Kaiserpfalz

The term Kaiserpfalz (German: [ˈkaɪzɐˌpfalts], "imperial palace") or Königspfalz (German: [ˈkøːnɪçsˌpfalts], "royal palace", from Middle High German phal[en]ze to Old High German phalanza from Middle Latin palatia [plural] to Latin palatium "palace"[1]) refers to a number of castles and palaces across the Holy Roman Empire that served as temporary, secondary seats of power for the Holy Roman Emperor in the Early and High Middle Ages. The term was also used more rarely for a bishop who, as a territorial lord (Landesherr), had to provide the king and his entourage with board and lodging, a duty referred to as Gastungspflicht.

Origin of the name

Kaiserpfalz is a German word that is a combination of Kaiser, meaning "emperor", which is derived from "caesar"; and Pfalz, meaning "palace", and itself derived from the Latin palatium, meaning the same (see palace). Likewise Königspfalz is a combination of König, "king", and Pfalz, meaning "royal palace".

Description and purpose

Like their peers in France and England, the medieval emperors of the Holy Roman Empire did not rule from a capital city, but had to maintain personal contact with their vassals on the ground. This was so-called "itinerant kingship"; a sort of "travelling kingdom" (Reisekönigtum).

Because pfalzen were built and used by the king as a ruler within the Holy Roman Empire (rex Romanorum (Römischer König)), the correct historical term is Königspfalz or "royal palace". The term Kaiserpfalz is a 19th-century appellation that overlooks the fact that the king did not bear the title of the Roman Emperor (granted by the Pope) until after his imperial coronation. Unlike a pfalz, where the itinerant ruler enacted his sovereign duties, a royal estate or Königshof is only an economic estate owned by the king, which was only occasionally used by the king on his itinerary.[2]

Unlike the common notion of "palace", a pfalz was not a permanent residence but a place where the emperor stayed for a certain time, usually less than a year; itineraries suggest that the monarch rarely would stay for longer than a few weeks. Moreover, they were not always grand palaces in the accepted sense: some were small castles or fortified hunting lodges, such as Bodfeld in the Harz.

But in the main they were large manor houses (Gutshöfe), that offered catering and accommodation for the king and his many retainers, often running to hundreds of staff, as well as numerous guests and their horses. In Latin, such a royal manor was known as a villa regia or curtis regia. They were located either near the bishop's residences, near important abbeys, near towns the king held or in the countryside in the middle of royal estates. Pfalzen were generally built at intervals of 30 kilometres, which represented a day's journey by horse at that time.

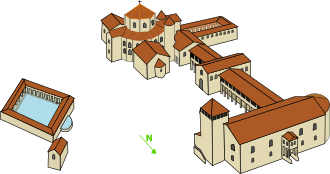

At a minimum, a pfalz consisted of a palas with its Great Hall or Aula Regia, an imperial chapel (Pfalzkapelle) and an estate (Gutshof). It was here that kings and emperors carried out the business of state, held their imperial court sessions and celebrated important church festivals. Each was administered by a count palatine, who executed jurisdiction in the emperor's stead. One of the most important of them would eventually rise to the title of Prince-elector.

The pfalzen that the rulers visited varied depending on their function. Especially important were those palaces in which the kings spent the winter (winter palaces or Winterpfalzen), and the festival palaces (Festtagspfalzen), Easter being the most important and celebrated at Easter palaces (Osterpfalzen). The larger palaces were often in towns that had special rights (e.g. imperial immediacy), but could also be bishop's seats or imperial abbeys.

In the Hohenstaufen era of the Roman-German kingdom, important imperial princes began to demonstrate their claims to power by building their own pfalzen. Important examples of these include Henry the Lion's Dankwarderode Castle in Brunswick and the Wartburg above Eisenach in Thuringia. Both buildings followed the basic design of Hohenstaufen pfalzen and also had the same dimensions.

List of Holy Roman Imperial palaces

Examples of surviving imperial palaces may be found in the town of Goslar and at Düsseldorf-Kaiserswerth.

- Aachen

- Adelberg

- Aibling

- Albisheim

- Altenburg

- Altötting

- Alzey

- Amorbach

- Andernach

- Ansbach

- Arneburg

- Arnstadt

- Aufhausen

- Augsburg

- Baden-Baden

- Balgstädt

- Bamberg

- Bardowick

- Batzenhofen

- Belgern

- Beratzhausen

- Berstadt

- Biebrich

- Bierstadt

- Bingen am Rhein

- Böckelheim

- Bodfeld

- Bodman

- Bonn

- Boppard

- Boyneburg

- Brandenburg

- Braunschweig

- Breisach

- Breitenbach

- Breitingen

- Bremen

- Bruchsal

- Brüggen

- Bürgel

- Bürstadt

- Buxtehude

- Calbe

- Cham

- Cochem

- Corvey

- Dahlen

- Derenburg

- Diedenhofen

- Dollendorf

- Donaueschingen

- Donaustauf

- Donauwörth

- Dornburg

- Dortmund

- Duisburg

- Düren

- Durlach

- Ebersberg

- Ebrach

- Ebsdorf

- Eckartsberga

- Eichstätt

- Eisenberg

- Eisfeld

- Eisleben

- Elten

- Eresburg

- Erfurt

- Ermschwerd

- Erwitte

- Eschwege

- Essen

- Esslingen am Neckar

- Ettenstatt

- Etterzhausen

- Eußerthal

- Flamersheim

- Forchheim

- Frankfurt am Main

- Freiburg im Breisgau

- Freising

- Fritzlar

- Frohse an der Elbe

- Fulda

- Fürth

- Gandersheim

- Gebesee

- Gehren

- Geldersheim

- Gelnhausen

- Germersheim

- Gernrode

- Gernsheim

- Gerstungen

- Giebichenstein

- Gieboldehausen

- Giengen

- Göppingen

- Goslar

- Gottern

- Grebenau

- Grone

- Großseelheim

- Günzburg

- Gustedt

- Hahnbach an der Vils

- Haina

- Halberstadt

- Halle

- Hammerstein

- Harsefeld

- Harzburg

- Haselbach

- Hasselfelde

- Haßloch

- Havelberg

- Heidingsfeld

- Heilbronn

- Heiligenberg

- Heiligenstadt

- Heimsheim

- Helfta

- Helmstedt

- Hemau

- Herbrechtingen

- Herford

- Herrenbreitungen

- Hersfeld

- Herstelle

- Herzberg

- Heßloch

- Hildesheim

- Hilwartshausen

- Hirsau

- Hirschaid

- Hohenaltheim

- Hohenstaufen

- Hohentwiel

- Hohnstedt

- Hollenstedt

- Hornburg

- Ilsenburg

- Imbshausen

- Ingelheim

- Ingolstadt

- Inning

- Kaiserslautern

- Kaiserswerth

- Kamba

- Kassel

- Kastel

- Kaufungen

- Kayna

- Kelheim

- Kelsterbach

- Kessel

- Kirchberg

- Kirchen

- Kirchohsen

- Kissenbrück

- Kissingen

- Kitzingen

- Koblenz

- Köln

- Komburg

- Königsdahlum

- Königslutter

- Konstanz

- Kostheim

- Kraisdorf[3]

- Kreuznach

- Ladenburg

- Lampertheim

- Langen

- Langenau

- Langenzenn

- Laufen

- Lauffen am Neckar[4]

- Lautertal (Oberfranken)

- Leisnig

- Leitzkau

- Lichtenberg

- Limburg an der Haardt

- Lingen

- Lippeham

- Lippspringe

- Lonnerstadt

- Lonsheim

- Lorch

- Lorsch

- Lustenau

- Lügde

- Lüneburg

- Magdeburg

- Mainz

- Markgröningen

- Mecklenburg

- Meißen

- Memleben

- Memmingen

- Mengen

- Mering

- Merseburg

- Minden

- Mindersdorf

- Mirsdorf

- Mögeldorf

- Moosburg

- Mörfelden

- Mosbach

- Mötsch

- Mühlhausen

- Münden

- Münnerstadt

- Münster

- Münstereifel

- Nabburg

- Nanstein

- Nattheim

- Naumburg

- Neuburg

- Neudingen

- Neuenburg

- Neuhausen

- Neuss

- Niederalteich

- Nienburg

- Nierstein

- Nijmegen

- Nordhausen

- Northeim

- Nürnberg

- Nußdorf

- Obertheres

- Ochsenfurt

- Oferdingen

- Ohrdruf

- Ohrum

- Oppenheim

- Oschersleben

- Osnabrück

- Osterhausen

- Osterhofen

- Osterode

- Paderborn

- Passau

- Pegau

- Peiting

- Pforzheim

- Pöhlde

- Pondorf

- Prüm

- Quedlinburg

- Ramspau

- Rasdorf

- Regensburg

- Rehme

- Reibersdorf

- Reichenau

- Rheinbach

- Riekofen

- Ritteburg

- Rochlitz

- Rodach

- Roding

- Rohr

- Rommelhausen

- Rösebeck

- Rosenburg

- Rothenburg ob der Tauber

- Rottweil

- Rüdesheim

- Rülzheim

- Saalfeld

- Säckingen

- Salz

- Salzwedel

- Samswegen

- Sankt Goar

- Sasbach am Kaiserstuhl

- Schattbuch

- Schienen

- Schierling

- Schöningen

- Schüller

- Schwäbisch Gmünd

- Schwäbisch Hall

- Schwarzenbruck

- Schwarzrheindorf

- See, Gem. Lupburg

- Seehausen

- Seidmannsdorf

- Seinstedt

- Seligenstadt

- Sinzig

- Siptenfelde

- Soest

- Sohlingen

- Sömmeringen[5]

- Sontheim an der Brenz

- Speyer

- Stadtamhof

- Staffelsee

- Stallbaum[6]

- Steele

- Stegaurach

- Tangermünde

- Tauberbischofsheim

- Tennstedt

- Thangelstedt

- Thingau

- Thorr

- Thüngen

- Tilleda

- Treben

- Trebur

- Treis

- Trier

- Trifels

- Überlingen

- Ulm

- Vaihingen an der Enz

- Velden

- Verden

- Vilich

- Villmar

- Vlatten

- Völklingen

- Vreden

- Wadgassen

- Wahren

- Waiblingen

- Walbeck

- Waldsassen

- Walldorf

- Wallhausen

- Wallhausen

- Wechmar

- Weilburg

- Weinheim

- Weinsberg

- Weisenau

- Weißenburg

- Werben

- Werden

- Werla

- Wiedenbrück

- Wiehe

- Wiesbaden

- Wiesloch

- Wildeshausen

- Wimpfen

- Winterbach

- Wölfis

- Worms

- Würzburg

- Wurzen

- Xanten

- Zeitz

- Zülpich

- Zusmarshausen

- Zutphen

See also

- Palace

- Palas

- Imperial castle (Reichsburg)

References

- Eintrag Pfalz in Duden online

- Michael Gockel: Karolingische Königshöfe am Mittelrhein. Verlag Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen, 1970.

- Die Geschichte von Kraisdorf

- Hansmartin Schwarzmaier (1983), "Die Reginswindis-Tradition von Lauffen. Königliche Politik und adelige Herrschaft am mittleren Neckar" (PDF), Zeitschrift für die Geschichte des Oberrheins/N.F. (in German), 131, ISSN 0044-2607, retrieved 2014-02-21

- Zeitschrift des Harz-Vereins für Geschichte und Altertumskunde

- Ortsteil Stallbaum

Literature

- Adolf Eggers: Der königliche Grundbesitz im 10. und beginnenden 11. Jahrhundert, H. Böhlaus Nachfolger, 1909

- Lutz Fenske: Deutsche Königspfalzen: Beiträge zu ihrer historischen und archäologischen Erforschung, Zentren herrschaftlicher Repräsentation im Hochmittelalter: Geschichte Architektur und Zeremoniell, by the Max Planck Institute of History, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1963, ISBN 3-525-36521-7, 9783525365212

- Paul Grimm: Stand und Aufgaben des archäologischen Pfalzenforschung in den Bezirken Halle und Magdeburg, Akademie-Verlag, 1961

- Günther Binding: Deutsche Königspfalzen, Von Karl dem Großen bis Friedrich II. (765–1240). Darmstadt, 1996, ISBN 3-534-12548-7.

- Alexander Thon: Barbarossaburg, Kaiserpfalz, Königspfalz oder Casimirschloss? Studien zu Relevanz und Gültigkeit des Begriffes „Pfalz“ im Hochmittelalter anhand des Beispiels (Kaisers-)Lautern. In: Kaiserslauterer Jahrbuch für pfälzische Geschichte und Volkskunde. Kaiserslautern, 1.2001, ISSN 1619-7283, pp. 109–144.

- Alexander Thon: ... ut nostrum regale palatium infra civitatem vel in burgo eorum non hedificent. Studies of relevance and validity to do with the term "Pfalz" for the research of castles of the 12th and 13th centuries in: Burgenbau im 13. Jahrhundert. pub. by the Wartburg-Gesellschaft for the research of castles and palaces along with the Germanic National Museum. Research into castles and palaces. Vol. 7. Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich, 2002, ISBN 3-422-06361-7, pp. 45–72.

- Gerhard Streich: Burg und Kirche während des deutschen Mittelalters. Untersuchungen zur Sakraltopographie von Pfalzen, Burgen und Herrensitzen, 2 Vols., published by the Constance Working Group for Medieval History, Thorbecke-Verlag, 1984, ISBN 978-3-7995-6689-6.