Francisco Xavier de Mendonça Furtado

Francisco Xavier de Mendonça Furtado (1701–1769) served in Portugal's armed services rising in rank from soldier to sea-captain, then became a colonial governor in Brazil and finally a secretary of state in the Portuguese government. His major achievements included the extension of Portugal's colonial settlement in South America westward along the Amazon basin and the carrying out of economic and social reforms according to policies established in Lisbon.[1] [2]

Childhood

Francisco Xavier de Mendonça Furtado was born in Mercês, Lisbon on 9 October 1701 and baptised on 12 October 1701 in the Chapel of our Lady of Mercy (Portuguese: Capela de Nossa Senhora das Mercês)[3] [4] on the Travessa das Mercês.[5] His father was Manuel de Carvalho e Ataíde, a member of Portugal's armed forces and a genealogist, and his mother was Teresa Luisa de Mendonça e Melo.

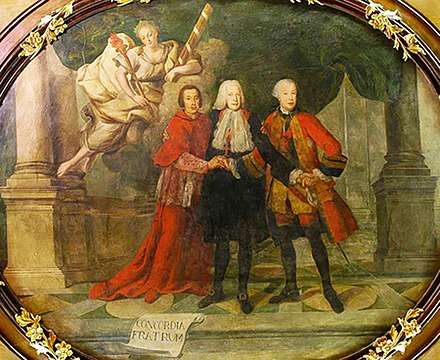

One of twelve children, his most significant siblings were Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo[6] who became King José I's Secretary of State of Internal Affairs and was elevated by the king in 1769 to the title by which he is most often referred, Marquis of Pombal (Portuguese: Marquês de Pombal), and Paulo António de Carvalho e Mendonça, a member of Lisbon's clergy who became Inquisitor-General of the Inquisition for the period 1760–1770. These three brothers were closely bonded within the family (as illustrated in this painting (left)), a relationship which was further revealed in their adulthood in the way they supported each other professionally.[7]

No information is available about Mendonça Furtado education and other activities preceding his military service apart from the record of him and his brother Paulo António de Carvalho e Mendonça being made noblemen of the royal court (Portuguese: fidalgo da Casa Real) on the same day. He was 11 years of age at that time and was using the name Francisco Xavier de Carvalho.

Speculating about his activities in early adulthood, biographer Fabiano dos Santos says, "He may have devoted himself to taking care of his family's estates … while his older brother, Sebastião José, began his diplomatic career."[8]

Military Service

On 14 April 1735 Mendonça Furtado followed his father's career and joined the armed forces where he served for 16 years rising from the rank of soldier to sea-captain.[9]

Spanish-Portuguese War

In December of the following year he was despatched as part of a campaign to defend the Portuguese settlement of Colonia del Sacramento (Portuguese: Colónia do Sacramento; English: Colony of the Holy Sacrament) from Spanish invasion in what is referred to as the Spanish–Portuguese War (1735–1737). The settlement established in 1680 was located on the northwestern shore of the Río de la Plata, directly opposite to the Spanish port of Buenos Aires on the river's southern shore, and in the Banda Oriental (or Banda Oriental del Uruguay (Eastern Bank)) region, including most of modern-day Uruguay, portions of Argentina, and of Brazil's Rio Grande do Sul and Santa Catarina.

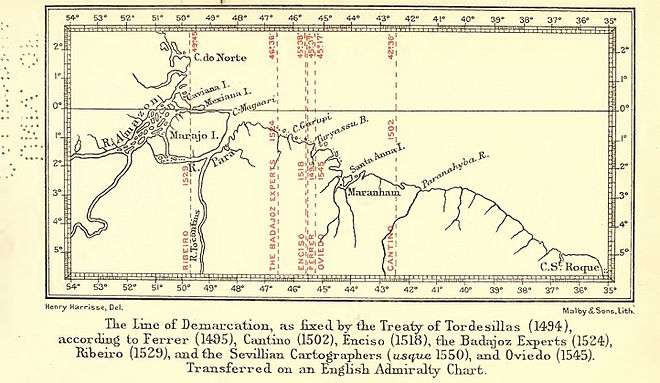

The war itself was predated by extensive struggles between Spain and Portugal regarding each empire's rightful ownership of South American territory. In theory, the matter was resolved under the Treaty of Tordesillas signed by both nations in 1494. To settle previous disputes and in anticipation of any further discoveries, the treaty made a delineation along a meridian 370 leagues (or 1100 nautical miles) west of the Cape Verde islands with Spain being entitled to lands to its west and those to the east being Portugal's.

On the South American continent, the treaty gave a tiny section to Portugal, then called "Land of the Holy Cross" (Portuguese: Terra da Santa Cruz), now the eastern part of modern-day Brazil. Observance of the treaty on the ground by both parties was another matter, with a number of causes including the fact that the meridian line was never exactly expressed in terms of longitudinal degrees, on the continent there was confusion on both sides as to where the meridian line was located, many Portuguese believed that the Amazon and Rió de la Plata estuaries were within their territory,[10] and there were deliberate intrusions by both empires into each other's territories for strategic purposes or for financial gain.[11]

Colonia del Sacramento was officially to the west of the meridian and therefore on Spanish territory, although Portugal believed otherwise. In any case Spain had paid little attention to the area by that time, and after the Portuguese settled there the population in and around the town expanded rapidly. It was soon producing goods and resources of value to Portugal. However, Portugal's primary motivator in settling there may not have come from commercial interests so much as its "strategic importance in resisting the Spanish."[12]

Spain's suspicions soon emerged and its new strategy was to place limits on Portugal's expansion in the Banda Oriental. A major step in 1724 was the expulsion of Portuguese settlers and the building of strong fortifications at Montevideo on the same side of Río de la Plata and to the east of Colonia del Sacramento. Over time, its own settlers gradually moved all the way north to the Brazilian border, often building forts in the new settlements to expand Spain's military presence.[13]

From the early days of its existence, Colonia del Sacramento passed backwards and forwards between the two empires several times, and although it was under Portuguese control when the 1735–1737 war commenced, Spain had troops on its outskirts and had set up a naval blockade on the Río de la Plata. But Portugal's massive movement of naval and military forces across the Atlantic soon broke through and by the last year Colonia del Sacramento was temporarily restored to Portugal's hands. Mendonça Furtado was involved in that action for five months.

Other military action

At the end of the war, Mendonça Furtado travelled to Rio de Janeiro from where he was despatched to Pernambuco to join forces defending the Fernando de Noronha archipelago from the French.

Ironically, although originally discovered by the Portuguese at the beginning of the 16th century and soon after occupied by them, the archipelago was progressively invaded or occupied by the English (1534), the French (1556-1612) and the Dutch (1628-1630 and again 1635-1655). The second French "occupation" began in 1736 when the islands were unoccupied and the French East India Company set up a trading post there. Portugal's military operation took place in 1737 and immediately after the French had departed, they set up permanent occupation and built several forts to strengthen their use of the islands as a way of safeguarding their shipping routes against foreign powers. Mendonça Furtado continued his involvement with that campaign until he returned to Lisbon in 1738.

From the end of that decade until 1750 he led eight military expeditions including two in the Azores and one in Tenerife, was promoted in 1741, and shortly before the end of his military career was promoted again to the rank of sea captain.

Brazil before Mendonça Furtado's appointment

Early Colonial Structures

There were sharp differences between Spain's and Portugal's approaches to colonizing new territories in their empires as illustrated, for example, Spain's approach in those territories discovered by Christopher Columbus and Portugal's use of Brazil following the early encounters by João Ramalho Maldonado, Pedro Álvares Cabral, and Pêro Vaz de Caminha, the royal clerk on Cabral's flagship who wrote to King Manuel I describing the new territory.[14]

Spain's development of its empire had been advanced rapidly by the crown creating viceroyal positions, with the earliest already in place by the middle of the 16th century. By contrast, because Portugal's expansion into Africa, India, the East Indies and Macau (see Evolution of the Portuguese Empire was driven by its desire to find resources it could use for its own financial gain and to maintain its program of international trade. Consequently, it had no interest in the social and governmental development of these regions.

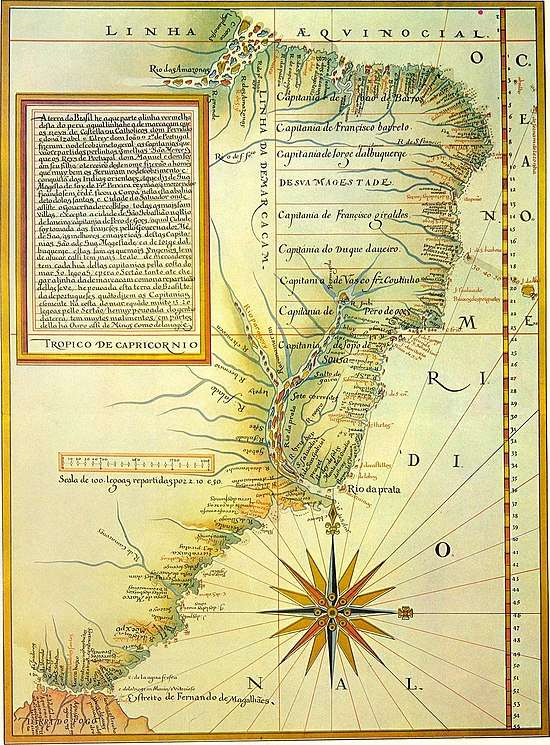

In Brazil, because in the early 16th century the crown did not have sufficient funds to establish a fully-fledged colony, Portugal's approach in 1534 was to divide the country into fifteen areas called captaincies each headed by a member of its aristocracy or nobility who as a donatário (donee or donatory) received from the crown a "letter of donation" and a "charter" which gave each the right to develop the land by investing their own money, responsibility for collecting taxes for the crown and for the Order of Christ, and the right to retain a set portion of this income for personal purposes.[15][16][17][18][19]

These land users were also given responsibility for "pacifying the indigenous peoples' resistance to Portuguese rule by incorporating them in the colonial society and economy."[20] The abiding questions are how these donatorios exercised this role and what impact it had on the indigenous population?

The majority of these donatários never lived on their land and many never visited it at all. With four exceptions, the system turned out to be disorderly, haphazard, unproductive and inefficient, and apart from expansion of the sugar industry and the exporting of Caesalpinia echinata, commonly referred to as Brazilwood in English and in Portuguese as pau-de-pernambuco and pau-brasil, taken from forests along the coast, and valued for its red dye extract and timber, little else emerged.

The overall failure of the captaincy system led King João III to respond in 1549 by creating a position of Governor General of Brazil (Portuguese: Governo-Geral do Brasil) with viceroyal status and a responsibility to report directly to the crown. To this position he appointed Tomé de Sousa who arrived in Brazil that same year and established Salvador as his capital. The captaincies continued to exist and more were created, but the role changed from its original form into a system of regional administration with each captaincy under the direct control of the governorate and therefore required to report upwards.

Further stages of development included the division twice-over of the Governor Generalate of Brazil in two to become the Governorate General of Rio de Janeiro (Portuguese: Governo-Geral do Rio de Janeiro) and the Governorate General of Bahia (Portuguese: Governo-Geral da Bahia), before in the early 17th century the Governor Generalate of Brazil was divided into two states, the State of Brazil (Portuguese: Estado do Brasil) and the State of Maranhão (Portuguese: Estado do Maranhão).

Population

Because the overall population was not fully recorded in Brazil's early colonial period, the actual numbers of native Indians, mixed-race people and migrants from Europe[21] are subject to debate.[22] One source estimates that at the end of the 17th century the assimilated population was about 300,000 of which European immigrants constituted one-third,[23] the remainder being Indians who had gained freedom from compulsory labour, former African slaves who had gained freedom, and those Indians, mostly women, who had entered into interracial marriages and the children.

Another analysis suggests that by the end of the 16th century there were about 25,000 Europeans in the yet-to-be formed Brazilian colony, that this number had grown to 50,000 by the end of the 17th century, and that during the period 1700–1720 it increased by about 5,000–6,000 per year. On a conservative estimate, therefore, this would place the population of European origin at a little more than 105,000 by the end of the second decade of the 18th century.[24]

In the early colonial period, European immigrants were the minority within the total population, while the Indian population, although never formally measured, constituted the majority having been estimated as 2.43 million in the 16th century[25][26] reduced by infectious diseases to 10% of that figure by the mid-18th century[27] As a result, the Indians were quickly outnumbered by the African slaves, of whom there were 560,000 at the end of the 17th century,[28] after which the demands for slave labour increased rapidly and between 1700 and 1800 1.7 million slaves, mostly men, were imported.

But the African slave population too was subject to deaths caused by infectious diseases. This along with their poor living conditions and diet, long working hours, and the frequent use of corporal punishment meant the death rate was very high. Additionally, the imbalance between the number of men and women in the slave community, along with the men's lack of freedom of movement, meant that the reproduction rate in this part of the population was very low and would only be reversed in the 19th century. With all these factors, including the fact that number of deaths was never recorded, it is impossible to estimate the exact size of the African slave population, and it can only be assumed that the actual numbers were high at any one time.[29]

Indigenous peoples

Use of the words "Indians" (Portuguese: "Índios" or "Índios brasileiros") as a general classification of Brazil's indigenous peoples, made sense to Europeans who had no understanding of their ethnic identity, but it also disguised the fact that there was a large number of distinct nations and tribes estimated to be about 1,000 with a total population of about 2.4 million.[30][31] They never saw themselves as one people with any common identity despite their origin having arisen from waves of migration via a land bridge from Siberia into North and then South America. Each nation and tribe had its own distinctive history, mythology, religion, language, tribal wear and customs.[32]

.png)

Brazil's original occupants were a largely semi-nomadic people who lived within their environment by subsistence and migrant agriculture. Because family and tribal identity was strong, territorial disputes between tribes and nations often led to warfare. Other characteristics included shamanism, ritual cannibalism and polygamy, and from a Christian perspective their religious beliefs were viewed as "pagan" and therefore evil. Because of these factors, early explorers and later settlers regarded these people as primitive and uncivilised.[33]

Immediately following the arrival of Europeans in Brazil came the exposure of the Indians to infectious diseases, principally smallpox, influenza and measles as well as typhus, cholera, tuberculosis, mumps, yellow fever and pertussis, to which they had no resistance. The problem was further boosted by the arrival of African slaves, and climaxed from the mid-17th to the mid-18th centuries. Epidemic outbreaks occurred spread among the Indians and the death rate is estimated to have been 90% of the entire Indian population including those who had never had direct contact with the Europeans.[34]

In the three decades prior to Mendonça Furtado's arrival, major smallpox epidemics had gone through the Grão-Pará and Maranhão region in the 1720s and 1740s, and that had been followed by a measles epidemic from the latter part of 1749 into 1750, again resulting in deaths in Belém and the surrounding regions. Both diseases killed a small number of settlers, but the decimating effect was among the Indian population where infections were transmitted quickly because no-one understood how these diseases were being transmitted.

By the early 1720s, variolation (the precursor of smallpox vaccination) was introduced into both North and South America; but public suspicion delayed its widespread use in Brazil. Indians were among the most resistant as illustrated in a failed attempt in 1729 by Carmelite missionaries in the Amazon to administer it to local Indians.

Jesuits' arrival

The Catholic Church's attitude toward American Indians emerged in an encyclical entitled Sublimis Deus (sometimes incorrectly called "Sublimis Dei") issued by Pope Paul III in 1537.[35] In it the pope observed:

"The enemy of the human race, who opposes all good deeds in order to bring men to destruction, beholding and envying this, invented a means never before heard of, by which he might hinder the preaching of God's word of Salvation to the people: he inspired his satellites who, to please him, have not hesitated to publish abroad that the Indians of the West and the South, and other people of whom We have recent knowledge should be treated as dumb brutes created for our service, pretending that they are incapable of receiving the Catholic Faith." (Sublimis Deus, par. 3.)

He then ruled that "notwithstanding whatever may have been or may be said to the contrary, the said Indians and all other people who may later be discovered by Christians, are by no means to be deprived of their liberty or the possession of their property, even though they be outside the faith of Jesus Christ." (Sublimis Deus, par. 4).

These remarks were prefaced in the encyclical by the pope's assertion that because the human race "has been created to enjoy eternal life and happiness" and that all "should possess the nature and faculties enabling [them] to receive that faith", it was not "credible that any one should possess so little understanding as to desire the faith and yet be destitute of the most necessary faculty to enable [them] to receive it." (Sublimis Deus, par. 2.) The encyclical concluded by defining the method for this task as, "the said Indians and other peoples should be converted to the faith of Jesus Christ by preaching the word of God and by the example of good and holy living." (Sublimis Deus, par. 5.)

With reports being made to the king regarding the problem of finding labour and Indian hostility, he was readily amenable to the idea of the Jesuits being involved in the colony's development, not only so the Indians could be converted to Christianity, but, more likely, so that their integration into colonial society would lead to their playing a productive role in its development and increase its contribution to Portugal's wealth.

The relationship that was set up between the Jesuits and the monarchy was known as a padroado (royal patronage) through which the crown was prepared to support their missionary work providing the other goals were being achieved at the same time.[36] Although other religious orders (especially Franciscans, Benedictines and Carmelites) went to Brazil later, especially to areas not reached by the Jesuits, they did not receive the same level of support from the monarchy and the papacy, and the Jesuits remained Brazil's dominant missionary force.

The first arrival of Jesuits included four priests and two lay brothers under the leadership of Manuel da Nóbrega (Manoel according to the old spelling)[37] who travelled to Brazil with Sousa. They began their work in the captaincy of Bahia and others soon followed, so by the end of the century Brazil had 169 Jesuits, and by their expulsion in 1759 they had grown to more than 600.

Nóbrega's immediate focus was on the protection of the Indians from cruelty and slavery, which became an immediate source of tension between the Jesuits and Portuguese landholders. From 1549 onwards, as Indians were converted to Christianity, they were offered the opportunity to live in aldeias (Literally "villages". Also called in some literature aldeamentos or aldeiamentos[38] where the Jesuits built residences, churches, schools and other facilities. As a substitute for their semi-nomadic lifestyle, the Jesuits saw these settlements as a way of stabilising Indian life, protecting them from exploitation, building their commitment to Christian belief, and establishing loyalty to the monarch.

With their numbers growing in Brazil, the Jesuits were able to extend their work over a large part of the colony's coastal areas, the forts throughout the Amazon region, and progressively south even as far as Colonia del Sacramento. Everywhere they set up new aldeias, and in major centres colleges and hospitals.

However, they soon realised that because of the Indians' strong tribal beliefs and their semi-nomadic lifestyle, converting adult Indians to Christianity and preventing them from reverting to their tribal beliefs was difficult. Over time, their studies illustrated these problems. For example, a report from Jesuit José de Anchieta y Díaz de Clavijo estimated that between 1549 and the mid–1580s about 100,000 Indians had been converted, but that only one in five had remained within the church "owing to disease, enslavement by the settlers, and their tendency to flee the aldeias";[39] and an even later report by another Jesuit Fernão Cardim covering the period 1583 to 1585 said that there were only 18,000 converts with the greatest numbers in those areas where the most Jesuits were concentrated.[40] The Jesuits' response was to concentrate their activities towards Indian children whom they found more pliable towards exploring different belief structures within an educational environment.[41]

.jpg)

As a way of enhancing their ability to communicate with the diverse, multilingual Indian population, the Jesuits developed from the 70 Tupian languages spoken by South American Indians a common language which had strong similarities to the now-extinct Old or Classical Tupi which was spoken by the Indians of south and southeast Brazil. They called it Tupi and it became a standard means of communicating with the Indians. Jesuits André Thévet and José de Anchieta translated prayers and biblical stories into the new language and later missionaries followed their example.[42]

There is an ongoing debate about how the Jesuits approached the task of converting the Indians to Christianity. Elsewhere in the world they had employed a process called mestiçagem (literally, miscegenation, accommodation or amalgamation – that is, not how the worldview of one religion could displace another, but how the concepts of one religious belief system (i.e. in Brazil, the Indians) could be 'hybridised' with those of another (for the Jesuits, their Christian beliefs) so the product was a "new" religion which communicated itself by association with or representation through the "old".)[43] The "Catholicism" which emerged in Brazil through this interactive process could be argued as being different and unique by comparison with those that emerged elsewhere.[44]

As the Jesuits tried to carry out their work in the early years, they experienced difficulties because of the settlers' cruelty towards the Indians and the fact that most of them already had Indians as slaves. As already mentioned, this had been a characteristic of the Bandeirantes, and others including those managing land through the donatário system, and the Jesuits' increasing control over the availability of Indians for the workforce led to growing tension. When the settlers appealed to the crown in 1570, King Sebastião I issued a decree that Indians "could only be enslaved in a just war declared by the king or his governor or if Indians were found guilty of cannibalism"[45] while those living in the aldeias were protected. This was based on the principle of "resgates" (literally, "ransoming"), in the sense that Indians dealt with in this way "could be made to work while they ostensibly received religious instruction. In practice, individuals reduced to this status were assigned monetary values in post-mortem estate inventories, passed on in wills as property to surviving heirs, and transferred to creditors to liquidate debts."[46]

That measure did not go far enough to satisfy the settlers' needs. Nor were the Jesuits' prepared to accept it because they could see that the settlers were ignoring the new law anyway by deliberately setting up what they saw as "just wars" under the guise of which they were able to capture Indians and force them into slavery.[47] Some Bandeirantes even raided the aldeias to capture Indians for their own use. Further appeals to the crown by both the Jesuits and the settlers led the king in 1574 to issue a further decree in which he reinforced the resgate principle but required that the names of all Indians taken into slavery should be entered into an official registry.

But the problem did not disappear. As a Jesuit report issued nearly six decades later showed:

"Also over time the poor Indians suffer great injustices from the Portuguese, which here can not be referred to extensively; likewise much unjust captivity, having sold them off the land contrary to the content of the laws of your magistracy, and by overpowering them. Others oppress them with great violence, obliging them to very heavy services, such as producing tobacco: in which some work seven and eight uninterrupted days, and at night ... and so they flee to the forests, depopulating their villages. And others in the same service die of grief without any remedy. There are many examples of all these things. "[48]

When, early in his time in Brazil. Nóbrega was aware of the extent of this problem, he quickly appealed to the king for a diocese to be set up in Brazil so a bishop's authority could be called upon to help control the settlers. The Diocese of São Salvador da Bahia was created by Pope Julius III in February 1551, Pedro Fernandes Sardinha was appointed as its first bishop and took office in June 1552.

Although the Jesuits' policy on slavery was in line with Pope Paul III's encyclical - at least as far as Indians who agreed to adopt and remain faithful to Christian belief were concerned - they appear to have kept an open mind regarding the crown's policy on "just war" and the punishment of those who reverted to tribal beliefs was concerned.[49] The controversy which still occupies modern historical debate focuses on the fact that the Jesuits themselves used both African and Indian slaves, and the evidence shows that not all these Indian had been brought into slavery according to the regulations set in place by the king.[50]

The underlying factor was that, as their volume of work increased, the Jesuits raised funds to support it by using land for the production of goods. In turn this increased their need for labour. In the process they became "Brazil's largest landowner and greatest slave-master."[51] According to Alden, the outcome was:

"Every sugar-producing captaincy possessed one or more Jesuit plantation; Bahia alone had five. From the Amazonian island of Marajo to the backlands of Piauí the Jesuits possessed extensive cattle and horse ranches. In the Amazon their annual canoe flotillas brought to Belém envied quantities of cacao, cloves, cinnamon, and sarsaparilla, harvested along the great river's major tributaries. Besides flotillas of small craft that linked producing centres with operational headquarters, the Society maintained its own frigate to facilitate communications within its far-flung network. The Jesuits were renowned as courageous pathfinders and evangelists, as pre-eminent scholars, sterling orators, as confessors of the high and mighty, and as tenacious defenders of their rights and privileges, which included licences from the crown to possess vast holdings of both urban and rural property and complete exemption of their goods from all customs duties in Portugal and in Brazil."[52]

Forced labour, slavery and genocide

Disinterested in colonizing Brazil during the approximate period of 1500 to 1530, Portugal's only focus was on extracting Brazilwood from the forests and exporting it to Europe.[53] With a lack of any Portuguese workforce in situ, attempts were made to attract Indians to provide labour, and in exchange for their work they were offered goods like mirrors, scissors, knives and axes.

By 1534 the captaincies had been set up and industries such as sugar and cotton began to develop. The captains' expectations were that the Indians would be a source of low-cost labour, and this had been spelt out by João III who said that labour could be gained either by negotiation or enslavement, and that a captain even had the entitlement to ship up to twenty-four slaves per year to Lisbon.

The Indians, not carrying a European mindset of long-term commitment to labour as a means of living, continued to come and go as they pleased. Additionally, because the classifications of work were divided in Indian society according to a gender-based system, much of the work was viewed as suitable only to women. With no understanding among settlers of how this system worked, and with a growing desire to maximise their profits, coercion began to displace negotiation as a means by which labour would be found.

In addition, as they saw their land being taken over and their freedom limited, hostility towards the settlers arose among the Indians. In two attacks in the 1530s, the settlements of Bahia and São Tomé were destroyed and several others were severely damaged. This was only the beginning of more than twenty years of attacks on settlements, and against the settlers' ready access to firearms the Indians won because of their agility and numbers.[54] However, the Jesuits' comment on "great injustices" against the Indians took on greater meaning in 1559 as the Portuguese, under the leadership of Brazil's third governor general Mem de Sá, began

"… grim, unrelenting, aggressive campaigns that included elements of surprise, night attacks and terror in one blood-drenched encounter after another. Having discovered that the palm-thatched buildings of the Indians burnt readily, the Portuguese systematically torched any village they occupied or passed. The Portuguese recruited and employed Indian allies to devastating effect and incited internecine warfare between politically fragmented Indian groups. This genocidal warfare resulted in the near extinction of many ethnic groups. All this was achieved with relatively few Portuguese troops acting with characteristic daring and brutality."[55]

As this same commentator said, "These battles were a portent of the next three centuries."[56] In response, Indians either fled away from the occupied areas and further into the forests or moved to the aldeias.

In 1749, the Câmara de Belém (Chamber (or Council) of Belém) had informed the king about the “ruin caused to the slave contingent, of which the colonists are so deprived that they see their crops and plantations left to rot” and made two requests: that he authorise the capture of more Indians so they could be entered into labour; and that “as this remedy is still insufficient to replace the many thousands of slaves [who] perished in this plague, we beseech Your Majesty to send some vessels of black slaves [ie African slaves] for them to be shared among the colonists.”[57] Having received no reply, the Câmara wrote again in a 1750 report entitled "Summary of the people who died in the religious service and among the villages they administer and the residents of this city", saying that the number of deaths was "18,377, comprising 7,600 residents of Belém and the remainder from the service and indigenous villages of religious orders."[58]

African slaves were already being imported to Brazil by the mid-16th century and constituted 70% of all immigrants during the first 250 years of colonization. The eventual expansion of export industries including sugar, tobacco and cotton, and later coffee, rubber, gold and diamonds, placed greater demands on the need for a workforce. Although these slaves were more costly than Indians, they were less prone to infectious diseases and could provide labour for longer periods. But because of the hard work and poor diet and living conditions being provided, reports say that disease was rife[59] and early death was common.

Portugal's wealth made of gold

Over time, Portugal's income from Brazil expanded, first from the late 16th century with an increasing production of sugar in the north which gave the empire a virtual monopoly in the market until the mid-17th century when the Dutch set themselves up in opposition.[60] Given the problems of using the Indians as a workforce, the sugar industry became largely dependent on African slaves, making it only one of many other industries which would develop over time. One was the mining industry which at its peak delivered greater wealth to Portugal than sugar.

Exploration for gold, silver and other precious minerals began early in the colony's history when it was carried out in two ways, entradas (literally "entries") which were carried out in the name of and funded by the crown, and bandeiras (flags), the activity of early 17th century Portuguese settlers called Bandeirantes (flag bearers) or Paulistas because of their early concentration in the São Paulo region.[61] Both activities led further and further to the west, ignoring the boundary set up under the Treaty of Tordesillas, to which Spain appeared to turn a blind eye at the time and finally endorsed it when both Spain and Portugal signed the Treaty of Madrid in 1750.

There had been early finds of alluvial gold by the Bandeirantes in the São Paulo region, but the first significant discovery, again theirs, occurred in 1693 the state of Minas Gerais. Later silver, diamonds, emeralds and other valuable minerals were also found in the same area. Exaggerated news of the discovery soon spread and created a major gold rush which attracted vast numbers of people from Portugal in search of their fortunes. Again with the need for a workforce, large numbers of African slaves were brought in to work in the mines, and they were also used later in mining diamonds and other minerals.

Some gold was smuggled illegally over Brazil's borders, some was retained for use in Brazil's local economy (and for decorating its churches), but the bulk was sold by Portugal providing immense wealth which flowed directly into the treasury of the king, João V who was at liberty to spend it as he wished. But rather than using it to build a solid home-based economy, for the aggrandisement of the monarchy and himself he lavished it on building palaces, churches and convents until, by his death in 1750, Brazil's gold output had been reduced to a trickle and the treasury in Lisbon was virtually empty.

After his death, with King José I on the throne, the power of government in Carvalho e Melo's hands, and Portugal's economy desperately in need of revival, increased profit from colonial agriculture, commerce and industry took on high priority.

Treaty of Madrid

As already noted regarding the 1735–37 Spanish-Portuguese War over disputed claims on the Banda Oriental, that had been both preceded and followed by ongoing tension between Spain and Portugal regarding their constant intrusion into each other's territorial boundaries.[62] With Spanish Jesuits already in South America from the 17th century's first decade, and with Spain's king's set on expanding Spain's territory, he gave early instructions for them to set up missions at advanced posts in the upper Amazon. Likewise, under direction from their king, Spain's Carmelites had played a role in extending its influence along the Negro, Madeira and Javary Rivers. Portugal, both officially and unofficially, engaged in similar activities, the westward movement by the Bandeirantes in search for slaves and gold being one example; but the single major force for pushing Brazil's border further to the west on the Amazon came from the Portuguese Jesuits as they set up new aldeias.

The solution for defining Spain's and Portugal's territories was set out in the 1750 Treaty of Madrid where it was stated in Art. I that this new treaty would be "the only foundation and rule that from now on should be followed for the division and limits of the domains throughout the Americas and Asia", making specific reference to those established under Pope Alexander VI's 1493 Bulls of Donation, the treaties of Tordesillas, Lisbon and Utrecht, "and of any other treaties, conventions and promises." So it was stated in that same article:

"[T]hat all this, insofar as it deals with the line of demarcation, will be of no value and effect, as if it had not been determined in everything else in its force and vigor. And in the future it will not be treated more than the aforementioned line, nor can this means be used for the decision of any difficulty that occurs on the limits, but only of the border that is prescribed in the present articles, as an invariable rule and much less subject to controversy."[63]

Although the treaty was an agreement about Portuguese and Spanish territories worldwide, its largest concentration was on defining their borders in the South American continent.[64] Although this task begins in Art. IV, the fact that Art. III focuses specifically on two areas, the Amazon basin and Mato Grosso[65] suggests that there had already been considerable dispute about their territorial ownership; and the Article concludes with the statement: "For this purpose His Catholic Majesty [ie the King of Spain], in his name and his heirs and successors, desists, and formally renounces any right and action, that by virtue of said treaty [Treaty of Tordesillas] or by any other title, may have the aforementioned territories."(Art. III.)

In several articles from Art. IV onwards, rivers, waterways and landmarks are used frequently as demarcations, or where there are no such opportunities, straight lines are run between mountain peaks. The demarcation begins on the coast at the point where the former Banda Oriental del Uruguay borders with Brazil, describing it in the following way:

"The boundaries of the domain of the two Monarchies will begin in the bar that forms, on the coast of the sea, the stream [ie Chuí Stream (Brazilian Portuguese: Arroio Chuí; Rioplatense Spanish: Arroyo Chuy)] that comes out at the foot of the Monte de los Castillos Grandes[66] from whose skirt the frontier will continue, searching in a straight line the highest, or summit of the mountains, whose slopes go down on one side to the coast that runs to the north of the stream, or to the Merin Lagoon, or the Miní, and for the another, to the coast that runs from said stream to the south, or to the Rio de la Plata. By fortune the summits of the mountains shall serve as a line of the domain of the two Crowns. And so the border will be followed, until finding the main origin and head of the Negro River, and above them continue to the main source of the Ibicuí River, following, downstream of this river, to where it flows into the Uruguay River by its eastern bank, leaving to Portugal all the slopes that go down to the said lagoon, or to the Rio Grande de San Pedro; and to Spain, those that go down to the rivers that join together with the one from La Plata." (Art. IV.)

At the end of Art. VII, the treaty reaches consideration of the border along Amazon's main stream which concludes in Art. IX with, "The border will continue through the middle of the Japurá River, and through the other rivers that join it and move closer to the north, until reaching the top of the mountain range[67] between the Orinoco River and the Marañón, or the Amazon;[68][69] and it will continue along the summit of these mountains to the east, as far as the dominion of both monarchies extends."(Arts. IX–XI.)

At various points, the treaty recognises grounds for confusion, including a lack of detailed knowledge of the landscape, and matters which could even become grounds for a dispute in the future. The Amazon basin itself is by far the most problematic area because it had not yet been fully explored by that time. In some cases, the treaty sets forward the way in which such matters should be resolved. For example, regarding islands in rivers which have been used to demarcate borders, Art. X says that "they will belong to the domain to which they were closest in dry weather."

But seeing the need for more clarity, the treaty declares in Art. XII that "both Majesties will appoint, as soon as possible, intelligent commissioners, who, visiting the whole line, adjust with the greatest distinction and clarity, the places where the demarcation has to run, by virtue of what is expressed in this treaty", and that where the commissioners are unable to agree, the matter must be referred back to the monarchs for resolution. The practical arrangement as envisaged by the two kings was that there would be two teams of commissioners, one working from the north[71] and the other from the south.

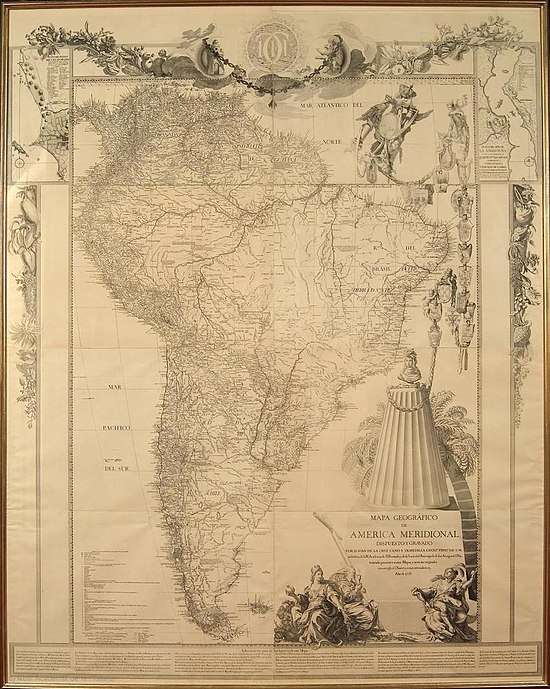

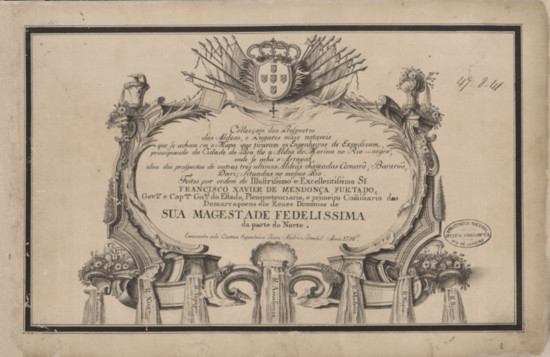

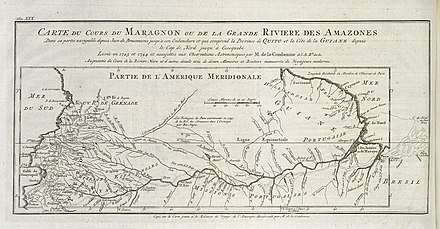

As a way of recording and consolidating these borders, Art. XI directs that as the commissioners demarcate the borders, they will "make the necessary observations to form an individual map of it all; from which copies will be taken that seem necessary, signed by all, and will be kept by the two Courts, in case in the future any dispute is offered on the occasion of any infraction; in which case, and in any other, they will be considered authentic, and they will do full proof. And so that the slightest doubt is not offered, the aforementioned Commissioners will name their common accord to the rivers and mountains that do not have them, and they will indicate it on the map with the possible individuality." The first map to appear after the signing of the treaty was drawn by Spanish cartographer Juan de la Cruz Cano y Olmedilla prior to 1755 (see left).

Major practical outcomes from this treaty are prefaced in Art. XII with the statement, "In view of the common convenience of the two nations, and to avoid all kinds of controversies thereafter, the mutual assignments contained in the following articles have been established and settled." These all relate to the allocation of lands and sometimes the removal of people in areas where major disputes have occurred in the past. These include the Banda Oriental to which the treaty refers as Uruguay, the Colonia del Sacramento, the Japurá River area north of the Amazon, and a Spanish Jesuit area known as Misiones Orientales (Eastern Missions. Also known as: Portuguese: Sete Povos das Missões; Spanish: Siete Pueblos de las Misiones (i.e. Seven Towns of the Missions)).

Already dealt with above, Portugal's foundation of Colonia del Sacramento and the subsequent movement of settlers into the Banda Oriental region had a long, complex history. Art. XIII declares that Colonia del Sacramento, "territory adjacent to it on the northern margin of the Río de la Plata", "the plazas, ports and establishments that are included in the same place" would be allocated to Spain along with navigation along the Río de la Plata. Art. XV then gives instructions about how this will be done, including a requirement that Portugal's military personnel will take no more than their "artillery, gunpowder, ammunition, and boats", giving similar instructions to other settlers who decide to leave regarding what they may remove and granting them permission to sell their property; at the same time, though, anyone who wishes to remain in the area is given permission to do so provided they are prepared to commit their loyalty to the monarch on whose land they live.

.jpg)

The most remarkable, and in the end, the most confrontational, of all provisions emerged in Art. XVI regarding the Misiones Orientales These had been set up in 1609 by the Spanish Jesuits under instruction from Spain's King Philip III to minister to the Guaraní people. The missions were located in an area on the eastern side of Uruguay River immediately north of the Banda Oriental, and shared its eastern border with Brazil. According to the Jesuits' records, there were over 26,000 Guarinís in the seven settlements there and many more in the surrounding areas.[72] Under the treaty, the Spanish king gave the Misiones Orientales area to Portugal and the Jesuits were ordered to move their missions to the western side of the river taking the Indians with them. It took until 1754 for the Jesuits to surrender the territory, but the Guaraní refused to accept Portuguese rule. In response, combined Portuguese and Spanish troops moved in for the beginning of a two-year struggle known as the Guaraní War.[73] It took two years before the Guarinís were defeated and the missions were occupied by the joint forces until 1761 when under the Treaty of El Pardo the Treaty of Madrid was annulled and Spain regained control of Misiones Orientales, retaining it until it was ceded again to Portugal under the 1777 First Treaty of San Ildefonso.

Had the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas (or the Treaty of Madrid and subsequent treaties) been more effective, competition for territorial 'ownership' might have been avoided. And as historian Justin Franco points out, the dispute became immaterial under the Iberian Union between 1580 and 1640, when both countries were being ruled by the same monarchy, the territories of both countries were blurred together and Portuguese colonists were free to move as they pleased. That was one delaying factor, the other being, as he says, how difficult it had been "to delineate vast expanses of unexplored land in the Amazon Rainforest." So it was only at the end of the 17th century, almost 200 years after the signing of the Treaty of Tordesillas, although less than five after the signing of the Treaty of Madrid, that Spain began mapping the continent in detail. It undertook this work with vigour and ensured that the boundaries its territories gained under the Treaty of Madrid were marked. Portugal, by contrast, took no action at this point.[74]

As it happened, though, the demarcation of the entire Spanish-Portuguese border was not completed in the way conceived by the treaty's signatories. The teams working along the southern borders proceeded with minimal delay; but in the north, especially along the Amazon basin's northern tributaries, Spain's team failed to arrive as expected, and the Jesuits' opposition further frustrated Mendonça Furtado's work on Portugal's behalf. Nor was the treaty itself well-observed because both Spanish and Portuguese settlers took the opportunity to move about freely wherever no armed forces were available to guard the boundaries. In the end, the process of demarcation was victim to the succession of treaties as described above.

Mendonça Furtado as governor

Carvalho e Melo's reforms and Mendonça Furtado's appointment

João V's son and successor, José I, with no interest in the day-to-day responsibilities of government, delegated authority to Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo as Secretary of State of Internal Affairs (Portuguese: Ministério da Administração Interna). Carvalho e Melo, at the same time highly authoritarian and dictatorial but also a vigorous reformist[76], had among his many goals the rebuilding of the country's economy so it could recover from its own demise in the hands of the former king.

His approach was highly centralist; he saw himself at the helm of the entire structure and he always wanted to know what was going on. This was not only in regard to Portugal's internal operation but the colonies as well, and this quickly flowed into a reshaping of the governmental and administrative structure in Brazil from which he required regular reporting to himself and unquestioning obedience to any directives issued by him.[77][78] Among Carvalho e Melo's broad range of reforms, possibly the most significant for the operation of the empire's economy was the creation of the Royal Treasury (Portuguese: Erário Régio] in 1761. In concept it involved the abolition of the old model in which the treasury's operation was under the direct and absolute absolute control of the monarch (as it had been, for example, under King João V). This new treasury was under Carvalho e Melo's direct control, it had seniority over all other executive and administrative bodies except, theoretically, the king himself, and it processed and administered all income and expenditure related to those bodies in both Portugal and rest of the empire.[79]

In view of the failures of the old system of captaincies (See Early Colonial Structures above) Carvalho e Melo acted quickly by reconstructing the colony into two states. This took place on 31 July 1751 when he retained in the south the State of Brazil (Portuguese: Estado do Brasil) which had already existed since 1621, and established in the north a new State of Grão-Pará and Maranhão (Portuguese: Estado do Grão-Pará e Maranhão) to which he had already appointed his brother Mendonça Furtado as its governor (Portuguese: governador) and captain-general (Portuguese: capitão-general).[80][81]

The new northern state was a replacement of its predecessor the State of Maranhão which had contained three crown captaincies, Pará, Maranhão and Piauí, and six small donatory-type captaincies, Cabo do Norte, Marajó, Xingú, Caeté, Cametá and Cumá, all on the peripheries of the Amazon's delta. The small captaincies had been largely unproductive, but Pará was seen by the government as being economically productive and, in view of its location, of great strategic importance to the basin. Between 1751 and 1754, all these smaller captaincies were subsumed by the crown.[82]

With the creation of the new state, the capital was moved from São Luís located on the Atlantic shoreline to Belém do Pará, sometimes referred to as Nossa Senhora de Belém do Grão Pará (Our Lady of Bethlehem of Grao-Para) and Santa Maria de Belém (St. Mary of Bethlehem), on the Amazon River's south shore near its mouth. The new location was based on Carvalho e Melo's request that Portugal develop a stronger presence at this point and westwards along the river.

%2C_State_of_Gram_Par%C3%A1_State_(1756).png)

At the outset Mendonça Furtado received a set of 38 directives usually referred to as the "Royal Instructions" (Portuguese: Instruções Régias)[84][85] or "Secret Instructions"[86] dated 31 July 1751, which a commentator has described as "a Portuguese Project for the Amazon."[87] Although issued under the king's name and penned by his Secretary of State for Overseas Affairs, Diogo de Mendonça Côrte Real, given the king's distance from the functions of government, and taking into account the close relationship these instructions have with Carvalho e Melo's own objectives, it seems more than likely that he was either the author or directly involved in drafting the document.[88]

The "fundamental objective" of the Instruções Régias has been described as "incorporating a territory usually forgotten and little explored by the Portuguese crown, in the Portuguese-Brazilian mercantile system."[89] According to one historian, these instructions are focussed largely on three topics: (1) "the status of the Amazon's Indian population"; (2) "the Jesuits and other religious orders … especially with regard to potential reforms to their relationship with the Indians"; and (3) "further surveying the nature and extent of the region’s commercial potential, including the expansion of trade and the potential for establishing plantations." "The overall impression left by the Instructions, especially in the convergence of the three categories just mentioned, is of a mandate for Mendonça Furtado to ensure that the state of Grão Pará and Maranhão and its inhabitants – both the Portuguese settlers and the Indians – more effectively and efficiently provided both economic and political support to the Portuguese Crown."[90]

Another historian suggests, "The creation of this new administrative unit [ie the state of Grão-Pará and Maranhão] demonstrates the centrality that the frontier region acquired with the continuity of the policy of expansion of the Portuguese Empire further west of the Amazon River, through the infiltration of the rivers Negro, Branco, Madeira, Tapajós, Xingu and Tocantins", and continues, "The occupation of the territories nearer and nearer to the Spanish borderlands acquired a fundamental importance for the Portuguese Empire in the last three decades of the seventeenth century, aimed at the strengthening of monarchical sovereignty over these vast territories, as well as the opening of new commercial channels that could generate more wealth."[91] It could be, then, that the expansion and consolidation of the Portuguese territory in the face of competition from Spain was the overarching motive behind the creation of the two states.[92] This would have to be achieved to ensure that Portugal's income could be guaranteed, and it is clear from the Instruções Régias that Carvalho e Melo saw it this way.

Regarding the Indians, according to several of the Instruções Régias, Mendonça Furtado was to end their subjection to slavery and to arrange instead for them to be employed, but only on condition that they be paid wages for their work. As much as it sounds like "freedom" for the Indians, in reality it was only a transfer of the Indians from one form of labour to another because the obligation remained for them to be engaged in productive work, and the idea of their returning to their original tribal lifestyle was out of the question.[93]

At this early stage, the idea of expelling the Jesuits from Brazil was not yet fully on the agenda. However, they were not off the hook because in the instructions Mendonça Furtado was directed to investigate the Jesuits' wealth and landholding "with great caution, circumspection, and prudence".[94]

His attitude towards the Jesuits could already have been set in place under his brother's influence because, although the Jesuits' pre-eminence in Portugal had been achieved through their participation in and control of education and the close relationship they had already developed as confessors and advisors with the crown, court and aristocracy in earlier generations and right up to the reign of King João V, Carvalho e Melo's opposition to them had already been formed during his days in Vienna and London, and it seems possible that their eventual expulsion from Portugal and Brazil was a direct outcome of his earlier experiences.

But it is a matter of ongoing debate in modern historical interpretation regarding the extent to which negative views towards the Jesuits in Portugal were based on truth or myth. One historian says:

"In Portugal, the great architect of the anti-Jesuit myth was the Marquis of Pombal. It corresponded to a centralization process of the absolutist state, keeping the control of education, which belonged to the Society of Jesus...This myth had such a lasting negative impact in the Portuguese society that even today they are seen by many as responsible for obscurantism and as enemies of science."[95]

Evidence from the 19th century illustrates how Pombal's attitudes towards the Jesuits had entered the public mind and continued to emerge in other contexts. For example, a quote from 1881 says:

"[T]hey accuse the Jesuits of committing all kinds of crimes, from larceny to murder, of plotting in the darkness against freedom, of turning credulous spirits into fanatics, terrorizing them with the ridiculous paintings of Hell and of the dreadful punishments of eternity; of teaching the beliefs, thus preparing the youthful spirits for their future work of destruction; of abusing the trust that in the naive their hypocritical humbleness inspires, to, one day, raise the strength, light up the fire and douse in blood the martyrs of this land of liberals." [96]

The irony is that Pombal was a graduate of the Jesuit-run University of Coimbra (Portuguese: Universidade de Coimbra), one of the largest and wealthiest of all Portuguese education institutions, and the author's just quoted have suggested that the Jesuits were actually playing a leading role throughout Portugal in the advancement of scientific knowledge and research, the development, innovation and dissemination of pedagogic practice, and the expansion of teaching facilities including free schools for the poor.[97]

Mendonça Furtado takes office

When Mendonça Furtado arrived in Belém do Pará in October 1751, it was the largest settlement in the Amazon region, and its only shipping port, although as Alden says, impaired by the fact that in the early 18th century the movement of shipping between it and the Iberian peninsula was rare and irregular compared with other major shipping centres such as Recife, Salvador and Rio de Janeiro.[98]

The problem was that, with the colony largely concentrated on the coast, the state's overall population was low. Along the Amazon and its tributaries few settlers had moved westward into the more remote areas, there was only a tiny number of smaller towns and villages, the Indian population was small and few African slaves had been added to the workforce.

There were Catholic missions run by Franciscans, Carmelites and Mercedarians. But the dominant factor was the huge network of Jesuit missions with their aldeias. As owner of the largest properties in the region, and by using the Indian workforce, the Jesuits were dominant operators in the areas of ranching, agriculture, silviculture and fishing. Because of the epidemics of smallpox, measles, and other infectious diseases, few households had slaves, former Indian villages were unoccupied and the workforce was small.

Clearly Mendonça Furtado was facing no easy task, for four main reasons: Jesuits were 'suspected' of exploiting the Indians and treating them harshly if they refused to work as instructed; the Jesuits' opposition to any intrusion in their affairs, including their control over large number of Indians, was predictable; the settlers had a long history of abusive, exploitative and low cost dependence on Indian slaves which had continued long after African slaves started arriving because the imported slaves were a great deal more expensive; and the concept of enforced labour was deeply embedded in Brazil's economic and social structure.

Knowing how the Jesuits would respond, the instructions directed Mendonça Furtado to seek assistance from a strong supporter of the monarchy, the Bishop of Belém do Pará, Miguel de Bulhões e Souza [or Sousa] in setting the new laws governing Indian employment in place especially by instructing the Jesuits to concentrate their work on religious instruction. But the idea of restricting the Jesuits' activities was not stimulated by a desire to "punish" them: Carvalho e Mello's clear motivation was economical, because by placing a stranglehold on their involvement in production, more opportunities would be created for others to invest in agricultural and commercial projects, and the state of Grão-Pará and Maranhão's contribution to Portugal's economy would be able to increase.

In the same way, the settlers' response was foreseen in the instructions, and Mendonça Furtado was directed to ensure that they "observe this Resolution completely and religiously” by persuading them to see the benefits of using African slaves,[99] a difficult task because the cost of setting up and running plantations and other large enterprises in the Amazon was higher than in other parts of Brazil; and given the Jesuits' near monopoly on Indian labour and their ability to outbid others in buying African slaves, the Amazon's business developers had struggled to survive.

As Mendonça Furtado later reported, he issued "positive orders for the civilization of the Indians, to enable them to acquire a knowledge of the value of money, something which they had never seen, in the interests of commerce and farming, and … familiarity with Europeans, not only by learning the Portuguese language, but by encouraging marriage between Indians and Portuguese, which were all the most important means to those important ends and together to make for the common interest and the well-being of the state."[100] Furthermore, having defined the vital strands of output as sugar, tobacco and gold, measures were set in place to protect and support these producers. A price control system was placed over all staple items so colonists could survive on their existing incomes, and an inspection system was set up to monitor it.

Within a year of taking office, fully aware of the clandestine warehousing, illegal exporting and smuggling, along with systems that had enabled traders to bypass the crown's taxes on exports, he had channelled all exporting through state-managed outlets with the movement of goods carefully recorded. That all sounded good in theory; in reality, controlling the movement of goods out of Brazil was next to impossible because there were too many ways of doing so, and few people to monitor where, when and how it was being done.

As for the plan to liberate and Europeanise the Indians, especially those under the control of the Jesuits within the aldeias, married to the idea that they would then be induced to populate regions closer to the borders, this, too, led nowhere.

Defence and fortification in the Amazon Basin

The task of developing the state's potential as a source of income was clearly part of Carvalho e Melo's agenda, yet in the Instruções Régias priority was given to security and fortification, and it was only well into the document where colonial development and income was finally discussed:

"I urge you to look carefully at the means of securing the State, as well as to make commerce flourish, in order to achieve the first aim … and you will be careful, as far as possible, to populate all possible lands, introducing new settlers." (Instruções Régias, Inst. 27.)

Discussion about security occurred in the other instructions: for example, regarding the requirements for armed forces the document says, "I instruct you to inform me of the number of troops that may be necessary for the service of the State" (Instruções Régias, Inst. 24), and in another Mendonça Furtado was told to review, strengthen and fortify his region, building new defences where needed (and to direct the Governor of Maranhão to do the same). (Instruções Régias, Inst. 28.)

Records show that in 1751 there were only about 300 men allocated to Belém and the forts of Macapá, Guamá, Gurupá, Tapajós, Pauxis and the Rio Negro, and that the forces in Maranhão were also low. Evidence also shows that the provision of arms and ammunitions was also insufficient.[101] Mendonça Furtado's own assessment saw the situation in the same way and he quickly conveyed the message back to Lisbon.

Action followed to strengthen the defence system by increasing the volume of men and equipment and expanding the fortifications. A massive enlistment program was carried out in Portugal and in April 1753 900 men were shipped to Brazil to form two regiments, one to be based in Belém and, in principle, the other at Macapá. With them came 42 families made up of 109 women and children, indicating a significant sudden population increase in just these two centres. In the same fleet that transported these people, other ships carried arms, military equipment and uniforms in quantities suitable for the travelling regiments and for those soldiers already on the ground in the northern state. These and other ships also carried as ballast large stones for the building of fortification. Many of these were used in the coastal areas while others were transported in canoes up the rivers for use in new forts.[102]

The use of Macapá for defence purposes was strategic because of its location on the Atlantic coast and on the Amazon's northern estuary at the junction between the river's mouth and the ocean. A military detachment had been located in a small fortified structure there since 1738. But this was clearly inadequate as far as the Portuguese government was concerned, and the message was well-conveyed to Mendonça Furtado. By December 1751, within three months of his arrival, he travelled to the site, immediately initiating plans for the building of a larger fort. He also arranged for settlers to be brought in from the Azores so there was a reasonably-sized civil population to support the expected increase in armed services. By 1752 he had heard that enlistment was being carried out in Portugal and news that a cholera epidemic had affected the population there made him return to assess the situation. As already mentioned, in 1753 the two regiments arrived from Lisbon, and although one was meant to go to Macapá, Mendonça Furtado had said this could only happen if the fort had been completed. He continued to apply pressure, especially in 1754 when the French invaded north of the Oyapock River ( Portuguese: Rio Oiapoque) into what became French Guiana.

The fact that the fort, now known as the Fortaleza de São José de Macapá was not completed until 1771, 20 years after Mendonça Furtado set the plan in motion, raises questions when considered against that conclusion of that same instruction which reads:

"I warn you that both this fortress and all the others that are made for the defence and security of this state, must be done in a manner that does not appear to be a fear of our restrictions, while at the same time caution must be maintained so we are not surprised by the renewal of false claims, making it impossible because we have to dispute them all forcefully." (Instruções Régias, Inst. 28.)

Another site of importance to Lisbon was the Rio Branco about which they learnt in 1750 reports that the Dutch had entered the area from Suriname via the Essequibo River (Portuguese: Rio Eseqüebe) so they could trade with the Indians and take them into slavery. The king and his Overseas Council responded at the end of 1752 by ordering Mendonça Furtado "that without any delay a fortress should be erected on the banks of the said Rio Branco, at the place which you consider to be most proper, first having consulted with the engineers whom you appoint for this examination, and that this fortress is always staffed with a company of the Macapá regiment, which changes annually."[103][104]

Warnings continued to come for about 20 years, one reporting that the Paraviana Indians had gained possession of weapons, gunpowder and shot. But no action was taken to erect the fort until a report arrived in 1775 that Dutch settlers had been living on Portuguese territory for four years. The Lisbon government responded by ordering the erection of what became known as the Forte de São Joaquim do Rio Branco (Fort of São Joaquim do Rio Branco) and work started in that same year, more than twenty years after the king's original order was issued.[105] The government clearly wanted Mendonça Furtado to get things done quickly, and some signs indicated that he took that seriously, and yet lethargy or inaction somewhere - and was it Lisbon's? - somehow got in the road.[106][107]

Preparation for the journey on the Amazon

In 1752 Mendonça Furtado was appointed both as plenipotentiary for Portugal's crown, and under the Treaty of Madrid arrangements as its commissioner for the northern region.[108][109]

In that same year Spain appointed José de Iturriaga as its First Commissioner making specific mention of the rivers of Javari, Japurá, Negro and Madeira for his attention, while at the same time he was also appointed as commander (Spanish: comandante general) of new settlers on the Orinoco River and given other tasks including leading a major scientific research program on that river.

Fritz_Samuel_btv1b8446616z.jpg)

As it turned out, and probably unbeknown to both the Portuguese government and Mendonça Furtado, Iturriaga did not leave Spain until 1754 and rather than travelling directly to meet with Mendonça Furtado, he went to Venezuela and accompanied the scientists on their program while at the same time working with the other Spanish commissioners the so-called Expedition of Limits to the Orinoco (Spanish: Expedición de Límites al Orinoco) which involved demarcating the borders along the Orinoco.[110][111]

Prior to Mendonça Furtado's time in office, large parts of the northern Amazon basin had not yet been fully explored, although Spain's mappers had been active since 1637. The first accurate and complete map of the Amazon and Orinoco Rivers had been published in 1707 after being charted by Czech Jesuit Samuel Fritz who had journeyed by river from Quito in Ecuador to Pará. However, even the most detailed maps at that time were not sufficient to help him meet the obligations he had been given in the Instruções Régias.

Rather than wait for news from Spain about their commissioners' movements, he decided to make an independent journey upstream on the Amazon. To help plan the details, he consulted with people such as the Bishop of Belém do Pará, members of the Câmara de Belém and those settlers who had shown interest in cooperating with the government.

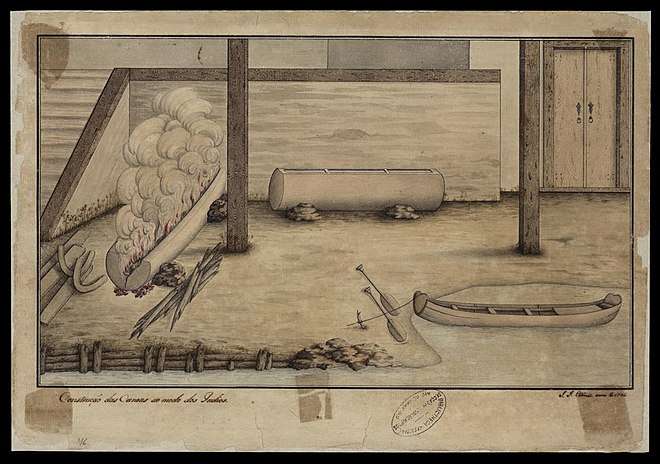

Frustrations soon arose, though. The canoes required to transport himself and the working party he had originally intended to buy ready-made either from Indians in the aldeias and from settlers. The Jesuits were obstructive to this and he was only able to obtain a small number.

His next proposal, contained in correspondence he sent to Lisbon, was that the canoes be made on his royal estate where timber was freely available. For that he required funds to cover the costs including additional labour. However, with correspondence flowing slowly backwards and forwards across the Atlantic, he found himself waiting for an answer.

Finally, rather than delay any longer, without Lisbon's approval he decided to employ Indians who had been given permission to work for him. Further complications were caused, though, as Indians abandoned their work without warning, even using canoes they had already made to return to their aldeias. This meant his plan to set off in May 1754 was delayed until October of that year.

Start of the journey

The departure from Belém was carried out in grand, viceregal style.

"On 2 October 1754, His Excellency left his palace accompanied by all the different people, and went to the church of Our Lady of Mercy where he heard Mass and received communion, and after having made this pious and Catholic step embarked with the Most Excellent and Reverend Lord Bishop [D. Miguel de Bulhões] in his large canoe, with the general feeling and greeting of all those who accompanied him to the beach, and with him all the expedition people embarked in their canoes and then set off, enlisted infantry, who had formed on the beach, providing three discharges of musketry, followed by the salvos of all the artillery of the forts."[112]

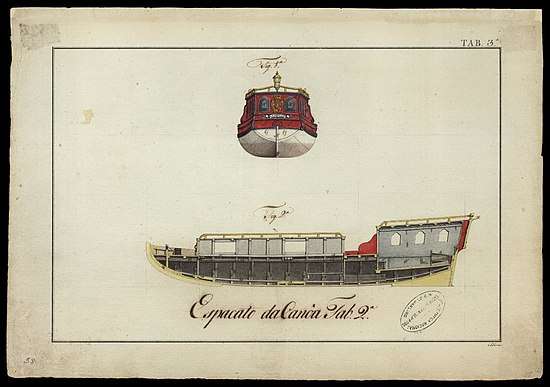

In its entirety the flotilla was made up of 28 canoes, fitted with sails for use when wind was available, and all painted in the vice-regal colours of red and blue. Five carried storage and infantry, five were fishing canoes to help provide food during the journey, eleven transported geographers, astronomers,[113] engineers, cartographers, artists and other officials who were to assist the governor with mapping and demarcation. Vice-regal staff in attendance included the Secretary of State, the Chamber Adjutant and the Purveyor of the Royal Estate.[114][115] Also, to provide necessary food resources on the way, especially flour, he wrote in advance to clergy in the largest aldeias asking them to hold these supplies for collection on his party's arrival.

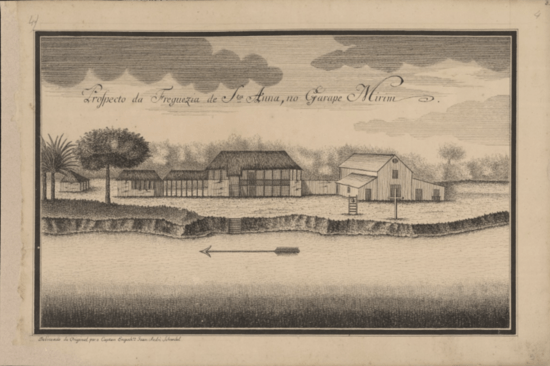

The two largest vessels had clearly been designed under Mendonça Furtado's direction so they represented his status as governor and provided him with comfort. His own canoe, the larger of the two and about the size of a yacht and probably very similar to that illustrated here (left), included:

"…a rather roomy chamber, all lined with crimson damask with golden decoration; this chamber was built in with coffer chests covered with cushions of the same crimson, and in addition to these, it had six more footstools and two upholstered chairs with a large table and a cabinet of yellow wood with the portrait of the king in the top. There were four windows on each side, and two on the top panel, all of which were trimmed with finely crafted carving, and the royal arms in the middle, all very well gilded, and the rest of the canoe painted red and blue."[116]

Both vessels had rowing crews, 26 for the governor's and 16 for the other, dressed in a uniform of white shirts, blue pants and blue velvet caps.

At the outset the entire party numbered 1,025 people, including 511 Indians 165 of whom deserted during the journey. Bishop Bulhões travelled with the governor for the first week before returning to Belém where he acted as executive and provided a channel for correspondence between the governor and Lisbon.

Stages of the journey

The journey itself took three months and on the way, Mendonça Furtado visited a number of aldeias, enghenos (sugar mills) and plantations, observing and assessing at first hand the Indians' living and working conditions, their relationship with the Jesuits, the Jesuits' attitude towards himself, and the Amazon basin's overall potential for future use. The whole journey was noted in log book style by the Secretary of State João Antônio Pinto da Silva.[117]

The first visit was to the royal estate on the Rio Moju where timber was produced and canoes were made. The party stayed there to allow time for new canoes to be sent to Belém and the first visit to a sugar mill took place. The journey then continued to Igarapé-Miri (or Mirim) on the river of the same name. This was the fifth day of the journey, and once there Bishop Bulhões celebrated Mass in the parish church and then departed to return to Belém.

Mendonça Furtado's first negative interaction with the Jesuits on this journey occurred on day eleven at the aldeia of Guaricurú, by report one of the largest. On arrival they found it deserted except for a priest, three old Indians, some boys and a few Indian women who were related to the Indians on the governor's crew.

The diary includes a parenthesized note saying, "the first manifestation of resistance or hostility by the priests of the Society of Jesus against the fulfilment of the Preliminary Limitations Treaty, signed in Madrid on 13 January 1750."[118] Although this is in the writer's hand, it might well represent an opinion expressed by the governor himself.

Guaricurú was one place in which the governor had requested flour to be kept for his collection. However, those in the aldeia seemed to know nothing about this, and after a search was made the flour was located in the priests' house. With labour required to load the flour onto the canoes and with repairing faulty canoe ropes, the next day the governor sent soldiers into the surrounding area to search for the Indians. But only a few appeared and "confessed that everyone had fled because of the practice and instruction the priest had given them."[119] Mendonça Furtado later reported this along with insolent behaviour by the priest and other observations in a letter to Bishop Bulhões.[120]

From there the party proceeded to the next aldeia at Arucará (later renamed by Mendonça Furtado as Portel) which was abandoned except for the Indian chief and a few of his people. Because he wanted to add extra Indians to his crew in case more deserted already deserted, Mendonça Furtado noted the chief's unwillingness either to help or obey his orders.

.png)

Four days on from Arucará the party arrived at the fort of Gurupá where the governor was greeted with a military salute. They remained there for three days so they could rest and rebuild supplies, and Mendonça Furtado entertained the officers and all his entourage except the Indians at the table. Noting the poor state of the church when Mass was celebrated there, the governor gave a large sum of money for use in its renovation.[121] He also had money distributed among the soldiers. Flour and dried fish was collected for later use. On return to the canoes to set sail it was discovered that 16 more Indians had deserted. This meant that by their next stop, the total was 36 and voyage diartist Silva noted that the majority had come onto the voyage from aldeias which he took as confirming his opinion about the role the Jesuits had played in turning their minds against the governor.

Several more days included visits to aldeias being run by the Capuchins where their welcome contrasted strongly with the response they had received in Jesuit settlements, and likewise, flour and other supplies were also readily available. As an example of Capuchin hospitality, at Arapijó the governor was welcomed to the table and his entourage was offered gifts of bananas by the Indians. In return he gave then ribbons, knives, cloth and salt. Silva noted this aldeia as being very poor and swarmed with mosquitoes (Brazilian Portuguese derived from Tupi: carapanã, denoting a mosquito which is now recognised as a transmitter of dengue fever and malaria) "so that at night we were very mortified."[122]

The remainder of the trip to Mariuá included visits to aldeias, enghenos and plantations, with nothing new to reveal except that Indian desertion continued so that by the time of the journey's conclusion 165 Indians had deserted during the journey. This constant recurrence of Indian desertion and his difficulty finding others to replace them preoccupied Mendonça Furtado's correspondence with Bishop Bulhões and others.

Apart from the delays this was causing in his journey, he also dwelt on how, without the guaranteed involvement of Indians he was going to be able to care adequately for his household and guests, including the Spanish commissioners he was expecting to see once the journey was completed.

This ongoing experience had reshaped his attitude towards the Indians in whom he had wrongly assumed he would see a willingness to work, but had actually observed the opposite. As a reading of his correspondence suggests, although his criticism of the Indians increased, from a European perspective, he seemed unable to comprehend how they were part of a historical-ethnic-societal structure in which habits, values and beliefs were very different from those held in societies from which he and other colonists had emerged.[123] In any case, he continued to project the blame for their behaviour onto the Jesuits who he judged as having failed to develop civilized behaviour among the Indians, and equally seriously, had turned them against loyalty to the Portuguese empire and its crown.

Stay in Mariuá

%2C_Brazil.jpg)

In December 1754 the journey ended at Mariuá (now known as Barcelos) on the Rio Negro a distance upstream from its mouth with the Amazon. Colonial use of the site had already begun in 1729 when the Carmelites set up the aldeia of Mariuá (also known as the Missão de Nossa Senhora da Conceição de Mariuá) as a mission to the Manaus, Baré, Pariana, Uiraquena and Passé Indians.

By the time of Mendonça Furtado's journey, it had been designated as the place where he and Spain's plenipotentiary, José Iturriaga would meet so they could begin their demarcation of the northern borders. To ensure that conditions were suitable for himself and his party he had already sent ahead military officer Gabriel de Sousa Filgueiras[124] whose praise he declared when writing to his brother because on arrival he found barracks erected and plantations of manioc (cassava) and maize well advanced.[125]