Francis Ronalds

Sir Francis Ronalds FRS (21 February 1788 – 8 August 1873) was an English scientist and inventor, and arguably the first electrical engineer.[1] He was knighted for creating the first working electric telegraph over a substantial distance.[2][3] In 1816 he laid an eight-mile length of iron wire between wooden frames in his mother's garden and sent pulses using electrostatic generators.

Sir Francis Ronalds FRS | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Sir Francis Ronalds painted in 1867 | |

| Born | 21 February 1788 City of London, England |

| Died | 8 August 1873 (aged 85) Battle, East Sussex, England |

| Known for | Electric telegraph Continuously recording camera Perspective drawing instruments |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics, Electrical engineering, Applied mechanics, Meteorology, Photography, Archaeology |

Upbringing and family

Born to merchants Francis Ronalds and Jane (née Field) at their cheese-monger business in Upper Thames Street, London, he attended Unitarian minister Eliezer Cogan's school before being apprenticed to his father at the age of 14 through the Drapers' Company.[4] He ran the large business for some years. The family later resided in Canonbury Place and Highbury Terrace, both in Islington, at Kelmscott House in Hammersmith, Queen Square in Bloomsbury, at Croydon, and on Chiswick Lane.[5]

Several of Ronalds' eleven brothers and sisters also led noteworthy lives. His youngest brother Alfred authored the classic book The Fly-fisher's Entomology (1836) before migrating to Australia and their brother Hugh was one of the founders of the city of Albion in the American Midwest. His sisters married Samuel Carter[6] – a railway solicitor and MP – and sugar-refiner Peter Martineau, the son of Peter Finch Martineau. Another sister Emily epitomised the family's interest in social reform through her collaborations with early socialists Robert Owen and Fanny Wright.

Nurseryman Hugh Ronalds was his uncle, and his nephews included chemistry professor Edmund Ronalds, artist Hugh Carter,[7] barrister John Corrie Carter and timber merchant and benefactor James Montgomrey. Thomas Field Gibson, a Royal Commissioner for the Great Exhibition of 1851, was one of his cousins.

Early electrical science and engineering

Ronalds was conducting electrical experiments by 1810: those on atmospheric electricity were outlined in George Singer's text Elements of Electricity and Electro-Chemistry (1814).[8] He published his first papers in the Philosophical Magazine in 1814 on the properties of the dry pile, a form of battery that his mentor Jean-André Deluc helped to develop. The next year he described the first electric clock.[9]

Other inventions in this early period included an electrograph to record variations in atmospheric electricity through the day; an influence machine that generated electricity with minimal manual intervention; and new forms of electrical insulation, one of which was announced by Singer.[1][5] He was also already creating what would become the renowned Ronalds Library[10] of electrical books and managing his collection with perhaps the first practical card catalogue.[11]

His theoretical contributions included an early delineation of the parameters now known as electromotive force and current; an appreciation of the mechanism by which dry piles generated electricity; and the first description of the effects of induction in retarding electric signal transmission in insulated cables.[1][5][12]

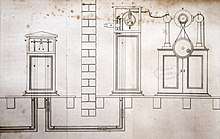

Electric telegraph

Ronalds' most remembered work today is the electric telegraph he created at the age of 28. He established that electrical signals could be transmitted over large distances with eight miles of iron wire strung on insulators on his mother's lawn in Hammersmith. He found that the signal travelled immeasurably fast from one end to the other (but still believed the speed was finite).[13] Foreshadowing both a future electrical age and mass communication, he wrote:

electricity, may actually be employed for a more practically useful purpose than the gratification of the philosopher's inquisitive research… it may be compelled to travel ... many hundred miles beneath our feet ... and ... be productive of ... much public and private benefit ... why ... add to the torments of absence those dilatory tormentors, pens, ink, paper, and posts? Let us have electrical conversazione offices, communicating with each other all over the kingdom ... give me materiel enough, and I will electrify the world.[13]

He complemented his vision with a working telegraph system built in and under his mother's garden at Hammersmith.[14] It was infamously rejected on 5 August 1816 by Sir John Barrow, Secretary at the Admiralty, as being "wholly unnecessary".[15] Commercialisation of the telegraph only began two decades later in the UK, led by William Fothergill Cooke and Charles Wheatstone, who both had links to Ronalds' earlier work.[14][16]

Grand Tour

The period 1818–20 was Ronalds' "Grand Tour" to Europe and the Near East. Embarking on his trip alone, he met up with numerous people along the way, including his friend Sir Frederick Henniker,[17] archaeologist Giovanni Battista Belzoni, artist Giovanni Battista Lusieri, merchant Walter Stevenson Davidson,[18] Revd George Waddington, Italian numismatist Giulio Cordero di San Quintino and Spanish geologist Carlos de Gimbernat. Ronalds' travel journal and sketches have been published on the web.[19] On his return, he published his atmospheric electricity observations made in Palermo, Sicily, and near the erupting crater of Vesuvius.[13]

Mechanical design and manufacture

Ronalds next focused on mechanical and civil engineering and design. Two surveying tools he designed and used to aid the production of survey plans were a modified surveyor's wheel that recorded distances travelled in graphical form and a double-reflecting sector to draw the angular separation of distant objects. He also invented a forerunner to the fire finder patented in 1915 to pinpoint the location of a fire and various accessories for the lathe. Some of these devices were manufactured for sale by toolmaker Holtzapffel.[5] There is some evidence to suggest that he assisted Charles Holtzapffel in the early stages of preparing the Holtzapffel family's renowned treatise on turning.

Perspective machines and tripod stand

On 23 March 1825, he patented two drawing instruments for producing perspective sketches.[20] The first produced a perspective view of an object directly from drawings of the plan and elevations. The second machine enabled a scene or person to be traced from life onto paper with considerable precision; he and Dr Alexander Blair used it to document the important Neolithic monuments at Carnac, France, with "almost photographic accuracy".[21][22] He also created the ubiquitous portable tripod stand with three pairs of hinged legs to support his drawing board in the field. He manufactured these instruments himself and several hundred of them were sold.[5] One of his first customers was mining engineer John Taylor.

In 1840, he applied his understanding of perspective in developing more complex apparatus to aid the accurate depiction of cylindrical panoramas, which were a popular exhibition at that time.[5]

Kew Observatory

Ronalds set up the Kew Observatory for the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1842 and he remained Honorary Director of the facility until late 1853. It was through the quality of his achievements there that Kew survived its early years and it went to become one of the most important meteorological and geomagnetic observatories in the world. This was despite ongoing efforts by George Airy, Director of the Greenwich Observatory, to undermine the work at Kew.[23]

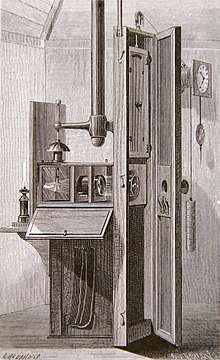

Continuously recording camera

Ronalds' most noteworthy innovation at Kew, in 1845, was the first successful camera to make continuous recordings of an instrument 24 hours per day.[24] The British Prime Minister Lord John Russell gave him a financial award in recognition of the importance of the invention for observational science.[25]

He applied his technique in electrographs to observe atmospheric electricity, barographs and thermo-hygrographs to monitor the weather, and magnetographs to record the three components of geomagnetic force. The magnetographs were used by Edward Sabine in his global geomagnetic survey while the barograph and thermo-hygrograph were employed by the new Met Office to assist its first weather forecasts. Ronalds also supervised the manufacture of his instruments for other observatories around the world (the Radcliffe Observatory under Manuel John Johnson and the Colaba Observatory in India are two examples) and some continued in use until late in the 20th century.[5]

Meteorological instruments and observations

Further instruments created at Kew included an improved version of Regnault's aspirated hygrometer that was employed for many years; an early meteorological kite; and the storm clock used to monitor rapid changes in meteorological parameters during extreme events.[23]

To observe atmospheric electricity, Ronalds created a sophisticated collecting apparatus with a suite of electrometers; the equipment was later manufactured and sold by London instrument-makers. A dataset of five years' duration was analysed and published by his observatory colleague William Radcliffe Birt.[26]

The phenomenon now known as geomagnetically induced current was observed on telegraph lines in 1848 during the first sunspot peak after the network began to take shape. Ronalds endeavoured to employ his atmospheric electricity equipment and magnetographs in a detailed study to understand the cause of the anomalies but had insufficient resources to complete his work.[5]

Last years

Ronalds' final foreign sojourn in 1853–1862 was to northern Italy, Switzerland and France, where he assisted other observatories in building and installing his meteorological instruments and continued collecting books for his library. Some of his ideas documented in this period concerned electric lighting and a combined rudder and propeller for ships that was honed in the 20th century.

He died at Battle, near Hastings, aged 85, and is buried in the cemetery there.[27][28] The Ronalds Library was bequeathed to the newly formed Society of Telegraph Engineers (soon to become the Institution of Electrical Engineers and now the Institution of Engineering and Technology) and its accompanying bibliography was reprinted by Cambridge University Press in 2013.[29]

Ronalds had a very modest and retiring nature and did little to publicise his work through his life.[30] During his last years, however, his key accomplishments became well known and revered in the scientific community, aided in particular by his friends Josiah Latimer Clark and Edward Sabine and his brother-in-law Samuel Carter. He was knighted at the age of 82. Colleagues at the Society of Telegraph Engineers regarded him as "the father of electric telegraphy",[31] while his continuously recording camera was noted to be "of extreme importance to meteorologists and physicists, and… employed in all first-rate observatories".[32] His portrait was painted by Hugh Carter.[33] Commemorative plaques have been installed on two of his former homes[34] and a road was named after him in Highbury.

References

- Ronalds, B.F. (July 2016). "Francis Ronalds (1788–1873): The First Electrical Engineer?". Proceedings of the IEEE. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2016.2571358.

- Appleyard, R. (1930). Pioneers of Electrical Communication. Macmillan.

- Norman, Jeremy. "Francis Ronalds Builds the First Working Electric Telegraph (1816)". HistoryofInformation.com. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- "Francis Ronalds". Dictionary of Unitarian and Universalist Biography. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- Ronalds, B.F. (2016). Sir Francis Ronalds: Father of the Electric Telegraph. London: Imperial College Press. ISBN 978-1-78326-917-4.

- "Carter, Samuel (1805–1878), lawyer". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- "Carter, Hugh (DNB12)". Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- Singer, G.J. (1814). Elements of Electricity and Electro-Chemistry. London: Longman.

- Ronalds, B.F. (June 2015). "Remembering the First Battery-Operated Clock". Antiquarian Horology. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- "Welcome to the IET Archives". IET. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- James, M.S. (1902). "The Progress of the Modern Card Catalog Principle". Public Libraries.

- Ronalds, B.F. (February 2016). "The Bicentennial of Francis Ronalds's Electric Telegraph". Physics Today. doi:10.1063/PT.3.3079.

- Ronalds, Francis (1823). Descriptions of an Electrical Telegraph and of some other Electrical Apparatus. London: Hunter.

-

Ronalds, Beverley Frances, Sir Francis Ronalds: Father Of The Electric Telegraph, p. 142, World Scientific, 2016 ISBN 1783269197.

- Ronalds, B.F. (2016). "Sir Francis Ronalds and the Electric Telegraph". Int. J. for the History of Engineering & Technology. doi:10.1080/17581206.2015.1119481.

- "This Month in Physics History – August 5, 1816: Sir Francis Ronalds' telegraph design rejected". American Physical Society. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- Frost, A.J. (1880). "Biographical Memoir of Sir Francis Ronalds, F.R.S.". Catalogue of Books and Papers Relating to Electricity, Magnetism, the Electric Telegraph, &c including The Ronalds Library. London: Spon.

- "Henniker, Frederick (DNB00)". Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- "Davidson, Walter Stevenson (1785–1869)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- "Sir Francis Ronalds' Grand Tour". Sir Francis Ronalds and his Family. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- "Perspective Drawing Instruments". Sir Francis Ronalds and his Family. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

- Bailloud, G.; et al. (2009). Carnac: Les Premières Architectures de Pierre. Paris: CNRS.

- Blair and Ronalds (1836). "Sketches at Carnac (Brittany) in 1834". Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- Ronalds, B. F. (June 2016). "Sir Francis Ronalds and the Early Years of the Kew Observatory". Weather. doi:10.1002/wea.2739.

- Tissandier, G. (1876). A History and Handbook of Photography.

- Ronalds, B. F. (2016). "The Beginnings of Continuous Scientific Recording using Photography: Sir Francis Ronalds' Contribution". European Society for the History of Photography. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- Birt, W.R. (1850). "Report on the Discussion of the Electrical Observations at Kew". Report of the British Association for 1849.

- "Ronalds Family Vault". Sir Francis Ronalds and his Family. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- Ronalds, B.F. (2018). "The Ronalds–Carter Family in 19th-Century Battle" (PDF). Collectanea, Battle and District Historical Society. O1.12.

- Frost, A.J. (2013). Catalogue of Books and Papers Relating to Electricity, Magnetism, the Electric Telegraph, &c. including The Ronalds Library, compiled by Sir Francis Ronalds, F.R.S. Cambridge University Press.

- Sime, J. (1893). Sir Francis Ronalds, F.R.S. and his Work in Connection with Electric Telegraphy in 1816. London.

- "Second Annual Meeting". Journal of the Society of Telegraph Engineers. 2. 1873.

- "Ronalds, Francis (DNB00)". Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- "Sir Francis Ronalds". National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- "Sir Francis Ronalds". London Remembers. Retrieved 5 October 2016.