Alan Rickman

Alan Sidney Patrick Rickman (21 February 1946 – 14 January 2016) was an English actor and director. Known for his languid tone and delivery, Rickman's signature sound was the result of a speech impediment when he could not move his lower jaw properly as a child.[1] He trained at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London and became a member of the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC), performing in modern and classical theatre productions. He played the Vicomte de Valmont in the RSC stage production of Les Liaisons Dangereuses in 1985, and after the production transferred to the West End in 1986 and Broadway in 1987 he was nominated for a Tony Award.

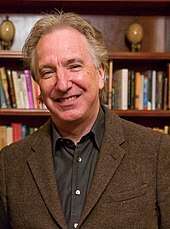

Alan Rickman | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Rickman in 2011 | |

| Born | Alan Sidney Patrick Rickman 21 February 1946 London, England |

| Died | 14 January 2016 (aged 69) London, England |

| Education | Latymer Upper School |

| Alma mater | Chelsea College of Art and Design |

| Occupation | Actor, director |

| Years active | 1974–2016 |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Awards | Full list |

Rickman's first cinematic role was as the German terrorist leader Hans Gruber in Die Hard (1988). He also appeared as the Sheriff of Nottingham in Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991), for which he received the BAFTA Award for Best Actor in a Supporting Role; Elliott Marston in Quigley Down Under (1990); Jamie in Truly, Madly, Deeply (1990); P.L. O'Hara in An Awfully Big Adventure (1995); Colonel Brandon in Sense and Sensibility (1995); Alexander Dane in Galaxy Quest (1999); Severus Snape in the Harry Potter series; Harry in Love Actually (2003); Marvin the Paranoid Android in The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (2005); and Judge Turpin in the film adaptation of Stephen Sondheim's musical of Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street (2007).

Rickman made his television acting debut playing Tybalt in Romeo and Juliet (1978) as part of the BBC's Shakespeare series. His breakthrough role was in the BBC television adaptation of The Barchester Chronicles (1982). He later starred in television films, playing the title character in Rasputin: Dark Servant of Destiny (1996), which won him a Golden Globe Award, an Emmy Award and a Screen Actors Guild Award, and Dr. Alfred Blalock in Something the Lord Made (2004). Rickman died of pancreatic cancer on 14 January 2016 at age 69.[2][3] His final film roles were as Lieutenant General Frank Benson in the thriller Eye in the Sky (2015), and reprising his role as the voice of the caterpillar from Alice in Wonderland (2010) in Alice Through the Looking Glass (2016).

Early life

Alan Sidney Patrick Rickman was born into a working-class family in Acton, west London[4] on 21 February 1946.[5][6] He was the son of a Welsh mother, Margaret Doreen Rose (née Bartlett),[7][8][9] a housewife,[6][10] and Bernard William Rickman,[11][12] a factory worker, house painter and decorator, and former World War II aircraft fitter.[6][10][13] Rickman was of Irish and Welsh descent.[14] His father was Catholic and his mother was a Methodist.[15] Rickman had two brothers, David and Michael, and a sister, Sheila.[6] Rickman was born with a tight jaw, which resulted in the languid tone of his voice.[16] When he was eight years old, his father died of lung cancer, leaving his mother to raise him and his three siblings mostly alone. According to Paton, the family was "rehoused by the council and moved to an Acton estate to the west of Wormwood Scrubs Prison, where his mother struggled to bring up four children on her own by working for the Post Office."[6][17] She married again in 1960, but divorced Rickman's stepfather after three years.[6][15][18]

Before Rickman met Rima Horton at age 19, he stated that his first crush was at 10 years old on a girl named Amanda at his school's sports day.[19] As a child, he excelled at calligraphy and watercolour painting. Rickman attended West Acton First School[20] followed by Derwentwater Primary School in Acton, and then Latymer Upper School in London through the Direct Grant system, where he became involved in drama. After leaving Latymer with science A Levels, he attended Chelsea College of Art and Design from 1965 to 1968[21] and then the Royal College of Art from 1968 to 1970.[22] His training allowed him to work as a graphic designer for the Royal College of Art's in-house magazine, ARK, and the Notting Hill Herald, which he considered a more stable occupation than acting; he later said that drama school "wasn't considered the sensible thing to do at 18".[23][24][25] After graduation, Rickman and several friends opened a graphic design studio called Graphiti, but after three years of successful business, he decided that he was going to pursue acting professionally. He wrote to request an audition with the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA),[26] which he attended from 1972 until 1974. While there, he supported himself by working as a dresser for Nigel Hawthorne and Sir Ralph Richardson.[27]

Career

After graduating from RADA, Rickman worked extensively with British repertory and experimental theatre groups in productions including Chekhov's The Seagull and Snoo Wilson's The Grass Widow at the Royal Court Theatre, and appeared three times at the Edinburgh International Festival. In 1978, he performed with the Court Drama Group, gaining roles in Romeo and Juliet and A View from the Bridge, among other plays. While working with the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC), he was cast in As You Like It. His breakthrough role was in The Barchester Chronicles (1982), the BBC's adaptation of Trollope's first two Barchester novels, as the Reverend Obadiah Slope.[1][28][29]

—Empire on Rickman, ranking his portrayals of the Sheriff of Nottingham (number 14) and Hans Gruber (number 4) on their list of the greatest villains.[30]

Rickman was given the male lead, the Vicomte de Valmont, in the 1985 Royal Shakespeare Company production of Christopher Hampton's adaptation of Les Liaisons Dangereuses, directed by Howard Davies.[31] After the RSC production transferred to the West End in 1986 and Broadway in 1987, Rickman received both a Tony Award nomination and a Drama Desk Award nomination for his performance.[32]

Rickman played a wide range of roles. He played romantic leads including Colonel Brandon in Sense and Sensibility (1995) and Jamie in Truly, Madly, Deeply (1991); numerous villains in Hollywood big-budget films, including German criminal Hans Gruber in Die Hard (1988), Australian Elliot Marston opposite Tom Selleck in Quigley Down Under (1990) and the Sheriff of Nottingham in Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991); and the occasional television role such as Dr. Alfred Blalock in HBO's Something the Lord Made (2004) and the "mad monk" Rasputin in the HBO biopic Rasputin: Dark Servant of Destiny (1996), for which he won a Golden Globe Award and an Emmy Award.[33]

Rickman's role as Hans Gruber in Die Hard earned him a spot on the AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains list as the 46th best villain in film history, though he revealed he almost did not take the role as he did not think Die Hard was the kind of film he wanted to make.[34] His performance as the Sheriff of Nottingham in Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves—which saw him win the BAFTA Award for Best Actor in a Supporting Role—also earned him praise as one of the best actors to portray a villain in films.[35][36]

Rickman took issue with being typecast as a villain, even though he was known for playing "unsympathetic characters".[37] His portrayal of Severus Snape, the potions master in the Harry Potter series (2001–2011), was dark, but the character's motivations were not clear early on.[38] During his career, Rickman played comedic roles, including as Sir Alexander Dane/Dr. Lazarus in the sci-fi parody Galaxy Quest (1999), the angel Metatron, the voice of God, in Dogma (also 1999), Emma Thompson's character's foolish husband Harry in the British Christmas-themed romantic comedy Love Actually (2003), providing the voice of Marvin the Paranoid Android in The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (2005) and playing the egotistical, Nobel Prize-winning father in Nobel Son (2007).

Rickman was nominated for an Emmy for his work as Dr. Alfred Blalock in HBO's Something the Lord Made (2004). He also starred in the independent film Snow Cake (2006) with Sigourney Weaver and Carrie-Anne Moss, and Perfume: The Story of a Murderer (also 2006), directed by Tom Tykwer. He appeared as Judge Turpin in the critically acclaimed Tim Burton film Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street (2007) alongside Harry Potter co-stars Helena Bonham Carter and Timothy Spall. He provided the voice of Absolem the Caterpillar in Burton's film Alice in Wonderland (2010).[39]

Rickman performed onstage in Noël Coward's romantic comedy Private Lives, which transferred to Broadway after its successful run in London at the Albery Theatre and ended in September 2002; he reunited with his Les Liaisons Dangereuses co-star Lindsay Duncan and director Howard Davies in the Tony Award-winning production. Rickman's previous stage performance was in Antony and Cleopatra in 1998 as Mark Antony, with Helen Mirren as Cleopatra, in the Royal National Theatre's production at the Olivier Theatre in London, which ran from October to December 1998. Rickman appeared in Victoria Wood with All the Trimmings (2000), a Christmas special with Victoria Wood, playing an aged colonel in the battle of Waterloo who is forced to break off his engagement to Honeysuckle Weeks' character.

Rickman directed The Winter Guest at London's Almeida Theatre in 1995 and the film version of the same play, released in 1997, starring Emma Thompson and her real-life mother Phyllida Law.[40] With Katharine Viner, he compiled the play My Name Is Rachel Corrie and directed the premiere production at the Royal Court Theatre, which opened in April 2005. He won the Theatre Goers' Choice Awards for Best Director. Rickman befriended the Corrie family and earned their trust, and the show was warmly received. But the next year, its original New York production was "postponed" over the possibility of boycotts and protests from those who saw it as "anti-Israeli agit-prop". Rickman denounced "censorship born out of fear". Tony Kushner, Harold Pinter and Vanessa Redgrave, among others, criticised the decision to indefinitely delay the show. The one-woman play was put on later that year at another theatre to mixed reviews, and has since been staged at venues around the world.[41]

In 2009, Rickman was awarded the James Joyce Award by University College Dublin's Literary and Historical Society.[28] In October and November 2010, Rickman starred in the eponymous role in Henrik Ibsen's John Gabriel Borkman at the Abbey Theatre, Dublin alongside Lindsay Duncan and Fiona Shaw.[42] The Irish Independent called Rickman's performance breathtaking.[43]

Rickman again appeared as Severus Snape in the final instalment in the Harry Potter series, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2 (2011). Throughout the series, his portrayal of Snape garnered widespread critical acclaim.[44] Kenneth Turan of the Los Angeles Times said Rickman "as always, makes the most lasting impression",[45] while Peter Travers of Rolling Stone magazine called Rickman "sublime at giving us a glimpse at last into the secret nurturing heart that ... Snape masks with a sneer."[46]

Media coverage characterised Rickman's performance as worthy of nomination for an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor.[47] His first award nominations for his role as Snape came at the 2011 Alliance of Women Film Journalists Awards, 2011 Saturn Awards, 2011 Scream Awards and 2011 St. Louis Gateway Film Critics Association Awards in the Best Supporting Actor category.[48]

In November 2011, Rickman opened in Seminar, a new play by Theresa Rebeck, at the John Golden Theatre on Broadway.[49] Rickman, who left the production in April, won the Broadway.com Audience Choice Award for Favorite Actor in a Play[50] and was nominated for a Drama League Award.[51] Rickman starred with Colin Firth and Cameron Diaz in Gambit (2012) by Michael Hoffman, a remake of the 1966 film.[52] In 2013, he played Hilly Kristal, the founder of the East Village punk-rock club CBGB, in the CBGB film with Rupert Grint.[53]

In the media

Rickman was chosen by Empire as one of the 100 Sexiest Stars in film history (No. 34) in 1995 and ranked No. 59 in Empire's "The Top 100 Movie Stars of All Time" list in October 1997. In 2009 and 2010, he was ranked once again as one of the 100 Sexiest Stars by Empire, both times placing No. 8 out of the 50 actors chosen. He was elected to the council of the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA) in 1993; he was subsequently RADA's vice-chairman and a member of its artistic advisory and training committees and development board.[54]

Rickman was voted No. 19 in Empire magazine's Greatest Living Movie Stars over the age of 50 and was twice nominated for Broadway's Tony Award as Best Actor (Play); in 1987 for Les Liaisons Dangereuses and in 2002 for a revival of Noël Coward's Private Lives. The Guardian named Rickman as an "honourable mention" in a list of the best actors never to have received an Academy Award nomination.[55]

Two researchers, a linguist and a sound engineer, found "the perfect [male] voice" to be a combination of Rickman's and Jeremy Irons' voices based on a sample of 50 voices.[56] The BBC states that Rickman's "sonorous, languid voice was his calling card—making even throwaway lines of dialogue sound thought-out and authoritative."[57] In their vocal range exercises in studying for a GCSE in drama, he was singled out by the BBC for his "excellent diction and articulation".[58]

Rickman featured in several musical works, including a song composed by Adam Leonard entitled "Not Alan Rickman".[59] Credited as 'A Strolling Player' in the sleeve notes, the actor played a "Master of Ceremonies" part, announcing the various instruments at the end of the first part of Mike Oldfield's Tubular Bells II (1992) on the track "The Bell".[60] Rickman was one of the many artists who recited Shakespearian sonnets on the album When Love Speaks (2002), and also featured prominently in a music video by Scottish rock band Texas entitled "In Demand", which premiered on MTV Europe in August 2000.[61]

Personal life

In 1965, at age 19, Rickman met 18-year-old Rima Horton, who became his girlfriend and would later be a Labour Party councillor on the Kensington and Chelsea London Borough Council (1986–2006) and an economics lecturer at Kingston University.[62][63] In 2015, Rickman confirmed that they had married in a private ceremony in New York City in 2012. They lived together from 1977 until Rickman's death. The two had no children.[64]

Rickman was an active patron of the research foundation Saving Faces[65] and honorary president of the International Performers' Aid Trust, a charity that works to fight poverty amongst performing artists all over the world.[66] When discussing politics, Rickman said he "was born a card-carrying member of the Labour Party."[29]

Rickman was the godfather of fellow actor Tom Burke.[67] Rickman's brother Michael is a Conservative Party district councillor in Leicestershire.[68]

Illness and death

In August 2015, Rickman suffered a minor stroke, which led to the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer.[3][69] He revealed the fact that he had terminal cancer to only his closest confidants.[70] On 14 January 2016, Rickman died in London at age 69.[71] His remains were cremated on 3 February 2016 in the West London Crematorium in Kensal Green. His ashes were given to his wife, Rima Horton. His final two films, Eye in the Sky and Alice Through the Looking Glass, were dedicated to his memory, as was The Limehouse Golem, which would have been his next project.[72] His last recorded work prior to his death was for a short video to help Oxford University students raise funds and awareness of the refugee crisis for Save the Children and Refugee Council.[73]

Tributes

Soon after his death his fans created a memorial underneath the "Platform 9¾" sign at London King's Cross railway station.[74] His death has been compared to that of David Bowie, a fellow English cultural figure who died at the same age as Rickman four days earlier, also from cancer, and kept private from the public.[75][76]

Tributes from Rickman's co-stars and contemporaries appeared on social media following the announcement; since his cancer was not publicly known, some—like Ralph Fiennes, who "cannot believe he is gone," and Jason Isaacs, who was "sidestepped by the awful news"—expressed their surprise.[62] At a West End performance of the play that made him a star (Les Liaisons Dangereuses), he was remembered as “a great man of the British theatre”.[77]

Harry Potter creator J. K. Rowling called Rickman "a magnificent actor and a wonderful man." Emma Watson wrote, "I feel so lucky to have worked and spent time with such a special man and actor. I'll really miss our conversations." Daniel Radcliffe appreciated his loyalty and support: "I'm pretty sure he came and saw everything I ever did on stage both in Britain and America. He didn't have to do that."[78] Evanna Lynch said it was scary to bump into Rickman in character as Snape, but "he was so kind and generous in the moments he wasn't Snaping about."[79] Rupert Grint said, "even though he has gone I will always hear his voice."[62] Johnny Depp, who co-starred with Rickman in three Tim Burton films, commented, "That voice, that persona. There's hardly anyone unique anymore. He was unique."[80]

Kate Winslet, who gave a tearful tribute at the London Film Critics' Circle Awards, remembered Rickman as warm and generous,[81] adding, "And that voice! Oh, that voice." Dame Helen Mirren said his voice "could suggest honey or a hidden stiletto blade."[62] Emma Thompson remembered "the intransigence which made him the great artist he was—his ineffable and cynical wit, the clarity with which he saw most things, including me ... I learned a lot from him."[78] Colin Firth told The Hollywood Reporter that, as an actor, Rickman had been a mentor.[82] John McTiernan, director of Die Hard, said Rickman was the antithesis of the villainous roles for which he was most famous on screen.[83] Sir Ian McKellen wrote, "behind [Rickman's] mournful face, which was just as beautiful when wracked with mirth, there was a super-active spirit, questing and achieving, a super-hero, unassuming but deadly effective."[78] Writer/Director Kevin Smith told a tearful 10-minute story about Rickman on his Hollywood Babble On podcast. Rickman's family offered their thanks "for the messages of condolence."[84]

Filmography

Film

Television

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1978 | Romeo and Juliet | Tybalt | BBC Television Shakespeare |

| 1980 | Thérèse Raquin | Vidal | 3 episodes |

| Shelley | Clive | Episode: "Nowt So Queer" | |

| 1982 | Busted | Simon | Television film |

| Smiley's People | Mr. Brownlow | 1 episode | |

| The Barchester Chronicles | Obadiah Slope | 5 episodes | |

| 1985 | Summer Season | Croop | Episode: "Pity in History" |

| Girls on Top | Dmitri / RADA | 2 episodes | |

| 1989 | Revolutionary Witness | Jacques Roux | Television short |

| Screenplay | Israel Yates | Episode: "The Spirit of Man" | |

| 1993 | Fallen Angels | Dwight Billings | Episode: "Murder, Obliquely" |

| 1996 | Rasputin: Dark Servant of Destiny | Grigori Rasputin | Television film |

| 2002 | King of the Hill | King Philip | Voice, Episode: "Joust Like a Woman" |

| 2004 | Something the Lord Made | Alfred Blalock | Television film |

| 2010 | The Song of Lunch | He | BBC Drama Production |

Video games

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1997 | The Space Bar | My Parker / Ty Parker | Voices |

Stage

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1976 | Sherlock Holmes | Sherlock Holmes | |

| 1977 | The Devil is an Ass | Wittipol | |

| 1978 | Love's Labour's Lost | Boyet | |

| Captain Swing | Farquarson | ||

| The Tempest | Ferdinand | ||

| 1980 | Commitments | Unknown | |

| 1981 | The Seagull | Mr. Aston | |

| 1983 | The Grass Widow | Unknown | |

| Bad Language | Bob | ||

| 1985 | As You Like It | Jaques | |

| Troilus and Cressida | Achilles | ||

| 1986 | Mephisto | Hendrik Hofgen | |

| 1987 | Les Liaisons Dangereuses | Le Vicomte de Valmont | |

| 1991 | Tango at the End of Winter | Sei | |

| 1992 | Hamlet | Hamlet | |

| 1995 | The Winter Guest | Director | |

| 1998 | Antony and Cleopatra | Mark Antony | |

| 2002 | Private Lives | Elyot Chase | |

| 2006 | My Name is Rachel Corrie | Director and Editor | |

| 2008 | Creditors | Director | |

| 2010 | John Gabriel Borkman | John Gabriel Borkman | |

| 2012 | Seminar | Leonard | |

Awards and nominations

References

- "Alan Rickman: Beguiling monster who made Cherie weak at the knees". The Independent. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- "Alan Rickmman, Harry Potter and Die Hard actor, dies aged 69". BBC News. 14 January 2016. Archived from the original on 20 November 2016. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- Saul, Heather (15 January 2016). "Alan Rickman: British actor died from 'pancreatic cancer'". The Independent. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- "Alan Rickman, actor - obituary". The Telegraph. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- Profile Archived 26 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine, biography.com. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- Paton, Maureen (1996). Alan Rickman: the unauthorised biography. London: Virgin. ISBN 978-1852276300.

- “Alan Rickman & Helen McCrory: 'With us it's mostly about laughter and the odd Martini'“. The Independent. Retrieved 16 January 2020

- England & Wales births 1837–2006. Vol. 11A. p. 1224. Print.

- England & Wales deaths 1837–2007. Birth, Marriage & Death (Parish Registers). District no. 6001F. Register. no. F56C. Entry no. 094. Print.

- Solway, Diane (August 1991). "Profile: Alan Rickman". European Travel and Life. Archived from the original on 6 October 2007. Retrieved 3 October 2007.

- England & Wales births 1837–2006. Vol. 1A. p. 515. Print.

- England & Wales deaths 1837–2007. Vol. 5F. p. 247. Print.

- 1939 United Kingdom Census. 1939 Household Register. London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham, London, England; family 4, dwelling 45, lines 11–13; 1939. Print.

- White, Hilary A. (13 April 2015). "Alan Rickman – A working-class hero at the court of Versailles". The Irish Independent. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- Mackenzie, Suzie (3 January 1998). "Angel with Horns". The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on 6 October 2007. Retrieved 3 October 2007.

- "Alan Rickman: Cinema's voice of honey-smooth villainy". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- "Obituary: Alan Rickman." Archived 17 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine BBC News. 14 January 2016. Retrieved 5 June. 2016.

- England & Wales marriages 1837–2008. Vol. 5E. p. 307. Print.

- "Untitled Love Actually Interview." Archived 18 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine Alan Archives. 10 November 2003. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- Paton, Maureen (31 May 2012). Alan Rickman: The Unauthorised Biography. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4481-3264-5.

- Paton, Maureen (2003). Alan Rickman: The Unauthorised Biography. Virgin Books; 2Rev Ed edition. p. 53. ISBN 978-0753507544.

- Royal College of Art Society (12 March 2019). "Alan Rickman (1946 - 2016)".

- "THE DEVIL IN MR RICKMAN". btinternet.com. Archived from the original on 22 April 2001.

- The RCA Journal: The Alan Rickman Issues. Archived 5 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine It's Nice That. 15 January 2016. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- Child's Play: Alan Rickman's 1970 Account of Murderous Children In An Inner-London Play Park. Archived 11 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine Flashbak. 20 January 2016. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- "Interview: Evil Elegance". Alan-rickman.com. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- Interview Alan Rickman Archived 20 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, abouthp.free.fr. Retrieved 20 December 2007.

- Staff (14 January 2016). "British actor Alan Rickman dies aged 69". RTÉ.ie. Raidió Teilifís Éireann. Archived from the original on 15 January 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- Shoard, Catherine (14 January 2016). "Alan Rickman, giant of British screen and stage, dies at 70". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- “Greatest Villains of All Time”. Empire. Retrieved 24 February 2019

- Rich, Frank (1 May 1987). "Stage: Carnal abandon in Les Liaisons Dangereuses". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- Brooks, Katherine (14 January 2016). "Alan Rickman Was A Great Film Actor, But He Was A Master of Theater First". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 15 January 2016. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- "Alan Rickman". Television Academy. Archived from the original on 17 October 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- "Alan Rickman: A Life in Pictures Highlights". BAFTA Guru. Archived from the original on 26 December 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- The Screening Room's Top 10 British Villains Archived 24 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine, CNN. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- McFerran, Ann (9 August 1991). "Alan Rickman: Villain". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- "Alan Rickman, Obituary". The Sydney Morning Herald. 16 January 2016. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- Berman, Craig (16 July 2007). "Is Potter's foe, Severus Snape, good or evil?". TODAY. Archived from the original on 28 January 2016. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- Coveney, Michael (14 January 2016). "Alan Rickman obituary". The Guardian. London, UK. Archived from the original on 14 January 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- "Film: Em and Phyllida keep it in the family". The Independent. 15 January 2015. Archived from the original on 5 December 2017. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- Bernstein, Adam (14 January 2016). "Alan Rickman, actor who brought dynamic menace to Die Hard and Harry Potter, dies at 69". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 14 January 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- "Abbey Theatre – Amharclann na Mainistreach". Abbeytheatre.ie. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- Staff (17 October 2010). "Stars set stage alight in Ibsen's dark tale". The Irish Independent. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- Singh, Anita (7 July 2011). "Daniel Radcliffe: Alan Rickman deserves Oscar nomination for Severus Snape". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 2 April 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- Turan, Kenneth (13 July 2011). "Movie review: 'Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows — Part 2'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 12 August 2011. Retrieved 13 September 2011.

- Travers, Peter (13 July 2011). "Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Part 2". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 14 September 2011. Retrieved 13 September 2011.

- Schwartz, Terri (9 November 2011). "'Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows' For Your Consideration Oscars Ad Launched". MTV. Archived from the original on 11 November 2011. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

Lukac, Michael (15 July 2011). "Harry Potter: Alan Rickman Destined for Oscar Nomination?". International Business Times. Archived from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2016. - "Alliance of Women Film Journalists Awards 2011". Movie City News. Archived from the original on 4 January 2012. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- Brantley, Ben (20 November 2011). "Shredding Egos, One Semicolon at a Time – 'Seminar' by Theresa Rebeck, a review". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 November 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- Brantley, Ben (15 May 2012). "Alan Rickman's Broadway.com Audience Choice Award Win Brings Back Memories of a 'Very Good Time' in Seminar". Broadway.com. Archived from the original on 18 June 2013. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- Brantley, Ben (24 April 2012). "2012 Drama League Award Nominations Announced!". Broadwayworld.com. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- "A Caper by the Coens, With a Fake Monet". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 February 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- Kit, Borys (12 September 2012). The New York Times (ed.). "Alan Rickman to Play CBGB Founder in Biopic". Archived from the original on 31 August 2012. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

- Staff (14 January 2016). "Alan Rickman, 1946–2016". Royal Academy of Dramatic Art. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- Singer, Leigh (19 February 2009). "Oscars: the best actors never to have been nominated". The Guardian. London, UK. Archived from the original on 27 September 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- "Formula 'secret of perfect voice'". BBC News. 30 May 2008. Archived from the original on 31 July 2010. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- "A Tribute to Alan Rickman, beloved actor and director". Iowa State Daily. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- "Using your voice". BBC. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- "Leonardism (2007)". Themessagetapes.com (Adam Leonard's website). 12 October 2010. Archived from the original on 11 February 2011. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- "Tubular Bells II". Tubular.net. Archived from the original on 11 May 2008. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- "Biography of Alan Rickman". Dominic Wills/Talktalk.co.uk. Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- Shoard, Catherine; Spencer, Liese; Wiegand, Chris; Groves, Nancy; Beaumont-Thomas, Ben (14 January 2016). "'We are all so devastated': acting world pays tribute to Alan Rickman". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 14 January 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- McGlone, Jackie (31 July 2006). "A man for all seasons". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. Archived from the original on 9 March 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- Chiu, Melody (23 April 2015). "Alan Rickman and Longtime Love Rima Horton Secretly Wed 3 Years Ago". People. Archived from the original on 14 January 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- Staff (14 January 2016). "Farewell to our wonderful patron, Alan Rickman". Saving Faces. Archived from the original on 24 January 2017. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- Rickman, Alan. "A message from the President". IPAT. Archived from the original on 26 February 2016. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- Amer, Matthew (26 July 2012). "My place: Tom Burke". Official London Theatre. Archived from the original on 23 December 2015. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- “Councillor Michael Rickman”. harborough.gov.uk.

- Friedman, Roger (15 January 2016). "Source: Alan Rickman Had Pancreatic Cancer, And Not For Very Long– Came to NY in December". Showbiz411. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- Friedman, Roger (15 January 2016). "Source: Alan Rickman Had Pancreatic Cancer, And Not For Very Long – Came to NY in December". Showbiz411. Archived from the original on 16 January 2016. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- Itzkoff, Dave; Rogers, Katie (14 January 2016). "Alan Rickman, Watchable Villain in Harry Potter and Die Hard, Dies at 69". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 December 2016. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- Ritman, Alex (9 September 2016). "Toronto: Producer Stephen Woolley Talks Dedicating 'Limehouse Golem' to Alan Rickman". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- Saul, Heather. "Alan Rickman was helping students raise money for refugees just weeks before his death". Independent. Independent. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- Gettell, Oliver (14 January 2016). "Harry Potter fans honor Alan Rickman at Platform 93⁄4". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 15 January 2016. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- Forrester, Katy (14 January 2016). "Alan Rickman died at the same age as Bowie at 69 also after battle with cancer". Daily Mirror. Archived from the original on 27 December 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- Cavna, Michael (15 January 2016). "David Bowie and Alan Rickman shared this one profoundly simple gift". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- "West End stars pay tribute to 'great' Alan Rickman at play that forged his movie career". London Evening Standard. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- Park, Andrea (14 January 2016). "Stars mourn Alan Rickman on social media". CBS News. Archived from the original on 17 January 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- Lynch, Evanna [@Evy_Lynch] (14 January 2016). "I'll also never forget how scary it was to accidentally bump into him as Snape ..." (Tweet). Retrieved 14 January 2016 – via Twitter.

Lynch, Evanna [@Evy_Lynch] (14 January 2016). "Am not prepared for a world without Alan Rickman ..." (Tweet). Retrieved 14 January 2016 – via Twitter. - "Depp Pays Tribute To 'Unique Talent' Rickman". MSN. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- Shahrestani, Vin (18 January 2016). "Kate Winslet tearfully remembers Alan Rickman at awards". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 21 January 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- Westbrook, Caroline (20 January 2016). "Colin Firth pays touching tribute to Alan Rickman, saying he was 'in awe' of the actor". Metro. Archived from the original on 22 January 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- McTiernan, John (19 January 2016). "Die Hard Director John McTiernan on Alan Rickman: 'He Had a Gift for Playing Terrifying People'". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 23 January 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- Innes, Sheila (5 January 2016). "Thanks for the tributes". LinkedIn (Sheila Innes). Retrieved 28 July 2016.

Owen, David W. (15 January 2016). "Brother is left 'broken' by Alan Rickman's death". Leicester Mercury. Archived from the original on 19 March 2016. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Alan Rickman |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alan Rickman. |

| Library resources about Alan Rickman |

| By Alan Rickman |

|---|

- Alan Rickman on IMDb

- Alan Rickman at Find a Grave

- Alan Rickman at the Internet Broadway Database

- Alan Rickman at the TCM Movie Database

- Alan Rickman at AllMovie

- Alan Rickman at Emmys

- Alan Rickman at Aveleyman

- Alan Rickman news and commentary on The Independent