Opiliones

The Opiliones (/oʊˌpɪliˈoʊniːz/ or /ɒˌpɪliˈoʊnɛz/; formerly Phalangida) are an order of arachnids colloquially known as harvestmen, harvesters, or daddy longlegs. As of April 2017, over 6,650 species of harvestmen have been discovered worldwide,[1] although the total number of extant species may exceed 10,000.[2] The order Opiliones includes five suborders: Cyphophthalmi, Eupnoi, Dyspnoi, Laniatores, and Tetrophthalmi, which were named in 2014.[3]

| Opiliones | |

|---|---|

| |

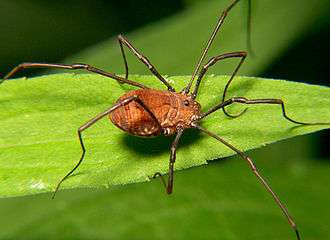

| Hadrobunus grandis showing its body structure and long legs: one pair of eyes and broadly joined body tagma differentiate it from similar-looking arachnids | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Chelicerata |

| Class: | Arachnida |

| Order: | Opiliones Sundevall, 1833 |

| Suborders | |

| Diversity | |

| 5 suborders, > 6,650 species | |

Representatives of each extant suborder can be found on all continents except Antarctica.

Well-preserved fossils have been found in the 400-million-year-old Rhynie cherts of Scotland, and 305-million-year-old rocks in France, which look surprisingly modern, indicating that their basic body shape developed very early on,[4] and, at least in some taxa, has changed little since that time.

Their phylogenetic position within the Arachnida is disputed; their closest relatives may be the mites (Acari) or the Novogenuata (the Scorpiones, Pseudoscorpiones, and Solifugae).[5] Although superficially similar to and often misidentified as spiders (order Araneae), the Opiliones are a distinct order that is not closely related to spiders. They can be easily distinguished from long-legged spiders by their fused body regions and single pair of eyes in the middle of the cephalothorax. Spiders have a distinct abdomen that is separated from the cephalothorax by a constriction, and they have three to four pairs of eyes, usually around the margins of the cephalothorax.

English speakers may colloquially refer to species of Opiliones as "daddy longlegs" or "granddaddy longlegs", but this name is also used for two other distantly related groups of arthropods, the crane flies of the family Tipulidae, and the cellar spiders of the family Pholcidae, most likely because of their similar appearance. Harvestmen are also referred to as "shepherd spiders" in reference to how their unusually long legs reminded observers of the ways that some European shepherds used stilts to better observe their wandering flocks from a distance.[6]

Description

.jpg)

The Opiliones are known for having exceptionally long legs relative to their body size; however, some species are short-legged. As in all Arachnida, the body in the Opiliones has two tagmata, the anterior cephalothorax or prosoma, and the posterior 10-segmented abdomen or opisthosoma. The most easily discernible difference between harvestmen and spiders is that in harvestmen, the connection between the cephalothorax and abdomen is broad, so that the body appears to be a single oval structure. Other differences include the fact that Opiliones have no venom glands in their chelicerae, so pose no danger to humans.

They also have no silk glands and therefore do not build webs. In some highly derived species, the first five abdominal segments are fused into a dorsal shield called the scutum, which in most such species is fused with the carapace. Some such Opiliones only have this shield in the males. In some species, the two posterior abdominal segments are reduced. Some of them are divided medially on the surface to form two plates beside each other. The second pair of legs is longer than the others and function as antennae or feelers. In short-legged species, this may not be obvious.

The feeding apparatus (stomotheca) differs from most arachnids in that Opiliones can swallow chunks of solid food, not only liquids. The stomotheca is formed by extensions of the coxae of the pedipalps and the first pair of legs.

Most Opiliones, except for Cyphophthalmi, have a single pair of eyes in the middle of the head, oriented sideways. Eyes in Cyphophthalmi, when present, are located laterally, near the ozopores. A 305-million-year-old fossilized harvestman with two pairs of eyes was reported in 2014. This find indicates that the eyes in Cyphophthalmi are not homologous to the eyes of other harvestmen.[7][8] However, some species are eyeless, such as the Brazilian Caecobunus termitarum (Grassatores) from termite nests, Giupponia chagasi (Gonyleptidae) from caves, most species of Cyphophthalmi, and all species of the Guasiniidae.[9]

Harvestmen have a pair of prosomatic defensive scent glands (ozopores) that secrete a peculiar-smelling fluid when disturbed. In some species, the fluid contains noxious quinones. They do not have book lungs, and breathe through tracheae. A pair of spiracles is located between the base of the fourth pair of legs and the abdomen, with one opening on each side. In more active species, spiracles are also found upon the tibia of the legs. They have a gonopore on the ventral cephalothorax, and the copulation is direct as male Opiliones have a penis, unlike other arachnids. All species lay eggs.

The legs continue to twitch after they are detached because 'pacemakers' are located in the ends of the first long segment (femur) of their legs. These pacemakers send signals via the nerves to the muscles to extend the leg and then the leg relaxes between signals. While some harvestman's legs twitch for a minute, others have been recorded to twitch up to an hour. The twitching has been hypothesized to function as an evolutionary advantage by keeping the attention of a predator while the harvestman escapes.[2]

Typical body length does not exceed 7 mm (0.28 in), and some species are smaller than 1 mm, although the largest known species, Trogulus torosus (Trogulidae), grows as long as 22 mm (0.87 in).[2] The leg span of many species is much greater than the body length and sometimes exceeds 160 mm (6.3 in) and to 340 mm (13 in) in Southeast Asia.[10] Most species live for a year.

Behavior

Many species are omnivorous, eating primarily small insects and all kinds of plant material and fungi, and a few have also been found to prey on amphibians[11]. Some are scavengers, feeding upon dead organisms, bird dung, and other fecal material. Such a broad range is unusual in other arachnids, which are typically pure predators. Most hunting harvestmen ambush their prey, although active hunting is also found. Because their eyes cannot form images, they use their second pair of legs as antennae to explore their environment. Unlike most other arachnids, harvestmen do not have a sucking stomach or a filtering mechanism. Rather, they ingest small particles of their food, thus making them vulnerable to internal parasites such as gregarines.[2]

Although parthenogenetic species do occur, most harvestmen reproduce sexually. Mating involves direct copulation, rather than the deposition of a spermatophore. The males of some species offer a secretion (nuptial gift) from their chelicerae to the female before copulation. Sometimes, the male guards the female after copulation, and in many species, the males defend territories. In some species, males also exhibit post-copulatory behavior in which the male specifically seeks out and shakes the female's sensory leg. This is believed to entice the female into mating a second time.[12]

The females lay eggs from an ovipositor shortly after mating to several months later. Some species build nests for this purpose. A unique feature of harvestmen is that some species practice parental care, in which the male is solely responsible for guarding the eggs resulting from multiple partners, often against egg-eating females, and cleaning the eggs regularly.[13] Depending on circumstances such as temperature, the eggs may hatch at any time after the first 20 days, up to about half a year after being laid. Harvestmen variously pass through four to eight nymphal instars to reach maturity, with most known species having six instars.[2]

Most species are nocturnal and colored in hues of brown, although a number of diurnal species are known, some of which have vivid patterns in yellow, green, and black with varied reddish and blackish mottling and reticulation.

Many species of harvestmen easily tolerate members of their own species, with aggregations of many individuals often found at protected sites near water. These aggregations may number 200 individuals in the Laniatores, and more than 70,000 in certain Eupnoi. Gregarious behavior is likely a strategy against climatic odds, but also against predators, combining the effect of scent secretions, and reducing the probability of any particular individual being eaten.[2]

Harvestmen clean their legs after eating by drawing each leg in turn through their jaws.

Antipredator defenses

Predators of harvestmen include a variety of animals, including some mammals[14][15], amphibians, and other arachnids like spiders[16][17] and scorpions.[18] Opiliones display a variety of primary and secondary defenses against predation,[19] ranging from morphological traits such as body armor to behavioral responses to chemical secretions.[20][21] Some of these defenses have been attributed and restricted to specific groups of harvestmen.[22]

Primary defenses

Primary defenses help the harvestmen avoid encountering a potential predator, and include crypsis, aposematism, and mimicry.

Crypsis

Particular patterns or color markings on harvestmen's bodies can reduce detection by disrupting the animals' outlines or providing camouflage. Markings on legs can cause an interruption of the leg outline and loss of leg proportion recognition.[23] Darker colorations and patterns function as camouflage when they remain motionless.[24] Within the genus Leiobunum are multiple species with cryptic coloration that changes over ontogeny to match the microhabitat used at each life stage.[22][25] Many species have also been able to camouflage their bodies by covering with secretions and debris from the leaf litter found in their environments.[22][26] Some hard-bodied harvestmen have epizoic cyanobacteria and liverworts growing on their bodies that suggest potential benefits for camouflage against large backgrounds to avoid detection by diurnal predators.[27][28]

Aposematism and mimicry

Some harvestmen have elaborate and brightly colored patterns or appendages which contrast with the body coloration, potentially serving as an aposematic warning to potential predators.[22][29][30] This mechanism is thought to be commonly used during daylight, when they could be easily seen by any predators.

Other harvestmen may exhibit mimicry to resemble other species’ appearances. Some Gonyleptidae individuals that produce translucid secretions have orange markings on their carapaces. This may have an aposematic role by mimicking the coloration of glandular emissions of two other quinone-producing species.[29] Mimicry (Müllerian mimicry) occurring between Brazilian harvestmen that resemble others could be explained by convergent evolution.[22]

Secondary defenses

Secondary defenses allow for harvestmen to escape and survive from a predator after direct or indirect contact, including thanatosis, freezing, bobbing, autotomy, fleeing, stridulation, retaliation, and chemical secretions.

Thanatosis

Some animals respond to attacks by simulating an apparent death to avoid either detection or further attacks.[31] Arachnids such as spiders practice this mechanism when threatened or even to avoid being eaten by female spiders after mating.[32][33] Thanatosis is used as a second line of defense when detected by a potential predator and is commonly observed within the Dyspnoi and Laniatores suborders,[30] with individuals becoming rigid with legs either retracted or stretched.[34][35][36][37]

Freezing

Freezing – or the complete halt of movement – has been documented in the family Sclerosomatidae.[38] While this can mean an increased likelihood of immediate survival, it also leads to reduced food and water intake.[39]

Bobbing

To deflect attacks and enhance escape, long-legged species – commonly known as daddy long-legs – from the Eupnoi suborder, use two mechanisms. One is bobbing, for which these particular individuals bounce their bodies. It potentially serves to confuse and deflect any identification of the exact location of their bodies.[22][39][40][41] This can be a deceiving mechanism to avoid predation when they are in a large aggregation of individuals, which are all trembling at the same time.[22][42] Cellar spiders (Pholcidae) that are commonly mistaken for daddy long-legs (Opiliones) also exhibit this behavior when their webs are disturbed or even during courtship.[43]

Autotomy

Autotomy is the voluntary amputation of an appendage, and is employed to escape when restrained by a predator.[44][45][46][47] Eupnoi individuals, more specifically sclerosomatid harvestmen, commonly use this strategy in response to being captured.[42][48][49] This strategy can be costly because harvestmen do not regenerate their legs,[22] and leg loss reduces locomotion, speed, climbing ability, sensory perception, food detection, and territoriality.[42][49][48][50]

Autotomized legs provide a further defense from predators because they can twitch for 60 seconds to an hour after detachment.[46] This can also potentially serve as deflection from an attack and deceive a predator from attacking the animal. It has been shown to be successful against ants and spiders.[35]

Fleeing

Individuals that are able to detect potential threats can flee rapidly from attack. This is seen with multiple long-legged species in the Leiobunum clade that either drop and run, or drop and remain motionless.[51] This is also seen when disturbing an aggregation of multiple individuals, where they all scatter.[22][42]

Stridulation

Multiple species within the Laniatores and Dyspnoi possess stridulating organs, which are used as intraspecific communication and have also been shown to be used as a second line of defense when restrained by a predator.[30]

Retaliation

Armored harvestmen in Laniatores can often use their modified morphology as weapons.[16][52][53] Many have spines on their pedipalps, back legs, or bodies.[22][54] By pinching with their chelicerae and pedipalps, they can cause harm to a potential predator.[16] Also this has been proven to increase survival against recluse spiders by causing injury, allowing the harvestman to escape from predation.[53]

Chemical

Harvestmen are well known for being chemically protected. They exude strongly odored secretions from their scent glands, called ozopores,[22][24][29][36][55] that act as a shield against predators; this is the most effective defense they use which creates a strong and unpleasant taste.[52] These secretions have successfully protected the harvestmen against wandering spiders (Ctenidae),[16][17] wolf spiders (Lycosidae) and Formica exsectoides ants.[21] However, these chemical irritants are not able to prevent four species of harvestmen being preyed upon by the black scorpion Bothriurus bonariensis (Bothriuridae).[18] These secretions contain multiple volatile compounds that vary among individuals and clades.[56][57][58]

Endangered status

All troglobitic species (of all animal taxa) are considered to be at least threatened in Brazil. Four species of Opiliones are on the Brazilian national list of endangered species, all of them cave-dwelling: Giupponia chagasi, Iandumoema uai, Pachylospeleus strinatii and Spaeleoleptes spaeleus.

Several Opiliones in Argentina appear to be vulnerable, if not endangered. These include Pachyloidellus fulvigranulatus, which is found only on top of Cerro Uritorco, the highest peak in the Sierras Chicas chain (provincia de Cordoba) and Pachyloides borellii is in rainforest patches in northwest Argentina which are in an area being dramatically destroyed by humans. The cave-living Picunchenops spelaeus is apparently endangered through human action. So far, no harvestman has been included in any kind of a Red List in Argentina, so they receive no protection.

Maiorerus randoi has only been found in one cave in the Canary Islands. It is included in the Catálogo Nacional de especies amenazadas (National catalog of threatened species) from the Spanish government.

Texella reddelli and Texella reyesi are listed as endangered species in the United States. Both are from caves in central Texas. Texella cokendolpheri from a cave in central Texas and Calicina minor, Microcina edgewoodensis, Microcina homi, Microcina jungi, Microcina leei, Microcina lumi, and Microcina tiburona from around springs and other restricted habitats of central California are being considered for listing as endangered species, but as yet receive no protection.

Misconception

An urban legend claims that the harvestman is the most venomous animal in the world,[59] but possesses fangs too short or a mouth too round and small to bite a human, rendering it harmless (the same myth applies to Pholcus phalangioides and the cranefly, which are both also called a 'daddy longlegs').[60] This is untrue on several counts. None of the known species of harvestmen has venom glands; their chelicerae are not hollowed fangs but grasping claws that are typically very small and not strong enough to break human skin.

Research

Harvestmen are a scientifically neglected group. Description of new taxa has always been dependent on the activity of a few dedicated taxonomists. Carl Friedrich Roewer described about a third (2,260) of today's known species from the 1910s to the 1950s, and published the landmark systematic work Die Weberknechte der Erde (Harvestmen of the World) in 1923, with descriptions of all species known to that time. Other important taxonomists in this field include: Pierre Latreille (18th century) Carl Ludwig Koch, Maximilian Perty (1830s-1850s) L. Koch, Tord Tamerlan Teodor Thorell (1860s-1870s) Eugène Simon, William Sørensen (1880s-1890s) James C. Cokendolpher, Raymond Forster, Jürgen Gruber, Reginald Frederick Lawrence, Jochen Martens, Cândido Firmino de Mello-Leitão (20th century) Gonzalo Giribet, Adriano Brilhante Kury, Tone Novak (21st century).

Since the 1990s, study of the biology and ecology of harvestmen has intensified, especially in South America.[2]

Phylogeny

Harvestmen are ancient arachnids. Fossils from the Devonian Rhynie chert, 410 million years ago, already show characteristics like tracheae and sexual organs, indicating that the group has lived on land since that time. Despite being similar in appearance to, and often confused with, spiders, they are probably closely related to the scorpions, pseudoscorpions, and solifuges; these four orders form the clade Dromopoda. The Opiliones have remained almost unchanged morphologically over a long period.[2][4] Indeed, one species discovered in China, Mesobunus martensi, fossilized by fine-grained volcanic ash around 165 million years ago, is hardly discernible from modern-day harvestmen and has been placed in the extant family Sclerosomatidae.[61][62]

Etymology

The Swedish naturalist and arachnologist Carl Jakob Sundevall (1801–1875) honored the naturalist Martin Lister (1638–1712) by adopting Lister's term Opiliones for this order, known in Lister's days as "harvest spiders" or "shepherd spiders", from Latin opilio, "shepherd"; Lister characterized three species from England (although not formally describing them, being a pre-Linnean work).[63]

Systematics

The interfamilial relationships within Opiliones are not yet fully resolved, although significant strides have been made in recent years to determine these relationships. The following list is a compilation of interfamilial relationships recovered from several recent phylogenetic studies, although the placement and even monophyly of several taxa are still in question.[64][65][66][67][68]

- Suborder Cyphophthalmi Simon 1879 (about 200 species)

- Infraorder Boreophthalmi Giribet 2012

- Family Sironidae Simon 1879

- Family Stylocellidae Hansen & Sørensen 1904

- Infraorder Scopulophthalmi Giribet 2012

- Family Pettalidae Shear 1980

- Infraorder Sternophthalmi Giribet 2012

- FamilyTroglosironidae Shear 1993

- Superfamily Ogoveoidea Shear 1980

- Family Neogoveidae Shear 1980

- Family Ogoveidae Shear 1980

- Suborder Eupnoi Hansen & Sørensen 1904 (about 1,800 species)

- Superfamily Caddoidea Banks 1892

- Family Caddidae Banks 1892

- Superfamily Phalangioidea Latreille 1802

- Family Neopilionidae Lawrence 1931

- Family Phalangiidae Latreille 1802

- Family Protolophidae Banks 1893

- Family Sclerosomatidae Simon 1879

- Suborder Dyspnoi Hansen & Sørensen 1904 (about 400 species)

- Superfamily Acropsopilionoidea Roewer 1923

- Family Acropsopilionidae Roewer 1923

- Superfamily Ischyropsalidoidea Simon 1879

- Family Ischyropsalididae Simon 1879

- Family Sabaconidae Dresco 1970

- Family Taracidae Schönhofer 2013

- Superfamily Troguloidea Sundevall 1833

- Family Dicranolasmatidae Simon 1879

- Family Nemastomatidae Simon 1872

- Family Nipponopsalididae Martens 1976

- Family Trogulidae Sundevall 1833

- Suborder Laniatores Thorell, 1876 (about 4,200 species)

- Infraorder Insidiatores Loman, 1900

- Superfamily Travunioidea Absolon & Kratochvil 1932

- Family Cladonychiidae Hadži 1935

- Family Cryptomastridae Derkarabetian & Hedin 2018

- Family Paranonychidae Briggs 1971

- Family Travuniidae Absolon & Kratochvil 1932

- Superfamily Triaenonychoidea Sørensen, 1886

- Family Synthetonychiidae Forster 1954

- Family Triaenonychidae Sørensen, 1886

- Infraorder Grassatores Kury, 2002

- Superfamily Assamioidea Sørensen, 1884

- Family Assamiidae Sørensen, 1884

- Family Pyramidopidae Sharma and Giribet, 2011

- Superfamily Epedanoidea Sørensen, 1886

- Family Epedanidae Sørensen, 1886

- Family Petrobunidae Sharma and Giribet, 2011

- Family Podoctidae Roewer, 1912

- Family Tithaeidae Sharma and Giribet, 2011

- Superfamily Gonyleptoidea Sundevall, 1833

- Family Agoristenidae Šilhavý, 1973

- Family Otilioleptidae Acosta, 2019

- Family Cosmetidae Koch, 1839

- Family Cranaidae Roewer, 1913

- Family Cryptogeobiidae Kury, 2014

- Family Gerdesiidae Bragagnolo, 2015

- Family Gonyleptidae Sundevall, 1833

- Family Manaosbiidae Roewer, 1943

- Family Metasarcidae Kury, 1994

- Family Nomoclastidae Roewer, 1943

- Family Stygnidae Simon, 1879

- Family Stygnopsidae Sørensen, 1932

- Superfamily Phalangodoidea Simon, 1879

- Family Phalangodidae Simon, 1879

- Superfamily Samooidea Sørensen, 1886

- Family Biantidae Thorell, 1889

- Family Samoidae Sørensen, 1886

- Family Stygnommatidae Roewer, 1923

- Superfamily Sandokanoidea Özdikmen & Kury, 2007

- Family Sandokanidae Özdikmen & Kury, 2007

- Superfamily Zalmoxoidea Sørensen, 1886

- Family Escadabiidae Kury & Pérez, 2003

- Family Fissiphalliidae Martens, 1988

- Family Guasiniidae Gonzalez-Sponga, 1997

- Family Icaleptidae Kury & Pérez, 2002

- Family Kimulidae Pérez González, Kury & Alonso-Zarazaga, 2007

- Family Zalmoxidae Sørensen, 1886

The family Stygophalangiidae (one species, Stygophalangium karamani) from underground waters in North Macedonia is sometimes misplaced in the Phalangioidea. It is not a harvestman.

Fossil record

Despite their long history, few harvestman fossils are known. This is mainly due to their delicate body structure and terrestrial habitat, making them unlikely to be found in sediments. As a consequence, most known fossils have been preserved within amber.

The oldest known harvestman, from the 410-million-year-old Devonian Rhynie chert, displayed almost all the characteristics of modern species, placing the origin of harvestmen in the Silurian, or even earlier. A recent molecular study of Opiliones, however, dated the origin of the order at about 473 million years ago (Mya), during the Ordovician.[69]

No fossils of the Cyphophthalmi or Laniatores much older than 50 million years are known, despite the former presenting a basal clade, and the latter having probably diverged from the Dyspnoi more than 300 Mya.

Naturally, most finds are from comparatively recent times. More than 20 fossil species are known from the Cenozoic, three from the Mesozoic,[62] and at least seven from the Paleozoic.[70]

Paleozoic

The 410-million-year-old Eophalangium sheari is known from two specimens, one a female, the other a male. The female bears an ovipositor and is about 10 mm (0.39 in) long, whilst the male had a discernable penis. Whether both specimens belong to the same species is not definitely known. They have long legs, tracheae, and no median eyes. Together with the 305-million-year-old Hastocularis argus, it forms the suborder Tetrophthalmi.[3][71]

Brigantibunum listoni from East Kirkton near Edinburgh in Scotland is almost 340 million years old. Its placement is rather uncertain, apart from it being a harvestman.

From about 300 Mya, several finds are from the Coal Measures of North America and Europe.[3][4] While the two described Nemastomoides species are currently grouped as Dyspnoi, they look more like Eupnoi.

Kustarachne tenuipes was shown in 2004 to be a harvestman, after residing for almost one hundred years in its own arachnid order, the "Kustarachnida".

Some fossils from the Permian are possibly harvestmen, but these are not well preserved.

Described species

- Eophalangium sheari Dunlop, 2004 (Tetrophthalmi) — Early Devonian (Rhynie, Scotland)

- Brigantibunum listoni Dunlop, 2005 (Eupnoi?) — Early Carboniferous (East Kirkton, Scotland)

- Echinopustulus samuelnelsoni Dunlop, 2004 (Dyspnoi?) — Upper Carboniferous (Western Missouri, U.S.)

- Eotrogulus fayoli Thevenin, 1901 (Dyspnoi: † Eotrogulidae) — Upper Carboniferous (Commentry, France)

- Hastocularis argus Garwood, 2014 (Tetrophthalmi) — Upper Carboniferous (Montceau-les-Mines, France)

- Kustarachne tenuipes Scudder, 1890 (Eupnoi?) — Upper Carboniferous (Mazon Creek, U.S.)

- Nemastomoides elaveris Thevenin, 1901 (Dyspnoi: † Nemastomoididae) — Upper Carboniferous (Commentary, France)

- Nemastomoides longipes Petrunkevitch, 1913 (Dyspnoi: † Nemastomoididae) — Upper Carboniferous (Mazon Creek, U.S.)

Mesozoic

Currently, no fossil harvestmen are known from the Triassic. So far, they are also absent from the Lower Cretaceous Crato Formation of Brazil, a Lagerstätte that has yielded many other terrestrial arachnids. An unnamed long-legged harvestman was reported from the Early Cretaceous of Koonwarra, Victoria, Australia, which may be a Eupnoi.

A fossil of Halitherses grimaldii, a long-legged Dyspnoi with large eyes, was found in Burmese amber dating from approximately 100 Mya. It has been suggested that this may be related to the Ortholasmatinae (Nemastomatidae).[72]

Cenozoic

Unless otherwise noted, all species are from the Eocene.

- Trogulus longipes Haupt, 1956 (Dyspnoi: Trogulidae) — Geiseltal, Germany

- Philacarus hispaniolensis (Laniatores: Samoidae?) — Dominican amber

- Kimula species (Laniatores: Kimulidae) — Dominican amber

- Hummelinckiolus silhavyi Cokendolpher & Poinar, 1998 (Laniatores: Samoidae) — Dominican amber

- Caddo dentipalpis (Eupnoi: Caddidae) — Baltic amber

- Dicranopalpus ramiger (Koch & Berendt, 1854) (Eupnoi: Phalangiidae) — Baltic amber

- Opilio ovalis (Eupnoi: Phalangiidae?) — Baltic amber

- Cheiromachus coriaceus Menge, 1854 (Eupnoi: Phalangiidae?) — Baltic amber

- Leiobunum longipes (Eupnoi: Sclerosomatidae) — Baltic amber

- Histricostoma tuberculatum (Dyspnoi: Nemastomatidae) — Baltic amber

- Mitostoma denticulatum (Dyspnoi: Nemastomatidae) — Baltic amber

- Nemastoma incertum (Dyspnoi: Nemastomatidae) — Baltic amber

- Sabacon claviger (Dyspnoi: Sabaconidae) — Baltic amber

- Petrunkevitchiana oculata (Petrunkevitch, 1922) (Eupnoi: Phalangioidea) — Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument, USA (Oligocene)

- Proholoscotolemon nemastomoides (Laniatores: Cladonychiidae) — Baltic amber

- Siro platypedibus (Cyphophthalmi: Sironidae) — Bitterfeld amber

- Amauropilio atavus (Cockerell, 1907) (Eupnoi: Sclerosomatidae) — Florissant, USA (Oligocene)

- Amauropilio lacoei (A. lawei?) (Petrunkevitch, 1922) — Florissant, USA (Oligocene)

- Pellobunus proavus Cokendolpher, 1987 (Laniatores: Samoidae) — Dominican amber

- Phalangium species (Eupnoi: Phalangiidae) — near Rome, Italy (Quaternary)

See also

References

- Kury, Adriano B. "Classification of Opiliones". www.museunacional.ufrj.br. Retrieved 2017-11-29.

- Glauco Machado, Ricardo Pinto-da-Rocha & Gonzalo Giribet (2007). "What are harvestmen?". In Ricardo Pinto-da-Rocha, Glauco Machado & Gonzalo Giribet (ed.). Harvestmen: the Biology of Opiliones. Harvard University Press. pp. 1–13. ISBN 978-0-674-02343-7.

- Garwood, Russell J.; Sharma, Prashant P.; Dunlop, Jason A.; Giribet, Gonzalo (2014). "A Paleozoic Stem Group to Mite Harvestmen Revealed through Integration of Phylogenetics and Development". Current Biology. 24 (9): 1017–1023. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.039. PMID 24726154. Retrieved April 17, 2014.

- Garwood, Russell J.; Dunlop, Jason A.; Giribet, Gonzalo; Sutton, Mark D. (2011). "Anatomically modern Carboniferous harvestmen demonstrate early cladogenesis and stasis in Opiliones". Nature Communications. 2: 444. doi:10.1038/ncomms1458. PMID 21863011.

- Shultz, J. W. (1990). "Evolutionary morphology and phylogeny of Arachnida". Cladistics. 6: 1–38. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.1990.tb00523.x.

- Joyce Tavolacci, ed. (2003), Insects and spiders of the world, Volume 5: Harvester ant to leaf-cutting ant, Marshall Cavendish, p. 263, ISBN 978-0-7614-7334-3

- 4-Eyed Daddy Longlegs Helps Explain Arachnid Evolution

- Garwood, RJ; Sharma, PP; Dunlop, JA; Giribet, G (2014). "A Paleozoic Stem Group to Mite Harvestmen Revealed through Integration of Phylogenetics and Development". Curr Biol. 24 (9): 1017–23. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.039. PMID 24726154. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- Pinto-da-Rocha, Ricardo; Kury, Adriano B. (2003). "Third species of Guasiniidae (Opiliones, Laniatores) with comments on familial relationships" (PDF). Journal of Arachnology. 31 (3): 394–399. doi:10.1636/H02-59.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-11-19. Retrieved 2015-05-29.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Valdez, Jose W. "Arthropods as vertebrate predators: A review of global patterns". Global Ecology and Biogeography. n/a (n/a). doi:10.1111/geb.13157. ISSN 1466-8238.

- Fowler-Finn, K.D.; Triana, E.; Miller, O.G. (2014). "Mating in the harvestman Lieobunum vittatum (Arachnida: Opiliones): from premating struggles to solicitous tactile engagement". Behaviour. 151 (12–13): 1663–1686. doi:10.1163/1568539x-00003209. S2CID 49329266.

- Machado, G.; Raimundo, R. L. G. (2001). "Parental investment and the evolution of subsocial behaviour in harvestmen (Arachnida: Opiliones)". Ethology Ecology & Evolution. 13 (2): 133–150. doi:10.1080/08927014.2001.9522780. S2CID 18019589.

- Cáceres, N.C. (2002). "Food Habits and Seed Dispersal by the White-Eared Opossum, Didelphis albiventris, in Southern Brazil". Stud. Neotropical Fauna Environ. 37 (2): 97–104. doi:10.1076/snfe.37.2.97.8582.

- Cáceres, N.C.; Monteiro-Filho, E.L.A (2001). "Food Habits, Home Range and Activity of Didelphis aurita (Mammalia, Marsupialia) in a Forest Fragment of Southern Brazil". Stud. Neotropical Fauna Environ. 36 (2): 85–92. doi:10.1076/snfe.36.2.85.2138.

- da Silva Souza, E.; Willemart, R.H. (2011). "Harvest-ironman: heavy armature, and not its defensive secretions, protects a harvestman against a spider". Anim. Behav. 81: 127–133. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2010.09.023.

- Willemart, R.H.; Pellegatti-Franco, F. (2006). "The spider Enoploctenus cyclothorax (Araneae, Ctenidae) avoids preying on the harvestman Mischonyx cuspidatus (Opiliones, Gonyleptidae)". J. Arachnol. 34 (3): 649–652. doi:10.1636/S05-70.1.

- Albín, A., Toscano-Gadea, C.A., 2015. Predation among armored arachnids: Bothriurus bonariensis (Scorpions, Bothriuridae) versus four species of harvestmen (Harvestmen, Gonyleptidae). Behav. Processes 121, 1–7.

- Edmunds, M., 1974. Defence in animals. A survey of antipredator defenses.

- Lind, Johan; Cresswell, Will (2005). "Determining the fitness consequences of antipredation behavior". Behavioral Ecology. 16 (5): 945–956. doi:10.1093/beheco/ari075.

- Machado, Glauco; Carrera, Patricia C.; Pomini, Armando M.; Marsaioli, Anita J. (2005). "Chemical Defense in Harvestmen (Arachnida, Opiliones): Do Benzoquinone Secretions Deter Invertebrate and Vertebrate Predators?". Journal of Chemical Ecology. 31 (11): 2519–2539. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.384.1362. doi:10.1007/s10886-005-7611-0. PMID 16273426.

- Gnaspini, P., Hara, M.R., 2007. Defense mechanisms. Harvestmen: The Biology of Opiliones. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, pp.374-399.

- Cokendolpher pers. comm.

- Gnaspini, P., Cavalheiro, A.J., 1998. Chemical and Behavioral Defenses of a Neotropical Cavernicolous Harvestman: Goniosoma spelaeum (Opiliones, Laniatores, Gonyleptidae). J. Arachnol. 26, 81–90.

- Edgar, A.L., 1971. Studies on the biology and ecology of Michigan Phalangida (Opiliones).

- Firmo, C., Pinto-da-Rocha, R., 2002. A new species of pseudotrogulus roewer and assignment of the genus to the hernandariinae (opiliones, gonyleptidae). J. Arachnol. 30, 173–176.

- Machado, G., Vital, D.M., 2001. On the Occurrence of Epizoic Cyanobacteria and Liverworts on a Neotropical Harvestman (Arachnida: Opiliones) | BIOTROPICA

- Proud, D.N., Wade, R.R., Rock, P., Townsend, V.R., Chavez, D.J., 2012. Epizoic cyanobacteria associated with a Neotropical harvestman (Opiliones: Sclerosomatidae) from Costa Rica. J. Arachnol. 40, 259–261.

- González, A., Rossini, C., Eisner, T., 2004. Mimicry: imitative depiction of discharged defensive secretion on carapace of an opilionid. CHEMOECOLOGY 14, 5–7.

- Pomini, A.M., Machado, G., Pinto-da-Rocha, R., Macías-Ordóñez, R., Marsaioli, A.J., 2010. Lines of defense in the harvestman Hoplobunus mexicanus (Arachnida: Opiliones): Aposematism, stridulation, thanatosis, and irritant chemicals. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 38, 300–308.

- Humphreys, R.K., Ruxton, G.D., 2018. A review of thanatosis (death feigning) as an anti-predator behaviour. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 72, 22.

- Hansen, L.S., Gonzales, S.F., Toft, S., Bilde, T., 2008. Thanatosis as an adaptive male mating strategy in the nuptial gift–giving spider Pisaura mirabilis. Behav. Ecol. 19, 546–551.

- Jones, T.C., Akoury, T.S., Hauser, C.K., Moore, D., 2011. Evidence of circadian rhythm in antipredator behaviour in the orb-weaving spider Larinioides cornutus. Anim. Behav. 82, 549–555.

- Cokendolpher, J.C., 1987. Observations on the defensive behaviors of a Neotropical Gonyleptidae (Arachnida, Opiliones). Revue Arachnologique, 7, pp.59-63.

- Eisner, T., Alsop, D., Meinwald, J., 1978. Secretions of Opilionids, Whip Scorpions and Pseudoscorpions, in: Arthropod Venoms, Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology / Handbuch Der Experimentellen Pharmakologie. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp. 87–99.

- Machado, G., Pomini, A.M., 2008. Chemical and behavioral defenses of the neotropical harvestman Camarana flavipalpi (Arachnida: Opiliones). Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 36, 369–376.

- Pereira, W., Elpino-Campos, A., Del-Claro, K., Machado, G., 2004. Behavioral repertory of the neotropical harvestman ilhaia cuspidata (opiliones, gonyleptidae). J. Arachnol. 32, 22–30.

- Misslin, R., 2003. The defense system of fear: behavior and neurocircuitry. Neurophysiol. Clin. Neurophysiol. 33, 55–66.

- Chelini, M.-C., Willemart, R.H., Hebets, E.A., 2009. Costs and benefits of freezing behaviour in the harvestman Eumesosoma roeweri (Arachnida, Opiliones). Behav. Processes 82, 153–159.

- Field, L.H., Glasgow, S., 2001. The Biology of Wetas, King Crickets and Their Allies. CABI

- Holmberg, R.G., Angerilli, N.P.D., LaCasse, L.J., 1984. Overwintering Aggregations of Leiobunum paessleri in Caves and Mines (Arachnida, Opiliones). J. Arachnol. 12, 195–204.

- Escalante, I., Albín, A., Aisenberg, A., 2013. Lacking sensory (rather than locomotive) legs affects locomotion but not food detection in the harvestman Holmbergiana weyenberghi. Can. J. Zool. 91, 726–731.

- Huber, B.A., Eberhard, W.G., 1997. Courtship, copulation, and genital mechanics in Physocyclus globosus (Araneae, Pholcidae). Can. J. Zool. 75, 905–918.

- Domínguez, M., Escalante, I., Carrasco-Rueda, F., Figuerola-Hernández, C.E., Marta Ayup, M., Umaña, M.N., Ramos, D., González-Zamora, A., Brizuela, C., Delgado, W., Pacheco-Esquivel, J., 2016. Losing legs and walking hard: effects of autotomy and different substrates in the locomotion of harvestmen in the genus Prionostemma. J. Arachnol. 44, 76–82.

- Fleming, P.A., Muller, D., Bateman, P.W., 2007. Leave it all behind: a taxonomic perspective of autotomy in invertebrates. Biological Reviews.

- Roth, V.D., Roth, B.M., 1984. review of appendotomy in spiders and other arachnids. Bull.-Br. Arachnol. Soc.

- Mattoni, C.I., García Hernández, S., Botero-Trujillo, R., Ochoa, J.A., Ojanguren-Affilastro, A.A., Outeda-Jorge, S., Pinto-da-Rocha, R. and Yamaguti, H.Y., 2001. Perder la cola o la vida. In Primer caso de autotomía en escorpiones (Scorpiones: Buthidae). III Congreso Latinoamericano de Aracnología, Memorias y Resúmenes (pp. 83-84).

- Houghton, J.E., Townsend, V.R., Proud, D.N., 2011. The Ecological Significance of Leg Autotomy for Climbing Temperate Species of Harvestmen (Arachnida, Opiliones, Sclerosomatidae). Southeast. Nat. 10, 579–590.

- Guffey, C., 1998. Leg Autotomy and Its Potential Fitness Costs for Two Species of Harvestmen (Arachnida, Opiliones). J. Arachnol. 26, 296–302.

- Macias-Ordonez, R., 1998. The mating system of Leiobunum vittatum Say 1821 (Arachnida: Opiliones: Palpatores): Resource defense polygyny in the striped harvestman.

- Machado, G., Raimundo, R.L.G., Oliveira, P.S., 2000. Daily activity schedule, gregariousness, and defensive behaviour in the Neotropical harvestman Goniosoma longipes (Opiliones: Gonyleptidae): Journal of Natural History: Vol 34, No 4.

- Dias, B.C., Willemart, R.H., 2013. The effectiveness of post-contact defenses in a prey with no pre-contact detection. Zoology 116, 168–174.

- Segovia, J.M.G., Del-Claro, K., Willemart, R.H., 2015. Defences of a Neotropical harvestman against different levels of threat by the recluse spider. Behaviour 152, 757–773.

- Eisner, T., Eisner, M., Siegler, M., 2005. Secret Weapons: Defenses of Insects, Spiders, Scorpions, and Other Many-legged Creatures. Harvard University Press.

- Shultz, J.W., Pinto-da-Rocha, R., 2007. Morphology and functional anatomy. Harvest. Biol. Opiliones Harv. Univ. Press Camb. Mass. Lond. Engl. 14–61.

- Gnaspini, P., Rodrigues, G.S., 2011. Comparative study of the morphology of the gland opening area among Grassatores harvestmen (Arachnida, Opiliones, Laniatores)of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research.

- Hara, M.R., Gnaspini, P., 2003. Comparative study of the defensive behavior and morphology of the gland opening area among harvestmen (Arachnida, Opiliones, Gonyleptidae) under a phylogenetic perspective.

- Shear, W.A., Jones, T.H., Guidry, H.M., Derkarabetian, S., Richart, C.H., Minor, M., Lewis, J.J., 2014. Chemical defenses in the opilionid infraorder Insidiatores: divergence in chemical defenses between Triaenonychidae and Travunioidea and within travunioid harvestmen (Opiliones) from eastern and western North America | Journal of Arachnology.

- Berenbaum, May R. (30 September 2009). The Earwig's Tail: a modern bestiary of multi-legged legends. Harvard University Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-674-05356-4.

- The Spider Myths Site: Daddy-Longlegs Archived 2007-07-28 at WebCite

- Perkins, Sid (June 23, 2009). "Long-lasting daddy longlegs". Science News.

- Diying Huang, Paul A. Selden & Jason A. Dunlop (2009). "Harvestmen (Arachnida: Opiliones) from the Middle Jurassic of China" (PDF). Naturwissenschaften. 96 (8): 955–962. doi:10.1007/s00114-009-0556-3. PMID 19495718.

- Martin Lister's English Spiders, 1678. Ed. John Parker and Basil Hartley (1992). Colchester, Essex: Harley Books. pp. 26 & 30. (Translation of the Latin original, Tractatus de Araneis.)

- Giribet, Gonzalo; Sharma, Prashant P.; Benavides, Ligia R.; Boyer, Sarah L.; Clouse, Ronald M.; De Bivort, Benjamin L.; Dimitrov, Dimitar; Kawauchi, Gisele Y.; Murienne, Jerome (2012-01-01). "Evolutionary and biogeographical history of an ancient and global group of arachnids (Arachnida: Opiliones: Cyphophthalmi) with a new taxonomic arrangement". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 105 (1): 92–130. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2011.01774.x. ISSN 1095-8312.

- Kury, Adriano B.; Villarreal M., Osvaldo (2015-05-01). "The prickly blade mapped: establishing homologies and a chaetotaxy for macrosetae of penis ventral plate in Gonyleptoidea (Arachnida, Opiliones, Laniatores)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 174 (1): 1–46. doi:10.1111/zoj.12225. ISSN 1096-3642. S2CID 84029705.

- Fernández R, Sharma PP, Tourinho AL, Giribet G. 2017 The Opiliones tree of life: shedding light on harvestmen relationships through transcriptomics. Proc. R. Soc. B 284: 20162340. https://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2016.2340

- Groh, Selina; Giribet, Gonzalo (2015-06-01). "Polyphyly of Caddoidea, reinstatement of the family Acropsopilionidae in Dyspnoi, and a revised classification system of Palpatores (Arachnida, Opiliones)". Cladistics. 31 (3): 277–290. doi:10.1111/cla.12087. ISSN 1096-0031.

- Kury, Adriano B.; Mendes, Amanda Cruz; Souza, Daniele R. (2014-11-05). "World Checklist of Opiliones species (Arachnida). Part 1: Laniatores – Travunioidea and Triaenonychoidea". Biodiversity Data Journal. 2 (2): e4094. doi:10.3897/BDJ.2.e4094. ISSN 1314-2836. PMC 4238074. PMID 25425936.

- Sharma, Prashant P.; Giribet, Gonzalo (2014). "A revised dated phylogeny of the arachnid order Opiliones". Frontiers in Genetics. 5: 255. doi:10.3389/fgene.2014.00255. ISSN 1664-8021. PMC 4112917. PMID 25120562.

- Dunlop, Jason A. (2007). "Paleontology". In Ricardo Pinto-da-Rocha, Glauco Machado & Gonzalo Giribet (ed.). Harvestmen: the Biology of Opiliones. Harvard University Press. pp. 247–265. ISBN 978-0-674-02343-7.

- Tepper, Fabien (April 11, 2014). "Ancient four-eyed wonder resolves daddy longleg mystery". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- Giribet, Gonzalo; Dunlop, Jason A. (2005). "First identifiable Mesozoic harvestman (Opiliones: Dyspnoi) from Cretaceous Burmese amber". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 272 (1567): 1007–1013. doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3063. PMC 1599874. PMID 16024358.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Opiliones. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Opiliones |

- Joel Hallan's Biology Catalog (2005)

- Harvestman: Order Opiliones Diagnostic photographs and information on North American harvestmen

- Harvestman: Order Opiliones Diagnostic photographs and information on European harvestmen

- University of Aberdeen: The Rhynie Chert Harvestmen (fossils)

- National Museum page Classification of Opiliones A synoptic taxonomic arrangement of the order Opiliones, down to family-group level, including some photos of the families

- Pocock, Reginald Innes (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.).