Evenks

The Evenks (also spelled Ewenki or Evenki based on their endonym Ewenkī(l) )[note 1] are a Tungusic people of Northern Asia. In Russia, the Evenks are recognised as one of the indigenous peoples of the Russian North, with a population of 38,396 (2010 census). In China, the Evenki form one of the 56 ethnic groups officially recognised by the People's Republic of China, with a population of 30,875 (2010 census).[2] There are 537 Evenks in Mongolia (2015 census) called Khamnigan in Mongolian language.[3]

Эвэнкил | |

|---|---|

| |

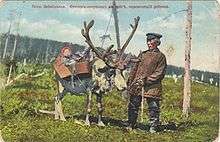

An Evenk family in the early 1900s | |

| Total population | |

| 69,856[1][2][3][4] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 38,396[1] | |

| 30,875[2] | |

| 537[3] | |

| 48[4] | |

| Languages | |

| Evenki, Russian, Chinese, Mongolian | |

| Religion | |

| Shamanism, Eastern Orthodox Christianity, Tibetan Buddhism[5][6][7] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Evens, Manchus, Oroqens, Oroch | |

Origin

The Evenks or Ewenki are sometimes conjectured to be connected to the Shiwei people who inhabited the Greater Khingan Range in the 5th to 9th centuries, although the native land of the majority of Evenki people is in the vast regions of Siberia between Lake Baikal and the Amur River. The Ewenki language forms the northern branch of the Manchu-Tungusic language group and is closely related to Even and Negidal in Siberia. By 1600 the Evenks or Ewenki of the Lena and Yenisey river valleys were successful reindeer herders. By contrast the Solons (ancestors of the Evenkis in China) and the Khamnigans (Ewenkis of Transbaikalia) had picked up horse breeding and the Mongolian deel from the Mongols. The Solons nomadized along the Amur River. They were closely related to the Daur people. To the west the Khamnigan were another group of horse-breeding Evenks in the Transbaikalia area. Also in the Amur valley a body of Siberian Evenki-speaking people were called Orochen by the Manchus.

Historical distribution

The ancestors of the south-eastern Evenks have most likely been in the Baikal region of Southern Siberia (near the modern-day Mongolian border) since the Neolithic era.

Considering the north-western Evenks Vasilevich claims: "The origin of the Evenks is the result of complex processes, different in time, involving the mixing of different ancient aboriginal tribes from the north of Siberia with tribes related in language to the Turks and Mongols. The language of these tribes took precedence over the languages of the aboriginal population". Elements of more modern Evenk culture, including conical tent dwellings, bone fish-lures, and birch-bark boats, were all present in sites that are believed to be Neolithic. From Lake Baikal, “they spread to the Amur and Okhotsk Sea…the Lena Basin…and the Yenisey Basin”.[8]

Contact with Russians

In the 17th century, the Russian empire made contact with the Evenks. Cossacks, who served as a kind of “border-guard” for the tsarist government, imposed a fur tax on the Siberian tribes. The Cossacks exploited the Evenk clan hierarchy and took hostages from the highest members in order to ensure payment of the tax. Although there was some rebellion against local officials, the Evenks generally recognized the need for peaceful cultural relations with the Russians (Vasilevich, 624). Contact with the Russians and constant demand for fur taxes pushed the Evenks east all the way to Sakhalin island, where some still live today (Cassells). In the 19th century some groups migrated south and east into Mongolia and Manchuria (Vasilevich, 625). Today there are still Evenk populations in Sakhalin, Mongolia, and Manchuria (Ethnologue), and to a lesser extent, their traditional Baikal region (Janhunen). Russian invasion of the Evenks (and other indigenous peoples) resulted in language erosion, traditional decline, identity loss, among others, of thereof. This was especially the case during the Soviet regime. Soviet policies of collectivization, forced sedentarization (or sometimes refer to as Sedentism), "unpromising villages", and Russification of the education system compromised social, cultural, and mental well-being of the Evenks.[9][10] Today, few people can speak the Evenki language, reindeer herding is in significant decline, the suicide rate is extremely high, and alcoholism is a serious issue.

Traditional life

Traditionally they were a mixture of pastoralists and hunter-gatherers—they relied on their domesticated reindeer for milk and transport and hunted other large game for meat (Vasilevich, 620-1). Today “[t]he Evenks are divided into two large groups…engaging in different types of economy. These are the hunting and reindeer-breeding Evenks…and the horse and cattle pastoral Evenks as well as some farming Evenks” (620). The Evenks lived mostly in areas of what is called a taiga, or boreal forest. They lived in conical tents made from birch bark or reindeer skin tied to birch poles. When they moved camp, the Evenks would leave these frameworks and carry only the more portable coverings. During winter, the hunting season, most camps consisted of one or two tents while the spring encampments had up to 10 households (Vasilevich, 637).

Their skill of riding the domesticated reindeer allowed the Evenks to “colonize vast areas of the eastern taiga which had previously been impenetrable” (Vitebsky, 31). The Evenks used a saddle unique to their culture which is placed on the shoulders of the reindeer so as to lessen the strain on the animal, and used not stirrups but a stick to balance (31-32). Evenks did not develop reindeer sledges until comparatively recent times (32). They instead used their reindeer as pack animals and often traversed great distances on foot, using snowshoes or skis (Vasilevich, 627). The Evenki people did not eat their domesticated reindeer (although they did hunt and eat wild reindeer) but kept them for milk. (Forsyth, 49-50).

Large herds of reindeer were very uncommon. Most Evenks had around 25 head of reindeer because they were generally bred for transportation. Unlike in several other neighboring tribes Evenk reindeer-breeding did not include “herding of reindeer by dogs nor any other specific features” (Vasilevich, 629). Very early in the spring season, the winter camps broke up and moved to places suitable for calving. Several households pastured their animals together throughout the summer, being careful to keep “[s]pecial areas…fenced off…to guard the newborn calves against being trampled on in a large herd” (629).

Clothing

The Evenks wore a characteristic garb “adapted to the cold but rather dry climate of Central Siberia and to a life of mobility…they wore brief garments of soft reindeer or elk skin around their hips, along with leggings and moccasins, or else long supple boots reaching to the thigh” (49). They also wore a deerskin coat that did not close in front but was instead covered with an apron-like cloth. Some Evenkis decorated their clothing with fringes or embroidery (50). The Evenki traditional costume always consisted of these elements: the loincloth made of animal hide, leggings, and boots of varying lengths (Vasilevich, 641). Facial tattooing was also very common.

Hunting

The traditional Evenk economy was a mix of pastoralism (of horses or reindeer), fishing, and hunting. The Evenk who lived near the Okhotsk Sea hunted seal, but for most of the taiga-dwellers, elk, wild reindeer, and fowl were the most important game animals. Other animals included “roe deer, bear, wolverine, lynx, wolf, Siberian marmot, fox, and sable” (Vasilevich, 626). Trapping did not become important until the imposition of the fur tax by the tsarist government. Before acquiring guns in the 18th century, Evenks used steel bows and arrows. Along with their main hunting implements, hunters always carried a “pike”—“which was a large knife on a long handle used instead of an axe when passing through the thick taiga or as a spear when hunting bear” (626). The Evenks have deep respect for animals and all elements of nature: "It is forbidden to torment an animal, bird, or insect, and a wounded animal must be finished off immediately. It is forbidden to spill the blood of a killed animal or defile it. It is forbidden to kill animals or birds that were saved from pursuit by predators or came to a person for help in a natural disaster." (Sirina, 24).

Evenks of Russia

The Evenks were formerly known as tungus. This designation was spread by the Russians, who acquired it from the Yakuts and the Siberian Tatars (in the Yakut language tongus) in the 17th century. The Evenks have several self-designations, of which the best known is evenk. This became the official designation for the people in 1931. Some groups call themselves orochen ('an inhabitant of the River Oro'), orochon ('a rearer of reindeer'), ile ('a human being'), etc. At one time or another tribal designations and place names have also been used as self-designations, for instance manjagir, birachen, solon, etc. Several of these have even been taken for separate ethnic entities.

There is also a similarly named Siberian group called the Evens (formerly known as Lamuts). Although related to the Evenks, the Evens are now considered to be a separate ethnic group.

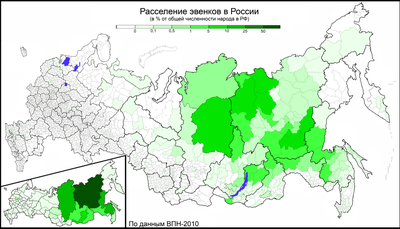

The Evenks are spread over a huge territory of the Siberian taiga from the River Ob in the west to the Okhotsk Sea in the east, and from the Arctic Ocean in the north to Manchuria and Sakhalin in the south. The total area of their habitat is about 2,500,000 km². In all of Russia only the Russians inhabit a larger territory. According to the administrative structure, the Evenks live, from west to east, in Tyumen and Tomsk Oblasts, Krasnoyarsk Krai with Evenk Autonomous Okrug, Irkutsk, Chita, and Amur Oblasts, the Buryat and the Sakha Republics, Khabarovsk Krai, and Sakhalin Oblast. However, the territory where they are a titular nation is confined solely to Evenk Autonomous Okrug, where 3,802 of the 35,527 Evenks live (according to the 2002 Census). More than 18,200 Evenks live in the Sakha Republic.

Evenki is the largest of the northern group of the Manchu-Tungus languages, a group which also includes Even and Negidal.

Many Evenks in Russia still engage in a traditional lifestyle of raising reindeer, fishing, and hunting.[11]

Russian Federation

According to the 2002 census 35,527 Evenki lived in Russia.

| Administrative unit | Evenki population, according to the 2002 census |

|---|---|

| Sakha (Yakutia) Republic | 18,232 |

| Krasnoyarsk Krai | 4,632 |

| Evenk Autonomous Okrug (Evenkia) | 3,802 |

| Khabarovsk Krai | 4,533 |

| Amur Oblast | 1,501 |

| Sakhalin Oblast | 243 |

| Republic of Buryatia | 2,334 |

| Irkutsk Oblast | 1,431 |

| Zabaykalsky Krai | 1,492 |

| Tomsk Oblast | 103 |

| Tyumen Oblast | 109 |

Evenks of China

According to the 2000 Census, there are 30,505 Evenks in China mainly made up of the Solons and the Khamnigans. 88.8% of China's Evenks live in the Hulunbuir region in the north of the Inner Mongolia Province, near the city of Hailar. The Evenk Autonomous Banner is also located near Hulunbuir. There are also around 3,000 Evenks in neighbouring Heilongjiang Province.

The Manchu Emperor Hong Taiji conquered the Evenks in 1640, and executed their leader Bombogor. After the Manchu conquest, the Evenks were incorporated into the Eight Banners.

In 1763, the Qing government moved 500 Solon Evenk and 500 Daur families to the Tacheng and Ghulja areas of Xinjiang, in order to strengthen the empire's western border. 1020 Xibe families (some 4000 persons) followed the next year. Since then, however, the Solons of Xinjiang have assimilated into other ethnic groups, and are not identified as such anymore.[12][13]

Some Evenkis fled to Soviet Siberia across the Amur river after murdering a Japanese officer to avoid punishment from the Japanese. The Japanese occupation led to many murders of Evenkis and Evenki men were conscripted as scouts and rangers by the Japanese secret service in 1942.[14]

The Evenks of China today tend to be settled pastoralists and farmers.[11]

By county

- County-level distribution of the Evenk

(Only includes counties or county-equivalents containing >0.1% of China's Evenk population.)

Evenks of Ukraine

According to the 2001 census, there were 48 Evenks living in Ukraine. The majority (35) stated that their native language was Russian; four indicated Evenk as their native language, and three that it was Ukrainian.[15]

Religion

Prior to contact with the Russians, the belief system of the Evenks was animistic. Many have adopted Tibetan Buddhism.[5][6][7]

The Evenki, like most nomadic, pastoral, and subsistence agrarian peoples, spend most of their lives in very close contact with nature. Because of this, they develop what A. A. Sirina calls an "ecological ethic". By this she means "a system of responsibility of people to nature and her spirit masters, and of nature to people"(9). Sirina interviewed many Evenks who until very recently spent much of their time as reindeer herders in the taiga, just like their ancestors. The Evenki people also spoke along the same lines: their respect for nature and their belief that nature is a living being.

This idea, "[t]he embodiment, animation, and personification of nature—what is still called the animistic worldview—is the key component of the traditional worldview of hunter-gatherers" (Sirina, 13). Although most of the Evenkis have been "sedentarized"—that is, made to live in settled communities instead of following their traditional nomadic way of life (Fondahl, 5)—"[m]any scholars think that the worldview characteristic of hunter-gatherer societies is preserved, even if they make the transition to new economic models (Sirina, 30, quoting Barnard 1998, Lee 1999, Peterson 1999).

Although nominally Christianized in the 18th century, the Evenki people maintain many of their historical beliefs—especially shamanism (Vasilevich, 624). The Christian traditions were "confined to the formal performance of Orthodox rites which were usually timed for the arrival of the priest in the taiga" (647).

The religious beliefs and practices of the Evenks are of great historical interest since these retain some archaic forms of belief. Among the most ancient ideas are spiritualization and personification of all natural phenomena, belief in an upper, middle, and lower world, belief in the soul (omi) and certain totemistic concepts. There were also various magical rituals associated with hunting and guarding herds. Later on, these rituals were conducted by shamans. Shamanism brought about the development of the views of spirit-masters (Vasilevich 647).

There are few sources on the shamanism of the Evenki peoples below the Amur/Helongkiang river in Northern China. There is a brief report of fieldwork conducted by Richard Noll and Kun Shi in 1994 of the life of the shamaness Dula'r (Evenki name), also known as Ao Yun Hua (her Han Chinese name).[16] She was born in 1920 and was living in the village of Yiming Gatsa in the Evenki Banner (county) of the Hulunbuir Prefecture, in the Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region. While not a particularly good informant, she described her initiatory illness, her multiyear apprenticeship with a Mongol shaman before being allowed to heal at the age of 25 or 26, and the torments she experienced during the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s when most of her shamanic paraphernalia was destroyed. Mongol and Buddhist Lamaist influences on her indigenous practice of shamansim were evident. She hid her prize possession—an Abagaldi (bear spirit) shaman mask, which has also been documented among the Mongols and Dauer peoples in the region. The field report and color photographs of this shaman are available online.[17]

Olga Kudrina (c. 1890–1944) was a shaman among the Reindeer Evenki of northern Inner Mongolia along the Amur River's Great Bend (today under the jurisdiction of Genhe, Hulunbuir).[18]

Notable Evenks

- Bombogor (d. 1640), leader of Evenk federation

- Olga Kudrina (c. 1890–1944), shaman

- Semyon Nomokonov (1900–1973), sniper during World War II

- Nikita Sakharov (1915–1945), poet, prose writer

- Alitet Nemtushkin (1939–2006), poet

- Maria Fedotova-Nulgynet (b. 1946), poet, children's writer, storyteller

- Galina Varlamova (b. 1951), writer, philologist, folklorist

- Ureltu (b. 1952), writer

- D. O. Chaoke (b. 1958), linguist

See also

- Hamnigan - (Hamnigan Mongols)

Bibliography

- D. O. Chaoke (an Evenk), WANG Lizhen (2002). 鄂温克族宗教信仰与文化 (Zipped NLC (Modified JBIG)). Beijing: Minzu University of China. ISBN 978-7-81056-700-8.

- (The online edition needs a Book Reader for NLC and a ZIP extractor)

- "Altaic." Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia. 6th ed. 2009. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. Web. 4 Nov. 2009.

- Anderson, David G. "Is Siberian Reindeer Herding in Crisis? Living with Reindeer Fifteen Yearss after the End of State Socialism." Nomadic Peoples NS 10.2 (2006): 87-103. EBSCO. Web. 6 Nov. 2009.

- Bulatova, Nadezhda, and Lenore Grenoble. Evenki. Munchen: LINCOM Europa, 1999. Print. Languages of the World.

- "Evenki." Cassell's Peoples, Nations, and Cultures. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2005. EBSCO. Web. 4 Nov. 2009.

- "Evenki." Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth Edition. Ed. Paul M. Lewis. SIL International, 2009. Web. 8 Dec. 2009.[19]

- Fondahl, Gail. Gaining ground? Evenkis, land and reform in southeastern Siberia. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1998. Print.

- Forsyth, James. History of the Peoples of Siberia: Russia's North Asian Colony, 1581-1990. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1992. Print.

- Georg, Stefan, Peter A. Michalove, Alexis M. Ramer, and Paul J. Sidwell. "Telling general linguists about Altaic." Journal of Linguistics 35.1 (1999): 65-98. JSTOR. Web. 8 Dec. 2009.

- Hallen, Cynthia L. "A Brief Exploration of the Altaic Hypothesis." Department of Linguistics. Brigham Young University, 6 Sept. 1999. Web. 8 Dec. 2009.[20]

- Janhunen, Juha. "Evenki." Interactive Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger. Ed. Christopher Moseley. UNESCO Culture Sector, 31 Mar. 2009. Web. 8 Dec. 2009.[21]

- Nedjalkov, Igor. Evenki. London: Routledge, 1997. Print. Descriptive Grammars.

- Sirina, Anna A. Katanga Evenkis in the 20th Century and the Ordering of their Life-world, transl. from 2nd Russian edn (2002), Northern Hunter-Gatherers Research Series 2, Edmonton: CCI Press and Baikal Archaeology Project, 2006.

- Sirina, Anna A. "People Who Feel the Land: The Ecological Ethic of the Evenki and Eveny." Trans. James E. Walker. Anthropology & Archaeology of Eurasia 3rd ser. 47.Winter 2008-9 (2009): 9-37. EBSCOHost. Web. 27 November 2009.

- Turov, Mikhail G. Evenki Economy in the Central Siberian Taiga at the Turn of the 20th Century: Principles of Land Use, transl. from 2nd Russian edn (1990), Northern Hunter-Gatherers Research Series 5, Edmonton: CCI Press and the Baikal Archaeology Project, 2010.

- Vasilevich, G. M., and A. V. Smolyak. "Evenki." The Peoples of Siberia. Ed. Stephen Dunn. Trans. Scripta Technica, Inc. Chicago: The University of Chicago, 1964. 620-54. Print.

- Vitebsky, Piers. Reindeer people: Living with Animals and Spirits in Siberia. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2005. Print.

- Wood, Alan, and R. A. French, eds. Development of Siberia: People and Resources. New York: St. Martin's, 1989. Print.

The Evenki in literature

- Chi, Zijian (2013). 《额尔古纳河右岸》 [The Last Quarter of the Moon]. Translated by Humes, Bruce. Harvill Secker..[22]

- The Moose of Ewenki 《鄂温克的驼鹿》, picture book written by Gerelchimeg Blackcrane (格日勒其木格·黑鹤), illustrated by Jiu Er (九儿), translated by Helen Mixter . (Greystone Kids, 2019)[23]

Notes

References

- Ethnic groups in Russia, 2010 census, Rosstat. Retrieved 15 February 2012 (in Russian)

- "Evenk Archives - Intercontinental Cry". Intercontinental Cry. Retrieved 2017-06-30.

- "2015 POPULATION AND HOUSING BY-CENSUS OF MONGOLIA: NATIONAL REPORT". National Statistics Office of Mongolia. 20 February 2017.

- "About number and composition population of Ukraine by data All-Ukrainian census of the population 2001". Ukraine Census 2001. State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. Archived from the original on 17 December 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- "Ewenki, Solon" (PDF). Asiaharvest.org. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- "Ewenki, Tungus" (PDF). Asiaharvest.org. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- Шубин А. Ц. Краткий очерк этнической истории эвенков Забайкалья (XVIII-XX век). Улан-Удэ: Бурят. кн. изд-во, 1973. С. 64, 65 (in Russian)

- Vasilevich (623)

- Klokov, K.B., Khrushchev, S.A. (2010). Demographic dynamics of the indigenous small-numbered peoples of the Russian North, 1897-2002. Sibirica, 9, 41-65

- Vakhtin, N. (1992). Native peoples of the Russian Far North. London

- Winston, Robert, ed. (2004). Human: The Definitive Visual Guide. New York: Dorling Kindersley. p. 428. ISBN 0-7566-0520-2.

- Herold J. Wiens "Change in the Ethnography and Land Use of the Ili Valley and Region, Chinese Turkestan", Annals of the Association of American Geographers, Vol. 59, No. 4 (Dec., 1969), pp. 753-775 (JSTOR access required)

- Tianshannet / Окно в Синьцзян / Народности, не относящиеся к тюркской группе Tianshannet Archived 2009-04-30 at the Wayback Machine (Window to Xinjiang / Non-Turkic peoples) (in Russian)

- Kolås, Åshild; Xie, Yuanyuan, eds. (2005). Reclaiming the Forest: The Ewenki Reindeer Herders of Aoluguya. Berghahn Books. p. 2. ISBN 1782386319.

- State statistics committee of Ukraine - National composition of population, 2001 census (Ukrainian)

- Richard Noll and Kun Shi, A Solon Evenki shaman and her Abgaldi Shaman mask. Shaman, 2007, 15 (1-2):167-174

- Noll, Richard. ""A Solon Ewenki shaman and her Abagaldai mask," Shaman (2007), 15 (1-2)". Academia.edu. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- Heyne, F. Georg (2007), "Notes on Blood Revenge among the Reindeer Evenki of Manchuria" (PDF), Asian Folklore Studies, 66 (1/2): 165–178

- "Evenki". Ethnologue.com. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- "A Brief Exploration of the Altaic Hypothesis". Linguistics.byu.edu. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- "UNESCO Culture Sector - Intangible Heritage - 2003 Convention : UNESCO Interactive Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger". 22 February 2009. Archived from the original on 2009-02-22. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- Humes, Bruce (2018-02-01). "Chi Zijian's "Last Quarter of the Moon": Guide to Related Links". Fei Piao - Transitioning from China to Africa. Retrieved 2019-08-28.

- anguche (2019-08-27). "85. The Moose of Ewenki". Chinese books for young readers. Retrieved 2019-08-28.