Religious habit

A religious habit is a distinctive set of religious clothing worn by members of a religious order. Traditionally some plain garb recognizable as a religious habit has also been worn by those leading the religious eremitic and anchoritic life, although in their case without conformity to a particular uniform style.

In the typical Roman Catholic or Anglican orders, the habit consists of a tunic covered by a scapular and cowl, with a hood for monks or friars and a veil for nuns; in other orders it may be a distinctive form of cassock for men, or a distinctive habit and veil for women. Modern habits are sometimes eschewed in favor of a simple business suit. Catholic Canon Law requires only that it be in some way identifiable so that the person may serve as a witness of Gospel values. This requires flexibility and creativity. For instance in Turkey, a Franciscan might wear street clothes.

In many orders, the conclusion of postulancy and the beginning of the novitiate is marked by a ceremony, during which the new novice is accepted then clothed in the community's habit by the superior. In some cases the novice's habit will be somewhat different from the customary habit: for instance, in certain orders of women that use the veil, it is common for novices to wear a white veil while professed members wear black, or if the order generally wears white, the novice wears a grey veil. Among some Franciscan communities of men, novices wear a sort of overshirt over their tunic; Carthusian novices wear a black cloak over their white habit.

In some orders, different types or levels of profession are indicated by differences in habits.

Buddhism

Kāṣāya (Sanskrit: काषाय kāṣāya; Pali: kasāva; Chinese: 袈裟; pinyin: jiāshā; Cantonese Jyutping: gaa1saa1; Japanese: 袈裟 kesa; Korean: 袈裟 가사 gasa; Vietnamese: cà-sa), "chougu" (Tibetan) are the robes of Buddhist monks and nuns, named after a brown or saffron dye. In Sanskrit and Pali, these robes are also given the more general term cīvara, which references the robes without regard to color.

Origin and construction

.jpeg)

Buddhist kāṣāya are said to have originated in India as set of robes for the devotees of Gautama Buddha. A notable variant has a pattern reminiscent of an Asian rice field. Original kāṣāya were constructed of discarded fabric. These were stitched together to form three rectangular pieces of cloth, which were then fitted over the body in a specific manner. The three main pieces of cloth are the antarvāsa, the uttarāsaṅga, and the saṃghāti.[1] Together they form the "triple robe," or tricīvara. The tricīvara is described more fully in the Theravāda Vinaya (Vin 1:94 289).

Uttarāsaṅga

A robe covering the upper body. It is worn over the undergarment, or antarvāsa. In representations of the Buddha, the uttarāsaṅga rarely appears as the uppermost garment, since it is often covered by the outer robe, or saṃghāti.

Saṃghāti

The saṃghāti is an outer robe used for various occasions. It comes over the upper robe (uttarāsaṅga), and the undergarment (antarvāsa). In representations of the Buddha, the saṃghāti is usually the most visible garment, with the undergarment or uttarāsaṅga protruding at the bottom. It is quite similar in shape to the Greek himation, and its shape and folds have been treated in Greek style in the Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhāra.

Additions

Other items that may have been worn with the triple robe were:

- a waist cloth, the kushalaka

- a buckled belt, the samakaksika

Kāṣāya in Indian Buddhism

In India, variations of the kāṣāya robe distinguished different types of monastics. These represented the different schools that they belonged to, and their robes ranged widely from red and ochre, to blue and black.[2]

Between 148 and 170 CE, the Parthian monk An Shigao came to China and translated a work which describes the color of monastic robes utilized in five major Indian Buddhist sects, called Dà Bǐqiū Sānqiān Wēiyí (Ch. 大比丘三千威儀).[3] Another text translated at a later date, the Śariputraparipṛcchā, contains a very similar passage corroborating this information, but the colors for the Sarvāstivāda and Dharmaguptaka sects are reversed.[4][5]

| Nikāya | Dà Bǐqiū Sānqiān Wēiyí | Śariputraparipṛcchā |

|---|---|---|

| Sarvāstivāda | Deep Red | Black |

| Dharmaguptaka | Black | Deep Red |

| Mahāsāṃghika | Yellow | Yellow |

| Mahīśāsaka | Blue | Blue |

| Kaśyapīya | Magnolia | Magnolia |

In traditions of Tibetan Buddhism, which follow the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya, red robes are regarded as characteristic of the Mūlasarvāstivādins.[6]

According to Dudjom Rinpoche from the tradition of Tibetan Buddhism, the robes of fully ordained Mahāsāṃghika monastics were to be sewn out of more than seven sections, but no more than twenty-three sections.[7] The symbols sewn on the robes were the endless knot (Skt. śrīvatsa) and the conch shell (Skt. śaṅkha), two of the Eight Auspicious Signs in Buddhism.[8]

Jiāshā in Chinese Buddhism

In Chinese Buddhism, the kāṣāya is called gāsā (Ch. 袈裟). During the early period of Chinese Buddhism, the most common color was red. Later, the color of the robes came to serve as a way to distinguish monastics, just as they did in India. However, the colors of a Chinese Buddhist monastic's robes often corresponded to their geographical region rather than to any specific schools.[9] By the maturation of Chinese Buddhism, only the Dharmaguptaka ordination lineage was still in use, and therefore the color of robes served no useful purpose as a designation for sects, the way that it had in India.

Eastern Orthodoxy

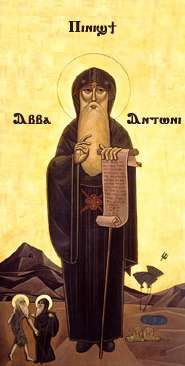

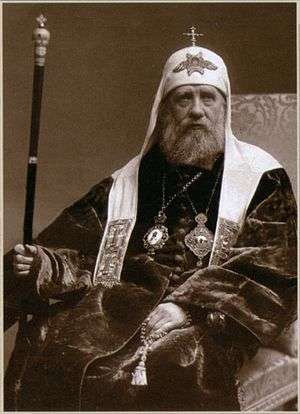

The Eastern Orthodox Church does not have distinct religious orders such as those in the Catholic Church. The habit (Greek: Σχήμα, Schēma) is essentially the same throughout the world. The normal monastic color is black, symbolic of repentance and simplicity. The habits of monks and nuns are identical; additionally, nuns wear a scarf, called an apostolnik. The habit is bestowed in degrees, as the monk or nun advances in the spiritual life. There are three degrees: (1) the beginner, known as the Rassaphore ("robe bearer") (2) the intermediate, known as the Stavrophore ("cross bearer"), and (3) the Great Schema worn by Great Schema Monks or Nuns. Only the last, the Schemamonk or Schemanun, the monastic of the highest degree, wears the full habit.

The habit is formally bestowed upon monks and nuns at the ceremony known as the tonsure. The parts of the Eastern Orthodox habit are:

- Inner Rason (Greek: Έσώρασον, Ζωστικὸν or Ἀντερί, Esórason; Slavonic: Podryásnik): The inner rason (cassock) is the innermost garment. It is a long, collared garment coming to the feet, with narrow, tapered sleeves. Unlike the Roman cassock, it is double-breasted. The inner rason is the basic garment and is worn at all times, even when working. It is often given to novices and seminarians, though this differs from community to community. The inner rason is also worn by chanters, readers, and the married clergy. For monks and nuns, it symbolizes the vow of poverty.

- Belt (Greek: Ζώνη, Zone; Slavonic: Poyas): The belt worn by Orthodox monks and nuns is normally leather, though sometimes it is of cloth. In the Russian tradition, married clergy, as well as the higher monastic clergy, may wear a cloth belt that is finely embroidered, especially on feast days. The belt is symbolic of the vow of chastity.

- Paramand (Greek: Παραμανδύας, Paramandýas; Slavonic: Paraman): The Paramand is a piece of cloth, approximately 5 inches square which is attached by ribbons to a wooden cross. The cloth is embroidered with a cross and the Instruments of the Passion. The wooden cross is worn over the chest, then the ribbons pass over and under the arms, like a yoke, and hold the square cloth centered on the back. The paramand is symbolic of the yoke of Christ (Matthew 11:29–30).

- Outer Rason (a.k.a. riasa, Greek: εξώρασον, exorason or simply ράσο, raso; Slavonic: ryasa): Among the Greeks it is worn by readers and all higher clerics; among the Russians it is worn only by monks, deacons, priests, and bishops.

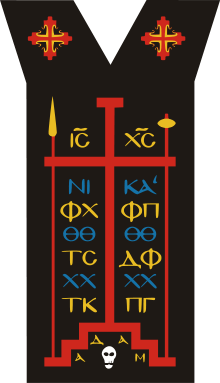

- Analavos (Greek: Άνάλαβος; Slavonic: Analav): The distinctive dress of the Great Schema is the analavos, and it is worn only by Schemamonks and Schemanuns. Traditionally made of either leather or wool, the analavos covers the shoulders, and then comes down in the front and back, forming a cross (see illustration, above right).

- Polystavrion (Greek: Πολυσταύριον, lit. "many crosses"): The polystavrion is a long cord that has been plaited with numerous crosses forming a yoke that is worn over the analavos to hold it in place.

- Mantle (Greek: Μανδύας, Mandías; Slavonic: Mantíya): The Mantle is a long, full cape, joined at the neck which the monastic wears over the other parts of the habit.

- Kalymafki (a.k.a. Kalimavkion, Greek: καλυμαύκι; Slavonic: klobuk): The distinctive headdress of Eastern Orthodox monks and nuns is the kalymafki, a stiffened hat, something like a fez, only black and with straight sides, covered with a veil. The veil has lappets which hang down on each side of the head and a stylized hood falling down the back. For monastics of the Great Schema, the kalymafki takes a very distinctive shape, known as a koukoulion (cowl), and is embroidered with the Instruments of the Passion. The koukoulion is also worn by the Patriarchs of several local churches, regardless of whether or not he has been tonsured to that degree. In the Slavic tradition, the koukoulion will be in the form of a cloth hood, similar to that worn on the Western cowl. Outside church, monastics wear a soft hat known as a Skufia. Again, for Schemamonks and Schemanuns it is embroidered with the Instruments of the Passion.

The portions of the habit worn by the various degrees of monastics is as follows:

| Rasophore | Stavrophore | Great Schema |

|---|---|---|

| Inner Rason | Inner Rason | Inner Rason |

| Belt | Belt | Belt |

| Paramand | Paramand | |

| Outer Rason | Outer Rason | Outer Rason |

| Analavos | ||

| Mantle (Russian use only) | Mantle | |

| Polystavrion | ||

| Kalymafki | Kalymafki | Koukoulion |

Gallery

Inner Rason worn by Polish Orthodox Church cleric

Inner Rason worn by Polish Orthodox Church cleric.jpg)

_at_the_Mount_Athos%2C_1850s.jpg) Monk at the Mount Athos, 1850s

Monk at the Mount Athos, 1850s

Hinduism

Islam

Jainism

Female ascetics and Svetambara male monks always wear un-stitched or minimally stitched white clothes. Digambara Jain monks do not wear clothes. A loin cloth which reaches up to the shins is called a Cholapattak. Another cloth to cover the upper part of the body is called Pangarani (Uttariya Vastra). A cloth that passes over the left shoulder and covers the body up to a little above the ankle is called a Kïmli. Kïmli is a woolen shawl. They also carry a woolen bed sheet and a woolen mat to sit on. Those who wear clothes have a muhapati, which is a square or rectangular piece of cloth of a prescribed measurement, either in their hand or tied on their face covering the mouth. Svetambara ascetics have an Ogho or Rajoharan (a broom of woolen threads) to clean insects around their sitting place or while they are walking. Digambara ascetics have a Morpichhi and a Kamandal in their hands. This practice may vary among different sects of Jains but essential principle remains the same to limit needs.

Judaism

Roman Catholicism

_Roman_Catholic_Singing.jpg)

Pope John Paul II in his Post-Apostolic Exhortation Vita consecrata (1996) says concerning the religious habit of consecrated persons:

§25 … The Church must always seek to make her presence visible in everyday life, especially in contemporary culture, which is often very secularized and yet sensitive to the language of signs. In this regard the Church has a right to expect a significant contribution from consecrated persons, called as they are in every situation to bear clear witness that they belong to Christ.

Since the habit is a sign of consecration, poverty and membership in a particular Religious family, I join the Fathers of the Synod in strongly recommending to men and women religious that they wear their proper habit, suitably adapted to the conditions of time and place.

Where valid reasons of their apostolate call for it, Religious, in conformity with the norms of their Institute, may also dress in a simple and modest manner, with an appropriate symbol, in such a way that their consecration is recognizable.

Institutes which from their origin or by provision of their Constitutions do not have a specific habit should ensure that the dress of their members corresponds in dignity and simplicity to the nature of their vocation.

Nuns

The religious habit of Roman Catholic nuns typically consists of the following elements:

- Apron: A variety of styles of aprons can be worn over the habit to protect it during work activities.

- Cincture: The habit is often secured around the waist with a belt made of woven black wool.

- Card: This stiff black covering is worn over the coif when the nun leaves the convent to prevent the coif from becoming wet or soiled.

- Coif: This is the garment's headpiece and includes the white cotton cap secured by a bandeau and a white wimple or guimpe of starched linen, cotton, or (today) polyester to cover the cheeks and neck. It is sometimes covered by a thin layer of black crêpe. The cornette was another type of coif.

- Tunic: This is the central piece of the habit. It is a loose dress made of serge fabric pleated at the neck and draping to the ground. It can be worn pinned up in the front or in the back to allow the nun to work.

- Scapular: This symbolic apron hangs from both front and back; it is worn over the tunic, and Benedictine nuns also wear it over the belt, whereas some other orders wear it tied under the belt.

- Sleeves: The habit contains two sets of sleeves, the larger of which can be worn folded up for work or folded down for ceremonial occasions or whenever entering a chapel.

- Underskirts: The complete vestment includes two underskirts, a top skirt of black serge trimmed with cord and a bottom skirt of black cotton.

- Veil: This element is worn pinned over the coif head coverings and could be worn down to cover the face or up to expose it. The headpiece sometimes includes a white underveil as well.

Other accessories:

- Cross: A cross of silver traditionally hangs from a black cord around the nun's neck.

- Ring: Nuns who have taken final or "perpetual" vows indicate this status by wearing a simple silver ring on the left hand.

- Rosary: The nun's rosary of wooden beads and metal links hangs from the belt by small hooks.

- Shoes: Simple functional black shoes are the usual footwear, except for those in discalced orders who wear sandals or even go barefoot.

- Suitcase: Nuns often travel with a small black hand-held bag containing personal items and toiletries.

Different orders adhered to different styles of dress; these styles have changed over time. In the 12th century the German abbess Hildegard von Bingen, for example, advocated a style for her nuns that included extravagant and lavish white silk habits worn with golden head pieces designed to present the nun to Christ in her most beautiful form.

Priests

Usually, priests wear black or another dark color along with a white clerical collar. A cassock is worn in more formal situations. White may be worn in warmer climates. A priest is ceremonially given their habit, and it symbolizes that they are a part of the church. Also, a ferraiolo (a kind of cope) is worn along with the cassock on very formal occasions, priests also traditionally wear a biretta on the head.

Gallery

The religious habit of the Carmelite Order is brown and includes the Scapular of Our Lady of Mount Carmel (also known as Brown Scapular).

The religious habit of the Carmelite Order is brown and includes the Scapular of Our Lady of Mount Carmel (also known as Brown Scapular). The religious habit of the Sisters of the Good Shepherd (and also of the Sisters from the Order of Our Lady of Charity) is white, with a white scapular, a black veil and a large silver heart on the breast.

The religious habit of the Sisters of the Good Shepherd (and also of the Sisters from the Order of Our Lady of Charity) is white, with a white scapular, a black veil and a large silver heart on the breast. The religious habit of the Sisters of Mary Reparatrix is white, with a blue scapular, a white and blue veil and a large golden heart on the breast.

The religious habit of the Sisters of Mary Reparatrix is white, with a blue scapular, a white and blue veil and a large golden heart on the breast. The religious habit of the Norbertine Sisters of the Order of Canons Regular of Prémontré.

The religious habit of the Norbertine Sisters of the Order of Canons Regular of Prémontré. The religious habit of the Franciscan Order of Friars Minor and Friars Minor Capuchin is usually brown or gray; the habit of the Order of Friars Minor Conventual and Third Order Regular is black, although the Order of Friars Minor Conventual is returning to the grey habit worldwide.

The religious habit of the Franciscan Order of Friars Minor and Friars Minor Capuchin is usually brown or gray; the habit of the Order of Friars Minor Conventual and Third Order Regular is black, although the Order of Friars Minor Conventual is returning to the grey habit worldwide.- The religious habit of the Benedictines is black (the style varies depending upon the monastery).

The religious habit of the Carthusians is white (a novice wears a black cloak over the white Carthusian habit). It's also used by the Monks and Sisters of Bethlehem, of the Assumption of the Virgin and of Saint Bruno.

The religious habit of the Carthusians is white (a novice wears a black cloak over the white Carthusian habit). It's also used by the Monks and Sisters of Bethlehem, of the Assumption of the Virgin and of Saint Bruno. The religious habit of the Dominicans is black and white.

The religious habit of the Dominicans is black and white. Cistercian abbot Thomas Schoen, Ca.1900

Cistercian abbot Thomas Schoen, Ca.1900- Cistercians in their religious habit (with the black scapular).

The religious habit of the Clarisses (also known as Poor Clares) is brown, with a black veil

The religious habit of the Clarisses (also known as Poor Clares) is brown, with a black veil The religious habit of the Sisters of the Annunciation is white, with a red scapular and a black veil.

The religious habit of the Sisters of the Annunciation is white, with a red scapular and a black veil. The religious habit of the Franciscan Friars and Sisters of the Immaculate is gray-blue. (The image shown is, however, from an un-related Community)

The religious habit of the Franciscan Friars and Sisters of the Immaculate is gray-blue. (The image shown is, however, from an un-related Community) The religious habit (based on the Indian sari) of the Missionaries of Charity, founded by Mother Teresa of Calcutta.

The religious habit (based on the Indian sari) of the Missionaries of Charity, founded by Mother Teresa of Calcutta. The religious habit of the Trinitarian Order is white with a distinctive cross with a blue horizontal bar and a red vertical bar.

The religious habit of the Trinitarian Order is white with a distinctive cross with a blue horizontal bar and a red vertical bar. The religious habit of the Sisters of the Incarnate Word and Blessed Sacrament is white, with a red scapular and a black veil.

The religious habit of the Sisters of the Incarnate Word and Blessed Sacrament is white, with a red scapular and a black veil. Oratorians wear roughly the same vestments as parish priests. The distinctive Oratorian clerical collar consists of white cloth that folds over the collar all around the neck.

Oratorians wear roughly the same vestments as parish priests. The distinctive Oratorian clerical collar consists of white cloth that folds over the collar all around the neck. Nuns belonging to the Daughters of Charity

Nuns belonging to the Daughters of Charity Religious habit of a Trappist monk.

Religious habit of a Trappist monk.- Religious habit of a Premonstratensian canon.

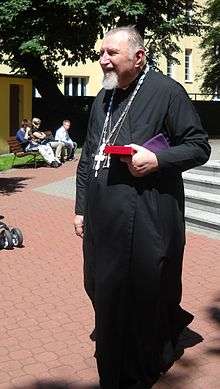

Pauline Pius Przeździecki

Pauline Pius Przeździecki The Hieronymites wear a white tunic with a brown, hooded scapular and a brown mantle

The Hieronymites wear a white tunic with a brown, hooded scapular and a brown mantle.svg.png) The habit used by the Hieronymites monks (Order of Saint Jerome)

The habit used by the Hieronymites monks (Order of Saint Jerome) The Mercedarians wear white.

The Mercedarians wear white.

Shinto

In Japan, various types of very traditional dress are worn by Shinto priests, often dating to styles worn by nobles during the Nara period or Heian period.

- Hakama (袴) - a type of traditional Japanese clothing, originally worn only by men, but today they are worn by both sexes. There are two types, divided umanori (馬乗り, "horse-riding hakama") and undivided andon bakama (行灯袴, "lantern hakama"). The umanori type have divided legs, similar to trousers, but both types appear similar. Hakama are tied at the waist and fall approximately to the ankles, and are worn over a kimono (hakamashita), with the kimono then appearing like a shirt.

- Jōe (浄衣) is a garment worn in Japan by people attending religious ceremonies and activities, including Buddhist and Shinto related occasions. Not only Shinto and Buddhist priests can be found wearing Jōe at rituals, but laymen as well, for example when participating in pilgrimage such as the Shikoku Pilgrimage. The garment is usually white or yellow and is made of linen or silk depending on its kind and use. The Shinto priest who wears the jōe is attired in a peaked cap called tate-eboshi, an outer tunic called the jōe proper, an outer robe called jōe no sodegukuri no o, an undergarment called hitoe, ballooning trousers called sashinuki or nubakama, and a girdle called jōe no ate-obi.

See also

- Degrees of Eastern Orthodox monasticism

- Tonsure

- Religious dress

- Zucchetto

Footnotes

- Kieschnick, John. The Impact of Buddhism on Chinese Material Culture. Princeton University Press, Oxfordshire, 2003. p. 90.

- Kieschnick, John. The Impact of Buddhism on Chinese Material Culture. Princeton University Press, Oxfordshire, 2003. p. 89.

- Hino, Shoun. Three Mountains and Seven Rivers. 2004. p. 55

- Hino, Shoun. Three Mountains and Seven Rivers. 2004. pp. 55-56

- Sujato, Bhante (2012), Sects & Sectarianism: The Origins of Buddhist Schools, Santipada, p. i, ISBN 9781921842085

- Mohr, Thea. Tsedroen, Jampa. Dignity and Discipline: Reviving Full Ordination for Buddhist Nuns. 2010. p. 266

- Dudjom Rinpoche Perfect Conduct: Ascertaining the Three Vows. 1999. p. 16

- Dudjom Rinpoche Perfect Conduct: Ascertaining the Three Vows. 1999. p. 16

- Kieschnick, John. The Impact of Buddhism on Chinese Material Culture. Princeton University Press, Oxfordshire, 2003. p. 89.

Further reading

- Sally Dwyer-McNulty, Common Threads: A Cultural History of Clothing in American Catholicism. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

External links

- New Catholic Dictionary

- Images of medieval monks and nuns in the dress of their Orders. (Public Domain images and text.)

- Many photographs of nuns and sisters in the dress of their respective orders.

- Catholic Sisters International Collection, University of Dayton Special Collections (Photographs of reproductions of over 130 religious habits)