaning "settlement by ash trees". The origin of the "under-Lyne" suffix is less clear;[3] it possibly derives from the British lemo meaning elm or from Ashton's proximity to the Pennines.[4] In the Middle Ages, Ashton-under-Lyne was a parish and township and Ashton Old Hall was held by the de Asshetons, lords of the manor. Granted a Royal Charter in 1414, the manor spanned a rural area consisting of marshland, moorland, and a number of villages and hamlets.

Until the introduction of the cotton trade in 1769, Ashton was considered "bare, wet, and almost worthless".[4] The factory system, and textile manufacture during the Industrial Revolution triggered a process of unplanned urbanisation in the area, and by the mid-19th century Ashton had emerged as an important mill town at a convergence of newly constructed canals and railways. Ashton-under-Lyne's transport network allowed for an economic boom in cotton spinning, weaving, and coal mining, which led to the granting of municipal borough status in 1847.

In the mid-20th century, imports of cheaper foreign goods led to the decline of Ashton's heavy industries but the town has continued to thrive as a centre of commerce[5] and Ashton Market is one of the largest outdoor markets in the United Kingdom. Ashton Town Centre is now home to the 140,000-square-foot (13,000 m2), two-floored Ashton Arcades shopping centre (opened 1995), the outdoor shopping complex Ladysmith Shopping Centre, and a large IKEA store.

In 2018, a large new development opened in Ashton town centre including a new college campus for Tameside College, new council offices and a library. Improvements were also made to the open-air market, including new kiosks and stalls. In 2019, work began on a brand-new transport interchange for the town centre to make getting into the town much easier via bus and Metrolink. This is scheduled to open in late 2020.

History

Evidence of prehistoric activity in the area comes from Ashton Moss – a 107-hectare (260-acre) peat bog – and is the only one of Tameside's 22 Mesolithic sites not located in the hilly uplands in the north east of the borough. A single Mesolithic flint tool has been discovered in the bog,[6][7] along with a collection of nine Neolithic flints.[8] There was further activity in or around the bog in the Bronze Age. In about 1911, an adult male skull was found in the moss; it was thought to belong to the Romano-British period – similar to the Lindow Man bog body – until radiocarbon dating revealed that it dated from 1,320–970 BC.[9][10]

The eastern terminus of the early medieval linear earthwork Nico Ditch is in Ashton Moss (grid reference SJ909980); it was probably used as an administrative boundary and dates from the 8th or 9th century. Legend claims it was built in a single night in 869 or 870 as a defence against Viking invaders.[11][12] Further evidence of Dark Age activity in the area comes from the town's name. The "Ashton" part probably derives from the Anglo-Saxon meaning "settlement by ash trees";[13][14] the origin of the "under-Lyne" element is less clear: it could derive from the British lemo meaning elm, or refer to Ashton being "under the line" of the Pennines.[3][4] This means that Ashton probably became a settlement some time after the Romans left Britain in the 5th century.[15] An early form of the town's name, which included a burh element, indicates that in the 11th century Ashton and Bury were two of the most important towns in Lancashire.[16] The "under Lyne" suffix was not widely used until the mid-19th century when it became useful for distinguishing the town from other places called Ashton.[17]

The Domesday Survey of 1086 does not directly mention Ashton, perhaps because only a partial survey of the area had been taken.[18][19] However, it is thought that St Michael's Church, mentioned in the Domesday entry for the ancient parish of Manchester, was in Ashton (also spelt Asheton, Asshton and Assheton).[20] The town itself was first mentioned in the 12th century when the manor was part of the barony of Manchester.[18] By the late 12th century, a family who adopted the name Assheton held the manor on behalf of the Gresleys, barons of Manchester.[21] Ashton Old Hall was a manor house, the administrative centre of the manor, and the seat of the de Ashton or de Assheton family.[22] With three wings, the hall was "one of the finest great houses in the North West" of the 14th century.[22] It has been recognised as important for being one of the few great houses in south-east Lancashire and possibly one of the few halls influenced by French design in the country.[22] The town was granted a Royal Charter in 1414, which allowed it to hold a fair twice a year, and a market on every Monday,[23][24] making the settlement a market town.[25]

According to popular tradition, Sir Ralph de Assheton, who was lord of the manor in the mid-14th century and known as the Black Knight, was an unpopular and cruel feudal lord. After his death, his unpopularity led the locals to parade an effigy of him around the town each Easter Monday and collect money.[26] Afterwards the effigy would be hung up, shot, and set on fire, before being torn apart and thrown into the crowd.[27] The first recorded occurrence of the event was in 1795, although the tradition may be older;[28] it continued into the 1830s.[29]

The manor remained in the possession of the Assheton family until 1514 when their male line ended. The lordship of the manor passed to Sir George Booth, great-great grandson of Sir Thomas Ashton,[20] devolving through the Booth family until the Earls of Stamford inherited it through marriage in 1758. The Booth-Greys then held the manor until the 19th century;[30] their patronage, despite being absentee lords, was probably the stimulus for Ashton's growth of a large-scale domestic-based textile industry in the 17th century.[31] Pre-industrial Ashton was centred on four roads: Town Street, Crickets Lane, Old Street, and Cowhill Lane. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the town was re-planned, with a grid pattern of roads. As a result, very little remains of the previous town.[25] In 1730 a workhouse was established which consisted of a house and two cottages; it later came to be used as a hospital.[32] The Ashton Canal was constructed in the 1790s to transport coal from the area to Manchester, with a branch to the coal pits at Fairbottom.[33]

Domestic fustian and woollen weaving have a long history in the town, dating back to at least the Early Modern period. Accounts dated 1626 highlight that Humphrey Chetham had dealings with clothworkers in Ashton.[34] However, the introduction of the factory system in the 19th century, during the Industrial Revolution, changed Ashton from a market town to a mill town. Having previously been one of the two main towns in the Tame Valley, Ashton-under-Lyne became one of the "most famous mill towns in the North West".[35] On Christmas Day 1826, workers in the town formed the Ashton Unity, a sickness and benefits society that was later renamed the Loyal Order of Ancient Shepherds. From 1773 to 1905, 75 cotton mills were established in the town. On his tour of northern England in 1849, Scottish publisher Angus Reach said:

In Ashton, too, there lingers on a handful of miserable old men, the remnants of the cotton hand-loom weavers. No young persons think of pursuing such an occupation. The few who practice it were too old and confirmed in old habits, when the power-loom was introduced, to be able to learn a new way of making their bread.[36]

— Angus Reach, Morning Chronicle, 1849

The cotton industry in the area grew rapidly from the start of the 19th century until the Lancashire Cotton Famine of 1861–1865.[37] The growth of the town's textile industry led to the construction of estates specifically for workers. Workers' housing in Park Bridge, on the border between Ashton and Oldham, was created in the 1820s.[38] The iron works were founded in 1786 and were some of the earliest in the north west.[39] The Oxford Mills settlement was founded in 1845 by the local industrialist and mill-owner Hugh Mason[40] who saw it as a model industrial community.[17] The community was provided with a recreational ground, a gymnasium, and an institute containing public baths, a library, and a reading room.[41] Mason estimated that establishing the settlement cost him around £10,000 and would require a further £1,000 a year to maintain (about £600,000 and £60,000 respectively as of 2020), and that its annual mortality rate was significantly lower than in the rest of the town.[42][43]

A poor supply of fresh water and dwellings without adequate drainage led to a cholera outbreak in the town in 1832.[44] The Ashton Poor Law Union was established in 1837 and covered most of what is now Tameside. A new workhouse was built in 1850 which provided housing for 500 people. It later became part of Tameside General Hospital.[32] Construction on the Sheffield, Ashton-under-Lyne and Manchester Railway (SA&MR) began in 1837 to provide passenger transport between Manchester and Sheffield. Although a nine-arch viaduct in Ashton collapsed in April 1845, the line was fully opened on 22 December 1845. The SA&MR was amalgamated with the Sheffield and Lincolnshire Junction Railway, the Great Grimsby & Sheffield Railway, and the Grimsby Docks Company in 1847 to form the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway (MS&LR).[45] In 1890, the MS&LR bought the Old Hall and demolished it to make way for the construction of new sidings.[22]

In the late 19th century, public buildings such as the market hall, town hall, public library, and public baths were built.[40] A donation from Hugh Mason funded the construction of the baths built in 1870–1871.[46] The Ashton-under-Lyne Improvement Act was passed in 1886 which gave the borough influence over housing and allowed the imposition of minimum standards such as drainage.[47] Coal mining was not as important to the town as the textile industry, but in 1882 the Ashton Moss Colliery had the deepest mine shaft in the world at 870 metres (2,850 ft).[48] Ashton's textile industry remained constant between 1865 and the 1920s. Although some mills closed or merged, the number of spindles in use increased.[37][49] With the collapse of the overseas market in the 1920s, the town's cotton industry went into decline, and by the 1930s most of the firms and mills in the area had closed.[37]

At about 4.20 pm on Wednesday 13 June 1917, a fire in an ammunition factory producing TNT caused an explosion that demolished much of the west end of the town. Two gasometers exploded and the explosion destroyed the factory and threw heavy objects long distances. At least 41 people died and about 100 were injured. Sylvain Dreyfus, managing director of the works, helped to fight the fire but died in the subsequent explosion.[50]

The second of the five victims of the Moors murders, 12-year-old John Kilbride, was lured away from the town's market on 23 November 1963 by Ian Brady and Myra Hindley before being murdered and buried on Saddleworth Moor. His body was found in October 1965.

Ashton became a part of the newly formed Metropolitan Borough of Tameside in 1974.[51] In May 2004, a huge fire ravaged the Victorian market hall, and a temporary building called "The Phoenix Market Hall" was built on Old Cross Street on the opposite side of the Old Market hall.[52] Described as the "heart of Ashton", the market was rebuilt and officially opened on 1 December 2008.[53]

Governance

Lying within the historic county boundaries of Lancashire since the early 12th century, Ashton anciently constituted a "single parish-township", but was divided into four divisions (sometimes each styled townships): Ashton Town, Audenshaw, Hartshead, and Knott Lanes.[1][54][55] Ashton Town was granted a Royal Charter in 1414, giving it the right to hold a market. All four divisions lay within the Hundred of Salford, an ancient division of the county of Lancashire.[1]

In 1827, police commissioners were established for Ashton Town, tasked with bringing about social and economic improvement.[1] In 1847, this area was incorporated under the Municipal Corporations Act 1835, as a municipal borough with the name "Ashton-under-Lyne", giving it borough status.[1][56] When the administrative county of Lancashire was created by the Local Government Act 1888, the borough fell under the newly created Lancashire County Council.[1] The borough's boundaries changed during the late 19th century through small exchanges of land with the neighbouring districts of Oldham, Mossley, Dukinfield, and Stalybridge.[1] In the early 20th century, the Borough of Ashton-under-Lyne grew; Hurst Urban District was added in 1927, parts of Hartshead and Alt civil parishes in 1935, and parts of Limehurst Rural District in 1954. Since 1956, Ashton has been twinned with Chaumont, France.[57]

Under the Local Government Act 1972, the town's borough status was abolished, and Ashton has, since 1 April 1974, formed part of the Metropolitan Borough of Tameside, within the metropolitan county of Greater Manchester.[1] Ashton-under-Lyne is divided into four wards: Ashton Hurst, Ashton St. Michaels, Ashton St Peters, and Ashton Waterloo. After the 2012 local elections, all twelve seats were held by Labour councillors.[58]

Since the Reform Act 1832 the town has been represented in Parliament as part of the Ashton-under-Lyne parliamentary constituency. During its early years the constituency was represented in the House of Commons by members of the Liberal Party until the late 19th century, when it was broadly held by the Conservative Party. It has been held by the Labour Party since 1935; Angela Rayner has been the constituency's Member of Parliament since 2015.[59]

Geography

.jpg)

At 53°29′38″N 2°6′11″W (53.4941°, −2.1032°), and 160 miles (257 km) north-northwest of London, Ashton-under-Lyne stands on the north bank of the River Tame, about 35 feet (11 m) above the river.[3] Described in Samuel Lewis's A Topographical Dictionary of England (1848) as situated "on a gentle declivity",[3] Ashton-under-Lyne lies on undulating ground by the Pennines, reaching a maximum elevation of about 1,000 feet (305 m) above sea level. It is 6.2 miles (10.0 km) east of Manchester city centre, and is bound on all sides by other towns: Audenshaw, Droylsden, Dukinfield, Mossley, Oldham, and Stalybridge, with little or no green space between them. Ashton experiences a temperate maritime climate, like much of the British Isles.

Generally the bedrock of the west of the town consists of coal measures, which were exploited by the coal mining industry, while the east is mainly millstone grit. Overlying the bedrock are deposits of glacial sand and gravel, clay, and some alluvial deposits. Ashton Moss, a peat bog, lies to the west of the town and was originally much larger.[60] The River Tame forms part of the southern boundary, dividing the town from Stalybridge and Dukinfield, and the River Medlock runs to the west.

Ashton's built environment is similar to the urban structure of most towns in England, consisting of residential dwellings centred on a market square and high street in the town centre, which is the local centre of commerce. There is a mixture of low-density urban areas, suburbs, semi-rural and rural locations in Ashton-under-Lyne, but overwhelmingly the land use in the town is residential; industrial areas and terraced houses give way to suburbs and rural greenery as the land rises out of the town in the east. The older streets are narrow and irregular, but those built more recently are spacious, lined by "substantial and handsome houses".[3] Areas and suburbs of Ashton-under-Lyne include Cockbrook, Crowhill, Guide Bridge, Hartshead, Hazelhurst, Hurst, Limehurst, Ryecroft, Taunton, and Waterloo.[54]

Demography

| Ashton-under-Lyne compared | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 UK census | Ashton-under-Lyne[61] | Tameside[62] | England |

| Total population | 43,236 | 213,043 | 49,138,831 |

| White | 82.3% | 91.2% | 91% |

| Asian | 11.2% | 5.6% | 4.6% |

| Black | 0.3% | 1.2% | 2.3% |

As of the 2001 UK census, Ashton-under-Lyne had a population of 43,236.[63] The 2001 population density was 12,374 per mi² (4,777 per km²), with a 100 to 96.1 female-to-male ratio.[64] Of those over 16 years old, 30.9% were single (never married) and 50.0% married.[65] Ashton-under-Lyne's 18,347 households included 33.2% single people, 33.0% married couples living together, 8.9% co-habiting couples, and 12.4% single parents with their children; these figures were similar to those of Tameside, however both Tameside and Ashton have higher rates of single-parent households than England (9.5%).[66] Of those aged 16–74, 37.0% had no academic qualifications, similar to the figure of 35.2% for all of Tameside but significantly higher than the 28.9% figure for all of England,[62][67] and 12% had an educational qualification such as first degree, higher degree, qualified teacher status, qualified medical doctor, qualified dentist, qualified nurse, midwife, health visitor, or similar, compared with 20% nationwide.[62][68]

In 1931, 10% of Ashton's population was middle class compared with 14% in England and Wales, and by 1971, this had increased steadily to 17% compared with 24% nationally. In the same time frame, there was a decline in the working-class population. In 1931, 34% were working class compared with 36% in England and Wales; by 1971, this had decreased to 29% in Ashton and 26% nationwide. The rest of the population was made up of clerical workers and skilled manual workers.[69]

Population change

In 1700, the population of Ashton, the Tame Valley's main urban area, was an estimated 550. The town's 18th-century growth was fuelled by an influx of people from the countryside attracted by the prospect of work in its new industries, mirroring the rest of the region.[70] In the early 19th century, Irish immigrants escaping from the Great Irish Famine were also drawn to the area by the new jobs created.[71][72] The availability of jobs created by the growth of the textile industry in the town led to Ashton's population increasing by more than 400% between 1801 and 1861, from 6,500 to 34,886. The population dropped by 9% during the 1860s as a consequence of the cotton famine caused by the American Civil War.[73] The table below details the population change since 1851, including the percentage change since the previous census.

| Population growth in Ashton-under-Lyne since 1851 | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1851 | 1861 | 1871 | 1881 | 1891 | 1901 | 1911 | 1921 | 1931 | 1939 | 1951 | 1961 | 1971 | 1991 | 2001 |

| Population | 29,790 | 34,886 | 31,984 | 36,399 | 40,486 | 43,890 | 45,172 | 43,335 | 51,573 | 46,534 | 46,794 | 50,154 | 48,974 | 44,385 | 43,263 |

| % change | – | +17.1 | −8.3 | +13.8 | +11.2 | +8.4 | +2.9 | −4.1 | +19.0 | −9.8 | +0.6 | +7.2 | −2.4 | −9.4 | −2.5 |

| Source:A Vision of Britain through Time[74][75] | |||||||||||||||

Religion

St Michael and All Angels' Church is a Grade I listed building that dates back to at least 1262, although it was rebuilt in the 15th, 16th, and 19th centuries.[76] In 1795 it was the only church in the town, and one of only two in Tameside. There was a great increase in the number of chapels and religious buildings in the area during the 19th century, and by the end of the century there were 44 Anglican churches and 138 chapels belonging to other denominations. The most common denominations amongst the chapels were Catholic, Congregationalist, and Methodist.[77]

The 19th-century evangelist John Wroe attempted to turn Ashton-under-Lyne into a "new Jerusalem". He founded the Christian Israelite Church, and from 1822 to 1831 Ashton-under-Lyne was the religion's headquarters. Wroe intended to build a wall around the town with four gateways, and although the wall was never constructed, the four gatehouses were. Popular opinion in the town turned against Wroe when he was accused of indecent behaviour in 1831, but the charges were dismissed. The Church spread to Australia, where it is still active.[78][79]

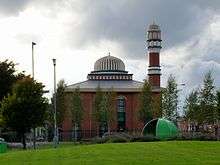

As of the 2001 UK census, 68.5% of Ashton residents reported themselves as being Christian, 6.1% Muslim, 5.0% Hindu, and 0.2% Buddhist. The census recorded that 11.4% had no religion, 0.2% had an alternative religion, and 8.7% did not state their religion.[80] The proportion of Hindus in the town was much higher than the average for the borough and the whole of England (1.4% and 1.1% respectively). The percentage of Muslims in Ashton-under-Lyne was nearly double the national average of 3.1%, and was higher than the average of 2.5% for Tameside.[81] As of October 2013, six mosques were located in the town,[82] including one on Hillgate Street in Penny Meadow (Ashton Central Mosque, formerly known as Markazi Jamia Mosque)[83] and one on Katherine Street in West End (Masjid Hamza Mosque).

Economy

| Ashton-under-Lyne compared | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 UK Census | Ashton-under-Lyne[84] | Tameside[85] | England |

| Population of working age | 30,579 | 152,313 | 35,532,091 |

| Full-time employment | 41.0% | 43.5% | 40.8% |

| Part-time employment | 11.3% | 11.5% | 11.8% |

| Self employed | 5.9% | 6.5% | 8.3% |

| Unemployed | 4.1% | 3.3% | 3.3% |

| Retired | 12.2% | 13.3% | 13.5% |

In the medieval period, farming was important in Ashton, particularly arable farming.[86] By the 18th century, textiles had also become important to the town's economy; in the 1700s, 33% of those with jobs worked in textiles and 36% in agriculture.[87] With the advent of the Industrial Revolution in the second half of the 18th century, the textile industry in the town boomed. It continued to expand until the cotton famine of 1861–1865, after which the industry remained steady until it collapsed after the overseas markets shut down in the 1920s.[88]

Coal has been mined in Ashton since at least the 17th century.[89] In the late 18th and early 19th centuries demand for coal increased, which led to an expansion of the town's coal industry. The produce of the collieries was transported by canal to Manchester.[48] The industry began to decline during the late 19th century, and by 1904 only the Ashton Moss Colliery was still operational, the last colliery to be opened in the area.[48]

Ashton town centre, which is the largest in Tameside, developed in the Victorian period. Many of the original buildings have survived, and as a result, the town centre is protected by Tameside Council as a conservation area.[24][90] As well as being populated by leading high-street names, Ashton has an outdoor market which was established in the medieval period. It is made up of about 180 stalls, and is open six days a week.[24] The farmers' market, with over 70 stalls, is the largest in the region, as is the weekday flea market.[91] Ashton Market Hall underwent a £15 million restoration after it was damaged by fire. The Ashton Renewal Area project has attracted investment in the town centre, encouraging conservation and economic development.[24]

The 140,000-square-foot (13,000 m2), two-floored Ashton Arcades shopping centre opened in 1995; permission has been granted for a £40 million extension but work on this project has yet to begin. In 2006, after failing twice to gain permission, IKEA announced plans to build its first town-centre store in Ashton-under-Lyne. The store was expected to create 500 new jobs and to attract other businesses to the area.[92] The store opened on 19 October 2006 and covers 296,000 square feet (27,500 m2). At the time of its creation, the store was the tallest in Britain.[93]

Amongst the facilities provided by Ashton Leisure Park are a 14-screen cinema, a bowling alley, and several restaurants.[94] The St Petersfield area of Ashton underwent a £42 million redevelopment and provided 2,000 jobs. The aim of the investment was to create a business district in the town and bring life to a neglected area of Ashton. The development provided 280,000 square feet (26,000 m2) of office space and 400,000 square feet (37,000 m2) of retail and leisure space.[95] Pennine Care NHS Trust relocated its headquarters to the St Petersfield area in 2006.[96] Until then a popular nightspot, in 2002 several night clubs were brought to the brink of closure after a downturn in trade caused by four murders in three months.[97]

According to the 2001 UK census, residents aged 16–74 were employed in the following industries: 22.7% manufacturing, 18.6% retail and wholesale, 11.3% health and social work, 9.8% property and business services, 6.7% construction, 6.5% transport and communications, 5.8% education, 5.6% public administration, 4.3% hotels and restaurants, 3.8% finance, 0.4% agriculture, 0.7% energy and water supply, and 3.9% other. Compared with national figures, the town had a relatively low percentage working in agriculture, public administration, and property, and high rates of employment in construction, at more than triple the national rate (6.8%).[98] The census recorded the economic activity of residents aged 16–74; 2.0% were students with jobs, 3.8% students without jobs, 6.4% looking after home or family, 9.5% permanently sick or disabled, and 3.9% economically inactive for other reasons.[84] Ashton's 4.1% unemployment rate was above the national rate of 3.3%.[85]

Culture

Sports

The town's most prominent football teams are Ashton United F.C. and Curzon Ashton F.C. Ashton United was the first team in the Manchester Football Association to win an FA Cup tie, when they beat Turton 3–0 in 1883. In 1885, they were the first winners of the Manchester Senior Cup, beating Newton Heath (who later became Manchester United) in the final.[99] They currently compete in the Northern Premier League Premier Division, the seventh tier of English football, playing at Hurst Cross. Curzon Ashton has competed since 2015 in the National League North, the highest level in the club's history; they play at the Tameside Stadium. Other sporting venues include the Richmond Park Athletics Stadium, which has an all-weather running track with facilities for field events[100] and is home to the East Cheshire Harriers, Tameside Athletics Club, and Ashton Cricket Club, which has won the Central Lancashire Cricket League's first and second division twice each, and the Wood Cup four times.[101]

Landmarks

After the Ashton Canal closed in the 1960s, it was decided to turn the Portland Basin warehouse into a museum. In 1985, the first part of the Heritage Centre and Museum opened on the first floor of the warehouse.[102] The restoration of the building was complete in 1999; the museum details Tameside's social, industrial, and political history.[103] The basin next to the warehouse is the point at which the Ashton Canal, the Huddersfield Narrow Canal and the Peak Forest Canal meet. It has been used several times as a filming location for Coronation Street, including a scene where the character Richard Hillman drove into the canal.[104]

The earliest parts of Ashton Town Hall, which was the first purpose-built town hall in what is now Tameside, date to 1840 when it was opened. It has classical features such as the Corinthian columns on the entrance facade. Enlarged in 1878, the hall provides areas for administrative purposes and public functions.[105] The Old Street drill hall was completed in 1887.[106]

There are five parks in the town, three of which have Green Flag Awards.[107] The first park opened in Ashton-under-Lyne was Stamford Park on the border with Stalybridge. The park opened in 1873, after a 17-year campaign by local cotton workers;[108] the land was bought from a local mill-owner for £15,000 (£1.4 million as of 2020)[109] and further land was donated by George Grey, 7th Earl of Stamford.[110] A crowd of between 60,000 and 80,000 turned out to see the Earl of Stamford formally open the new facility on 12 July 1873. It now includes a boating lake, and a memorial to Joseph Rayner Stephens, commissioned by local factory workers to commemorate his work promoting fair wages and improved working conditions. A conservatory was opened in 1907, and Coronation gates were installed at both the Ashton-under-Lyne and Stalybridge entrances in 1953.[108]

.jpg)

Hartshead Pike is a stone tower on top of Hartshead Hill overlooking Ashton and Oldham.[111] The existing building was constructed in 1863 but there has been a building on the site since at least the mid-18th century, although the original purpose is obscure. The pike might have been the site of a beacon in the late 16th century.[112] It has a visitor centre and from the top of the hill it is possible to see the Jodrell Bank Observatory in Cheshire, the Welsh hills, and the Holme Moss transmitter in West Yorkshire.[113]

.jpg)

The Witchwood public house, in the St Petersfield area of the town, has been a music venue since the 1960s, hosting acts such as Muse, The Coral, and Lost Prophets.[114] In 2004 The Witchwood came under threat when the area was being redeveloped, but was saved from demolition after a campaign by locals and led by Tom Hingley, drawing support from musicians such as Bert Jansch, The Fall, and The Chameleons.[115]

The main Ashton-under-Lyne War Memorial, in Memorial Gardens, consists of a central cenotaph on a plinth, surmounted by a sculpted wounded soldier and the figure of "Peace who is taking the sword of honour" from his hand.[116] It commemorates the 1,512 people from the town who died in the First World War and the 301 who died in the Second World War.[117] The cenotaph is flanked on both sides by bronze lions. The plinth is decorated with military equipment representing the services, as well as bronze tablets listing the Roll of Honour from World War I. Commissioned by the Ashton War Memorial Committee, the statue was sculpted between 1919 and 1922 by John Ashton Floyd, and unveiled on 16 September 1922 by General Sir Ian Hamilton.[116]

The tablet on the front of the memorial reads:

1914–1919[116]

Transport

Roads

In 1732, an Act of Parliament was passed which permitted the construction of a turnpike from Manchester, then in Lancashire, to Salters Brook in Cheshire. The road passed through Ashton-under-Lyne as well as Audenshaw, Mottram-in-Longdendale, and Stalybridge. A Turnpike Trust was responsible for collecting tolls from traffic; the proceeds were used for road maintenance. The Trust for Manchester to Salters Brook was one of over 400 established between 1706 and 1750, a period in which turnpikes became popular.[118] It was the first turnpike to be opened in Tameside, and driven by economic growth, more turnpikes were opened in the area in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Acts of Parliaments were passed in 1765, 1793, and 1799 permitting the construction of turnpikes from Ashton-under-Lyne to Doctor Lane Head in Saddleworth, Standedge in Saddleworth, and Oldham respectively. Towards the end of the 19th century, many Turnpike Trusts were wound up as they were superseded by local government; the last in Tameside to close was the Ashton-under-Lyne to Salters Brook road in 1884.[119] Ashton is now served by the M60 motorway, which cuts through the west end of Ashton (Junction 23).

Canals

The town of Ashton-under-Lyne became the focus of three canals which were constructed in Tameside in the 1790s because it was an important centre of coal mining in the Lancashire coalfield. The 1790s has been characterised as a period of mania for canal building in England. The first of the three to be built was the Ashton Canal, which was constructed between 1792 and 1797. Connecting Manchester to Ashton-under-Lyne, with a branch to Oldham, it cost about £170,000 (£17 million as of 2020).[109][120] The Peak Forest Canal was constructed from 1794 to 1805, and was originally planned as a branch of the Ashton Canal. It connected the Portland Basin with the Peak District and cost £177,000 (£14 million as of 2020).[109][121] The Huddersfield Narrow Canal was built between 1794 and 1811, to enable cross-Pennine trade between Manchester and Kingston upon Hull; the cost of construction was £400,000.[109][121]

The advent of the railways in the 19th century signalled the decline of the canal system. The new railways were quicker and more economical than the canals, and the waterways declined. The Huddersfield Canal was bought by the Huddersfield and Manchester Railway in 1844. Along with the Ashton and Peak Forest canals, the Huddersfield Canal was later bought by the Sheffield, Ashton-under-Lyne and Manchester Railway Company.[122] The canals remained in use throughout the 19th century on a smaller scale than in their heyday, but by the mid-20th century all commercial traffic had ceased. Following an extended period of closure and dereliction, during which parts of the Huddersfield Canal were filled in or built over, a complete restoration was undertaken and the entire canal reopened in 2001. The three canals are now used for leisure craft and are still maintained and in good condition.[123]

Railways

The present station at Ashton was opened by the Ashton, Stalybridge and Liverpool Junction Railway (AS&LJR) on 13 April 1846.[124][125] Known originally as Ashton, it was renamed Ashton (Charlestown) in 1874.[124] and then Ashton-under-Lyne on 6 May 1968.[124] It has regular services on the Huddersfield Line between Manchester (Victoria) and Huddersfield.

The town historically had three stations, only one of which remains: Ashton (Charlestown), Park Parade (closed 1956) and Oldham Road (closed 1959). Park Parade station was on the Sheffield, Ashton-under-Lyne and Manchester Railway, which was founded in 1836 with the purpose of building a line linking Manchester and Sheffield. The line was opened in stages and by 1845 was complete. It included a branch to the nearby town of Stalybridge, the former Ashton Park Parade station was included on this branch.[45]. Oldham Road station was on the Oldham, Ashton and Guide Bridge Railway. Additionally, Guide Bridge station, a few miles away, was known as Ashton & Hooley Hill and then Ashton in its earliest years.

Trams and buses

In 1881, a tramway with horse-drawn tramcars was opened between Stalybridge and Audenshaw, through Ashton-under-Lyne. The first tramway of its kind in Tameside, it was later extended to Manchester. The Oldham, Ashton and Hyde Electric Tramway Company, founded in 1899, operated 13 km (8 mi) of tram lines with electric tramcars. It was the first line around Manchester to use electricity. A line from Stalybridge to Ashton-under-Lyne was opened in 1903 and operated by the Stalybridge, Hyde, Mossley & Dukinfield Tramways & Electricity Board.[126] The first bus service from Ashton-under-Lyne ran in 1923 and the 1920s saw a period of decline for the tramways as they suffered from the competition with buses. The last of the first generation of electric tram services in the town ran in 1938.[127]

After a 75-year absence, trams returned to Ashton in October 2013, when the Manchester Metrolink tram system opened the East Manchester Line to the town: Ashton-under-Lyne tram stop in the town centre stands alongside the bus station and is the terminus for the East Manchester Line, which runs to Manchester Piccadilly station and Manchester city centre. Away from the town centre towards Manchester there are also the Ashton West and Ashton Moss tram stops.[128]

Education

There are ten nursery schools,[129] sixteen primary schools,[130] and two secondary schools in Ashton-under-Lyne as of 2019.[131] In 2006, the council began a scheme to develop education in the borough by opening six new secondary schools. Among the changes proposed as part of the £160 million scheme was the closure of Hartshead Sports College and Stamford Community High School, to be replaced by a 1,350-pupil academy with 300 sixth-form members. In 2007, Hartshead Sports College was placed on "special measures" after it failed to achieve its targets for General Certificate of Secondary Education results and was criticised by Ofsted for its teaching standard.[132] The new academy opened in September 2008,[133] a year ahead of schedule.[134] It was named New Charter Academy (now Great Academy Ashton) after its sponsor, the New Charter Housing Trust.

The other secondary school in the town is St Damian's RC Science College, which was founded in 1963, and provides education for 800 pupils aged 11–16.[135] As part of the Building Schools for the Future project, a replacement school building was built by Carillion and opened in May 2011. Dale Grove School has 60 pupils and offers education for pupils aged 5–16 with special needs.[136] Ashton Sixth Form College is a centre for further education with 1,650 pupils aged 16–18.[137] Tameside College also provides opportunities for further education and operates in Ashton-under-Lyne, Droylsden, and Hyde.[138] Founded in 1954 and expanded in 1957 and 1964, it was originally called Ashton College.[139]

Public services

In the early 19th century, Ashton-under-Lyne's growth made it necessary to find a new water supply. Before the introduction of piped water the town's inhabitants drew water from wells and the nearby River Tame. Industrial processes had, however, polluted the river and the wells could not sustain a rapidly expanding population. From 1825, a private company was responsible for piping water from reservoirs, but there were still many homes without proper drainage or water supply.[44] Waste management is now co-ordinated by the local authority via the Greater Manchester Waste Disposal Authority.[140] The first power station in Tameside was built in 1899, providing power for the area.[141] Ashton's Distribution Network Operator for electricity is United Utilities;[142] there are no power stations in the town. United Utilities also manages the drinking and waste water.[142]

Home Office policing in Ashton-under-Lyne is provided by the Greater Manchester Police. The force's Tameside Division have their divisional headquarters for policing Tameside in the town.[143][144] Public transport in the area is co-ordinated by Transport for Greater Manchester. Statutory emergency fire and rescue service is provided by the Greater Manchester Fire and Rescue Service, which has one station on Slate Lane.[145] The Tameside General Hospital is a large NHS hospital on the outskirts of the town,[146] administered by Tameside & Glossop Integrated Care NHS Foundation Trust.[147] The North West Ambulance Service provides emergency patient transport.

See also

References

Notes

- Greater Manchester Gazetteer, Greater Manchester County Record Office, Places names – A, archived from the original on 18 July 2011, retrieved 20 September 2008

- "2011 census". Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- Lewis (1848) pp. 90–96.

- Wilson (1870–1872).

- Greater Manchester Police (25 January 2006), Ashton, gmp.police.uk, archived from the original on 1 November 2007, retrieved 19 September 2008

- Nevell (1992), p. 25.

- Nevell (1992), p. 11.

- Nevell (1992), p. 30.

- Nevell (1992), p. 71.

- Hodgson & Brennand (2004), p. 44.

- Nevell and Walker (1998), pp. 40–41.

- Nevell (1992), pp. 77–83.

- Nevell (1997), p. 32.

- University of Nottingham's Institute for Name-Studies, Ashton-under-Lyne, nottingham.ac.uk, retrieved 18 September 2008

- Nevell (1992), pp. 84–85.

- Nevell (1992), p. 88.

- Township Information – Ashton, Tameside.gov.uk, archived from the original on 16 September 2008, retrieved 12 September 2008

- Nevell (1991), p. 17.

- Redhead, Norman, in: Hartwell, Hyde and Pevsner (2004), p. 18.

- "The parish of Ashton-under-Lyne: Introduction, manor & boroughs". A History of the County of Lancaster: Volume 4. 1911. pp. 338–347. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- Nevell and Walker (1998), p. 47.

- Nevell and Walker (1998), p. 54.

- Nevell (1991), p. 60.

- Ashton-under-Lyne town centre, Tameside.gov.uk, archived from the original on 4 January 2009, retrieved 13 September 2008

- Nevell (1993), p. 146.

- Griffith (1898), p. 380.

- Griffith (1898), p. 381.

- The Black Knight Pageant, Ashton-under-Lyne.com, archived from the original on 3 October 2008, retrieved 20 September 2008

- Griffith (1898), pp. 379, 382.

- Nevell and Walker (1998), p. 48.

- McNeil & Nevell (2000), p. 54.

- Burke and Nevell (1996), p. 123.

- Nevell (1993), p. 99.

- Frangopulo (1977), p. 25.

- McNiel and Nevell (2005), p. 54.

- Powell (1986), p. 35.

- Nevell (1993), p. 35.

- Nevell and Walker (1999), p. 49.

- Nevell and Roberts (2003), pp. 19, 22, 31–32.

- Nevell (1993), p. 151.

- Nevell (1993), p. 152.

- Nevell (1994), pp. 44–45.

- Currency converter, NationalArchives.gov.uk, archived from the original on 5 September 2008, retrieved 12 September 2008

- Nevell (1993), p. 132.

- Nevell (1993), p. 127.

- Nevell (1993), p 23.

- Nevell (1993), pp. 149–151.

- Nevell (1993), p. 102.

- Nevell (1993), p. 37.

- Daily Telegraph Friday 15 June 1917, reprinted in Daily Telegraph Thursday 15 June 2017 page 28

- Nevell (1993), p. iii.

- Sue Carr (21 October 2004), "Ashton celebrates as new market opens its doors", Tameside Advertiser, archived from the original on 21 August 2008, retrieved 18 September 2008

- Sue Carr (1 December 2008), "Joy as market hall opens", Tameside Advertiser, archived from the original on 22 December 2008, retrieved 10 July 2009

- Farrer & Brownbill (1911), pp. 338–347.

- A vision of Ashton under Lyne AP/CP, visionofbritain.org.uk, archived from the original on 3 November 2012, retrieved 19 September 2008

- A vision of Britain through time, A vision of Ashton under Lyne MB, archived from the original on 30 September 2007, retrieved 3 June 2007

- Tameside Metropolitan Borough Council (27 September 2006), Town twinning, Tameside.gov.uk, archived from the original on 20 August 2008, retrieved 4 September 2008

- Tameside Metropolitan Borough Council, Know you councillor, Tameside.gov.uk, archived from the original on 12 July 2012, retrieved 8 May 2012

- "Ashton under Lyne", The Guardian, archived from the original on 18 December 2014, retrieved 8 September 2010

- Nevell (1992), pp. 10–11.

- "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS06 Ethnic group

- Tameside Metropolitan Borough key statistics, Statistics.gov.uk, archived from the original on 26 May 2011, retrieved 12 September 2008

- Tameside Census Snapshot (PDF), Tameside MBC, 2004, archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2008, retrieved 17 January 2008

- "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS01 Usual resident population

- "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS04 Marital status

- KS20 Household composition: Census 2001, Key Statistics for urban areas, Statistics.gov.uk, 2 February 2005, archived from the original on 29 June 2011, retrieved 12 September 2008

•Tameside Metropolitan Borough household data, Statistics.gov.uk, archived from the original on 4 June 2011, retrieved 12 September 2008 - "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS13 Qualifications and students

- "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS13 Qualifications and students

- Ashton under Lyne social class, Vision of Britain, archived from the original on 3 November 2012, retrieved 15 September 2008

•Percentage of Working-Age Males in Class 1 and 2, Vision of Britain, retrieved 15 September 2008

•Percentage of Working-Age Males in Class 4 and 5, Vision of Britain, retrieved 15 September 2008 - Nevell (1993), p. 168.

- Nevell (1993), p. 27.

- The Murphy Riots in Ashton under Lyne, Ashton-under-Lyne.com, archived from the original on 3 May 2008, retrieved 9 December 2007

- Nevell (1993), p. 36.

- Facts about Ashton, Tameside.gov.uk, archived from the original on 4 July 2008, retrieved 16 September 2008

- Nevell (1993), p. 12.

- Nevell (1991), pp. 121, 135.

- Nevell (1993), p. 142.

- Nevell (1994), p. 95.

- A Tribute to Prophet Wroe 1782–1863, Tameside.gov.uk, archived from the original on 30 June 2009, retrieved 10 July 2009

- "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS07 Religion

- Tameside Metropolitan Borough key statistics, Statistics.gov.uk, archived from the original on 3 May 2009, retrieved 10 July 2009

- "List of mosques in Ashton-under-Lyne". Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- Markazi Jamia Mosque, Yell.com, archived from the original on 27 September 2011, retrieved 10 July 2009

- "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS09a Economic activity – all people

- Tameside Local Authority economic activity, Statistics.gov.uk, archived from the original on 4 June 2011, retrieved 15 September 2008

- Nevell (1991), p. 52.

- Nevell (1993), pp. 35, 83.

- Nevell (1993), pp. 35–39

- Nevell (1993), p. 101.

- Tameside Metropolitan Borough Council (November 1992), Appendix 6: Conservation Areas and Scheduled Ancient Monuments (Policies C11 and C30), Tameside.gov.uk, archived from the original on 2 May 2009, retrieved 4 September 2008

- Ashton market, Tameside.gov.uk, 3 November 2007, archived from the original on 13 September 2008, retrieved 20 September 2008

- Ikea's superstore plans approved, BBC Online, 11 January 2006, archived from the original on 26 December 2007, retrieved 3 September 2008

- Emma Unsworth (16 October 2006), "IKEA's finally here", Manchester Evening News, retrieved 3 September 2008

- Completed development, Ashton-Moss.com, archived from the original on 22 March 2007, retrieved 6 July 2009

- David Thame (23 May 2005), "The big spenders are in town!", Manchester Evening News, retrieved 15 September 2008

- David Thame (5 July 2005), "Ashton's eastern promise", Manchester Evening News, retrieved 15 September 2008

- "Street killings hit town's night spots", Tameside Advertiser, 23 May 2002, archived from the original on 11 September 2012, retrieved 20 August 2008

- "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS11a Industry of employment – all people

- James (2008), pp. 33–34.

- History of East Cheshire Harriers, East Cheshire Harriers, archived from the original on 16 May 2008, retrieved 19 July 2009

- Oldham Cricket Club: Wood Cup, OldhamCC.co.uk, archived from the original on 12 June 2008, retrieved 1 September 2008

- Nevell and Walker (2001), pp. 59, 61.

- Nevell and Walker (2001), pp. 63–64.

- "From far-flung Canada to Corrie", Manchester Evening News, 17 September 2008, archived from the original on 22 September 2008, retrieved 19 September 2008

- Burke and Nevell (1996), pp. 118–119.

- "Ashton campaigners in battle on to save the historic Armoury". Manchester Evening News. 14 January 2015. Archived from the original on 29 September 2017. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- Parks in Tameside: Tameside Parks Moving Forward, Tameside.gov.uk, archived from the original on 31 July 2009, retrieved 7 July 2009

- Tameside Metropolitan Borough council : Stamford Park : History Archived 15 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 12 September 2009

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Nevell (1993), p. 145.

- Wyke (2005), p. 357.

- Burke and Nevell (1996), pp. 144–145.

- Hartshead Pike, Tameside.gov.uk, 13 October 2006, archived from the original on 4 December 2008, retrieved 20 September 2008

- Sue Carr (15 November 2006), Save The Witchwood, TamesideAdvertiser.co.uk, archived from the original on 5 May 2013, retrieved 26 April 2008

- Don Frame (24 January 2005), "Party as stars' pub is saved", Manchester Evening News, retrieved 29 January 2008

- Public Monuments and Sculpture Association (16 June 2003), Ashton-under-Lyne War Memorial, pmsa.cch.kcl.ac.uk, archived from the original on 30 June 2009, retrieved 19 September 2008

- Ashton War Memorial, Tameside.gov.uk, archived from the original on 21 August 2008, retrieved 10 July 2009

- Nevell (1993), pp. 118–120.

- Nevell (1993), p. 121.

- Nevell (1993), pp. 121–122.

- Nevell (1993), p. 122.

- Nevell (1993), pp. 123–124.

- Nevell (1993), pp. 124–125.

- Butt, R.V.J. (1995). The Directory of Railway Stations. Yeovil: Patrick Stephens Ltd. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-85260-508-7. R508.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marshall, John (1969). The Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway, volume 1. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. pp. 61, 63. ISBN 978-0-7153-4352-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nevell (1993), p. 130.

- Nevell (1993), pp. 130–131.

- British Trams Online Archived 19 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine Metrolink arrives in Ashton-under-Lyne, G. Prior

- Nursery Schools List by Area, Tameside.gov.uk, retrieved 22 May 2019

- Primary Schools List by Area, Tameside.gov.uk, retrieved 22 May 2019

- High Schools List by Area, Tameside.gov.uk, retrieved 22 May 2019

- Eve Dugdale (7 February 2007), "School is labelled as 'inadequate'", Tameside Advertiser, retrieved 25 June 2009

- New Charter Academy admission arrangements 2010/2011, Tameside.gov.uk, archived from the original on 14 June 2011, retrieved 25 June 2009

- Adam Derbyshire (22 November 2006), "Six super schools in vision of future", Tameside Advertiser, archived from the original on 2 April 2009, retrieved 25 June 2009

- St Damian's RC Science College, Department for Children, Schools and Families, archived from the original on 20 October 2009, retrieved 29 June 2009

- Dale Grove School, Department for Children, Schools and Families, archived from the original on 1 August 2012, retrieved 29 June 2009

- Ashton-under-Lyne Sixth Form College, Department for Children, Schools and Families, archived from the original on 29 July 2012, retrieved 29 June 2009

- Find us – Tameside College, Tameside.ac.uk, archived from the original on 7 March 2009, retrieved 29 June 2009

- "Nostalgia: the 1950s", The Tameside Advertiser, 9 October 2003, archived from the original on 29 December 2007, retrieved 29 June 2009

- "Greater Manchester Waste Disposal Authority (GMWDA)". Greater Manchester Waste Disposal Authority. 2008. Archived from the original on 7 February 2008. Retrieved 8 February 2008.

- Nevell (1993), pp. 134–135.

- "Tameside". United Utilities. 17 April 2007. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- "Your Area – Tameside". Greater Manchester Police. 25 January 2006. Archived from the original on 1 November 2007. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- "Tameside". Greater Manchester Police. Archived from the original on 3 February 2010. Retrieved 6 July 2009.

- "Ashton-Under-Lyne Fire Station". Greater Manchester Fire and Rescue Service. Archived from the original on 8 June 2009. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- "Profile". Tameside Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- "About the Trust". Tameside Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

Bibliography

- Burke, Tom; Nevell, Mike (1996), Buildings of Tameside, Tameside Metropolitan Borough and University of Manchester Archaeological Unit, ISBN 978-1-871324-14-3

- Farrer, William; Brownbill, J (1911), The parish of Ashton-under-Lyne – Introduction, manor & boroughs, British-history.ac.uk

- Frangopulo, N. J. (1977), Tradition in Action: The Historical Evolution of the Greater Manchester County, Wakefield: EP, ISBN 978-0-7158-1203-7

- Griffith, Kate (1898), "The Black Lad of Ashton-under-Lyne", Folklore, Folklore Society, 8 (4): 379–382, doi:10.1080/0015587x.1898.9720476

- Hartwell, Clare; Hyde, Matthew; Pevsner, Nikolaus (2004), Lancashire : Manchester and the South-East, The buildings of England, New Haven, Conn.; London: Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-10583-4

- Hodgeson, John; Brennand, Mark (2004), Mark Brennand (ed.), The Prehistoric Period Resource Assessment, pp. 23–58, ISSN 0962-4201

- James, Gary (2008), Manchester – A Football History, Halifax: James Ward, ISBN 978-0-9558127-0-5

- Lewis, Samuel (1848), A Topographical Dictionary of England, Institute of Historical Research, ISBN 978-0-8063-1508-9

- McNeil, R & Nevell, M (2000), A Guide to the Industrial Archaeology of Greater Manchester, Association for Industrial Archaeology, ISBN 978-0-9528930-3-5

- Nevell, Mike (1991), Tameside 1066–1700, Tameside Metropolitan Borough and University of Manchester Archaeological Unit, ISBN 978-1-871324-02-0

- Nevell, Mike (1992), Tameside Before 1066, Tameside Metropolitan Borough and Greater Manchester Archaeological Unit, ISBN 978-1-871324-07-5

- Nevell, Mike (1993), Tameside 1700–1930, Tameside Metropolitan Borough and University of Manchester Archaeological Unit, ISBN 978-1-871324-08-2

- Nevell, Mike (1994), The People Who Made Tameside, Tameside Metropolitan Borough Council, ISBN 978-1-871324-12-9

- Nevell, Mike (1997), The Archaeology of Trafford, Trafford Metropolitan Borough Council with the University of Manchester Archaeological Unit, ISBN 978-1-870695-25-1

- Nevell, Mike; Roberts, John (2003), The Park Bridge Ironworks and the archaeology of the Wrought Iron Industry in North West England, 1600 to 1900, Tameside Metropolitan Borough with University of Manchester Archaeological Unit, ISBN 978-1-871324-27-3

- Nevell, Mike; Walker, John (1998), Lands and Lordships in Tameside, Tameside Metropolitan Borough Council with the University of Manchester Archaeological Unit, ISBN 978-1-871324-18-1

- Nevell, Mike; Walker, John (2001), Portland Basin and the archaeology of the Canal Warehouse, Tameside Metropolitan Borough with University of Manchester Archaeological Unit, ISBN 978-1-871324-25-9

- Powell, Rob (1986), In the Wake of King Cotton, Rochdale Art Gallery

- Wilson, John Marius (1870–1872), Imperial Gazetteer of England and Wales, A. Fullarton & Co

- Wyke, Terry (2005), Public Sculpture of Greater Manchester, Liverpool University Press, ISBN 978-0-85323-567-5

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Ashton-under-Lyne. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ashton-under-Lyne. |