Corset

A corset is a garment worn to hold and train the torso into a desired shape, traditionally a smaller waist or larger bottom, for aesthetic or medical purposes (either for the duration of wearing it or with a more lasting effect), or support the breasts. Both men and women are known to wear corsets, though this item was for many years an integral part of women's wardrobes.

Since the late 20th century, the fashion industry has borrowed the term "corset" to refer to tops which, to varying degrees, mimic the look of traditional corsets without acting as them. While these modern corsets and corset tops often feature lacing or boning, and generally imitate an historical style of corsets, they have very little, if any, effect on the shape of the wearer's body. Genuine corsets are usually made by a corsetmaker and are frequently fitted to the individual wearer.

Etymology

The word corset is a diminutive of the Old French word cors (meaning "body", and itself derived from the Latin corpus): the word therefore means "little body". The craft of corset construction is known as corsetry, as is the general wearing of them. (The word corsetry is sometimes also used as a collective plural form of corset). Someone who makes corsets is a corsetier or corsetière (French terms for a man and for a woman maker, respectively), or sometimes simply a corsetmaker.

In 1828, the word corset came into general use in the English language. The word was used in The Ladies Magazine to describe a "quilted waistcoat" that the French called un corset. It was used to differentiate the lighter corset from the heavier stays of the period.

Uses

Fashion

The most common and well-known use of corsets is to slim the body and make it conform to a fashionable silhouette. For women, this most frequently emphasizes a curvy figure by reducing the waist and thereby exaggerating the bust and hips. However, in some periods, corsets have been worn to achieve a tubular straight-up-and-down shape, which involved minimizing the bust and hips.

For men, corsets are more customarily used to slim the figure. However, there was a period from around 1820 to 1835 – and even until the late 1840s in some instances – when a wasp-waisted figure (a small, nipped-in look to the waist) was also desirable for men; wearing a corset sometimes achieved this.

An "overbust corset" encloses the torso, extending from just under the arms toward the hips. An "underbust corset" begins just under the breasts and extends down toward the hips. A "longline corset" – either overbust or underbust – extends past the iliac crest, or the hip bone. A longline corset is ideal for those who want increased stability, have longer torsos, or want to smooth out their hips. A "standard" length corset will stop short of the iliac crest and is ideal for those who want increased flexibility or have a shorter torso. Some corsets, in very rare instances, reach the knees. A shorter kind of corset that covers the waist area (from low on the ribs to just above the hips), is called a waist cincher. A corset may also include garters to hold up stockings; alternatively, a separate garter belt may be worn.

Traditionally, a corset supports the visible dress and spreads the pressure from large dresses, such as the crinoline and bustle. At times, a corset cover is used to protect outer clothes from the corset and to smooth the lines of the corset. The original corset cover was worn under the corset to provide a layer between it and the body. Corsets were not worn next to the skin, possibly due to difficulties with laundering these items during the 19th century, as they had steel boning and metal eyelets that would rust. The corset cover was generally in the form of a light chemise, made from cotton lawn or silk. Modern corset wearers may wear corset liners for many of the same reasons. Those who lace their corsets tightly use the liners to prevent burn on their skin from the laces.

People with spinal problems, such as scoliosis, or with internal injuries, may be fitted with a back brace, which is similar to a corset. However, a back brace is not the same thing as a corset. This is usually made of plastic and or metal. A brace is used to push the curves so that they don't progress, and sometimes they lower the curves. Braces are used mostly in children and adolescents, as they have a higher chance of the curves getting worse. Artist Andy Warhol was shot in 1968 and never fully recovered; he wore a corset for the rest of his life.[1]

Fetish

Aside from fashion and medical uses, corsets are also used in sexual fetishism, most notably in BDSM activities. In BDSM, a submissive may be required to wear a corset, which would be laced very tightly and restrict the wearer to some degree. A dominant may also wear a corset, often black, but for entirely different reasons, such as aesthetics. A specially designed corset, in which the breasts and vulva are exposed, can be worn during vanilla sex or BDSM activities.

Medical

A corset brace is a lumbar support that is used in the prevention and treatment of low-back pain.[2]

Construction

Corsets are typically constructed of a flexible material (like cloth, particularly coutil, or leather) stiffened with boning (also called ribs or stays) inserted into channels in the cloth or leather. In the 18th and early 19th century, thin strips of baleen (also known as whalebone) were favoured for the boning.[3][4] Plastic is now the most commonly used material for lightweight, faux corsets and the majority of poor-quality corsets. Spring and/or spiral steel or synthetic whalebone is preferred for stronger and generally better quality corsets. Other materials used for boning have included ivory, wood, and cane. (By contrast, a girdle is usually made of elasticized fabric, without boning.)

Corsets are held together by lacing, usually (though not always) at the back. Tightening or loosening the lacing produces corresponding changes in the firmness of the corset. Depending on the desired effect and time period, corsets can be laced from the top down, from the bottom up, or both up from the bottom and down from the top, using two laces that meet in the middle. In the Victorian heyday of corsets, a well-to-do woman's corset laces would be tightened by her maid, and a gentleman's by his valet. However, Victorian corsets also had a buttoned or hooked front opening called a busk. If the corset was worn loosely, it was possible to leave the lacing as adjusted and take the corset on and off using the front opening. (If the corset is worn snugly, this method will damage the busk if the lacing is not significantly loosened beforehand). Self-lacing may be very difficult where the aim is extreme waist reduction (see below). The type of corset and bodice lacing became a refined mark of class; women who could not afford servants often wore front-laced bodices.

Comfort

In the past, a woman's corset was usually worn over a chemise, a sleeveless low-necked gown made of washable material (usually cotton or linen). It absorbed perspiration and kept the corset and the gown clean. In modern times, a tee shirt, camisole or corset liner may be worn.

Moderate lacing is not incompatible with vigorous activity. During the second half of the 19th century, when corset wearing was common among women, sport corsets were specifically designed for wear while bicycling, playing tennis, or horseback riding, as well as for maternity wear.

Waist reduction

.jpg)

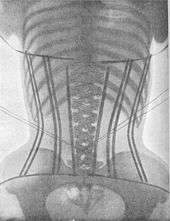

By wearing a tightly-laced corset for extended periods, known as tightlacing or waist training, men and women can learn to tolerate extreme waist constriction and eventually reduce their natural waist size. Although petite women are often able to get down to a smaller waist in absolute numbers, women with more fat are typically able to reduce their waists by a larger percentage. Although many different sizes were used, the smallest sizes that were popularly used were 16, 17 and 18 inches.[5] Some women were so tightly laced that they could breathe only with the top part of their lungs. This caused the bottom part of their lungs to fill with mucus . Symptoms of this include a slight but persistent cough, as well as heavy breathing, causing a heaving appearance of the bosom. Until 1998, the Guinness Book of World Records listed Ethel Granger as having the smallest waist on record at 13 inches (33 cm).[6] After 1998, the category changed to "smallest waist on a living person". Cathie Jung took the title with a waist measuring 15 inches (38 cm). Other women, such as Polaire, also have achieved such reductions (16 inches (41 cm) in her case). However, these are extreme cases. Corsets were and are still usually designed for support, with freedom of body movement an important consideration in their design.

History

For nearly 500 years, women's primary means of support was the corset, with laces and stays made of whalebone or metal. Other researchers have found evidence of the use of corsets in early Crete ( Minoan civilization ).[7]:5

The corset has undergone many changes. Originally, it was known as "a pair of bodys" in the late 16th century.[8] It was a simple bodice, stiffened with boning of reed or whalebone that could be under or outer wear.[7][9] A busk made of wood, horn, whalebone, metal or ivory further reinforced the central front. Bodies during the 16th and 17th centuries could be front or back lacing. During the late seventeenth century the English term "pair of bodies" was replaced with the term "stays", which was generally used during the 18th century.[10] Stays essentially turned the upper torso into a cone or cylinder shape.[11] In the 17th century, tabs (called "fingers") at the waist were added.

Stays evolved in the 18th century when whalebone was used more, and there was more boning used in the garment. The shape of the stays changed as well. While the stays were low and wide in the front, they could reach as high as the upper shoulder in the back. Stays could be strapless or use shoulder straps. The straps of the stays were generally attached in the back and tied at the front sides.

The purpose of 18th century stays was to support the bust and confer the fashionable conical shape while drawing the shoulders back. At this time, the eyelets were reinforced with stitches and were not placed across from one another, but instead staggered. This allowed the stays to be spiral laced. One end of the stay lace was inserted and knotted in the bottom eyelet; the other end was wound through the stays' eyelets and tightened on the top. Tight-lacing was not the purpose of stays during this time period. Women in all societal levels, from ladies of the court to street vendors, wore stays.

During this time period, there is evidence of a variant of stays, called "jumps", which were looser than stays with attached sleeves, like a jacket.[7]:27

Woman's corset (stays) c. 1730–1740. Silk plain weave with supplementary weft-float patterning, stiffened with baleen; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, M.63.24.5.[12]

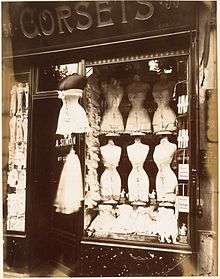

Woman's corset (stays) c. 1730–1740. Silk plain weave with supplementary weft-float patterning, stiffened with baleen; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, M.63.24.5.[12] A corset from a 1901 French magazine

A corset from a 1901 French magazine Polaire was famous for her tiny, corseted waist, which was sometimes reported to have a circumference no greater than 16 inches (41 cm)

Polaire was famous for her tiny, corseted waist, which was sometimes reported to have a circumference no greater than 16 inches (41 cm) Bianca Lyons shows the increased female curves emphasized by corsets, circa 1902

Bianca Lyons shows the increased female curves emphasized by corsets, circa 1902 A woman models a corset in this 1898 photograph

A woman models a corset in this 1898 photograph.jpg) Amanda Nielsen in a corset

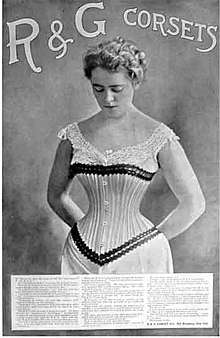

Amanda Nielsen in a corset An award-winning ad for R & G Corset Company from the back cover of the October 1898 Ladies' Home Journal

An award-winning ad for R & G Corset Company from the back cover of the October 1898 Ladies' Home Journal Group of five corsets, late 19th and early 20th century; Peloponnesian Folklore Foundation.

Group of five corsets, late 19th and early 20th century; Peloponnesian Folklore Foundation.

Corsets were originally quilted waistcoats, which French women wore as an alternative to stiff corsets.[7]:29 They were only quilted linen, laced in the front, and un-boned. This garment was meant to be worn on informal occasions, while stays were worn for court dress. In the 1790s, stays began to fall out of fashion. This development coincided with the French Revolution and the adoption of neoclassical styles of dress. It was the men, Dandies, who began to wear corsets.[7]:36 The fashion persisted through the 1840s, though after 1850 men who wore corsets claimed they needed them for back pain.[7]:39

In the early 19th century, when gussets were added for room for the bust, stays became known as corsets. They also lengthened to the hip and the lower tabs were replaced by gussets at the hip and had less boning. The shoulder straps disappeared in the 1840s for normal wear.[8]

In the 1820s, fashion changed again, with the waistline lowered back to almost the natural position. This was to allow for more ornamentation on the bodice, which in turn saw the return of the corset to modern fashion. Corsets began to be made with some padding and more boning. Some women made their own, while others bought their corsets. Corsets were one of the first mass-produced garments for women. Corsets began to be more heavily boned in the 1840s. By 1850, steel boning became popular.

With the advent of metal eyelets, tight lacing became possible. The position of the eyelets changed. They were situated across from one another at the back. The front was fastened with a metal busk in front. Corsets were mostly white. The corsets of the 1850s–1860s were shorter than the corsets of the 19th century through 1840s. This was because of a change in the silhouette of women's fashion. The 1850s and 1860s emphasized the hoopskirt. After the 1860s, when the hoop fell out of style, the corset became longer to mold the abdomen, exposed by the new lines of the princess or cuirass style.

For dress reformists of the 1800s, corsets were a dangerous moral ‘evil’, promoting promiscuous views of female bodies and superficial dalliance into fashion whims. The obvious health risks, including damaged and rearranged internal organs, compromised fertility; weakness and general depletion of health were also blamed on excessive corsetry. Eventually, the reformers' critique of the corset joined a throng of voices clamoring against tightlacing, which became gradually more common and extreme as the 19th century progressed. Preachers inveighed against tightlacing, doctors counseled patients against it and journalists wrote articles condemning the vanity and frivolity of women who would sacrifice their health for the sake of fashion. Whereas for many corseting was accepted as necessary for beauty, health, and an upright military-style posture, dress reformists viewed tightlacing as vain and, especially at the height of the era of Victorian morality, a sign of moral indecency.

American women active in the anti-slavery and temperance movements, with experience in public speaking and political agitation, demanded sensible clothing that would not restrict their movement.[13] While support for fashionable dress contested that corsets maintained an upright, ‘good figure’, as a necessary physical structure for moral and well-ordered society, these dress reformists contested that women's fashions were not only physically detrimental, but “the results of male conspiracy to make women subservient by cultivating them in slave psychology.”[14][15] They believed a change in fashions could change the whole position of women, allowing for greater social mobility, independence from men and marriage, the ability to work for wages, as well as physical movement and comfort.[16]

In 1873 Elizabeth Stuart Phelps Ward wrote:

Burn up the corsets! ... No, nor do you save the whalebones, you will never need whalebones again. Make a bonfire of the cruel steels that have lorded it over your thorax and abdomens for so many years and heave a sigh of relief, for your emancipation I assure you, from this moment has begun.[17]

Despite these protests, little changed in restrictive fashion and undergarments by 1900. During the Edwardian period, the straight front corset (also known as the S-Curve corset) was introduced. This corset was straight in front with a pronounced curve at the back that forced the upper body forward and the derrière out. This style was worn from 1900 to 1908.[7]:144 This style of corset was originally conceived as a health corset, which was a type of corset that was made of wool and reinforced with cording and promoted the healthy benefits of wearing wool next to skin. This was sold as an alternative to the boned corset.[18] However the S-Curve corset became the framework for many ornate fashions from the late 1890s and 1900s.

The corset reached its longest length in the early 20th century. At first, the longline corset reached from the bust down to the upper thigh. There was also a style of longline corset that started under the bust, and necessitated the wearing of a brassiere. This style was meant to complement the new silhouette. It was a boneless style, much closer to a modern girdle than the traditional corset. The longline style was abandoned during World War I.

The corset fell from fashion in the 1920s in Europe and North America, replaced by girdles and elastic brassieres, but survived as an article of costume. Originally an item of lingerie, the corset has become a popular item of outerwear in the fetish, BDSM and goth subcultures. In the fetish and BDSM literature, there is often much emphasis on tightlacing, and many corset makers cater to the fetish market.

Outside the fetish community, living history re-enactors and historic costume enthusiasts still wear stays and corsets according to their original purpose to give the proper shape to the figure when wearing historic fashions. In this case, the corset is underwear rather than outerwear. Skilled corset makers are available to make reproductions of historic corset shapes or to design new styles.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, there was a brief revival of the corset in the form of the waist cincher sometimes called a "waspie". This was used to give the hourglass figure as dictated by Christian Dior's "New Look". However, use of the waist cincher was restricted to haute couture, and most women continued to use girdles. Waspies were also met with push back from women's organizations in the United States as well as female members of the London Parliament as corsetry had been forbidden under rationing during World War II.[18] This revival was brief, as the New Look gave way to a less dramatically-shaped silhouette.

In 1968 at the feminist Miss America protest, protestors symbolically threw a number of feminine products into a "Freedom Trash Can." These included corsets,[19] which were among items the protestors called "instruments of female torture"[20] and accouterments of what they perceived to be enforced femininity.

Since the late 1980s, the corset has experienced periodic revivals, all which have usually originated in haute couture and have occasionally trickled through to mainstream fashion. Fashion designer Vivienne Westwood's use of corsets contributed to the push-up bust trend that lasted from the late 1980s throughout the 1990s.[18] These revivals focus on the corset as an item of outerwear rather than underwear. The strongest of these revivals was seen in the Autumn 2001 fashion collections and coincided with the release of the film Moulin Rouge!; the costumes featured many corsets as characteristic of the era. Another fashion movement, which has renewed interest in the corset, is the steampunk culture that utilizes late-Victorian fashion shapes in new ways.

Special types

There are some special types of corsets and corset-like devices which incorporate boning.

Corset dress

A corset dress (also known as hobble corset because it produces similar restrictive effects to a hobble skirt) is a long corset. It is like an ordinary corset, but it is long enough to cover the legs, partially or totally. It thus looks like a dress, hence the name. A person wearing a corset dress can have great difficulty in walking up and down the stairs (especially if wearing high-heeled footwear) and may be unable to sit down if the boning is too stiff.

Other types of corset dresses are created for unique high fashion looks by a few modern corset makers. These modern styles are functional as well as fashionable and are designed to be worn with comfort for a dramatic look.

Neck corset and Collar

A neck corset is a type of posture collar incorporating stays and it is generally not considered to be a true corset. This type of corset and its purpose of improving posture does not have long term results. Since certain parts of the neck are being pulled towards the head, a band in the neck called the platysmal band will most likely disappear.[21] Like the neck corset, a collar serves some of the same purposes. According to G. J. Huston, collars are worn to allow minimal neck movement after road accidents. Furthermore, he concluded that wearing a collar in order to improve the structure of the neck was more cheap than physiotherapy.[22] Neck corsets and collars have become a fashion statement instead of assets to improve posture. As you can see in the image to the right, this individual is wearing a matching corset and collar.

See also

- Bustier

- Corset controversy

- Dudou, a Chinese undershirt sometimes known as a "corset"

- Fainting room

- Fetish clothing

- Gibson Girl

- Tightlacing

- Waist cincher

References

- Notes

- "Warhol: Biography". 2013-01-06. Archived from the original on 2013-01-06. Retrieved 2017-11-10.

- Lumbar supports for the prevention and treatment of low-back pain

- Doyle, R. (1997). Waisted Efforts, An Illustrated Guide to Corset Making. Sartorial Press Publications. ISBN 0-9683039-0-0.

- Waugh, Norah (1990). Corsets and Crinolines. Routledge. ISBN 978-0878305261.

- "History of Tightlacing". Archived from the original on November 15, 2015. Retrieved August 11, 2015.

- Vogue cover model shocks with 33cm waist MADONNA magazine from August 31st, 2011

- Steele, Valerie (2001). The Corset: A Cultural History. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09953-3.

- Waugh, Norah (December 1, 1990). Corsets and Crinolines. Routledge. ISBN 0-87830-526-2.

- Bendall, Sarah (2019-01-01). "Bodies or Stays? Underwear or Outerwear? Seventeenth-century Foundation Garments explained". Sarah A Bendall. Retrieved 2020-07-18.

- Bendall, Sarah (2019-01-01). "Bodies or Stays? Underwear or Outerwear? Seventeenth-century Foundation Garments explained". Sarah A Bendall. Retrieved 2020-07-18.

- Gupta, Richa (February 13, 2013). Corset. p. 6.

- Takeda, Sharon Sadako; Spilker, Kaye Durland (2010). Fashioning Fashion: European Dress in Detail, 1700–1915. Prestel USA. p. 76. ISBN 978-3-7913-5062-2.

- "Woman's dress, a question of the day". Early Canadiana Online. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- Dress and Morality by Aileen Ribeiro, (Homes and Meier Publishers Inc: New York. 1986) p. 134

- Riegel, Robert E. (1963). "Women's Clothes and Women's Right". American Quarterly. 15: 390. doi:10.2307/2711370.

- Riegel, Robert E. (1963). "Women's Clothes and Women's Right". American Quarterly. 15: 391.

- Phelps, Elizabeth (1873). What to Wear. Boston: Osgood. p. 79.

- Stevenson, NJ (2011). The Chronology of Fashion. London: The Ivy Press.

- Dow, Bonnie J. (Spring 2003). "Feminism, Miss America, and Media Mythology". Rhetoric & Public Affairs. 6 (1): 127–149. doi:10.1353/rap.2003.0028.

- Duffett, Judith (October 1968). WLM vs. Miss America. Voice of the Women's Liberation Movement. p. 4.

- Tonnard, Patrick; Verpaele, Alexis; Monstrey, Stan; Van Landuyt, Koen; Blondeel, Philippe; Hamdi, Moustapha; Matton, Guido (May 2002). "Minimal access cranial suspension lift: a modified S-lift". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 109 (6): 2074–2086. doi:10.1097/00006534-200205000-00046. ISSN 0032-1052. PMID 11994618.

- Huston, G.J. (1988). "Collars and Corsets". British Medical Journal. 296 (6617): 276. doi:10.1136/bmj.296.6617.276. JSTOR 29529544. PMC 2544783.

Further reading

- Doyle, R. (1997). Waisted Efforts: An Illustrated Guide to Corset Making. Sartorial Press Publications. ISBN 0-9683039-0-0.

- Kunzle, David (2004). Fashion and Fetishism. Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-3808-0.

- Steele, Valerie (2001). The Corset: A Cultural History. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09953-3.

- Utley, Larry; Carey-Adamme, Autumn (2002). Fetish Fashion: Undressing the Corset. Green Candy Press. ISBN 1-931160-06-6.

- Waugh, Norah (1990). Corsets and Crinolines. Routledge. ISBN 0-87830-526-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Corsets. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Corset |

| Look up corset in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |