Caer

Caer (Welsh pronunciation: [kɑːɨr]; Old Welsh: cair or kair) is a placename element in Welsh meaning "stronghold", "fortress", or "citadel",[1] roughly equivalent to an Old English suffix (-ceaster) now variously written as -caster, -cester, and -chester.[2][3]

In modern Welsh orthography, caer is usually written as a prefix, although it was formerly—particularly in Latin—written as a separate word. The Breton equivalent is kêr, which is present in many Breton placenames as the prefix Ker-.

Etymology

The term is thought to have derived from the Brittonic *kagro- and to be cognate with cae ("field, enclosed piece of land").[4] Although stone castles were largely introduced to Wales by the invading Normans, "caer" was and remains used to describe the settlements around some of them as well. An example is the Roman fort at Caernarfon, formerly known in Welsh as Caer Seiont from its position on the Seiont; the later Edwardian castle and its community were distinguished as Caer yn ar Fon ("fort in the land opposite Anglesey").[2] However, the modern names of the Roman fort and Edwardian castle themselves are now Segontiwm or Castell Caernarfon, while the communities carry on the name caer.

Note that the term is not believed to be related to the Irish cathair ("city"), which is instead derived from Proto-Celtic *katrixs, *catarax ("fortification").[5][6]

Britain

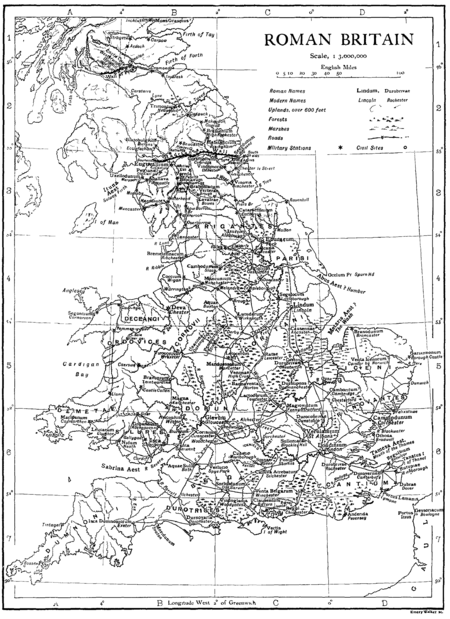

Gildas's account of the Saxon invasions of Britain claimed that there were 28 fortified Roman cities (Latin: civitas) on the island, without listing them.[8] The History of the Britons traditionally attributed to Nennius includes a list of the 28, all of which are called "caer".[7][12] Controversy exists over whether this list includes only Roman cities or a mixture of Roman cities and non-Roman settlements.[13] Some of the place names that have been proposed include:

- Cair Guorthigirn. ("Fort Vortigern": Little Doward?[10] Carmarthen?[14])

- Cair Guinntguic. ("Fort Venta": Winchester?[10] Norwich or Winwick?[11])

- Cair Mincip. ("Fort Municipium": St Albans)

- Cair Ligualid. ("Fort Luguwalos": Carlisle)

- Cair Meguaid. ("Fort Mediolanum": Meifod?[10][11] Llanfyllin?[15] Caersws?[16] in Powys)

- Cair Colun. ("Fort Colonia": Colchester?[10][11])

- Cair Ebrauc. ("Fort York": York)

- Cair Custoeint. ("Fort Constantius or Constantine": Caernarfon;[18] or poss. a Devonian hillfort[19])

- Cair Caratauc. ("Fort Rampart": Salisbury?[11] Sellack?[10])

- Cair Grauth. ("Fort Granta": Cambridge[20])

- Cair Maunguid. (Manchester?)

- Cair Lundem. ("Fort Londinium": London[21])

- Cair Ceint. ("Fort Kent": Canterbury)

- Cair Guiragon. ("Fort Weorgoran": Worcester)

- Cair Peris. (Porchester?[11][10] Builth Wells?[10])

- Cair Daun. ("Fort Don": Doncaster)

- Cair Legion. ("Fort Legion": Chester)

- Cair Guricon. (Warwick?[11] Wroxeter?[10])

- Cair Segeint. ("Fort Seiont": Caernarfon;[10] or poss. Silchester[11])

- Cair Legeion Guar Usic. ("Fort Legion on the Usk": Caerleon-upon-Usk)

- Cair Guent. ("Fort Venta": Caerwent[10] or Winchester[11])

- Cair Brithon. ("Fort of the Britons": Dumbarton in Strathclyde[10][22])

- Cair Lerion. ("Fort Leir": Leicester)

- Cair Draitou. (Drayton?[11] Dunster?[10])

- Cair 'Pensa vel Coyt'. ("Fort Penselwood":[23] Exeter?[11] Ilchester?[10])

- Cair Urnarc. (Wroxeter?[11] Dorchester?[10])

- Cair Celemion. (Camalet?[25] Silchester?[10])

- Cair Luit Coyt. ("Fort Grey Wood": Wall[28])

Wales

Examples in modern Wales include:

- Caerleon (Caerllion, "Fort Legion")

- Caernarfon ("Fort Arfon")

- Caerphilly (Caerffili, "Fort Ffili")

- Caerwent ("Fort Venta")

- Cardiff (Caerdydd, "Fort Taf")

- Holyhead (Caergybi, "Fort Cybi")

England

Modern Welsh exonyms for English cities include:

- Cambridge (Caergrawnt, "Fort Granta")

- Canterbury (Caergaint, "Fort Kent")

- Carlisle (Caerliwelydd, "Fort Luguwalos")

- Chichester (Caerfuddai )

- Gloucester (Caerloyw )

- Exeter (Caerwysg, "Fort Usk")

- Lancaster (Caerhirfryn )

- Leicester (Caerlŷr, "Fort Leir")

- Lichfield (Caerlwytgoed, "Fort Grey Wood")

- Salisbury (Caersallog )

- Winchester (Caerwynt )

- Worcester (Caerwrangon )

Scotland

Southern Scotland, the former Old North of the Romano-Britons, contains many modern placenames with variant forms of caer, including:

- Carriden ("Fort Eidyn")

- Cramond ("Fort Almond")

- Caerlanrig ("Fort Clearing")

- Carfrae ("Fort Brae")

- Cardrona ("Fort Ronan")

- Carruthers

- Kirkcaldy ("place of the hard fort" or "place of Caled’s fort")[29]

In fiction

- Caer Bronach and Caer Oswin from Dragon Age: Inquisition

- Caer Cadarn from The Warlord Chronicles - set in Cadbury Castle, Somerset according to the author's note in The Winter King.

- Caer Dallben from The Chronicles of Prydain series

- Caer Llyr and Caer Secaire from The Dark World

- Caer Siorai from Death's Gambit

- Cair Andros from The Lord of the Rings

- Cair Paravel from The Chronicles of Narnia

- Kaer Morhen from The Witcher series

- Caer Darrow from World of Warcraft

- Kêr-Is (Ys), of Breton legend

See also

- Gaer (disambiguation)

- Welsh toponymy

References

- Carlisle, Nicholas. Topographical Dictionary of the Dominion of Wales, "Glossary", p. xxx. W. Bulmer & Co. (London), 1811.

- Allen, Grant. "Casters and Chesters" in The Cornhill Magazine, Vol. XLV, pp. 419 ff. Smith, Elder, & Co. (London), 1882.

- More precisely, these English placename elements derive from Latin castrum ("fortified post") and its plural form castra ("military camp"), making them the more precise equivalent of the Welsh castell.

- Geiriadur Prifysgol Cymru, vol. 1, p. 384.

- Ebel, Hermann Wilhelm (April 6, 2001). "The Development of Celtic Linguistics, 1850-1900: Celtic studies". Taylor & Francis – via Google Books.

- Stifter, David (June 12, 2006). "Sengoidelc: Old Irish for Beginners". Syracuse University Press – via Google Books.

- "JTK". "Civitas" in Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia, Vol. I, p. 451. ABC-CLIO (Sta. Barbara), 2006.

- De Excidio Britanniae, § 3. (in Latin) Cited in the "Civitas" entry of Celtic Culture.[7]

- Nennius (attrib.). Theodor Mommsen (ed.). Historia Brittonum, VI. Composed after AD 830. (in Latin) Hosted at Latin Wikisource.

- Ford, David Nash. "The 28 Cities of Britain Archived 2016-04-15 at the Wayback Machine" at Britannia. 2000.

- Newman, John Henry & al. Lives of the English Saints: St. German, Bishop of Auxerre, Ch. X: "Britain in 429, A. D.", p. 92. Archived 2016-03-21 at the Wayback Machine James Toovey (London), 1844.

- Latin names according to Mommsen's edition of Nennius,[9] translations and modern equivalents according to Ford,[10] Ussher,[11] or as otherwise noted.

- Breeze, Andrew. "Historia Brittonum" and Britain’s Twenty-Eight Cities at Journal of Literary Onomastics. 2016.

- Veprauskas, Michael. "The Problem of Caer Guorthigirn" at Vortigern Studies. 1998.

- Williams, Robert. "A History of the Parish of Llanfyllin" in Collections Historical & Archaeological Relating to Montgomeryshire, Vol. III, p. 59. J. Russell Smith (London), 1870.

- Roman Britain Organisation. "Mediomanum?" at Roman Britain Archived 2007-04-01 at the Wayback Machine. 2010.

- On page 20 of Stevenson's 1838 edition of Nennius's works.

- Bishop Ussher cites another passage in Nennius:[17] "Here, says Nennius, Constantius the Emperor (the father probably of Constantine the Great) died; that is, near the town of Cair Segeint, or Custoient, in Carnarvonshire". Nennius stated that the emperor's inscribed tomb was still present in his day.[11] Ford credits this to Constantine, son of Saint Elen.[10]

- Per Ford, who ascribed Nennius's "Caer-Custoeint" to one of the Dumnonian kings named Constantine.[10]

- Although note that Bishop Ussher ascribed this to the Cambridge in Gloucestershire.[11]

- Both Ussher and Ford use the transcription Lundein; with regard to Mommsen, note the similarity with Lindum, the Roman name for present-day Lincoln, and the generic name *Lindon, "lake".

- Bishop Ussher argued for Bristol.[11]

- Coit is Welsh for "woods" or "forest". Ford takes the name as a single construction "Caer-Pensa-Uel-Coyt" ("Fort Penselwood"), while Mommsen and Ussher treat vel as the Latin word for or: "Cair Pensa or Coyt".[9][11]

- Cited in Frank Reno's The Historic King Arthur: Authenticating the Celtic Hero of Post-Roman Britain, Ch. 7: "Camelot and Tintagel", p. 201.

- Usser,[11] following John Leland.[24]

- In Academy, Vol. XXX, Oct. 1886.

- Wolcott, Darrell. "Glast and the Glastening". Center for the Studies of Ancient Wales (Jefferson), 2010.

- Henry of Huntington previously ascribed it to Lincoln, which was followed until the 19th century, when Bradley placed it at Lichfield,[26] thinking it to be the Roman Letocetum.[27] Instead, excavations have shown that Letocetum was located at nearby Wall instead.[10]

- "Fife Place-name Data :: Kirkcaldy". fife-placenames.glasgow.ac.uk.