Ilya Repin

Ilya Yefimovich Repin (Russian: Илья Ефимович Репин, tr. Il'ya Yefimovich Repin, IPA: [ˈrʲepʲɪn]; Finnish: Ilja Jefimovitš Repin; Ukrainian: Ілля Юхимович Рєпін; 5 August [O.S. 24 July] 1844 – 29 September 1930) was a Russian[1][2] realist painter. He was the most renowned Russian artist of the 19th century, when his position in the world of art was comparable to that of Leo Tolstoy in literature. He played a major role in bringing Russian art into the mainstream of European culture. His major works include Barge Haulers on the Volga (1873), Religious Procession in Kursk Province (1883) and Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks (1880–1891).

Ilya Repin | |

|---|---|

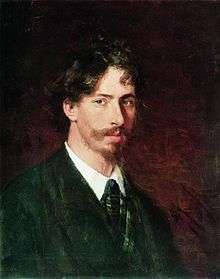

Self-portrait, 1878 (State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg). | |

| Born | Ilya Yefimovich Repin 5 August [O.S. 24 July] 1844 |

| Died | 29 September 1930 (aged 86) |

| Nationality | Russian Empire (1844–1918) Finland (1918–1930) |

| Education | Full Member Academy of Arts (1893) |

| Alma mater | Imperial Academy of Arts |

| Known for | Painting |

Notable work | Barge Haulers on the Volga (1870–1873) Religious Procession in Kursk Province (1880–1883) Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks (1880–1891) |

| Movement | Realism |

| Awards | Legion of Honour (1901) |

| Patron(s) | Pavel Tretyakov |

Repin was born in Chuguyev, in Kharkov Governorate, Russian Empire (now Chuhuiv in Ukraine, Kharkiv Region) into a family of "military settlers".[3] His father traded horses and his grandmother ran an inn. He entered military school to study surveying. Soon after the surveying course was cancelled, his father helped Repin to become an apprentice with Ivan Bunakov, a local icon painter, where he restored old icons and painted portraits of local notables through commissions. In 1863 he went to St. Petersburg Art Academy to study painting but had to enter Ivan Kramskoi preparatory school first. He met fellow artist Ivan Kramskoi and the critic Vladimir Stasov during the 1860s, and his wife, Vera Shevtsova in 1872 (they remained married for ten years). In 1874–1876 he showed at the Salon in Paris and at the exhibitions of the Itinerants' Society in Saint Petersburg. He was awarded the title of academician in 1876.

In 1880 Repin travelled to Zaporizhia to gather material for the 1891 Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks. His Religious Procession in Kursk Province was exhibited in 1883, and Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan in 1885. In 1892 he published the Letters on Art collection of essays. He taught at the Higher Art School attached to the Academy of Arts from 1894. In 1898 he purchased an estate, Penaty (the Penates), in Kuokkala, Finland (now Repino, Saint Petersburg).

In 1901 he was awarded the Legion of Honour. In 1911 he traveled with his common-law wife Natalia Nordman to the World Exhibition in Italy, where his painting 17 October 1905 and his portraits were displayed in their own separate room. In 1916 Repin worked on his book of reminiscences, Far and Near, with the assistance of Korney Chukovsky. He welcomed the February Revolution of 1917, but was rather skeptical towards the October Revolution. Soviet authorities asked him a number of times to come back, he remained in Finland for the rest of his life. Celebrations were held in 1924 in Kuokkala to mark Repin's 80th birthday, followed by an exhibition of his works in Moscow. In 1925 a jubilee exhibition of his works was held in the Russian Museum in Leningrad. Repin died in 1930 and was buried at the Penates.

Biography

Early life

Repin was born in the town of Chuguyev, in the Kharkov Governorate of the Russian Empire, in the heart of the historical region of the Sloboda Ukraine.[4] His father Yefim Vasilyevich Repin (1804—1894) was a private in the Uhlan Regiment of the Imperial Russian Army who fought during the Russo-Persian War (1826–1828), the Russo-Turkish War (1828–29) and the Hungarian campaign (1849) while making money on horse trade, his mother Tatiana Stepanovna Repina (née Bocharova) (1811—1880), also a daughter of a former private of the local Cossack Regiment, had family ties to noblemen and officers; the Repins had six children and were quite wealthy.[5][6] As a boy Ilya was educated at the local school where his mother taught.[7] From 1854 he attended a military Cantonist school. He did not have fond recollections of his childhood, mainly due to the military settlements his family lived in.[3]

In 1856 he became a student of Ivan Bunakov, a local icon painter. In 1859–1863 he painted icons and wall-paintings by commission for the Society for the Encouragement of Artists. In 1864 he began attending the Imperial Academy of Arts, and met the painter Ivan Kramskoi.[7] In 1869 he was awarded a small gold medal for his painting Job and His Friends. He also met the critic Vladimir Stasov and painted a portrait of Vera Shevtsova, his future wife.[5]

_-_Volga_Boatmen_(1870-1873).jpg)

Repin traveled to the Volga River in 1870 to sketch landscapes and studies of barge haulers (Repin House and the Repin Museum on the Volga commemorate this sojourn). The following year he was awarded a large gold medal for his painting The Raising of Jairus' Daughter. He married Vera Shevtsova in 1872 and met Pavel Tretyakov, who purchased some of Repin's first works. Repin's first daughter, Vera, was born the same year. During this time, he worked on the painting Barge Haulers on the Volga, commissioned by Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich. The painting was completed in 1873.[5]

In an 1872 letter to Stasov, Repin wrote: "Now it is the peasant who is the judge and so it is necessary to represent his interests. (That is just the thing for me, since I am myself, as you know, a peasant, the son of a retired soldier who served twenty-seven hard years in Nicholas I's army.)"[8] In 1873 Repin traveled to Italy and France with his family. His second daughter, Nadezhda, was born in 1874.[9]

Career

1870s–1880s

In 1874–1876 he contributed to the Salon in Paris and to the exhibitions of the Itinerants' Society in Saint Petersburg.[10] While in France he became familiar with the impressionists and the debate over a new direction in art.[11] Though he admired some impressionist techniques, especially their depictions of light and color, he felt their work lacked moral or social purpose, key factors in his own art.[4]

Repin earned the title of academician in 1876 for his painting Sadko in the Underwater Kingdom. His son Yury was born the following year. He moved to Moscow that year, and produced a wide variety of works including portraits of Arkhip Kuindzhi and Ivan Shishkin. In 1878 he befriended Leo Tolstoy and the painter Vasily Surikov. His third daughter, Tatyana, was born in 1880.[10] He frequented the art circle of Savva Mamontov, which gathered at Abramtsevo, his estate near Moscow. Here Repin met many of the leading painters of the day, including Vasily Polenov, Valentin Serov, and Mikhail Vrubel.[12] In 1882 he and Vera divorced; they maintained a friendly relationship afterwards.[13]

Repin's contemporaries often commented on his special ability of capturing peasant life in his works. In an 1876 letter to Stasov, Kramskoi wrote: "Repin is capable of depicting the Russian peasant exactly as he is. I know many artists who have painted peasants, some of them very well, but none of them ever came close to what Repin does."[14] Leo Tolstoy later stated that Repin "depicts the life of the people much better than any other Russian artist."[4] He was praised for his ability to reproduce human life with powerful and vivid force.[14]

In 1880 he traveled to Zaporozhye to gather material for the painting Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks. In 1883 he traveled around Western Europe with Vladimir Stasov. Repin's painting Religious Procession in Kursk Province was shown at the eleventh Itinerants' Society Exhibition. In 1885 his painting Ivan the Terrible and His Son was shown at the 12th Itinerants' Society Exhibition. In 1886, he traveled to the Crimea with Arkhip Kuinji, and produced drawings and sketches on Biblical subjects.

In 1887 he visited Austria, Italy, and Germany, and retired from the board of the Itinerants' Society. He painted two portraits of Leo Tolstoy at Yasnaya Polyana that year and made preparations for his painting Leo Tolstoy Ploughing, and painted Alexander Pushkin on the Shore of the Black Sea (in collaboration with Ivan Aivazovsky).[15] In 1888 he traveled to Southern Russia and the Caucasus, where he did sketches and studies of descendants of the Zaporozhian Cossacks. In 1889 he traveled to Paris to see the World Exhibition and then visited London, Zurich, and Munich with Stasov.[16]

Most of Repin's finest portraits were produced in the 1880s. Through the presentation of real faces, these portraits express the rich, tragical, and hopeful spirit of the period. His portraits of Aleksey Pisemsky (1880), Modest Mussorgsky (1881), and others created throughout the decade have become familiar to whole generations of Russians. Each is completely lifelike, conveying the transient, changeable nature of the sitter's state of mind. They give an intense embodiment of both the physical and spiritual life of the people who sat for him.[17]

1890s

In 1890 he was given a government commission to work on the creation of a new statute for the Academy of Arts. In 1891 he resigned from the Itinerants' Society in protest against a new statute that restricted the rights of young artists. An exhibition of works by Repin and Shishkin was held in the Academy of Arts, including Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks. In 1892 he held a one-man exhibition at the History Museum in Moscow. In 1893 he visited academic art schools in Warsaw, Kraków, Munich, Vienna, and Paris to observe and study teaching methods. He spent the winter in Italy and published his essays Letters on Art.[18]

In 1894 he began teaching a class at the Higher Art School attached to the Academy of Arts, a position he held, off and on, until 1907.[19] In 1895 he painted portraits of Emperor Nicholas II, and Princess Maria Tenisheva. In 1896 he attended the All-Russian Exhibition in Nizhni Novgorod. His paintings were exhibited in Saint Petersburg, at the Exhibition of Works of Creative Art. His paintings from this year included The Duel and Don Juan and Dona Anna. In 1897 he rejoined the Itinerants' Society, and was appointed rector of the Higher Artistic School for a year. In 1898 he traveled to the Holy Land, and painted the icon Carrying the Cross for the Russian Orthodox Alexander Nevsky Cathedral in Jerusalem. After returning to Russia, he attended Pavel Tretyakov's funeral. In 1899 he joined the editorial board of the magazine World of Art, but soon quit.

In 1900 he met Nordman. Repin was captivated by her and they went to live in her home, Penaty (the Penates), in Kuokkala in Finland.[20] The couple would invite notable artists from Russia every Wednesday as their new home was only an hour by train from St Petersburg.[21] The Wednesday gatherings enabled Repin to put together an "album" of paintings for Nordman. He created portraits of the guests, each of which was labelled with their name, their profession and occasionally their autograph. Nordman's hospitality was well known and visitors included the writers Maxim Gorky and Aleksandr Kuprin; artists Vasily Polenov, Isaak Brodsky and Nicolai Fechin as well as poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, philosopher Vasily Rozanov and scientist Vladimir Bekhterev. Nordman was the keeper of this album as it was readied for display at World Exhibition in Italy in 1911.[22] Repin was to describe Nordman as the "love of his life".[21] The Penates became an important artistic and literary gathering place in the early 20th century.[19]

1900–1915

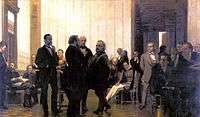

In 1900 he took his common-law wife Natalia Nordman to the World Exhibition in Paris, where he served as a painting judge. He visited Munich, the Tyrol, and Prague, and painted Natalia Nordman in a Tyrolese Hat and In the Sunlight: Portrait of Nadezhda Repina. In 1901 he was awarded the Legion of Honor. His painting Get Thee Behind Me, Satan! was shown at the 29th Itinerants' Society Exhibition. In 1902–1903 his works included the paintings Ceremonial Meeting of the State Council and What a Freedom!, over forty portrait studies, and portraits of Sergei Witte and Vyacheslav von Plehve.[23] Ceremonial Meeting of the State Council was the most demanding work commissioned by Repin, requiring numerous studies of the 100 councilors depicted, and the help of two of Repin's pupils.[24]

(1906–1911)

In 1904 he gave a speech at a memorial gathering for the artist Vasily Vereshchagin. He painted a portrait of the writer Leonid Andreyev and his work The Death of the Cossack Squadron Commander Zinovyev. He made sketches depicting government troops opening fire on a peaceful demonstration on 9 December 1905.[23] During 1905 Repin participated in many protests against bloodshed and Tsarist repressions, and tried to convey his impressions of these emotionally and politically charged events in his paintings.[25]

He also did sketches for portraits of Maxim Gorky and Vladimir Stasov and two portraits of Natalia Nordman. In 1907 he resigned from the Academy of Arts, visited Chuguyev and the Crimea, and wrote reminiscences of Vladimir Stasov. In 1908 he publicly denounced capital punishment in Russia. He illustrated Leonid Andreyev's story The Seven Who Were Hanged, and his painting The Cossacks from the Black Sea Coast was exhibited at the Itinerants' Society Exhibition. In 1909 he painted Gogol Burning the Manuscript of the Second Part of Dead Souls, and in 1910, portraits of Pyotr Stolypin, and the children's writer and poet Korney Chukovsky.[23]

In 1911 he traveled with Nordman to the World Exhibition in Italy, where his painting 17 October 1905 and his portraits were displayed in their own separate room. He wrote his reminiscences of Leo Tolstoy, gave a speech on artistic education, and painted Alexander Pushkin at the Lyceum Speech-Day, 8 January 1815. In 1912 he produced paintings related to the centenary of Napoleon's invasion of Russia. In 1913 he worked on restoring his painting Ivan the Terrible and His Son. In 1914 Natalia Nordman died in Locarno, and Repin attended her funeral there, afterwards going to Italy, before returning home to the Penates.[26]

Later life

.jpg)

In 1916 Repin worked on his book of reminiscences, Far and Near, with the assistance of Korney Chukovsky. He welcomed the Russian Revolution of February 1917. He painted a portrait of Alexander Kerensky, and The Slaves of Imperialism (a new version of the painting Barge Haulers on the Volga). In 1918 the frontier between Russia and Finland was closed, meaning Repin's estate was in Finland. In 1919 he donated his collection of works by Russian artists and his own works to the Finnish National Gallery in Helsinki, and in 1920 honorary celebrations of Repin were held by artistic circles in Finland. In 1921–1922 he painted The Ascent of Elijah the Prophet and Christ and Mary Magdalene (The Morning of the Resurrection).[27]

In 1923 Repin held a one-man exhibition in Prague. Celebrations were given in 1924 in Kuokkala to mark Repin's 80th birthday, and an exhibition of his works was held in Moscow. In 1925 a jubilee exhibition of his works was held in the Russian Museum in Leningrad, and his painting Calvary was shown in Oslo. In 1926 he declined an offer to move to Leningrad but donated three sketches devoted to the Revolution of 1905 and the portrait of Alexander Kerensky to the Museum of the Revolution of 1905 in that city. In 1928–29 he continued working on the painting The Hopak Dance (The Zaporozhye Cossacks Dancing), begun in 1926. Repin died in 1930, and was buried at the Penates.[28] His work was held up as an example to Soviet painters after his death. After the Finnish town of Kuokkala was annexed by the Soviet Union, in 1948 it was renamed Repino in his honor. The Penates also became a museum in 1940.[4]

Artistic work

Creativity

Repin persistently searched for new techniques and content to give his work more fullness and depth.[29] Repin had a set of favorite subjects, and a limited circle of people whose portraits he painted. But he had a deep sense of purpose in his aesthetics, and had the great artistic gift to sense the spirit of the age and its reflection in the lives and characters of individuals.[1] Repin's search for truth and for an ideal led him in various directions artistically, influenced by hidden aspects of social and spiritual experiences as well as national culture. Like most Russian realists of his times, Repin often based his works on dramatic conflicts, drawn from contemporary life or history. He also used mythological images with a strong sense of purpose; some of his religious paintings are among his greatest.[3]

His method was the reverse of the general approach of impressionism. He produced works slowly and carefully. They were the result of close and detailed study. With some of his paintings, he made one hundred or more preliminary sketches. He was never satisfied with his works, and often painted multiple versions, years apart. He also changed and adjusted his methods constantly in order to obtain more effective arrangement, grouping and coloristic power.[30] Repin's style of portraiture was unique, but owed something to the influence of Eduard Manet and Diego Velázquez.[24]

Ukrainian cultural influence

In the 1870s to 1880s he visited Chuguyev and gathered materials for his future works. There, he painted his Archdeacon.[31]

Paintings of Repin inspired by Ukrainian culture include:

- Man with a bad eye (1876)

- Ukrainian girl by the fence (1876)

- Mohnachi village near Chuguyev (1877)

- Portret of M. Murashko (1877)

- Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks (1880–1891, two versions: St. Petersburg, and Kharkiv)

- Vechornytsi (1881)

- Ukrainian village woman (1886)

- Taras Shevchenko's portrait (1888)

- Haydamaka (1902)

- Cossacks on the Black Sea (1908)

- Prometheus (1910, after T. Shevchenko's poem)

- Hopak (1930)

Repin was a member of the committee, set up to create a monument to painter-poet Taras Shevchenko whom he called an "apostle of freedom". He illustrated novels such as Taras Bulba and Sorochinsky Fair by Nikolai Gogol (1872–82) and Zaporissya in the remains of ancient legends and people by Dmytro Yavornytsky (1887), and drew numerous sketches of architecture as well as different popular aspects of Ukrainian culture. Repin's sphere of knowledge included a number of prominent thinkers of the time, including Marko Kropyvnytskyi, Mykola Murashko, and Dmytro Yavornytsky.

Repin helped the committee of the Visual Arts Union in Mykolaiv. He was also an honorary member of Literature and Art Union, as well as Union of the Antiquities and Art in Kiev. He supported numerous painters, Murashko's art schools in Kiev, M. Rajevska-Ivanova in Kharkiv, and the Art school in Odessa.[32]

In one of his last letters he wrote: "kind, dear compatriots […] I ask you to believe in the sense of my devotion and endless regret that I can't move to live in a sweet, joyful Ukraine […] Loving you from the childhood, Ilya Repin". The painter was buried by the "Chuguyev's hill", a place at the end of his property in Penates.[31]

Legacy

Repin was the first Russian artist to achieve European fame using specifically Russian themes.[4] His 1873 painting Barge Haulers on the Volga, radically different from previous Russian paintings, made him the leader of a new movement of critical realism in Russian art.[33] He chose nature and character over academic formalism. The triumph of this work was widespread, and it was praised by contemporaries like Vladimir Stasov and Fyodor Dostoyevsky. The paintings show his feeling of personal responsibility for the hard life of the common people and the destiny of Russia.[29] In the 1880s he produced many of his most famous works, and joined the Itinerants' Society.[34]

Gallery

- Paintings

Slavic Composers (1871)

Slavic Composers (1871) The Revival of the Daughter of Jairus

The Revival of the Daughter of Jairus

(1871, after Mark 5,22–43) Sadko (1876)

Sadko (1876) Portrait of M. P. Mussorgsky (1881)

Portrait of M. P. Mussorgsky (1881) Alexander III receiving rural district elders in the yard of Petrovsky Palace in Moscow (1886)

Alexander III receiving rural district elders in the yard of Petrovsky Palace in Moscow (1886) They Did Not Expect Him (c. 1886)

They Did Not Expect Him (c. 1886) Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka during the composition of the opera "Ruslan and Ludmila" (1887)

Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka during the composition of the opera "Ruslan and Ludmila" (1887) The Surgeon Evgeny Vasilyevich Pavlov in the Operating Theater (1888)

The Surgeon Evgeny Vasilyevich Pavlov in the Operating Theater (1888) Portrait of Composer and Chemist Alexander Borodin (1888)

Portrait of Composer and Chemist Alexander Borodin (1888) Portrait of Composer César Antonovich Cui (1890)

Portrait of Composer César Antonovich Cui (1890)_by_Ilya_Repin_-_%D0%9D%D0%B5%D0%B0%D0%BF%D0%BE%D0%BB%D0%B8%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%BA%D0%B0.jpg) Neapolitan Woman (1894)

Neapolitan Woman (1894) Portrait of Countess Natalia Petrovna Golovina (1896)

Portrait of Countess Natalia Petrovna Golovina (1896).jpg) The Blonde Woman (1898, portrait of Tevashova)

The Blonde Woman (1898, portrait of Tevashova) Ceremonial Sitting of the State Council on 7 May 1901 Marking the Centenary of its Foundation (1903)

Ceremonial Sitting of the State Council on 7 May 1901 Marking the Centenary of its Foundation (1903) What Freedom! (1903)

What Freedom! (1903) Gogol burning the manuscript of the second part of "Dead Souls" (1909)

Gogol burning the manuscript of the second part of "Dead Souls" (1909) Bolshevik (1918)

Bolshevik (1918)

References

- Sternine & Kirillina 2011, p. 13.

- Parker, Fan; Stephen Jan Parker (1980). Russia on Canvas: Ilya Repin. Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 1. ISBN 0-271-00252-2.

- Sternine & Kirillina 2011, p. 14.

- Chilvers 2004, p. 588.

- Sternine & Kirillina 2011, p. 181.

- Buchastaya S. I., Sabodash E. N., Shevchenko O. A. (2014). New findings on I. Y. Repin's genealogy and a new view on the artist's origin article from the Contemporary Issues of Local and World History magazine at the I. Y. Repin's Memorial Art Museum website, pp. 183—187 (in Russian) ISSN 2077-7280

- Sternine & Kirillina 2011, p. 18.

- Sternine & Kirillina 2011, pp. 14–15.

- Sternine & Kirillina 2011, pp. 181–182.

- Sternine & Kirillina 2011, pp. 182–183.

- Sternine & Kirillina 2011, p. 22.

- Sternine & Kirillina 2011, p. 25.

- Sternine & Kirillina 2011, p. 130.

- Sternine & Kirillina 2011, p. 35.

- Sternine & Kirillina 2011, pp. 183–184.

- Sternine & Kirillina 2011, p. 184.

- Sternine & Kirillina 2011, p. 78.

- Sternine & Kirillina 2011, pp. 185–186.

- Bolton 2010, p. 115.

- Apresyan, A. (2020-01-25). "5 eccentricities of great Russian painters". Russia Beyond the Headlines. Retrieved 2020-02-19.

- Daniel Coenn (28 July 2013). Repin: Drawings. Lulu.com. pp. 3–. ISBN 978-1-304-27417-5.

- Portraits from the ‘Album of Natalia Nordman-Severova’, Nimrah.ru, Retrieved 21 November 2016

- Sternine & Kirillina 2011, pp. 187–189.

- Leek 2005, p. 63.

- Sternine & Kirillina 2011, p. 121.

- Sternine & Kirillina 2011, pp. 189–190.

- Sternine & Kirillina 2011, pp. 190–191.

- Sternine & Kirillina 2011, p. 191.

- Sternine & Kirillina 2011, p. 21.

- Sternine & Kirillina 2011, p. 30.

- "Шукач | Мемориальный музей - усадьба И.Е.Репина в Чугуеве". www.shukach.com. Retrieved 2017-01-03.

- svist, igor. "Ілля Рєпін: закоханий в Україну / Віртуальні виставки / РОУНБ (РДОБ) - Рівненська обласна універсальна наукова бібліотека, Комунальний заклад Рівненської обласної ради". libr.rv.ua. Retrieved 2017-01-03.

- Bolton 2010, p. 114.

- Sternine & Kirillina 2011, p. 27.

Bibliography

- Sternine, Grigori; Kirillina, Elena (2011). Ilya Repin. Parkstone Press. ISBN 978-1-78042-733-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chilvers, Ian (2004). The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860476-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Leek, Peter (2005). Russian Painting. Parkstone Press. ISBN 978-1-85995-939-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bolton, Roy (2010). Views of Russia & Russian Works on Paper. Sphinx Books. ISBN 978-1-907200-05-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ilya Yefimovich Repin. |

- Parker, Fan; Stephen Jan Parker (1980). Russia on Canvas: Ilya Repin. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-271-00252-2.

- Sternin, Grigory (1985). Ilya Repin: Painting Graphic Arts. Leningrad: Auroras.

- Valkenier, Elizabeth Kridl (1990). Ilya Repin and the World of Russian Art. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-06964-2.

- Marcadé, Valentine (1990). Art d'Ukraine. Lausanne: L'Age d'Homme. ISBN 978-2-8251-0031-8.

- Jackson, David, The Russian Vision: The Art of Ilya Repin (Schoten, Belgium, 2006) ISBN 9085860016

- Karageorgevich, Prince Bojidar, "Professor Repin," in the Magazine of Art, xxiii. p. 783 (1899)

- Prymak, Thomas M., "A Painter from Ukraine: Ilya Repin," Canadian Slavonic Papers, LV, 1–2 (2013), 19–43.