Democratic-Republican Party

The Democratic-Republican Party, better known at the time under various other names,[lower-alpha 1] was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the early 1790s that championed republicanism, political equality, and expansionism. The party became increasingly dominant after the 1800 elections as the opposing Federalist Party collapsed. The Democratic-Republicans later splintered during the 1824 presidential election. One faction of the Democratic-Republicans eventually coalesced into the modern Democratic Party, while the other faction ultimately formed the core of the Whig Party.

Democratic-Republican Party | |

|---|---|

| |

| Other name | Republican Party Jeffersonian Republicans Democratic Party[lower-alpha 1] |

| Leader | |

| Founded | 1792 |

| Dissolved | 1825 |

| Preceded by | Anti-Administration party |

| Succeeded by | |

| Ideology | |

| Political position | Center-left to left-wing[4][5] |

| Colors | |

| |

The Democratic-Republican Party originated as a faction in Congress that opposed the centralizing policies of Alexander Hamilton, who served as Secretary of the Treasury under President George Washington. The Democratic-Republicans and the opposing Federalist Party each became more cohesive during Washington's second term, partly as a result of the debate over the Jay Treaty. Though he was defeated by Federalist John Adams in the 1796 presidential election, Jefferson and his Democratic-Republican allies came into power following the 1800 elections. As president, Jefferson presided over a reduction in the national debt and government spending, and completed the Louisiana Purchase with France.

Madison succeeded Jefferson as president in 1809 and led the country during the largely inconclusive War of 1812 with Britain. After the war, Madison and his congressional allies established the Second Bank of the United States and implemented protective tariffs, marking a move away from the party's earlier emphasis on states' rights and a strict construction of the United States Constitution. The Federalists collapsed after 1815, beginning a period known as the Era of Good Feelings. Lacking an effective opposition, the Democratic-Republicans split into groups after the 1824 presidential election; one faction supported President John Quincy Adams, while the other faction backed General Andrew Jackson. Jackson's faction eventually coalesced into the Democratic Party, while supporters of Adams became known as the National Republican Party, which itself later merged into the Whig Party.

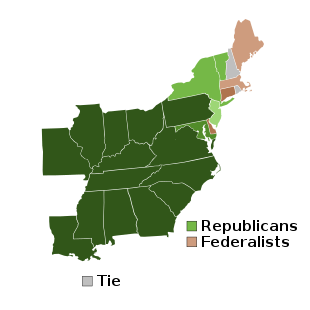

Democratic-Republicans were deeply committed to the principles of republicanism, which they feared were threatened by the supposed monarchical tendencies of the Federalists. During the 1790s, the party strongly opposed Federalist programs, including the national bank. After the War of 1812, Madison and many other party leaders came to accept the need for a national bank and federally funded infrastructure projects. In foreign affairs, the party advocated western expansion and tended to favor France over Britain, though the party's pro-French stance faded after Napoleon took power. The Democratic-Republicans were strongest in the South and the western frontier, and weakest in New England.

History

Founding, 1789–1796

In the 1788–89 presidential election, the first such election following the ratification of the United States Constitution in 1788, George Washington won the votes of every member of the Electoral College.[6] His unanimous victory in part reflected the fact that no formal political parties had formed at the national level in the United States prior to 1789, though the country had been broadly polarized between the Federalists, who supported ratification of the Constitution, and the Anti-Federalists, who opposed ratification.[7] Washington selected Thomas Jefferson as Secretary of State and Alexander Hamilton as Secretary of the Treasury,[8] and he relied on James Madison as a key adviser and ally in Congress.[9]

Hamilton implemented an expansive economic program, establishing the First Bank of the United States,[10] and convincing Congress to assume the debts of state governments.[11] Hamilton pursued his programs in the belief that they would foster a prosperous and stable country.[12] His policies engendered an opposition, chiefly concentrated in the Southern United States, that objected to Hamilton's anglophilia and accused him of unduly favoring well-connected wealthy Northern merchants and speculators. Madison emerged as the leader of the congressional opposition while Jefferson, who declined to publicly criticize Hamilton while both served in Washington's Cabinet, worked behind the scenes to stymie Hamilton's programs.[13] Jefferson and Madison established the National Gazette, a newspaper which recast national politics not as a battle between Federalists and Anti-Federalists, but as a debate between aristocrats and republicans.[14] In the 1792 election, Washington effectively ran unopposed for president, but Jefferson and Madison backed New York Governor George Clinton's unsuccessful attempt to unseat Vice President John Adams.[15]

Political leaders on both sides were reluctant to label their respective faction as a political party, but distinct and consistent voting blocs emerged in Congress by the end of 1793. Ultimately, Jefferson's followers became known as the Republicans (or the Democratic-Republicans)[16] and Hamilton's followers became known as the Federalists.[17] While economic policies were the original motivating factor in the growing partisan split, foreign policy also became a factor as Hamilton's followers soured on the French Revolution and Jefferson's allies continued to favor it.[18] In 1793, after Britain entered the French Revolutionary Wars, several Democratic-Republican Societies were formed in opposition to Hamilton's economic policies and in support of France.[19] Partisan tensions escalated as a result of the Whiskey Rebellion and Washington's subsequent denunciation of the Democratic-Republican Societies, a group of local political societies that favored democracy and generally supported the Democratic-Republican Party.[20] The ratification of the Jay Treaty further inflamed partisan warfare, resulting in a hardening of the divisions between the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans.[19]

By 1795–96, election campaigns—federal, state and local—were waged primarily along partisan lines between the two national parties, although local issues continued to affect elections, and party affiliations remained in flux.[21] As Washington declined to seek a third term, the 1796 presidential election became the first contested president election. Having retired from Washington's Cabinet in 1793, Jefferson had left the leadership of the Democratic-Republicans in Madison's hands. Nonetheless, the Democratic-Republican congressional nominating caucus chose Jefferson as the party's presidential nominee on the belief that he would be the party's strongest candidate; the caucus chose Senator Aaron Burr of New York as Jefferson's running mate.[22] Meanwhile, an informal caucus of Federalist leaders nominated a ticket of John Adams and Thomas Pinckney.[23] Though the candidates themselves largely stayed out of the fray, supporters of the candidates waged an active campaign; Federalists attacked Jefferson as a francophile and atheist, while the Democratic-Republicans accused Adams of being an anglophile and a monarchist.[24] Ultimately, Adams won the presidency by a narrow margin, garnering 71 electoral votes to 68 for Jefferson, who became the vice president.[23][lower-alpha 2]

Adams and the Revolution of 1800

Shortly after Adams took office, he dispatched a group of envoys to seek peaceful relations with France, which had begun attacking American shipping after the ratification of the Jay Treaty. The failure of talks, and the French demand for bribes in what became known as the XYZ Affair, outraged the American public and led to the Quasi-War, an undeclared naval war between France and the United States. The Federalist-controlled Congress passed measures to expand the army and navy and also pushed through the Alien and Sedition Acts. The Alien and Sedition Acts restricted speech that was critical of the government, while also implementing stricter naturalization requirements.[26] Numerous journalists and other individuals aligned with the Democratic-Republicans were prosecuted under the Sedition Act, sparking a backlash against the Federalists.[27] Meanwhile, Jefferson and Madison drafted the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, which held that state legislatures could determine the constitutionality of federal laws.[28]

In the 1800 presidential election, the Democratic-Republicans once again nominated a ticket of Jefferson and Burr. Shortly after a Federalist caucus re-nominated President Adams on a ticket with Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, Adams dismissed two Hamilton allies from his Cabinet, leading to an open break between the two key figures in the Federalist Party.[29] Though the Federalist Party united against Jefferson's candidacy and waged an effective campaign in many states, the Democratic-Republicans won the election by winning most Southern electoral votes and carrying the crucial state of New York.[30] Jefferson and Burr both finished with 73 electoral votes, more than Adams or Pinckney, necessitating a contingent election between Jefferson and Burr in the House of Representatives.[lower-alpha 2] Burr declined to take his name out of consideration, and the House deadlocked as most Democratic-Republican congressmen voted for Jefferson and most Federalists voted for Burr. Preferring Jefferson to Burr, Hamilton helped engineer Jefferson's election on the 36th ballot of the contingent election.[31] Jefferson would later describe the 1800 election, which also saw Democratic-Republicans gain control of Congress, as the "Revolution of 1800", writing that it was "as real of a revolution in the principles of our government as that of [1776] was in its form."[32] In the final months of his presidency, Adams reached an agreement with France to end the Quasi-War[33] and appointed several Federalist judges, including Chief Justice John Marshall.[34]

Jefferson's presidency, 1801–1809

Despite the intensity of the 1800 election, the transition of power from the Federalists to the Democratic-Republicans was peaceful.[35] In his inaugural address, Jefferson indicated that he would seek to reverse many Federalist policies, but he also emphasized reconciliation, noting that "every difference of opinion is not a difference of principle".[36] He appointed a geographically balanced and ideologically moderate Cabinet that included Madison as Secretary of State and Albert Gallatin as Secretary of the Treasury; Federalists were excluded from the Cabinet, but Jefferson appointed some prominent Federalists and allowed many other Federalists to keep their positions.[37] Gallatin persuaded Jefferson to retain the First Bank of the United States, a major part of the Hamiltonian program, but other Federalist policies were scrapped.[38] Jefferson and his Democratic-Republican allies eliminated the whiskey excise and other taxes,[39] shrank the army and the navy,[40] repealed the Alien and Sedition Acts, and pardoned all ten individuals who had been prosecuted under the acts.[41]

With the repeal of Federalist laws and programs, many Americans had little contact with the federal government in their daily lives, with the exception of the postal service.[42] Partly as a result of these spending cuts, Jefferson lowered the national debt from $83 million to $57 million between 1801 and 1809.[43] Though he was largely able to reverse Federalist policies, Federalists retained a bastion of power on the Supreme Court; Marshall Court rulings continued to reflect Federalist ideals until Chief Justice Marshall's death in the 1830s.[44] In the Supreme Court case of Marbury v. Madison, the Marshall Court established the power of judicial review, through which the judicial branch had the final word on the constitutionality of federal laws.[45]

By the time Jefferson took office, Americans had settled as far west as the Mississippi River.[46] Many in the United States, particularly those in the west, favored further territorial expansion, and especially hoped to annex the Spanish province of Louisiana.[47] In early 1803, Jefferson dispatched James Monroe to France to join ambassador Robert Livingston on a diplomatic mission to purchase New Orleans.[48] To the surprise of the American delegation, Napoleon offered to sell the entire territory of Louisiana for $15 million.[49] After Secretary of State James Madison gave his assurances that the purchase was well within even the strictest interpretation of the Constitution, the Senate quickly ratified the treaty, and the House immediately authorized funding.[50] The Louisiana Purchase nearly doubled the size of the United States, and Treasury Secretary Gallatin was forced to borrow from foreign banks to finance the payment to France.[51] Though the Louisiana Purchase was widely popular, some Federalists criticized it; Congressman Fisher Ames argued that "We are to spend money of which we have too little for land of which we already have too much."[52]

By 1804, Vice President Burr had thoroughly alienated Jefferson, and the Democratic-Republican presidential nominating caucus chose George Clinton as Jefferson's running mate for the 1804 presidential election. That same year, Burr challenged Hamilton to a duel after taking offense to a comment allegedly made by Hamilton; Hamilton died in the subsequent duel. Bolstered by a superior party organization, Jefferson won the 1804 election in a landslide over Federalist candidate Charles Cotesworth Pinckney.[53] In 1807, as the Napoleonic Wars continued, the British announced the Orders in Council, which called for a blockade on the French Empire.[54] In response to subsequent British and French attacks on American shipping, the Jefferson administration passed the Embargo Act of 1807, which cut off trade with Europe.[55] The embargo proved unpopular and difficult to enforce, especially in Federalist-leaning New England, and expired at the end of Jefferson's second term.[56] Jefferson declined to seek a third term in the 1808 presidential election, but helped Madison triumph over George Clinton and James Monroe at the party's congressional nominating caucus. Madison won the general election in a landslide over Pinckney.[57]

Madison's presidency, 1809–1817

As attacks on American shipping continued after Madison took office, both Madison and the broader American public moved towards war.[58] Popular anger towards Britain led to the election of a new generation of Democratic-Republican leaders, including Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun, who championed high tariffs, federally funded internal improvements, and a belligerent attitude towards Britain.[59] On June 1, 1812, Madison asked Congress for a declaration of war.[60] The declaration was passed largely along sectional and party lines, with intense opposition coming from the Federalists and some other congressmen from the Northeast.[61] For many who favored war, national honor was at stake; John Quincy Adams wrote that the only alternative to war was "the abandonment of our right as an independent nation."[62] George Clinton's nephew, DeWitt Clinton, challenged Madison in the 1812 presidential election. Though Clinton assembled a formidable coalition of Federalists and anti-Madison Democratic-Republicans, Madison won a close election.[63]

Madison initially hoped for a quick end to the War of 1812, but the war got off to a disastrous start.[64] The United States had more military success in 1813, and a force under William Henry Harrison crushed Native American and British resistance in the Old Northwest with a victory in the Battle of the Thames. The British shifted soldiers to North America in 1814 following the abdication of Napoleon, and a British detachment burned Washington in August 1814.[65] In early 1815, Madison learned that his negotiators in Europe had reached the Treaty of Ghent, ending the war without major concessions by either side.[66] Though it had no effect on the treaty, General Andrew Jackson's victory in the January 1815 Battle of New Orleans ended the war on a triumphant note.[67] Napoleon's defeat at the June 1815 Battle of Waterloo brought a final end to the Napoleonic Wars and attacks on American shipping.[68] With Americans celebrating a successful "second war of independence" from Britain, the Federalist Party slid towards national irrelevance.[69] The subsequent period of virtually one-party rule by the Democratic-Republican Party is known as the "Era of Good Feelings."

In his first term, Madison and his allies had largely hewed to Jefferson's domestic agenda of low taxes and a reduction of the national debt, and Congress allowed the national bank's charter to expire during Madison's first term.[70] The challenges of the War of 1812 led many Democratic-Republicans to reconsider the role of the federal government.[71] When the 14th Congress convened in December 1815, Madison proposed the re-establishment of the national bank, increased spending on the army and the navy, and a tariff designed to protect American goods from foreign competition. Madison's proposals were strongly criticized by strict constructionists like John Randolph, who argued that Madison's program "out-Hamiltons Alexander Hamilton."[72] Responding to Madison's proposals, the 14th Congress compiled one of the most productive legislative records up to that point in history, enacting the Tariff of 1816 and establishing the Second Bank of the United States.[73] At the party's 1816 congressional nominating caucus, Secretary of State James Monroe defeated Secretary of War William H. Crawford in a 65-to-54 vote.[74] The Federalists offered little opposition in the 1816 presidential election and Monroe won in a landslide election.[75]

Era of Good Feelings, 1817–1825

Monroe believed that the existence of political parties was harmful to the United States,[76] and he sought to usher in the end of the Federalist Party by avoiding divisive policies and welcoming ex-Federalists into the fold.[77] Monroe favored infrastructure projects to promote economic development and, despite some constitutional concerns, signed bills providing federal funding for the National Road and other projects.[78] Partly due to the mismanagement of national bank president William Jones, the country experienced a prolonged economic recession known as the Panic of 1819.[79] The panic engendered a widespread resentment of the national bank and a distrust of paper money that would influence national politics long after the recession ended.[80] Despite the ongoing economic troubles, the Federalists failed to field a serious challenger to Monroe in the 1820 presidential election, and Monroe won re-election essentially unopposed.[81]

During the proceedings over the admission of Missouri Territory as a state, Congressman James Tallmadge, Jr. of New York "tossed a bombshell into the Era of Good Feelings" by proposing amendments providing for the eventual exclusion of slavery from Missouri.[82] The amendments sparked the first major national slavery debate since the ratification of the Constitution,[83] and instantly exposed the sectional polarization over the issue of slavery.[84] Northern Democratic-Republicans formed a coalition across partisan lines with the remnants of the Federalist Party in support of the amendments, while Southern Democratic-Republicans were almost unanimously against such the restrictions.[85] In February 1820, Congressman Jesse B. Thomas of Illinois proposed a compromise, in which Missouri would be admitted as a slave state, but slavery would be excluded in the remaining territories north of the parallel 36°30′ north.[86] A bill based on Thomas's proposal became law in April 1820.[87]

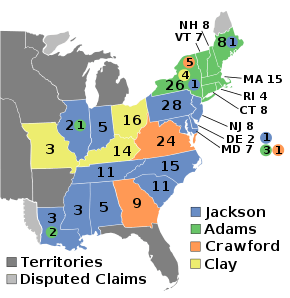

By 1824, the Federalist Party had largely collapsed as a national party, and the 1824 presidential election was waged by competing members of the Democratic-Republican Party.[88] The party's congressional nominating caucus was largely ignored, and candidates were instead nominated by state legislatures.[89] Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, former Speaker of the House Henry Clay, Secretary of the Treasury William Crawford, and General Andrew Jackson emerged as the major candidates in the election.[90] The regional strength of each candidate played an important role in the election; Adams was popular in New England, Clay and Jackson were strong in the West, and Jackson and Crawford competed for the South.[90]

As no candidate won a majority of the electoral vote in the 1824 election, the House of Representatives held a contingent election to determine the president.[91] Clay personally disliked Adams but nonetheless supported him in the contingent election over Crawford, who opposed Clay's nationalist policies, and Jackson, whom Clay viewed as a potential tyrant.[lower-alpha 3] With Clay's backing, Adams won the contingent election.[92] After Clay accepted appointment as Secretary of State, Jackson's supporters claimed that Adams and Clay had reached a "Corrupt Bargain" in which Adams promised Clay the appointment in return for Clay's support in the contingent election.[91] Jackson, who was deeply angered by the result of the contingent election, returned to Tennessee, where the state legislature quickly nominated him for president in the 1828 election.[93]

Final years, 1825–1829

Adams shared Monroe's goal of ending partisan conflict, and his Cabinet included individuals of various ideological and regional backgrounds.[94] In his 1825 annual message to Congress, Adams presented a comprehensive and ambitious agenda, calling for major investments in internal improvements as well as the creation of a national university, a naval academy, and a national astronomical observatory.[95] His requests to Congress galvanized the opposition, spurring the creation of an anti-Adams congressional coalition consisting of supporters of Jackson, Crawford, and Vice President Calhoun.[96] Following the 1826 elections, Calhoun and Martin Van Buren (who brought along many of Crawford's supporters) agreed to throw their support behind Jackson in the 1828 election.[97] In the press, the two major political factions were referred to as "Adams Men" and "Jackson Men".[98]

The Jacksonians formed an effective party apparatus that adopted many modern campaign techniques and emphasized Jackson's popularity and the supposed corruption of Adams and the federal government.[99] Though Jackson did not articulate a detailed political platform in the same way that Adams did, his coalition was united in opposition to Adams's reliance on government planning and tended to favor the opening of Native American lands to white settlement.[100] Ultimately, Jackson won 178 of the 261 electoral votes and just under 56 percent of the popular vote.[101] Jackson won 50.3 percent of the popular vote in the free states and 72.6 percent of the vote in the slave states.[102] The election marked the permanent end of the Era of Good Feelings and the start of the Second Party System. The dream of non-partisan politics, shared by Monroe, Adams, and many earlier leaders, was shattered, replaced with Van Buren's ideal of partisan battles between legitimated political parties.[103]

Party name

In the 1790s, political parties were new in the United States and people were not accustomed to having formal names for them. There was no single official name for the Democratic-Republican Party, but party members generally called themselves Republicans and voted for what they called the "Republican party", "republican ticket" or "republican interest".[104][105] Jefferson and Madison often used the terms "republican" and "Republican party" in their letters.[106] As a general term (not a party name), the word republican had been in widespread usage from the 1770s to describe the type of government the break-away colonies wanted to form: a republic of three separate branches of government derived from some principles and structure from ancient republics; especially the emphasis on civic duty and the opposition to corruption, elitism, aristocracy and monarchy.[107]

The term "Democratic-Republican" was used by contemporaries only occasionally,[16] but is used by some modern sources,[108] partly to distinguish this party from the present-day Republican Party. Some present-day sources describe the party as the "Jeffersonian Republicans".[109][110] Other sources have labeled the party as the "Democratic Party",[111][112][113] though that term was often used pejoratively,[114][115] and the party is not to be confused with the present-day Democratic Party.

Ideology

The Democratic-Republican Party saw itself as a champion of republicanism and denounced the Federalists as supporters of monarchy and aristocracy.[116] Ralph Brown writes that the party was marked by a "commitment to broad principles of personal liberty, social mobility, and westward expansion."[117] Political scientist James A. Reichley writes that "the issue that most sharply divided the Jeffersonians from the Federalists was not states rights, nor the national debt, nor the national Bank... but the question of social equality."[118] In a world in which few believed in democracy or egalitarianism, Jefferson's belief in political equality for white men stood out from many of the other Founding Fathers of the United States, who held that the rich and powerful should lead society. Jefferson advocated a philosophy that historians would later call Jeffersonian democracy, which was marked by his belief in agrarianism and strict limits on the national government.[119] Influenced by the Jeffersonian belief in equality, by 1824 all but three states had removed property-owning requirements for voting.[120]

Though open to some redistributive measures, Jefferson saw a strong centralized government as a threat to freedom.[121] Thus, the Democratic-Republicans opposed Federalist efforts to build a strong, centralized state, and resisted the establishment of a national bank, the build-up of the army and the navy, and passage of the Alien and Sedition Acts.[122] Jefferson was especially averse to a national debt, which he believed to be inherently dangerous and immoral.[123] After the party took power in 1800, Jefferson became increasingly concerned about foreign intervention and more open to programs of economic development conducted by the federal government. In an effort to promote economic growth and the development of a diversified economy, Jefferson's Democratic-Republican successors would oversee the construction of numerous federally funded infrastructure projects and implement protective tariffs.[124]

While economic policies were the original catalyst to the partisan split between the Democratic-Republicans and the Federalists, foreign policy was also a major factor that divided the parties. Most Americans supported the French Revolution prior to the Execution of Louis XVI in 1793, but Federalists began to fear the radical egalitarianism of the revolution as it became increasingly violent.[18] Jefferson and other Democratic-Republicans defended the French Revolution.[125] until Napoleon ascended to power between 1797 and 1803.[126] Democratic-Republican foreign policy was marked by support for expansionism, as Jefferson championed the concept of an "Empire of Liberty" that centered on the acquisition and settlement of western territories.[127] Under Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe, the United States completed the Louisiana Purchase, acquired Spanish Florida, and reached a treaty with Britain providing for shared sovereignty over Oregon Country. In 1823, the Monroe administration promulgated the Monroe Doctrine, which reiterated the traditional U.S. policy of neutrality with regard to European wars and conflicts, but declared that the United States would not accept the recolonization of any country by its former European master.[128] The Monroe Doctrine would be the cornerstone of American foreign policy for several decades.

Slavery

From the foundation of the party, slavery divided the Democratic-Republicans. Many Southern Democratic-Republicans, especially from the Deep South, defended the institution. Jefferson and many other Democratic-Republicans from Virginia held an ambivalent view on slavery; Jefferson believed it was an immoral institution, but he opposed the immediate emancipation of all slaves on economic grounds.[129] Meanwhile, Northern Democratic-Republicans often took stronger anti-slavery positions than their Federalist counterparts, supporting measures like the abolition of slavery in Washington. In 1807, with President Jefferson's support, Congress outlawed the international slave trade, doing so at the earliest possible date allowed by the Constitution.[130]

After the War of 1812, Southerners increasingly came to view slavery as a beneficial institution rather than an unfortunate economic necessity, further polarizing the party over the issue.[130] Anti-slavery Northern Democratic-Republicans held that slavery was incompatible with the equality and individual rights promised by the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. They further held that slavery had been permitted under the Constitution only as a local and impermanent exception, and thus, slavery should not be allowed to spread outside of the original thirteen states. The anti-slavery positions developed by Northern Democratic-Republicans would influence later anti-slavery parties, including the Free Soil Party and the Republican Party.[131] Some Democratic-Republicans from the border states, including Henry Clay, continued to adhere to the Jeffersonian view of slavery as a necessary evil; many of these leaders joined the American Colonization Society, which proposed the voluntary recolonization of Africa as part of a broader plan for the gradual emancipation of slaves.[132]

Base of support

Madison and Jefferson formed the Democratic-Republican Party from a combination of former Anti-Federalists and supporters of the Constitution who were dissatisfied with the Washington administration's policies.[133] Nationwide, Democratic-Republicans were strongest in the South, and many of party's leaders were wealthy Southern slaveowners. The Democratic-Republicans also attracted middle class Northerners, such as artisans, farmers, and lower-level merchants, who were eager to challenge the power of the local elite.[134] Every state had a distinct political geography that shaped party membership; in Pennsylvania, the Republicans were weakest around Philadelphia and strongest in Scots-Irish settlements in the west.[135] The Federalists had broad support in New England, but in other places they relied on wealthy merchants and landowners.[136] After 1800, the Federalists collapsed in the South and West, though the party remained competitive in New England and in some Mid-Atlantic states.[137]

Factions

Historian Sean Wilentz writes that, after assuming power in 1801, the Democratic-Republicans began to factionalize into three main groups: moderates, radicals, and Old Republicans.[138] The Old Republicans, led by John Randolph, were a loose group of influential Southern plantation owners who strongly favored states' rights and denounced any form of compromise with the Federalists. The radicals consisted of a wide array of individuals from different sections of the country who were characterized by their support for far-reaching political and economic reforms; prominent radicals include William Duane and Michael Leib, who jointly led a powerful political machine in Philadelphia. The moderate faction consisted of many former supporters of the ratification of the Constitution, including James Madison, who were more accepting of Federalist economic programs and sought conciliation with moderate Federalists.[139]

After 1810, a younger group of nationalist Democratic-Republicans, led by Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun, rose to prominence. These nationalists favored federally funded internal improvements and high tariffs, positions that would form the basis for Clay's American System.[140] In addition to its base among the leaders of Clay and Calhoun's generation, nationalist policies also proved attractive to many older Democratic-Republicans, including James Monroe.[141] The Panic of 1819 sparked a backlash against nationalist policies, and many of those opposed to the nationalist policies rallied around William H. Crawford until he had a major stroke in 1823.[142] After the 1824 election, most of Crawford's followers, including Martin Van Buren, gravitated to Andrew Jackson, forming a major part of the coalition that propelled Jackson to victory in the 1828 election.[143]

Organizational strategy

The Democratic-Republican Party invented campaign and organizational techniques that were later adopted by the Federalists and became standard American practice. It was especially effective in building a network of newspapers in major cities to broadcast its statements and editorialize its policies.[144] Fisher Ames, a leading Federalist, used the term "Jacobin" to link members of Jefferson's party to the radicals of the French Revolution. He blamed the newspapers for electing Jefferson and wrote they were "an overmatch for any Government.... The Jacobins owe their triumph to the unceasing use of this engine; not so much to skill in use of it as by repetition".[145]

As one historian explained: "It was the good fortune of the Republicans to have within their ranks a number of highly gifted political manipulators and propagandists. Some of them had the ability... to not only see and analyze the problem at hand but to present it in a succinct fashion; in short, to fabricate the apt phrase, to coin the compelling slogan and appeal to the electorate on any given issue in language it could understand". Outstanding propagandists included editor William Duane (1760–1835) and party leaders Albert Gallatin, Thomas Cooper and Jefferson himself.[146] Just as important was effective party organization of the sort that John J. Beckley pioneered. In 1796, he managed the Jefferson campaign in Pennsylvania, blanketing the state with agents who passed out 30,000 hand-written tickets, naming all 15 electors (printed tickets were not allowed). Beckley told one agent: "In a few days a select republican friend from the City will call upon you with a parcel of tickets to be distributed in your County. Any assistance and advice you can furnish him with, as to suitable districts & characters, will I am sure be rendered". Beckley was the first American professional campaign manager and his techniques were quickly adopted in other states.[147]

The emergence of the new organizational strategies can be seen in the politics of Connecticut around 1806, which have been well documented by Cunningham. The Federalists dominated Connecticut, so the Republicans had to work harder to win. In 1806, the state leadership sent town leaders instructions for the forthcoming elections. Every town manager was told by state leaders "to appoint a district manager in each district or section of his town, obtaining from each an assurance that he will faithfully do his duty". Then the town manager was instructed to compile lists and total the number of taxpayers and the number of eligible voters, find out how many favored the Republicans and how many the Federalists and to count the number of supporters of each party who were not eligible to vote but who might qualify (by age or taxes) at the next election. These highly detailed returns were to be sent to the county manager and in turn were compiled and sent to the state manager. Using these lists of potential voters, the managers were told to get all eligible people to town meetings and help the young men qualify to vote. The state manager was responsible for supplying party newspapers to each town for distribution by town and district managers.[148] This highly coordinated "get-out-the-vote" drive would be familiar to modern political campaigners, but was the first of its kind in world history.

Legacy

The coalition of Jacksonians, Calhounites, and Crawfordites built by Jackson and Van Buren would become the Democratic Party, which dominated presidential politics in the decades prior to the Civil War. Supporters of Adams and Clay would form the main opposition to Jackson as the National Republican Party. The National Republicans in turn eventually formed part of the Whig Party, which was the second major party in the United States between the 1830s and the early 1850s.[103] The diverse and changing nature of the Democratic-Republican Party allowed both major parties to claim that they stood for Jeffersonian principles.[149] Historian Daniel Walker Howe writes that Democrats traced their heritage to he "Old Republicanism of Macon and Crawford", while the Whigs looked to "the new Republican nationalism of Madison and Gallatin."[150]

The Whig Party fell apart in the 1850s due to divisions over the expansion of slavery into new territories. The modern Republican Party was formed in 1854 to oppose the expansion of slavery, and many former Whig Party leaders joined the newly formed anti-slavery party.[151] The Republican Party sought to combine Jefferson's ideals of liberty and equality with Clay's program of using an active government to modernize the economy.[152] The Democratic-Republican Party inspired the name and ideology of the Republican Party, but is not directly connected to that party.[153][154]

Fear of a large debt is a major legacy of the party. Andrew Jackson believed the national debt was a "national curse" and he took special pride in paying off the entire national debt in 1835.[155] Politicians ever since have used the issue of a high national debt to denounce the other party for profligacy and a threat to fiscal soundness and the nation's future.[156]

Electoral history

Presidential elections

| Election | Ticket | Popular vote | Electoral vote | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presidential nominee | Running mate | Percentage | Electoral votes | Ranking | |

| 1796 | Thomas Jefferson[upper-alpha 1] | Aaron Burr[upper-alpha 2] | 46.6 | 68 / 138 |

2 |

| 1800 | 61.4 | 73 / 138 |

1 | ||

| 1804 | George Clinton | 72.8 | 162 / 176 |

1 | |

| 1808 | James Madison | 64.7 | 122 / 176 |

1 | |

| 1812 | Elbridge Gerry | 50.4 | 128 / 217 |

1 | |

| DeWitt Clinton[upper-alpha 3] | Jared Ingersoll | 47.6 | 89 / 217 |

2 | |

| 1816 | James Monroe | Daniel D. Tompkins | 68.2 | 183 / 217 |

1 |

| 1820 | 80.6 | 231 / 232 |

1 | ||

| 1824[upper-alpha 4] | Andrew Jackson | John C. Calhoun | 41.4 | 99 / 261 |

1 |

| John Quincy Adams | 30.9 | 84 / 261 |

2 | ||

| William H. Crawford | Nathaniel Macon | 11.2 | 41 / 261 |

3 | |

| Henry Clay | Nathan Sanford | 13 | 37 / 261 |

4 | |

- In his first presidential run, Jefferson did not win the presidency, and Burr did not win the vice presidency. However, under the pre-12th Amendment election rules, Jefferson won the vice presidency due to dissension among Federalist electors.

- In their second presidential run, Jefferson and Burr received the same number of electoral votes. Jefferson was subsequently chosen as President by the House of Representatives.

- While commonly labeled as the Federalist candidate, Clinton technically ran as a Democratic-Republican and was not nominated by the Federalist party itself, the latter simply deciding not to field a candidate. This did not prevent endorsements from state Federalist parties (such as in Pennsylvania), but he received the endorsement from the New York state Democratic-Republicans as well.

- William H. Crawford and Albert Gallatin were nominated for president and vice-president by a group of 66 Congressmen that called itself the "Democratic members of Congress".[157] Gallatin later withdrew from the contest. Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay ran as Republicans, although they were not nominated by any national body. While Jackson won a plurality in the electoral college and popular vote, he did not win the constitutionally required majority of electoral votes to be elected president. The contest was thrown to the House of Representatives, where Adams won with Clay's support. The electoral college chose John C. Calhoun for vice president.

Congressional representation

The affiliation of many Congressmen in the earliest years is an assignment by later historians. The parties were slowly coalescing groups; at first there were many independents. Cunningham noted that only about a quarter of the House of Representatives up until 1794 voted with Madison as much as two-thirds of the time and another quarter against him two-thirds of the time, leaving almost half as fairly independent.[158]

| Congress | Years | Senate[159] | House of Representatives[160] | President | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Anti- Admin |

Pro- Admin |

Others | Vacancies | Total | Anti- Admin |

Pro- Admin |

Others | Vacancies | ||||||

| 1st | 1789–1791 | 26 | 8 | 18 | — | — | 65 | 28 | 37 | — | — | George Washington | |||

| 2nd | 1791–1793 | 30 | 13 | 16 | — | 1 | 69 | 30 | 39 | — | — | ||||

| 3rd | 1793–1795 | 30 | 14 | 16 | — | — | 105 | 54 | 51 | — | — | ||||

| Congress | Years | Total | Democratic- Republicans |

Federalists | Others | Vacancies | Total | Democratic- Republicans |

Federalists | Others | Vacancies | President | |||

| 4th | 1795–1797 | 32 | 11 | 21 | — | — | 106 | 59 | 47 | — | — | George Washington | |||

| 5th | 1797–1799 | 32 | 10 | 22 | — | — | 106 | 49 | 57 | — | — | John Adams | |||

| 6th | 1799–1801 | 32 | 10 | 22 | — | — | 106 | 46 | 60 | — | — | ||||

| 7th | 1801–1803 | 34 | 17 | 15 | — | 2 | 107 | 68 | 38 | — | 1 | Thomas Jefferson | |||

| 8th | 1803–1805 | 34 | 25 | 9 | — | — | 142 | 103 | 39 | — | — | ||||

| 9th | 1805–1807 | 34 | 27 | 7 | — | — | 142 | 114 | 28 | — | — | ||||

| 10th | 1807–1809 | 34 | 28 | 6 | — | — | 142 | 116 | 26 | — | — | ||||

| 11th | 1809–1811 | 34 | 27 | 7 | — | — | 142 | 92 | 50 | — | — | James Madison | |||

| 12th | 1811–1813 | 36 | 30 | 6 | — | — | 143 | 107 | 36 | — | — | ||||

| 13th | 1813–1815 | 36 | 28 | 8 | — | — | 182 | 114 | 68 | — | — | ||||

| 14th | 1815–1817 | 38 | 26 | 12 | — | — | 183 | 119 | 64 | — | — | ||||

| 15th | 1817–1819 | 42 | 30 | 12 | — | — | 185 | 146 | 39 | — | — | James Monroe | |||

| 16th | 1819–1821 | 46 | 37 | 9 | — | — | 186 | 160 | 26 | — | — | ||||

| 17th | 1821–1823 | 48 | 44 | 4 | — | — | 187 | 155 | 32 | — | — | ||||

| 18th | 1823–1825 | 48 | 43 | 5 | — | — | 213 | 189 | 24 | — | — | ||||

| Congress | Years | Total | Pro-Jackson | Pro-Adams | Others | Vacancies | Total | Pro-Jackson | Pro-Adams | Others | Vacancies | President | |||

| 19th | 1825–1827 | 48 | 26 | 22 | — | — | 213 | 104 | 109 | — | — | John Quincy Adams | |||

| 20th | 1827–1829 | 48 | 27 | 21 | — | — | 213 | 113 | 100 | — | — | ||||

| Senate | House of Representatives | ||||||||||||||

See also

Explanatory notes

- Party members generally, but not exclusively, referred to it as the Republican Party, although the word Republican is not to be confused with the modern politics of the current Republican Party. Partly to distinguish this party from the current Republican Party, political scientists have used other names for the party such as "Democratic-Republican", "Jeffersonian Republicans" and the pejorative "Democratic Party", not to be confused with the present-day Democratic Party. For details and references, see the section Republican Party name.

- Prior to the ratification of the Twelfth Amendment in 1804, each member of the Electoral College cast two votes, with no distinction made between electoral votes for president and electoral votes for vice president. Under these rules, an individual who received more votes than any other candidate, and received votes from a majority of the electors, was elected as president. If neither of those conditions were met, the House of Representatives would select the president through a contingent election in which each state delegation received one vote. After the selection of the president, the individual who finished with the most votes was elected as vice president, with the Senate holding a contingent election in the case of a tie.[25]

- Clay himself was not eligible in the contingent election because the House could only choose from the top-three candidates in the electoral vote tally. Clay finished a close fourth to Crawford in the electoral vote.[92]

References

- "Democratic-Republican Party". Encyclopædia Britannica. July 20, 1998. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

The Republicans contended that the Federalists harboured aristocratic attitudes and that their policies placed too much power in the central government and tended to benefit the affluent at the expense of the common man.

- Ohio History Connection. "Democratic-Republican Party". Ohio History Central. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

Democratic-Republicans favored keeping the U.S. economy based on agriculture and said that the U.S. should serve as the agricultural provider for the rest of the world [...]. Economically, the Democratic-Republicans wanted to remain a predominantly agricultural nation, [...].

- Beasley, James R. (1972). "Emerging Republicanism and the Standing Order: The Appropriation Act Controversy in Connecticut, 1793 to 1795". The William and Mary Quarterly. 29 (4): 604. doi:10.2307/1917394. JSTOR 1917394.

- Ornstein, Allan (March 9, 2007). Class Counts: Education, Inequality, and the Shrinking Middle Class. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 56–58. ISBN 9780742573727.

- Larson, Edward J. (2007). A Magnificent Catastrophe: The Tumultuous Election of 1800, America's First Presidential Campaign. p. 21. ISBN 9780743293174.

The divisions between Adams and Jefferson were exasperated by the more extreme views expressed by some of their partisans, particularly the High Federalists led by Hamilton on what was becoming known as the political right, and the democratic wing of the Republican Party on the left, associated with New York Governor George Clinton and Pennsylvania legislator Albert Gallatin, among others.

- Knott, Stephen (October 4, 2016). "George Washington: Campaigns and Elections". Charlottesville, Virginia: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Archived from the original on July 28, 2017. Retrieved July 14, 2017.

- Reichley (2000), pp. 25, 29

- Ferling 2009, pp. 282–284

- Ferling 2009, pp. 292–293

- Ferling 2009, pp. 293–298

- Bordewich 2016, pp. 244–252

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 44–45

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 45–48

- Wood 2009, pp. 150–151

- Thompson (1980), pp. 174–175

- See The Aurora General Advertiser (Philadelphia), April. 30, 1795, p. 3; New Hampshire Gazette (Portsmouth), October 15, 1796, p. 3; Claypoole's American Daily Advertiser (Philadelphia), October 10, 1797, p. 3; Columbian Centinel (Boston), September 15, 1798, p. 2; Alexandria (VA) Times, October 8, 1798, p. 2; Daily Advertiser (New York), September 22, 1800, p. 2 & November 25, 1800, p. 2; The Oracle of Dauphin (Harrisburg), October 6, 1800, p. 3; Federal Gazette (Baltimore), October 23, 1800, p. 3; The Spectator (New York), October 25, 1800, p. 3; Poulson's American Daily Advertiser (Philadelphia), November 19, 1800, p. 3; Windham (CT) Herald, November 20, 1800, p. 2; City Gazette (Charleston), November 22, 1800, p. 2; The American Mercury (Hartford), November 27, 1800, p. 3; and Constitutional Telegraphe (Boston), November 29, 1800, p. 3.

After 1802, some local organizations slowly began merging "Democratic" into their own name and became known as the "Democratic Republicans". Examples include 1802, 1803, 1804, 1804, 1805, 1806, 1807, 1808, 1809. - Wood 2009, pp. 161–162

- Ferling 2009, pp. 299–302, 309–311

- Ferling 2009, pp. 323–328, 338–344

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 60, 64–65

- Ferling 2003, pp. 397–400

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 72–73, 86

- McDonald 1974, pp. 178–181

- Taylor, C. James (October 4, 2016). "John Adams: Campaigns and Elections". Charlottesville, Virginia: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- Neale, Thomas H. (November 3, 2016), Contingent Election of the President and Vice President by Congress: Perspectives and Contemporary Analysis (PDF), Congressional Research Service

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 77–78

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 80–82

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 78–79

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 85–87

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 86, 91–92

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 92–94

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 97–98

- Brown 1975, pp. 165–166

- Brown 1975, pp. 198–200

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 99–100

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 95–97

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 101–102

- Wood, 2009, pp. 291–296.

- Bailey, 2007, p. 216.

- Chernow, 2004, p. 671.

- McDonald, 1976, pp. 41–42

- Wood, 2009, p. 293.

- Meacham, 2012, p. 387.

- Appleby, 2003, pp. 65–69

- Appleby, 2003, pp. 7–8, 61–63

- Wood, 2009, pp. 357–359.

- Appleby, 2003, pp. 63–64

- Nugent, 2008, pp. 61–62

- Wilentz, 2005, p. 108.

- Rodriguez, 2002, p. 97.

- Appleby, 2003, pp. 64–65

- Wood, 2009, pp. 369–370.

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 115–116

- Rutland (1990), p. 12

- Rutland (1990), p. 13

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 130–134

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 134–135

- Wills 2002, pp. 94–96.

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 147–148

- Wills 2002, pp. 95–96.

- Rutland, James Madison: The Founding Father, pp. 217–24

- Wilentz (2005), p. 156

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 156–159

- Wills 2002, pp. 97–98.

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 160–161

- Rutland (1990), pp. 186–188

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 175–176

- Rutland (1990), pp. 192, 201

- Rutland (1990), pp. 211–212

- Rutland (1990), pp. 20, 68–70

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 181–182

- Rutland (1990), pp. 195–198

- Howe (2007), pp. 82–84

- Cunningham 1996, pp. 15–18.

- Cunningham 1996, pp. 18–19.

- Howe, pp. 93–94.

- Cunningham 1996, pp. 19–21.

- "James Monroe: Domestic Affairs". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. October 4, 2016. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 206–207

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 209–210, 251–252

- Wilentz (2005), p. 217

- Howe (2007), p. 147

- Cunningham 1996, pp. 28–29.

- Wilentz, 2004, p. 376: "[T]he sectional divisions among the Jeffersonian Republicans…offers historical paradoxes…in which hard-line slaveholding Southern Republicans rejected the egalitarian ideals of the slaveholder [Thomas] Jefferson while the antislavery Northern Republicans upheld them – even as Jefferson himself supported slavery's expansion on purportedly antislavery grounds.

- Wilentz, 2004, pp. 380, 386.

- Cunningham 1996, pp. 101–103.

- Cunningham 1996, pp. 103–104.

- Parsons 2009, pp. 70–72.

- Parsons 2009, pp. 79–86.

- Kaplan 2014, pp. 386–389.

- Kaplan 2014, pp. 391–393, 398.

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 254–255

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 256–257

- Parsons 2009, pp. 106–107.

- Kaplan 2014, pp. 402–403.

- Parsons 2009, pp. 114–120.

- Parsons 2009, pp. 127–128.

- Howe 2007, p. 251

- Howe 2007, pp. 275–277

- Howe 2007, pp. 279–280

- Parsons 2009, pp. 181–183.

- Howe 2007, pp. 281–283

- Parsons 2009, pp. 185–187, 195.

- For examples of original quotes and documents from various states, see Cunningham, Noble E., Jeffersonian Republicans: The Formation of Party Organization: 1789–1801 (1957), pp. 48, 63–66, 97, 99, 103, 110, 111, 112, 144, 151, 153, 156, 157, 161, 163, 188, 196, 201, 204, 213, 218 and 234.

See also "Address of the Republican committee of the County of Gloucester, New-Jersey Archived October 21, 2017, at the Wayback Machine", Gloucester County, December 15, 1800. - Jefferson used the term "republican party" in a letter to Washington in May 1792 to refer to those in Congress who were his allies and who supported the existing republican constitution. "Thomas Jefferson to George Washington, May 23, 1792". Retrieved October 4, 2006. At a conference with Washington a year later, Jefferson referred to "what is called the republican party here". Bergh, ed. Writings of Thomas Jefferson (1907) 1:385, 8:345

- "James Madison to Thomas Jefferson, March 2, 1794". Retrieved October 14, 2006. "I see by a paper of last evening that even in New York a meeting of the people has taken place, at the instance of the Republican party, and that a committee is appointed for the like purpose." See also: Smith, 832.

"James Madison to William Hayward, March 21, 1809. Address to the Republicans of Talbot Co. Maryland". Retrieved October 27, 2006.

"Thomas Jefferson to John Melish, January 13, 1813". Retrieved October 27, 2006. "The party called republican is steadily for the support of the present constitution"

"James Madison to Baltimore Republican Committee, April 22, 1815". Retrieved October 27, 2006.

"James Madison to William Eustis, May 22, 1823". Retrieved October 27, 2006. Transcript. "The people are now able every where to compare the principles and policy of those who have borne the name of Republicans or Democrats with the career of the adverse party and to see and feel that the former are as much in harmony with the Spirit of the Nation as the latter was at variance with both." - Banning, 79–90.

- Brown (1999), p. 17

- Onuf, Peter (August 12, 2019). "THOMAS JEFFERSON: IMPACT AND LEGACY". Miller Center.

- "Jeffersonian Republican Party". Encyclopedia.com. The Gale Group. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- de Tocqueville, Alexis. Democracy in America. p. Volume One, Part II, Ch. II.

There had always been something artificial in the means and temporary in the resources which maintained the Federalists; it was the virtues and talents of their leaders, combined with lucky circumstances, which had brought them to power. When the Republicans came in turn to power, the opposing party seemed to be engulfed by a sudden flood. A huge majority declared against it, and suddenly finding itself so small a minority, it at once fell into despair. Thenceforth the Republican, or Democratic, party has gone on from strength to strength and taken possession of the whole of society.

- Webster, Noah (1843). A Collection of Papers on Political, Literary, and Moral Subjects. Webster & Clark. p. 332.

From the time when the anti-federal party assumed the more popular appellation of republican, which was soon after the arrival of the French minister in 1793, that epithet became a powerful instrument in the process of making proselytes to the party. The influence of names on the mass of mankind, was never more distinctly exhibited, than in the increase of the democratic party in the United States.

- Larson, Edward J. (2007). A Magnificent Catastrophe: The Tumultuous Election of 1800, America's First Presidential Campaign. p. 17. ISBN 9780743293174.

Although Jefferson did not oppose ratification, he became a leading voice within the faction that included both Anti-Federalists, who had opposed ratification, and more moderate critics of a strong national government. Collectively, its members became known as Republicans or, later, Democrats.

- Janda, Kenneth; Berry, Jeffrey M.; Goldman, Jerry; Deborah, Deborah (2015). The Challenge of Democracy: American Government in Global Politics 13th ed. Cengage Learning. p. 212. ISBN 9781305537439.

- In a private letter in September 1798, George Washington wrote, "You could as soon as scrub the blackamore white, as to change the principles of a profest Democrat; and that he will leave nothing unattempted to overturn the Government of this Country." George Washington (1939). The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources 1745-1799 Volume 36 August 4, 1797-October 28, 1798. p. 474. ISBN 9781623764463.

- James Roger Sharp, American Politics in the Early Republic: The New Nation in Crisis (1993).

- Brown (1999), p. 19

- Reichley (2000), p. 52

- Appleby, 2003, pp. 1–5

- Reichley (2000), p. 57

- Reichley (2000), p. 55–56

- Reichley (2000), pp. 51–52

- McDonald, 1976, pp. 42–43

- Brown (1999), pp. 19–20

- Reichley (2000), pp. 35–36

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 108

- Wood (2009), pp. 357–358

- "James Monroe: Foreign Affairs". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. October 4, 2016. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 136–137

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 218–221

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 225–227

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 228–229

- Reichley (2000), pp. 36–37

- Wood 2009, pp. 166–168

- Klein, 44.

- Wood 2009, pp. 168–171

- Reichley (2000), p. 54

- Wilentz (2005), p. 100

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 105–107

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 144–148

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 202–203

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 241–242

- Wilentz (2005), pp. 294–296

- Jeffrey L. Pasley. "The Tyranny of Printers": Newspaper Politics in the Early American Republic (2003)

- Cunningham (1957), 167.

- Tinkcom, 271.

- Cunningham, Noble E. (1956). "John Beckley: An Early American Party Manager". The William and Mary Quarterly. 13 (1): 40–52. doi:10.2307/1923388. JSTOR 1923388.

- Cunningham (1963), 129.

- Brown (1999), pp. 18–19

- Howe (2007), p. 582

- "The Origin of the Republican Party, A.F. Gilman, Ripon College, 1914". Content.wisconsinhistory.org. Retrieved January 17, 2012.

- Gould (2003), p. 14.

- Howe (2007), pp. 66, 275, 897

- Lipset, Seymour Martin (1960). Political Man: The Social Bases of Politics. Garden City, N.Y.,: Doubleday. p. 292.

- Remini, Robert V. (2008). Andrew Jackson. Macmillan. p. 180. ISBN 9780230614703.

- Nagel, Stuart (1994). Encyclopedia of Policy Studies (2nd ed.). Taylor & Francis. pp. 503–504. ISBN 9780824791421.

- "Anti-Caucus/Caucus". Washington Republican. February 6, 1824. Archived from the original on August 31, 2017. Retrieved November 17, 2019.

- Cunningham (1957), 82.

- "Party Division". United States Senate.

- "Party Divisions of the House of Representatives, 1789 to Present". United States House of Representatives.

Works cited

- Appleby, Joyce Oldham (2003). Thomas Jefferson: The American Presidents Series: The 3rd President, 1801–1809. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-0805069242.

- Bailey, Jeremy D. (2007). Thomas Jefferson and Executive Power. Twenty-First Century Books. ISBN 978-1139466295.

- Banning, Lance. The Jeffersonian Persuasion: Evolution of a Party Ideology (1980).

- Bordewich, Fergus M. (2016). The First Congress. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-45169193-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brown, David (1999). "Jeffersonian Ideology and the Second Party System". Wiley. 62 (1): 17–30. JSTOR 24450533.

- Brown, Ralph A. (1975). The Presidency of John Adams. American Presidency Series. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0134-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chernow, Ron (2004). Alexander Hamilton. Penguin Press. ISBN 978-1594200090.

- Cunningham, Noble (1996). The Presidency of James Monroe. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0728-5.

- Cunningham, Noble E., Jr. Jeffersonian Republicans: The formation of Party Organization: 1789–1801 (1957).

- Cunningham, Noble E., Jr. The Jeffersonian Republicans in Power: Party Operations 1801–1809 (1963).

- Ferling, John (2003). A Leap in the Dark: The Struggle to Create the American Republic. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515924-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ferling, John (2009). The Ascent of George Washington: The Hidden Political Genius of an American Icon. New York: Bloomsbury Press. ISBN 978-1-59691-465-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gould, Lewis. Grand Old Party: A History of the Republicans (2003) (ISBN 0-375-50741-8) concerns the party founded in 1854.

- Howe, Daniel Walker (2007). What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848. Oxford History of the United States. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507894-7. OCLC 122701433.

- Kaplan, Fred (2014). John Quincy Adams: American Visionary. HarperCollins.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McDonald, Forrest (1974). The Presidency of George Washington. American Presidency. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0359-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McDonald, Forrest (1976). The Presidency of Thomas Jefferson. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0700603305.

- Meacham, Jon (2012). Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power. Random House LLC. ISBN 978-0679645368.

- Nugent, Walter (2008). Habits of Empire: A History of American Expansion. Knopf. ISBN 978-1400042920.

- Parsons, Lynn H. (2009). The Birth of Modern Politics: Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, and the Election of 1828. Oxford Univ. Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reichley, A. James (2000) [1992]. The Life of the Parties: A History of American Political Parties (Paperback ed.). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 0-7425-0888-9.

- Rutland, Robert A. The Presidency of James Madison (Univ. Press of Kansas, 1990). ISBN 978-0700604654.

- Thompson, Harry C. (1980). "The Second Place in Rome: John Adams as Vice President". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 10 (2): 171–178. JSTOR 27547562.

- Tinkcom, Harry M. The Republicans and Federalists in Pennsylvania, 1790–1801 (1950).

- Wilentz, Sean (2005). The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-05820-4.

- Wills, Garry. James Madison: The American Presidents Series: The 4th President, 1809-1817 (Times Books, 2002).

- Wood, Gordon S. (2009). Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815. Oxford History of the United States. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-503914-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Adams, Henry, History of the United States during the Administrations of Thomas Jefferson (1889; Library of America ed. 1987).

- Adams, Henry, History of the United States during the Administrations of James Madison (1891; Library of America ed. 1986).

- Beard, Charles A. Economic Origins of Jeffersonian Democracy (1915).

- Brown, Stuart Gerry. The First Republicans: Political Philosophy and Public Policy in the Party of Jefferson and Madison 1954.

- Chambers, Wiliam Nisbet. Political Parties in a New Nation: The American Experience, 1776–1809 (1963).

- Cornell, Saul. The Other Founders: Anti-Federalism and the Dissenting Tradition in America, 1788–1828 (1999) (ISBN 0-8078-2503-4).

- Cunningham, Noble E., Jr. The Process of Government Under Jefferson (1978).

- Dawson, Matthew Q. Partisanship and the Birth of America's Second Party, 1796–1800: Stop the Wheels of Government. Greenwood, 2000.

- Elkins, Stanley M. and Eric McKitrick. The Age of Federalism (1995), detailed political history of 1790s.

- Ferling, John. Adams Vs. Jefferson: The Tumultuous Election of 1800 (2004) (ISBN 0-19-516771-6).

- Ferling, John (2009). The Ascent of George Washington: The Hidden Political Genius of an American Icon. New York: Bloomsbury Press. ISBN 978-1-59691-465-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gammon, Samuel Rhea. The Presidential Campaign of 1832 (1922).

- Howe, Daniel Walker (2007). What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America 1815–1848. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195078947.

- Klein, Philip Shriver. Pennsylvania Politics, 1817–1832: A Game without Rules 1940.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1965). The Oxford History of the American People. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Onuf, Peter S., ed. Jeffersonian Legacies. (1993) (ISBN 0-8139-1462-0).

- Pasley, Jeffrey L. et al. eds. Beyond the Founders: New Approaches to the Political History of the Early American Republic (2004).

- Ray, Kristofer. "The Republicans Are the Nation? Thomas Jefferson, William Duane, and the Evolution of the Republican Coalition, 1809–1815." American Nineteenth Century History 14.3 (2013): 283–304.

- Risjord, Norman K.; The Old Republicans: Southern Conservatism in the Age of Jefferson (1965) on the Randolph faction.

- Rodriguez, Junius (2002). The Louisiana Purchase: a historical and geographical encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1576071885.

- Sharp, James Roger. American Politics in the Early Republic: The New Nation in Crisis (1993) detailed narrative of 1790s.

- Smelser, Marshall. The Democratic Republic 1801–1815 (1968), survey of political history.

- Van Buren, Martin. Van Buren, Abraham, Van Buren, John, ed. Inquiry Into the Origin and Course of Political Parties in the United States (1867) (ISBN 1-4181-2924-0).

- Wiltse, Charles Maurice. The Jeffersonian Tradition in American Democracy (1935).

- Wilentz, Sean (September 2004). "Jeffersonian Democracy and the Origins of Political Antislavery in the United States: The Missouri Crisis Revisited". Journal of the Historical Society. 4 (3): 375–401. doi:10.1111/j.1529-921X.2004.00105.x.

- Wills, Garry. Henry Adams and the Making of America (2005), a close reading of Henry Adams (1889–1891).

Biographies

- Ammon, Harry (1971). James Monroe: The Quest for National Identity. McGraw-Hill.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cunningham, Noble E. In Pursuit of Reason The Life of Thomas Jefferson (ISBN 0-345-35380-3) (1987).

- Cunningham, Noble E., Jr. "John Beckley: An Early American Party Manager", William and Mary Quarterly, 13 (January 1956), 40–52, in JSTOR.

- Miller, John C. Alexander Hamilton: Portrait in Paradox (1959), full-scale biography.

- Peterson; Merrill D. Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation: A Biography (1975), full-scale biography.

- Remini, Robert. Henry Clay: Statesman for the Union (1991), a standard biography.

- Rutland, Robert A., ed. James Madison and the American Nation, 1751–1836: An Encyclopedia (1994).

- Schachner, Nathan. Aaron Burr: A Biography (1961), full-scale biography.

- Unger, Harlow G.. "The Last Founding Father: James Monroe and a Nation's Call to Greatness" (2009)

- Wiltse, Charles Maurice. John C. Calhoun, Nationalist, 1782–1828 (1944).

State studies

- Beeman, Richard R. The Old Dominion and the New Nation, 1788–1801 (1972), on Virginia politics.

- Formisano, Ronald P. The Transformation of Political Culture. Massachusetts Parties, 1790s–1840s (1984) (ISBN 0-19-503509-7).

- Gilpatrick, Delbert Harold. Jeffersonian Democracy in North Carolina, 1789–1816 (1931).

- Goodman, Paul. The Democratic-Republicans of Massachusetts (1964).

- Prince, Carl E. New Jersey's Jeffersonian Republicans: The Genesis of an Early Party Machine, 1789–1817 (1967).

- Risjord; Norman K. Chesapeake Politics, 1781–1800 (1978) on Virginia and Maryland.

- Young, Alfred F. The Democratic Republicans of New York: The Origins, 1763–1797 (1967).

Newspapers

- Humphrey, Carol Sue The Press of the Young Republic, 1783–1833 (1996).

- Knudson, Jerry W. Jefferson And the Press: Crucible of Liberty (2006) how 4 Republican and 4 Federalist papers covered election of 1800; Thomas Paine; Louisiana Purchase; Hamilton-Burr duel; impeachment of Chase; and the embargo.

- Jeffrey L. Pasley. "The Tyranny of Printers": Newspaper Politics in the Early American Republic (2003) (ISBN 0-8139-2177-5).

- Stewart, Donald H. The Opposition Press of the Federalist Era (1968), highly detailed study of Republican newspapers.

- National Intell & Washington Advertister. January 16, 1801. Issue XXXIII COl. B.

- The complete text, searchable, of all early American newspapers are online at Readex America's Historical Newspapers, available at research libraries.

Primary sources

- Adams, John Quincy. Memoirs of John Quincy Adams: Comprising Portions of His Diary from 1795 to 1848 Volume VII (1875) edited by Charles Francis Adams; (ISBN 0-8369-5021-6). Adams, son of the Federalist president, switched and became a Republican in 1808.

- Cunningham, Noble E., Jr., ed. The Making of the American Party System 1789 to 1809 (1965) excerpts from primary sources.

- Cunningham, Noble E., Jr., ed. Circular Letters of Congressmen to Their Constituents 1789–1829 (1978), 3 vol; reprints the political newsletters sent out by congressmen.

- Kirk, Russell ed. John Randolph of Roanoke: A study in American politics, with selected speeches and letters, 4th ed., Liberty Fund, 1997, 588 pp. ISBN 0-86597-150-1; Randolph was a leader of the "Old Republican" faction.

- Smith, James Morton, ed. The Republic of Letters: The Correspondence of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, 1776–1826 Volume 2 (1994).

.jpg)

.jpeg)

.svg.png)