Kharkiv

Kharkiv (Ukrainian: Ха́рків, romanized: Chárkiv, pronounced [ˈxɑrkiu̯]), also known as Kharkov (Russian: Ха́рьков [ˈxarʲkəf])[6] is the second largest city in Ukraine.[7] In the northeast of the country, it is the largest city of the Slobozhanshchyna historical region. Kharkiv is the administrative centre of Kharkiv Oblast and of the surrounding Kharkiv Raion, though administratively it is incorporated as a city of oblast significance and does not belong to the raion.

Kharkiv (Харків) | |

|---|---|

| Ukrainian transcription(s) | |

| • National | Kharkiv |

| • ALA-LC | Kharkiv |

| • BGN/PCGN | Kharkiv |

| • Scholarly | Charkiv |

.png) Counterclockwise: Assumption Cathedral (big image), Kharkiv city council, National University of Kharkiv, Taras Shevchenko monument, Kharkiv Railway station, Derzhprom | |

Flag | |

| Nickname(s): The First Capital,[1][lower-alpha 1] Smart City | |

Kharkiv  Kharkiv | |

| Coordinates: 50°0′16″N 36°13′53″E | |

| Country | |

| Oblast | |

| Municipality | Kharkiv City Municipality |

| Founded | 1654[2] |

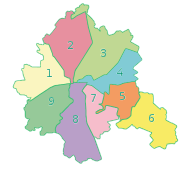

| Districts | List of 9[3]

|

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Hennadiy Kernes[4] |

| Area | |

| • City of regional significance | 350 km2 (140 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 152 m (499 ft) |

| Population (2019) | |

| • City of regional significance | 2,139,036 |

| • Density | 4,500/km2 (12,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,032,400 |

| Demonym(s) | Kharkivite[5] |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal code | 61001—61499 |

| Licence plate | AX, KX, ХА (old), 21 (old) |

| Sister cities | Belgorod, Bologna, Cincinnati, Kaunas, Lille, Moscow, Nizhny Novgorod, Nuremberg, Poznań, St. Petersburg, Tianjin, Jinan, Kutaisi, Varna, Rishon LeZion, Brno, Daugavpils |

| Website | city |

The city was founded in 1654 and after a humble beginning as a small fortress grew to be a major centre of Ukrainian industry, trade and culture in the Russian Empire. Kharkiv was the first capital of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, from December 1919 to January 1934, after which the capital relocated to Kiev.[8]

Presently, Kharkiv is a major cultural, scientific, educational, transport and industrial centre of Ukraine, with numerous museums, theatres and libraries, including the Annunciation and Dormition Cathedrals, the Derzhprom building in Freedom Square, and the National University of Kharkiv. Kharkiv was a host city for UEFA Euro 2012.

Industry plays a large role in Kharkiv's economy. Kharkiv's industry specializes primarily in machinery and in electronics. There are hundreds of industrial companies in the city, including the Morozov Design Bureau and the Malyshev Tank Factory (leaders in world tank production from the 1930s to the 1980s); Khartron (aerospace and nuclear power plants automation electronics); the Turboatom (turbines for hydro-, thermal- and nuclear-power plants), and Antonov (the multipurpose aircraft manufacturing plant).

Name

Some sources offer that the city was named after its near-legendary founder, Kharko (a diminutive form of the name Chariton, Ukrainian: Харитон,[2] or Zechariah, Ukrainian: Захарій).[9]

Among other names there are Charkow, Charkov, Zakharpolis.[10]

History

Cultural artifacts date back to the Bronze Age, as well as those of later Scythian and Sarmatian settlers. There is also evidence that the Chernyakhov culture flourished in the area from the second to the sixth centuries.

Establishment

The city was founded by re-settlers who were running away from the war that engulfed Right-bank Ukraine in 1654 (see Khmelnytsky Uprising).[2] The years before the region was a sparsely populated part of the Cossack Hetmanate.[11] The group of people came onto the banks of Lopan and Kharkiv rivers where an abandoned settlement stood.[12] According to archive documents, the leader of the re-settlers was otaman Ivan Kryvoshlyk.[2]

At first the settlement was self-governed under the jurisdiction of a voivode from Chuhuiv that is 40 kilometres (25 mi) to the east.[12] The first appointed voivode from Moscow was Voyin Selifontov in 1656 who started to build a local ostrog (fort).[12] At that time the population of Kharkiv was just over 1000, half of whom were local cossacks, while Selifontov brought along a Moscow garrison of another 70 servicemen.[12] The first Kharkiv voivode was replaced in two years after constantly complaining that locals refused to cooperate in building the fort.[12] Kharkiv also became the centre of the local Sloboda cossack regiment as the area surrounding the Belgorod fortress was being heavily militarized. With the resettlement of the area by Ukrainians it came to be known as Sloboda Ukraine, most of which was included under the jurisdiction of the Razryad Prikaz (Military Appointment) headed by a district official from Belgorod. By 1657 the Kharkiv settlement had a fortress[12] with underground passageways.

In 1658 Ivan Ofrosimov was appointed as the new voivode, who worked on forcing locals to kiss the cross to show loyalty to the Moscow tsar.[12] The locals led by their otaman Ivan Kryvoshlyk refused.[12] However, with the election of the new otaman Tymish Lavrynov the community (hromada) sent a request to the tsar to establish a local Assumption market, signed by deans of Kharkiv churches (the Assumption Cathedral and parish churches of Annunciation and Trinity).[12] Relationships with the neighboring Chuhuiv sometimes were non-friendly and often their arguments were pacified by force.[12] With the appointment of the third voivode Vasiliy Sukhotin was completely finished the construction of the city fort.[12]

Meanwhile, Kharkiv had become the centre of Sloboda Ukraine.[13]

Kharkiv Fortress

_ST_ASSUMPTION_ORTHODOX_CATHEDRAL_IN_CITY_OF_KHARKIV_STATE_OF_UKRAINE_PHOTOGRAPH_BY_VIKTOR_O_LEDENYOV_20160616.jpg)

_VIEW_ON_PEDESTRIAN_BRIDGE_OVER_KHARKIV_RIVER_IN_CITY_OF_KHARKIV_STATE_OF_UKRAINE_PHOTOGRAPH_BY_VIKTOR_O_LEDENYOV_20160616.jpg)

The Kharkiv Fortress was erected around the Assumption Cathedral and its castle was at University Hill.[12] It was between today's streets: vulytsia Kvitky-Osnovianenko, Constitution Square, Rose Luxemburg Square, Proletarian Square, and Cathedral Descent.[12] The fortress had 10 towers: Chuhuivska Tower, Moskovska Tower, Vestovska Tower, Tainytska Tower, Lopanska Corner Tower, Kharkivska Corner Tower and others.[12] The tallest was Vestovska, some 16 metres (52 ft) tall,[12] while the shortest one was Tainytska which had a secret well 35 metres (115 ft) deep.[12] The fortress had the Lopanski Gates.[12]

In 1689 the fortress was expanded and included the Saint-Pokrov Cathedral and Monastery which was baptized[12] and became the center of local eparchy. Coincidentally in the same year in the vicinity of Kharkiv in Kolomak, Ivan Mazepa was announced the Hetman of Ukraine.[12] Next to the Saint-Pokrov Cathedral was located the Kharkiv Collegiate that was transferred from Belgorod to Kharkiv in 1726.[12]

In the Russian Empire

In the course of the administrative reform carried out in 1708 by Peter the Great, the area was included into Kiev Governorate. Kharkiv is specifically mentioned as one of the towns making a part of the governorate.[14] In 1727, Belgorod Governorate was split off, and Kharkiv moved to Belgorod Governorate. It was the center of a separate administrative unit, Kharkiv Sloboda Cossack regiment. The regiment at some point was detached from Belgorod Governorate, then attached to it again, until in 1765, Sloboda Ukraine Governorate was established with the seat in Kharkiv.[15]

Kharkiv University was established in 1805 in the Palace of Governorate-General.[12] Alexander Mikolajewicz Mickiewicz, brother of Adam Mickiewicz was a professor of law in the university, another celebrity Goethe searched for instructors for the school.[12] In 1906 Ivan Franko received a doctorate in Russian linguistics here.[12][16]

The streets were first cobbled in the city centre in 1830.[17] In 1844 the 90 metres (300 ft) tall Alexander Bell Tower was built next to the first Assumption Cathedral, which on November 16, 1924 was transformed into a radio tower.[12] A system of running water was established in 1870. The Cathedral Descent at one time carried the name of another local trader Vasyl Ivanovych Pashchenko-Tryapkin as Pashchenko Descent.[12] Pashchenko even leased a space to the city council (duma) and was the owner of the city "Old Passage", the city's biggest trade center.[12] After his death in 1894 Pashchenko donated all his possessions to the city.[12]

Kharkiv became a major industrial centre and with it a centre of Ukrainian culture. In 1812, the first Ukrainian newspaper was published there. One of the first Prosvitas in Eastern Ukraine was also established in Kharkiv. A powerful nationally aware political movement was also established there and the concept of an Independent Ukraine was first declared there by the lawyer Mykola Mikhnovsky in 1900.

Soon after the Crimean War, in 1860–61 number of hromada societies sprung up across the Ukrainian cities including Kharkiv.[18] Among the most prominent hromada members in Kharkiv was Oleksandr Potebnia, a native of Sloboda Ukraine.[18] Beside the old hromada, in Kharkiv also existed several student hromadas members of which were future political leaders of Ukraine such as Borys Martos, Dmytro Antonovych and many others.[18] One of the University of Kharkiv graduates Oleksandr Kovalenko was one of initiators of the mutiny on Russian battleship Potemkin being the only officer who supported the in-rank sailors.

Since April 1780 it was an administrative centre of Kharkov uyezd.

The Red October and the Soviet period

_DERZHPROM_BUILDING_IN_CITY_OF_KHARKIV_STATE_OF_UKRAINE_PHOTOGRAPH_BY_VIKTOR_O_LEDENYOV_20160621.jpg)

Bolshevik Baltin in the "Chronicle of the Revolution" (Russian: Летопись Революции) noted that during the World War I in December 1914 Kharkiv experienced the most eerie Russian chauvinism (see, Great Russian chauvinism) which knew no limits when Russian ultra-nationalist Black Hundreds were assisted by a local police.[19] Baltin also stated that at that time the Kharkiv Locomotive Factory (employing 6,000 workers) was considered a "citadel of revolutionary movement"[19] yet due to pressure of the local police and the Russian nationalists the revolutionary life was completely suppressed.[19] In January 1915 the Kharkiv Bolshevik organization was accounted of no more than 10 people.[19] The Bolshevik organization in Kharkiv was revived after arrival of Aleksei Medvedev, Nikolay Lyakhin (Petrograd Bolsheviks) and Maksimov and Maria Skobeeva (Moscow Bolsheviks).[19] Following the Russian defeat during Gorlice–Tarnów Offensive and start of the Great Retreat, to Kharkiv from Riga was evacuated a plant of the Public Company of Electricity (Russian: Всеобщая Компания Электричества) with 4,000 workers.[19]

Baltin also pointed that national oppression during the war had increased and from it suffered especially Ukrainians.[19] With declaration of the war, there were closed all Ukrainian language newspapers and other periodicals.[19] During the "Great Retreat", the local pro-Ukrainian socialist-democrats managed to receive permission on publication of Ukrainophone newspaper "Slovo".[19] It was the first newspaper in Ukrainian language after a year of hiatus.[19] But soon the city administration fined the publisher of the newspaper, after which no other publisher wanted to print the newspaper.[19]

When the Tsentralna Rada announced the establishment of the Ukrainian People's Republic in November 1917 it envisioned the Sloboda Ukraine Governorate to be part of it.[2] In December 1917 Kharkiv became the first city in Ukraine occupied by the Soviet troops of Vladimir Antonov-Ovseyenko.[20] The Bolsheviks in the Tsentralna Rada moved to Kharkiv shortly after to make it their stronghold and formed their own Rada on 13 December 1917.[20][21] By February 1918 Bolshevik forces had captured much of Ukraine.[22] In February 1918 Kharkiv became the capital of the Donetsk-Krivoy Rog Soviet Republic; but this entity was disbanded six weeks later.[23] In April 1918 the German army occupied Kharkiv.[24] And according to the February 1918 Treaty of Brest-Litovsk between the Ukrainian People's Republic and the Central Powers it became part of the Ukrainian People's Republic.[25] Early January 1919 Bolshevik forces captured Kharkiv.[13] Mid-June 1919 Anton Denikin's White movement Volunteer Army captured the city.[26] In December 1919 the Bolshevik Red Army recaptured Kharkiv.[27]

Prior to the formation of the Soviet Union, Bolsheviks established Kharkiv as the capital of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (from 1919 to 1934) in opposition to the Ukrainian People's Republic with its capital of Kiev.[28]

According to linguist George Shevelov, in the early 1920s the share of secondary schools teaching in the Ukrainian language was lower than the share of the Kharkiv Oblasts ethnic Ukrainian population,[29] even though the Soviet Union had ordered that all schools in the Ukrainian SSR should be Ukrainian speaking (as part of its Ukrainization policy).[30]

As the country's capital, it underwent intense expansion with the construction of buildings to house the newly established Ukrainian Soviet government and administration. Derzhprom was the second tallest building in Europe and the tallest in the Soviet Union at the time with a height of 63 metres (207 ft).[31] In the 1920s, a 150 metres (490 ft) wooden radio tower was built on top of the building. The Roentgen Institute was established in 1931.[32] During the interwar period the city saw the spread of architectural constructivism.[12] One of the best representatives of it was the already mentioned Derzhprom, the Building of the Red Army, the Ukrainian Polytechnic Institute of Distance Learning (UZPI), the City Council building, with its massive asymmetric tower, the central department store that was opened on the 15th Anniversary of the October Revolution.[12] The same year on November 7, 1932 the building of Noblemen Assembly was transformed into the building of All-Ukrainian Central Executive Committee.[12][33][34]

In 1928, the SVU (Union for the Freedom of Ukraine) process was initiated and court sessions were staged in the Kharkiv Opera (now the Philharmonia) building. Hundreds of Ukrainian intellectuals were arrested and deported.

In the early 1930s, the Holodomor famine drove many people off the land into the cities, and to Kharkiv in particular, in search of food. Many people died and were secretly buried in mass graves in the cemeteries surrounding the city.

In 1934 hundreds of Ukrainian writers, intellectuals and cultural workers were arrested and executed in the attempt to eradicate all vestiges of Ukrainian nationalism in Art. The purges continued into 1938. Blind Ukrainian street musicians were also gathered in Kharkiv and murdered by the NKVD.[35] In January 1934 the capital of the Ukrainian SSR was moved from Kharkiv to Kiev.[8]

During April and May 1940 about 3,900 Polish prisoners of Starobelsk camp were executed in the Kharkiv NKVD building, later secretly buried on the grounds of an NKVD pansionat in Pyatykhatky forest (part of the Katyn massacre) on the outskirts of Kharkiv.[36] The site also contains the numerous bodies of Ukrainian cultural workers who were arrested and shot in the 1937–38 Stalinist purges.

German occupation

During World War II, Kharkiv was the site of several military engagements (see below). The city was captured and recaptured by Nazi Germany on 24 October 1941;[37][38] there was a disastrous Red Army offensive that failed to capture the city in May 1942;[39][40] the city was successfully retaken by the Soviets on 16 February 1943, captured for a second time by the Germans on 15 March 1943 and then finally retaken on 23 August 1943. Seventy percent of the city was destroyed and tens of thousands of the inhabitants were killed. Kharkiv, the third largest city in the Soviet Union, was the most populous city in the Soviet Union captured by the Germans, since in the years preceding World War II, Kiev was by population the smaller of the two.

The significant Jewish population of Kharkiv (Kharkiv's Jewish community prided itself with the second largest synagogue in Europe) suffered greatly during the war. Between December 1941 and January 1942, an estimated 15,000 Jews were killed and buried in a mass grave by the Germans in a ravine outside of town named Drobytsky Yar.[41]

During World War II, four battles took place for control of the city:

- First Battle of Kharkov

- Second Battle of Kharkov

- Third Battle of Kharkov

- Fourth Battle of Kharkov (see also Operation Polkovodets Rumyantsev)

Before the occupation, Kharkiv's tank industries were evacuated to the Urals with all their equipment, and became the heart of Red Army's tank programs (particularly, producing the T-34 tank earlier designed in Kharkiv). These enterprises returned to Kharkiv after the war, and continue to produce tanks.

Of the population of 700,000 that Kharkiv had before the start of World War II, 120,000 became Ost-Arbeiter (slave worker) in Germany, 30,000 were executed and 80,000 starved to death during the war.[13]

Post-World War II

In the post-World War II period, many of the destroyed homes and factories were rebuilt. The city was planned to be rebuilt in the style of Stalinist Classicism.[12]

An airport was built in 1954. Following the war, Kharkiv was the third largest scientific and industrial centre in the former USSR (after Moscow and Leningrad).

In 1975 Kharkiv subway was opened.

In independent Ukraine

By its territorial expansion on September 6, 2012 the city increased its area from about 310 to 350 square kilometres (120 to 140 sq mi).[42]

A well-known landmark of Kharkiv is the Freedom Square (Ploshcha Svobody formerly known as Dzerzhinsky Square), which is the ninth largest city square in Europe, and the 28th largest square in the world.

There is an underground rapid-transit system (metro) with about 38.7 km (24 mi) of track and 30 stations. The newest underground station, Peremoha, was opened on 19 August 2016. All the underground stations have very distinctive architecture.

Kharkiv was a host city for UEFA Euro 2012, and hosted three group soccer matches at the reconstructed Metalist Stadium.

A large number of Orthodox cathedrals were built in Kharkiv in the 1990s and 2000s. For example, the Myrrh Bringing Wives Orthodox cathedral, the St. Vladimir Orthodox cathedral, St. Tamara Orthodox cathedral, etc.

In 2007, the city's Vietnamese minority built the largest Buddhist temple in Europe on a 1 hectare plot with a monument to Ho Chi Minh.[43]

Gorky Park was fully renovated in the 2000s, having a big number of modern attractions, a lake with lilies and sport facilities to play tennis, football, beach volleyball, and basketball.

Feldman Park was created in recent years, containing a big collection of animals, horses, etc.

During the Euromaidan events, pro-Russian activists raised the Russian flag above the regional administration building and declared the Kharkov People's Republic. The uprising was quelled in less than two days due to rapid reaction of the Ukrainian security forces under then Ukrainian Interior Minister Arsen Avakov and Stepan Poltorak the then acting commander of the Ukrainian Internal Forces. In addition, a special forces unit from Vinnytsia was sent to the city to crush the separatists. The mayor of the city, Hennadiy Kernes, who supported the Orange Revolution but later joined the Party of Regions, decided to side with the Ukrainian government. 2014 to 2016 saw a series of terror attacks.

Geography

Kharkiv is located at the banks of the Kharkiv, Lopan, and Udy rivers, where they flow into the Seversky Donets watershed in the north-eastern region of Ukraine.

Historically, Kharkiv lies in the Sloboda Ukraine region (Slobozhanshchyna also known as Slobidshchyna) in Ukraine, in which it is considered to be the main city.

The approximate dimensions of city of Kharkiv are: from the North to the South — 24.3 km; from the West to the East — 25.2 km.

Based on Kharkiv's topography, the city can be conditionally divided into four lower districts and four higher districts.

The highest point above sea level in Pyatikhatky in Kharkiv is 202m, the lowest point above sea level in Novoselivka in Kharkiv is 94m.

Kharkiv lies in the large valley of rivers of Kharkiv, Lopan', Udy, and Nemyshlya. This valley lies from the North West to the South East between the Mid Russian highland and Donetsk lowland. All the rivers interconnect in Kharkiv and flow into the river of Northern Donets. A special system of concrete and metal dams was designed and built by engineers to regulate the water level in the rivers in Kharkiv.

Kharkiv has a large number of green city parks with a long history of more than 100 years with very old oak trees and many flowers. Gorky park, or Maxim Gorky Central Park for Culture and Recreation, is Kharkiv's largest public garden. The park has nine areas: children, extreme sports, family entertainment, a medieval area, entertainment center, French park, cable car, sports grounds, retro park.

Climate

Kharkiv's climate is humid continental (Köppen climate classification Dfb) with cold, snowy winters and dry and hot summers.

The city has rather sunny, warm summers which, however, are relatively mild compared to temperatures in South European regions, due to the region's lower elevation, proximity to the Black Sea, and the city's latitude.

Kharkiv has relatively long and cold winters.

The average rainfall totals 513 mm (20 in) per year, with the most in June and July.

| Climate data for Kharkiv, Ukraine (1981−2010, extremes 1936–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 11.1 (52.0) |

14.6 (58.3) |

21.8 (71.2) |

30.5 (86.9) |

34.5 (94.1) |

39.8 (103.6) |

38.4 (101.1) |

39.8 (103.6) |

34.5 (94.1) |

29.3 (84.7) |

20.3 (68.5) |

13.4 (56.1) |

39.8 (103.6) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −2.2 (28.0) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

4.3 (39.7) |

14.0 (57.2) |

20.8 (69.4) |

24.3 (75.7) |

26.4 (79.5) |

25.7 (78.3) |

19.4 (66.9) |

12.0 (53.6) |

3.6 (38.5) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

12.1 (53.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −4.6 (23.7) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

0.7 (33.3) |

9.2 (48.6) |

15.5 (59.9) |

19.2 (66.6) |

21.3 (70.3) |

20.3 (68.5) |

14.4 (57.9) |

7.9 (46.2) |

0.9 (33.6) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

8.1 (46.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −7.0 (19.4) |

−7.3 (18.9) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

4.6 (40.3) |

10.3 (50.5) |

14.2 (57.6) |

16.2 (61.2) |

14.9 (58.8) |

9.8 (49.6) |

4.3 (39.7) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

−5.9 (21.4) |

4.2 (39.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −35.6 (−32.1) |

−29.8 (−21.6) |

−32.2 (−26.0) |

−11.4 (11.5) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

2.2 (36.0) |

5.7 (42.3) |

2.2 (36.0) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

−9.1 (15.6) |

−20.9 (−5.6) |

−30.8 (−23.4) |

−35.6 (−32.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 36 (1.4) |

33 (1.3) |

33 (1.3) |

34 (1.3) |

50 (2.0) |

61 (2.4) |

60 (2.4) |

42 (1.7) |

47 (1.9) |

45 (1.8) |

41 (1.6) |

36 (1.4) |

517 (20.4) |

| Average rainy days | 10 | 8 | 10 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 13 | 10 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 143 |

| Average snowy days | 19 | 18 | 12 | 2 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.03 | 2 | 9 | 18 | 80 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 86 | 83 | 77 | 66 | 61 | 65 | 65 | 63 | 70 | 78 | 86 | 87 | 74 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 51 | 65 | 108 | 162 | 238 | 263 | 273 | 247 | 185 | 124 | 47 | 31 | 1,794 |

| Source 1: Pogoda.ru.net[44] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (sun only 1961–1990)[45] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

- Architecture in the city center of Kharkiv

_-_Ukraine_-_10_(30095278938).jpg)

.jpg)

Governance

Legal status and local government

The Mayor of Kharkiv and the City Council govern all the business and administrative affairs in the City of Kharkiv.

The Mayor of Kharkiv has the executive powers; the City Council has the administrative powers as far as the government issues are concerned.

The Mayor of Kharkiv is elected by direct public election in Kharkiv every four years.

The City Council is composed of elected representatives, who approve or reject the initiatives on the budget allocation, tasks priorities and other issues in Kharkiv. The representatives to the City Council are elected every four years.

The mayor and city council hold their regular meetings in the City Hall in Kharkiv.

Politics

The 2014 pro-Russian unrest in Ukraine affected Kharkiv but to a lesser extent than in neighbouring Donbass, where tensions led to armed conflict.[46] On 2 March 2014, a Russian "tourist" from Moscow replaced the Ukrainian flag with a Russian flag on the Kharkiv regional state administration building.[47] Five days later, pro-Russian protestors occupied the building and unilaterally declared independence from Ukraine as the "Kharkov People's Republic".[48] The next day, the building was retaken by Ukrainian special forces.[49] Doubts arose about the local origin of the protestors after they initially stormed an opera and ballet theatre believing it was the city hall.[50] On 13 April, some pro-Russian protesters again made it inside the Kharkiv regional state administration building.[51] Later on 13 April, the building permanently returned to full Ukrainian control.[48][49][51][52][53][54][55] Violent clashes resulted in the severe beating of at least 50 pro-Ukrainian protesters in attacks by pro-Russian protesters.[51][54]

Kharkiv returned to relative calm by 30 April.[56] Relatively peaceful demonstrations continued to be held, with "pro-Russian" rallies gradually diminishing and "pro-Ukrainian unity" demonstrations growing in numbers.[57][58][59] On 28 September, activists dismantled Ukraine's largest monument to Lenin at a pro-Ukrainian rally in the central square.[60] Polls conducted from September to December 2014 found little support in Kharkiv for joining Russia.[62]

From early November until mid-December, Kharkiv was struck by seven non-lethal bomb blasts. Targets of these attacks included a rock pub known for raising money for Ukrainian forces, a hospital for Ukrainian forces, a military recruiting centre, and a National Guard base.[63] According to SBU investigator Vasyliy Vovk, Russian covert forces were behind the attacks, and had intended to destabilize the otherwise calm city of Kharkiv.[64]

On 8 January 2015 five men wearing balaclavas broke into an office of (the volunteer group aiding refugees from Donbass) Station Kharkiv.[65] Simultaneously with physical threats the men demanded to hear the political position of Station Kharkiv.[65] After having been given an answer, the men apologized and left.[65]

On Sunday 22 February 2015, there was a terrorist bomb attack on a march to commemorate people who died in the Euromaidan protests in 2014. The bomb killed two, and wounded nine. The authorities launched an anti-terrorist operation.[66] The terrorists claimed that it was a false flag attack.[67] Kharkiv has experienced more non-lethal small bombings since 22 February 2015 targeting army fuel tanks, an unoccupied passenger train and a Ukrainian flag in the city centre.[68]

On 23 September 2015, 200 people in balaclavas and camouflage picketed the house of former governor Mykhailo Dobkin, and then went to Kharkiv town hall, where they tried to force their way through the police cordon. At least one tear gas grenade was used. The rioters asked the mayor, Hennadiy Kernes, to come out.[69][70]

Administrative divisions

While Kharkiv is the administrative centre of the Kharkiv Oblast (province), the city affairs are managed by the Kharkiv Municipality. Kharkiv is a city of oblast subordinance.

|

|

The territory of Kharkiv is divided into 9 administrative raions (districts), till February 2016 they were named for people, places, events, and organizations associated with early years of the Soviet Union but many were renamed in February 2016 to comply with decommunization laws.[3] Also, owing to this law, over 200 streets have been renamed in Kharkiv since 20 November 2015.[71]

- Kholodnohirskyi (Ukrainian: Холодногірський район, Cold Mountain; namesake: the historic name of the neighbourhood[73]) (formerly Leninskyi; namesake: Vladimir Lenin)

- Shevchenkivskyi (Ukrainian: Шевченківський район); namesake: Taras Shevchenko (formerly Dzerzhynskyi; namesake Felix Dzerzhinsky)

- Kyivskyi (Ukrainian: Київський район); namesake: Kiev (formerly Kahanovychskyi; namesake: Lazar Kaganovich)

- Moskovskyi (Ukrainian: Московський район); namesake: Moscow

- Nemyshlianskyi (Ukrainian: Немишлянський район) (formerly Frunzensky: namesake: Mikhail Frunze[72]);

- Industrialnyi (Ukrainian: Індустріальний район) (formerly Ordzhonikidzevskyi; namesake: Sergo Ordzhonikidze)

- Slobidskyi (Ukrainian: Слобідський район) (formerly Kominternіvsky[72]); namesake: Sloboda Ukraine

- Osnovianskyi (Ukrainian: Основ'янський район) (formerly Chervonozavodsky[72]); namesake: Osnova, a city neighborhood

- Novobavarskyi (Ukrainian: Новобаварський район) (formerly Zhovtnevy[72]); namesake: Nova Bavaria, a city neighborhood

Demographics

| Year | Pop. |

|---|---|

| 1660[74] | 1,000 |

| 1788[75] | 10,742 |

| 1850[76] | 41,861 |

| 1861[76] | 50,301 |

| 1901[76] | 198,273 |

| 1916[77] | 352,300 |

| 1917[78] | 382,000 |

| 1920[77] | 285,000 |

| 1926[77] | 417,000 |

| 1939[79] | 833,000 |

| 1941[77] | 902,312 |

| 1941[80] | 1,400,000 |

| 1941[77][81] | 456,639 |

| 1943[82] | 170,000 |

| 1959[76] | 930,000 |

| 1962[76] | 1,000,000 |

| 1976[76] | 1,384,000 |

| 1982[75] | 1,500,000 |

| 1989 | 1,593,970 |

| 1999 | 1,510,200 |

| 2001[83] | 1,470,900 |

| 2014[84] | 1,430,885 |

According to the 1989 Soviet Union Census, the population of the city was 1,593,970. In 1991, it decreased to 1,510,200, including 1,494,200 permanent residents.[85] Kharkiv is the second-largest city in Ukraine after the capital, Kiev.[86] The first independent all-Ukrainian population census was conducted in December 2001, and the next all-Ukrainian population census is decreed to be conducted in 2020. As of 2001, the population of the Kharkiv region is as follows: 78.5% living in urban areas, and 21.5% living in rural areas.[87]

Ethnicity

| Ethnic group | 1897[88] | 1926 | 1939 | 1959[89] | 1989[85] | 2001[90][91] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ukrainians | 25.9% | 38.6% | 48.5% | 48.4% | 50.4% | 62.8% |

| Russians | 63.2% | 37.2% | 32.9% | 40.4% | 43.6% | 33.2% |

| Jews | 5.7% | 19.5% | 15.6% | 8.7% | 3.0% | 0.7% |

Notes

- 1660 year – approximated estimation

- 1788 year – without the account of children

- 1920 year – times of the Russian Civil War

- 1941 year – estimation on May 1, right before German-Soviet War

- 1941 year – next estimation in September varies between 1,400,000 and 1,450,000

- 1941 year – another estimation in December during the occupation without the account of children

- 1943 year – August 23, liberation of the city; estimation varied 170,000 and 220,000

- 1976 year – estimation on June 1

- 1982 year – estimation in March

Religion

Kharkiv is an important religious center in Eastern Ukraine.

There are many old and new cathedrals, associated with various churches in Kharkiv.

The St. Assumption Orthodox Cathedral was built in Kharkiv in the 1680s and re-built in 1820s-1830s.[92]

The St. Pokrovsky Orthodox Monastery Cathedral was created in Kharkiv in 1689–1729.[93][94]

The St. Annunciation Orthodox Cathedral is one of the tallest Orthodox churches in the world. It was completed in Kharkiv on October 2, 1888.[95]

The St. Trinity Orthodox Cathedral was built in Kharkiv in 1758–1764 and re-built in 1857–1861.[96]

The St. Valentine Orthodox Cathedral was built in Kharkiv in the 2010s.[97]

The St. Tamara Orthodox Cathedral was built in Kharkiv in 2012.[98]

The St. Peace Bringing Wives Orthodox Cathedral was built in green park near Mirror Stream fountain in August, 2015.[99]

The Roman Catholic St. Mary Cathedral was built in Kharkiv in 1887–1892.

There is the old Kharkiv Choral Synagogue, which was fully renovated in Kharkiv in 1991–2016. The Jewish population is around 8000 people in Kharkiv.[100]

There are two mosques including the Kharkiv Cathedral Mosque and one Islamic center in Kharkiv.

Economy

The 2016–2020 economic development strategy: "Kharkiv Success Strategy", is created in Kharkiv.[101][102][103]

International Economic Forum

The International Economic Forum: Innovations. Investments. Kharkiv Innitiatives! is being conducted in Kharkiv every year.[104]

In 2015, the International Economic Forum: Innovations. Investments. Kharkiv Innitiatives! was attended by the diplomatic corps representatives from 17 world countries, working in Ukraine together with top-management of trans-national corporations and investment funds; plus Ukrainian People's Deputies; plus Ukrainian Central government officials, who determine the national economic development strategy; plus local government managers, who perform practical steps in implementing that strategy; plus managers of technical assistance to Ukraine; plus business and NGO's representatives; plus media people.[104][105][106][107][108]

The key topics of the plenary sessions and panel discussions of the International Economic Forum: Innovations. Investments. Kharkiv Innitiatives! are the implementation of Strategy for Sustainable Development “Ukraine – 2020”, the results achieved and plan of further actions to reform the local government and territorial organization of power in Ukraine, export promotion and attraction of investments in Ukraine, new opportunities for public-private partnerships, practical steps to create “electronic government”, issues of energy conservation and development of oil and gas industry in the Kharkiv Region, creating an effective system of production and processing of agricultural products, investment projects that will receive funding from the State Fund for Regional Development, development of international integration, preparation for privatization of state enterprises.[104][105][106][107][108]

International Industrial Exhibitions

The international industrial exhibitions are usually conducted at the Radmir Expohall exhibition center in Kharkiv.[109]

Industrial corporations

During the Soviet era, Kharkiv was the capital of industrial production in Ukraine and the third largest centre of industry and commerce in the USSR. After the collapse of the Soviet Union the largely defence-systems-oriented industrial production of the city decreased significantly. In the early 2000s, the industry started to recover and adapt to market economy needs. Now there are more than 380 industrial enterprises concentrated in the city, which have a total number of 150,000 employees. The enterprises form machine-building, electro-technology, instrument-making, and energy conglomerates.

State-owned industrial giants, such as Turboatom and Elektrotyazhmash[110] occupy 17% of the heavy power equipment construction (e.g., turbines) market worldwide. Multipurpose aircraft are produced by the Antonov aircraft manufacturing plant. The Malyshev factory produces not only armoured fighting vehicles, but also harvesters. Khartron[111] is the leading designer of space and commercial control systems in Ukraine and the former CIS.

IT industry

As of April 2018, there were 25,000 specialists in IT industry of the Kharkiv region, 76% of them were related to computer programming. Thus, Kharkiv accounts for 14% of all IT specialists in Ukraine and makes the second largest IT location in the country, right after the capital Kyiv.[112]

Also, the number of active IT companies in the region to be 445, five of them employing more than 601 people. Besides, there are 22 large companies with the workers’ number ranging from 201 to 600. More than half of IT-companies located in the Kharkiv region fall into “extra small” category with less than 20 persons engaged. The list is compiled with 43 medium (81-200 employers) and 105 small companies (21-80).

Due to the comparably narrow market for IT services in Ukraine, the majority of Kharkiv companies are export-oriented with more than 95% of total sales generated overseas in 2017. Overall, the estimated revenue of Kharkiv IT companies will more than double from $800 million in 2018 to $1.85 billion by 2025. The major markets are North America (65%) and Europe (25%).[113]

Finance industry

Kharkiv is also the headquarters of one of the largest Ukrainian banks, UkrSibbank, which has been part of the BNP Paribas group since December 2005.

Trade industry

There are many large modern shopping malls in Kharkiv.

There are a large number of markets:

- Barabashovo market is the largest market in Ukraine and one of the largest markets in Europe.

- Blagoveshinskiy market.

- Konniy "horse" market.

- Sumskoi market [114]

- Raiskiy book market.

Science and education

_V_N_KARAZIN_KHARKIV_NATIONAL_UNIVERSITY_MAIN_BUILDING_IN_CITY_OF_KHARKIV_STATE_OF_UKRAINE_PHOTOGRAPH_BY_VIKTOR_O_LEDENYOV_20160621.jpg)

_V_N_KARAZIN_KHARKIV_NATIONAL_UNIVERSITY_NORTHERN_BUILDING_IN_CITY_OF_KHARKIV_STATE_OF_UKRAINE_PHOTOGRAPH_BY_VIKTOR_O_LEDENYOV_20160621.jpg)

_MECHNIKOV_LANDAU_KUZNETS_MONUMENTS_AT_V_N_KARAZIN_KHARKIV_NATIONAL_UNIVERSITY_IN_CITY_OF_KHARKIV_STATE_OF_UKRAINE_PHOTOGRAPH_BY_VIKTOR_O_LEDENYOV_20160621.jpg)

Higher education

The Vasyl N. Karazin Kharkiv National University is the most prestigious reputable classic university, which was founded due to the efforts by Vasily Karazin in Kharkiv in 1804–1805.[115][116] On 29 January [O.S. 17 January] 1805, the Decree on the Opening of the Imperial University in Kharkiv came into force.

The Roentgen Institute opened in 1931. It was a specialist cancer treatment facility with 87 research workers, 20 professors, and specialist medical staff. The facilities included chemical, physiology, and bacteriology experimental treatment laboratories. It produced x-ray apparatus for the whole country.[32]

The city has 13 national universities and numerous professional, technical and private higher education institutions, offering its students a wide range of disciplines. Kharkiv National University (12,000 students), National Technical University "KhPI" (20,000 students), Kharkiv National University of Radioelectronics (12,000 students), Kharkiv National Aerospace University "KhAI", Kharkiv National University of Economics, Kharkiv National University of Pharmacy, Kharkiv National Medical University are the leading universities in Ukraine.

More than 17,000 faculty and research staff are employed in the institutions of higher education in Kharkiv.

Scientific research

The city has a high concentration of research institutions, which are independent or loosely connected with the universities. Among them are three national science centres: Kharkiv Institute of Physics and Technology, Institute of Meteorology, Institute for Experimental and Clinical Veterinary Medicine and 20 national research institutions of the National Academy of Science of Ukraine, such as the B Verkin Institute for Low Temperature Physics and Engineering, Institute for Problems of Cryobiology and Cryomedicine, State Scientific Institution "Institute for Single Crystals", Usikov Institute of Radiophysics and Electronics (IRE), Institute of Radio Astronomy (IRA), and others. A total number of 26,000 scientists are working in research and development.

A number of world-renowned scientific schools appeared in Kharkiv, such as the theoretical physics school and the mathematical school.

There is the Kharkiv Scientists House in the city, which was built by A. N. Beketov, architect in Kharkiv in 1900. All the scientists like to meet and discuss various scientific topics at the Kharkiv Scientists House in Kharkiv.[117]

Public libraries

In addition to the libraries affiliated with the various universities and research institutions, the Kharkiv State Scientific V. Korolenko-library is a major research library.

Secondary schools

Kharkiv has 212 (secondary education) schools, including 10 lyceums and 20 gymnasiums.

Education centers

There is the educational "Landau Center", which is named after Prof. L.D. Landau, Nobel laureate in Kharkiv.[118]

Culture

Kharkiv is one of the main cultural centres in Ukraine. It is home to 20 museums, over 10 theatres and a number of art galleries. Large music and cinema festivals are hosted in Kharkiv almost every year.

Theatres

The Kharkiv National Academic Opera and Ballet Theatre named after N. V. Lysenko is the biggest theatre in Kharkiv.[119][120]

Kharkiv Ukrainian Drama Theatre named after T. G. Shevchenko is popular among Ukrainian speaking people [121]

The Kharkiv Academic Russian Drama Theatre named after A.S. Pushkin was recently renovated, and it is quite popular among locals.[122]

The Kharkiv Theatre of the Young Spectator (now the Theatre for Children and Youth) is one of the oldest theatres for children.[123]

The Kharkiv Puppet Theatre (The Kharkiv State Academic Puppet Theatre named after VA Afanasyev) is the first puppet theatre in the territory of Kharkiv. It was created in 1935.

The Kharkiv Academic Theatre of Musical Comedy is a theatre founded on 1 November 1929 in Kharkiv.

Literature

In the 1930s Kharkiv was referred to as a Literary Klondike. It was the centre for the work of literary figures such as: Les Kurbas, Mykola Kulish, Mykola Khvylovy, Mykola Zerov, Valerian Pidmohylny, Pavlo Filipovych, Marko Voronny, Oleksa Slisarenko. Over 100 of these writers were repressed during the Stalinist purges of the 1930s. This tragic event in Ukrainian history is called the "Executed Renaissance" (Rozstrilene vidrodzhennia). Today, a literary museum located on Frunze Street marks their work and achievements.

Today, Kharkiv is often referred to as the "capital city" of Ukrainian science fiction and fantasy.[124][125] It is home to a number of popular writers, such as H. L. Oldie, Alexander Zorich, Andrey Dashkov, Yuri Nikitin and Andrey Valentinov; most of them write in Russian and are popular in both Russia and Ukraine. The annual science fiction convention "Star Bridge" (Звёздный мост) has been held in Kharkiv since 1999.[126]

Music

There is the Kharkiv Philharmonic Society in the city. The leading group active in the Philharmonic is the Academic Symphony Orchestra. It has 100 musicians of a high professional level, many of whom are prize-winners in international and national competitions.

There is the Organ Music Hall in the city.[127] The Organ Music Hall is situated at the Assumption Cathedral presently. The Rieger–Kloss organ was installed in the building of the Organ Music Hall back in 1986. The new Organ Music Hall will be opened at the extensively renovated building of Kharkiv Philharmonic Society in Kharkiv in November, 2016.

The Kharkiv Conservatory is in the city.

The Kharkiv National University of Arts named after I.P. Kotlyarevsky is situated in the city.[128]

Kharkiv sponsors the prestigious Hnat Khotkevych International Music Competition of Performers of Ukrainian Folk Instruments, which takes place every three years. Since 1997 four tri-annual competitions have taken place. The 2010 competition was cancelled by the Ukrainian Ministry of Culture two days before its opening.[129]

The music festival: "Kharkiv - City of Kind Hopes" is conducted in Kharkiv.[130]

Movies

From 1907 to 2008, at least 86 feature films were shot in the city's territory and its region. The most famous is Fragment of an Empire (1929). Arriving in Leningrad, the main character, in addition to the usual pre-revolutionary buildings, sees the Gosprom - a symbol of a new era.

Movies festival

The Kharkiv Lilacs international movie festival is very popular among movie stars, makers and producers in Ukraine, Eastern Europe, Western Europe and North America.[131][132]

The annual festival is usually conducted in May.[131][131][132]

There is a special alley with metal hand prints by popular movies actors at Shevchenko park in Kharkiv. [132][133]

Visual arts

Kharkiv has been a home for many famous painters, including Ilya Repin, Zinaida Serebryakova, Henryk Siemiradzki, and Vasyl Yermilov. There are many modern arts galleries in the city: the Yermilov Centre, Lilacs Gallery, the Kharkiv Art Museum, the Kharkiv Municipal Gallery, the AC Gallery, Palladium Gallery, the Semiradsky Gallery, AVEK Gallery, and Arts of Slobozhanshyna Gallery among others.

Museums

_-_Ukraine_(30095280368).jpg)

There is the M. F. Sumtsov Kharkiv Historical Museum in the city.[134]

The Natural History Museum at V. N. Karazin Kharkiv National University was founded in Kharkiv on April 2, 1807. The museum is visited by 40000 visitors every year.[135][136]

The V. N. Karazin Kharkiv National University History Museum was established in Kharkiv in 1972.[137][138][139]

The V. N. Karazin Kharkiv National University Archeology Museum was founded in Kharkiv on March 20, 1998. [140][141]

The National Technical University "Kharkiv Polytechnical Institute" Museum was created in Kharkiv on December 29, 1972.[142][143][144][145][146]

The National Aerospace University "Kharkiv Aviation Institute" Museum was founded on May 29, 1992.[147]

The "National University of Pharmacy" Museum was founded in Kharkiv on September 15, 2010.[148][149][150]

There are around 147 museums in the Kharkiv's region.[151]

The Kharkiv Maritime Museum - a museum dedicated to the history of shipbuilding and navigation.[152]

The Kharkiv Puppet Museum is the oldest museum of dolls in Ukraine.

Memorial museum-apartment of the family Grizodubov.

Club-Museum of Claudia Shulzhenko.[153]

The Museum of "First Aid".

The Museum of Urban Transport.

Landmarks

Of the many attractions of the Kharkiv city are the: Dormition Cathedral, Annunciation Cathedral, Derzhprom building, Freedom Square, Taras Shevchenko Monument, Mirror Stream, Historical Museum, Choral Synagogue, T. Shevchenko Gardens, Zoo, Children's narrow-gauge railroad, World War I Tank Mk V, Memorial Complex, and many more.

After the 2014 Russian annexation of Crimea the monument to Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny in Sevastopol was removed and handed over to Kharkiv.[154]

Media

There are a large number of broadcast and internet TV channels, AM/FM/PM/internet radio-stations, and paper/internet newspapers in Kharkiv. Some are listed below.

Newspapers

- Vremya

- Vecherniy Kharkiv

- Segodnya

- Vesti

- Khar'kovskie Izvestiya

Magazines

- Guberniya [155]

TV stations

- "7 канал" channel

- "А/ТВК" channel

- "Simon" channel

- "ATN Kharkov" channel

- "UA: Харків" channel

Radio stations

- Promin'

- Ukrains'ke Radio

- Radio Kharkiv

- Kharkiv Oblastne Radio

- Russkoe Radio Ukraina

- Shanson

- Retro FM

Online news in English

- The Kharkiv Times

- Kharkiv Observer

Transport

The city of Kharkiv is one of the largest transportation centers in Ukraine, which is connected to numerous cities of the world by air, rail and road traffic. The city has many transportation methods, including: public transport, taxis, railways, and air traffic. There are about 250 thousand cars in the city.[156]

Local transport

Being an important transportation centre of Ukraine, many different means of transportation are available in Kharkiv. Kharkiv's Metro is the city's rapid transit system operating since 1975. It includes three different lines with 30 stations in total.[157][158] The Kharkiv buses carry about 12 million passengers annually. Trolleybuses, trams (which celebrated its 100 years of service in 2006), and marshrutkas (private minibuses) are also important means of transportation in the city.

Railways

The first railway connection of Kharkiv was opened in 1869. The first train to arrive in Kharkiv came from the north on 22 May 1869, and on 6 June 1869, traffic was opened on the Kursk–Kharkiv–Azov line. Kharkiv's passenger railway station was reconstructed and expanded in 1901, to be later destroyed in the Second World War. A new Kharkiv railway station was built in 1952.[159]

Kharkiv is connected with all main cities in Ukraine and abroad by regular railway trains. Regional trains known as elektrichkas connect Kharkiv with nearby towns and villages.

Air

Kharkiv is served by Kharkiv International Airport has been granted international status. Charter flights are also available. The former largest carrier of the Kharkiv Airport — Aeromost-Kharkiv — is not serving any regular destinations as of 2007. The Kharkiv North Airport is a factory airfield and was a major production facility for Antonov aircraft company.

Recreation

Kharkiv contains numerous parks and gardens such as the Gor'ky park, Shevchenko park, Hydro park, Strelka park, Sarzhyn Yar and Feldman ecopark. The Gor'ky park is a common place for recreation activities among visitors and local people. The Shevchenko park is situated in close proximity to the V.N. Karazin National University. It is also a common place for recreation activities among the students, professors, locals and foreigners. The Ecopark is situated at circle highway around Kharkiv. It attracts kids, parents, students, professors, locals and foreigners to undertake recreation activities. Sarzhyn Yar is a natural ravine three minutes walk from “Botanichniy Sad” station. It is an old girder that now - is a modern park zone more than 12 km length. There is also a mineral water source with cupel and a sporting court.[160]

Sport

Kharkiv International Marathon

The Kharkiv International Marathon is considered as a prime international sportive event, attracting many thousands of professional sportsmen, young people, students, professors, locals and tourists to travel to Kharkiv and to participate in the international event.[161][162][163][164]

Football (soccer)

The most popular sport is football. The city has several football clubs playing in the Ukrainian national competitions. The most successful is FC Dynamo Kharkiv that won eight national titles back in 1920s–1930s.

- FC Metalist Kharkiv, a defunct club, which played at the Metalist Stadium

- FC Metalist 1925 Kharkiv, which plays at the Metalist Stadium

- FC Helios Kharkiv, a defunct club, which played at the Helios Arena

- FC Kharkiv, a defunct club, which played at the Dynamo Stadium

- FC Arsenal Kharkiv, which played at the Arsenal-Spartak Stadium (participates in regional competitions)

- FC Shakhtar Donetsk also play at the Metalist Stadium since 2017, due to the war in Donbass

There is also a female football club WFC Zhytlobud-1 Kharkiv, which represented Ukraine in the European competitions and constantly is the main contender for the national title.

Metalist Stadium hosted three group matches at UEFA Euro 2012.

Other sports

_BYCICLE_COMPETITION_AT_BYCICLE_DAY_IN_CITY_OF_KHARKIV_STATE_OF_UKRAINE_PHOTOGRAPH_BY_VIKTOR_O_LEDENYOV_20160709.jpg)

Kharkiv also had some ice hockey clubs, MHC Dynamo Kharkiv, Vityaz Kharkiv, Yunost Kharkiv, HC Kharkiv, who competed in the Ukrainian Hockey Championship.

Avangard Budy is a bandy club from Kharkiv, which won the Ukrainian championship in 2013.

There are a men's volleyball teams, Lokomotyv Kharkiv and Yurydychna Akademіya Kharkiv, which performed in Ukraine and in European competitions.

RC Olymp is the city's rugby union club. They provide many players for the national team.

Tennis is also a popular sport in Kharkiv. There are many professional tennis courts in the city. Elina Svitolina is a tennis player from Kharkiv.

There is a golf club in Kharkiv.[165]

Horseriding as a sport is also popular among locals.[166][167][168][169] There are large stables and horse riding facilities at Feldman Ecopark in Kharkiv.[170]

There is a growing interest in cycling among locals.[171][172] There is a large bicycles producer, Kharkiv Bicycle Plant within the city.[173] Presently, the modern bicycle highway is under construction at the "Leso park" district in Kharkiv.

Notable people

- Zina Andri — Founder of Albanian National Theater and stage director, born Zinaida Andrejenko in Kharkiv, Ukraine.

- Nikolai P. Barabashov — astronomer, co-author of the first pictures of the far side of the moon

- Pavel Batitsky — Soviet military leader

- Vladimir Bobri — illustrator, author, composer, educator and guitar historian

- Inna Bohoslovska — lawyer, politician and leader of the Ukrainian public organization Viche

- Sergei Bortkiewicz — Russian Romantic composer and pianist

- Maria Burmaka – Ukrainian singer, musician and songwriter

- Leonid Buryak - football coach and former footballer

- Leonid Bykov – Soviet actor, film director, and script writer

- Adolphe Mouron Cassandre — Ukrainian-French painter, commercial poster artist, and typeface designer

- Valentina Chepiga – female bodybuilder and 2000 Ms. Olympia champion

- Juliya Chernetsky (Mistress Juliya) — television host, actress, model, and music promoter in the United States

- Olga Danilov — Israeli Olympic speed skater

- Alexander Davidovich — Israeli Olympic wrestler

- Andrey Denisov — Russian diplomat

- Vladimir Drinfeld — mathematician, awarded Fields Medal in 1990

- Isaak Dunayevsky — Soviet composer and conductor

- Konstanty Gorski — Polish composer, violist, organist and music teacher

- Valentina Grizodubova — one of the first female pilots in the Soviet Union

- Lyudmila Gurchenko (Hurchenko) – Soviet and Russian actress, singer and entertainer

- Mikhail Gurevich — (originally from Rubanshchina) Soviet aircraft designer, a partner (with Artem Mikoyan) of the MiG military aviation bureau

- Mikhail Gurevich — Ukrainian chess player

- Oleksandr Gvozdyk — boxer

- Diana Harkusha — Miss Ukraine Universe 2014 and Miss Universe 2014's 2nd Runner-up

- Leonid Haydamaka — bandurist, conductor, founder of first orchestra of Ukrainian folk instruments

- Pavlo Ishchenko (born 1992), Olympic Ukrainian-Israeli boxer

- Maksym Kalynychenko – footballer

- Vasily Karazin — founder of Kharkiv University, which now bears his name

- Hnat Khotkevych — writer, ethnographer, composer, bandurist

- Mikhail Koshkin — (originally from Brynchagi), chief designer of Soviet tank T-34

- Olga Krasko — Russian actress

- Mykola Kulish — playwright

- Les Kurbas — dramatist

- Simon Kuznets — Russian American economist

- Evgeny Lifshitz — Soviet physicist

- Eduard Limonov — writer, poet and controversial politician

- Gleb Lozino-Lozinskiy — lead developer of Soviet Shuttle Buran program

- Aleksandr Lyapunov — Russian mathematician, mechanician and physicist, inventor of motion stability theory

- Boris Mikhailov — photographer and artist

- Mykola Mikhnovsky — Ukrainian political leader and activist

- T-DJ Milana (born 1989), DJ, composer, dancer and model, lives in Kharkiv

- Yuri Nikitin — writer

- Henry Lion Oldie (Dmitry Gromov and Oleg Ladyzhensky) — writers

- Igor Olshanetskyi — Israeli Olympic weightlifter

- Justine Pasek — Miss Universe 2002

- Valerian Pidmohylny — poet

- Irina Press — athlete who won two Olympic gold medals

- Tamara Press — Soviet shot putter and discus thrower

- Olga Rapay-Markish — ceramicist

- Igor Rybak — Olympic champion lightweight weightlifter

- Serafina Schachova – nephrologist

- Eugen Schauman – Finnish nationalist who killed Russian general N. A. Bobrikov in 1904

- Alexander Shchetynsky — composer

- George Shevelov – Ukrainian and Slavic linguist, philologist, essayist, literary historian, and literary critic

- Elena Sheynina — children's author

- Lev Shubnikov — Soviet experimental physicist who worked in the Netherlands and USSR

- Klavdiya Shulzhenko — singer of the Soviet Union

- Alexander Siloti — Russian pianist, conductor and composer

- Hryhorii Skovoroda – poet, philosopher and composer

- Karina Smirnoff – world champion dancer, starring on Dancing with the Stars

- Jura Soyfer — Austrian political journalist and cabaret writer

- Otto Struve — Russian-American astronomer

- Sergei Sviatchenko – artist

- Elina Svitolina - tennis player

- Mark Taimanov — chess player and concert pianist

- Ievgeniia Tetelbaum — Israeli Olympic synchronized swimmer

- Nikolai Tikhonov — Premier of the Soviet Union

- Yevgeniy Timoshenko — poker player

- Artem Tsoglin (born 1997) - Israeli pair skater

- Anna Tsybuleva — pianist, winner of the Leeds International Piano Competition

- Anna Ushenina — women's world chess champion

- Vladimir Vasyutin — Soviet cosmonaut of Ukrainian descent

- Yury Vengerovsky — Olympic gold medal winning volleyball player

- Vitali Vitaliev - journalist and author

- Alexander Voevodin — biomedical scientist and educator

- Igor Vovchanchyn – Mixed martial artist

- Vasyl Yermylov – painter and designer

- Serhiy Zhadan — poet, novelist, and translator

- Oleksandr Zhdanov - Ukrainian-Israeli footballer

- Irina Zhurina – opera singer, People's Artist of Russia

- Alexander Zorich (Dmitry Gordevsky and Yana Botsman), writers

Nobel and Fields prize winners

- Lev Landau – (originally from Baku) a head of the department of theoretical physics at the Kharkiv Institute of Physics and Technology, a head of the department of experimental physics and a lecturer at the department of theoretical physics at the Kharkiv State University, a head of the department of theoretical physics at the Kharkiv Polytechnic Institute 1932–37, Nobel Prize for Physics 1962

- Simon Kuznets (economics)

- Ilya Mechnikov (medicine)

- Vladimir Drinfeld (mathematics)

Twin towns – sister cities

Footnotes

- Kharkiv was a capital of the Soviet Ukraine for some 15 years in 1919–1934.

References

- Первая столица. АТН, 19 декабря 2002 г. (in Russian)

- What Makes Kharkiv Ukrainian, The Ukrainian Week (23 November 2014)

- (in Ukrainian) Another 48 streets and 5 districts "decommunized" in Kharkiv, Ukrayinska Pravda (3 February 2015)

(in Russian) Three districts renamed in Kharkiv, SQ (3 February 2015)

(in Ukrainian) It was decided not to rename the Zhovtnevyi and the Frunzenskyi districts in Kharkiv, Korrespondent.net (3 February 2015) -

Kernes wins elections for Kharkiv mayor with over 65% of vote, Interfax-Ukraine (31 October 2015)

FC Metalist President Kurchenko to invest in Kharkiv’s preparations for EuroBasket 2015, Interfax-Ukraine (8 April 2013) - Ukraine's second Winter Olympics: one medal, some good performances, The Ukrainian Weekly (1 March 1998)

- "Kharkiv on Encyclopædia Britannica - current edition". Britannica.com. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- Kharkiv "never had eastern-western conflicts", Euronews (23 October 2014)

- Liber, George (1992). Soviet Nationality Policy, Urban Growth, and Identity Change in the Ukrainian SSR, 1923-1934. Cambridge University Press.

- "Сторінка:Котляревський. Енеида на малороссійскій языкъ перелицїованная. 1798.pdf/175 — Вікіджерела". uk.wikisource.org. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- Grigory Savvich Skovoroda, Full collection of works, (Garden of Divine Songs), v. 2, in Teaching Thought, Kiev 1973.

- Roman Solchanyk (January 2001). Ukraine and Russia: The Post-Soviet Transition. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-7425-1018-0. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- (in Ukrainian) Живий Харків. Нічна екскурсія містом-господарем (Living Kharkiv. Nightly excursion through the host-city) Ukrayinska Pravda. June 9, 2012

- Ukraine: A History 4th Edition by Orest Subtelny, University of Toronto Press, 2009, ISBN 1442609915

- Указ об учреждении губерний и о росписании к ним городов, 1708 г., декабря 18 [Decree on the establishment of Provinces and cities assigned to them, December 18, 1708]. constitution.garant.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- История административно-территориального деления воронежского края. 2. Воронежская губерния [History of the Administrative-Territorial Division of the Voronezh Region. 2. Voronezh Province.] (in Russian). Archive service of Voronezh Oblast. Archived from the original on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- У Харкові відкрили меморіальну дошку Івану Франку [A memorial plaque to Ivan Franko was unveiled in Kharkiv] (in Ukrainian). Istpravda.com.ua. 23 August 2011. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- Харків і харків'яни XIX-го сторіччя [Kharkiv and Kharkiv denizens in 19th century photos] (in Ukrainian). Istpravda.com.ua. 24 January 2011. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- "Hromadas". Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- Балтин, А. "Харьковская организация Р. С.-Д. Р. П. большевиков во время войны." // Летопись Революции. - 1923. No.5. С. 3-20

- Historical Dictionary of Ukraine (Historical Dictionaries of Europe) by Ivan Katchanovski, Scarecrow Press (Publication date: July 11, 2013), ISBN 0810878453 (page 713)

- Literary Politics in the Soviet Ukraine, 1917–1934. Durham and London: Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-1099-6 (page 7)

- World War I: A Student Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 1195. ISBN 978-1-85109-879-8

- Ukraine: The Phony War?, The New York Review of Books (27 April 2014)

- Spies and Commissars: The Early Years of the Russian Revolution. PublicAffairs. ISBN 1-61039-140-3.

- Borderlands into Bordered Lands: Geopolitics of Identity in Post-Soviet Ukraine (Soviet and Post-Soviet Politics and Society, Vol. 98) (Volume 98), Ibidem Verlag, 2010, ISBN 383820042X (page 24)

- The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression, Harvard University Press, 858 pages, ISBN 0-674-07608-7, page 97

- The A to Z of the Russo-Japanese War. Scarecrow Press Inc. ISBN 978-0-8108-6841-0 (page 101)

- "Донбас і Україна (з історії революційної боротьби 1917–18 рр.) (Donbas and Ukraine. (From articles and declarations of Mykola Skrypnyk))". Istpravda.com.ua. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- Games from the Past: The continuity and change of the identity dynamic in Donbas from a historical perspective , Södertörn University (May 19, 2014)

- Language Policy in the Soviet Union by Lenore Grenoble, Springer Science+Business Media, 2003, ISBN 978-1-4020-1298-3 (page 84)

- "Derzhprom statistics". Kharkov.ua. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- Khwaja, Barbara (26 May 2017). "Health Reform in Revolutionary Russia". Socialist Health Association. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- "Picture of the building in the Vsesvit magazine". Istpravda.com.ua. 2012-04-30. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- "Photos of the newspaper "Proletarian" for 1932-33". Istpravda.com.ua. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- Ukrainian minstrels: and the blind shall sing by Natalie Kononenko, M.E. Sharp, ISBN 0-7656-0144-3/ISBN 978-0-7656-0144-5, page 116

- Fischer, Benjamin B., "The Katyn Controversy: Stalin's Killing Field", Studies in Intelligence, Winter 1999–2000, last accessed on 10 December 2005

- "Харків часів "дорослого дитинства" Людмили Гурченко (Kharkiv at times of "matured childhood" of Lyudmila Gurchenko)". Istpravda.com.ua. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- "Kharkiv through the eyes of Lyudmila Gurchenko". Andersval.nl. 2011-03-31. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- The Red Army committed 765,300 men to this offensive, suffering 277,190 casualties (170,958 killed/missing/PoW, 106,232 wounded) and losing 652 tanks, and 4,924 guns and mortars. Glantz, David M., Kharkov 1942, anatomy of a military disaster through Soviet eyes, pub Ian Allan, 1998, ISBN 0-7110-2562-2 page 218.

- per Robert M. Citino, author of "Death of the Wehrmacht", and other sources, the Red Army came to within a few miles of Kharkiv on 14 May 1942 by Soviet forces under Marshal Timoshenko before being driven back by German forces under Field Marshal Fedor von Bock, p. 100

- Karpyuk, Gennady (23–29 December 2006), "Трагедія, про яку дехто не дуже хотів знати" [A tragedy that not everyone wanted to know about], Дзеркало Тижня (No. 49 (628)), archived from the original on 9 December 2008, retrieved 16 December 2011CS1 maint: date format (link)

- "Про зміну і встановлення меж міста Харків, Дергачівського і Харківського районів Харківської області". Search.ligazakon.ua. 2012-09-18. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- In↑ «Сегодня»,21 December 2007.

- "Weather and Climate - The Climate of Kharkiv" (in Russian). Weather and Climate (Погода и климат). Archived from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- "Har'Kov (Kharkiv) Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- "Ukraine crisis: Timeline". BBC News. 13 November 2014. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- Roth, Andrew (4 March 2014). "From Russia, 'Tourists' Stir the Protests". The New York Times.

"Russian site recruits 'volunteers' for Ukraine". BBC News. 4 March 2014. - "Pro-Russia activists declare establishment of 'Kharkiv people's republic'". Focus Information Agency. 7 April 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- "Kharkiv settles down, while pro-Russian separatists still hold buildings in Luhansk, Donetsk". Kyiv Post. 8 April 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- "Protesters Storm Kharkiv Theater Thinking It Was City Hall". The Moscow Times. 8 April 2014.

- "Kharkiv city government building infiltrated by pro-Russian protesters". Kyiv Post. 13 April 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- "Кернес пообіцяв допомогти звільнити затриманих сепаратистів | Українська правда". Pravda.com.ua. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- Kharkiv torn between Europe and Russia, Deutsche Welle (6 March 2014)

- "После нападения антимайдановцев на митинг Евромайдана в Харькове пострадало 50 человек : Новости УНИАН". Unian.net. 14 April 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- "Latest from the Special Monitoring Mission in Ukraine". Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe. 14 April 2014. Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- "Latest from the Special Monitoring Mission in Ukraine – based on information received up until 29 April 2014" (Press release). Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. 30 April 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- "Latest from the Special Monitoring Mission in Ukraine based on information received until 23 June 2014" (Press release). Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. 24 June 2014. Archived from the original on 22 November 2015. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

- "Latest from the Special Monitoring Mission (SMM) in Ukraine based on information received until 18:00 hrs, 23 July" (Press release). Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. 24 July 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- (in Ukrainian) Two liberty square rally, Status quo (17 August 2014)

- Ukrainian Crowds Topple Lenin Statue (Again). Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- Лише 3% українців хочуть приєднання їх області до Росії [Only 3% of Ukrainians want their region to become part of Russia]. Dzerkalo Tyzhnia (in Ukrainian). 3 January 2015.

- Seven recent blasts in Ukraine city stir fear of new Russian menace, Los Angeles Times (11 December 2014)

Mysterious spate of bombings hit Ukraine military hub, Agence France-Presse (10 December 2014) - SBU: Russian special services target Kharkiv, Odesa, situation difficult to control, Ukrainian Independent Information Agency (10 December 2014)

- Міліція з ясовує, хто напав на волонтерську "Станцію Харків" [Police finds out who attacked the volunteer-run "Station Kharkiv"] (in Ukrainian). ukrinform.ua. 9 January 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2015."Станция Харьков" — первый пункт помощи переселенцам из зоны АТО ["Station Kharkiv" - the first point of assistance for displaced persons from the Donbass zone] (in Russian). 24tv.ua. 25 October 2014. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- UNIAN Anti-terrorist operation launched in Kharkiv due to fatal blast on Sunday – Turchynov, 22 February 2015.

En.Censor.Net, Anti-terrorist operation started in Kharkiv: four participants on the explosion detained, 22 February 2015.

Novorossia.Today, Turchinov announced start of the ATO in Kharkov. The highest level of terrorist threat had been introduced in the city, 23 February 2015. - Lada Ray (23 February 2015). "Urgent Statement of the Kharkov Partizans re. False Flag Terrorist Act". Futurist Trendcast. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- Bomb Attacks Increase In Ukraine's Second-Largest City, Kharkiv, NPR (6 April 2015)

Kharkiv explosion targeting Ukrainian flag classified as ‘terrorist act', Ukraine Today (7 April 2015)

Explosion In Ukraine's Kharkiv Targets National Flag Memorial, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (7 April 2015) - Unian, Over 200 men in balaclavas brawl at Kharkiv town hall, clash with police, 23 September 2015, 14:10.

- Korrespondent, Появилось видео столкновений у горсовета Харькова [Video of riot at Kharkov City Council], 23 September 2015 17:40

- (in Russian) List of 170 renamed streets, SQ (20 November 2015)

(in Ukrainian) Kharkiv city council renamed 173 streets, 4 parks and a metro station, RBC Ukraine (20 November 2015)

(in Russian) 50 streets renamed in Kharkiv: list, SQ (3 February 2015) - (in Ukrainian) In Kharkiv, five metro stations and fifty streets have been communicated, Korrespondent.net, 18 May 2016)

- (in Russian) Districts Of Kharkiv. History with geography, SQ (23 February 2015)

- Л.И. Мачулин. Mysteries of the underground Kharkov. — Х.: 2005. ISBN 966-8768-00-0 (in Russian)

- Kharkov: Architecture, monuments, renovations: Travel guide. Ed. А. Лейбфрейд, В. Реусов, А. Тиц. — Х.: Прапор, 1987(in Russian)

- N. T. Dyachenko (1977). Улицы и площади Харькова [Streets and squares of Kharkov]. dalizovut.narod.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- А.В. Скоробогатов. Kharkov in times of German occupation (1941–1943). – X.: Прапор, 2006. ISBN 966-7880-79-6(in Ukrainian)

- Oleksandr Leibfreid, Yu. Poliakova. Kharkov. From fortress to capital. – Х.: Фолио, 2004(in Russian)

- State archives of Kharkov Oblast. Ф. Р-2982, оп. 2, file 16, pp 53–54

- Colonel Н. И. Рудницкий. Военкоматы Харькова в предвоенные и военные годы.(in Russian)

- In reference to the German census of December 1941; without children and teenagers no older 16 years of age; numerous city-dwellers evaded the registration(in Russian)

- Nikita Khrushchev. Report to ЦК ВКП(б) of August 30, 1943. History: without «white spots». Kharkiv izvestia, No. 100–101, August 23, 2008, page 6(in Russian)

- Ukrainian Census (2001)

- "Major Cities in Ukraine by Population (2014)". World Population Review. Retrieved 2014-04-14.

- "Kharkiv today". Our Kharkiv (in Russian). Archived from the original on 22 August 2006. Retrieved 4 May 2007.

- "Results / General results of the census / Number of cities". 2001 Ukrainian Census. Archived from the original on 9 January 2006. Retrieved 28 August 2006.

- "Всеукраїнський перепис населення 2001 | English version | Results | General results of the census | Urban and rural population:". 2001.ukrcensus.gov.ua. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- Первая всеобщая перепись населения Российской Империи 1897 г. Распределение населения по родному языку и уездам 50 губерний Европейской России Демоскоп

- Історія міста Харкова ХХ століття, Харків 2004, р. 456

- "Общая информация о Харькове на vharkov". vharkov.ru. Archived from the original on 29 August 2014. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "Всеукраїнський перепис населення 2001 – Результати – Основні підсумки – Загальна кількість населення – Харківська область:". 2001.ukrcensus.gov.ua. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "Харьковская епархия Украинской Православной Церкви". eparchia.kharkov.ua. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "Харьковская епархия Украинской Православной Церкви". eparchia.kharkov.ua. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "Официальный сайт Свято-Покровского мужского монастыря г. Харьков". pokrovsky-monastyr.kh.ua. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "Харьковская епархия Украинской Православной Церкви". eparchia.kharkov.ua. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "Харьковская епархия Украинской Православной Церкви". eparchia.kharkov.ua. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "Харьковская епархия Украинской Православной Церкви". eparchia.kharkov.ua. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "Освящен храм благоверной царицы Тамары города Харькова – Харьковская епархия". eparchia.kharkov.ua. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "Харьковская епархия Украинской Православной Церкви". eparchia.kharkov.ua. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "Kharkov Jewish Community". jewishkharkov.org. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "Розробка стратегії розвитку міста Харкова на 2016-2020 роки «Харків – стратегія успіху»". strategy.kharkov.ua. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "Круглий стіл «Розробка Стратегії розвитку міста Харкова до 2020 року: наука і освіта» >> ХНУ імені В. Н. Каразіна". univer.kharkov.ua. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- Hulu LLC. "В університеті Каразіна обговорять перспективи розвитку освіти". city.kharkov.ua. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "www.led.org.ua/en/". led.org.ua. Archived from the original on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "VII International economic forum "INNOVATIONS. INVESTMENTS. KHARKIV INITIATIVES!" - Announcements - Embassy of Ukraine in the United States of America". usa.mfa.gov.ua. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "www.kmu.gov.ua/control/publish/article?art_id=247530844". kmu.gov.ua. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "statements/amb-kharkiv-econ-forum-09042015". ukraine.usembassy.gov. Archived from the original on 7 January 2017. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "Kharkiv – U.S. Embassy Kyiv Blog". usembassykyiv.wordpress.com. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "Radmir Expohall | Radmir Expohall". radmir-expohall.com.ua. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "spetm.com.ua". spetm.com.ua. Archived from the original on 28 September 2008. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- "Hartron: Forms of cooperation". hartron.com.ua. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- "Kharkiv". Kharkiv. Retrieved 2019-06-13.

- "Kharkiv". Kharkiv. Retrieved 2019-06-13.

- "Торговый центр "Сумской рынок" по адресу Харьков, Шевченковский район, Культуры, 8". kharkov.info. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "Харківський національний університет імені В. Н. Каразіна". univer.kharkov.ua. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "Харківський національний університет імені В.Н. Каразіна". vnz.univ.kiev.ua. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "house". khdu.org. Archived from the original on 27 July 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "ПРО "ЛАНДАУЦЕНТР" |". landaucentre.org. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "Головна - ХАТОБ, ХНАТОБ, хатоб харьков, хатоб афиша, хатоб 2017, афиша хатоб 2017, хатоб сайт, хатоб харьков официальный, хатоб официальный сайт, хатоб харьков сайт, хатоб харьков официальный сайт, хатоб харьков афиша, хнатоб сайт, хнатоб официальный, хнатоб официальный сайт, афиша хнатоб, хнатоб сайт афиша, хнатоб билеты, хнатоб харьков, хнатоб купить билеты, хнатоб официальный сайт афиша, хнатоб афиша". hatob.com.ua. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "Home". hatob.com.ua. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "Харківський Державний Академічний Драматичний Театр ім. Т.Г.Шевченка". theatre-shevchenko.com.ua. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "rusdrama.kh.ua/". rusdrama.kh.ua. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "Харьковский театр для детей и юношества" [Theatre for Children and Youth]. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- "Kharkiv city guide". uefa.com. 25 January 2010. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- "Ukraine Travel Guide: Kharkiv, Ukraine". ukrainetravel.co. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- "Kharkiv International Festival of Science Fiction "Star Bridge - 2011"". V. N. Karazin Kharkiv National University. September 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- "Органный зал, Харьков – концерты, камерная и органная музыка | Харьковская филармония". filarmonia.kh.ua. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "Харківський національний університет мистецтв ім І.П.Котляревського". dum.kharkov.ua. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "Минкультуры запретил Харькову проводить конкурс им. Гната Хоткевича - Комментарии". Proua.com. 2010-04-16. Archived from the original on 28 December 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- "Фестиваль "Харків - місто добрих надій". Информация для участников | Харьковская филармония". filarmonia.kh.ua. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "Харьковская сирень - Главная". sirenfest.net.ua. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "times.kh.ua/news/fresh/kharkovskaya_siren_2016_novye_ladoni_znamenitykh_akterov_na_allee_zvezd_foto/158954/". times.kh.ua. Archived from the original on 24 October 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "Возвращение "Харьковской сирени": новые ладони знаменитых актеров на Аллее звезд (ФОТО) | Восточный Дозор". kharkov.dozor.ua. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "Information in English - Харківський історичний музей імені М.Ф.Сумцова". museum.kh.ua. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- "Музей природы >> ХНУ имени В. Н. Каразина". univer.kharkov.ua. Retrieved 18 June 2017.