Kamarina, Sicily

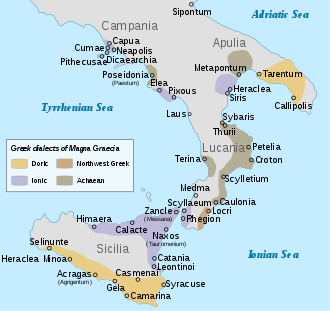

Kamarina (Greek: Καμάρινα, Latin, Italian, & Sicilian: Camarina) was an ancient city on the southern coast of Sicily in southern Italy. The ruins of the site and an archaeological museum are located south of the modern town Scoglitti, a frazione of the comune Vittoria in the province of Ragusa.

Καμάρινα (in Greek) Camarina (in Latin, Italian, and Sicilian) | |

The House of the Altar | |

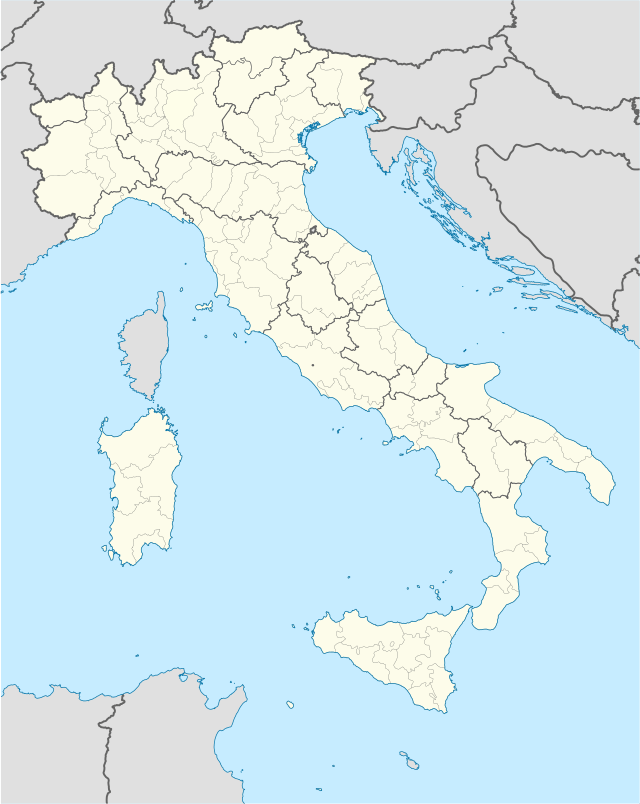

Shown within Italy | |

| Alternative name | Camarina |

|---|---|

| Location | Scoglitti, Province of Ragusa, Sicily, Italy |

| Coordinates | 36°52′18″N 14°26′51″E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Builder | Syracuse |

| Founded | 599 BC |

| Abandoned | 853 AD |

| Cultures | Greek, Roman |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Ownership | Public |

| Management | Soprintendenza BB.CC.AA. di Ragusa |

| Public access | Yes |

| Website | Museo Archeologico Regionale di Camarina (in Italian) |

History

It was founded by Syracuse in 599 BC, but destroyed by the mother city in 552 BC.[1] Its remains are today in the municipality of Ragusa.

The Geloans, however, founded it anew in 461 BC, under the Olympic charioteer Psaumis of Camarina. It seems to have been in general hostile to Syracuse, but, though an ally of Athens in 427 BC, it gave some slight help to Syracuse in 415–413 BC. It was destroyed by the Carthaginians in 405 BC, restored by Timoleon in 339 BC after its abandonment by Dionysius' order, but in 258 BC fell into the hands of the Romans.[1]

Its complete destruction dates from AD 853. The site of the ancient city is among rapidly shifting sandhills, and the lack of stone in the neighborhood has led to its buildings being used as a quarry even by the inhabitants of Gela, so that nothing is now visible above ground but a small part of the wall of the temple of Athena and a few foundations of houses; portions of the city wall have been traced by excavation, and the necropolis has been carefully explored.[1]

Democracy in Kamarina

When the Geloans re-founded the city in 461, they appear to have done so with a democratic constitution (alongside a more general institution of democracies in the wake of the Common Resolution: Diod. 11.68.5). In 415 Thucydides describes a public meeting (syllogos: 6.75-88) at which the city decided for neutrality (though it later voted to reverse this decision: 7.33.1, 7.58.1).

A series of more than 140 lead plates, discovered around the Temple of Athena, and with information about citizens written on them, has suggested to some that Kamarina used allotment to select jurors and city officials (as Athens and other democratic city-states did). These may, however, have had some other use, for example, as a register of citizens for military purposes.[2]

The marsh

Just before the Carthaginians razed Kamarina in the 5th century BC, the Kamarinians were plagued with a mysterious disease. The marsh of Kamarina had protected the city from its hostile neighbors to the north. It was suspected that the marsh was the source of the strange illness and the idea of draining the marsh to end the epidemic became popular (the germ theory of disease was millennia in the future, but some people associated swamps with disease). The town oracle was consulted. The oracle advised the leaders not to drain the marsh, suggesting the plague would pass with time. But the discontent was widespread and the leaders opted to drain the marsh against the oracle's advice. Once it was dry, there was nothing stopping the Carthaginian army from advancing. They marched across the newly drained marsh and razed the city, killing every last inhabitant.

The story of the marsh is told by the Roman geographer Strabo and repeated by Carl Sagan in Pale Blue Dot. The story of the city is recounted by the latter author as a lesson: that action guided by fear and ignorance often intensifies the problems it seeks to ameliorate.

Remains

Modern remains are scanty. They include archaic tombs (seventh century BC) and ruins of a temple of Athena. Nearby are tombs of a necropolis from the fifth-fourth century BC. Part of the remains are now in the archaeological museum of Syracuse. The archaeological park includes the remains of a "Hamman qbel Jamaa" - public baths used before entering the mosque, one of only two known on the island.[3]

Gallery

The House of the Altar

The House of the Altar A part of the wall of the temple of Athena

A part of the wall of the temple of Athena Ruins of the temple of Athena

Ruins of the temple of Athena

See also

References

-

- See E. Robinson, Democracy Beyond Athens (Cambridge, 2011) 97-100.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-06-09. Retrieved 2011-08-12.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)