Didsbury

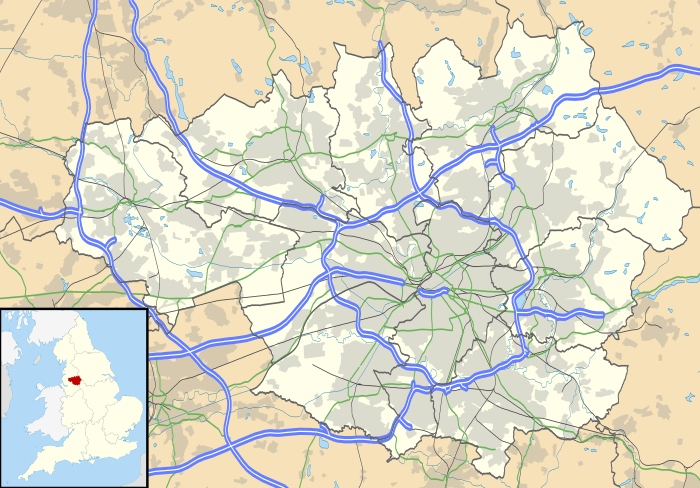

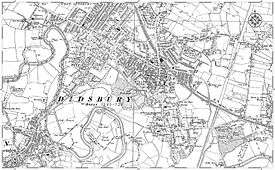

Didsbury is a suburban area of Manchester, England,[1] on the north bank of the River Mersey, 4.5 miles (7.2 km) south of Manchester city centre. The population at the 2011 census was 26,788.[2][3]

| Didsbury | |

|---|---|

The Clock Tower in Didsbury village | |

Didsbury Location within Greater Manchester | |

| Population | 26,788 (Census 2011) |

| OS grid reference | SJ847912 |

| Metropolitan borough | |

| Metropolitan county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | MANCHESTER |

| Postcode district | M20 |

| Dialling code | 0161 |

| Police | Greater Manchester |

| Fire | Greater Manchester |

| Ambulance | North West |

| UK Parliament | |

Historically a part of Lancashire, there are records of Didsbury existing as a small hamlet as early as the 13th century.[4] Its early history was dominated by being part of the Manor of Withington, a feudal estate that covered a large part of what is now the south of Manchester.[5] Didsbury was described during the 18th century as a township separate from outside influence.[6] In 1745 Charles Edward Stuart crossed the Mersey at Didsbury in the Jacobite march south from Manchester to Derby, and again in the subsequent retreat.[7][8]

Didsbury was largely rural until the mid-19th century, when it underwent development and urbanisation during the Industrial Revolution. It became part of Manchester in 1904.[1][4]

The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds was formed in Didsbury in 1889.[9]

History

Toponymy

Didsbury derives its name from the Anglo-Saxon Dyddi's burg, probably referring to a man known as Dyddi whose stronghold or township it was[10] on a low cliff overlooking a place where the River Mersey could be forded. In the 13th century Didsbury was variously referred to as Dydesbyre, Dydesbiri, Didsbury or Dodesbury.[8]

Parish church

A charter granted in about 1260 shows that a corn-grinding mill was operating in Didsbury, along the River Mersey,[8] but the earliest reference to Didsbury is in a document dating from 1235, recording a grant of land for the building of a chapel.[11] The church was named St James Church in 1855. It underwent major refurbishment in 1620 and again in the 19th century, although most of the stonework visible today dates from the 17th century.[12] A parsonage was built next to one of the two public houses that flanked the nearby village green, Ye Olde Cock Inn, so-called because of the cockfighting that used to take place there. The parsonage soon gained a reputation for being haunted; servants refused to sleep on the premises, and it was abandoned in 1850. Local alderman Fletcher Moss bought the house in 1865, and lived in it for more than 40 years. In 1902, he installed a gateway complete with wrought iron gates which he purchased from the soon to be demolished Spread Eagle Hotel in central Manchester which he once owned, at the entrance to the parsonage's garden, which, because of the building's reputation, became known locally as "the gates to Hell". The parsonage became a museum, now closed, but the gardens are still open to the public.[13] The area around St James' Church has the highest concentration of listed buildings in Manchester, outside the city centre.[14]

River Mersey

Didsbury was one of the few places between Stretford and Stockport where the River Mersey could be forded, which made it significant for troop movements during the English Civil War, in which Manchester was on the Parliamentarian side. The Royalist commander, Prince Rupert, stationed himself at Didsbury Ees, to the south of Barlow Moor. It is also likely that Bonnie Prince Charlie crossed the Mersey at Didsbury in 1745, in the Jacobite march south from Manchester to Derby, and again in his subsequent retreat.[7]

Immigration from Europe

Jewish immigrants started to arrive in Manchester from the late 18th century, initially settling mainly in the suburbs to the north of the city. From the 1890s onwards, many of them moved to what were seen as the more "sophisticated" suburbs in the south, such as Withington and Didsbury.[15] The influx of Jewish immigrants led to West Didsbury being nicknamed "Yidsbury" and Palatine Road, a main road through West Didsbury, "Palestine Road".[16]

A growing population of German merchants and industrialists in the mid-19th century earned Manchester the nickname of "the German city". In the Didsbury area, the Souchays were a well-known merchant family of Huguenot descent with connections to Germany. John D. Souchay built Eltville House, a large residence on the corner of Fog Lane and Wilmslow Road (a site bounded today by Clayton Avenue and Clothorn Avenue). The house, named after Eltville in Germany, had a pair of gate lodges at its Wilmslow Road entrance and the Ball Brook ran through its large garden.[17] Other members of the family, Charles (or Carl) and Adelaide (or Adelheid) Souchay, lived nearby at Withington House on Wilmslow Road (the present site of the telephone exchange at Old Broadway). The Souchays were related to Cécile Mendelssohn Bartholdy, wife of the German composer Felix Mendelssohn. In the 1840s, Mendelssohn made several visits to Britain and stayed with the Souchays; he wrote a number of letter to friends with "Eltville House, Withington" as the return address.[18][19] The Souchays were members of St Paul's Church, Withington; Mendelssohn gave a recital on the newly installed pipe organ there in 1847, and the first wedding to take place there was that of John Souchay's eldest daughter in 1850. The Souchays are buried in St Paul's churchyard.[20][21][22]

Eltville House was purchased by Jame Clayton Chorlton in 1888 and he renamed it Didsbury Priory. The Chorltons often opened their private garden to the public during springtime.[17]

19th and 20th centuries

During the Victorian expansion of Manchester, Didsbury developed as a prosperous settlement; a few mansions from the period still exist on Wilmslow Road between Didsbury village and Parrs Wood to the east and Withington to the north, but they have now been converted to nursing homes and offices. The opening of the Manchester South District Line by the Midland Railway in 1880 contributed greatly to the rapid growth in the population of Didsbury. Easy rail connections to Manchester Central were now provided from Didsbury railway station in Didsbury Village, and from Withington and West Didsbury on Palatine Road. Didsbury station was also served by Express trains from Manchester to London St Pancras. Further expansion of the railways ensued when the LNWR's Styal Line from Manchester London Road to Wilmslow opened in 1909, introducing two new stations to the area, East Didsbury and Parrs Wood and Burnage.[23] In 1910, A stone clock tower and water fountain was erected outside Didsbury Midland Railway station in memory of local doctor and campaigner for the poor, Dr. J. Milson Rhodes.[24]

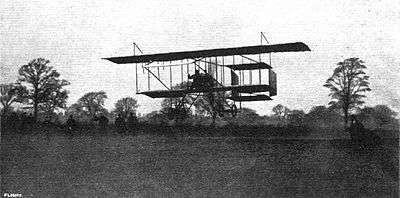

On 28 April 1910, French pilot Louis Paulhan landed his Farman biplane in Barcicroft Fields, Pytha Fold Farm, on the borders of Withington, Burnage and Didsbury, at the end of the first flight from London to Manchester in under 24 hours, with one short overnight stop at Lichfield. Arriving at 5:30 am, Paulhan beat the British contender, Claude Grahame-White, winning a £10,000 prize offered by the Daily Mail.[25] This was the first powered flight into Manchester from any point outside the city. Two special trains were chartered to the newly built but unopened Burnage railway station to take spectators to the landing, many of whom had stood throughout the night. Paulhan's progress was followed throughout by a special train carrying his wife, Henri Farman and his mechanics. Afterwards, his train took the party to a civic reception given by the Lord Mayor of Manchester in the town hall. A house in Paulhan Road, constructed in the 1930s near the site of his landing, is marked by a blue plaque to commemorate his achievement.[26]

In 1921, a war memorial was erected outside Didsbury Library, on the opposite side of the road to the Midland Railway station. Dedicated to the memory of the 174 local servicemen who fell in World War I, it was unveiled by Edward Stanley, 17th Earl of Derby. After World War II, a further 67 names were added.[27][28]

Further transport enhancements came in the form of two new arterial roads which were constructed at the peripheral edges of Didsbury 1928-1930: Kingsway (named after King George V) through East Didsbury; and Princess Road through West Didsbury. Both were laid out as dual carriageways for motor vehicles with a segregated tram track along the central reservation. Manchester Corporation Tramways operated a tram line from Parrs Wood via Burnage into Manchester City Centre until 1949, when the service was closed.[29][30][31]

In the postwar years, passenger train services on the South District Line (now part of British Rail) were gradually reduced, and in 1967 the line was closed during the Beeching Axe. For some years the old station building was in use as Station Hardware and DIY store, before it was demolished in 1982.[6][32][33]

Governance

Civic history

In the early 13th century, Didsbury lay within the manor of Withington, a feudal estate that also included the townships of Withington, Chorlton-cum-Hardy, Moss Side, Rusholme, Burnage, Denton and Haughton, ruled by the Hathersage, Longford and Tatton families,[35] and within the historic county boundaries of Lancashire.[1] Didsbury remained within the manor of Withington for several centuries.

By 1764, Didsbury was described as a township in its own right.[6] It became a civil parish in 1866, and in 1876 was incorporated into the Withington Urban Sanitary District, superseded in 1894 by the creation of Withington Urban District.[36] Withington Urban District was a subdivision of the administrative county of Lancashire, created as part of the provisions of the Local Government Act 1894. In 1904, Withington Urban District was amalgamated into the city and county borough of Manchester, and so Didsbury was absorbed into Manchester, although it remained a civil parish until 1910. Following the Local Government Act 1972, Manchester became a metropolitan borough of the metropolitan county of Greater Manchester.

Political representation

Didsbury is in the parliamentary constituency of Manchester Withington, and is represented by Jeff Smith MP, a member of the Labour Party.[37]

Until 2004, most of the area formed the Didsbury ward of Manchester City Council with a section of West Didsbury contained within the Barlow Moor ward. However, boundary changes in 2004 resulted in Didsbury being split mainly between the two new wards of Didsbury East and Didsbury West while a small section of West Didsbury was incorporated into the new ward of Chorlton Park.[38] Didsbury East is represented by Labour councillors James Wilson, Andrew Simcock and Kelly Simcock.[39] Didsbury West is represented by Labour councillor Greg Stanton, and Liberal Democrat Councillors John Leech and Richard Kilpatrick.[40] All wards within Manchester elect in thirds on a four yearly cycle.

Geography

Didsbury, at 53°24′59″N 2°13′51″W (53.4166, −2.2311), is south of the midpoint of the Greater Manchester Urban Area, 4.5 miles (7.2 km) south of Manchester city centre. To the north, Didsbury is bordered by Withington, Chorlton-cum-Hardy and Burnage, to the west by Northenden, to the east and south-east by Heaton Mersey and Cheadle, and by Gatley to the south.

The River Mersey forms Didsbury's southern and southwestern boundaries and certain stretches of the river also demarcate the boundaries of the City of Manchester. The area is generally considered to be roughly enclosed by Princess Parkway to the west, Kingsway to the east and the Ball Brook, just north of Lapwing Lane/Fog Lane to the north. This northern boundary is marked by a boundary stone in the front garden wall of a house on the west side of Wilmslow Road. A "country trail" passes from West Didsbury to East, named the Trans Pennine Trail (National Cycle Route 62). It was sited along a disused railway track, as part of a nationwide initiative to promote cycling.[41]

Didsbury's built environment has developed around the areas of East Didsbury, West Didsbury, and Didsbury Village, which separates the two. The Albert Park conservation area, covering much of West Didsbury, places planning restrictions on development, alterations to buildings, and pruning of trees. The areas adjacent to the Mersey lie within the river's flood plain, and so have historically been prone to flooding after heavy rainfall.[42] The last major flooding was in the late 1960s. In the 1970s extensive flood mitigation work carried out along the Mersey Valley through Manchester has helped to speed up the passage of floodwater. Fletcher Moss Botanical Garden also acts as an emergency flood basin, storing floodwater until it can be safely released back into the river.[43] Parts of the local flood plain, much of Fletcher Moss Botanical Garden, the whole of nearby Didsbury Park and many of the listed buildings in the area are grouped into the St. James' Conservation area.,[44] which is centred on Wilmslow Road, just south of Didsbury Village.

Demography

| Didsbury Compared[45][46] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK Census 2001 | Didsbury | Manchester | England | |

| Total population | 14,292 | 392,819 | 49,138,831 | |

| Born outside Europe | 8% | 10% | 6% | |

| White | 88% | 81% | 91% | |

| Asian | 8% | 9% | 5% | |

| Black | 1% | 5% | 2% | |

| Over 75 years old | 10% | 6% | 8% | |

The United Kingdom Census 2001 recorded Didsbury as having a population of 14,292, of whom 87% were born in the United Kingdom.[47] A large majority of residents, 88%, identified themselves as white, 8% as Asian, 2% as mixed ethnicity, 1% black and 1% Chinese or other ethnic group.[45] The under-16s accounted for 17% of the population, and the over-65s for 15%. The population density in 2001 was 5,276/square mile (2,037/km²).[48]

Economy

As of the UK's 2001 census, Didsbury had an estimated workforce of 10,755 or 75% of the population. Economic status in Didsbury was: 48% in full-time employment, 11% retired, 10% self-employed, 8% in part-time employment, 4% full-time student (without job), 4% housewife/husband or carer, 4% permanently sick or disabled, 4% unemployed, and 2% economically inactive for unstated reasons.[45] Didsbury's 48% rate of full-time employment compares with 33% in Manchester and 41% across the whole of England.[45] The area's 4% unemployment rate is in contrast to Manchester's rate of 9%, and broadly in line with the 5% rate of unemployment for England.[45]

In 2001, the main industries of employment in Didsbury were 20% property and business services, 15% education, 15% health and social work, 10% retail and wholesale, 9% manufacturing, 6% transport and communications, 5% financial services, 4% hotels and restaurants, 4% construction, 4% public administration and defence, and 8% other.[45] These figures were similar to those from surrounding areas, but Didsbury did have a relatively larger education sector than other nearby wards, perhaps explained by the high density of schools in the area. A significant number of people (12%) commute to areas outside Didsbury; at the 2001 census there were 6,555 jobs in Didsbury, compared with the 7,417 employed residents.[49]

Siemens occupies the Sir William Siemens House in West Didsbury and in 2009 employed 800 people. The head office of BA CityFlyer is in Didsbury.[50] British Airways has an office with 300 employees in Pioneer House on the 292,000 square feet (27,100 m2), Dutch owned Towers Business Park. In 2005, other tenants of the business park included Cisco, IWG], Logica, Trinity Integrated Systems, and Thorn Lighting.[51][52]

Didsbury is considered to form a "stockbroker belt",[53] as it is Manchester's most affluent suburb.[54]

Culture

The original site of Didsbury Village is in the conservation area now known as Didsbury St James,[55] about half a mile (1 km) to the south of what is today's village centre. The old village green is now the beer garden of The Didsbury public house.

The traditional independent retailers are gradually being replaced by multi-national firms, raising fears that Didsbury may lose its individual identity and become a "clone town".[56] However, independent traders continue to thrive, especially in West Didsbury, which celebrates its independent spirit each year with the two-day Westfest festival. The 200-year-old Peacock's Funeral Parlour, one of the few pre-Victorian buildings in the village and regarded by some as the centrepiece of the village,[57] was demolished in the summer of 2005 to make way for a new branch of Boots the Chemists. The owner, United Co-op, blamed changing demographics for the closure of the funeral parlour; with more and more homes being occupied by young professional people, the death rate was falling in the area.[58]

Green areas

The Fletcher Moss Botanical Garden is a 21-acre (85,000 m2) recreational park south of the village centre. It is named after local Alderman Fletcher Moss, who donated the park to the city of Manchester in 1919.[59] In 2008, it won the Green Flag Award, the national standard for parks and green spaces in England,[60] an award it has held since 2000.[61]

Didsbury Park was also a winner of the Green Flag Award in 2008.[62] It is a community park in Didsbury village centre that comprises a bowls area, crèche, football pitch and play area. Once a year, at the Didsbury Festival, pupils from local schools dress up to a theme and meet in the playground of St. Catherine's Primary School, in East Didsbury, from where they parade to Didsbury Park.

Marie Louise Gardens is a relatively small park to the west of the centre of Didsbury. The park was originally owned by the Silkenstadt family as part of the grounds of their house. The land was bequeathed to the people of Manchester by Mrs Silkenstadt in 1904 in memory of her daughter, Marie Louise.[63] The park was at the centre of controversy in 2007 after Manchester City Council proposed to sell a portion of it to a private property developer.[64]

Media

Between 1956 and 1969, the old Capitol Theatre at the junction of Parrs Wood Road and School Lane served as the northern studios of ITV station ABC Weekend Television. Early episodes of The Avengers and programmes such as Opportunity Knocks were made in the studios. ABC ceased to use the site in 1968 when it lost its ITV franchise, on its merger with fellow ITV company Rediffusion. The site was then used briefly by Yorkshire Television until its own facilities in Leeds were ready.[65] In 1971, the studios were acquired by Manchester Polytechnic, who used it for cinema, television studies and theatre.[66] The building was demolished in the late 1990s to make way for a residential development,[65] but the name lives on in the form of a new theatre space in the heart of the M.M.U. campus in the All Saints area along Oxford Road, just to the south of Manchester city centre.[67]

Until 2009 Didsbury was the base for one of the Manchester Evening News subsidiaries, the South Manchester Reporter.[68]

Transport

.jpg)

.jpg)

Didsbury is close to junction 5 of Manchester's ring road, the M60 motorway. Manchester Airport, the busiest airport in the UK outside London,[69] is about 4 miles (6.5 km) to the south.

Bus

Didsbury is served by bus routes on the Wilmslow Road bus corridor, said to be the busiest bus corridor in Europe.[70] There are frequent bus services into Manchester city centre, The Trafford Centre, Northenden, and other destinations.

Rail

The nearest commuter railway stations to Didsbury are East Didsbury and Burnage on the Styal Line, which runs between Manchester Piccadilly and Manchester Airport. The stations were opened in 1909 by the London and North Western Railway.[23] East Didsbury is additionally served by regional trains to destinations such as Liverpool Lime Street and Crewe, Chester and Llandudno.

Until 1967, the suburb was also served by Didsbury station on the South District Line from Manchester Central. The line was closed during the Beeching Axe and the station has been demolished.[32][33]

Metrolink

The area is served by the Manchester Metrolink light rail/tram with three tram stops at Didsbury Village, East Didsbury and West Didsbury.

The tram route uses a reopened section of the former Midland Railway line. Proposals were first announced in 1984 to reopen the disused line as part of the Project Light Rail scheme, and the former Didsbury Station was to re-open under the name of Didsbury Central or Didsbury Village.[71][72] The first phase of the Manchester Metrolink light rail/tram system opened in 1992, but due to funding problems, the old trackbed through Didsbury remained derelict for over 20 years[73][74] until it was reopened in 2013. Rather than reopening the old Midland Railway station on Wilmslow Road, it was decided instead to locate the new Didsbury Village tram stop further down the line at School Lane.[75]

Education

Didsbury has a non-selective education system, assessed by the SATs exam. There are seven primary schools and two state comprehensive secondary schools. The Barlow RC High School is one of those chosen by Manchester Council to benefit from funding made available in wave 4 of the government's Building Schools for the Future programme, a national scheme for the refurbishment and remodelling of every secondary school in England.[76] It is planned to replace all the current buildings, which date back to 1951. Parrs Wood and The Barlow were two of only six schools in Manchester to achieve the Manchester Inclusion Standard in 2007, awarded by Manchester Council to those schools doing innovative work to ensure that all their pupils are able to participate fully in the school's activities.[77]

There is one centre of further and higher education in Didsbury: The Manchester College, (formerly City College Manchester) Fielden Campus, which was opened in 1972 by Margaret Thatcher,[78] offers a variety of courses including communication and technology. Manchester Metropolitan University's Didsbury Campus, the former Didsbury School of Education, was home to the faculties of health, social care, and education, along with the Broomhurst Hall of Residence.[79] The University closed the campus and sold the land in 2014.

Primary schools

- Beaver Road Primary School

- Broad Oak Primary School

- Cavendish Community Primary School

- Didsbury CE Primary School

- St Catherine's RC Primary School

- West Didsbury CE Primary School

Secondary schools

Parrs Wood, with about 2,000 pupils on its register, is much larger than the average, and is regularly over-subscribed in Year 7.[80] In its 2007 inspection report by the Office for Standards in Education, Children's Services and Skills (Ofsted) the school was criticised for "failing to give its pupils an acceptable standard of education", and for providing "unsatisfactory" value for money.[81] However, in 2012 it came out of special measures and Ofsted deemed it a "satisfactory" school with aspects of "good teaching" and "good management".

The Barlow RC High School is an average size secondary school, with about 1,000 pupils. It too is regularly over-subscribed. It was described in its October 2003 Ofsted report as "a successful and effective school that is providing a good education for its pupils".[82]

Special and alternative schools

- The Birches School

- Lancasterian School

Religion

| Religion | Percentage of population[45] |

|---|---|

| Christian | 62% |

| No religion | 20% |

| Not stated | 7% |

| Muslim | 6% |

| Jewish | 2% |

| Hindu | 2% |

It is uncertain when the first chapel was built in Didsbury, but it is thought to have been before the middle of the 13th century. When the plague reached the village in 1352 the chapel yard was consecrated to provide a cemetery for the victims, it being "inconvenient to carry the dead all the way to Manchester".[83]

The BBC Radio 4 Daily Service programme of Christian worship – the world's oldest continuous radio programme – is often broadcast from Emmanuel Church, on Barlow Moor Road.[84][85] Two of Didsbury's religious buildings are Grade II listed: Didsbury Methodist Church of St Paul (now an office building),[86] and the Nazarene Theological College[87] which hosts the Didsbury Lectures. Didsbury was once the location of a Methodist training college, the Wesleyan Theological Institution; the Grade II*-listed building became Didsbury School of Education, part of Manchester Metropolitan University.[86][88] and has now been converted to private housing.

Didsbury is in the Church of England Diocese of Manchester,[89] and the Roman Catholic Diocese of Salford.[90] It is not as religiously diverse as some other areas of Manchester, but it has the second largest Jewish population in the borough and two synagogues: the Shaare Hayim Synagogue and the Sha'are Sedek Synagogue.[91]

Didsbury has a medium-sized Muslim population in comparison with areas such as Rusholme, Longsight and Levenshulme; a converted church in West Didsbury houses the Didsbury Mosque and Islamic Centre.[92]

Sports

Didsbury Sports Centre, on Wilmslow Road, is a part of the Manchester Metropolitan University campus. It provides a fitness suite and classes and facilities for badminton and tennis.

Didsbury has two rugby union clubs, Toc H R.F.C. and Old Bedians. Toc H, founded in 1924, plays at Simons Fields, on Ford Lane.[93] Its first team plays in the North Lancashire and Cumbria league. The club runs four senior teams and a youth section, and has run a 10-a-side competition every May since 1951, as a charity fund raiser for local hospices. Old Bedians is based in East Didsbury, and was founded in 1954. It regularly fields three senior teams as well as a junior section. Desmond Pastore, believed to be the oldest rugby player in the world, was a founder member of the club, and later became its president.[94] Formerly a player for Sale and Cheshire, Desmond played his last game for Manchester club Egor on his 91st birthday.[95] Bedians AFC (an amateur football club founded in 1928) share the Underbank Farm ground with Old Bedians RUFC.

Didsbury Cricket Club fields three Saturday teams and four Sunday teams.[96] The 1st XI plays in the Cheshire County ECB Premier League.[97] As well as the seven senior teams, the club also has a junior section catering for players between 7 and 18 years of age, and has two women's senior teams with multiple women regularly playing in the men's senior teams. It is also home to Manchester Waconians Lacrosse Club and Didsbury Grey's Women's Hockey Team, which do not actually play at the site but at grounds in Belle Vue, that were designed for the XVII Commonwealth Games.[98] Northern Tennis Club, in West Didsbury, is one of Manchester's few racquet clubs; it annually plays host to an Association of Tennis Professionals tournament in July.

Public services

Withington Community Hospital, opened in 2005, occupies part of the site of the former (and much larger) Withington Hospital, developed on the site of a workhouse some of whose buildings are still evident.

Didsbury is covered by the South Manchester Division of Greater Manchester Police.

The Towers, formerly the Shirley Institute, was once the home of engineer Daniel Adamson – the driving force behind the Manchester Ship Canal project – and the venue where the decision to build the canal was taken.[99] The house was designed by Salford architect Thomas Worthington, for the editor and proprietor of the Manchester Guardian, John Edward Taylor.

Notable people

Daniel Adamson, promoter of the Manchester Ship Canal, lived at the Towers (blue plaque – once the Shirley Institute) on Wilmslow Road from 1874 until his death in 1890. His Grade II listed home, designed by Thomas Worthington for John Edward Taylor, the editor and proprietor of the Manchester Guardian, was the venue for the 1882 meeting at which it was decided to construct the ship canal project.[100]

Kathleen Ollerenshaw DBE, mathematician, local politician, co-founder of the Royal Northern College of Music

Emily Williamson, a pioneer of wildlife protection, was a resident of Didsbury from 1882 to 1912. She founded the Plumage League in 1889 and went on to co-found the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) in 1904. In 1989 a plaque was placed on her former home, the Croft, to honour her work on the centenary of her organisation.

Sidney Bernstein and Denis Forman who created Granada Television Manchester also lived in Didsbury during their work requirements at the Granada Studios in Manchester.[101]

Kirsty Howard was the final runner to carry the Queen's Baton at the opening of the 2002 Commonwealth Games, when she was chaperoned by England football captain David Beckham. Born with a rare condition in which her heart is back-to-front, she has been a resident in Didsbury's Francis House Hospice, for which she has raised over £5 million.[102]

Plant ecologist Verona Conway was born in Didsbury in 1910.[103]

Lord Marcus Joseph Sieff, the chairman of Marks & Spencer from 1972 to 1982, was born in Didsbury in 1913.

Francis French, author and noted space historian, grew up in Didsbury, and attended the same school as noted poet and novelist Sophie Hannah.

Carol Ann Duffy, the first female Poet Laureate, lives in West Didsbury as of 2009.

Nigel Henbest, astronomer, author and television producer, was born in West Didsbury in 1951.

Martin Lewis, journalist, was born in Withington and spent his earliest years growing up in Didsbury.

Howard Spring - novelist and journalist for The Manchester Guardian lived in Didsbury 1915-1930 whilst working for the Guardian. Several novels including "Shabby Tiger" were based in Manchester.

See also

References

Citations

- "Greater Manchester Gazetteer". Greater Manchester County Record Office. Places names - D to F. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 2 October 2007.

- "City of Manchester/Didsbury West ward population 2011". Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- "City of Manchester/Didsbury East ward population 2011". Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- "Didsbury St James Conservation Area". manchester.gov.uk. Manchester City Council. History. Retrieved 22 July 2008.

- Sussex & Helm (1988), p. 45

- France, E.; Woodall, T. F. (1976). A New History of Didsbury. E. J. Morten. p. 203. ISBN 0-85972-035-7.

- "Didsbury Village: Didsbury its Lives and Times". Didsbury Civic Society. Archived from the original on 15 May 2008. Retrieved 20 September 2007.

- "History of the Village". British History. Retrieved 20 September 2007.

- "Milestones". Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. Retrieved 29 September 2007.

- "Didsbury: Districts & Suburbs of Manchester". Manchester UK. Papillon Graphics. Archived from the original on 14 September 2007. Retrieved 14 September 2007.

- "Didsbury St James Conservation Area". manchester.gov.uk. Manchester City Council. History. Retrieved 20 September 2007.

- Sussex, Gay; Halm, Peter (1988). Looking back at Withington & Didsbury. Altrincham: Willow Publishing. p. 40. ISBN 0-946361-25-8.

- Cooper (2003), pp. 36–39

- "Didsbury St James Conservation Area". manchester.gov.uk. Manchester City Council. Didsbury St James and its buildings today. Retrieved 20 September 2007.

- "The Moves to the Suburbs". Moving Here, Bill Williams. Retrieved 8 October 2007.

- Zenner (2000), p. 72

- Sussex & Helm 1988, p. 29.

- Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, Felix (2008). Sämtliche Briefe: Februar 1847 bis November 1847 ; Gesamtregister der Bände 1 bis 12 (in German). Bärenreiter. p. 125. ISBN 9783761823125. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

- "Gertrude Clarke Whittall Foundation Collection - Mendelssohn Collection" (PDF). Music Division of the Library of Congress. p. 33. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

- Purver, Ian; Boyle, Roy (5 October 2011). "Church History". St Pauls Withington. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- "Bid to put historic organ on the Mend". Manchester Evening News. 26 March 2009. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

- Mercer-Taylor, Peter. The Life of Mendelssohn. Cambridge University Press. pp. 198-203. ISBN 978-0-521-63972-9.

- Haywood 2009, p. 237.

- Historic England. "Rhodes Memorial Clock (1270515)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- Vivian (2004), pp. 132–133

- Scholefield (2004), p. 211

- Sussex & Helm (1988), p. 30

- Historic England. "Didsbury War Memorial (1270517)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- Crosby, Alan, ed. (1998). Leading the way : a history of Lancashire's roads. Preston: Lancashire County Books. p. 212. ISBN 9781871236330.

- Stratton, Michael; Trinder, Barrie (2014). Twentieth Century Industrial Archaeology. Taylor & Francis. p. 126. ISBN 9781136748011. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- Rowley, Trevor (2006). The English landscape in the twentieth century. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 20. ISBN 1-85285-388-3. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- Suggitt 2004.

- "Didsbury Station". www.disused-stations.org.uk. Disused Stations. Archived from the original on 20 May 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "The Didsbury "Our History"". The Didsbury.

- Sussex & Helm (1988). Looking Back at Withington and Didsbury. Willow. p. 45. ISBN 0-946361-25-8.

- Great Britain Historical GIS Project (2004). "Didsbury Ch/CP through time. Census tables with data for the Parish-level Unit". A vision of Britain through time. University of Portsmouth. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 20 September 2007.

- "Jeff Smith MP". parliament.uk. UK Parliament. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- Elleray, Kirsty (19 December 2003). "Boundary name row rumbles on". South Manchester Reporter. Trinity Mirror. Retrieved 10 May 2008.

- "Didsbury East Councillors". manchester.gov.uk. Manchester City Council. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- "Councillors by Ward: Didsbury West". manchester.gov.uk. Manchester City Council. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- "Cycling in Manchester". manchester.gov.uk. Manchester City Council. Signed Cycle Routes in Manchester. Archived from the original on 15 December 2008. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- "Flooding". SaleCommunityWeb. Retrieved 16 September 2007.

- "Exploring Greater Manchester" (PDF). Manchester Geographical Society. 1998. Retrieved 6 May 2007.

- "St. James' Conservation Area". Manchester City Council. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- United Kingdom Census 2001 (2001). "Area: Didsbury (Ward)". neighbourhood.statistics.gov.uk. Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- United Kingdom Census 2001 (2001). "Greater Manchester (Health Authority)". neighbourhood.statistics.gov.uk. Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- "2001 UK Census (Ethnicity)". Retrieved 6 October 2007.

- "Didsbury Ward" (PDF). Manchester City Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 January 2008. Retrieved 5 October 2007.

- "Distance Travelled to Work – Workplace Population (UV80)". Area: Didsbury (Ward). Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 8 October 2007.

- "BA City Flyer". BA City. Archived from the original on 22 November 2009. Retrieved 12 March 2010. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - "BA". BA web. Retrieved 12 March 2010. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Thame, David (6 September 2005). "Didsbury Towers is going Dutch". Manchester Evening News. M.E.N. Media. Retrieved 12 March 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "£1m house puts Didsbury into the stockbroker belt". South Manchester Reporter. M.E.N. Media. 1 March 2002. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- Burdett, Jill (25 May 2005). "Didsbury's first £1m apartments". Manchester Evening News. M.E.N. Media. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- "Didsbury St James Conservation Area". manchester.gov.uk. Manchester City Council. Townscape. Retrieved 20 September 2007.

- Towle, Nick (8 December 2005). "Fears over 'clone town' Didsbury". South Manchester Reporter. M.E.N. Media. Retrieved 18 September 2007.

- "Dying to Save Peacocks". BBC. 20 February 2006. Archived from the original on 23 August 2007. Retrieved 16 September 2007.

- Towle, Nick (5 May 2005). "Death of a funeral parlour". South Manchester Reporter. M.E.N. Media. Retrieved 16 September 2007.

- "History of Fletcher Moss Gardens". Manchester City Council. Archived from the original on 4 January 2008. Retrieved 21 October 2007.

- "Fletcher Moss Gardens". Green Flag Award. Archived from the original on 7 February 2008. Retrieved 29 September 2007.

- "About Fletcher Moss Gardens". Manchester City Council. Archived from the original on 4 January 2008. Retrieved 29 September 2007.

- "Didsbury Park". Green Flag Award. Archived from the original on 7 February 2008. Retrieved 29 September 2007.

- "Manchester Parks and Gardens". John Moss, Papillon Graphics. Archived from the original on 22 September 2007. Retrieved 21 September 2007.

- Wright, Susannah (7 June 2007). "Hands off our park, say 5,000 residents". South Manchester Report. Retrieved 21 September 2007.

- Graham, Russ J. "From the North". Transdiffusion Broadcasting System. Archived from the original on 14 October 2007. Retrieved 3 October 2007. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Rudyard & Wyke 1994, p. 29

- "About us". Manchester School of Theatre. Archived from the original on 26 October 2010. Retrieved 20 September 2010. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - "SMR Profile". South Manchester Reporter. 3 April 2007. Archived from the original on 19 September 2007. Retrieved 4 September 2007. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Wilson, James (26 April 2007). "A busy hub of connectivity". Financial Times – FT report – doing business in Manchester and the NorthWest. The Financial Times Limited.

- O'Rourke, Aidan (26 October 2006). "Didsbury as the "busiest bus corridor"". EyeOnManchester. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 3 September 2007.

- Greater Manchester Passenger Transport Executive (1984), Light Rapid Transit in Greater Manchester, GMPTE – publicity brochure

- Ogden, Eric; Senior, John (1991). Metrolink: Official Handbook. Glossop, Derbyshire: Transport Publishing Company. pp. 26–27. ISBN 0-86317-164-8.

- Williams, Tony (30 May 2007). "Manchester to Chorlton and East Didsbury". Light Transit Association. Archived from the original on 21 December 2008. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- Cronshaw, Andy (22 July 2004). "Fight for Metrolink will go on". South Manchester Reporter. M.E.N. Media. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- Kirby, Dean (23 May 2013). "First passengers travel on tram extension to East Didsbury". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "New boost for education in Manchester as council gets funding to rebuild more secondary Schools". manchester.gov.uk. Manchester City Council. Retrieved 16 September 2007.

- "More Schools Achieve Manchester Inclusion Standard". manchester.gov.uk. Manchester City Council. Retrieved 7 August 2007.

- "Fielden Campus". City College Manchester. Archived from the original on 1 June 2008. Retrieved 8 October 2007.

- "ManMet Campus". MMU. Archived from the original on 22 September 2007. Retrieved 18 September 2007.

- "Parrs Wood Campus and Facilities". Parrs Wood High School. Archived from the original on 5 April 2010. Retrieved 22 February 2010.

- "Parrs Wood High School". Ofsted. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- Henderson, A (October 2003). Inspection Report: The Barlow RC High School (Report). Office for Standards in Education, Children's Services and Skills. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- "Didsbury". A History of the County of Lancaster: Volume 4. British history Online. Retrieved 18 October 2007.

- "Religion & Ethics". BBC. Retrieved 16 October 2007.

- "Regional Churches". manchesteronline.co.uk. Retrieved 16 October 2007.

- "A-Z of Listed Buildings in Manchester". manchester.gov.uk. Manchester City Council. Listed buildings in Manchester by street (W). Retrieved 17 October 2007.

- "A-Z of Listed Buildings in Manchester". manchester.gov.uk. Manchester City Council. Listed buildings in Manchester by street (D). Retrieved 17 October 2007.

- Historic England. "Administration Building at Didsbury Campus, Manchester Metropolitan University (original portion only) (1254970)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- "The Church of England Diocese of Manchester". Archived from the original on 27 December 2007. Retrieved 7 May 2007.

- "Parishes of the Diocese". Catholic Diocese of Salford. Archived from the original on 2 May 2007. Retrieved 7 May 2007.

- "Places of Worship". didsburylife.com. Archived from the original on 3 December 2010. Retrieved 17 October 2007.

- "SJ8391: Church near to West Didsbury, Manchester, Great Britain". Geograph British Isles. geograph. Retrieved 17 October 2007.

- "Team Profile". DidsburyRFC. Archived from the original on 15 May 2008. Retrieved 18 September 2007.

- "History". Old Bedians. Archived from the original on 23 May 2008. Retrieved 17 September 2007.

- "Rugby star, 91, honoured by Queen". BBC News. 17 June 2006. Retrieved 17 September 2007.

- "Didsbury Cricket Club". www.didsburycc.com. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- "Cheshire County Cricket League". cheshirecountycl.play-cricket.com. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- "Didsbury Sports (Page 2 – Bottom left)" (PDF). DidsburyCCsports. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 18 September 2007.

- "The Towers History". Retrieved 2 October 2007.

- "The Towers". manchester2002-uk. Archived from the original on 7 August 2007. Retrieved 18 September 2007.

- Forman, Denis (1997). Persona Granada. Andre Deutsch. ISBN 0-233-98987-0.

- "Kirsty Howard hits £5m target". Manchester Evening News. M.E.N. Media. 30 October 2006. Retrieved 3 October 2007.

- Pigott, Donald (1988). "Obituary: Verona Margaret Conway: (1910-1986)". Journal of Ecology. 76 (1): 288–291. ISSN 0022-0477. JSTOR 2260470.

Bibliography

- Cooper, Glynis (2003), Hidden Manchester, Breedon Books Publishing, ISBN 1-85983-401-9

- Haywood, Russ (2009). Railways, Urban Development and Town Planning in Britain: 1948-2008. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 9780754673927. Retrieved 19 June 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sussex, Gay; Helm, Peter (1988), Looking Back at Withington and Didsbury, Willow, ISBN 0-946361-25-8

- Rudyard, Nigel; Wyke, Terry (1994), Manchester Theatres, Bibliography of North West England, ISBN 0-947969-18-7

- Scholefield, R. A. (2004), Manchester's Early Airfields, an extended article in Moving Manchester, Lancashire & Cheshire Antiquarian Society, ISSN 0950-4699

- Suggitt, Gordon (2004). Lost Railways of Merseyside and Greater Manchester. Countryside Books. ISBN 978-1-85306-869-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vivian, E. Charles (2004), A History of Aeronautics, Kessinger Publishing, ISBN 1-4191-0156-0

- Zenner, Walter P. (2000), A Global Community: The Jews from Aleppo, Syria, Wayne State University Press, ISBN 0-8143-2791-5

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |