Villa Poppaea

The Villa Poppaea is an ancient luxurious Roman seaside villa (villa maritima) located in Torre Annunziata between Naples and Sorrento, in Southern Italy. It is also called the Villa Oplontis or Oplontis Villa A.[1] as it was situated in the ancient Roman town of Oplontis.

The Villa Poppaea as seen from the garden in front | |

| Alternative name | Villa Oplontis, Villa A |

|---|---|

| Location | Torre Annunziata, Province of Naples, Campania, Italy |

| Coordinates | 40°45′26″N 14°27′9″E |

| Type | Roman villa |

| Part of | Oplontis |

| Site notes | |

| Management | Soprintendenza Speciale per i Beni Archeologici di Napoli e Pompei |

| Website | Oplontis (in Italian and English) |

| Official name | Archaeological Areas of Pompeii, Herculaneum, and Torre Annunziata |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iii, iv, v |

| Designated | 1997 (21st session) |

| Reference no. | 829-006 |

| Region | Europe and North America |

It was buried and preserved in the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD, like the nearby cities of Herculaneum and Pompeii, about 10 m (33 ft) below modern ground level.

The quality of the decorations and construction suggests that it was owned by the Emperor Nero, and a pottery sherd bearing the name of a freedman of Poppaea Sabina, the second wife of the emperor Nero was found at the site, which suggests the villa may have been her residence when she was away from Rome and which gives it its popular name.[2]

It was sumptuously decorated with fine works of art.[3] Its marble columns and capitals mark it out as being especially luxurious compared with others in this region that usually had stuccoed brick columns.

Many artifacts from Oplontis are preserved in the Naples National Archaeological Museum.

Parts of the villa lying under modern structures remain unexcavated.

Site

It was one of the luxury villas built along the entire coast of the Gulf of Naples in the Roman period, such that Strabo wrote:

- "The whole gulf is quilted by cities, buildings, plantations, so united to each other, that they seem to be a single metropolis."[4]

The villa was originally built on a shelf 14m above sea level and above the sea shore giving it a beautiful view over the Bay of Naples. It is known that other buildings lay near the shore line below, possibly baths, and at Lido Azzurro nearby the ancient coastline has been found along with traces of Roman baths that may have been public.[5]

Construction

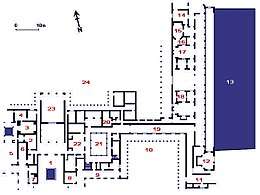

The villa was first built in the 50s BC and then enlarged in stages. The oldest part of the house centres around the atrium.[2] During the remodeling, the house was extended to the east, with the addition of various reception and service rooms, gardens and a large swimming pool.[6]

This grandiose maritime villa is characterized by “rituals of reception and leisure” through both its physical space and its decoration.[7]

Its original core comprised an atrium, public dining and other reception rooms, and smaller rooms. A kitchen, baths (later rebuilt for entertainment), a lararium, and a peristyle comprised the service area. Workrooms and dormitories on the upper floor for slaves, and a latrine and baths on the ground floor surrounded this peristyle.

It was extended in the age of Claudius (AD 41-54) when peristyles with colonnaded porticoes extended out from the building's core, framing formal gardens.

The east garden had an immense swimming pool in the centre bordered on the south and east by trees.

Some 40 marble sculptures of extraordinary beauty were found, forming one of the most extensive collections of statues, busts and other marble ornaments known in the entire region.[8] Among these was a group of centaurs and centauresses found in the west portico facing the north garden. Many of them also served as fountains and were intended to surround the pool but were found away from their proper position.

The Villa's earliest frescoes are some of the best examples of the illusionistic Second Style, while later renovations and additions are marked by comparably high-quality paintings of the Third and Fourth Styles. Mosaic floor pavements of varying types occur throughout the Villa.

Like everywhere else in the region the villa was damaged in the earthquake of AD 62 and renovation and repairs were still being made until its last moments as, for example, some of the columns were found dissembled and garden sculptures away from their proper location indicates.[9]

Frescoes

Like many of the frescoes that were preserved due to the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, those decorating the walls of the Villa Poppaea are striking both in form and in color. Many of the frescoes are in the “Second Style” (also called the Architectural Style) of ancient Roman painting, dating to ca. 90-25 BC as classified in 1899 by August Mau.[10] Details include feigned architectural features such as trompe-l'œil windows, doors, and painted columns.

Frescoes in the caldarium depicting Hercules in the Garden of the Hesperides are painted in the "Third Style" (also called the Ornate Style) dating to ca. 25 BC-40 AD according to Mau. Attention to realistic perspective is abandoned in favor of flatness and elongated architectural forms which “form a kind of shrine" around a central scene, which is often mythological.[11]

Immediately to the west of the triclinium is a large oecus, which was the main living room of a Roman house. Like the caldarium frescoes, the room is also painted in the Second Style. The east wall includes some wonderful details such as a theatre mask and peacock.[12]

Much attention has been paid to the allusions to stage painting (scenae frons) in the Villa Poppaea frescoes, particularly those in Room 23.[13]

Gardens

By 1993, 13 gardens had been discovered, among which was a peristyle garden in the original portion of the villa. A large shade tree next to a fountain was found, and also a sundial, a rake, a hoe, and a hook.[14]

Another garden in the grounds, this one enclosed, featured wall paintings of plants and birds, and evidence of fruit trees growing in the garden’s corners. Two courtyard gardens also featured wall paintings. A large park-like garden extends from the back of the villa. Cavities that had once housed the roots of large trees were discovered and shown to be plane trees.

Also found were the remains of tree stumps which were shown be olives.

Other trees at the Villa Poppaea were also identified, including lemon and oleander; a carbonized apple found on the site indicates the former presence of apple trees. Modern-day replanting of the Villa’s gardens was undertaken only after the gardens’ original plant types and location were known.[15]

Rediscovery and excavation history

The Villa of Poppaea was first discovered in the eighteenth century during the construction of the Sarno aqueduct which cut through the centre of the villa [6], but no recognition of the site was made. In 1839 a brief exploration of the site was undertaken by Bourbon excavators using the tunnelling technique employed at Herculaneum, uncovering part of the peristyle and garden area[16] and removing several paintings.[1]

Official excavations were done from 1964 until the mid-1980s, at which point the site was excavated to its current level. It was during this final round of excavations that the massive swimming pool, measuring 60 by 17 metres, was unearthed. The villa’s southernmost portions have been left unexcavated because of the physical limitations of the complex, which has been compromised by its position beneath the modern city of Torre Annunziata and the Sarno aqueduct.[2]

- Portico of piscina

.jpg) cast of wooden shutters

cast of wooden shutters kitchen

kitchen- Garden north of atrium

Nearby villa

Nearby is the so-called Villa of L. Crassius Tertius,[17] partially excavated between 1974 and 1991. In contrast to the sumptuously decorated Villa Poppaea, the neighbouring villa is a rustic, two-story structure with many rooms left unplastered and with tamped earth floors.

This villa was not deserted at the time of the eruption: the remains of 54 people were recovered in one of the rooms of the villa, perishing in the surge that hit Oplontis. With the victims were found many of their belongings, including fine jewelry, silverware, and coins in the amount of 10,000 sesterces, the second largest by value found in the Vesuvian region after that of Boscoreale.[18]

Some of the rooms seem to have been used for manufacturing, and others were storerooms, while the upper floor contained the living quarters of the house. These circumstances, along with more than 400 amphorae recovered in the excavations, indicate the property was devoted to the production of wine, oil, and agricultural goods. The discovery of a series of weights seems to confirm this theory; a bronze seal found at the site preserved the name of Lucius Crassius Tertius, apparently its last owner.

References

- Coarelli 2002, p. 360.

- Coarelli 2002, p. 365.

- Oplontis. Villa di Poppea or Villa of Poppea or Villa Poppaea or Oplontis Villa A. https://www.pompeiiinpictures.com/pompeiiinpictures/VF/Villa_055%20Oplontis%20Villa%20of%20Poppea%20p29.htm

- Strabo Geography 5.4.8

- Michael L. Thomas and John R. Clarke, “Water Features, the Atrium, and the Coastal Setting of Oplontis Villa A at Torre Annunziata,” Journal of Roman Archaeology 24 (2011): 378–381.

- Clarke 1991, p. 22.

- Clarke 1991, p. 23.

- https://brunelleschi.imss.fi.it/giardinoantico/egar.asp?c=24027&k=24013&rif=24020

- Stefano de Caro, Ancient Roman Villa Gardens, Dumbarton Oaks Colloquium on the History of Landscape Architecture.

- Berry 2007, p. 171.

- Berry 2007, p. 170.

- Wallace-Hadrill 1994, p. 27.

- Wallace-Hadrill 1994, p. 27; Coarelli 2002, p. 372; Clarke 1991, p. 117.

- Jashemski 1993, p. 295.

- Bowe 2004.

- MacDougall 1987, p. 79.

- Villa of L. Crassius Tertius, sites.google.com

- Civale 2003, p. 73–74.

Sources

- Berry, Joanne (2007). The Complete Pompey. New York City; New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05150-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bowe, Patrick (2004). Gardens Of The Roman World. Los Angeles, California: J. Paul Getty Museum. ISBN 978-0-7112-2387-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Civale, Anna (2003). "Oplontis". In Guzzo, Pier Giovanni (ed.). Tales from an Eruption: Pompeii, Herculaneum, Oplontis. Milan: Electa. pp. 72–79. ISBN 978-88-370-2363-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clarke, John R. (1991). The Houses of Roman Italy, 100 B.C.–A.D. 250: Ritual, Space, and Decoration. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-08429-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Coarelli, Filippo, ed. (2002). Pompeii. Translated by Patricia A. Cockram. New York City, New York: Riverside Book Company. ISBN 978-1-878351-59-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jashemski, Wilhelmina Mary Feemster (1979). The Gardens of Pompeii: Herculaneum and the Villas Destroyed by Vesuvius. 1. New Rochelle: New York: Caratzas Brothers. ISBN 978-0-89241-096-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ——— (1993). The Gardens of Pompeii: Herculaneum and the Villas Destroyed by Vesuvius. 2. New Rochelle: New York: Caratzas Brothers. ISBN 978-0-89241-125-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- MacDougall, Elisabeth B., ed. (1987). Ancient Roman Villa Gardens. Dumbarton Oaks Colloquia on the History of Landscape Architecture. 10. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. ISBN 978-0-88402-162-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wallace-Hadrill, Andrew (1994). Houses and Society in Pompeii and Herculaneum. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02909-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Aurelius Victor, Book of the Caesars 5

- Ling, Roger. Roman Painting. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

- Maiuri, Amedeo. Pompeii. Novara: Instituto Geografico de Agostini, 1957.

- __. Herculaneum. Roma: Istituto Poligrafico dello Stato, Libreria dello Stato, 1945.

- Mau, August and Francis Willey Kelsey. Pompeii: Its Life and Art. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1899.

- Suetonius, Life of Nero

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Villa Poppaea (Torre Annunziata). |

- Official website (in Italian and English)

- The Oplontis Project

- Triclinium Villa di Poppea

- AD79 destruction and Re-discovery Oplontis: Villa di Poppea

- Romano-Campanian Wall-Painting (English, Italian, Spanish and French introduction)

- Dumbarton Oaks: Garden Archaeology

- The Villa at Oplontis, Skenographia Project