Chinatown, Manhattan

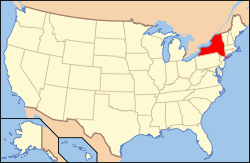

Manhattan's Chinatown (simplified Chinese: 曼哈顿华埠; traditional Chinese: 曼哈頓華埠; pinyin: Mànhādùn huábù; Jyutping: Maan6haa1deon6 waa1bou6) is a neighborhood in Lower Manhattan, New York City, bordering the Lower East Side to its east, Little Italy to its north, Civic Center to its south, and Tribeca to its west. With an estimated population of 90,000 to 100,000 people, Chinatown is home to the highest concentration of Chinese people in the Western Hemisphere.[5] Manhattan's Chinatown is also one of the oldest Chinese ethnic enclaves.[6] The Manhattan Chinatown is one of nine Chinatown neighborhoods in New York City, as well as one of twelve in the New York metropolitan area, which contains the largest ethnic Chinese population outside of Asia, comprising an estimated 893,697 uniracial individuals as of 2017.[7]

Chinatown | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Crossing Canal Street in Chinatown, facing Mott Street toward the south | |||||||||||||||||||

Location in New York City | |||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates: 40.715°N 73.997°W | |||||||||||||||||||

| Country | |||||||||||||||||||

| State | |||||||||||||||||||

| City | New York City | ||||||||||||||||||

| Borough | Manhattan | ||||||||||||||||||

| Community District | Manhattan 3[1] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||

| • Total | 1.99 km2 (0.768 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Population (2010)[2] | |||||||||||||||||||

| • Total | 47,844 | ||||||||||||||||||

| • Density | 24,000/km2 (62,000/sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Ethnicity | |||||||||||||||||||

| • Asian | 63.9% | ||||||||||||||||||

| • White | 16.3% | ||||||||||||||||||

| • Hispanic | 13.4% | ||||||||||||||||||

| • Black | 4.8% | ||||||||||||||||||

| • Other | 1.6% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Economics | |||||||||||||||||||

| • Median income | $68,657 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) | ||||||||||||||||||

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) | ||||||||||||||||||

| ZIP Codes | 10002, 10013 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Area code | 212, 332, 646, and 917 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 曼哈頓華埠 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 曼哈顿华埠 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

Historically, Chinatown was primarily populated by Cantonese speakers. However, in the 1980s and 1990s, large numbers of Fuzhounese-speaking immigrants also arrived and formed a sub-neighborhood annexed to the eastern portion of Chinatown east of The Bowery, which has become known as Little Fuzhou (小福州) subdivided away from the primarily Cantonese populated original long time established Chinatown of Manhattan from the proximity of The Bowery going west, known as Little Hong Kong/Guangdong (小粵港). As many Fuzhounese and Cantonese speakers now speak Mandarin—the official language in Mainland China and Taiwan—in addition to their native languages, this has made it more important for Chinatown residents to learn and speak Mandarin.[8] Although now overtaken in size by the rapidly growing Flushing Chinatown (法拉盛華埠), located in the New York City borough of Queens,[9] the Manhattan Chinatown remains a dominant cultural force for the Chinese diaspora, as home to the Museum of Chinese in America and as the headquarters of numerous publications based both in the U.S. and China that are geared to overseas Chinese.

Chinatown is part of Manhattan Community District 3 and it is primary ZIP Codes are 10013 and 10002.[1] It is patrolled by the 5th Precinct of the New York City Police Department.

Location

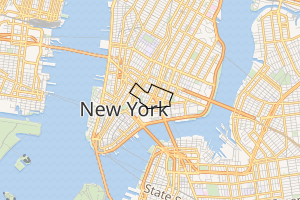

Although a Business Improvement District has been identified for support,[10] Chinatown has no officially defined borders, but they have been commonly considered to be approximated by the following streets:[11]

- Hester Street or Grand Street to the north,[11][12] bordering or overlapping Little Italy

- Worth Street to the southwest, bordering Civic Center

- East Broadway to the southeast, bordering Two Bridges

- Essex Street to the east, bordering the Lower East Side

- Lafayette Street to the west, bordering Tribeca

Citywide demographics

The Manhattan Chinatown is one of nine Chinatown neighborhoods in New York City, as well as one of twelve in the New York metropolitan area, which contains the largest ethnic Chinese population outside of Asia, enumerating an estimated 779,269 individuals as of 2013;[13] the remaining Chinatowns are located in the boroughs of Queens (up to four, depending upon definition)[14] and Brooklyn (three) and in Nassau County, all on Long Island in New York State; as well as in Edison[15] and Parsippany-Troy Hills in New Jersey. In addition, Manhattan's Little Fuzhou (小福州, 紐約華埠), an enclave populated primarily by more recent Chinese immigrants from the Fujian Province of China, is technically considered a part of Manhattan's Chinatown, albeit now developing a separate identity of its own.

A new and rapidly growing Chinese community is now forming in East Harlem (東哈萊姆), Uptown Manhattan, nearly tripling in population between the years 2000 and 2010, according to U.S. Census figures.[16][17][18][19] This neighborhood has been described as the precursor to a new satellite Chinatown within Manhattan itself,[20] which upon acknowledged formation would represent the second Chinese neighborhood in Manhattan, the tenth large Chinese settlement in New York City, and the twelfth within the overall New York City metropolitan region.

As the city proper with the largest ethnic Chinese population outside of Asia by a wide margin, estimated at 628,763 as of 2017,[21] and as the primary destination for new Chinese immigrants,[22] New York City is subdivided into official municipal boroughs, which themselves are home to significant Chinese populations, with Brooklyn and Queens, adjacently located on Long Island, leading the fastest growth.[23][24] After the City of New York itself, the boroughs of Queens and Brooklyn encompass the largest Chinese populations, respectively, of all municipalities in the United States.

| Rank | Borough | Chinese Americans | Density of Chinese Americans per square mile in borough | Percentage of Chinese Americans in borough's population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Queens, Chinatowns (皇后華埠) (2014)[25] | 237,484 | 2,178.8 | 10.2 |

| 2 | Brooklyn, Chinatowns (布魯克林華埠) (2014)[26] | 205,753 | 2,897.9 | 7.9 |

| 3 | Manhattan, Chinatown (曼哈頓華埠) (2014)[27] | 107,609 | 4,713.5 | 6.6 |

| 4 | Staten Island (2012) | 13,620 | 232.9 | 2.9 |

| 5 | The Bronx (2012) | 6,891 | 164 | 0.5 |

| New York City (2014) | 573,388[28] | 1,881.1 | 6.8 |

History

Ah Ken and early Chinese immigration

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1990 | 51,439 | — | |

| 2000 | 59,320 | 15.3% | |

| 2010 | 52,613 | −11.3% | |

| Asian American population [29] | |||

Ah Ken is claimed to have arrived in the area during the 1850s; he is the first Chinese person credited as having permanently immigrated to Chinatown. As a Cantonese businessman, Ah Ken eventually founded a successful cigar store on Park Row.[30][31][32][33] He first arrived around 1858 in New York City, where he was "probably one of those Chinese mentioned in gossip of the sixties [1860s] as peddling 'awful' cigars at three cents apiece from little stands along the City Hall park fence – offering a paper spill and a tiny oil lamp as a lighter", according to author Alvin Harlow in Old Bowery Days: The Chronicles of a Famous Street (1931).[31]

In the 1850s, the California Gold Rush brought a wave of Chinese immigration to the United States. Approximately 25,000 Chinese immigrants left their homes in search for gam saan ("gold mountain") in California.[34] In New York, immigrants found work as "cigar men" or carrying billboards, and Ah Ken's particular success encouraged cigar makers William Longford, John Occoo, and John Ava to also ply their trade in Chinatown, eventually forming a monopoly on the cigar trade.[35] It has been speculated that it may have been Ah Ken who kept a small boarding house on lower Mott Street and rented out bunks to the first Chinese immigrants to arrive in Chinatown. It was with the profits he earned as a landlord, earning an average of $100 per month, that he was able to open his Park Row smoke shop around which modern-day Chinatown would grow.[30][32][36][37]

Chinese exclusion period

In 1873, the United States entered a period of economic difficulty, known as the Long Depression.[38] As a result, immigrants increasingly competed for professions that were typically performed by Chinese immigrants. The period was marked by increased racial discrimination, anti-Chinese riots (particularly in California),[39] and new laws that prevented participation in many occupations on the U.S. West Coast. Consequently, some Chinese immigrants moved to the East Coast cities in search of employment.

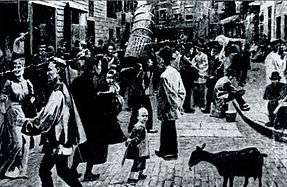

Early businesses in East Coast cities included hand laundries and restaurants. Chinatown started on Mott, Park (now Mosco), Pell, and Doyers Streets, east of the notorious Five Points district. By 1870, there was a Chinese population of 200. By the time the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was passed, the population was up to 2,000 residents. In 1900, the US Census reported 7,028 Chinese males in residence, but only 142 Chinese women. This significant gender inequality remained present until the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943.[40] Wenfei Wang, Shangyi Zhou, and C. Cindy Fan, authors of "Growth and Decline of Muslim Hui Enclaves in Beijing", wrote that because of immigration restrictions, Chinatown continued to be "virtually a bachelor society" until 1965.[41]

The early days of Chinatown were dominated by Chinese "tongs" (now sometimes rendered neutrally as "associations"), which were a mixture of clan associations, landsman's associations, political alliances (Kuomintang (Nationalists) vs Communist Party of China), and more secretly, crime syndicates. The associations started to give protection from harassment due to anti-Chinese sentiment. Each of these associations was aligned with a street gang. The associations were a source of assistance to new immigrants, giving out loans, aiding in starting businesses, and so forth. The associations formed a governing body named the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (中華公所). Though this body was meant to foster relations between the Tongs, open warfare periodically flared between the On Leong (安良) and Hip Sing (協勝) tongs. Much of the Chinese gang warfare took place on Doyers street. Gangs like the Ghost Shadows (鬼影) and Flying Dragons (飛龍) were prevalent until the 1990s. The Chinese gangs controlled certain territories of Manhattan's Chinatown. The On Leong (安良) and its affiliate Ghost Shadows (鬼影) were of Cantonese and Toishan descent, and controlled Mott, Bayard, Canal, and Mulberry Streets. The Flying Dragons (飛龍) and its affiliate Hip Sing (協勝) also of Cantonese and Toishan descent controlled Doyers, Pell, Bowery, Grand, and Hester Streets. Other Chinese gangs also existed, like the Hung Ching and Chih Kung gangs of Cantonese and Toishan descent, which were affiliated with each other and also gained control of Mott Street. Born to Kill, also known as the Canal Boys, a gang composed almost entirely of Vietnamese immigrants from the Vietnam War under the leadership of David Thai had control over Broadway, Canal, Baxter, Centre, and Lafayette Streets.[42] Fujianese gangs also existed, such as the Tung On gang, which affiliated with Tsung Tsin, and had control over East Broadway, Catherine and Division Streets and the Fuk Ching gang affiliated with Fukien American controlled East Broadway, Chrystie, Forsyth, Eldridge, and Allen Streets. At one point, a gang named the Freemasons gang, which was of Cantonese descent, had attempted to claim East Broadway as its territory.[43][44]:75[45][46]

Columbus Park, the only park in Chinatown, was built on what was once the center of the infamous Five Points neighborhood. During the 19th century, this was the most dangerous ghetto area of immigrant New York, as portrayed in the book and film Gangs of New York.[47]

Post-1965 reform

In the years after the United States enacted the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, allowing many more immigrants from Asia into the country, the population of Chinatown increased dramatically. Geographically, much of the growth occurred in neighborhoods to the north. The Chinatown grew and became more oriented toward families due to the lifting of restrictions.[41] In the earliest years of the existence of Manhattan's Chinatown, it had been primarily populated by Taishanese-speaking Chinese immigrants and the borderlines of the enclave was originally Canal Street to the north, Bowery to the east, Worth Street to the south, and Mulberry Street to the west.

Influx of immigrants from Hong Kong and Guangdong

After 1965, there came a wave of Cantonese speakers from Hong Kong and Guangdong province in Mainland China, and Standard Cantonese became the dominant tongue. With the influx of Hong Kong immigrants, it was developing and growing into a Hong Kongese neighborhood, however the growth slowed down later on during the 1980s-90s.[48][49]

Through the 1970s and 1980s, the influx of Guangdong and Hong Kong immigrants began to develop newer portions of Manhattan's Chinatown going north of Canal Street and then later the east of the Bowery. However, until the 1980s, the western section was the most primarily fully Chinese developed and populated part of Chinatown and the most quickly flourishing busy central Chinese business district with still a little bit of remaining Italians in the very northwest portion around Grand Street and Broome Street, which eventually all moved away and became all Chinese by the 1990s.[50][51][52] Although the portion of Chinatown that is east of the Bowery—which is considered part of the Lower East Side already started developing as being part of Chinatown since the influx of Chinese immigrants started spilling over into that section since the 1960s, however until the 1980s, it was still not developing as quickly as the western portion of Chinatown because the proportion and concentration of Chinese residents in the eastern section during that time was comparatively growing at a slower rate and being more scattered than the western section in addition to the fact that there was a higher proportion of remaining non-Chinese residents consisting of Jewish, Puerto Ricans, and a few Italians and African Americans than Chinatown's western section.[53]

During the 1970s and 1980s, the eastern portion of Chinatown east of the Bowery was a very quiet section, and like in all of the rest of the Lower East Side, many people and especially many Chinese people were afraid to walk through or even reside on the streets east of the Bowery due to deteriorating building conditions and high crime rates such as gang activities, robberies, building burglaries, and rape as well as fear of racial tensions with other ethnic people that were still residing there, however there were already a lot of Chinese immigrants moving into that section because of the availability of vacant affordable apartments, which were more difficult to find in the western portion of Chinatown. In addition, there were fewer businesses and there were significant amount of vacant properties not occupied.[54] Chinese female garment workers were especially targets of robbery and rape a lot on their way home from work and often left work together as a group to protect each other as they were heading home.[55][56][57][58][59] In May 1985, a gang-related shooting injured seven people, including a 4-year-old boy, at 30 East Broadway in Chinatown. Two males, who were 15 and 16 years old and were members of a Chinese street gang, were arrested and convicted.[60][61][62][63]

Starting in the 1970s and especially throughout the 1980s-90s, Mandarin-speaking Taiwanese immigrants and then later on many other Non-Cantonese Chinese immigrants also were arriving into New York City. However, due to the traditional dominance of Cantonese-speaking residents, which were largely working class in Manhattan's Chinatown and the neighborhood's poor housing conditions, they were unable to relate to Manhattan's Chinatown and mainly settled in Flushing and created a more middle class Mandarin-Speaking Chinatown or Mandarin Town (國語埠) and even smaller one in Elmhurst, since most of the newer upcoming generations of ethnic Chinese were already using Mandarin although still their regional dialects in everyday conversations, whereas Cantonese speaking populations largely don't speak Mandarin or only speak it with other Non-Cantonese Chinese speakers. As a result, Manhattan's Chinatown and Brooklyn's emerging Chinatown were able to continue retaining its traditional almost exclusive Cantonese society and were nearly successful at permanently keeping its Cantonese dominance. However, there was already a small and slow-growing Fuzhou immigrant population in Manhattan's Chinatown since the 1970s-80s in the eastern section of Chinatown east of the Bowery, which was still underdeveloped as being part of Chinatown. In the 1990s, though, Chinese people began to move into some parts of the western Lower East Side, which 50 years earlier was populated by Eastern European Jews and 20 years earlier was occupied by Hispanics.

Little Fuzhou

From the late 1980s through the 1990s, when a large influx of Fuzhou immigrants, who also largely speak Mandarin along with their Fuzhou dialect started to arrive into New York City, they were the only exceptional Non-Cantonese Chinese group to largely settle in Manhattan's Chinatown and eventually Brooklyn's Chinatown, which was also originally Cantonese dominated. This is due to many of them having no legal status and being forced into the lowest paying jobs, Manhattan's Chinatown was the only place they can receive affordable housing and be around other Chinese people despite the heavy Cantonese dominance until the 1990s since the more Mandarin-speaking enclaves in Flushing and Elmhurst would be too expensive to rent a vacancy.

Since the Fuzhou immigrants have a strong cultural and linguistic background different from the Cantonese people, the Fuzhou immigrants were unable to integrate well into Manhattan's Chinatown, which was still very Cantonese dominated and as a result, they settled in the eastern portion of Chinatown, which was still an overlap of Chinese, Hispanics, and Jewish in addition the higher availability of housing vacancies is another reason why they settled in that section. The eastern section became more fully developed as being part of Chinatown, and these new immigrants began to establish their own Fuzhou community along East Broadway and Eldridge Street. This has resulted in referring to East Broadway as Fuzhou Street No. 1, which emerged during the late 1980s-early 1990s and Eldridge Street as Fuzhou Street No. 2, which developed more towards after the mid-1990s-early 2000s.

Little Fuzhou started becoming known as the new Chinatown of Manhattan, separate from the long time heavily dominated Cantonese community, which is the western section of Chinatown or the Old Chinatown of Manhattan; although significant minor to moderate numbers of long time Cantonese people and businesses still continue to exist in the eastern portion of Chinatown.[64][65]:20

Not only did the Fuzhou immigration influx establish a new portion of Manhattan's Chinatown, they contributed significantly in maintaining the Chinese population in the neighborhood, they also played a role in property values increasing quickly during the 1990s, in contrast to during the 1980s, when the housing prices were dropping. As a result, landlords were able to generate twice as much income in Manhattan's Chinatown, Flushing's Chinatown and eventually Brooklyn's Chinatown.[66]:114

Very soon, in the early 2000s, gentrification immediately came into Manhattan's Chinatown and in addition to the shortage of housing vacancies, it caused the Fuzhou influx to shift to Brooklyn's Chinatown, which was now the most affordable New York City Chinese enclave to live in and unlike in Manhattan's Chinatown where the Fuzhou population continues to be mainly concentrated, although now has been slowly declining since the 2000s due to gentrification in the East Broadway and Eldridge Street portion, the Fuzhou immigrant population has now managed to dominate the whole Brooklyn's Chinatown diluting the Cantonese population as well as sidelining Manhattan's Chinatown's Little Fuzhou as the Fuzhou cultural center in New York City. Brooklyn's Chinatown then became more fully developed and as well as causing its ethnic enclave size to expand tremendously as a result of the shift of the Fuzhou influx.[67]

Migration to Brooklyn Chinatown

During the late 1980s and 1990s, most of the new Fuzhou immigrants arriving into New York City were settling in Manhattan's Chinatown and later formed the first Fuzhou community in the city amongst the waves of Cantonese who had settled in Chinatown over decades. However, by the 2000s, the increasing Fuzhou influx had shifted into the Brooklyn Chinatown in the Sunset Park section of the Brooklyn borough of New York City. This shift replaces the Cantonese population throughout Brooklyn's Sunset Park Chinatown significantly more rapidly than in Manhattan's Chinatown.[68] Gentrification in Manhattan's Chinatown has slowed the growth of Fuzhou immigration as well as the growth of Chinese immigrants to Manhattan in general,[69] which is why New York City's rapidly growing Chinese population has now shifted primarily to the boroughs of Queens and Brooklyn.

Some Chinese landlords in Manhattan, especially the many real estate agencies that are mainly of Cantonese ownership, were accused of prejudice against the Fuzhou immigrants, supposedly making Fuzhou immigrants feel unwelcome because concerns that they would not be able to pay rent or debt to gangs that may have helped smuggled them in illegally into the United States, and because of fear that gangs will come up to the apartments to cause trouble.[66]:108[70] There is also supposedly a concern that Fujianese are more likely to make the apartments too overcrowded by subdividing an apartment into multiple small spaces to rent to other Fuzhou immigrants. East Broadway, Manhattan's center of Fuzhou culture, has perhaps the most blatant results of illegal apartment subdivisions including having many bunk beds in just one small room.[71] Because they fear being evicted by Cantonese landlords, many Fuzhou immigrants resort to renting a tiny space from Fujianese landlords inside apartments already occupied by Fuzhou immigrants.

Although Mandarin is spoken as a native language among only ten percent of Chinese speakers in Manhattan's Chinatown, it is used as a secondary dialect among the greatest number of them. Although Min Chinese, especially the Fuzhou dialect, is spoken natively by a third of the Chinese population in the city, it is not used as a lingua franca because speakers of other dialect groups do not learn Min.[72]

Little Hong Kong/Guangdong

As the epicenter of the massive Fuzhou influx has shifted to Brooklyn in the 2000s, Manhattan's Chinatown's Cantonese population remains viable and large and successfully continues to retain its stable Cantonese community identity, maintaining the communal gathering venue established decades ago in the western portion of Chinatown, to shop, work, and socialize—in contrast to the Cantonese population and community identity which are shifting from Brooklyn's original Sunset Park Chinatown to the satellite Chinatowns in Brooklyn.

Although the term Little Hong Kong (小香港) was used a long time ago to describe Manhattan's Chinatown relating to when an influx of Hong Kong immigrants was pouring in at that time and even though not all Cantonese immigrants come from Hong Kong, this portion of Chinatown has heavy Cantonese characteristics, especially with the Standard Cantonese, which is spoken in Hong Kong and Guangzhou, China being widely used, so it is in many ways a Little Hong Kong.

A more appropriate term would be Little Guangdong-Hong Kong (小粵港) or Cantonese-Hong Kong Town (粵港埠) since the Cantonese immigrants do come from different regions of the Guangdong province of China including Hong Kong. The long-time established Cantonese Community, which can be considered Little Hong Kong/Guang Dong or known as the Old Chinatown of Manhattan lies along Mott, Pell, Doyer, Bayard, Elizabeth, Mulberry, Canal, and Bowery Streets, within Manhattan's Chinatown.[50][51]

Newer satellite Little Guangdong-Hong Kong has started to emerge in sections of Bensonhurst and Sheepshead Bay/Homecrest in Brooklyn. However, there are more scattered and mixed in with other ethnic enclaves. This is a result of many Cantonese residents migrating to these neighborhoods. Bensonhurst carries the majority of Brooklyn's Cantonese enclaves/population and it is now slowly replacing Manhattan's Chinatown as the Cantonese cultural center of NYC. Originally Brooklyn's Chinatown in Sunset Park was a small satellite of Manhattan's Western Cantonese Chinatown, but its population has since grown due to increases in immigration and in the number of people moving from Manhattan.[73][74]

Fuzhouese-Cantonese relations

The Fuzhou immigration pattern started out in the 1970s very similarly like the Cantonese immigration during the late 1800s to early 1900s that had established Manhattan's Chinatown on Mott Street, Pell Street, and Doyers Street. Starting out as mostly men arriving first and then later on bringing their families over. The beginning influx of Fuzhou immigrants arriving during the 1980s and 1990s were entering into a Chinese community that was extremely Cantonese dominated. Due to the Fuzhou immigrants having no legal status and inability to speak Cantonese, many were denied jobs in Chinatown as a result causing many of them to resort to crimes to make a living that began to dominate the crimes going on in Chinatown. There was a lot of Cantonese resentment against Fuzhou immigrants arriving into Chinatown.[75][76][77][78][79][80] However, since gentrification has started happening in Manhattan's Chinatown since the 2000s, the Chinese population in this neighborhood is rapidly declining, with many residents moving to Queens and Brooklyn.

Demographics and culture

In 2000, most of Chinatown's residents came from Asia. That year, the number of residents was 84,840, and 66% of this people were Asian.[81]

Demographics

The census tabulation area for Chinatown is bounded to the north by Houston Street, to the east by Avenue B / Norfolk Street / Essex Street / Pike Street (in southbound order), to the south by Frankfort Street, and to the west by Bowery north of Canal Street and Centre Street south of it. Based on data from the 2010 United States Census, the population of Chinatown was 47,844, a change of -4,531 (-9.5%) from the 52,375 counted in 2000. Covering an area of 332.27 acres (134.46 ha), the neighborhood had a population density of 144 inhabitants per acre (92,000/sq mi; 36,000/km2).[2] The racial makeup of the neighborhood was 16.3% (7,817) White, 4.8% (2,285) African American, 0.1% (38) Native American, 63.9% (30,559) Asian, 0% (11) Pacific Islander, 0.2% (75) from other races, and 1.3% (639) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 13.4% (6,420) of the population.[3]

The racial composition of Chinatown changed substantially from 2000 to 2010, with the most significant changes being the increase in the White population by 42% (2,321), the decrease in the Asian population by 15% (5,461), and the decrease in the Hispanic / Latino population by 15% (1,121). The Black population decreased by 3% (62) and remained a small minority, while the very small population of all other races decreased by 21% (208).[82]

Chinatown lies in Manhattan Community District 3, which encompasses Chinatown, the East Village and the Lower East Side, bounded to the north by 14th Street and to the east by Fourth Avenue / Cooper Square / Bowery (in southbound order) north of Canal Street and Baxter Street / Pearl Street south of it. Community District 3 had 171,103 residents as of NYC Health's 2018 Community Health Profile, with an average life expectancy of 82.2 years.[83]:2, 20 This is higher than the median life expectancy of 81.2 for all New York City neighborhoods.[84]:53 (PDF p. 84) Most residents are adults: a plurality (35%) are between the ages of 25–44, while 25% are between 45–64, and 16% are 65 or older. The ratio of youth and college-aged residents was lower, at 13% and 11% respectively.[83]:2

As of 2017, the median household income in Community District 3 was $39,584,[85] though the median income in Chinatown individually was $68,657.[4] In 2018, an estimated 18% of Community District 3 residents lived in poverty, compared to 14% in all of Manhattan and 20% in all of New York City. One in twelve residents (8%) were unemployed, compared to 7% in Manhattan and 9% in New York City. Rent burden, or the percentage of residents who have difficulty paying their rent, is 48% in Community District 3, compared to the boroughwide and citywide rates of 45% and 51% respectively. Based on this calculation, as of 2018, Community District 3 is considered to be gentrifying: according to the Community Health Profile, the district was low-income in 1990 and has seen above-median rent growth up to 2010.[83]:7

Chinese cultural standards

Despite the more recently emerged large Fuzhou population, many of the Chinese businesses in Chinatown are still Cantonese owned and because of still the large Cantonese population on the Lower East Side, the Cantonese language still carries a strong presence in Chinatown including to the additional large influx of Cantonese speaking customers coming from other places to neighborhood on the weekends to do shopping and eat in restaurants even though Mandarin Chinese is rapidly sweeping Cantonese aside as the lingua franca of Chinatown,[44]:38[8] allowing Cantonese to continue to exert a significant level of influence upon the cultural standards and economic resources of Manhattan's Chinatown. The Cantonese dominated western section of Chinatown also continues to be the main busy Chinese business district.

As a result, it has influenced many Fuzhou people to learn the Cantonese dialect as well to maintain a job and to be able to bring more Cantonese customers as additional contributions to their businesses, especially large businesses like the Dim Sum restaurants on what is known as Little Fuzhou on East Broadway (小福州), the center of Fuzhou culture.[76][86][87] The Fuzhouese, the subgroup of non-Cantonese-speaking Chinese with the most interactions with Cantonese, also constitute the majority of non-native Cantonese-speaking Chinese. Many of the Fuzhou immigrants in the 1980s and early 1990s learned to speak Cantonese to maintain jobs and communicate with the Cantonese-speaking population. However, since the 2000s, the dominant Cantonese dialect has been uprooted by Mandarin Chinese, the national language of China and the lingua franca of many newer Chinese immigrants.[8]

A significant difference between the two separate Chinese provincial communities in Manhattan's Chinatown is that the Cantonese part of Chinatown not only serves Chinese customers but is also a tourist attraction, whereas the Fuzhou part of Chinatown caters less to tourists, but it is now slowly receiving tourists as well.[88][89] Bowery, Chrystie Street, Catherine Street, and Chatham Square encompass the approximate border zone between the Fuzhou and Cantonese communities in Manhattan's Chinatown.[65]:112

Unlike most other urban Chinatowns, Manhattan's Chinatown is both a residential area as well as commercial area. Many population estimates are in the range of 90,000 to 100,000 residents.[90][91][92][93] One analysis of census data in 2011 showed that Chinatown and heavily Chinese tracts on the Lower East Side had 47,844 residents in the 2010 census, a decrease of nearly 9% since 2000.[94]

Gentrification and decline in Chinese population

Currently, the rising prices of Manhattan real estate and high rents are also affecting Chinatown. Many new and poorer Chinese immigrants cannot afford their rents; as a result, most of the growth in new Chinese immigration has shifted to other Chinatowns in New York City, including the Flushing Chinatown and Elmhurst Chinatown in Queens; the Brooklyn Chinatown and its satellite Chinatowns in Brooklyn on Avenue U and in Bensonhurst; and to East Harlem in Upper Manhattan. Many apartments, particularly in the Lower East Side and Little Italy, which used to be affordable to new Chinese immigrants, are being renovated and then sold or rented at much higher prices. Building owners, many of them established Chinese-Americans, often find it in their best interest to terminate leases of lower-income residents with stabilized rents as property values rise.

By 2007, luxury condominiums began to spread from SoHo into Chinatown. Previously, Chinatown was noted for its crowded tenements and primarily Chinese residents. While some projects have targeted the Chinese community, the development of luxury housing has increased Chinatown's economic and cultural diversity.[95]

Since the early 2000s, there has been a continuously increasing number of buildings in Chinatown, neighboring Two Bridges, and the Lower East Side, taken over by new landlords and real estate developers, who then charged higher rents and/or demolished the buildings to build newer structures.[67] Often, whenever this happens, many Fuzhouese tenants are more likely to be evicted, especially in the Eastern Portion of Manhattan's Chinatown, where many of the apartment buildings hold the vast majority of Fuzhou tenant population due to the majority of Fuzhou people in legal risks such as illegal apartment subdivision; often excessive occupancy overcrowding, lack of leases, and lack of immigrant paperwork; these legal risks were often overlooked by the original, Chinese landlords. In addition, within recent years since the 2000s, there have been city officials inspecting apartment buildings and cracking down on illegally subdivided apartments and kicking out the occupants throughout Manhattan's Chinatown, however, the Fuzhou occupied apartments have been the primary main targets of these crackdowns and mostly in the eastern section of Manhattan's Chinatown where the Fuzhou population is primarily concentrated.

With tenants that have rent-stabilized leases, legal residency documents, no apartment subdivisions, and a lesser probability of subletting over capacity—most of whom are long-time Cantonese residents—it is usually harder for the newer landlords to be able to force these tenants out, especially including the western portion of Chinatown, which is still mainly Cantonese populated. However, newer landlords still continuously try find other loopholes to force them out.[96]

By 2009, many newer Chinese immigrants settled along East Broadway instead of the historic core west of Bowery. In addition Mandarin began to eclipse Cantonese as the predominant Chinese dialect in New York's Chinatown during the period. The New York Times says that the Flushing Chinatown now rivals Manhattan's Chinatown in terms of being a cultural center for Chinese-speaking New Yorkers' politics and trade.[8]

Current status as Chinese shopping business district

Despite the gentrification going on in the area and the decline in Chinese population and businesses and although there is an increasing influx of high-income hipster residents and businesses moving into the Chinatown neighborhood, it is still a large popular Chinese commercial shopping district, frequented by residents of the New York metropolitan area. An influx of tourists and visitors also come to Chinatown, including both non-Chinese and mainland Chinese. In addition, high-income professionals are moving into the area and patronizing Chinese businesses. All these customers contribute significantly to the profits of Chinese businesses.[97]

However, the distribution of consumer attractions and busy business sections are not equally concentrated throughout all of Chinatown. The western half of Chinatown (the original Cantonese Chinatown), known as Little Hong Kong/Guangdong, is the only section of Chinatown that is still a very busy Chinese shopping business district with many Cantonese and non-Asian consumers. Since the 2010s, there have been fewer consumers, causing many of the Chinese businesses to close and resulting in many of the remaining Chinese merchants struggling to make a profit. However, the eastern/southern part of Chinatown, known as Little Fuzhou has been the most primarily affected by the rapidly declining Chinese businesses and profits/consumers, due to the area's declining Fuzhou population, as well as the lack of tourists and there are now very few Fuzhou consumers from other parts of the New York metropolitan area coming to Manhattan's Chinatown. As a result, the Little Fuzhou section has become a primarily residential, increasingly gentrified area with the new residents being primarily white, and is increasingly becoming very unprofitable for new or existing Chinese businesses in this section of Chinatown.[97] Because of the uneven concentrations of the consumers and busy business sections between the two different portions of Chinatown, there is a high likelihood that the Cantonese portion of Chinatown will become the last remaining significant Chinese shopping business district. On the other hand, businesses in Little Fuzhou may be affected by the spread of gentrification from the nearby Lower East Side and East Village.[97][98]

Streetscape

Economy

Chinese greengrocers and fishmongers are clustered around Mott Street, Mulberry Street, Canal Street (by Baxter Street), and all along East Broadway (especially by Catherine Street). The Chinese jewelers' district is on Canal Street between Mott and Bowery. Due to the high savings rate among Chinese, there are many Asian and American banks in the neighborhood. Canal Street, west of Broadway (especially on the Northside), is filled with street vendors selling knock-off brands of perfumes, watches, and handbags. This section of Canal Street was previously the home of warehouse stores selling surplus/salvage electronics and hardware.

In addition, tourism and restaurants are major industries. The district boasts many historical and cultural attractions, and it is a destination for tour companies like Manhattan Walking Tour, Big Onion, NYC Chinatown Tours, and Lower East Side History Project.[99] Tour stops often include landmarks like the Church of the Transfiguration and the Lin Zexu and Confucius statues.[100] The enclave's many restaurants also support the tourism industry. The Manhattan Food Tours and New York Food Tours companies run programs taking visitors to the area's eateries for dishes like Shanghai Scallion Pancakes and wonton soup.[101] The Chinatown restaurant scene is large and vibrant, with more than 300 Chinese restaurants in the neighborhood providing employment. Notable and well-reviewed Chinatown establishments include Joe's Shanghai, Jing Fong, New Green Bo and Amazing 66.[102]

Other contributors to the economy include factories. The proximity of the fashion industry has kept some garment work in the local area, which at its peak employed 30,000 workers, though much of the garment industry has since moved to China. The local garment industry now concentrates on quick production in small volumes and piece work, which is generally done at the worker's home. Much of the population growth is due to immigration.

The September 11, 2001 attacks caused a decline in business for stores and restaurants in Chinatown. Chinatown was adversely affected by the attacks; being so physically close to Ground Zero, Chinatown saw a very slow return of tourism and business. Part of the reason was the NYPD closure of Park Row, one of two major roads linking the Financial District with Chinatown (the other being Centre Street). However, the area's economy, as well as tourism, have rebounded since then. A Chinatown business improvement district was established in 2011 despite opposition from business owners in the community.[94][103]

The neighborhood is home to several large Chinese supermarkets. In August 2011, a new branch of New York Supermarket opened on Mott Street in the central district of grocery and food shopping of Manhattan's Chinatown.[104] Just a block away from New York Supermarket, is a Hong Kong Supermarket located on the corner of Elizabeth and Hester Streets. These two supermarkets are amongst the largest Chinese supermarkets carrying all different food varieties within the long-time established Cantonese community in the western section of Manhattan's Chinatown.[105] A Hong Kong Supermarket at East Broadway and Pike Street burned down in 2009 and plans to construct a 91-room Marriott Hotel in its place resulted in community protests.[106] The New York Supermarkets chain, which also operates markets in Elmhurst and Flushing, settled with the New York State Attorney General in 2008 in which it paid back wages and overtime to workers.[107] Many of the Chinese restaurant menus in the U.S. are printed in Chinatown, Manhattan.[108]

Satellite Chinatowns

For a long time, Manhattan's Chinatown has always been the most largely concentrated Chinese population in NYC, which is 6% Chinese American overall. However, in recent years growing Chinese populations in the outer boroughs of NYC have tremendously outnumbered Manhattan's Chinese population.[109][110] Other New York City Chinese communities have been settled over the years, including that of Flushing in Queens, particularly along from Roosevelt Avenue to Main Street through Kissena Blvd.

Another Chinese community is located in Sunset Park in Brooklyn, particularly along 8th Avenue from 40th to 65th Streets. New York City's newer Chinatowns have recently sprung up in Elmhurst and Corona, Queens (which border each other and are part of the same Chinatown), on Avenue U in the Homecrest section of Brooklyn, as well as in Bensonhurst, also in Brooklyn. Outside of New York City proper, rapidly growing suburban Chinatowns are developing within the New York metropolitan area in nearby Edison, New Jersey and Nassau County, Long Island.[111]

While the composition of these satellite Chinatowns are as varied as the original, the political factions in the original Manhattan Chinatown (Tongs, Republic of China loyalists, People's Republic of China loyalists, and those apathetic) have led to some factionalization in the satellite Chinatowns.

Satellite Chinatowns' demographics

The Flushing Chinatown was spearheaded by many Chinese following the Handover of Hong Kong in 1997 as well as Taiwanese who used their considerable capital to buy out the land from the former residents. The Chinatowns of Flushing and Elmhurst are more middle class and were initially mainly small Taiwanese Mandarin-speaking enclaves, but have since grown very large and very diversified with Chinese migrants from many various regions from mainland China also often speaking Mandarin along with their regional dialects. Flushing is now the largest Chinatown of New York City including it has taken over as being the main Chinese cultural center due to the very high diversity of Chinese immigrants from many various regions of Mainland China and Taiwan.[112][113][114][115]

There are three major Brooklyn Chinatowns. Unlike the Chinese enclaves in Queens, which has a very high diversity of Chinese immigrants from various regions of Mainland China and Taiwan, the Brooklyn Chinatowns are very segregated into Cantonese dominated enclaves in Bensonhurst and Sheepshead Bay and the Fuzhou dominated enclave in Sunset Park, although with some significant limited population of long-time Cantonese residents. The Sunset Park Chinatown originally emerged as a small Cantonese enclave, but with the large influx of Fuzhou immigrants arriving into Sunset Park since the 2000s, it has grown into becoming the largest Fuzhou Chinatown of New York City, although some Cantonese people remain in the Sunset Park area.[116][117] The Bensonhurst and Sheepshead Bay Chinatowns are primarily Cantonese populated as a result of many of them migrating away from both Chinatowns of Manhattan and Brooklyn Sunset Park including new Cantonese immigration. Bensonhurst Chinatown's Chinese population is growing faster than that of Sunset Park as well as it is slowly becoming the largest Cantonese Chinatown in New York City. In addition, according to the 2010 census information, Bensonhurst including nearby neighborhood of Bath Beach in Brooklyn together now constitutes New York City's largest concentrated community of Hong Kong Residents with 3,723 in Bensonhurst and 1,049 in Bath Beach totaling together at 4,772 even though they are very heavily mixed in with the area's much larger Cantonese community that are dominantly populated by Cantonese speaking immigrants from Mainland China's Guangdong Province and although most of the Hong Kong residents are scattered in many other neighborhoods of New York City while only roughly about less than a quarter of New York City's Hong Kong residents reside in Bensonhurst/Bath Beach, however each other New York City neighborhood that may have very minor to significant numbers of Hong Kong residents have much lower concentrations of them than in Bensonhurst/Bath Beach. [118][119][120][121][122][123]

Buildings

For much of Chinatown's history, there were few unique architectural features to announce to visitors that they had arrived in the neighborhood (other than the language of the shop signs). In 1962, the Lieutenant Benjamin Ralph Kimlau Memorial archway at Chatham Square was erected in memorial of the Chinese-Americans who died in World War II, designed by local architect Poy Gum Lee (1900–1968).[124] This memorial bears calligraphy by the great Yu Youren 于右任 (1879–1964). A statue of Lin Zexu (林則徐), also known as Commissioner Lin, a Foochowese Chinese official who opposed the opium trade, is also located at the square; it faces uptown along East Broadway, now home to the bustling Fuzhou neighborhood and known locally as Fuzhou Street (Fúzhóu jiē 福州街).

More decorations and cultural institutions followed. In the 1970s, New York Telephone, then the local phone company, started capping the street phone booths with pagoda-like decorations. In 1976, the statue of Confucius in front of Confucius Plaza became a common meeting place. In the 1980s, banks that opened new branches and others that were renovating started to use Chinese traditional styles for their building facades. The Church of the Transfiguration, a national historic site built in 1815, stands off Mott Street. The Chinese American experience has been documented at the Museum of Chinese in America in Manhattan's Chinatown since 1980. In addition, Pearl River Mart, which opened in 1971, has become one of the more notable family-owned stores in Chinatown.

In 2010, Chinatown and Little Italy were listed in a single historic district on the National Register of Historic Places.[125]

Housing

The housing stock of Chinatown is still mostly composed of cramped tenement buildings, some of which are over 100 years old. It is still common in such buildings to have bathrooms in the hallways, to be shared among multiple apartments. A federally subsidized housing project, named Confucius Plaza, was completed on the corner of Bowery and Division Street in 1976. This 44-story residential tower block gave much needed new housing stock to thousands of residents. The building also housed a new public grade school, PS 124 (or Yung Wing Elementary). Besides being the first and largest affordable housing complex specifically available to the Chinatown population Confucius Plaza is also a cultural and institutional landmark, springing forth community organization, Asian Americans for Equality (AAFE), one of Chinatown's oldest political/community organizations, founded in 1974.

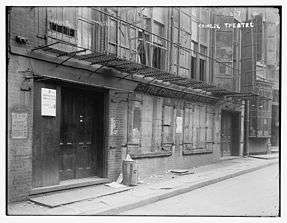

Chinese theaters

In the past, Chinatown had Chinese movie theaters that provided entertainment to the Chinese population. The first Chinese-language theater in the city was located at 5–7 Doyers Street from 1893 to 1911. The theater was later converted into a rescue mission for the homeless from Bowery. In 1903, the theater was the site of a fundraiser by the Chinese community for Jewish victims of a massacre in Kishinev.[126]

Among the theaters that existed in Chinatown in later years were the Sun Sing Theater under the Manhattan Bridge and the Pagoda Theater, both on the street of East Broadway, the Governor Theater on Chatham Square, the Rosemary Theater on Canal Street across the Manhattan Bridge, as well as the Music Palace on the Bowery, which was the last Chinese theater to close. Others have existed in different sections of Chinatown. The Chinese theaters also played movies with Chinese and English subtitles for the non-Chinese viewers, which were very often black Muslims that enjoyed movies with non-white heroes, Caucasian martial arts students and people who were film cognoscenti. During the 1970s, the Chinese theaters became less attractive due to increasing gang-violence. These theaters now have all closed because of more accessibility to videotapes, which were more affordable and provided more genres of movies and much later on DVDs and VCDs became available. Other factors such as, availability of Chinese cable channels, karaoke bars, and gambling in casinos began to provide other options for the Chinese to have entertainment also influenced the Chinese theaters to go out of business.[127][128][129][130]

Police and crime

Chinatown is patrolled by the 5th Precinct of the NYPD, located at 19 Elizabeth Street.[131] The 5th Precinct and the adjacent 7th Precinct ranked 58th safest out of 69 patrol areas for per-capita crime in 2010.[132] With a non-fatal assault rate of 42 per 100,000 people, Chinatown and the Lower East Side's rate of violent crimes per capita is less than that of the city as a whole. The incarceration rate of 449 per 100,000 people is higher than that of the city as a whole.[83]:8

The 5th Precinct has a lower crime rate than in the 1990s, with crimes across all categories that have decreased by 77.1% between 1990 and 2019. The precinct reported 6 murders, 14 rapes, 91 robberies, 210 felony assaults, 101 burglaries, 585 grand larcenies, and 16 grand larcenies auto in 2019.[133]

Fire safety

Chinatown is served by two New York City Fire Department (FDNY) fire stations:[134]

Health

Preterm and teenage births are less common in Chinatown and the Lower East Side than in other places citywide. In Chinatown and the Lower East Side, there were 82 preterm births per 1,000 live births (compared to 87 per 1,000 citywide), and 10.1 teenage births per 1,000 live births (compared to 19.3 per 1,000 citywide).[83]:11 Chinatown and the Lower East Side have a low population of residents who are uninsured. In 2018, this population of uninsured residents was estimated to be 11%, slightly less than the citywide rate of 12%.[83]:14

The concentration of fine particulate matter, the deadliest type of air pollutant, in Chinatown and the Lower East Side is 0.0089 milligrams per cubic metre (8.9×10−9 oz/cu ft), more than the city average.[83]:9 Twenty percent of Chinatown and Lower East Side residents are smokers, which is more than the city average of 14% of residents being smokers.[83]:13 In Chinatown and the Lower East Side, 10% of residents are obese, 11% are diabetic, and 22% have high blood pressure—compared to the citywide averages of 24%, 11%, and 28% respectively.[83]:16 In addition, 16% of children are obese, compared to the citywide average of 20%.[83]:12

Eighty-eight percent of residents eat some fruits and vegetables every day, which is about the same as the city's average of 87%. In 2018, 70% of residents described their health as "good," "very good," or "excellent," less than the city's average of 78%.[83]:13 For every supermarket in Chinatown and the Lower East Side, there are 18 bodegas.[83]:10

The nearest major hospital is NewYork-Presbyterian Lower Manhattan Hospital in the Civic Center area.[137][138]

Post offices and ZIP Codes

Chinatown is located within two primary ZIP Codes. The area east of Bowery is part of 10002, while the area west of Bowery is part of 10013.[139] The United States Postal Service operates two post offices in Chinatown:

- Chinatown Station – 6 Doyers Street[140]

- Knickerbocker Station – 128 East Broadway[141]

Education

Chinatown and the Lower East Side generally have a higher rate of college-educated residents than the rest of the city. A plurality of residents age 25 and older (48%) have a college education or higher, while 24% have less than a high school education and 28% are high school graduates or have some college education. By contrast, 64% of Manhattan residents and 43% of city residents have a college education or higher.[83]:6 The percentage of Chinatown and the Lower East Side students excelling in math rose from 61% in 2000 to 80% in 2011 and reading achievement increased from 66% to 68% during the same period.[142]

Chinatown and the Lower East Side's rate of elementary school student absenteeism is lower than the rest of New York City. In Chinatown and the Lower East Side, 16% of elementary school students missed twenty or more days per school year, less than the citywide average of 20%.[84]:24 (PDF p. 55)[83]:6 Additionally, 77% of high school students in Chinatown and the Lower East Side graduate on time, more than the citywide average of 75%.[83]:6

Schools

Residents are zoned to schools in the New York City Department of Education. PS 124, The Yung Wing School is located in Chinatown.[143] It was named after Yung Wing, the first Chinese person to study at Yale University.[144] PS 130 Hernando De Soto is located in Chinatown.[145] PS 184 Shuang Wen School, a bilingual Chinese-English School which opened in 1998, is a non-zoned school in proximity to Chinatown.[146]

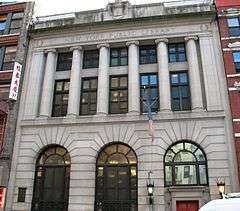

Library

The New York Public Library (NYPL) operates the Chatham Square branch at 33 East Broadway. The branch was founded in 1899; the current Carnegie library building opened in 1903 and was renovated in 2001. The four-story library contains a large Chinese collection, which has been housed at the library since 1911.[147]

Transportation

There are two New York City Subway stations that are directly in the neighborhood—Grand Street (B and D) and Canal Street (4, 6, <6>, J, N, Q, R, W, and Z)—although other stations are also nearby.[148] New York City Bus routes include M9, M15, M15 SBS, M22, M55, M103.[149]

The Manhattan Bridge connects Chinatown to Downtown Brooklyn. The FDR Drive runs along the East River, where the East River Greenway, a pedestrian walkway and bikeway, is also present.[150]

The major cultural streets are Mott Street and East Broadway; on the other hand, Canal Street, Allen Street, Delancey Street, Grand Street, East Broadway, and Bowery are the main traffic arteries.

There are multiple bike lanes in the area as well.[151]

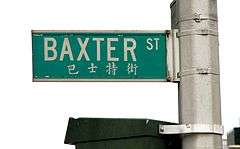

Street names in Chinese

All streets in Chinatown have Chinese names as well, which are noted on bilingual street signs in Chinatown.

| Street | Traditional Chinese | Pinyin | Jyutping |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allen Street | 亞倫街[152] | yǎ lún jiē | ngaa3 leon4 gaai1 |

| Baxter Street | 巴士特街[152] | bā shì tè jiē | baa1 si6 dak6 gaai1 |

| Bayard Street | 擺也街[152] | bǎi yě jiē | baai2 jaa5 gaai1 |

| Bowery | 包厘街[152] | bāo lí jiē | baau1 lei4 gaai1 |

| Broadway | 百老匯大道[152] | bǎilǎohuì dàdào | baak3 lou5 wui6 daai6 dou6 |

| Broome Street | 布隆街[152] | bù lóng jiē | bou3 lung4 gaai1 |

| Canal Street | 堅尼街[152] | jiān ní jiē | gin1 nei4 gaai1 |

| Catherine Street | 加薩林街[152] | jiā sà lín jiē | gaa1 saat3 lam4 gaai1 |

| Centre Street | 中央街[152] | zhōngyāng jiē | zung1 joeng1 gaai1 |

| Chambers Street | 錢伯斯街[152] | qián bó sī jiē | cin2 baak3 si1 gaai1 |

| Chatham Square | 且林士果[152] | qiě línshìguǒ | ce2 lam4 si6 gwo2 |

| Cherry Street | 車厘街 [152] | Chē lí jiē | ce1 lei4 gaai1 |

| Chrystie Street | 企李士提街[152] | qǐ lǐ shì tí jiē | kei5 lei5 si6 tai4 gaai1 |

| Delancey Street | 地蘭西街[152] | de lán xī jiē | dei6 laan4 sai1 gaai1 |

| Division Street | 地威臣街[152] | de wēi chén jiē | dei6 wai1 san4 gaai1 |

| Doyers Street | 宰也街[152] | zǎi yě jiē | zoi2 jaa5 gaai1 |

| East Broadway (Little Fuzhou) | 東百老匯 (小福州)[152] | dōng bǎilǎohuì

(xiǎo fúzhōu) |

dung1 baak3 lou5 wui6 |

| Eldridge Street | 愛烈治街[152] | ài liè zhì jiē | ngoi3 lit6 zi6 gaai1 |

| Elizabeth Street | 伊利莎白街[152] | yīlì shā bái jiē | ji1 lei6 saa1 baak6 gaai1 |

| Forsyth Street | 科西街[152] | kē xī jiē | fo1 sai1 gaai1 |

| Grand Street | 格蘭街[152] | gé lán jiē | gaak3 laan4 gaai1 |

| Henry Street | 顯利街[152] | xiǎn lì jiē | hin2 lei6 gaai1 |

| Hester Street | 喜士打街[152] | xǐ shì dǎ jiē | hei2 si6 daa2 gaai1 |

| Ludlow Street | 拉德洛街[152] | lā dé luò jiē | laai1 dak1 lok6 gaai1 |

| Madison Street | 麥地遜街[152] | mài dì xùn jiē | mak6 dei6 seon3 gaai1 |

| Market Street | 市場街[152] | shìchǎng jiē | si5 coeng4 gaai1 |

| Monroe Street | 門羅街[152] | mén luó jiē | mun4 lo4 gaai1 |

| Mosco Street | 莫斯科街[152] | mòsīkē jiē | mok6 si1 fo1 gaai1 |

| Mott Street (Little Hong Kong/Little Guangdong) | 勿街 (小香港)/(小廣東)[152] | wù jiē

(xiǎo xiānggǎng) (xiǎo guǎngdōng) |

mat6 gaai1 |

| Mulberry Street | 摩比利街[152] | mó bǐ lì jiē | mo1 bei2 lei6 gaai1 |

| Orchard Street | 柯察街[152] | kē chá jiē | o1 caat3 gaai1 |

| Park Row | 柏路[152] | bǎi lù | paak3 lou6 |

| Pell Street | 披露街[152] | pīlù jiē | pei1 lou6 gaai1 |

| Pike Street | 派街[152] | pài jiē | paai3 gaai1 |

| Rutgers Street | 羅格斯街[152] | Luó gé sī jiē | lo4 gaak3 si1 gaai1 |

| Water Street | 水街 | shuǐ jiē | seoi2 gaai1 |

| Worth Street | 窩夫街[152][153] | wō fū jiē | wo1 fu1 gaai1 |

| White Street | 白街 | bái jiē | baak6 gaai1 |

| South Street | 南街 | nán jiē | naam4 gaai1 |

See also

|

|

|

References

- "NYC Planning | Community Profiles". communityprofiles.planning.nyc.gov. New York City Department of City Planning. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- Table PL-P5 NTA: Total Population and Persons Per Acre - New York City Neighborhood Tabulation Areas*, 2010, Population Division - New York City Department of City Planning, February 2012. Accessed June 16, 2016.

- Table PL-P3A NTA: Total Population by Mutually Exclusive Race and Hispanic Origin - New York City Neighborhood Tabulation Areas*, 2010, Population Division - New York City Department of City Planning, March 29, 2011. Accessed June 14, 2016.

- "Chinatown neighborhood in New York". Retrieved March 18, 2019.

-

- "Chinatown New York City Fact Sheet" (PDF). www.explorechinatown.com. Retrieved April 11, 2016.

- Sarah Waxman. "The History of New York's Chinatown". Mediabridge Infosystems, Inc. Retrieved April 11, 2016.

Manhattan's Chinatown, the largest Chinatown in the United States and the site of the largest concentration of Chinese in the Western Hemisphere, is located on the Lower East Side.

- David M. Reimers (1992). Still the golden door: the Third ... – Google Books. ISBN 9780231076814. Retrieved April 11, 2016.

- Lawrence A. McGlinn, Department of Geography SUNY-New Paltz. "Beyond Chinatown: Dual immigration and the Chinese population of metropolitan New York City, 2000, Page 4" (PDF). Middle States Geographer, 2002, 35: 110–119, Journal of the Middle States Division of the Association of American Geographers. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 29, 2012. Retrieved April 11, 2016.

- David M. Reimers (1992). Still the golden door: the Third ... – Google Books. ISBN 9780231076814. Retrieved April 11, 2016.

- Marina Nazario (February 10, 2016). "I went on a tour of Manhattan's Chinatown and discovered some of the most unusual groceries I've ever seen". Business Insider. Archived from the original on February 15, 2016. Retrieved February 15, 2016.

- "American FactFinder - Results". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- Kirk Semple (October 21, 2009). "In Chinatown, Sound of the Future Is Mandarin". The New York Times. Retrieved April 11, 2016.

- Melia Robinson (May 27, 2015). "This is what it's like in one of the biggest and fastest-growing Chinatowns in the world". Business Insider. Retrieved July 30, 2017.

- City Council (October 15, 2011). "Chinatown BID approved despite opposition". citylandnyc.org. Retrieved September 7, 2012.

- Hay, Mark (July 12, 2010). "The Chinatown Question;". Capital. Archived from the original on November 1, 2010. Retrieved September 7, 2013.

- "A Journey through Chinatown". RK Chin. Retrieved September 7, 2013.

- "ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates 2013 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates New York-Newark-Bridgeport, NY-NJ-CT-PA CSA". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 4, 2015. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- Lawrence A. McGlinn, Department of Geography SUNY-New Paltz. "Beyond Chinatown: Dual immigration and the Chinese population of metropolitan New York City, 2000, p. 115" (PDF). Middle States Geographer, 2002, 35: 115, Journal of the Middle States Division of the Association of American Geographers. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 29, 2012. Retrieved September 30, 2013.

- Lawrence A. McGlinn, Department of Geography SUNY-New Paltz. "Beyond Chinatown: Dual immigration and the Chinese population of metropolitan New York City, 2000, Page 6" (PDF). Middle States Geographer, 2002, 35: 110–119, Journal of the Middle States Division of the Association of American Geographers. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 29, 2012. Retrieved December 2, 2012.

- Mays, Jeff (August 3, 2011). "East Harlem Tries to Serve Huge Influx of Chinese Residents - DNAinfo.com New York". Dnainfo.com. Archived from the original on February 24, 2013. Retrieved February 25, 2013.

- Barron, Laignee (August 8, 2011). "Chinese population climbs 200% in Harlem and East Harlem over 10 yrs". NY Daily News. New York. Retrieved February 25, 2013.

- Calvin Prashad (August 8, 2011). "Chinese American Population in Harlem NYC Surges". apaforprogress.org. Archived from the original on November 9, 2013. Retrieved February 25, 2013.

- Marc Santora (March 12, 2014). "At Least 3 Killed in Gas Blast on East Harlem Block; 2 Buildings Leveled". The New York Times. Retrieved March 12, 2014.

- J. DAVID GOODMAN (February 24, 2013). "Chinese Moving to East Harlem in a Quiet Shift From Downtown". The New York Times. Retrieved February 25, 2013.

- "ACS DEMOGRAPHIC AND HOUSING ESTIMATES 2017 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates Chinese alone - New York City, New York". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

- "Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2012 Supplemental Table 2". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

- "Kings County (Brooklyn Borough), New York QuickLinks". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on March 4, 2014. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

- "Queens County (Queens Borough), New York QuickLinks". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 25, 2016. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

- "Selected Population Profile in the United States 2014 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates – Queens County, New York Chinese alone". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 10, 2016.

- "Selected Population Profile in the United States 2014 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates – Kings County, New York Chinese alone". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 10, 2016.

- "Selected Population Profile in the United States 2014 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates – New York County, New York Chinese alone". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 10, 2016.

- "SELECTED POPULATION PROFILE IN THE UNITED STATES – 2014 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates – New York City – Chinese alone". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved September 20, 2015.

- "Chinatown Then and Now" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 12, 2015. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- Moss, Frank. The American Metropolis from Knickerbocker Days to the Present Time. London: The Authors' Syndicate, 1897. (pg. 403)

- Harlow, Alvin F. Old Bowery Days: The Chronicles of a Famous Street. New York and London: D. Appleton & Company, 1931. (pg. 392)

- Hemp, William H. New York Enclaves. New York: Clarkson M. Potter, 1975. (pg. 6) ISBN 0-517-51999-2

-

- Asbury, Herbert. The Gangs of New York: An Informal History of the New York Underworld. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1928. (pg. 278–279) ISBN 1-56025-275-8

- Worden, Helen. The Real New York: A Guide for the Adventurous Shopper, the Exploratory Eater and the Know-it-all Sightseer who Ain't Seen Nothin' Yet. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1932. (pg. 140)

- Wong, Bernard. Patronage, Brokerage, Entrepreneurship, and the Chinese Community of New York. New York: AMS Press, 1988. (pg. 31) ISBN 0-404-19416-8

- Lin, Jan. Reconstructing Chinatown: Ethnic Enclave, Global Change. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1998. (pg. 30–31) ISBN 0-8166-2905-6

- Taylor, B. Kim. The Great New York City Trivia & Fact Book. Nashville: Cumberland House Publishing, 1998. (pg. 20) ISBN 1-888952-77-6

- Ostrow, Daniel. Manhattan's Chinatown. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2008. (pg. 9) ISBN 0-7385-5517-7

- "Chinese - Searching for the Gold Mountain - Immigration...- Classroom Presentation | Teacher Resources - Library of Congress". www.loc.gov. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- Tchen, John Kuo Wei. New York Before Chinatown: Orientalism and the Shaping of American Culture, 1776–1882. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001. (pg. 82–83) ISBN 0-8018-6794-0

- Federal Writers' Project. New York City: Vol 1, New York City Guide. Vol. I. American Guide Series. New York: Random House, 1939. (pg. 104)

-

- Marcuse, Maxwell F. This Was New York!: A Nostalgic Picture of Gotham in the Gaslight Era. New York: LIM Press, 1969. (pg. 41)

- Chen, Jack. The Chinese of America. New York: Harper & Row, 1980. (pg. 258) ISBN 0-06-250140-2

- Hall, Bruce Edward. Tea That Burns: A Family Memoir of Chinatown. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2002. (pg. 37) ISBN 0-7432-3659-9

- "The Long Depression | History Today". www.historytoday.com. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- "Chinese Immigration to the United States - American Memory Timeline- Classroom Presentation | Teacher Resources - Library of Congress". www.loc.gov. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- Xinyang Wang (July 1, 1999). "Group Loyalties in the Workplace: The Chinese Immigrant Experience in New York City, 1890-1965". New York History. New York State Historical Association. 80 (3): 286–. ISSN 0146-437X. JSTOR 23182364.

- Wang, Wenfei, Shangyi Zhou, and C. Cindy Fan. "Growth and Decline of Muslim Hui Enclaves in Beijing" (Archive). Eurasian Geography and Economics, 2002, 43, No. 2, pp. 104-122. Cited page: 106.

- English, T.J. (1995). Born to Kill: America's Most Notorious Vietnamese Gang, and the Changing Face of Organized Crime. William Morrow & Co. ISBN 0-688-12238-8.

- Ko-Lin Chin (February 10, 2000). Chinatown Gangs: Extortion, Enterprise, and Ethnicity. Oxford University Press. pp. 8–. ISBN 978-0-19-513627-2. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- Patrick Radden Keefe (July 21, 2009). The Snakehead: An Epic Tale of the Chinatown Underworld and the American Dream. Random House Digital, Inc. ISBN 978-0-385-52130-7. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- Jan Lin (July 1, 1998). Reconstructing Chinatown: Ethnic Enclave, Global Change. University of Minnesota Press. pp. 52–. ISBN 978-0-8166-2905-3. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- New York Media, LLC (February 14, 1983). "New York Magazine". Newyorkmetro.com. New York Media, LLC: 38–. ISSN 0028-7369. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- "Columbus Park". New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. Retrieved June 20, 2014.

- Ronald Skeldon (1994). Reluctant Exiles?: Migration from Hong Kong and the New Overseas Chinese. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 256–. ISBN 978-962-209-334-8. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- Ming K. Chan; Gerard A. Postiglione (1996). The Hong Kong Reader: Passage to Chinese Sovereignty. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 174–. ISBN 978-1-56324-870-2. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- Michael S. Durham (March 21, 2006). National Geographic Traveler: New York, 2d Ed. National Geographic Books. pp. 71–. ISBN 978-0-7922-5370-9. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- Reid Bramblett (August 20, 2003). Frommer's Memorable Walks in New York. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 29–. ISBN 978-0-7645-5641-8. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- Isaac Bashevis Singer (April 1, 1981). A Crown of Feathers. Macmillan. pp. 135–. ISBN 978-0-374-51624-6. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- Time Inc (September 7, 1959). LIFE. Time Inc. pp. 36–. ISSN 0024-3019. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- Christopher Mele (March 15, 2000). Selling the Lower East Side: Culture, Real Estate, and Resistance in New York City. University of Minnesota Press. pp. 138–. ISBN 978-0-8166-3181-0. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- Xiaolan Bao (2001). Holding Up More Than Half the Sky: Chinese Women Garment Workers in New York City, 1948–92. University of Illinois Press. pp. 216–. ISBN 978-0-252-02631-7. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- Ralph Willett (1996). The Naked City: Urban Crime Fiction in the USA. Manchester University Press ND. pp. 68–. ISBN 978-0-7190-4301-7. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- John S. Dempsey; Linda S. Forst (January 1, 2011). An Introduction to Policing. Cengage Learning. pp. 266–. ISBN 978-1-111-13772-4. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- Jan Lin (September 20, 2005). The Urban Sociology Reader. Psychology Press. pp. 312–. ISBN 978-0-415-32342-0. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- Joyce Mendelsohn (September 1, 2009). The Lower East Side Remembered and Revisited: A History and Guide to a Legendary New York Neighborhood. Columbia University Press. pp. 29–. ISBN 978-0-231-14761-3. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- Greer, William R. Chinatown youth arrested in shooting that injured 7, The New York Times, May 25, 1985.

- 2 in a Chinatown Gang Convicted in Shootings, The New York Times, May 13, 1986.

- "Satellite Chinatowns Burgeon Throughout New York". The New York Times. September 14, 1986.

- "Why the Change? – Gentrification in NYC | Rosenberg 2018". eportfolios.macaulay.cuny.edu.

- Bonnie Tsui (August 11, 2009). American Chinatown: A People's History of Five Neighborhoods. Simon and Schuster. pp. 69–. ISBN 978-1-4165-5723-4. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- Ko-Lin Chin (December 9, 1999). Smuggled Chinese: Clandestine Immigration to the United States. Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1-56639-733-9. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- Zhao, Xiaojian (2010). The New Chinese America: Class, Economy, and Social Hierarchy. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780813549125. OCLC 642200646. Retrieved June 6, 2014.

- "A Tale of Two Chinatowns – Gentrification in NYC | Rosenberg 2018". eportfolios.macaulay.cuny.edu.

- Robbins, Liz (April 15, 2015). "With an Influx of Newcomers, Little Chinatowns Dot a Changing Brooklyn". The New York Times.

- Kwong, Peter (September 16, 2009). "Answers About the Gentrification of Chinatown". The New York Times. City Room (blog). Retrieved June 6, 2014.

- Bao, Xiaolan (2003). "Sweatshops in Sunset Park: A Variation of the Late Twentieth Century Chinese Garment Shops in New York City". In Daniel E. Bender; Richard A. Greenwald (eds.). Sweatshop USA: The American Sweatshop in Historical and Global Perspective. New York: Routledge. p. 133. ISBN 9780415935616. OCLC 52166009. Retrieved June 6, 2014.

- Jian-Cuo, World Journal, May 9, 2007, then translated from Chinese by Connie Kong (May 17, 2007). "High demand for illegal Chinatown apartments". New York Community Media Alliance. Archived from the original on August 2, 2012. Retrieved October 1, 2012.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- García, Ofelia; Fishman, Joshua A. (2002). The Multilingual Apple: Languages in New York City. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-017281-X.

- "The changing Chinatowns: Move over Manhattan, Sunset Park now home to most Chinese in NYC".

- Robbins, Liz (April 15, 2015). "With an Influx of Newcomers, Little Chinatowns Dot a Changing Brooklyn". The New York Times.

- Lii, Jane H. (June 12, 1994). "Neighborhood Report: Chinatown; Latest Wave of Immigrants Is Splitting Chinatown". The New York Times.

- Andrew Rosenberg; Martin Dunford (January 1, 2011). The Rough Guide to New York. Penguin. pp. 81–. ISBN 978-1-4053-8565-7. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- David Kyle; Rey Koslowski (May 11, 2001). Global Human Smuggling: Comparative Perspectives. JHU Press. pp. 236–. ISBN 978-0-8018-6590-9. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- Kenneth J. Guest (August 1, 2003). God in Chinatown: Religion and Survival in New York's Evolving Immigrant Community. NYU Press. pp. 11–. ISBN 978-0-8147-3154-3. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- Peter Kwong (July 30, 1996). The New Chinatown: Revised Edition. Macmillan. pp. 3–. ISBN 978-0-8090-1585-6. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- David W. Haines; Karen Elaine Rosenblum (1999). Illegal Immigration in America: A Reference Handbook. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 295–. ISBN 978-0-313-30436-1. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- Major Chinatown Census Statistics at a Glance

- "Race / Ethnic Change by Neighborhood" (Excel file). Center for Urban Research, The Graduate Center, CUNY. May 23, 2011. Retrieved March 22, 2020.

- "Lower East Side and Chinatown (Including Chinatown, East Village and Lower East Side)" (PDF). nyc.gov. NYC Health. 2018. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

- "2016-2018 Community Health Assessment and Community Health Improvement Plan: Take Care New York 2020" (PDF). nyc.gov. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. 2016. Retrieved September 8, 2017.

- "NYC-Manhattan Community District 3--Chinatown & Lower East Side PUMA, NY". Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- Let's Go Inc. (November 27, 2007). Let's Go USA 24th Edition. Macmillan. pp. 99–. ISBN 978-0-312-37445-7. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- "A journey through China town". Nychinatown.org. Retrieved November 15, 2009.

- Jan Lin (2011). The Power of Urban Ethnic Places: Cultural Heritage and Community Life. Taylor & Francis. pp. 226–. ISBN 978-0-415-87982-8. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- Xinyang Wang (2001). Surviving the City: The Chinese Immigrant Experience in New York City, 1890–1970. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 79–. ISBN 978-0-7425-0891-0. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- "New York Habitat Blog : Lower East Side". www.nyhabitat.com.

- Mano, D. Keith (April 24, 1988). "There's More To Chinatown". The New York Times.

- Kleinfield, N. R. (June 1, 1986). "Mining Chinatown's Mountain of Gold". The New York Times.

- "The Allure of Authentic New York". Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

- Berger, Joseph (September 21, 2011). "Chinatown Considers Business Improvement District". The New York Times. Retrieved September 21, 2011.

- Toy, Vivian S. "Luxury Condos Arrive in Chinatown." The New York Times. September 17, 2006. Retrieved on April 2, 2010.

-

- Lewis, Aidan (February 4, 2014). "The slow decline of American Chinatowns". BBC News.

- "Employment Agencies Leave Manhattan's Chinatown".

- Anna Merlan. "How Can New York Stop the City's Worst Landlords?". Village Voice.

- "Gov. Cuomo subpoenas landlord trying to evict rent-regulated tenants - New York's PIX11 / WPIX-TV". New York's PIX11 / WPIX-TV. August 21, 2014.

- "Rising Real Estate Prices Remake New York's Chinatown". VOA. Archived from the original on January 29, 2016. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- "Displacement Crisis in Chinatown".

- ERIN DURKIN (January 3, 2011). "Landlord tries to kick residents to curb". NY Daily News.

- "A Tale of Two Chinatowns – Gentrification in NYC | Rosenberg 2018".

- "– the Decline of East Broadway?".

- See:

- Big Onion Archived July 25, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- NYC Chinatown Tours

- Lower East Side History Project Archived April 24, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Big Onion, http://bigonion.com/description/index.html Archived July 25, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- New York Food Tours, Tastes of Chinatown, http://foodtoursofny.com/p/chinatown.html

- See:

- "Chinatown BID approved despite opposition". CityLand. October 15, 2011. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- "New Supermarket Opens on Mott Street in Chinatown". OurChinatown. Retrieved June 9, 2014.

- Travel New York City – Illustrated Guide and Maps. MobileReference. 2007. pp. 204–. ISBN 978-1-60501-028-1. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- Meng, Helen (October 31, 2011). "Chinatown gathering protests development". Voices of NY. Retrieved June 9, 2014.

- Greenhouse, Steven (December 9, 2008). "Supermarket to Pay Back Wages and Overtime". The New York Times.

- "20 Secrets of Your Local Chinese Takeout Joint". The Daily Meal. Archived from the original on September 24, 2017. Retrieved September 24, 2017.

- Ramirez, Jeanine (June 13, 2011). "Making Census Of It: As Brooklyn's Chinese-American Population Grows, Some Call For More Services". NY1. Archived from the original on August 17, 2011. Retrieved September 7, 2012.

- Khan, Shazia (July 20, 2011). "Making Census Of It: Chinatown No Longer Home To NYC's Largest Chinese Population". NY1. Archived from the original on August 19, 2012. Retrieved September 7, 2012.

- Lawrence A. McGlinn, Department of Geography SUNY-New Paltz. "Beyond Chinatown: Dual immigration and the Chinese population of metropolitan New York City, 2000, Page 6" (PDF). Middle States Geographer, 2002, 35: 110–119, Journal of the Middle States Division of the Association of American Geographers. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 29, 2012. Retrieved September 19, 2012.

- "Chinatown – Flushing, Queens – Little NYC".

- "Flushing, Queens: The Other Chinatown".