Beijing Legation Quarter

The Beijing Legation Quarter was the area in Beijing, China where a number of foreign legations were located between 1861 and 1959. In the Chinese language, the area is known as Dong Jiaomin Xiang (simplified Chinese: 东交民巷; traditional Chinese: 東交民巷; pinyin: Dōng Jiāomín Xiàng), which is the name of the hutong (lane or small street) through the area. It is located in the Dongcheng District, immediately to the east of Tiananmen Square. The city of Beijing was commonly called Peking by Europeans and Americans until the 1950s.

The Legation Quarter was the location of the 55-day siege of the International Legations, which took place during the Boxer Rebellion of 1900. After the Boxer Rebellion, the Legation Quarter was under the jurisdiction of foreign countries with diplomatic legations (later most commonly called "embassies") in the quarter. The foreign residents were exempt from Chinese law. The Legation Quarter attracted many diplomats, soldiers, scholars, artists, tourists, and Sinophiles. World War II effectively ended the special status of the Legation Quarter, and with the Great Leap Forward and other events in communist China most of the European-style buildings of the Legation Quarter were destroyed.

Origins and description

During the Yuan dynasty, the street was known as the Dong Jiangmi Xiang (simplified Chinese: 东江米巷; traditional Chinese: 東江米巷; pinyin: Dōng Jiāngmĭ Xiàng), or "East River-Rice Lane". It was the location of the tax office and customs authorities, because of its proximity to the Grand Canal, 30 kilometres (19 mi) east, by which rice and grains arrived in Beijing from the south. During the Ming dynasty, a number of ministries relocated into the area, including the Ministry of Rites, which was in charge of diplomatic matters. Several hostels were built for tributary missions from Vietnam, Mongolia, Korea and Burma.

The Chinese government had long denied the European countries and the United States a diplomatic presence in the imperial capital of Beijing. However, the Convention of Peking after China's defeat in the Second Opium War of 1856–60, required the Qing Dynasty government to permit diplomatic representatives to live in Beijing. The area around Dong Jiangmi Xiang was opened for the establishment of foreign legations.[1] The Zongli Yamen was established as a foreign office of the Qing Dynasty to deal with the foreigners.

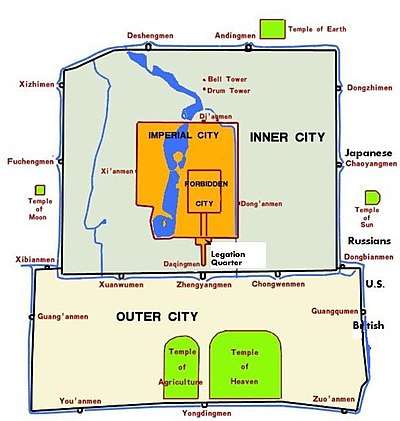

In 1861, the British legation was established in the residence of Prince Chun, the French legation was established in the residence of Prince An, and the Russian legation was established in the existing Russian quarters of the Orthodox Church. In 1862, the American legation was established in the home of Dr. Samuel Wells Williams, an American who was appointed to head the U.S. legation. Other countries also soon followed suit.[2] By 1900 there were 11 legations in the Legation Quarter: the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Japan, Russia, Italy, Spain, Austria, Belgium, Netherlands, and the United States.[3]

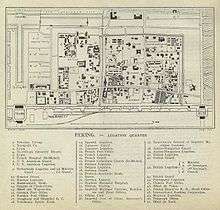

The Legation Quarter was rectangular in shape, approximately 1,300 metres (4,300 ft) east to west and 700 metres (2,300 ft) north to south. The southern boundary was the city wall of Beijing, commonly called the Tartar Wall. The Tartar wall was massive, 13 metres (43 ft) high and 13 metres (43 ft) thick on top. The northern boundary was near the wall around the Imperial City. On the east the Legation Quarter was bordered near the Hata gate, the Chongwenmen in pinyin, and on the west near the Chien or Zhengyang gate, the Qianmen in pinyin.[4] Legation Street, now called Dongjiaomin Xiang (East Foreign Residents Alley), bisected the Legation Quarter from east to west. The Imperial Canal, described as "noxious" ran through the center of the quarter from north to south, exiting the legation quarter through a watergate beneath the Tartar Wall.[5] The quarter had its own postal system and taxes.[6]

In the late 19th century the eleven foreign delegations were scattered among modest Chinese houses and opulent palaces inhabited by Manchu princes. However, in 1860, Peking was "in a wretched state of dilapidation and ruin, and scarcely one of their palatial buildings is not falling into decay."[7] Legation Street in 1900 was still "a straggling unpaved slum of a thoroughfare, along which one occasionally sees a European picking his way between the ruts and puddles with the donkeys and camels."[8] A number of foreign enterprises in addition to the legations had been established in the quarter, including two large stores catering to Europeans, two foreign banks, the Jardine Matheson trading house, the Imperial Maritime Customs offices, managed by an Englishman, Robert Hart, and the Swiss-run Hotel de Pekin.[9]

The Boxer Rebellion

During the Boxer Rebellion in 1900, the Legation Quarter was besieged by Boxers and the Qing army for 55 days. The Siege of the Legations was lifted on August 14 by a multi-national army, the Eight-Nation Alliance, which marched to Beijing from the coast and defeated the Chinese army in a series of battles, including the Battle of Peking. Of the 900 foreign nationals, including 400 soldiers, who took refuge in the Legation Quarter, 55 soldiers and 13 civilians were killed. Beijing was occupied for more than one year by the foreign armies.[10]

The Boxer Protocol of 1901 officially ended the Boxer Rebellion. China was forced to pay a large indemnity to the foreign powers. Article VII of the Protocol said that "the quarter occupied by the legations shall be considered as one specially reserved for their use and placed under their exclusive control, in which Chinese shall not have the right to reside and which may be made defensible." The Protocol also established the exact boundaries of the Legation Quarter.[11]

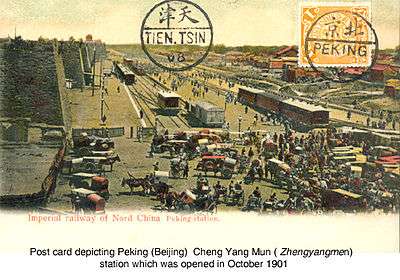

Most of the buildings, Chinese and foreign-owned, in the Legation Quarter were damaged or destroyed during the Boxer Rebellion. The area was quickly rebuilt and became more European. In 1902, legations had been rebuilt and expanded, Legation Street had been paved, and the Peking-Mukden Railway from Tianjin had been extended to the Chien (Zhengyang) gate, just across the Tartar Wall from the Legation Quarter.[12] Foreign soldiers patrolled the streets of the Legation Quarter, and Chinese houses and property had been expropriated or purchased. A wall had been constructed around the Legation Quarter and outside the wall a grassy area, a glacis, gave the soldiers a field of visibility to warn them of advancing trouble—and also isolating them from the Chinese.[13]

The "golden era"

In the years after the Boxer Rebellion, foreign influence increased in Beijing, a conservative bastion of China. Missionaries, tourists, artists, soldiers, and businessmen came in larger numbers to visit or reside in the Legation Quarter. The "place just crawls" with "globetrotters" said a British diplomat in 1907. The ubiquitous Protestant missionaries, mindful of the anti-missionary and anti-Christian fervor of the Boxers, began to turn away from proselytizing, and more toward education, health, and women's issues in attempting to accelerate a century of very slow progress in achieving their goal of making China into a Christian nation.[14] A few foreign businessmen came to Peking and many foreign enterprises were located in the Legation Quarter, but Peking never became a mercantile center for foreign companies comparable to Shanghai and other Treaty Ports. The foreign population in Beijing was never more than two to three thousand people (not counting foreign soldiers), compared to the 60,000 non-Chinese who lived in Shanghai in 1930. (The American civilians resident in Beijing in 1937 numbered about 700.) Rather the population that Beijing attracted included, in addition to the diplomats working in the Legations and the soldiers guarding them, a sizable number of scholars, artists, and aesthetes, especially in the early 1930s. They were attracted by the ancient Chinese culture preserved in Beijing and leisurely living for very little money.[15]

For the Europeans or Americans visiting or living in the Legation Quarter, it was a familiar environment of paved streets, western architecture, lawns, trees, social clubs, bars and restaurants. Chinese servants of foreigners were allowed to live in the Legation quarter, but others could only enter with temporary passes from guards at every entrance to the Legation Quarter. It was a leisurely life for diplomats, their guards, and other foreigners, who had legions of servants and for whom life consisted of a "perpetual merry-go round of parties....One hardly saw any Chinese guests among the crowd....Riding and horse racing", and a "delightful immorality" prevailed.[16]

However, in the opinion of many, the "latent hatred of the foreigner" by the Chinese was in no way diminished. Relationships between foreigners and Chinese were mostly superficial, with few successful efforts to "bridge the gap which separates white & yellow."[17]

The Legation Guards

The Boxer Protocol gave the legations the right to station soldiers in the Legation Quarter. The United States usually had the largest contingent, consisting of marines after 1905. at the end of World War I in 1918, the U.S. guard contingent consisted of 222 men. The Japanese had 180 men and the British 102. Other countries had smaller numbers of soldiers. Those numbers for the U.S. gradually increased to reach a total of 567 Marines on December 31, 1937, the increase being due to increased political instability in north China. The legation guards had the task of defending the Legation Quarter from a repetition of the Boxer Rebellion, and also securing the roads and railroad from Beijing to Tianjin, the line of escape from China for the foreigners if worse came to worse.[18]

A departing Marine in the late 1920s described the leisurely life of the legation guards. You "get the afternoons off....You don't make your own bed; you don't shine your own shoes; you don't fill your own canteen; you don't shave yourself; the Chink coolies do it for you. You get waited on hand and foot." He added however, that he was leaving because China was not a "white man's country."[19]

World War II

The people of the Legation Quarter suffered a series of political shocks: the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1911 to Yuan Shikai, the warlord era from his death in 1916 until 1928 when Chiang Kai Shek and the Republic of China army consolidated its rule over China, and the growing influence of an increasingly aggressive Japan. The capital was moved to Nanjing in 1928 which reduced the political importance of Beijing. Beijing (northern capital) became Beiping (northern peace). The diplomats in Beiping, enjoying the delights of the Legation Quarter, resisted moving their legations to Nanjing, commuting instead between the two cities, a trip that took days of difficult travel.[20]

Japan took over the Chinese province of Manchuria in 1931, engaged in a brief war with Chinese forces near Shanghai in 1932, and steadily encroached on the area around Beijing. World War II in East Asia properly began on July 7, 1937 when Japanese and Chinese soldiers clashed in the Marco Polo Bridge Incident. The Marco Polo Bridge was about 20 kilometres (12 mi) west of the Legation Quarter. More fighting ensued and on August 8, the victorious Japanese army marched into Beijing. Foreigners observed the fighting outside Beijing from the roof of the Peking Hotel. The legations ordered all their citizens to take refuge in the Legation Quarter. A "polyglot assortment" of people showed up of "missionaries, Eurasians, Chinese and Russian wives of Americans" and dozens of White Russians at the American Legation, by then called an Embassy. The refugees soon returned to their homes as the fighting ceased with the Japanese in firm control. The consequence of the Japanese conquest was that foreign residents of the Legation Quarter began to leave China, and the number of legation guards was drawn down.[21] The final departure of American Marines from Beijing and northern China was to be December 10, 1941.[22]

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 8, 1941 (Asian time) foiled the planned evacuation. The 203 American Marine guards remaining in the Legation Quarter, Tianjin, and Chinwangtao surrendered to the Japanese and became prisoners of war for the remainder of World War II.[23] The civilian foreigners remaining in Beijing were relatively undisturbed until February 1943 when they received a letter ordering them to assemble in the (former) American legation to be transported by railroad to Weihsien Civilian Assembly Center, 320 kilometres (200 mi) south of Beijing. The group, ranging in age from six months to 85 years old and including many missionaries, doctors, scholars, and businessmen, were allowed to take only what they could carry and were marched past Chinese crowds assembled to see the humiliation of the foreigners. The foreign population of Beijing was interned in Weihsien until the end of World War II.[24]

The People's Republic

After World War II, some of the internees at Weihsien returned to Beijing and attempted to re-establish pre-war institutions such as the Peking Union Medical College. Peking was occupied by American soldiers in late 1945 and 1946, but there was a steady outflow of foreign residents from Beijing afterwards as the civil war between nationalists and the Chinese communists moved ever closer. On January 23, 1949 the nationalist forces in Beijing surrendered to the communists.[25]

At the time of the victory of the People's Republic of China (1949), a number of foreign legations were still situated in the legation area. The missions of East Germany, Hungary, Burma and the United Kingdom were all located in the Legation Quarter in the 1950s, but after 1959 foreign missions were relocated to Sanlitun outside the old city walls.

However, the area suffered much vandalism during the Cultural Revolution. More damage was inflicted since the 1980s due to Beijing's redevelopment. Several buildings, such as the former HSBC building, were demolished for road expansion. Some buildings are occupied by government institutions. A number of modern high-rise buildings have also been built, dramatically changing the area's appearance. Nevertheless, as Beijing's most significant collection of Western-style buildings, the area is a tourist destination, is protected by municipal artifact preservation orders, and now features several fine dining restaurants, including one located in the former American legation,[26] and retail shops.

White Russians

An exception to the privileged status of the foreigners in the Legation Quarter were the "White Russians" who flooded into China after World War I and into the early 1920s after their defeat in the Russian Civil War in the Soviet Union. Most of the Russians went to Manchuria and treaty ports such as Shanghai, but a few ended up in Beijing. In 1924, the Chinese government recognized the government of the Soviet Union and the majority of White Russians in China who refused to become Soviet citizens were rendered stateless, thus subject to Chinese law unlike other Europeans, Americans, and Japanese living in China who enjoyed the principles of extraterritoriality. Nor were White Russians born in China eligible to be Chinese citizens.[27]

Although some of the White Russians arrived with their fortunes intact, most were penniless and due to ethnic prejudices and their inability to speak English were unable to find jobs. To support themselves and their families, many of the younger women became prostitutes or taxi dancers. They were popular with both foreign men, there being a shortage of foreign women, and Chinese men. A League of Nations survey in Shanghai in 1935 found that 22% of Russian women between 16 and 45 years of age were engaging in prostitution to some extent.[28] The percentage in Beijing may have been higher than Shanghai as economic opportunities were more limited.

The White Russian women mostly worked in the "Badlands" area adjoining the Legation Quarter on the east, centered on Chuanban Hutong (alley). The American explorer Roy Chapman Andrews said he frequented the "cafes of somewhat dubious reputation" with the explorer Sven Hedin and scientist Davidson Black to "have scrambled eggs and dance with the Russian girls."[29] An Italian diplomat condemned the White Russians: "The prestige of the white face fell precipitously when Chinese could possess a white woman for a dollar or less, and Russian officers in tattered uniforms begged at the doors of Chinese theaters."[30]

See also

Notes

- Chia Chen Chu (1944), "Diplomatic Quarter in Peiping," A Dissertation submitted to the University of Ottawa, pp. 5-8

- Chia Chen Chu, p. 8

- "How to visit Dong Jiao Min Xiang", https://www.tour-beijing.com/blog/beijing-travel/how-to-visit-dong-jiao-min-xiang, accessed 5 Jan 2018

- Calculated from File:Peking legation quarter.jpg.

- Thompson, Larry Clinton (2009), William Scott Ament and the Boxer Rebellion, Jefferson, NC: McFarland Publishing Co., pp. 30, 36-38

- Lewis, Simon (31 October 2013). The Rough Guide to Beijing. ISBN 9781409351726.

- Cranmer-Byng, J. L. (1962), "The Old British Legation at Peking, 1860-1959," Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch, pp. 63-64. Downloaded from JSTOR.

- Thompson, pp. 36-37

- Preston, Diana (2000), The Boxer Rebellion, New York: Berkley Books, p. 10

- Thompson, pp. 83-85, 173, 183-184

- "Settlement of Matters relating to the Boxer Rebellion (Boxer Protocol)",https://www.loc.gov/law/help/us-treaties/bevans/m-ust000001-0302.pdf, accessed 12 Jan 2018

- Thompson, p. 215

- Boyd, Julia (2012), A Dance with the Dragon, London: I. B. Tauris, p. 39

- Boyd, pp. 60-67

- Letcher, pp. 17-20; "Tales of Old China: Census and Population", http://www.talesofoldchina.com/shanghai/business/census-and-population Archived 2018-01-14 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 13 Jan 2018; Boyd, p. 181

- Boyd, pp. Xviii, 65, 125

- Boyd, p. 67, 107

- Letcher, pp. 3-4, 20; "The China Marines: Peking", http://www.chinamarine.com/Peking.aspx%5B%5D, accessed 19 Jan 2018; Letcher, p, 20

- Letcher, p. x

- Boyd, pp. 150-152

- Boyd, p. 192

- http://chinamarine.org/Peking.aspx

- http://www.northchinamarines.com/index.htm

- Gilkey, Langdon (1966), Shangtung Compound, New York: Harper & Row, pp 1-4

- Boyd, pp. 210-219

- Lewis, Simon (31 October 2013). The Rough Guide to Beijing. ISBN 9781409351726.

- Shen Yuanfang and Edwards, Penny (2002), "The Harbin Connection: Russians from China", Beyond China, Canberrra: Australian National University, pp. 75-87, http://maramoustafine.com/wp-content/uploads/the-harbin-connection-anu-2004.pdf, accessed 14 Jan 2018

- Ristaino, Marcia Reynders (2001), Port of last resort : the diaspora communities of Shanghai, Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2001, page 94]

- Andrews, Roy Chapman (1943), Under a Lucky Star, New York: Viking Press, p.164

- Boyd, 138

References

- Moser, Michael J., and Yeone Wei-chih Moser. Foreigners within the Gates: The Legations at Peking. Hong Kong, New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Beijing Legation Quarter. |