Chlamys

The chlamys (Ancient Greek: χλαμύς : chlamýs, genitive: χλαμύδος : chlamydos) was a type of an ancient Greek cloak.[1] By the time of the Byzantine Empire it was, although in a much larger form, part of the state costume of the emperor and high officials. It survived as such until at least the 12th century AD.

The ephaptis (Ancient Greek: ἐφαπτίς) was a similar garment, typically worn by infantrymen.[2]

Ancient Greece

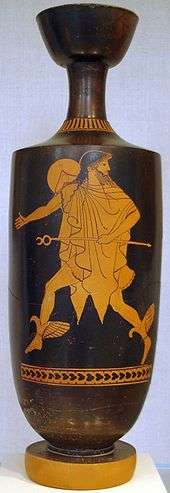

The chlamys was made from a seamless rectangle of woolen material about the size of a blanket, usually bordered. It was normally pinned with a fibula at the right shoulder. Originally it was wrapped around the waist like a loincloth, but by the end of the 5th century BC it was worn over the elbows. It could be worn over another item of clothing but was often the sole item of clothing for young soldiers and messengers, at least in Greek art. As such, the chlamys is the characteristic garment of Hermes (Roman Mercury), the messenger god usually depicted as a young man.

The chlamys was typical Greek military attire from the 5th to the 3rd century BC. As worn by soldiers, it could be wrapped around the arm and used as a light shield in combat.

Byzantine period

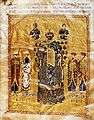

The chlamys continued into the Byzantine period, when it was often much larger and usually worn sideways, at least by emperors, and likely made of silk. It was held on with a fibula brooch at the wearer's right shoulder and nearly reached the ground at front and back. With the even grander loros costume, the "chlamys costume" was the ceremonial wear of Byzantine emperors, and the only option for high officials on very formal occasions.[3] It is generally less common in surviving imperial portraits than the loros shown on coins, though the large numbers of Byzantine coins that survive provide many examples, with the fibula often the main indication in bust-length depictions.

At the two edges of the cloak were large panels in a contrasting colour called tablia (sing. tablion), beginning about level with the armpit and reaching down to about the waist; typically only the one on the wearer's left is seen in portraits. The emperor alone could wear a purple chlamys with gold tablia; officials sometimes wore white with purple tablia, as the two beside Justinian I at Ravenna do.[4] In the miniature shown below the 11th-century emperor wears his open to the side, presumably to allow access to his sword, but the three officials have the opening at the centre of their bodies.

By the Middle Byzantine period all parts of the chlamys were highly decorative, with bright patterned Byzantine silk and tablia and borders heavily embroidered and encrusted with gems.[5] In the 12th century it seems to have begun to fall from favour, although it continued to be shown on coins until the 14th century, which was perhaps long after it was actually worn. Some high officials seem to have continued to wear a version of it long after the emperors had abandoned it.[6] While the loros tended to represent the emperor in his religious role, the chlamys represented his secular functions as head of state, head of the administrative corps of the empire, and giver of justice.[7]

Among women only the empress is recorded as wearing a chlamys; she was presented with it during the coronation ceremony. In art it is much rarer to see an empress in it than in a loros, but in the well-known ivory Romanos ivory (BnF, Paris) Eudokia Makrembolitissa wears one while her husband Constantine X Doukas (r. 1059–1067) wears the loros.[8]

Gallery

A chlamys-wearing torso, possibly of Alexander

A chlamys-wearing torso, possibly of Alexander Ptolemy III as Hermes wearing the chlamys

Ptolemy III as Hermes wearing the chlamys Chlamys-wearing youth (Roman, 2nd century AD)

Chlamys-wearing youth (Roman, 2nd century AD)- Model wearing a 19th-century re-creation

Justinian I and ministers wear early Byzantine ceremonial chlamydes, Ravenna mosaic.

Justinian I and ministers wear early Byzantine ceremonial chlamydes, Ravenna mosaic. At the basilica of Sant'Apollinare in Classe in Ravenna, the Heraclian Emperor Constantine IV Pogonatus wears a chlamys similar to that of Justinian I, the namesake of his son and successor.

At the basilica of Sant'Apollinare in Classe in Ravenna, the Heraclian Emperor Constantine IV Pogonatus wears a chlamys similar to that of Justinian I, the namesake of his son and successor..jpg) On the reverse of this solidus of Leo V the Armenian, the Emperor's son Constantine wears a ceremonial chlamys, 813-820

On the reverse of this solidus of Leo V the Armenian, the Emperor's son Constantine wears a ceremonial chlamys, 813-820 11th-century emperor wears the chlamys, as do three of his officials.

11th-century emperor wears the chlamys, as do three of his officials.- Romanos ivory, 11th century with a rare female chlamys, and the emperor in the loros costume

References and sources

- References

- Ancient Greek Dress Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–2013. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- Parani, 11-18

- Parani, 12

- Parani, 12-13

- Parani, 13-16

- Parani, 16-18

- Parani, 12, 17-18

- Sources

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chlamydes. |

- Parani, Maria G. (2003). Reconstructing the Reality of Images: Byzantine Material Culture and Religious Iconography (11th–15th Centuries. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9004124624.

- Sekunda, Nicholas (2000). Greek Hoplite 480–323 BC. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-85532-867-4

- Ridgway, S. Brunilde (1990). Hellenistic Sculpture: The Styles of ca. 331–200 B.C. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-299-16710-0