Park Row (Manhattan)

Park Row is a street located in the Financial District, Civic Center, and Chinatown neighborhoods of the New York City borough of Manhattan. The street runs east-west, sometimes called north-south because the western end is nearer to the Financial District. At the north end of Park Row is the confluence of Bowery, East Broadway, St. James Place, Oliver Street, Mott Street, and Worth Street at Chatham Square. At the street's south end, Broadway, Vesey Street, Barclay Street, and Ann Street intersect. The intersection includes a bus turnaround loop designated as Millennium Park. Park Row was once known as Chatham Street; it was renamed Park Row in 1886, a reference to the fact that it faces City Hall Park, the former New York Common.

| Coordinates | 40°42′40″N 74°0′30″W |

|---|---|

| West end | Broadway/Vesey Street/Ann Street |

| East end | Chatham Square |

Early history

In the late 18th century Eastern Post Road became the more important road connecting New York to Albany and New England. This section of the road which became Park Row was called Chatham Street,[1] a name that enters into the city's history on numerous occasions.

The tobacco industry in New York City got its start in 1760, when Pierre Lorillard opened a snuff factory on Chatham Street,[2] and in 1795, the Long Room of Abraham Martling's Tavern on Chatham Street was one of the first headquarters used by the Tammany Society and the Democratic-Republican Party on election days. Those who gathered there became known as "Martling Men", "Tammanyites" or "Bucktails", especially during the time that Tammany was attempting to wrest control of the party away from governor De Witt Clinton.[3] In the 1780s, Chatham Street was the site of the Tea Water Pump, a privately owned company which took water from Fresh Water Pond, the city's only supply of fresh water, and which remained purer longer than some of the other sources which drew from the pond.[4]

Chatham Street was also a center for entertainment. In 1798, Marc Isambard Brunel designed the 2,000-seat Park Theater on Chatham Street, intended to attract the upper classes of the city. The theater cost $130,000 to build, and tickets were 25 cents for seats in the gallery, and 50 cents in the orchestra. In the early 1800s, more taverns, theaters and small hotels on the street started to offer free entertain to attract customers to drink. These were called "free and easies", "varieties" or "vaudeville" and offered numerous different kinds of performances: comedy, dance, dramatic skits, magic, music, ventriloquism, and tellers of tall tales. New theaters such as the Chatham Theater sprang up as well to attract the overflow from the entertainment strip on the Bowery.[5] Boxing was also a popular entertainment. The Arena on Park Row packed in fans with its nightly presentation of "the manly art".[6]

Chatham Street was also the site of several anti-African American incidents, as in the Draft Riots of 1863, in which rioters were repulsed in their attempt to attack black waiters at Crook's Restaurant on the street.[7]

By the mid-19th century, Chatham Street had a bazaar-like atmosphere from the many used clothing shops and pawnbrokerages open by recently immigrated Jews from Germany and central Europe. This gave rise to anti-Semitic caricatures, although many New Yorkers could not distinguish German Jews from other Germans.[8]

Chatham Street was no stranger to poverty. In 1890, Jacob Riis revealed in How the Other Half Lives that over 9,000 homeless men lodged nightly on Chatham Street and the Bowery, between City Hall and the Cooper Union.[9]

Newspaper era

During the American Civil War, Joseph Pulitzer, later the publisher of the New York World newspaper, but then a recent immigrant from Hungary who had volunteered to serve in the Union cavalry, was thrown out of the elegant French's Hotel on Chatham Street at Frankfort Street. In 1888, Pulitzer bought the hotel and had it razed in order to build a new headquarters for the World. The New York World Building – also known as the "Pulitzer Building" – designed by George Browne Post, opened in 1890, with the governor and the mayor in attendance to celebrate the 309-foot tallest building in the world, topped by a gilded dome, the first building in the city to be taller than Trinity Church. Pulitzer's own semi-circular office was at the top of the building and featured frescoes on the ceiling, embossed leather walls, and three large windows.[10] The World folded in 1931, to become part of the New York World Telegram, then the New York World-Telegram & Sun, and, finally, in 1966, the New York World Journal Tribune, which represented the amalgamation of seven previously independent competing newspapers. The World Building became just another office building,[11] which was torn down in 1955 to make way for an expanded car ramp to the Brooklyn Bridge.

.jpg)

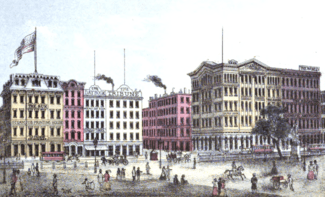

During the late 19th century, Chatham Street was nicknamed Newspaper Row, as most of New York City's newspapers located on the street to be close to City Hall.[12] Early in the 19th century most of the Manhattan portion of the street was suppressed, the Commons became City Hall Park, and the stub of a street was renamed Park Row.[13]

After the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge, Park Row was the site of the large Park Row Terminal for the elevated trains and cable-hauled shuttle cars which crossed the bridge. Service was gradually reduced from 1913 to 1940, and the terminal was demolished in 1944.[14] Until 1971, Park Row continued in a relatively straight path, except for a curved portion around the Brooklyn Bridge's ramps.[15] Between 1971 and 1973, a pedestrian plaza was built as part of 1 Police Plaza, Park Row was rerouted underneath the plaza, and its intersection with New Chambers Street and Duane Street was eliminated.[16]

Part of the southern section of the street was known as Printing House Square. Today, a statue of Benjamin Franklin by Ernst Plassman stands there, in front of the One Pace Plaza and 41 Park Row buildings of Pace University, holding a copy of his Pennsylvania Gazette, a reminder of what Park Row once was.

Structures

The New York Times was originally located at 113 Nassau Street in 1851. It moved to 138 Nassau Street in 1854, and in 1858 it moved a little more than one block away to 41 Park Row, possibly making it the first newspaper in New York City housed in a building built specifically for its use.[17] The New York Times Building, which was designed by George B. Post, was designated a New York City landmark in 1999.[18] The building is now used by Pace University.[19]

The New Yorker Staats-Zeitung moved to its own building at 17 Chatham Street at very nearly the same time as the Times moved into its new building.[20][21]

One of the first structures to be called a skyscraper, the Park Row Building (also known as 15 Park Row) is located at the western end of Park Row, opposite City Hall Park. Designed by noted architect R. H. Robertson, and built in 1896-99, It was designated a city landmark in 1999.[18] At 391 feet (119 m) tall it was the tallest office building in the world from 1899 until 1908, when it was surpassed by the Singer Building. The building is 29 stories tall, with 26 full floors and two, three-story cupolas. It has a frontage of 103 ft (31 m) on Park Row, 23 on Ann Street and 48 feet (15 m) on Theater Alley. The base of the building covers a land area of approximately 15,000 square feet (1,400 m2).

The Potter Building at 38 Park Row (145 Nassau Street) was built in 1882-86 and designated a New York City landmark in 1996. It was built after the owner's previous building on the site burned down. The Potter Building was converted into apartments between 1979 and 1981.[18]

The New York City Police Department is headquartered at 1 Police Plaza located on Park Row, across the street from the Manhattan Municipal Building[22] and Metropolitan Correctional Center.

Two apartment buildings of significance on Park Row are the Chatham Towers at no. 170, built in 1965 and designed by Kelly & Gruzen, which, according to the AIA Guide to New York City, makes a "strong architectural statement...[which] rouses great admiration and great criticism," and Chatham Green at 185 Park Row, built in 1961 and also designed by Kelly & Gruzen.[23]

Police Plaza closure

The segment of Park Row between Frankfort Street and Chatham Square is open only to MTA buses and government and emergency vehicles. The section of Park Row has been closed to civilian traffic since the September 11, 2001, attacks.[22] The NYPD asserts that this is necessary to protect its headquarters from a truck bomb attack. Chinatown residents are increasingly frustrated at the disruption caused by the closure of the thoroughfare, especially nearby residents. People who live nearby argue that the police department has placed a chokehold on an entire neighborhood and suggest One Police Plaza be moved from a residential area.[24] Members of the Civic Center Residents Coalition have been fighting the security perimeter around the building for years.

The NYPD has stated that it will not move despite the numerous complaints from residents, explaining that they had tried to alleviate the impact of the security measures by forbidding officers from parking in nearby public spaces and reopening a stairway that skirts the headquarter's south side and leads down to street level near the Brooklyn Bridge. The department also plans to redesign its guard booths and security barriers to make them more attractive, and was involved in efforts to convert two lanes of Park Row into a cycling and pedestrian greenway[22] which opened in June 2018.[25]

References

Notes

- Staff (June 22, 1893). "Outrages by 'Pullers in'" (PDF). The New York Times. p. 2.

About forty years ago the original Harris Cohen established a second-hand clothing store at the corner of Baxter Street and Park Row (then Chatham Street).

- Burrows & Wallace (1999), p.1046

- Burrows & Wallace (1999), pp.322,424

- Burrows & Wallace (1999), p.360

- Burrows & Wallace (1999), pp.375,404,642

- Burrows & Wallace (1999), p.755

- Burrows & Wallace (1999), p.890

- Burrows & Wallace (1999), pp.740,749

- Burrows & Wallace (1999), p.1182

- Burrows & Wallace (1999), p.1051

- Federal Writers' Project (1939). "New York City Guide". New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-60354-055-1. (Reprinted by Scholarly Press, 1976; often referred to as WPA Guide to New York City.), p.99

- Shepard, Richard F. (Marcdh 20, 1987) "Seeing the Evolution of New York City Through Artists' Eyes", The New York Times. Accessed February 24, 2008. "There are murals of City Hall, Newspaper Row, or Park Row and Nassau Street, at the century's turn the home of New York newspaperdom."

- Feirstein, Sanna (2001), Naming New York: Manhattan Places & How They Got Their Names, New York: New York University Press, p. 39, ISBN 978-0-8147-2712-6

- Sparberg, Andrew "Park Row" in Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (2010). The Encyclopedia of New York City (2nd ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 977. ISBN 978-0-300-11465-2.

- "New Brooklyn Bridge Car Routes". The New York Times. July 6, 1971. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- Goldberger, Paul (October 27, 1973). "New Police Building". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- Dunlap, David W. (November 14, 2001) "150th Anniversary: 1851–2001; Six Buildings That Share One Story", The New York Times. Accessed October 10, 2008. "Surely the most remarkable of these survivors is 113 Nassau Street, where the New-York Daily Times was born in 1851.... After three years at 113 Nassau Street and four years at 138 Nassau Street, The Times moved to a five-story Romanesque headquarters at 41 Park Row, designed by Thomas R. Jackson. For the first time, a New York newspaper occupied a structure built for its own use."

- New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission; Dolkart, Andrew S.; Postal, Matthew A. (2009). Postal, Matthew A. (ed.). Guide to New York City Landmarks (4th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-470-28963-1.

- White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot & Leadon, Fran (2010). AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- An Epitome of the New-Yorker Staats-Zeitung's Sixty-Five Years of Progress. 1899. Complimentary pamphlet prepared and distributed by the Staats-Zeitung to describe its history and new press capacity. This source indicates that the Staats-Zeitung was publishing from its building on Chatham Street no later than April 1858, and possibly as early as a year prior to that.

- Burrows & Wallace (1999), p.943

- Buckley, Cara. "Chinatown Residents Frustrated Over Street Closed Since 9/11", The New York Times, September 24, 2007. "The Police Department says that most of Park Row has to be blocked off to protect its headquarters, called One Police Plaza, against terrorist threats, particularly truck bombs."

- White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot & Leadon, Fran (2010). AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- Hogarty, Dave (September 24, 2007). "Park Row Paralysis". Gothamist. Archived from the original on May 21, 2011. Retrieved March 16, 2011.

- Spivack, Carol (June 22, 2018). "park-row-bike-pedestrian-paths-reopens-after-9-11-closure". patch. Retrieved July 3, 2018.

Bibliography

- Burrows, Edwin G. & Wallace, Mike (1999). Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-195-11634-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Park Row (Manhattan). |

- Park Row: A New York Songline – virtual walking tour