Xenacoelomorpha

Xenacoelomorpha[2] is a basal bilaterian phylum of small and very simple animals, grouping the xenoturbellids with the acoelomorphs. This grouping was suggested by morphological synapomorphies,[3] and confirmed by phylogenomic analyses of molecular data.[2][4] Xenacoelomorphs emerged with the Nephrozoa as their sister clade.

| Xenacoelomorpha | |

|---|---|

| |

| Xenoturbella japonica, a xenacoelomorph member (xenoturbellids) | |

| |

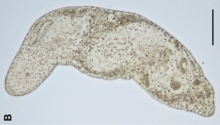

| Proporus sp., another xenacoelomorph member (acoelomorphs) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Subkingdom: | Eumetazoa |

| Clade: | ParaHoxozoa |

| Clade: | Bilateria |

| Phylum: | Xenacoelomorpha Philippe et al. 2011[1] |

| Subphyla | |

Phylogenetics

The clade Xenacoelomorpha, grouping Acoelomorpha and the genus Xenoturbella, was revealed by molecular studies.[4] Initially it was considered to be a member of the deuterostomes,[2] but a more recent transcriptome analysis concluded that it is the sister group to the Nephrozoa, which includes the protostomes and the deuterostomes, being therefore the basalmost bilaterian clade.[5][6]

Characteristics

All xenacoelomorphs lack a typical stomatogastric system, i.e., they do not have a true gut. In acoels, the mouth opens directly into a large endodermal syncytium, while in nemertodermatids and xenoturbellids there is a sack-like gut lined by unciliated cells.[7]

The nervous system is basiepidermal, i.e., located right under the epidermis, and a brain is absent. In xenoturbellids it is constituted by a simple nerve net without any special concentration of neurons, while in acoelomorphs it is arranged in a series of longitudinal bundles united in the anterior region by a ring comissure of variable complexity.[8]

The sensory organs include a statocyst and, in some groups, two unicellular ocelli.[7][8]

The epidermis of all xenacoelomorphans is ciliated. The cilia are composed of a set of 9 pairs of peripheral microtubules and one or two central microtubules (patterns 9+1 and 9+2, respectively). The pairs 4–7 terminate before the tip, creating a structure called a "shelf".[9]

References

- Tyler, S.; Schilling, S.; Hooge, M.; Bush, L.F. (2006–2016). "Xenacoelomorpha". Turbellarian taxonomic database. Version 1.7. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- Philippe, H.; Brinkmann, H.; Copley, R. R.; Moroz, L. L.; Nakano, H.; Poustka, A. J.; Wallberg, A.; Peterson, K. J.; Telford, M. J. (10 February 2011). "Acoelomorph flatworms are deuterostomes related to Xenoturbella". Nature. 470 (7333): 255–258. Bibcode:2011Natur.470..255P. doi:10.1038/nature09676. PMC 4025995. PMID 21307940.

- Lundin, K (1998). "The epidermal ciliary rootlets of Xenoturbella bocki (Xenoturbellida) revisited: new support for a possible kinship with the Acoelomorpha (Platyhelminthes)". Zoologica Scripta. 27 (3): 263–270. doi:10.1111/j.1463-6409.1998.tb00440.x.

- Hejnol, A.; Obst, M.; Stamatakis, A.; Ott, M.; Rouse, G. W.; Edgecombe, G. D.; et al. (2009). "Assessing the root of bilaterian animals with scalable phylogenomic methods". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 276 (1677): 4261–4270. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0896. PMC 2817096. PMID 19759036.

- Perseke, M.; Hankeln, T.; Weich, B.; Fritzsch, G.; Stadler, P.F.; Israelsson, O.; Bernhard, D.; Schlegel, M. (August 2007). "The mitochondrial DNA of Xenoturbella bocki: genomic architecture and phylogenetic analysis" (PDF). Theory Biosci. 126 (1): 35–42. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.177.8060. doi:10.1007/s12064-007-0007-7. PMID 18087755.

- Cannon, J.T.; Vellutini, B.C.; Smith, J.; Ronquist, F.; Jondelius, U.; Hejnol, A. (4 February 2016). "Xenacoelomorpha is the sister group to Nephrozoa". Nature. 530 (7588): 89–93. Bibcode:2016Natur.530...89C. doi:10.1038/nature16520. PMID 26842059.

- Achatz, Johannes G.; Chiodin, Marta; Salvenmoser, Willi; Tyler, Seth; Martinez, Pedro (June 2013). "The Acoela: on their kind and kinships, especially with nemertodermatids and xenoturbellids (Bilateria incertae sedis)". Organisms Diversity & Evolution. 13 (2): 267–286. doi:10.1007/s13127-012-0112-4. ISSN 1439-6092. PMC 3789126. PMID 24098090.

- Perea-Atienza, E.; Gavilan, B.; Chiodin, M.; Abril, J. F.; Hoff, K. J.; Poustka, A. J.; Martinez, P. (2015). "The nervous system of Xenacoelomorpha: a genomic perspective". Journal of Experimental Biology. 218 (4): 618–628. doi:10.1242/jeb.110379. ISSN 0022-0949. PMID 25696825.

- Franzen, Ake; Afzelius, Bjorn A. (January 1987). "The ciliated epidermis of Xenoturbella bocki (Platyhelminthes, Xenoturbellida) with some phylogenetic considerations". Zoologica Scripta. 16 (1): 9–17. doi:10.1111/j.1463-6409.1987.tb00046.x. ISSN 0300-3256.

See also

- List of bilaterial animal orders