Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany

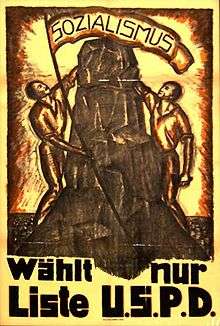

The Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (German: Unabhängige Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, USPD) was a short-lived political party in Germany during the German Empire and the Weimar Republic. The organization was established in 1917 as the result of a split of left wing members of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). The organization attempted to chart a centrist course between electorally oriented revisionism on the one hand and Bolshevism on the other. The organization was terminated in 1931 through merger with the Socialist Workers' Party of Germany (SAPD).

Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany Unabhängige Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands | |

|---|---|

| |

| Founded | 1917 |

| Dissolved | 1931 |

| Split from | Social Democratic Party of Germany |

| Succeeded by | Socialist Workers' Party of Germany |

| Newspaper | Die Freiheit |

| Membership | 120,000 (January 1918) 750,000 (Spring 1920) |

| Ideology | Centrist Marxism Democratic socialism Pacifism |

| Political position | Left-wing |

| International affiliation | International Working Union of Socialist Parties |

| Colors | Red |

Organizational history

Formation

On 21 December 1915, several SPD members in the Reichstag, the German parliament, voted against the authorization of further credits to finance World War I, an incident that emphasized existing tensions between the party's leadership and the left-wing pacifists surrounding Hugo Haase and ultimately led to the expulsion of the group from the SPD on 24 March 1916.

To be able to continue their parliamentary work, the group formed the Social Democratic Working Group (Sozialdemokratische Arbeitsgemeinschaft, SAG). Concerns from the SPD leadership and Friedrich Ebert that the SAG was intent on dividing the SPD then led to the expulsion of the SAG members from the SPD on 18 January 1917. On 6 April 1917, the USPD was founded at a conference in Gotha, with Hugo Haase as the party's first chairman. The Spartakusbund also merged into the newly founded party, but it retained relative autonomy.[1] To avoid confusion, the existing SPD was typically called the Majority Social Democratic Party of Germany (Mehrheits-SPD or MSPD, majority-SPD) from then on. Luise Zietz was one of the main agitators in favor of a split in the party in 1917.[2] She became a leader in the creation of the USPD's women's movement.[2]

Following the Januarstreik in January 1918, a strike demanding an end to the war and better food provisioning that was organized by revolutionaries affiliated with the USPD and officially supported by the party, the USPD quickly rose to about 120,000 members. Despite harsh criticism of the SPD for becoming part of the government of the newly formed German republic during the Oktoberreform, the USPD reached a settlement with the SPD as the German Revolution began and even became part of the government in the form of the Rat der Volksbeauftragten (Council of People's Deputies) which was formed on 10 November 1918 and mutually led by Ebert and Haase following the German Revolution.

However, the agreement did not last long as Haase, Wilhelm Dittmann and Emil Barth left the council again on 29 December 1918 to protest the SPD's actions during the soldier mutiny in Berlin on 23 November 1918. At the same time, the Spartakusbund, led by Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, separated from the USPD again as well to merge with other left-wing groups and form the Communist Party of Germany (Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands, KPD).

Development

During the elections for the National Assembly on 19 January 1919 from which the SPD emerged as the strongest party with 37.9% of the votes, the USPD only managed to attract 7.6%. Nevertheless, the party's strong support for the introduction of a system of councils (Räterepublik) instead of a parliamentary democracy attracted many former SPD members and in spring 1920 the USPD had grown to more than 750,000 members, managing to increase their share of votes to 17.9% during the parliamentary elections on 6 June 1920 and becoming one of the largest factions in the new Reichstag, second only to the SPD (21.7%). During that period, the SPD briefly published a newspaper, Arbeiterpost.[3]

Debate over joining the Communist International

_Der_Russische_Schwabenstreich.png)

In 1920, four delegates from the USPD (Ernst Däumig, Arthur Crispien, Walter Stoecker and Wilhelm Dittmann) attended the 2nd World Congress of the Comintern to discuss participating in the Comintern.[4] Whilst Däumig and Stoecker agreed with the International's 21 conditions of entry, Crispien and Dittmann opposed them,[4] leading to a controversial debate over joining the Comintern to break out in the USPD. Many members felt that the necessary requirements for joining would lead to a loss of the party's independence and a perceived dictate from Moscow while others, especially younger members such as Ernst Thälmann, argued that only the joining of the Comintern would allow the party to implement its socialist ideals.

Ultimately, the proposition to join the Comintern was approved at a party convention in Halle in October 1920 by 237 votes to 156,[5] with various international speakers including Julius Martov, Jean Longuet and Grigory Zinoviev. The USPD split up in the process, with both groups seeing themselves as the rightful USPD and the other one as being outcast. On 4 December 1920, the left-wing of the USPD with about 400,000 members merged into the KPD, forming the United Communist Party of Germany (Vereinigte Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands, VKPD) while the other half of the party, with about 340,000 members and including three quarters of the 81 Reichstag members, continued under the name USPD. Led by Georg Ledebour and Arthur Crispien, they advocated a parliamentary democracy. The USPD was instrumental in the creation of the 2½ International in 1921.

Move to merger

Over time, the political differences between SPD and USPD dwindled and following the assassination of foreign minister Walther Rathenau by right-wing extremists in June 1922 the two parties' factions in the Reichstag formed a common working group on 14 July 1922. Two months later on 24 September, the parties officially merged again after a joint party convention in Nürnberg, adopting the name of United Social Democratic Party of Germany (Vereinigte Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, VSPD) which was shortened again to SPD in 1924.

The USPD continued as an independent party by Georg Ledebour and Theodor Liebknecht, who refused to work with the SPD, but it never attained any significance again and merged into the Socialist Workers' Party of Germany (Sozialistische Arbeiterpartei Deutschland, SAPD) in 1931.

The party got 20,275 votes in the 1928 Reichstag election, but it won no seats.[6]

Electoral results

| Year | Leader | Votes | % | Seats | +/– |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1919 | Hugo Haase | 2,317,290 (5th) | 7.62 | 22 / 423 |

New |

| 1920 | Arthur Crispien | 5,046,813 (2nd) | 17.90 | 84 / 459 |

|

| May 1924 | Georg Ledebour Theodor Liebknecht |

235,145 (13th) | 0.79 | 0 / 472 |

|

| December 1924 | 98,842 (14th) | 0.32 | 0 / 493 |

||

| 1928 | 20,815 (25th) | 0.06 | 0 / 491 |

||

| 1930 | 11,690 (22nd) | 0.03 | 0 / 577 |

Important USPD members

Further reading

- Eric D. Weitz (1997). Creating German Communism, 1890-1990: From Popular Protests to Socialist State. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- David Priestand (2009). Red Flag: A History of Communism. New York: Grove Press.

Footnotes

- Ottokar Luban (2008). "Die Rolle der Spartakusgruppe bei der Entstehung und Entwicklung der USPD Januar 1916 bis März 1919". Jahrbuch für Forschungen zur Geschichte der Arbeiterbewegung (II).

- Joseph A. Biesinger (1 January 2006). Germany: A Reference Guide from the Renaissance to the Present. Infobase Publishing. pp. 755–. ISBN 978-0-8160-7471-6.

- Acta Universitatis Wratislaviensis: Prawo, Vol. 161. Państwowe Wydawn. Naukowe, 1988. p. 110

- Pierre Broué (2006). The German Revolution: 1917–1923. Chicago: Haymarket Books. p. 435.

- Pierre Broué (2006). The German Revolution: 1917–1923. Chicago: Haymarket Books. p. 442.

- Labour and Socialist International (1974). Kongress-Protokolle der Sozialistischen Arbeiter-Internationale – B. 3.1 Brüssel 1928. Glashütten im Taunus: D. Auvermann. p. IV. 41.