Chordate

A chordate (/ˈkɔːrdeɪt/) is an animal of the phylum Chordata. During some period of their life cycle, chordates possess a notochord, a dorsal nerve cord, pharyngeal slits, and a post-anal tail: these four anatomical features define this phylum. Chordates are also bilaterally symmetric, and have a coelom, metameric segmentation, and circulatory system.

| Chordates | |

|---|---|

| |

| Example of chordates of four subphyla of lower rank: a Siberian Tiger (Vertebrata) and a Polycarpa aurata (Tunicata), two Olfactores, as well as Ooedigera peeli (Vetulicolia) and a Branchiostoma lanceolatum (Cephalochordata). | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Subkingdom: | Eumetazoa |

| Clade: | ParaHoxozoa |

| Clade: | Bilateria |

| Clade: | Nephrozoa |

| Superphylum: | Deuterostomia |

| Phylum: | Chordata Haeckel, 1874[1][2] |

| Subgroups | |

|

And see text | |

The Chordata and Ambulacraria together form the superphylum Deuterostomia. Chordates are divided into three subphyla: Vertebrata (fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals); Tunicata or Urochordata (sea squirts, salps); and Cephalochordata (which includes lancelets). There are also extinct taxa such as the Vetulicolia. Hemichordata (which includes the acorn worms) has been presented as a fourth chordate subphylum, but now is treated as a separate phylum: hemichordates and Echinodermata form the Ambulacraria, the sister phylum of the Chordates. Of the more than 65,000 living species of chordates, about half are bony fish that are members of the superclass Pisces, class Osteichthyes.

Chordate fossils have been found from as early as the Cambrian explosion, 541 million years ago. Cladistically (phylogenetically), vertebrates – chordates with the notochord replaced by a vertebral column during development – are considered to be a subgroup of the clade Craniata, which consists of chordates with a skull. The Craniata and Tunicata compose the clade Olfactores. (See diagram under Phylogeny.)

Anatomy

Chordates form a phylum of animals that are defined by having at some stage in their lives all of the following anatomical features:[4]

- A notochord, a fairly stiff rod of cartilage that extends along the inside of the body. Among the vertebrate sub-group of chordates the notochord develops into the spine, and in wholly aquatic species this helps the animal to swim by flexing its tail.

- A dorsal neural tube. In fish and other vertebrates, this develops into the spinal cord, the main communications trunk of the nervous system.

- Pharyngeal slits. The pharynx is the part of the throat immediately behind the mouth. In fish, the slits are modified to form gills, but in some other chordates they are part of a filter-feeding system that extracts particles of food from the water in which the animals live.

- Post-anal tail. A muscular tail that extends backwards behind the anus.

- An endostyle. This is a groove in the ventral wall of the pharynx. In filter-feeding species it produces mucus to gather food particles, which helps in transporting food to the esophagus.[5] It also stores iodine, and may be a precursor of the vertebrate thyroid gland.[4]

There are soft constraints that separate chordates from certain other biological lineages, but are not part of the formal definition:

- All chordates are deuterostomes. This means that, during the embryo development stage, the anus forms before the mouth.

- All chordates are based on a bilateral body plan.[6]

- All chordates are coelomates, and have a fluid-filled body cavity called a coelom with a complete lining called peritoneum derived from mesoderm (see Brusca and Brusca).[7]

Classification

The following schema is from the fourth edition of Vertebrate Palaeontology.[8][9] The invertebrate chordate classes are from Fishes of the World.[10] While it is structured so as to reflect evolutionary relationships (similar to a cladogram), it also retains the traditional ranks used in Linnaean taxonomy.

- Phylum Chordate

- †Vetulicolia?

- Subphylum Cephalochordata (Acraniata) – (lancelets; 30 species)

- Class Leptocardii (lancelets)

- Clade Olfactores

- Subphylum Tunicata (Urochordata) – (tunicates; 3,000 species)

- Class Ascidiacea (sea squirts)

- Class Thaliacea (salps)

- Class Appendicularia (larvaceans)

- Class Sorberacea

- Subphylum Vertebrata (Craniata) (vertebrates – animals with backbones; 57,674 species)

- Superclass 'Agnatha' paraphyletic (jawless vertebrates; 100+ species)

- Class Cyclostomata

- Infraclass Myxinoidea or Myxini (hagfish; 65 species)

- Infraclass Petromyzontida or Hyperoartia (lampreys)

- Class †Conodonta

- Class †Myllokunmingiida

- Class †Pteraspidomorphi

- Class †Thelodonti

- Class †Anaspida

- Class †Cephalaspidomorphi

- Class Cyclostomata

- Infraphylum Gnathostomata (jawed vertebrates)

- Class †Placodermi (Paleozoic armoured forms; paraphyletic in relation to all other gnathostomes)

- Class Chondrichthyes (cartilaginous fish; 900+ species)

- Class †Acanthodii (Paleozoic "spiny sharks"; paraphyletic in relation to Chondrichthyes)

- Class Osteichthyes (bony fish; 30,000+ species)

- Subclass Actinopterygii (ray-finned fish; about 30,000 species)

- Subclass Sarcopterygii (lobe-finned fish: 8 species)

- Superclass Tetrapoda (four-limbed vertebrates; 28,000+ species) (The classification below follows Benton 2004, and uses a synthesis of rank-based Linnaean taxonomy and also reflects evolutionary relationships. Benton included the Superclass Tetrapoda in the Subclass Sarcopterygii in order to reflect the direct descent of tetrapods from lobe-finned fish, despite the former being assigned a higher taxonomic rank.)[11]

- Superclass 'Agnatha' paraphyletic (jawless vertebrates; 100+ species)

- Subphylum Tunicata (Urochordata) – (tunicates; 3,000 species)

Subphyla

Cephalochordata: Lancelets

Cephalochordates, one of the three subdivisions of chordates, are small, "vaguely fish-shaped" animals that lack brains, clearly defined heads and specialized sense organs.[15] These burrowing filter-feeders compose the earliest-branching chordate sub-phylum.[16][17]

Tunicata (Urochordata)

Most tunicates appear as adults in two major forms, known as "sea squirts" and salps, both of which are soft-bodied filter-feeders that lack the standard features of chordates. Sea squirts are sessile and consist mainly of water pumps and filter-feeding apparatus;[18] salps float in mid-water, feeding on plankton, and have a two-generation cycle in which one generation is solitary and the next forms chain-like colonies.[19] However, all tunicate larvae have the standard chordate features, including long, tadpole-like tails; they also have rudimentary brains, light sensors and tilt sensors.[18] The third main group of tunicates, Appendicularia (also known as Larvacea), retain tadpole-like shapes and active swimming all their lives, and were for a long time regarded as larvae of sea squirts or salps.[20] The etymology of the term Urochordata (Balfour 1881) is from the ancient Greek οὐρά (oura, "tail") + Latin chorda ("cord"), because the notochord is only found in the tail.[21] The term Tunicata (Lamarck 1816) is recognised as having precedence and is now more commonly used.[18]

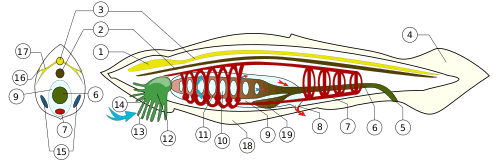

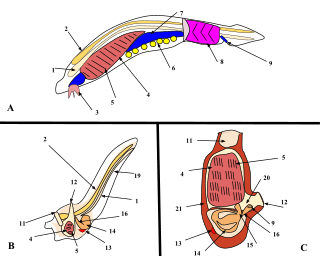

--------------------------------------------------------

1. Notochord, 2. Nerve chord, 3. Buccal cirri, 4. Pharynx, 5. Gill slit, 6. Gonad, 7. Gut, 8. V-shaped muscles, 9. Anus, 10. Inhalant syphon, 11. Exhalant syphon, 12. Heart, 13. Stomach, 14. Esophagus, 15. Intestines, 16. Tail, 17. Atrium, 18. Tunic

Craniata (Vertebrata)

Craniates all have distinct skulls. They include the hagfish, which have no vertebrae. Michael J. Benton commented that "craniates are characterized by their heads, just as chordates, or possibly all deuterostomes, are by their tails".[22]

Most craniates are vertebrates, in which the notochord is replaced by the vertebral column.[23] These consist of a series of bony or cartilaginous cylindrical vertebrae, generally with neural arches that protect the spinal cord, and with projections that link the vertebrae. However hagfish have incomplete braincases and no vertebrae, and are therefore not regarded as vertebrates,[24] but as members of the craniates, the group from which vertebrates are thought to have evolved.[25] However the cladistic exclusion of hagfish from the vertebrates is controversial, as they may be degenerate vertebrates who have lost their vertebral columns.[26]

The position of lampreys is ambiguous. They have complete braincases and rudimentary vertebrae, and therefore may be regarded as vertebrates and true fish.[27] However, molecular phylogenetics, which uses biochemical features to classify organisms, has produced both results that group them with vertebrates and others that group them with hagfish.[28] If lampreys are more closely related to the hagfish than the other vertebrates, this would suggest that they form a clade, which has been named the Cyclostomata.[29]

Phylogeny

Overview

There is still much ongoing differential (DNA sequence based) comparison research that is trying to separate out the simplest forms of chordates. As some lineages of the 90% of species that lack a backbone or notochord might have lost these structures over time, this complicates the classification of chordates. Some chordate lineages may only be found by DNA analysis, when there is no physical trace of any chordate-like structures.[31]

Attempts to work out the evolutionary relationships of the chordates have produced several hypotheses. The current consensus is that chordates are monophyletic, meaning that the Chordata include all and only the descendants of a single common ancestor, which is itself a chordate, and that craniates' nearest relatives are tunicates.

All of the earliest chordate fossils have been found in the Early Cambrian Chengjiang fauna, and include two species that are regarded as fish, which implies that they are vertebrates. Because the fossil record of early chordates is poor, only molecular phylogenetics offers a reasonable prospect of dating their emergence. However, the use of molecular phylogenetics for dating evolutionary transitions is controversial.

It has also proved difficult to produce a detailed classification within the living chordates. Attempts to produce evolutionary "family trees" shows that many of the traditional classes are paraphyletic.

| Deuterostomes |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

While this has been well known since the 19th century, an insistence on only monophyletic taxa has resulted in vertebrate classification being in a state of flux.[32]

The majority of animals more complex than jellyfish and other Cnidarians are split into two groups, the protostomes and deuterostomes, the latter of which contains chordates.[33] It seems very likely the 555 million-year-old Kimberella was a member of the protostomes.[34][35] If so, this means the protostome and deuterostome lineages must have split some time before Kimberella appeared—at least 558 million years ago, and hence well before the start of the Cambrian 541 million years ago.[33] The Ediacaran fossil Ernietta, from about 549 to 543 million years ago, may represent a deuterostome animal.[36]

Fossils of one major deuterostome group, the echinoderms (whose modern members include starfish, sea urchins and crinoids), are quite common from the start of the Cambrian, 542 million years ago.[37] The Mid Cambrian fossil Rhabdotubus johanssoni has been interpreted as a pterobranch hemichordate.[38] Opinions differ about whether the Chengjiang fauna fossil Yunnanozoon, from the earlier Cambrian, was a hemichordate or chordate.[39][40] Another fossil, Haikouella lanceolata, also from the Chengjiang fauna, is interpreted as a chordate and possibly a craniate, as it shows signs of a heart, arteries, gill filaments, a tail, a neural chord with a brain at the front end, and possibly eyes—although it also had short tentacles round its mouth.[40] Haikouichthys and Myllokunmingia, also from the Chengjiang fauna, are regarded as fish.[30][41] Pikaia, discovered much earlier (1911) but from the Mid Cambrian Burgess Shale (505 Ma), is also regarded as a primitive chordate.[42] On the other hand, fossils of early chordates are very rare, since invertebrate chordates have no bones or teeth, and only one has been reported for the rest of the Cambrian.[43]

The evolutionary relationships between the chordate groups and between chordates as a whole and their closest deuterostome relatives have been debated since 1890. Studies based on anatomical, embryological, and paleontological data have produced different "family trees". Some closely linked chordates and hemichordates, but that idea is now rejected.[5] Combining such analyses with data from a small set of ribosome RNA genes eliminated some older ideas, but opened up the possibility that tunicates (urochordates) are "basal deuterostomes", surviving members of the group from which echinoderms, hemichordates and chordates evolved.[44] Some researchers believe that, within the chordates, craniates are most closely related to cephalochordates, but there are also reasons for regarding tunicates (urochordates) as craniates' closest relatives.[5][45]

Since early chordates have left a poor fossil record, attempts have been made to calculate the key dates in their evolution by molecular phylogenetics techniques—by analyzing biochemical differences, mainly in RNA. One such study suggested that deuterostomes arose before 900 million years ago and the earliest chordates around 896 million years ago.[45] However, molecular estimates of dates often disagree with each other and with the fossil record,[45] and their assumption that the molecular clock runs at a known constant rate has been challenged.[46][47]

Traditionally, Cephalochordata and Craniata were grouped into the proposed clade "Euchordata", which would have been the sister group to Tunicata/Urochordata. More recently, Cephalochordata has been thought of as a sister group to the "Olfactores", which includes the craniates and tunicates. The matter is not yet settled.

Diagram

Phylogenetic tree of the Chordate phylum. Lines show probable evolutionary relationships, including extinct taxa, which are denoted with a dagger, †. Some are invertebrates. The positions (relationships) of the Lancelet, Tunicate, and Craniata clades are as reported[48][49][50][51]

| Chordata |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Closest nonchordate relatives

Hemichordates

Hemichordates ("half chordates") have some features similar to those of chordates: branchial openings that open into the pharynx and look rather like gill slits; stomochords, similar in composition to notochords, but running in a circle round the "collar", which is ahead of the mouth; and a dorsal nerve cord—but also a smaller ventral nerve cord.

There are two living groups of hemichordates. The solitary enteropneusts, commonly known as "acorn worms", have long proboscises and worm-like bodies with up to 200 branchial slits, are up to 2.5 metres (8.2 ft) long, and burrow though seafloor sediments. Pterobranchs are colonial animals, often less than 1 millimetre (0.039 in) long individually, whose dwellings are interconnected. Each filter feeds by means of a pair of branched tentacles, and has a short, shield-shaped proboscis. The extinct graptolites, colonial animals whose fossils look like tiny hacksaw blades, lived in tubes similar to those of pterobranchs.[52]

Echinoderms

Echinoderms differ from chordates and their other relatives in three conspicuous ways: they possess bilateral symmetry only as larvae - in adulthood they have radial symmetry, meaning that their body pattern is shaped like a wheel; they have tube feet; and their bodies are supported by skeletons made of calcite, a material not used by chordates. Their hard, calcified shells keep their bodies well protected from the environment, and these skeletons enclose their bodies, but are also covered by thin skins. The feet are powered by another unique feature of echinoderms, a water vascular system of canals that also functions as a "lung" and surrounded by muscles that act as pumps. Crinoids look rather like flowers, and use their feather-like arms to filter food particles out of the water; most live anchored to rocks, but a few can move very slowly. Other echinoderms are mobile and take a variety of body shapes, for example starfish, sea urchins and sea cucumbers.[53]

History of name

Although the name Chordata is attributed to William Bateson (1885), it was already in prevalent use by 1880. Ernst Haeckel described a taxon comprising tunicates, cephalochordates, and vertebrates in 1866. Though he used the German vernacular form, it is allowed under the ICZN code because of its subsequent latinization.[2]

See also

- Chordate genomics

- List of chordate orders – All the classes and orders of phylum Chordata

References

- Haeckel, E. (1874). Anthropogenie oder Entwicklungsgeschichte des Menschen. Leipzig: Engelmann.

- Nielsen, C. (July 2012). "The authorship of higher chordate taxa". Zoologica Scripta. 41 (4): 435–436. doi:10.1111/j.1463-6409.2012.00536.x.

- García-Bellido, Diego C; Paterson, John R (2014). "A new vetulicolian from Australia and its bearing on the chordate affinities of an enigmatic Cambrian group". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 14: 214. doi:10.1186/s12862-014-0214-z. PMC 4203957. PMID 25273382.

- Rychel, A.L.; Smith, S.E.; Shimamoto, H.T. & Swalla, B.J. (March 2006). "Evolution and Development of the Chordates: Collagen and Pharyngeal Cartilage". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 23 (3): 541–549. doi:10.1093/molbev/msj055. PMID 16280542.

- Ruppert, E. (January 2005). "Key characters uniting hemichordates and chordates: homologies or homoplasies?". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 83: 8–23. doi:10.1139/Z04-158. Archived from the original on 9 December 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2008.

- Valentine, J.W. (2004). On the Origin of Phyla. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-226-84548-7.

- R.C.Brusca, G.J.Brusca. Invertebrates. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland Mass 2003 (2nd ed.), p. 47, ISBN 0-87893-097-3.

- Benton, M.J. (2004). Vertebrate Palaeontology, Third Edition. Blackwell Publishing. The classification scheme is available online Archived 19 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Benton, Michael J. (2014). Vertebrate Palaeontology (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-40764-6.

- Nelson, J. S. (2006). Fishes of the World (4th ed.). New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. ISBN 978-0-471-25031-9.

- Benton, M.J. (2004). Vertebrate Paleontology. 3rd ed. Blackwell Science Ltd.

- Frost, Darrel R. "ASW Home". Amphibian Species of the World, an Online Reference. Version 6.0. American Museum of Natural History, New York. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- "Reptiles face risk of extinction". 15 February 2013 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- "New Study Doubles the Estimate of Bird Species in the World". Amnh.org. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- Benton, M.J. (14 April 2000). Vertebrate Palaeontology: Biology and Evolution. Blackwell Publishing. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-632-05614-9. Retrieved 22 September 2008.

- Gee, H. (19 June 2008). "Evolutionary biology: The amphioxus unleashed". Nature. 453 (7198): 999–1000. Bibcode:2008Natur.453..999G. doi:10.1038/453999a. PMID 18563145.

- "Branchiostoma". Lander University. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

- Benton, M.J. (14 April 2000). Vertebrate Palaeontology: Biology and Evolution. Blackwell Publishing. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-632-05614-9.

- "Animal fact files: salp". BBC. Retrieved 22 September 2008.

- "Appendicularia" (PDF). Australian Government Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2011. Retrieved 28 October 2008.

- Oxford English Dictionary, Third Edition, January 2009: Urochordata

- Benton, M.J. (14 April 2000). Vertebrate Palaeontology: Biology and Evolution. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-0-632-05614-9. Retrieved 22 September 2008.

- "Morphology of the Vertebrates". University of California Museum of Paleontology. Retrieved 23 September 2008.

- "Introduction to the Myxini". University of California Museum of Paleontology. Archived from the original on 15 December 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2008.

- Campbell, N.A. and Reece, J.B. (2005). Biology (7th ed.). San Francisco, CA: Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 978-0-8053-7171-0.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Janvier, P. (2010). "MicroRNAs revive old views about jawless vertebrate divergence and evolution". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (45): 19137–19138. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10719137J. doi:10.1073/pnas.1014583107. PMC 2984170. PMID 21041649.

Although I was among the early supporters of vertebrate paraphyly, I am impressed by the evidence provided by Heimberg et al. and prepared to admit that cyclostomes are, in fact, monophyletic. The consequence is that they may tell us little, if anything, about the dawn of vertebrate evolution, except that the intuitions of 19th century zoologists were correct in assuming that these odd vertebrates (notably, hagfishes) are strongly degenerate and have lost many characters over time

- "Introduction to the Petromyzontiformes". University of California Museum of Paleontology. Archived from the original on 24 January 2018. Retrieved 28 October 2008.

- Shigehiro Kuraku, S.; Hoshiyama, D.; Katoh, K.; Suga, H & Miyata, T. (December 1999). "Monophyly of Lampreys and Hagfishes Supported by Nuclear DNA-Coded Genes". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 49 (6): 729–735. Bibcode:1999JMolE..49..729K. doi:10.1007/PL00006595. PMID 10594174.

- Delabre, Christiane; et al. (2002). "Complete Mitochondrial DNA of the Hagfish, Eptatretus burgeri: The Comparative Analysis of Mitochondrial DNA Sequences Strongly Supports the Cyclostome Monophyly". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 22 (2): 184–192. doi:10.1006/mpev.2001.1045. PMID 11820840.

- Shu, D-G.; Conway Morris, S. & Han, J. (January 2003). "Head and backbone of the Early Cambrian vertebrate Haikouichthys". Nature. 421 (6922): 526–529. Bibcode:2003Natur.421..526S. doi:10.1038/nature01264. PMID 12556891.

- Josh Gabbatiss (15 August 2016), Why we have a spine when over 90% of animals don't, BBC

- Holland, N. D. (22 November 2005). "Chordates". Curr. Biol. 15 (22): R911–4. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.11.008. PMID 16303545.

- Erwin, Douglas H.; Eric H. Davidson (1 July 2002). "The last common bilaterian ancestor". Development. 129 (13): 3021–3032. PMID 12070079.

- New data on Kimberella, the Vendian mollusc-like organism (White sea region, Russia): palaeoecological and evolutionary implications (2007), "Fedonkin, M.A.; Simonetta, A; Ivantsov, A.Y.", in Vickers-Rich, Patricia; Komarower, Patricia (eds.), The Rise and Fall of the Ediacaran Biota, Special publications, 286, London: Geological Society, pp. 157–179, doi:10.1144/SP286.12, ISBN 9781862392335, OCLC 156823511CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Butterfield, N.J. (December 2006). "Hooking some stem-group "worms": fossil lophotrochozoans in the Burgess Shale". BioEssays. 28 (12): 1161–6. doi:10.1002/bies.20507. PMID 17120226.

- Dzik, J. (June 1999). "Organic membranous skeleton of the Precambrian metazoans from Namibia". Geology. 27 (6): 519–522. Bibcode:1999Geo....27..519D. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1999)027<0519:OMSOTP>2.3.CO;2.Ernettia is from the Kuibis formation, approximate date given by Waggoner, B. (2003). "The Ediacaran Biotas in Space and Time". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 43 (1): 104–113. doi:10.1093/icb/43.1.104. PMID 21680415.

- Bengtson, S. (2004). Lipps, J.H.; Waggoner, B.M. (eds.). "Early skeletal fossils" (PDF). The Paleontological Society Papers: Neoproterozoic - Cambrian Biological Revolutions. 10: 67–78. doi:10.1017/S1089332600002345. Retrieved 18 July 2008.

- Bengtson, S.; Urbanek, A. (October 2007). "Rhabdotubus, a Middle Cambrian rhabdopleurid hemichordate". Lethaia. 19 (4): 293–308. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1986.tb00743.x. Archived from the original on 16 December 2012.

- Shu, D., Zhang, X. and Chen, L. (April 1996). "Reinterpretation of Yunnanozoon as the earliest known hemichordate". Nature. 380 (6573): 428–430. Bibcode:1996Natur.380..428S. doi:10.1038/380428a0.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Chen, J-Y.; Hang, D-Y.; Li, C.W. (December 1999). "An early Cambrian craniate-like chordate". Nature. 402 (6761): 518–522. Bibcode:1999Natur.402..518C. doi:10.1038/990080.

- Shu, D-G.; Conway Morris, S.; Zhang, X-L. (November 1999). "Lower Cambrian vertebrates from south China" (PDF). Nature. 402 (6757): 42. Bibcode:1999Natur.402...42S. doi:10.1038/46965. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2009. Retrieved 23 September 2008.

- Shu, D-G.; Conway Morris, S.; Zhang, X-L. (November 1996). "A Pikaia-like chordate from the Lower Cambrian of China". Nature. 384 (6605): 157–158. Bibcode:1996Natur.384..157S. doi:10.1038/384157a0.

- Conway Morris, S. (2008). "A Redescription of a Rare Chordate, Metaspriggina walcotti Simonetta and Insom, from the Burgess Shale (Middle Cambrian), British Columbia, Canada". Journal of Paleontology. 82 (2): 424–430. doi:10.1666/06-130.1. Retrieved 28 April 2009.

- Winchell, C. J.; Sullivan, J.; Cameron, C. B.; Swalla, B. J. & Mallatt, J. (1 May 2002). "Evaluating Hypotheses of Deuterostome Phylogeny and Chordate Evolution with New LSU and SSU Ribosomal DNA Data". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 19 (5): 762–776. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004134. PMID 11961109.

- Blair, J. E.; Hedges, S. B. (November 2005). "Molecular Phylogeny and Divergence Times of Deuterostome Animals". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 22 (11): 2275–2284. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi225. PMID 16049193.

- Ayala, F. J. (January 1999). "Molecular clock mirages". BioEssays. 21 (1): 71–75. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199901)21:1<71::AID-BIES9>3.0.CO;2-B. PMID 10070256.

- Schwartz, J. H.; Maresca, B. (December 2006). "Do Molecular Clocks Run at All? A Critique of Molecular Systematics". Biological Theory. 1 (4): 357–371. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.534.4060. doi:10.1162/biot.2006.1.4.357.

- Putnam, N. H.; Butts, T.; Ferrier, D. E. K.; Furlong, R. F.; Hellsten, U.; Kawashima, T.; Robinson-Rechavi, M.; Shoguchi, E.; Terry, A.; Yu, J. K.; Benito-Gutiérrez, E. L.; Dubchak, I.; Garcia-Fernàndez, J.; Gibson-Brown, J. J.; Grigoriev, I. V.; Horton, A. C.; De Jong, P. J.; Jurka, J.; Kapitonov, V. V.; Kohara, Y.; Kuroki, Y.; Lindquist, E.; Lucas, S.; Osoegawa, K.; Pennacchio, L. A.; Salamov, A. A.; Satou, Y.; Sauka-Spengler, T.; Schmutz, J.; Shin-i, T. (June 2008). "The amphioxus genome and the evolution of the chordate karyotype". Nature. 453 (7198): 1064–1071. Bibcode:2008Natur.453.1064P. doi:10.1038/nature06967. PMID 18563158.

- Ota, K. G.; Kuratani, S. (September 2007). "Cyclostome embryology and early evolutionary history of vertebrates". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 47 (3): 329–337. doi:10.1093/icb/icm022. PMID 21672842.

- Delsuc F, Philippe H, Tsagkogeorga G, Simion P, Tilak MK, Turon X, López-Legentil S, Piette J, Lemaire P, Douzery EJ (April 2018). "A phylogenomic framework and timescale for comparative studies of tunicates". BMC Biology. 16 (1): 39. doi:10.1186/s12915-018-0499-2. PMC 5899321. PMID 29653534.

- Goujet, Daniel F (16 February 2015), "Placodermi (Armoured Fishes)", ELS, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 1–7, doi:10.1002/9780470015902.a0001533.pub2, ISBN 9780470015902

- "Introduction to the Hemichordata". University of California Museum of Paleontology. Archived from the original on 1 February 2019. Retrieved 22 September 2008.

- Cowen, R. (2000). History of Life (3rd ed.). Blackwell Science. p. 412. ISBN 978-0-632-04444-3.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Chordata |

| The Wikibook Dichotomous Key has a page on the topic of: Chordata |