Thami El Glaoui

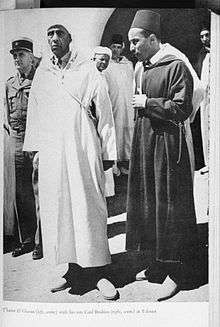

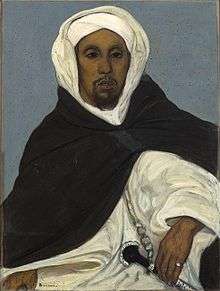

Thami El Glaoui (Arabic: التهامي الكلاوي; 1879–23 January 1956), known in English as Lord of the Atlas, was the Pasha of Marrakesh from 1912 to 1956. His family name was el Mezouari, from a title given an ancestor by Ismail Ibn Sharif in 1700, while El Glaoui refers to his chieftainship of the Glaoua (Glawa) tribe of the Berbers of southern Morocco, based at the Kasbah of Telouet in the High Atlas and at Marrakesh. El Glaoui became head of the Glaoua upon the death of his elder brother, Si el-Madani, and as an ally of the French protectorate in Morocco, conspired with them in the overthrow of Sultan Mohammed V.

Thami El Glaoui | |

|---|---|

| |

| Pasha of Marrakesh | |

| In office 1909–1911 | |

| Succeeded by | Driss Mennou |

| Pasha of Marrakesh | |

| In office 1912–1956 | |

| Preceded by | Driss Mennou |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Thami El Mezouari El Glaoui 1879 Telouet, High Atlas, Morocco |

| Died | January 23, 1956 (76-77) Marrakesh, Morocco |

| Nationality | Moroccan |

On October 25 of 1955, El-Glaoui announced his acceptance of Mohammed V's restoration as well as Morocco's independence.[1]

Early life and career

Thami was born in 1879 in the Imezouaren family, in the Ait Telouet tribe, a clan of the Southern Glaoua.[2] His family was originally in a place called Tigemmi n'Imezouaren in the Fatwaka tribe, near the Tassaout river.[3] His father was the qaid of Telouet, Mohammed ben Hammou, known as Tibibit,[4] and his mother was Zouhra Oum El Khaïr, a black slave.[5] When Si Mohammed died on 4 August 1886, his eldest son Si Mhamed took over his father's position and then died the same year.[2] After the death of Si M'hammed, his brother Si Madani took power[5] and put his brother T'hami as his khalifat (assistant).[6]

In the autumn of 1893, Sultan Moulay Hassan and his army were crossing the High Atlas mountains after a tax-gathering expedition when they were caught in a blizzard. They were rescued by Si Madani, and the grateful Sultan bestowed on Si Madani qaidats from Tafilalt to the Sous. In addition, he presented the Glaoua arsenal with a working 77-mm Krupp cannon, the only such weapon in Morocco outside the imperial army. The Glaoua army used this weapon to subdue rival warlords.[7]

In 1902, Madani, T'hami and the Glaoua force joined the imperial army of Moulay Abdelaziz as it marched against the pretender Bou Hamara. The Sultan's forces were routed by the pretender. Madani became a scapegoat, and spent months of humiliation at court before being allowed to return home. He thereupon began to actively work to depose Moulay Abdelaziz. This was achieved in 1907 with the enthronement of Abdelhafid of Morocco, who rewarded the Glaoua by appointing Si Madani as his Grand Vizier, and T'hami as Pasha of Marrakesh.[7]

French influence

The ruinous reigns of Moulay Abdelaziz and Moulay Hafid bankrupted Morocco and led first to riots, then to armed intervention by the French to protect their citizens and financial interests. As the situation worsened, a scapegoat once again had to be found, and again it was the Glaoua. Moulay Hafid accused Madani of keeping back tax money, and in 1911 stripped all Glaoua family members of their positions.[7]

In 1912 the Sultan was forced to sign the Treaty of Fez, which gave the French immense control over the Sultan, his pashas and qaids. Later that year, the pretender El Hiba entered Marrakesh with his army and demanded of the new Pasha, Driss Mennou (who had replaced T'hami), that he hand over all foreign Christians as hostages. These had sought refuge with the former Pasha, T'hami, who had tried previously but failed to get them out of the district. T'hami handed over the hostages, except for a sergeant whom he hid and supplied with a line of communication with the approaching French army. The French scattered El Hiba's warriors, and Driss Mennou ordered his men to overpower El Hiba's guards and liberate the hostages. These then went to T'hami's place to collect their belongings, and were found there by the French army in circumstances which suggested T'hami alone had saved them. T'hami was restored to his position as Pasha on the spot.[7] Seeing that the French were now the only effective power, T'hami aligned himself with them.

Lord of the Atlas

Madani died in 1918. The French immediately repaid T'hami's support by appointing him the head of the family ahead of Madani's sons. Only Si Hammou, Madani's son-in-law, managed to remain in his position as qaid of the Glawa (Aglaw in Tashelhit), based in Telouet (and therefore in charge of its arsenal). Not until Hammou died in 1934 did T'hami get full control of his legacy.[7]

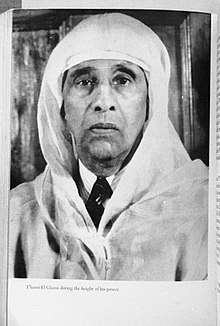

From that time on, T'hami's wealth and influence grew. His position as Pasha enabled him to acquire great wealth by means which were often dubious,[7] with interests in agriculture and mineral resources. His personal style and charm, as well as his prodigality with his wealth, made him many friends among the international fashionable set of the day. He visited the European capitals often, while his visitors at Marrakesh included Winston Churchill, Colette, Maurice Ravel, Charlie Chaplin.[8]

The Pasha attended the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II as a private guest of Winston Churchill, the two had met during the latter's trips to Marrakech, often to paint. The Pasha's lavish gifts of a jeweled crown and an ornate dagger were refused as it was not customary for gifts to be received from individuals not representing a government.[7]

According to his son Abdessadeq, one of the principal means by which he acquired great landholdings was that he was able to buy land at cheap prices during times of drought. During one such drought, he constructed an irrigated private golf course at Marrakesh at which Churchill often played. When the French protested about the waste of water, they were easily silenced by granting playing rights to the top officials.[8]

T'hami had two wives: Lalla Zineb, mother of his sons Hassan and Abdessadeq and widow of his brother Si Madani; and Lalla Fadna, by whom he had a son, Mehdi, and a daughter, Khaddouj. Mehdi was killed fighting in the French forces at the Battle of Monte Cassino. T'hami also had a number of concubines, of whom he had children by three: Lalla Kamar (sons Brahim, Abdellah, Ahmed and Madani), Lalla Nadida (son Mohammed and daughter Fattouma) and Lalla Zoubida (daughter Saadia). The first two of these had originally entered T'hami's harem as musicians imported from Turkey.[8]

Collaboration with the French

Opposition to the nationalists

As part of the resistance against the French occupation, a political party, the Istiqlal had started up with a nationalist (i.e. anti-colonialist) policy. T'hami and his son Brahim were supporters of the French, but several of T'hami's other sons were nationalists.[8] This could be risky; he had one of them imprisoned in a dungeon.[7]

T'hami had grown up and lived most of his life as a feudal warlord, and so had many of the other pashas and qaids. Their opposition to the nationalists was based on conservatism:[8]

- The only line of communication between the people and the Sultan was by means of the pashas and qaids; this was the route by which tax money found its way to the Makhzen. No-one - certainly not the nationalists, who were mostly commoners - should breach this protocol. The pashas and qaids believed that this social order was to the benefit of their subjects as well as themselves. This was perhaps true to this extent: any pasha or qaid expressing a nationalist sympathy was likely to be stripped of his position by the French and replaced by either a puppet or even a French official to the detriment of their subjects.

- As well as challenging traditional political power, the nationalists were also held to be responsible for endangering the spiritual leadership. Traditional religious sensibilities amongst the pashas and qaids were outraged by media pictures of royal princesses in bathing suits at the beach or by the pool. The nationalists were held to blame for introducing the Sultan to such new-fangled anti-Islamic ideas.

Thami was not opposed to nationalism (in the sense of being against French colonialism) in itself, but was offended that it seemed to be associated with an upset of the established temporal and spiritual authority of the Sultan.

Rupture with the sultan

Two incidents led up to the rupture of relations between T'hami and Sultan Mohammed V.[8]

- Mesfioua incident: On 18 November 1950 nationalists staged a demonstration at a tomb in the ruins of Aghmat. This was brutally suppressed by police acting on the orders of the local qaid of the Mesfioua tribe. The Sultan, on hearing of this, commanded the qaid to appear before him to explain himself. This order would normally have gone to the qaid's superior, T'hami, but he was in Paris and it went instead to his deputy, his son Brahim. Brahim, instead of obeying, decided to consult his father, but omitted to obtain a definite response. The end result was that the Sultan's order was not carried out, and the Sultan gained the impression that the Glaoui family had deliberately ignored it.

- Laghzaoui incident: the French had set up a Council of the Throne supposedly to advise the Sultan, but in reality to impose policy upon him. At a meeting of the Council on 6 December 1950, Mohammed Laghzaoui, a nationalist, was expelled by the person who effectively controlled the Council, the French Resident. The other nationalist members left with him, and were immediately received in private audience with the Sultan. This confirmed to T'hami that the nationalists and the Sultan were breaching established protocols of communication.

At the annual Feast of Mouloud it was customary for the Sultan's subjects to renew their vows of loyalty to him. This was done in private audiences with the pashas and qaids, and by a public demonstration by their assembled tribe.

T'hami's audience took place on 23 December 1950. Prior to this, Moulay Larbi El Alaoui, a member of the Makhzen had reportedly primed the Sultan to expect trouble from T'hami.[7] The Sultan let it be known that he expected the audience to conform to the traditional pledges of loyalty with no political content. T'hami, however, started off by blaming the Mesfioua and Laghzaoui incidents on the nationalists. When the Sultan calmly responded that he considered the nationalists to be loyal Moroccans, T'hami exploded into a diatribe to which the Sultan could only sit speechless, judging it was better not to provoke a man who clearly had lost control of his passions.[8] After T'hami exhausted himself, the Sultan continued his silence so T'hami left the palace. The Sultan then conferred with his Grand Vizier and Moulay Larbi and gave orders that T'hami was barred from appearing before him until further notice. After the Grand Vizier left to recall T'hami to receive this order, the next two qaids were admitted for their audience. As it happened these were Brahim and Mohammed, T'hami's sons, who were qaids in their own right. Brahim attempted to smooth things over by saying that T'hami had only spoken as a father might to his son. Suggesting that this was an acceptable way for a subject to speak to a king was in itself a breach of protocol which only made matters worse.[8] When T'hami arrived back at the palace, the Grand Vizier told him that both he and his family were no longer welcome. T'hami then sent his assembled tribespeoples and subordinate qaids' home without waiting for the customary public demonstration of loyalty; this action was construed by the palace as open mutiny.[8]

Coup d'état

T'hami regarded the Sultan's order as a personal insult that must be wiped out at all costs.[8] In addition, the Makhzen was dominated by Fassis (those from the city of Fez), and there was a traditional mutual distrust between the Fassis and those from Marrakesh. In T'hami's memory was the humiliation of himself and his brother Si Madani at the hands of a Fassi-dominated Makhzen during the reigns of Moulay Abdelaziz and Moulay Hafid.[8]

From that moment on he conspired with Abd El Hay Kittani and the French to replace Mohammed V with a new sultan, an elderly member of the royal family named Ben Arafa. On 17 August 1953, Kittani and the Glaoui unilaterally declared Ben Arafa to be the country's imām. On 25 August 1953, the French Resident had the Sultan and his family forcibly seized and deported to exile, and Ben Arafa was proclaimed the new sultan.[7]

Popular uprising against the coup

T'hami had already participated in one dethronement of a sultan in 1907, which had been met with popular indifference. With this "ossified" memory, he never expected another dethronement would lead to an insurrection. The great mistake made by T'hami and his associated pashas and qaids, according to his son Abdessadeq, was that unlike Mohammed V they simply failed to realise that by 1950 Moroccan society had evolved to the stage where feudal government was no longer acceptable to their subjects.[8]

A popular uprising began, directed mainly against the French but also against their Moroccan supporters. French citizens were massacred, the French forces responded with equal brutality, and French colonists began a campaign of terrorism against anyone (Moroccan or French) who expressed nationalist sympathies. T'hami was the target of a grenade attack, which did not however injure him. His chamberlain Haj Idder (formerly a slave of Si Madani) was injured in another such attack, and on recovery came to oppose the French.[8] Finally, an all-out war began in the Rif.

Rallying to the sultan

T'hami was at first totally prepared to support the French, machine gun in hand if necessary.[7] He was shaken, however, by the political "reforms" which the French began to demand to consolidate their hold on power, which would have had the same outcome as what he had feared from the nationalists: the eventual removal of the pashas and qaids.[8]

The French government, unnerved by way the country was rapidly becoming ungovernable, slowly began to think about how it might undo what had happened. T'hami detected this and equally slowly became as receptive to his nationalist son Abdessadeq as he had formerly been to his pro-French son Brahim. Ben Arafa abdicated on 1 August 1955. The French brought Mohammed V to France from exile, but also created a "Council of the Throne" as a caretaker government.

T'hami now no longer believed in anything the French said, and pointedly refused them support to suppress a student strike. By 17 October, T'hami had decided to notify the French and their Council that he supported the restoration of Mohammed V as Sultan. This notification was never sent, apparently because Brahim became aware of his intention and began his own negotiations with French interests. T'hami was shocked into a sudden suspicion that Brahim may have been planning to supersede him.[8]

To forestall this, Abdessadeq arranged a meeting between his father and leading nationalists, which took place over dinner on 25 October. At this meeting an announcement was drawn up in which T'hami recognized Mohammed V as rightful Sultan.[8] The next day, as soon as T'hami had addressed the Council of the Throne, the announcement was read out by Abdessadeq to a waiting crowd and simultaneously released to the media by nationalists in Cairo. The whole of Morocco was now united in the demand for the Sultan's restoration, and the French had no choice but to capitulate.

T'hami flew to France and on 8 November 1955 knelt in submission before Mohammed V, who forgave him his past mistakes.

Personal fortune

El Glaoui was one of the world's richest men following Pacha Boujemaa Mesfioui of Beni Mellal. He took a tithe of the almond, saffron and olive harvests in his vast domain, owned huge blocks of stock in French-run mines and factories, and received a rebate on machinery and automobiles imported into his realm. El Glaoui's fortune was somewhere in the neighborhood of $50 million at the time, more than $880 million, adjusted for inflation. [9]

Epilogue

El Glaoui died during his night prayers on 23 January 1956, not long after the return of the Sultan. His properties and wealth were later seized by the state.[10]

Hassan El Glaoui, another son of T'hami, is one of the best-known Moroccan figurative painters, with works selling for more than hundred of thousands pounds at Sotheby's. [11]

Abdessadeq El Glaoui, the son of Thami El Glaoui, and a past Moroccan ambassador to the USA, has written a book about his father and his relations with the French and the monarchy.[8][12]

Touria El Glaoui, the granddaughter of Thami El Glaoui, daughter of Hassan El Glaoui, is the founder of the 1:54 African art Fair. [13]

Mehdi El Glaoui, the grandson of Thami El Glaoui, son of Brahim El Glaoui, famous for his role as Sébastien in the television series Belle et Sébastien

Brice Bexter, great-grandson of Thami El Glaoui, grandson of Hassan El Glaoui, is a rising Moroccan and international actor.[14]

Honours

- Grand Cross of the Légion d'honneur (1925)

- Grand Officer of the Légion d'honneur (1919)

- Commandeur of the Légion d'honneur (1913)

- Officier of the Légion d'honneur (1912)

- Chevalier of the Légion d'honneur (1912)

- Croix de Guerre 1914–1918 with two palms (1916 at Sektana and 1917 at Tiznit)

Notes

- Ikeda, Ryo (December 2007). "The Paradox of Independence: The Maintenance of Influence and the French Decision to Transfer Power in Morocco". The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. 35 (4): 569–592. doi:10.1080/03086530701667526.

Perhaps el-Glaoui realised that his die-hard opposition to the ex-Sultan was no longer supported by the dignitaries and was merely contributing to the country's divisions. Thus he succumbed to the nationalist pressure, although not fully. Realising that the traditionalist dignitaries' strength was declining because of the rise of nationalism and feeling abandoned by France, el-Glaoui accepted the return of the ex-Sultan, who himself was at the apex of the traditional Muslim hierarchy, aiming to limit any further reduction of traditionalist force.

- Lahnite 2011, p. 81.

- Lahnite 2011, p. 79.

- Lahnite 2011, p. 81-82.

- Lahnite 2011, p. 82.

- Lahnite 2011, p. 84.

- Source: G. Maxwell, see References below

- Source: Abdessadeq El Glaoui, see References below.

- "MOROCCO: Who Is Boss?". May 20, 1957. Retrieved August 27, 2019 – via content.time.com.

- "telquel-online.com". www.telquel-online.com. Retrieved August 27, 2019.

- https://amp.ft.com/content/bb13a174-55fd-11e9-8b71-f5b0066105fe

- Interview (in French) with Abdessadeq El Glaoui in Hebdo Press (2004) Maroc Hebdo

- https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/01/arts/touria-el-glaoui-african-art-frieze.amp.html

- https://variety.com/2020/film/news/andy-garcia-action-drama-redemption-day-1203486366/

References

- Lords of the Atlas, by Gavin Maxwell (ISBN 0-907871-14-3). This is the classic work on El Glaoui in any language, by a best-selling author.

- Le Ralliement. Le Glaoui mon Père, by Abdessadeq El Glaoui (published 2004 in Morocco only, Ed. Marsam, Rabat, 391p.) (ISBN 9981-149-79-9). Gives a unique insight into family politics.

- Lahnite, Abraham (2011). La politique berbère du protectorat français au Maroc, 1912-1956 (in French). L'application du Traité de Fez dans la région de Souss Tome 3. Harmattan. ISBN 978-2-296-54982-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

![]()

- The palace of El Glaoui in Ouarzazate

- History as narrative

- Hassan El Glaoui the painter

- BBC article on the Kasbah of Telouet

- British Pathé footage of El Glaoui's funeral