Launceston Castle

Launceston Castle is located in the town of Launceston, Cornwall, England. It was probably built by Robert the Count of Mortain after 1068, and initially comprised an earthwork and timber castle with a large motte in one corner. Launceston Castle formed the administrative centre of the new earldom of Cornwall, with a large community packed within the walls of its bailey. It was rebuilt in stone in the 12th century and then substantially redeveloped by Richard of Cornwall after 1227, including a high tower to enable visitors to view his surrounding lands. When Richard's son, Edmund, inherited the castle, he moved the earldom's administration to Lostwithiel, triggering the castle's decline. By 1337, the castle was increasingly ruinous and used primarily as a gaol and to host judicial assizes.

| Launceston Castle | |

|---|---|

| Launceston, Cornwall | |

| |

Launceston Castle | |

| Coordinates | 50.63757°N 4.36144°W |

| Type | Castle |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Duchy of Cornwall |

| Controlled by | English Heritage |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Site history | |

| Materials | Shale |

| Events | Prayer Book Rebellion English Civil War |

The castle was captured by the rebels during the Prayer Book Rebellion of 1549, and was garrisoned by the Royalists during the English Civil War in the 17th century. Towards the end of the civil war it was stripped for its building materials and rendered largely uninhabitable. A small gaol was erected in the centre of the bailey, which was also used for executions. The castle eventually became the county gaol for Cornwall, but was heavily criticised for its poor facilities and treatment of inmates. By 1842, the remaining prisoners had been moved to Bodmin Gaol and the site was closed, the castle being landscaped to form a park by the Duke of Northumberland. During the Second World War, the site was used to host United States Army soldiers and, later, by the Air Ministry for offices. The ministry left the castle in 1956 and the site was reopened to visitors.

In the 21st century, Launceston is owned by the duchy of Cornwall and operated by English Heritage as a tourist attraction. Much of the castle defences remain, including the motte, keep and high tower which overlook the castle's former deer park to the south. The gatehouses and some of the curtain wall have survived, and archaeologists have uncovered the foundations of various buildings in the bailey, including the great hall.

History

11th–12th centuries

Launceston Castle was built after the Norman conquest of England, probably following the capture of Exeter in 1068.[1] It was built at a strategic location, then called Dunheved, controlling the area between Bodmin Moor and Dartmoor, and the access over the Polson ford into Cornwall.[1] It was probably constructed by Robert, the Count of Mortain, who was granted the earldom of Cornwall by William the Conqueror.[2]

The early castle had earth and timber ramparts surrounding a bailey, with a defensive motte in its north-east corner.[3] The bailey was designed around a grid-plan, aligned along its north-south axis, and had a substantial timber hall in the south-west corner.[4] A large number of people lived and worked in wooden buildings that probably filled the site; the historian Oliver Creighton suggests that it would have resembled a "town within a town".[4]

The castle became the administrative centre for the earldom and was used by Robert's court.[5] There was already an existing market held at nearby St Stephen's church by the local canons, but Robert appropriated it and moved the market to outside his new castle, intending to profit from the trade.[6] A watermill was built to the south-west of the castle.[7]

The first documentary record of the castle dates from 1086 and further evidence is limited until the 13th century.[8] Robert's son, William, rebelled against Henry I of England in 1106, who confiscated the castle.[8] Reginald de Dunstanville held it between 1141 and 1175, and it passed to the then Prince John when he acquired the title of the Count of Mortain in 1189, and then passed back into the hands of the Crown after John's rebellion against his brother, Richard I, in 1191.[9] King John gave the castle to Hubert de Burgh, sheriff of Cornwall. [10]

A circular keep was constructed, probably in the late-12th century, on the castle's motte, along with two stone gatehouses and towers along the walls.[11] The wooden buildings in the bailey were rebuilt in stone and the construction work spread up onto the inside edges of the ramparts.[12] Some of these houses may have belonged to the members of the castle-guard, feudal knights who were granted local estates in return for helping to defend the castle.[13]

13th century

Henry III's younger brother, Richard of Cornwall, was granted the earldom in 1227.[12] Backed by the revenues from the lucrative Cornish tin mining industry, he reconstructed the defences at the castle.[14][lower-alpha 1] Richard only visited Cornwall occasionally during his life, probably using Berkhampsted and Wallingford castles as his primary residences in England, and the work may have been designed to impress the Cornish nobility, with whom Richard had a difficult relationship.[16]

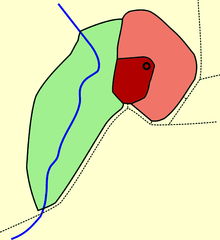

A small deer park was established to the south-west of the castle during this period, incorporating the castle mill within its boundaries, and it was occasionally supplied with deer from Kerrybullock, another park belonging to the earldom.[17][lower-alpha 2] A later survey showed the park being a league–3 miles (4.8 km)–in circumference, and able to hold up to 40 deer.[19]

Richard rebuilt the walls and the gatehouses at Launceston, building a high tower to increase the height of the keep, probably to allow guests to enjoy the view of his deer park.[20] The bailey was cleared of its older buildings and a new great hall was constructed in the south-west corner.[21] The castle's inhabitants ate well, enjoying a wide range of food including prime cuts of venison brought into the castle, probably mostly from the larger deer parks belonging to the earldom across the region.[22]

A town borough was formally created in 1201, and by the 1220s there was a settlement established outside the castle gates; some of those residents who had been moved out of the bailey may have resettled there.[23] Richard built a stone wall around the new town, linking it to the castle defences, intending it both as a defensive measure and to impress visitors.[24]

Richard's son Edmund inherited the earldom in 1272 and moved the administrative hub of the earldom to Lostwithiel, closer to the tin mining industries.[25] Launceston Castle remained significant as a site of local government, but it soon fell into neglect.[26] When Edmund died in 1300, he left no heirs and the property reverted to the Crown.[27]

14th–16th centuries

Edward II gave the earldom, including Launceston Castle, to his royal favourite Piers de Gaveston but, following Gaveston's execution in 1312, the castle passed to Walter de Bottreaux.[28] In 1337, Edward III's son, Edward the Black Prince, was made the first Duke of Cornwall and acquired Launceston Castle.[25] A survey reported a range of problems with the poorly-maintained fortification, noting that the walls–which were supposed to have been repaired by the knights of the castle-guard–were "ruinous", and that various buildings inside the bailey, including two prison buildings, were "decayed" and in need of new roofs.[29] By this time the constable of the castle was living in the north gatehouse.[30] Repairs to Launceston were undertaken in the 1340s and Edward held a council meeting at the castle in 1353, which was increasingly being used mainly for the holding of judicial assizes and as a gaol.[31]

In the 15th century, the castle's bailey was subdivided by a long wall, and the high tower on top of the keep was turned into an additional prison building.[31] Launceston played little part in the dynastic Wars of the Roses that broke out after 1455; the castle was given to the Yorkist favourite Halnatheus Malyverer in 1484, but Henry VII's victory the following year saw him replaced by Sir Richard Edgcumbe.[32] After Edgcumbes death in 1489 his son Piers Edgecumbe took over as constable for life. When the antiquarian John Leland visited in 1539, he noted that the castle was "the strongest, though not the biggest", he had ever seen, but the only buildings he noted were the chapel and the great hall, which was then being used for assize and court sessions.[33]

Launceston Castle played a role in Cornish politics during the middle of the 16th century. In 1548, Sir William Body, a royal commissioner sent by Edward IV to destroy the Catholic shrines at Helston, was killed by two local Cornish men.[34] In retaliation, 28 local men were arrested and executed at the castle.[34] Anger grew, and in 1549 a wider uprising called the Prayer Book Rebellion took place.[35] It was headed by Sir Humphrey Arundell, who marched up through the county and took Launceston Castle that summer, probably without a struggle.[36] The castle was then used to imprison the royalist leader, Sir Richard Grenville, who died during his detention there.[37] John Russell, the Earl of Bedford, subsequently defeated the rebels and retook Launceston, capturing Arundel who was seized in the street fighting.[38]

During the 16th century, the castle began to be used as a rubbish tip by the adjacent town, and under Henry VIII the deer park, which was no longer needed to generate venison for the duchy, fell into disuse.[39] By 1584, the antiquarian John Norden described the castle as "now abandoned", observing that although the hall was very spacious, the chapel was in a state of some decay.[40]

17th–18th centuries

In 1637, Launceston Castle was used to imprison the Puritan writer John Bastwick; contemporary accounts noted that the decaying castle was "so ruinous that every small blast of wind threatened to shatter it down upon his head".[41] Shortly afterwards, the English Civil War broke out between the followers of Charles I and Parliament. The castle was predominantly held by the Royalists, until it was finally taken by the Parliamentarian general, Sir Thomas Fairfax, in February 1646.[42] Before retreating from the town, the Royalist forces reportedly stripped the castle of the lead from its roofs and gave the timbers to the townsfolk to use as fuel.[42] It was left in such a poor condition that Parliament did not bother to slight it, unlike many other captured castles.[42]

A survey in 1650 showed that the town houses and their gardens had encroached on the external defences and that the only inhabitable part of the castle was the north gatehouse; the assizes were moved to a new hall built within the town itself.[43] In the same year, Parliament sold off the properties of the duchy of Cornwall, and Colonel Robert Bennett, a Baptist teacher and supporter of Oliver Cromwell, purchased the castle, its deer park and its gaol.[44] The north gatehouse began to be partially used as a prison, and in 1656 was used to hold various members of the Society of Friends, including George Fox, their founder, who described it as a "nasty stinking place".[45]

When Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660, Bennett was removed from his post as constable.[47] He was initially replaced by Thomas Rosse and then, in 1661, by Philip Piper.[48] A gaol was built in the centre of the bailey in the late-17th century; it was bought by the constable and was adopted as the county gaol.[49] In 1690, the county complained to the King that the constable, Sir Hugh Pyper, had allowed it to fall into disrepair and that the male and female prisoners were sleeping together in the same quarters.[50] Two years later, the Crown granted the post of constable in perpetuity to Hugh and for two generations after him; in exchange, Hugh agreed to invest £120 in repairing the facility.[50] The bailey was also used for carrying out executions.[51][lower-alpha 3]

The Pyper family's control of the constableship concluded in 1754, and George II then appointed a sequence of constables who became responsible for running the castle and county gaol on behalf of the duchy of Cornwall.[53] In 1764, the north gatehouse was partially demolished by Coryndon Carpenter, a former mayor of Launceston and the castle's constable, who used the materials to help built a new mansion alongside the castle, called Eagle House.[54] Parts of the north-west curtain wall were destroyed in the process of his landscaping work.[51] When the artist William Gilpin visited in 1775, he praised the picturesque condition of the ruins.[55]

The prisoner reformer John Howard reported in 1777 that the gaol was very small, forming a main room with three separate cages running along one side; one of these cages was reserved for female prisoners.[56] The upper room was used as a chapel, and food for the inmates was lowered through a hole by the prison gaoler.[56] In 1779, after complaints were made by about the conditions, £500 was granted by Parliament and the gaol was enlarged to comprise a day room and a total of seven cells for male and female prisoners, with accommodation for the prison governor on the first floor.[57][lower-alpha 3] In exchange, the county agreed to take over the maintenance of the gaol.[58] By 1795, Hugh Percy, the 2nd Duke of Northumberland, had become an important local landowner in the region and acquired the rights to the post of constable from the Duke of Cornwall, the then Prince George.[59]

19th–21st centuries

In 1834, Western Road was built along the southern edge of the castle.[60] This required the demolition of part of the castle wall and the fortified bridge, and the weakening of the foundations caused the subsequent collapse of the south-eastern tower later that year.[60] The town of Launceston declined in importance in the 19th century and from 1823 onwards the county gaol, which had a reputation for filthy and unhealthy conditions, began to be run down in favour of the facility at Bodmin Gaol.[61] In 1838 the county government and the assizes were moved to Bodmin, which was more centrally located in Cornwall, resulting in the closure of the castle's gaol and its final demolition in 1842.[62]

By now the castle was in disrepair, and the bailey and the earthworks were covered with a combination of pigsties, cabbage gardens and a skittle alley used by a local pub.[63] Local tradition states that the visiting Queen of Portugal, Maria II of Portugal, complained about the condition of the site to Queen Victoria, which resulted in Hugh Percy, the 3rd Duke of Northumberland and the castle's constable, landscaping the area to create a public park between 1840 and 1842 at a cost of £3,000.[64][lower-alpha 3] The south gatehouse was repaired, and the remains of the north gatehouse turned into stables.[65] Hugh sold off his local interests in 1864 and the Northumberlands' control of the post of constable lapsed with the death of his brother Algernon Percy, the 4th duke, the following year.[66] The post lay vacant until in 1883 the local Member of Parliament, Hardinge Giffard, was appointed as the constable by the then Prince Edward in his capacity as the Duke of Cornwall.[66]

During the later stages of the Second World War, the bailey was levelled and used to hold a set of temporary Nissen huts that formed a hospital for United States Army personnel.[67] In 1945, the site was leased by the Air Ministry for use as offices.[68] The Ministry of Works took over the guardianship of the castle in 1951.[68] The ministry put pressure on the Air Ministry to leave the site, which occurred in 1956; the bailey was then grassed over again.[68] Archaeological excavations were carried out in the bailey between 1961 and 1982, uncovering many of the medieval buildings.[69]

In the 21st century, Launceston Castle is owned by the duchy of Cornwall and operated by English Heritage; as of 2013, annual visitor numbers averaged between 23,000 and 25,000.[70] The remains are protected under UK law as scheduled monuments and a grade I listed building.

Architecture

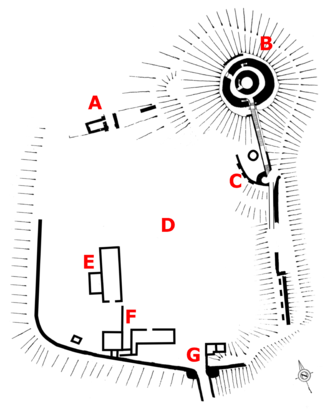

Launceston Castle is built on a ridge that slopes from the east down to its west, where it meets a sharp incline.[71] To the north, the ground drops away to the River Kensey.[72] The castle comprises a curtain wall enclosing a bailey, with the remains of a north and south gatehouse.[73] The inside of the bailey, 110 by 120 metres (360 by 390 ft) across, contains the foundations of various buildings, including the castle's great hall.[74] In the north-east corner is a motte, topped by a keep and the high tower.[75] The majority of the fortifications are built from shale stone, with the detailing carried out in granite and Polyphant stone.[75]

The castle is now entered through the 13th-century southern gatehouse, which faces towards the former deer park.[75] This entrance was once protected by a 14th-century fortified bridge, also called a barbican, but only one set of stone arches remain, showing two surviving arrow slits in arched recesses.[76] The south gatehouse has two drum towers on either side of a gateway, protected by a portcullis, and would have had three floors, linked to a wall walk around the castle.[77] It would originally have been faced with dressed stonework, which has since been removed.[78] The north gatehouse on the opposite site of the bailey originally led into the town of Launceston.[77] The first floor of the building was probably first used as the porter's room, then by the castle's constable, and finally later as a prison.[79]

The rectangular bailey forms a courtyard, the level part of which is called the Castle Green.[80] When first built, the bailey was protected by earth ramparts, until a later stone curtain wall was built around it, protected by at least three mural towers, the foundations of some of which still survive.[81] Much of the wall, including the south-eastern tower–called the Watch or Witch Tower–has been destroyed, although around a stretch 50 metres (160 ft) long survives on the south-west side.[82] The foundations of various, mostly 13th-century buildings excavated during the 20th century can be seen within the bailey, including the great hall, 22 by 7 metres (72 by 23 ft) across; a long narrow hall, possibly used as a courtroom; and a large kitchen.[79] A Victorian cottage is positioned by the south gatehouse, probably on the site of the earl's hall and chamber.[79]

The castle motte was built up in several stages, originally being lower in height than today, before being built up during the medieval period and scarped by cutting away at the surrounding stone.[83] It was then reinforced in 1700 with the addition of clay, before having large quantities of earth dumped on it in the late 18th century, and then being terraced in the mid-19th century.[83] The motte is separated from the bailey by a ditch, now crossed by a modern bridge.[84] In the 13th century this point was protected by a D-shaped tower, which still survives, located to one side of the gateway.[84] The causeway steps up to the top of the mound were originally a roofed, stone corridor.[85] There are the foundations of the castle well on the west side of the causeway.[71]

A circular shell keep, 26 metres (85 ft) across, was constructed on the motte in the 12th century, complete with a gateway; that was later replaced, and the current entrance dates from the 13th century.[86] Rising up through the keep is the 13th-century high tower, 12 metres (39 ft) in diameter, constructed from dark shale.[86] This replaced any internal rooms that the shell keep might have had, instead creating a small, cramped and unlit chamber at the base of the keep.[87] The upper chamber of the high tower was fitted with a large window and a fireplace, overlooking the deer park, and archaeologist Oliver Creighton suggests the tower was intended to be used a "private grandstand", with the parapet below being used for other forms of "lordly display" over the local community.[88] The tower now leans slightly.[85]

The keep appears to lie on the highest ground in the area, although this is actually located to the south, within in the deer park.[89] Visitors would have been funnelled around the edge of the park and by the town wall towards the south gate of the castle, a route dominated by the views of the keep and tower.[90] The addition of the high tower had made the castle visible to anyone entering from Devon, framing it strikingly against the hills.[89] The keep, park and town walls probably symbolised Richard's authority as earl, and the historian Andrew Saunders has argued that the keep and high tower were also intended to resemble Richard of Cornwall's crown in his role as the King of the Romans.[91]

Notes

- The historian Robert Higham has suggested that potentially this work could have been carried out by Edmund of Cornwall, rather than Richard.[15]

- It is uncertain when Launceston deer park was created; the Forest Law had generally limited their construction in Cornwall before 1204 and the first documentary mention of it comes from 1282.[18]

- Comparing early modern costs and prices with those of the modern period is challenging. £120 in 1692 could be equivalent to between £16,900 and £2.96 million in 2015, depending on the price comparison used. £500 in 1779 could be equivalent to between £60,600 and £5.67 million in 2015. £3,000 in 1842 is equivalent to between £254,700 and £11.5 million in 2015.[52]

References

- Jones 1975, p. 5; Higham & Barker 2004, p. 274; Saunders 2002, p. 11

- Jones 1975, p. 5; Saunders 2002, p. 11

- Jones 1975, p. 5; Saunders 2002, pp. 12–13

- Creighton 2002, p. 160; Saunders 2002, pp. 12–13

- Jones 1975, p. 5; Saunders 2002, p. 12

- Creighton 2002, p. 164; Saunders 2002, p. 18; Liddiard 2005, p. 101

- Herring & Gillard 2005, p. 16

- Saunders 2002, p. 12

- Jones 1975, p. 5; Saunders 2002, p. 12; Moss 1999, p. 122

- "Laughton - Laverstoke Pages 33-37 A Topographical Dictionary of England. Originally published by S Lewis, London, 1848". British History Online.

- Saunders 2002, pp. 12–13

- Saunders 2002, p. 13

- Webster & Cherry 1977, p. 234; Pounds 1994, p. 49

- Saunders 2002, pp. 13–14

- Higham 2010, p. 249

- Higham 2010, pp. 245–248

- Herring 2003, pp. 37, 40; North Cornwall District Council, "Luckett: Conservation Area Character Statement" (PDF), Cornwall.gov.uk, p. 3, retrieved 19 November 2016

- Herring 2003, pp. 35–37, 47

- Daniel Lysons and Samuel Lysons (1814), "General History: Deer-parks", British History Online, retrieved 19 November 2016

- Saunders 2002, pp. 1, 13–14; Creighton 2002, p. 81

- Saunders 2002, p. 14

- Creighton 2002, p. 19; Herring 2003, p. 42; Liddiard 2005, p. 103

- Herring & Gillard 2005, pp. 16–17, 48

- Herring & Gillard 2005, p. 17

- Saunders 2002, p. 16

- Saunders 2002, p. 16; Herring & Gillard 2005, p. 19

- Robbins 1888, p. 52

- Robbins 1888, pp. 52–53

- Jones 1975, p. 8; Saunders 2002, pp. 16–17

- Saunders 2002, pp. 16, 20

- Saunders 2002, p. 17

- Robbins 1888, pp. 69–70

- Saunders 2002, p. 17; Britton & Brayley 1832, p. 9

- Mills 2010, p. 198

- Mills 2010, p. 199; Robbins 1888, pp. 93–94

- Robbins 1888, pp. 93–94

- Robbins 1888, p. 53

- Robbins 1888, pp. 53–54

- Creighton 2002, p. 138; Herring & Gillard 2005, p. 19

- Herring & Gillard 2005, p. 20

- Robbins 1888, pp. 148–150

- Saunders 2002, pp. 17–18; Robbins 1888, pp. 180–182

- Saunders 2002, p. 18; Robert J. King (1968), "Launceston Castle", Launceston Then!, retrieved 24 December 2016

- Robbins 1888, pp. 197, 203

- Saunders 2002, p. 20; Robbins 1888, p. 202; Herring & Gillard 2005, p. 22

- Anne L. Cowe. "Launceston Castle, Cornwall". vads. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- Robbins 1888, p. 205

- Robbins 1888, p. 211

- Saunders 2002, p. 19; "Launceston Castle", Historic England, retrieved 19 November 2016

- Robbins 1888, p. 236

- Saunders 2002, p. 19

- Lawrence H. Officer; Samuel H. Williamson (2014), "Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1270 to Present", MeasuringWorth, retrieved 26 November 2016

- Robbins 1888, p. 264; Mackenzie 1896, p. 6

- Saunders 2002, p. 19; Robbins 1888, p. 286; "Launceston Castle", Historic England, retrieved 19 November 2016

- Herring & Gillard 2005, p. 25

- Howard 1777, p. 382

- Saunders 2002, p. 19; Robbins 1888, p. 275; "Launceston Castle", Historic England, retrieved 19 November 2016

- Robbins 1888, p. 275

- Robbins 1888, pp. 286–287

- "Launceston Castle", Historic England, retrieved 19 November 2016; Robbins 1888, pp. 301–302

- Robbins 1888, pp. 302–303; Saunders 2002, pp. 18, 20

- Saunders 2002, pp. 18, 20

- Robbins 1888, p. 330

- Saunders 2002, p. 20; Robbins 1888, p. 331; Mackenzie 1896, p. 6; Herring & Gillard 2005, p. 27; Robert J. King (1968), "Launceston Castle", Launceston Then!, retrieved 24 December 2016

- Robbins 1888, p. 303; "Launceston Castle", Historic England, retrieved 19 November 2016

- Robbins 1888, pp. 262, 365–367; Mackenzie 1896, p. 6

- Saunders 2002, p. 20; "Launceston Castle", Historic England, retrieved 19 November 2016; Robert J. King (1968), "Launceston Castle", Launceston Then!, retrieved 24 December 2016

- Jones 1975, p. 14; Robert J. King (1968), "Launceston Castle", Launceston Then!, retrieved 24 December 2016

- Herring & Gillard 2005, p. 31

- Launceston Town Council, "Minutes of The Tourism and TIC Management Committee held on Monday 15 October 2012", Launceston Town Council, retrieved 19 November 2016

- Saunders 2002, p. 11

- Saunders 2002, p. 11; "Launceston Castle motte, bailey and shell keep", Historic England, retrieved 26 November 2016

- Saunders 2002, p. 3

- Saunders 2002, p. 8; Creighton 2002, p. 160

- Saunders 2002, p. 5

- Saunders 2002, pp. 5–6; Jones 1975, p. 15

- Saunders 2002, p. 6

- Jones 1975, p. 15

- Saunders 2002, p. 8

- Saunders 2002, pp. 7–8; Jones 1975, p. 17

- Saunders 2002, pp. 7–8

- Saunders 2002, p. 7; Jones 1975, p. 17

- Saunders 2002, p. 9

- Saunders 2002, p. 9; Jones 1975, p. 17

- Saunders 2002, p. 10

- Saunders 2002, p. 10; "Launceston Castle motte, bailey and shell keep", Historic England, retrieved 26 November 2016

- Creighton 2013, p. 170

- Creighton 2013, pp. 170–171

- Liddiard 2005, p. 126

- Herring 2003, pp. 47–48; Creighton 2013, p. 158

- Herring 2003, pp. 47–48; Creighton 2013, p. 158; Liddiard 2005, p. 126; Robert Higham (2016), "Shell-keeps revisited: the bailey on the motte?", Castle Studies Group, p. 53, retrieved 19 November 2016

Bibliography

- Britton, John; Brayley, Edward (1832). Devonshire and Cornwall Illustrated. London, UK: H. Fisher, R. Fisher and P. Jackson. OCLC 11571088.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Creighton, Oliver Hamilton (2002). Castles and Landscapes: Power, Community and Fortification in Medieval England. London, UK: Equinox. ISBN 978-1-904768-67-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Creighton, Oliver Hamilton (2013) [2009]. Designs Upon the Land: Elite Landscapes of the Middle Ages. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-825-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Herring, Peter (2003). "Cornish Medieval Deer Parks". In Wilson-North, Robert (ed.). The Lie of the Land: Aspects of the Archaeology and History of the Designed Landscape in the South West of England. Exeter, UK: The Mint Press. pp. 34–50. ISBN 978-1-903356-22-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Herring, Peter; Gillard, Bridget (2005). Launceston. Truro, UK: Cornwall County Council.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Higham, Robert; Barker, Philip (2004) [1992]. Timber Castles. Exeter, UK: University of Exeter Press. ISBN 978-0-85989-753-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Higham, Robert (2010). "Launceston, Lydford, Richard of Cornwall and the Current Debates". The Castle Studies Group Journal. 23: 242–251.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Howard, John (1777). The State of the Prisons in England and Wales. Warrington, UK: W. Eyres. OCLC 2088532.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jones, T. L. (1975) [1959]. Launceston Castle, Cornwall. London, UK: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. ISBN 0-11-670147-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Liddiard, Robert (2005). Castles in Context: Power, Symbolism and Landscape, 1066 to 1500. Macclesfield, UK: Windgather Press. ISBN 0-9545575-2-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mackenzie, James Dixon (1896). Castles of England: Their Story and Structure. 1. New York, US: Macmillan. OCLC 12964492.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mills, Jon (2010). "Genocide and Ethnogenocide: The Suppression of the Cornish Language". In Partridge, John (ed.). Interfaces in Language. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 189–206. ISBN 978-1-4438-2433-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moss, V. D. (1999). "The Norman Exchequer Rolls of King John". In Church, S. D. (ed.). King John: New Interpretations. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. pp. 101–116. ISBN 978-0-85115-736-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pounds, Norman John Greville (1994). The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: a Social and Political History. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45828-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Robbins, Alfred F. (1888). Launceston, Past and Present: A Historical and Descriptive Sketch. Launceston, UK: Walter Weighell. OCLC 221250093.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Saunders, Andrew D. (2002) [1998]. Launceston Castle, Cornwall (revised ed.). London, UK: English Heritage. ISBN 1-85074-020-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Webster, Lesley E.; Cherry, John (1977). "Medieval Britain in 1976". Medieval Archaeology. 21: 204–262.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Albarella, Umberto; Davis, Simon J. M. (1996), "Mammals and Birds from Launceston Castle, Cornwall: Decline in Status and the Rise of Agriculture" (PDF), Circaea, 12 (1): 1–156, ISSN 0268-425X