Bou Inania Madrasa

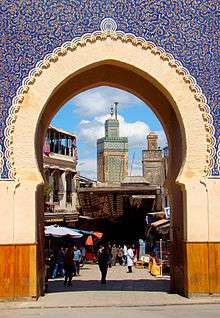

The Madrasa Bou Inania (also Bu Inaniya, المدرسة أبو عنانية بفاس al-madrasa ʾAbū ʿInānīya bi-Fās) is a madrasa in Fes, Morocco, founded in AD 1350–56 by Abu Inan Faris.[1] It is widely acknowledged as a high point of Marinid architecture and of historic Moroccan architecture generally.[2][3][4][5]

| Bou Inania Madrasa | |

|---|---|

المدرسة البوعنانية | |

Main courtyard and minaret. | |

| |

| General information | |

| Status | historic site, tourist attraction, active mosque |

| Type | madrasa and mosque |

| Architectural style | Marinid, Moroccan, Islamic |

| Location | Fes, Morocco |

| Coordinates | |

| Named for | Sultan Abu Inan Faris |

| Construction started | 28 December 1350 CE (28 Ramadan 751 AH) |

| Completed | 1355 CE (756 AH) |

| Technical details | |

| Material | cedar wood, brick, stucco, tile |

| Floor count | 2 |

History

Founder and patron: Sultan Abu Inan

The name Bou Inania (Bū 'Ināniya) is derived from the name of its founder, the Marinid sultan Faris ibn Ali Abu Inan al-Mutawakkil (generally Abou Inan or Abu Inan for short).[2][6] It was originally named the Madrasa al-Muttawakkiliya but the name Madrasa Bu Inania has been retained instead.[7] He was the son and successor of Sultan Abu al-Hasan, under whose reign the Marinid empire reached its apogee and expanded all the way to Tunis in the east.[8][6] Abu Inan, who rebelled against his father and declared himself sultan in 1348, did not manage to hold onto all these new eastern territories, but the Moroccan state was nonetheless prosperous during his reign.[4][8] He was assassinated by his vizier on January 10, 1358, at the age of 31.[8] His death marked the beginning of the dynasty's definitive decline, with subsequent Marinid rulers being mostly figureheads controlled by powerful viziers.[8]

Context: the role of Marinid madrasas

The Marinids were prolific builders of madrasas, a type of institution which originated in northeastern Iran by the early 11th century and was progressively adopted further west.[5] These establishments served to train Islamic scholars, particularly in Islamic law and jurisprudence (fiqh). The madrasa in the Sunni world was generally antithetical to more "heterodox" religious doctrines, including the doctrine espoused by the Almohad dynasty. As such, it only came to flourish in Morocco under the Marinid dynasty which succeeded the Almohads.[5] To the Marinids, madrasas played a part in bolstering the political legitimacy of their dynasty. They used this patronage to encourage the loyalty of Fes's influential but fiercely independent religious elites and also to portray themselves to the general population as protectors and promoters of orthodox Sunni Islam.[5][4] The madrasas also served to train the scholars and elites who operated their state's bureaucracy.[4]

The Bou Inania Madrasa was the largest and most important madrasa created by the Marinid dynasty and turned into one of the most important religious institutions of Fes and Morocco.[7][3] It was the only such madrasa to gain the status of Grand Mosque or "Friday Mosque", which meant that the Friday sermon (khutba) was delivered here like in the other most important mosques of the city.[5][4] As a result, it was fully equipped with the all the facilities of a major mosque and religious complex, in addition to extensive decoration.[7] The architecture and decoration of the madrasa is also considered to be the culmination of this type of Marinid architecture.[4]

Foundation and construction

A number of apocryphal stories about the madrasa's creation exist. One reported story claims that Abu Inan felt guilt about his violent overthrow of his father (Sultan Abu al-Hasan) and gathered a number of religious scholars to advise him on how he could redeem himself and seek forgiveness from God (Allah). They advised him to choose a location in the upper city which then served as a garbage dump and to transform it into a site of religious learning; thus, by purifying and improving a part of the city, he would do the same for his conscience.[2]

The foundation inscription of the building, located inside the prayer hall, indicates that construction on the madrasa started on December 28, 1350 CE (28 Ramadan 751 AH), and finished in 1355 (756 AH).[4]:474 The inscription also notes an extensive list of mortmain-type endowments (i.e. properties and other sources of revenue) which were dedicated to funding the madrasa's operations and which were part of its habous or waqf (an Islamic charitable trust).[4]

The construction project was known to be highly expensive due to the scale and lavishness of the building. One apocryphal anecdote claims that the sultan, upon seeing the full cost of construction presented to him by nervous construction supervisors, ripped up the accounts book and threw it in the river, while proclaiming: "What is beautiful is not expensive, no matter how large the sum."[7][2]

Later history and restorations

The madrasa has undergone numerous restorations, particularly in the 17th century after a damaging earthquake.[2] During the reign of Sultan Mulay Sliman (1792-1822), entire wall sections were reconstructed.[2] In the 20th century restorations were carried out on the madrasa's decorations.[2]

Architecture and layout

The madrasa is actually a complex of buildings that together provide the facilities required to serve as a madrasa and mosque. The main building has the outline of an irregular rectangle measuring 34.65 by 38.95 metres.[4]:474 It is located between Tala'a Kebira and Tala'a Seghira, two of the most important streets of Fes el-Bali, and is aligned with what was then considered the qibla (direction of prayer), to the southeast. This main structure includes the study areas, the mosque or prayer hall area, living quarters for students, and an ablutions room. Directly across the street to the north is another, larger, ablutions house (dar al-wuḍūʾ) with latrines. Right next to this is the Dar al-Magana or "House of the Clock", which features a famous but currently non-functional hydraulic clock on its facade.

The madrasa

Entrances

.jpg)

The madrasa has two entrances: one on Tala'a Kebira street aligned with the mihrab and the central axis of the building, and another on Tala'a Seghira at the back. The Tala'a Kebira entrance has a horseshoe arch doorway surrounded by stucco decoration. A set of stairs leads into a vestibule and then directly into the main courtyard. The vestibule is covered in the same rich ornamentation as the rest of the madrasa and has a ceiling of cedar wood carved in elaborate muqarnas.[3] Another doorway to the left of the main entrance leads directly to the outer gallery of the main courtyard and from there giving access to an ablutions room in the northeast part of the building. This room is centered around a rectangular water basin and is surrounded by other small chambers.[5][4]

The rear Tala'a Seghira entrance is marked by a carved wooden canopy above a panel of carved stucco decoration, and leads via a bending corridor to the main courtyard.[5] In this part of the building was also a Qur'anic school for children (similar to a kuttab).[3]

Main courtyard and adjoining chambers

The building is centered around a large rectangular courtyard slightly deeper than it is wide.[5] At its center is a fountain and basin to assist in ablutions, as is common in many mosque sahns.[5] The courtyard is surrounded on three sides by a narrow gallery partially hidden by wooden screens between pillars that help to uphold the walls of the floor above. The passages of the gallery lead to other rooms, mostly living cells for the madrasa students, around the courtyard.

On the east and west sides of the courtyard, aligned with the central fountain, are two large square chambers, measuring 5 metres per side, which served as classrooms.[5][4] They are entered via archways with intricate muqarnas-carved intrados, and are guarded by large cedar wood doors finely carved with geometric patterns and Arabic calligraphic inscriptions. Inside, the chambers are decorated with more stucco-carved surfaces and covered by wooden cupola with a pattern of radiating ribs.[4] These two lateral chambers have been compared with the iwans of classic madrasa architecture further east in Egypt, such as the Madrasa of Sultan Hassan in Cairo, leading to speculation that the architect was familiar with such models.[5]:293

At the northwestern and northeastern corners of the building are stairways that lead to an upper floor which is occupied by more living quarters for students, some of which have windows overlooking the courtyard.[4][5]

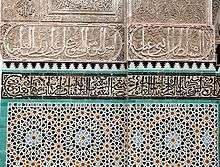

Decoration of the main courtyard

The madrasa's decoration is highly refined and echoes the style that was established by the slightly earlier and smaller, but equally ornate, Madrasa al-'Attarin and Madrasa al-Sahrij.[5][4] The style is most evident in the courtyard but repeated in other parts of the building. The lower walls and pillars are covered in elaborate zellij mosaic tilework forming complex geometric patterns, with a band of epigraphic and calligraphic tiles runs above this along most of the courtyard. The middle and upper walls above this are covered in finely-carved stucco with a harmonious variety of motifs including arabesques, muqarnas (especially around the windows), Arabic calligraphic inscriptions (particularly at the middle of pillars and around the eastern and western doorways), and more geometric patterns. The spaces between the pillars of the gallery and below the windows are highlighted with carved cedar wood elements, while the walls above the stucco decoration also transition to surfaces of cedar wood carved with more arabesque motifs and Arabic inscriptions. Lastly, the top of the walls is overshadows by a wooden canopy supported by corbels.[5][3][4]

Prayer hall or mosque area

.jpg)

Along the south edge of the courtyard runs a small canal with water drawn from the Oued el-Lemtiyyin, one of the canals branching from the Oued Fes (Fez River) which supplies the city with water.[4][9] The canal likely also served an aesthetic and possibly symbolic purpose, in addition to further assisting in ablutions.[3] The canal is crossed by two small bridges at the corners of the courtyard which give access to a prayer hall on the other side, bordering the southern side of the courtyard.[5] This mosque area is open to the courtyard via the continuation of the gallery arches around the courtyard, and its interior is thus visible to visitors albeit off-limits to non-Muslims. The interior itself is also split transversely by a row of arches resting on onyx columns.[5] The far (southern) wall is marked by the mosque's mihrab, a niche symbolizing the direction of prayer (qibla). The walls around the mihrab is surrounded by typical stucco-carved decoration. In the upper walls are windows with decorative stucco grilles inset with coloured glass. The mosque is covered by a berchla or sloped wood-frame roof seen in many other Moroccan mosques.[5]

Minaret

The minaret, made of brick rises above the northwestern corner of the madrasa.[3] This is the only minaret attached to a madrasa in Morocco.[10][11] Like most Moroccan minarets, it has a square shaft and is topped by a small secondary tower topped with a cupola and a metal finial with spheres. The four facades of the minaret are covered by slightly different variations of the darj wa-ktaf motif (vaguely similar to a fleur-de-lys or palmette shape) common to Moroccan architecture. The empty spaces inside the motif are filled with zellij mosaic tiles.[4] Above these motifs is a more extensive band of zellij running around the top of the minaret. The smaller secondary shaft is similarly decorated. This style of minaret is similar to other Marinid constructions of the era, such as the Chrabliyine Mosque built further down Tala'a Kebira street in 1342.[4]

The ablutions house (Dar al-Wudu)

Opposite the main doorway of the madrasa is the entrance to the dar al-wuḍūʾ ("house of ablutions") for washing limbs and face before prayers. Like the rest of the madrasa, it was built by Sultan Abu Inan and served both the madrasa and the wider public.[3] It is plentifully supplied with water which is used to wash away waste from the latrines included inside it. Some remnants of Marinid-era decoration in stucco and cedar wood have survived on its upper walls inside.[3]

The water clock (Dar al-Magana)

.jpg)

Also opposite the Madrasa Bou Inania is the Dar al-Magana, a house whose street facade features a famous but not fully understood hydraulic clock. The symbolic and practical importance of a clock lay in its use for determining the correct times of prayer, and the system was overseen by the mosque's muwaqqit (timekeeper). The structure is believed to have also been built by Abu Inan alongside his madrasa complex, with one chronicler (al-Djazna'i) reporting that it was completed on May 6, 1357 (14 Djumada al-awwal, 758 AH).[4]:492 The facade of the building has 13 consoles (corbels) intricately carved in cedar wood, with panels of wood-carved arabesques and stylized Kufic decoration between them. Above these are twelve windows surrounded by stucco-carved decoration, above which in turn are two rows of projecting wooden corbels. The uppermost row of consoles is longer than the ones below and presumably supported a parapet or canopy that has since disappeared.[4]

Each of the 13 consoles under the windows once supported a bronze bowl, seen in old photographs.[4][3] Historical accounts describe how at every hour a lead ball or weight fell into one of the bowls to make a ringing sound, while at the same time opening the "doors" or shutters of the corresponding window. The exact mechanism that operated this system has disappeared and its workings are unknown today. It was likely powered in some way by running water, and it appears the weights or balls may have been suspended by a lead line attached to the projecting consoles above the windows.[4] The surviving bronze bowls of the clock were removed in the later 20th century for ongoing study, though the structure itself was restored in the early 2000s.[12][4]

The minbar

The original minbar of the madrasa's mosque is today housed at the Dar Batha museum (located further west, not far from Bab Bou Jeloud), with a later replacement now present in the mosque itself.[4]:481 This original dates from 1350-1355 when the madrasa was being built, and is notable as one of the best Marinid examples of its kind.[13][4] Minbars, often described or translated as a "pulpit", was by this period a mostly symbolic object in mosques; the form of the Bou Inania minbar did not practically allow an imam to actually climb it.[4] Its form and decoration, like most minbars of Morocco after the Almoravid period, was closely inspired and derived from the famous minbar of the Kutubiyya Mosque, which was commissioned in 1137 by the Almoravid emir Ali ibn Yusuf and crafted in Cordoba, Spain (Al-Andalus).[14] That minbar established a prestigious artistic tradition, originating from formerly Umayyad Al-Andalus, which was imitated and emulated in subsequent periods, though subsequent minbars varied in their exact form and in the choice of the decorative methods.

Like the Kutubiyya minbar, the Bou Inania Minbar, made of wood (including ebony and other expensive woods), is decorated via a mix of marquetry and inlaid carved decoration.[13][4] The main decorative pattern along its major surfaces on either side is centered around eight-pointed stars, from which bands of decorated with ivory inlay then interweave and repeat the same pattern across the rest of the surface. The spaces between these bands form other geometric shapes which are filled with wood panels of intricately carved arabesques. This motif is similar to that found on the Kutubiyya minbar, and even more so to that of the slightly later minbar of the Kasbah Mosque in Marrakech (commissioned between 1189 and 1195).[13] The arch above the first step of the minbar contains an inscription, now partly disappeared, which refers to Abu Inan and his titles.[4]

References

- William J. Courtenay; Jürgen Miethke, University and Schooling in Medieval Society, (Brill, 2000), 97. – via Questia (subscription required)

- Touri, Abdelaziz; Benaboud, Mhammad; Boujibar El-Khatib, Naïma; Lakhdar, Kamal; Mezzine, Mohamed (2010). Le Maroc andalou : à la découverte d'un art de vivre (2 ed.). Ministère des Affaires Culturelles du Royaume du Maroc & Museum With No Frontiers. ISBN 978-3902782311.

- Parker, Richard (1981). A practical guide to Islamic Monuments in Morocco. Charlottesville, VA: The Baraka Press.

- Lintz, Yannick; Déléry, Claire; Tuil Leonetti, Bulle (2014). Maroc médiéval: Un empire de l'Afrique à l'Espagne. Paris: Louvre éditions. ISBN 9782350314907.

- Marçais, Georges (1954). L'architecture musulmane d'Occident. Paris: Arts et métiers graphiques.

- Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (1996). New Islamic Dynasties. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 15–17.

- Gaudio, Attilio (1982). Fès: Joyau de la civilisation islamique. Paris: Les Presse de l'UNESCO: Nouvelles Éditions Latines. p. 113. ISBN 2723301591.

- Abun-Nasr, Jamil (1987). A history of the Maghrib in the Islamic period. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521337674.

- Mohamed Mezzine "Buinaniya Madrasa" in Discover Islamic Art, Museum With No Frontiers, 2020. 2020. http://islamicart.museumwnf.org/database_item.php?id=monument;ISL;ma;Mon01;11;en

- Sheila Blair, Jonathan M. Bloom, The Art and Architecture of Islam: 1250-1800, (Yale University Press, 1994), 122.

- Fez, Andrew Petersen, Dictionary of Islamic Architecture, (Routledge, 1999), 87. – via Questia (subscription required)

- "L'horloge hydraulique de Fès pratiquement restaurée". L'Economiste (in French). 2003-07-08. Retrieved 2020-02-18.

- Carboni, Stefano (1998). "Signification historique et artistique du minbar provenant de la mosquée Koutoubia". Le Minbar de la Mosquée Kutubiyya (French ed.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Ediciones El Viso, S.A., Madrid; Ministère des Affaires Culturelles, Royaume du Maroc.

- Bloom, Jonathan (1998). "Le minbar de la mosquée Kutubiyya". Le Minbar de la Mosquée Kutubiyya (French ed.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Ediciones El Viso, S.A., Madrid; Ministère des Affaires Culturelles, Royaume du Maroc. p. 3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bou Inania Madrasa, Fes. |

- Museum with no Frontiers (retrieved November 12, 2008)

- The madrasa on archnet.org

- Patterns in Islamic art