Rhododendron maximum

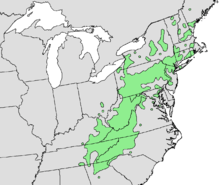

Rhododendron maximum — its common names include great laurel,[2] great rhododendron, rosebay rhododendron, American rhododendron and big rhododendron — is a species of Rhododendron native to the Appalachians of eastern North America, from Alabama north to coastal Nova Scotia.

| Rhododendron maximum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Flower cluster | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Ericales |

| Family: | Ericaceae |

| Genus: | Rhododendron |

| Subgenus: | Rhododendron subg. Hymenanthes |

| Section: | Rhododendron sect. Ponticum |

| Species: | R. maximum |

| Binomial name | |

| Rhododendron maximum | |

| |

Description

Rhododendron maximum is an evergreen shrub growing to 4 m (13 ft), rarely 10 m (33 ft), tall. The leaves are 9–19 cm (3–8 in) long and 2–4 cm (0.75-1.5 in) broad.[3] The flowers are 2.5–3 cm (1 in) diameter, white, pink or pale purple, often with small greenish-yellow spots. The fruit is a dry capsule 15–20 mm (.60-.79 in) long, containing numerous small seeds. The leaves can be poisonous. Leaves are sclerophyllous, simple, alternate, and oblong (10 to 30 cm long, 5 to 8 cm wide). It retains its waxy, deep-green leaves for up to 8 years, but once shed are slow to decompose. It produces large, showy, white to purple flowers each June and July.[3]

Range

Rosebay rhododendron is the most frequently occurring and dominant species of Rhododendron in the southern Appalachian region,[4] and occurs occasionally on mesic hill-slopes throughout the upper Piedmont Crescent of the Southeastern United States.

Ecology

Approximately 12,000 square miles in the southern Appalachians are occupied by this species[5] where it dominates the understory. This species has historically been confined to riparian areas and other mesic sites but takes advantage of disturbed areas where it is present to advance onto sub-mesic sites. It prefers deep well-drained acid soils high in organic matter where it produces a thick, peat-like humus. It prefers low to medium light conditions for optimum carbon gain, and has a tremendous capacity for avoiding cavitation during freeze-thaw cycles.[6] Where extensive overstory mortality has eliminated most of the overstory, this species forms a thick and continuous subcanopy known locally as ‘laurel slicks’ or ‘laurel hells’. Rosebay rhododendron is an important structural and functional component of southern Appalachian forest ecosystems. What isn’t clear is whether or not we are in a period of advancement or retreat for this species. For example, on poorly drained sites on ridge or upper slope positions, large areas of rosebay rhododendron, particularly at the high elevations, have recently died out presumably due to the Phytophthora fungus, or due to recent prolonged periods of below-average precipitation. Yet, rosebay rhododendron now occupies sites that historically were free of evergreen understory. There are still important questions to be answered regarding this species to completely understand its role in forest understories.

Reproduction

Rosebay rhododendron is clonal. It is capable, however, of reproducing both vegetatively and sexually. It reproduces vegetatively through a process called ‘layering’ where it produces roots from above ground woody parts when in contact with the forest floor. The fruit is produced from showy flowers from March to August. The fruit is an oblong capsule that ripens in the fall, and splits along the sides soon after ripening to release large numbers of minute seed (approx. 400 per capsule).[7] Microsite requirements for seed germination are relatively specific (e.g., high in organic matter such as rotting logs); hence, the majority of reproduction is vegetative resulting in a clonal distribution.

Growth and management

Seeds from rosebay rhododendron are minute and it is estimated that approximately 11 million are contained in 1 kg. Commercial seed production is generally from cultivated hybrids. Seeds from wild sources are not commonly sold commercially. Rosebay rhododendron is a slow-growing shrub and has a very high sprout potential. If mechanical removal is attempted in the case of forest management, extremely high densities are attained by this species in a matter of a few years. Prescribed fire has also been used to control this species but with limited success.[8]

Benefits

Rosebay rhododendron is a striking and aesthetically pleasing feature of mesic southern Appalachian forests. It is one of the largest and hardiest rhododendrons grown commercially. Several cultivars with white to purple flowers have been selected for the horticultural trade.[9] Where it occurs naturally, it produces a showy, white, pink, or light purple flower primarily in June, but occurs from March into August. Rosebay rhododendron maintains deep-green foliage year round. This species affords protection to steep watersheds and shelter for wildlife. The wood is very hard and is occasionally used for specialty wood products.

Detrimental effects

For all its prized qualities as a naturally occurring component of the landscape or as plantings in residential and commercial landscaping, rosebay rhododendron can have an inhibitory effect on regeneration of other plant species. There is some evidence to suggest that due to fire suppression and the absence of other cultural activities (i.e., mountain-land grazing), this species has advanced beyond the mesic forest sites into sub-mesic understories.[10] The significance of this movement onto previously unoccupied sites centers around the impacts of rosebay rhododendron on plant succession[11] and resource availability.[12] Rosebay rhododendron is associated with reduced woody and herbaceous seedling abundance throughout its range, and hence poses a serious impediment to the production of wood products. The mechanism(s) by which rosebay rhododendron reduces seedling survival has been the subject of much debate. Possible sources of inhibition include allelopathy, competition for resources including light, physical and chemical attributes of the forest floor and soil, and interactions between some or all sources.[13][12]

Alternate common names

R. maximum has also been called:

- Great rhododendron

- Late rhododendron

- Summer rhododendron

- Great laurel

- Bigleaf laurel

- Deertongue laurel

- Rose tree

- Rose bay

- Bayis

- Mountain laurel

Symbolism

Rhododendron maximum is the state flower of the U.S. state of West Virginia.

See also

- Catawbiense hybrid – R.catawbiense & R.maximum hybrids

- Central and southern Appalachian montane oak forest

- List of Rhododendron species

References

- Botanic Gardens Conservation International (BGCI).; IUCN SSC Global Tree Specialist Group. (2018). "Rhododendron maximum". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T82889952A135956342. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T82889952A135956342.en. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- "Rhododendron maximum". Natural Resources Conservation Service PLANTS Database. USDA. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- "Rhododendron maximum". Missouri Botanical Garden. Retrieved 2019-08-27.

- Swanson, R. E. (1994). A Field Guide to the Trees and Shrubs of the Southern Appalachians. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 399.

- Dobbs, M. M. (1995). Spatial and temporal distribution of the evergreen understory in the southern Appalachians (M. Sci. Thesis). Athens, GA: University of Georgia. p. 100.

- Lipp, C. C.; Nilsen, E. T. (1997). "The impact of subcanopy light environment on the hydraulic vulnerability of Rhododendron maximum to freeze-thaw cycles and drought". Plant, Cell and Environment. 20: 1.264–1.272.

- Schopmeyer, C. S. (1974). Seeds of woody plants in the United States. Agricultural Handbook No. 45Q. USDA Forest Service. p. 883.

- Clinton, B. D.; Vose, J. M. (2000). "Plant succession and community restoration following felling and burning in the southern Appalachian Mountains". In W. K. Moser & C. F. Moser (ed.). Fire and forest ecology: innovative silviculture and vegetation management. Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference Proceedings. 21. Tallahassee, FL: Tall Timbers Research Station. pp. 22–29.

- Brown, C. L.; Kirkman, L. K. (1990). Trees of Georgia and Adjacent States. Portland, OR: Timber Press. p. 292.

- Dobbs, M. M. (1998). Written at Athens GA. Dynamics of the evergreen understory at Coweeta (PhD Dissertation). Hydrologic Laboratory, North Carolina: University of Georgia. p. 179.

- Clinton, B. D.; Vose, J. M. (1996). "Effects of Rhododendron maximum L. on Acer rubrum L. seedling establishment". Castanea. 61 (1): 38–45.

- Nilsen, E. T.; Clinton, B. D.; Lei, T. T.; Miller, K.; Semones, S. W.; Walker, J. F. (2001). "Does Rhododendron maximum L. (Ericaceae) reduce the availability of resources above and belowground for canopy tree seedlings?". American Midland Naturalist. 145: 325–343.

- Nilsen, E. T.; Walker, J. F.; Miller, O. K.; Semones, S. W.; Lei, T. T.; Clinton, B. D. (1999). "Inhibition of seedling survival under Rhododendron maximum (Ericaceae): could allelopathy be a cause?". American Journal of Botany. 86 (11): 1.597-1.605.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rhododendron maximum. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Rhododendron maximum |