Running

Running is a method of terrestrial locomotion allowing humans and other animals to move rapidly on foot. Running is a type of gait characterized by an aerial phase in which all feet are above the ground (though there are exceptions).[1] This is in contrast to walking, where one foot is always in contact with the ground, the legs are kept mostly straight and the center of gravity vaults over the stance leg or legs in an inverted pendulum fashion.[2] A feature of a running body from the viewpoint of spring-mass mechanics is that changes in kinetic and potential energy within a stride occur simultaneously, with energy storage accomplished by springy tendons and passive muscle elasticity.[3] The term running can refer to any of a variety of speeds ranging from jogging to sprinting.

.jpg)

Running in humans is associated with improved health and life expectancy.[4]

It is assumed that the ancestors of humankind developed the ability to run for long distances about 2.6 million years ago, probably in order to hunt animals.[5] Competitive running grew out of religious festivals in various areas. Records of competitive racing date back to the Tailteann Games in Ireland between 632 BCE and 1171 BCE,[6][7][8] while the first recorded Olympic Games took place in 776 BCE. Running has been described as the world's most accessible sport.[9]

History

It is thought that human running evolved at least four and a half million years ago out of the ability of the ape-like Australopithecus, an early ancestor of humans, to walk upright on two legs.[10]

Early humans most likely developed into endurance runners from the practice of persistence hunting of animals, the activity of following and chasing until a prey is too exhausted to flee, succumbing to "chase myopathy" (Sears 2001), and that human features such as the nuchal ligament, abundant sweat glands, the Achilles tendons, big knee joints and muscular glutei maximi, were changes caused by this type of activity (Bramble & Lieberman 2004, et al.).[11][12][13] The theory as first proposed used comparative physiological evidence and the natural habits of animals when running, indicating the likelihood of this activity as a successful hunting method. Further evidence from observation of modern-day hunting practice also indicated this likelihood (Carrier et al. 1984). [13][14] According to Sears (p. 12) scientific investigation (Walker & Leakey 1993) of the Nariokotome Skeleton provided further evidence for the Carrier theory.[15]

Competitive running grew out of religious festivals in various areas such as Greece, Egypt, Asia, and the East African Rift in Africa. The Tailteann Games, an Irish sporting festival in honor of the goddess Tailtiu, dates back to 1829 BCE, and is one of the earliest records of competitive running. The origins of the Olympics and Marathon running are shrouded by myth and legend, though the first recorded games took place in 776 BCE.[16] Running in Ancient Greece can be traced back to these games of 776 BCE.

...I suspect that the sun, moon, earth, stars, and heaven, which are still the gods of many barbarians, were the only gods known to the aboriginal Hellenes. Seeing that they were always moving and running, from their running nature they were called gods or runners (Thus, Theontas)...

Description

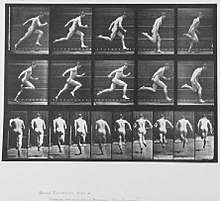

Running gait can be divided into two phases in regard to the lower extremity: stance and swing.[18][19][20][21] These can be further divided into absorption, propulsion, initial swing and terminal swing. Due to the continuous nature of running gait, no certain point is assumed to be the beginning. However, for simplicity, it will be assumed that absorption and footstrike mark the beginning of the running cycle in a body already in motion.

Footstrike

Footstrike occurs when a plantar portion of the foot makes initial contact with the ground. Common footstrike types include forefoot, midfoot and heel strike types.[22][23][24] These are characterized by initial contact of the ball of the foot, ball and heel of the foot simultaneously and heel of the foot respectively. During this time the hip joint is undergoing extension from being in maximal flexion from the previous swing phase. For proper force absorption, the knee joint should be flexed upon footstrike and the ankle should be slightly in front of the body.[25] Footstrike begins the absorption phase as forces from initial contact are attenuated throughout the lower extremity. Absorption of forces continues as the body moves from footstrike to midstance due to vertical propulsion from the toe-off during a previous gait cycle.

Midstance

Midstance is defined as the time at which the lower extremity limb of focus is in knee flexion directly underneath the trunk, pelvis and hips. It is at this point that propulsion begins to occur as the hips undergo hip extension, the knee joint undergoes extension and the ankle undergoes plantar flexion. Propulsion continues until the leg is extended behind the body and toe off occurs. This involves maximal hip extension, knee extension and plantar flexion for the subject, resulting in the body being pushed forward from this motion and the ankle/foot leaves the ground as initial swing begins.

Propulsion phase

Most recent research, particularly regarding the footstrike debate, has focused solely on the absorption phases for injury identification and prevention purposes. The propulsion phase of running involves the movement beginning at midstance until toe off.[19][20][26] From a full stride length model however, components of the terminal swing and footstrike can aid in propulsion.[21][27] Set up for propulsion begins at the end of terminal swing as the hip joint flexes, creating the maximal range of motion for the hip extensors to accelerate through and produce force. As the hip extensors change from reciporatory inhibitors to primary muscle movers, the lower extremity is brought back toward the ground, although aided greatly by the stretch reflex and gravity.[21] Footstrike and absorption phases occur next with two types of outcomes. This phase can be only a continuation of momentum from the stretch reflex reaction to hip flexion, gravity and light hip extension with a heel strike, which does little to provide force absorption through the ankle joint.[26][28][29] With a mid/forefoot strike, loading of the gastro-soleus complex from shock absorption will serve to aid in plantar flexion from midstance to toe-off.[29][30] As the lower extremity enters midstance, true propulsion begins.[26] The hip extensors continue contracting along with help from the acceleration of gravity and the stretch reflex left over from maximal hip flexion during the terminal swing phase. Hip extension pulls the ground underneath the body, thereby pulling the runner forward. During midstance, the knee should be in some degree of knee flexion due to elastic loading from the absorption and footstrike phases to preserve forward momentum.[31][32][33] The ankle joint is in dorsiflexion at this point underneath the body, either elastically loaded from a mid/forefoot strike or preparing for stand-alone concentric plantar flexion. All three joints perform the final propulsive movements during toe-off.[26][28][29][30] The plantar flexors plantar flex, pushing off from the ground and returning from dorsiflexion in midstance. This can either occur by releasing the elastic load from an earlier mid/forefoot strike or concentrically contracting from a heel strike. With a forefoot strike, both the ankle and knee joints will release their stored elastic energy from the footstrike/absorption phase.[31][32][33] The quadriceps group/knee extensors go into full knee extension, pushing the body off of the ground. At the same time, the knee flexors and stretch reflex pull the knee back into flexion, adding to a pulling motion on the ground and beginning the initial swing phase. The hip extensors extend to maximum, adding the forces pulling and pushing off of the ground. The movement and momentum generated by the hip extensors also contributes to knee flexion and the beginning of the initial swing phase.

Swing phase

Initial swing is the response of both stretch reflexes and concentric movements to the propulsion movements of the body. Hip flexion and knee flexion occur beginning the return of the limb to the starting position and setting up for another footstrike. Initial swing ends at midswing, when the limb is again directly underneath the trunk, pelvis and hip with the knee joint flexed and hip flexion continuing. Terminal swing then begins as hip flexion continues to the point of activation of the stretch reflex of the hip extensors. The knee begins to extend slightly as it swings to the anterior portion of the body. The foot then makes contact with the ground with footstrike, completing the running cycle of one side of the lower extremity. Each limb of the lower extremity works opposite to the other. When one side is in toe-off/propulsion, the other hand is in the swing/recovery phase preparing for footstrike.[18][19][20][21] Following toe-off and the beginning of the initial swing of one side, there is a flight phase where neither extremity is in contact with the ground due to the opposite side finishing terminal swing. As the footstrike of the one hand occurs, initial swing continues. The opposing limbs meet with one in midstance and midswing, beginning the propulsion and terminal swing phases.

Upper extremity function

Upper extremity function serves mainly in providing balance in conjunction with the opposing side of the lower extremity.[19] The movement of each leg is paired with the opposite arm which serves to counterbalance the body, particularly during the stance phase.[26] The arms move most effectively (as seen in elite athletes) with the elbow joint at an approximately 90 degrees or less, the hands swinging from the hips up to mid chest level with the opposite leg, the Humerus moving from being parallel with the trunk to approximately 45 degrees shoulder extension (never passing the trunk in flexion) and with as little movement in the transverse plane as possible.[34] The trunk also rotates in conjunction with arm swing. It mainly serves as a balance point from which the limbs are anchored. Thus trunk motion should remain mostly stable with little motion except for slight rotation as excessive movement would contribute to transverse motion and wasted energy.

Footstrike debate

Recent research into various forms of running has focused on the differences, in the potential injury risks and shock absorption capabilities between heel and mid/forefoot footstrikes. It has been shown that heel striking is generally associated with higher rates of injury and impact due to inefficient shock absorption and inefficient biomechanical compensations for these forces.[22] This is due to forces from a heel strike traveling through bones for shock absorption rather than being absorbed by muscles. Since bones cannot disperse forces easily, the forces are transmitted to other parts of the body, including ligaments, joints and bones in the rest of the lower extremity all the way up to the lower back.[35] This causes the body to use abnormal compensatory motions in an attempt to avoid serious bone injuries.[36] These compensations include internal rotation of the tibia, knee and hip joints. Excessive amounts of compensation over time have been linked to higher risk of injuries in those joints as well as the muscles involved in those motions.[28] Conversely, a mid/forefoot strike has been associated with greater efficiency and lower injury risk due to the triceps surae being used as a lever system to absorb forces with the muscles eccentrically rather than through the bone.[22] Landing with a mid/forefoot strike has also been shown to not only properly attenuate shock but allows the triceps surae to aid in propulsion via reflexive plantarflexion after stretching to absorb ground contact forces.[27][37] Thus a mid/forefoot strike may aid in propulsion. However, even among elite athletes there are variations in self selected footstrike types.[38] This is especially true in longer distance events, where there is a prevalence of heel strikers.[39] There does tend however to be a greater percentage of mid/forefoot striking runners in the elite fields, particularly in the faster racers and the winning individuals or groups.[34] While one could attribute the faster speeds of elite runners compared to recreational runners with similar footstrikes to physiological differences, the hip and joints have been left out of the equation for proper propulsion. This brings up the question as to how heel striking elite distance runners are able to keep up such high paces with a supposedly inefficient and injurious foot strike technique.

Stride length, hip and knee function

Biomechanical factors associated with elite runners include increased hip function, use and stride length over recreational runners.[34][40] An increase in running speeds causes increased ground reaction forces and elite distance runners must compensate for this to maintain their pace over long distances.[41] These forces are attenuated through increased stride length via increased hip flexion and extension through decreased ground contact time and more force being used in propulsion.[41][42][43] With increased propulsion in the horizontal plane, less impact occurs from decreased force in the vertical plane.[44] Increased hip flexion allows for increased use of the hip extensors through midstance and toe-off, allowing for more force production.[26] The difference even between world-class and national-level 1500-m runners has been associated with more efficient hip joint function.[45] The increase in velocity likely comes from the increased range of motion in hip flexion and extension, allowing for greater acceleration and velocity. The hip extensors and hip extension have been linked to more powerful knee extension during toe-off, which contributes to propulsion.[34] Stride length must be properly increased with some degree of knee flexion maintained through the terminal swing phases, as excessive knee extension during this phase along with footstrike has been associated with higher impact forces due to braking and an increased prevalence of heel striking.[46] Elite runners tend to exhibit some degree of knee flexion at footstrike and midstance, which first serves to eccentrically absorb impact forces in the quadriceps muscle group.[45][47][48] Secondly it allows for the knee joint to concentrically contract and provides major aid in propulsion during toe-off as the quadriceps group is capable of produce large amounts of force.[26] Recreational runners have been shown to increase stride length through increased knee extension rather than increased hip flexion as exhibited by elite runners, which serves instead to provide an intense braking motion with each step and decrease the rate and efficiency of knee extension during toe-off, slowing down speed.[40] Knee extension however contributes to additional stride length and propulsion during toe-off and is seen more frequently in elite runners as well.[34]

Good technique

Upright posture and slight forward lean

Leaning forward places a runner's center of mass on the front part of the foot, which avoids landing on the heel and facilitates the use of the spring mechanism of the foot. It also makes it easier for the runner to avoid landing the foot in front of the center of mass and the resultant braking effect. While upright posture is essential, a runner should maintain a relaxed frame and use their core to keep posture upright and stable. This helps prevent injury as long as the body is neither rigid nor tense. The most common running mistakes are tilting the chin up and scrunching shoulders.[49]

Stride rate and types

Exercise physiologists have found that the stride rates are extremely consistent across professional runners, between 185 and 200 steps per minute. The main difference between long- and short-distance runners is the length of stride rather than the rate of stride.[50][51]

During running, the speed at which the runner moves may be calculated by multiplying the cadence (steps per minute) by the stride length. Running is often measured in terms of pace[52] in minutes per mile or kilometer. Different types of stride are necessary for different types of running. When sprinting, runners stay on their toes bringing their legs up, using shorter and faster strides. Long distance runners tend to have more relaxed strides that vary.

Health benefits

Cardiovascular

While there exists the potential for injury while running (just as there is in any sport), there are many benefits. Some of these benefits include potential weight loss, improved cardiovascular and respiratory health (reducing the risk of cardiovascular and respiratory diseases), improved cardiovascular fitness, reduced total blood cholesterol, strengthening of bones (and potentially increased bone density), possible strengthening of the immune system and an improved self-esteem and emotional state.[53] Running, like all forms of regular exercise, can effectively slow[54] or reverse[55] the effects of aging. Even people who have already experienced a heart attack are 20% less likely to develop serious heart problems if more engaged in running or any type of aerobic activity.[56]

Although an optimal amount of vigorous aerobic exercise such as running might bring benefits related to lower cardiovascular disease and life extension, an excessive dose (e.g., marathons) might have an opposite effect associated with cardiotoxicity.[57]

Metabolic

Running can assist people in losing weight, staying in shape and improving body composition. Research suggests that the person of average weight will burn approximately 100 calories per mile run.[58] Running increases one's metabolism, even after running; one will continue to burn an increased level of calories for a short time after the run.[59] Different speeds and distances are appropriate for different individual health and fitness levels. For new runners, it takes time to get into shape. The key is consistency and a slow increase in speed and distance.[58] While running, it is best to pay attention to how one's body feels. If a runner is gasping for breath or feels exhausted while running, it may be beneficial to slow down or try a shorter distance for a few weeks. If a runner feels that the pace or distance is no longer challenging, then the runner may want to speed up or run farther.[60]

Mental

Running can also have psychological benefits, as many participants in the sport report feeling an elated, euphoric state, often referred to as a "runner's high".[61] Running is frequently recommended as therapy for people with clinical depression and people coping with addiction.[62] A possible benefit may be the enjoyment of nature and scenery, which also improves psychological well-being[63] (see Ecopsychology § Practical benefits).

In animal models, running has been shown to increase the number of newly created neurons within the brain.[64] This finding could have significant implications in aging as well as learning and memory. A recent study published in Cell Metabolism has also linked running with improved memory and learning skills.[65]

Running is an effective way to reduce stress, anxiety, depression, and tension. It helps people who struggle with seasonal affective disorder by running outside when it is sunny and warm. Running can improve mental alertness and also improves sleep. Both research and clinical experience have shown that exercise can be a treatment for serious depression and anxiety even some physicians prescribe exercise to most of their patients. Running can have a longer lasting effect than anti-depressants.[66]

Injuries

High impact

Many injuries are associated with running because of its high-impact nature. Change in running volume may lead to development of patellofemoral pain syndrome, iliotibial band syndrome, patellar tendinopathy, plica syndrome, and medial tibial stress syndrome. Change in running pace may cause Achilles Tendinitis, gastrocnemius injuries, and plantar fasciitis.[67] Repetitive stress on the same tissues without enough time for recovery or running with improper form can lead to many of the above. Runners generally attempt to minimize these injuries by warming up before exercise,[25] focusing on proper running form, performing strength training exercises, eating a well balanced diet, allowing time for recovery, and "icing" (applying ice to sore muscles or taking an ice bath).

Some runners may experience injuries when running on concrete surfaces. The problem with running on concrete is that the body adjusts to this flat surface running, and some of the muscles will become weaker, along with the added impact of running on a harder surface. Therefore, it is advised to change terrain occasionally – such as trail, beach, or grass running. This is more unstable ground and allows the legs to strengthen different muscles. Runners should be wary of twisting their ankles on such terrain. Running downhill also increases knee stress and should, therefore, be avoided. Reducing the frequency and duration can also prevent injury.

Barefoot running has been promoted as a means of reducing running related injuries,[68] but this remains controversial and a majority of professionals advocate the wearing of appropriate shoes as the best method for avoiding injury.[69] However, a study in 2013 concluded that wearing neutral shoes is not associated with increased injuries.[70]

Chafing

Another common, running-related injury is chafing, caused by repetitive rubbing of one piece of skin against another, or against an article of clothing. One common location for chafe to occur is the runner's upper thighs. The skin feels coarse and develops a rash-like look. A variety of deodorants and special anti-chafing creams are available to treat such problems. Chafe is also likely to occur on the nipple. There are a variety of home remedies that runners use to deal with chafing while running such as band-aids and using grease to reduce friction. Prevention is key which is why form fitting clothes are important.[71]

Iliotibial band syndrome

An iliotibial band is a muscle and tendon that is attached to the hip and runs the length of the thigh to attach to the upper part of the tibia, and the band is what helps the knee to bend. This is an injury that is located at the knee and shows symptoms of swelling outside the knee. Iliotibial band syndrome is also known as "runner's knee" or "jogger's knee" because it can be caused by jogging or running. Once pain or swelling is noticeable it is important to put ice on it immediately and it's recommended to rest the knee for better healing.[72] Most knee injuries can be treated by light activity and much rest for the knee. In more serious cases, arthroscopy is the most common to help repair ligaments but severe situations reconstructive surgery would be needed.[73] A survey was taken in 2011 with knee injuries being 22.7% of the most common injuries.[74]

Medial tibial stress syndrome

A more known injury is medial tibial stress syndrome (MTSS) which is the accurate name for shin splints. This is caused during running when the muscle is being overused along the front of the lower leg with symptoms that affect 2 to 6 inches of the muscle. Shin Splints have sharp, splinter-like pain, that is typically X-rayed by doctors but is not necessary for shin splints to be diagnosed. To help prevent shin splints it's commonly known to stretch before and after a workout session, and also avoid heavy equipment especially during the first couple of workout sessions.[75] Also to help prevent shin splints don't increase the intensity of a workout more than 10% a week.[76] To treat shin splints it's important to rest with the least amount of impact on your legs and apply ice to the area. A survey showed that shin splints 12.7% of the most common injuries in running with blisters being the top percentage at 30.9%.[74]

Events

Running is both a competition and a type of training for sports that have running or endurance components. As a sport, it is split into events divided by distance and sometimes includes permutations such as the obstacles in steeplechase and hurdles. Running races are contests to determine which of the competitors is able to run a certain distance in the shortest time. Today, competitive running events make up the core of the sport of athletics. Events are usually grouped into several classes, each requiring substantially different athletic strengths and involving different tactics, training methods, and types of competitors.

Running competitions have probably existed for most of humanity's history and were a key part of the ancient Olympic Games as well as the modern Olympics. The activity of running went through a period of widespread popularity in the United States during the running boom of the 1970s. Over the next two decades, as many as 25 million Americans were doing some form of running or jogging – accounting for roughly one tenth of the population.[77] Today, road racing is a popular sport among non-professional athletes, who included over 7.7 million people in America alone in 2002.[78]

Limits of speed

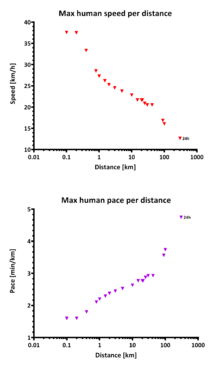

Footspeed, or sprint speed, is the maximum speed at which a human can run. It is affected by many factors, varies greatly throughout the population, and is important in athletics and many sports.

The fastest human footspeed on record is 44.7 km/h (12.4 m/s, 27.8 mph), seen during a 100-meter sprint (average speed between the 60th and the 80th meter) by Usain Bolt.[79]

Speed over increasing distance based on world record times

(see Category:Athletics (track and field) record progressions)

| Distance metres | Men m/s | Women m/s |

|---|---|---|

| 100 | 10.44 | 9.53 |

| 200 | 10.42 | 9.37 |

| 400 | 9.26 | 8.44 |

| 800 | 7.92 | 7.06 |

| 1,000 | 7.58 | 6.71 |

| 1,500 | 7.28 | 6.51 |

| 1,609 (mile) | 7.22 | 6.36 |

| 2,000 | 7.02 | 6.15 |

| 3,000 | 6.81 | 6.17 |

| 5,000 | 6.60 | 5.87 |

| 10,000 track | 6.34 | 5.64 |

| 10,000 road | 6.23 | 5.49 |

| 15,000 road | 6.02 | 5.38 |

| 20,000 track | 5.91 | 5.09 |

| 20,000 road | 6.02 | 5.30 |

| 21,097 Half marathon | 6.02 | 5.29 |

| 21,285 One hour run | 5.91 | 5.14 |

| 25,000 track | 5.63 | 4.78 |

| 25,000 road | 5.80 | 5.22 |

| 30,000 track | 5.60 | 4.72 |

| 30,000 road | 5.69 | 5.06 |

| 42,195 Marathon | 5.69 | 5.19 |

| 90,000 Comrades | 4.68 | 4.23 |

| 100,000 | 4.46 | 4.24 |

| 303,506 24-hour run | 3.513 | 2.82 |

Types

- Track

Track running events are individual or relay events with athletes racing over specified distances on an oval running track. The events are categorized as sprints, middle and long-distance, and hurdling.

- Road

Road running takes place on a measured course over an established road (as opposed to track and cross country running). These events normally range from distances of 5 kilometers to longer distances such as half marathons and marathons, and they may involve scores of runners or wheelchair entrants.

- Cross-country

Cross country running takes place over the open or rough terrain. The courses used for these events may include grass, mud, woodlands, hills, flat ground and water. It is a popular participatory sport and is one of the events which, along with track and field, road running, and racewalking, makes up the umbrella sport of athletics.

- Vertical

The majority of popular races do not incorporate a significant change in elevation as a key component of a course. There are several, disparate variations that feature significant inclines or declines. These fall into two main groups.

The naturalistic group is based on outdoor racing over geographical features. Among these are the cross country-related sports of fell running (a tradition associated with Northern Europe) and trail running (mainly ultramarathon distances), the running/climbing combination of skyrunning (organised by the International Skyrunning Federation with races across North America, Europe and East Asia) and the mainly trail- and road-centred mountain running (governed by the World Mountain Running Association and based mainly in Europe).

The second variety of vertical running is based on human structures, such as stairs and man-made slopes. The foremost type of this is tower running, which sees athletes compete indoors, running up steps within very tall structures such as the Eiffel Tower or Empire State Building.

Distances

Sprints

_wins_the_100_metres_race_-_ISTAF_2006_-_Berlin%2C_3_September.jpg)

Sprints are short running events in athletics and track and field. Races over short distances are among the oldest running competitions. The first 13 editions of the Ancient Olympic Games featured only one event – the stadion race, which was a race from one end of the stadium to the other.[80] There are three sprinting events which are currently held at the Olympics and outdoor World Championships: the 100 metres, 200 metres, and 400 metres. These events have their roots in races of imperial measurements which were later altered to metric: the 100 m evolved from the 100-yard dash,[81] the 200 m distances came from the furlong (or 1/8 of a mile),[82] and the 400 m was the successor to the 440-yard dash or quarter-mile race.[83]

At the professional level, sprinters begin the race by assuming a crouching position in the starting blocks before leaning forward and gradually moving into an upright position as the contest progresses and momentum is gained.[84] Athletes remain in the same lane on the running track throughout all sprinting events,[83] with the sole exception of the 400 m indoors. Races up to 100 m are largely focused upon acceleration to an athlete's maximum speed.[84] All sprints beyond this distance increasingly incorporate an element of endurance.[85] Human physiology dictates that a runner's near-top speed cannot be maintained for more than thirty seconds or so as lactic acid builds up, and leg muscles begin to be deprived of oxygen.[83]

The 60 metres is a common indoor event and it an indoor world championship event. Other less-common events include the 50 metres, 55 metres, 300 metres and 500 metres which are used in some high and collegiate competitions in the United States. The 150 metres, is rarely competed: Pietro Mennea set a world best in 1983,[86] Olympic champions Michael Johnson and Donovan Bailey went head-to-head over the distance in 1997,[87] and Usain Bolt improved Mennea's record in 2009.[86]

Middle distance

Middle distance running events are track races longer than sprints up to 3000 metres. The standard middle distances are the 800 metres, 1500 metres and mile run, although the 3000 metres may also be classified as a middle distance event.[88] The 880-yard run, or half-mile, was the forebear to the 800 m distance and it has its roots in competitions in the United Kingdom in the 1830s.[89] The 1500 m came about as a result of running three laps of a 500 m track, which was commonplace in continental Europe in the 1900s.[90]

Long distance

Examples of longer-distance running events are long distance track races, marathons, ultramarathons, and multiday races.

See also

References

- Rubenson, Jonas; Heliams, Denham B.; Lloyd, David G.; Fournier, Paul A. (22 May 2004). "Gait selection in the ostrich: mechanical and metabolic characteristics of walking and running with and without an aerial phase". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 271 (1543): 1091–1099. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2702. PMC 1691699. PMID 15293864.

- Biewener, A. A. 2003. Animal Locomotion. Oxford University Press, US. ISBN 978-0-19-850022-3, books.google.com

- Cavagna, G. A.; Saibene, F. P.; Margaria, R. (1964). "Mechanical Work in Running". Journal of Applied Physiology. 19 (2): 249–256. doi:10.1152/jappl.1964.19.2.249. PMID 14155290.

- Pedisic, Zeljko; Shrestha, Nipun; Kovalchik, Stephanie; Stamatakis, Emmanuel; Liangruenrom, Nucharapon; Grgic, Jozo; Titze, Sylvia; Biddle, Stuart JH; Bauman, Adrian E; Oja, Pekka (4 November 2019). "Is running associated with a lower risk of all-cause, cardiovascular and cancer mortality, and is the more the better? A systematic review and meta-analysis". British Journal of Sports Medicine: bjsports–2018–100493. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2018-100493. PMID 31685526.

- "Born To Run – Humans can outrun nearly every other animal on the planet over long distances". Discover Magazine. 2006. p. 3.

- "KLN PASS User Login".

- Alpha, Rob (2015). What Is Sport: A Controversial Essay About Why Humans Play Sports. BookBaby. ISBN 9781483555232.

- "History of Running". Health and Fitness History. 23 November 2018. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- Soviet Sport: The Success Story. p. 49, V. Gerlitsyn, 1987

- "The Evolution of Human Running: Training & Racing". runtheplanet.com. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- Ingfei Chen (May 2006). "Born To Run". Discover. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- Louis Liebenberg (December 2006). "Persistence Hunting by Modern Hunter‐Gatherers". Current Anthropology. Current Anthropology & The University of Chicago Press. 47 (6): 1017–1026. doi:10.1086/508695. JSTOR 10.1086/508695.

- Edward Seldon Sears (22 December 2008). Running Through the Ages. McFarland, 2001. ISBN 9780786450770. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- David R. Carrier, A. K. Kapoor, Tasuku Kimura, Martin K. Nickels, Satwanti, Eugenie C. Scott, Joseph K. So and Erik Trinkaus (1984). "The Energetic Paradox of Human Running and Hominid Evolution and Comments and Reply". Current Anthropology. The University of Chicago Press. 25 (4): 483–495. doi:10.1086/203165. JSTOR 2742907.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Alan Walker; Richard Leakey (16 July 1996). The Nariokotome Homo Erectus Skeleton. Springer, 1993. p. 414. ISBN 9783540563013. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- Spivey, Nigel (2006). The Ancient Olympics. ISBN 978-0-19-280604-8.

- Plato (translated by B.Jowett) - Cratylus MIT [Retrieved 2015-3-28]

- Anderson, T (1996). "Biomechanics and Running Economy". Sports Medicine. 22 (2): 76–89. doi:10.2165/00007256-199622020-00003. PMID 8857704.

- Nicola, T. L.; Jewison, D. J. (2012). "The Anatomy and Biomechanics of Running". Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine. 31 (2): 187–201. doi:10.1016/j.csm.2011.10.001. PMID 22341011.

- Novacheck, T.F. (1998). "The biomechanics of running". Gait & Posture. 7 (1): 77–95. doi:10.1016/s0966-6362(97)00038-6. PMID 10200378.

- Schache, A.G. (1999). "The coordinated movement of the lumbo-pelvic-hip complex during running: a literature review". Gait & Posture. 10 (1): 30–47. doi:10.1016/s0966-6362(99)00025-9. PMID 10469939.

- Daoud, A.I. (2012). "Foot Strike and Injury Rates in Endurance Runners: a retrospective study". Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 44 (7): 1325–1334. doi:10.1249/mss.0b013e3182465115. PMID 22217561.

- Larson, P (2011). "Foot strike patterns of recreational and sub-elite runners in a long-distance road race". Journal of Sports Sciences. 29 (15): 1665–1673. doi:10.1080/02640414.2011.610347. PMID 22092253.

- Smeathers, J.E. (1989). "Transient Vibrations Caused by Heel Strike". Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part H: Journal of Engineering in Medicine. 203 (4): 181–186. doi:10.1243/PIME_PROC_1989_203_036_01. PMID 2701953.

- Davis, G.J. (1980). "Mechanisms of Selected Knee Injuries". Journal of the American Physical Therapy Association. 60: 1590–1595.

- Hammer, S.R. (2010). "Muscle contributions to propulsion and support during running". Journal of Biomechanics. 43 (14): 2709–2716. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.06.025. PMC 2973845. PMID 20691972.

- Ardigo, L.P. (2008). "Metabolic and mechanical aspects of foot landing type, forefoot and rearfoot strike, in human running". Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 155 (1): 17–22. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1716.1995.tb09943.x. PMID 8553873.

- Bergmann, G. (2000). "Influence of shoes and heel strike on the loading of the hip joint". Journal of Biomechanics. 28 (7): 817–827. doi:10.1016/0021-9290(94)00129-r. PMID 7657680.

- Lieberman, D. (2010). "Foot strike patterns and collision forces in habitually barefoot versus shod runners". Nature. 463 (7280): 531–535. Bibcode:2010Natur.463..531L. doi:10.1038/nature08723. PMID 20111000.

- Williams, D.S. (2000). "Lower Extremity Mechanics in Runners with a Converted Forefoot Strike Pattern". Journal of Applied Biomechanics. 16 (2): 210–218. doi:10.1123/jab.16.2.210.

- Kubo, K. (2000). "Elastic properties of muscle-tendon complex in long-distance runners". European Journal of Applied Physiology. 81 (3): 181–187. doi:10.1007/s004210050028. PMID 10638375.

- Magness, S. (4 August 2010). "How to Run: Running with proper biomechanics". Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- Thys, H. (1975). "The role played by elasticity in an exercise involving movements of small amplitude". European Journal of Physiology. 354 (3): 281–286. doi:10.1007/bf00584651. PMID 1167681.

- Cavanagh, P.R. (1990). Biomechanics of Distance Running. Champaign, I.L: Human Kinetics Books.

- Verdini, F. (2005). "Identification and characterization of heel strike transient". Gait & Posture. 24 (1): 77–84. doi:10.1016/j.gaitpost.2005.07.008. PMID 16263287.

- Walter, N.E. (1977). "Stress fractures in young athletes". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 5 (4): 165–170. doi:10.1177/036354657700500405. PMID 883588.

- Perl, D.P (2012). "Effects of Footwear and Strike Type of Running Economy". Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 44 (7): 1335–1343. doi:10.1249/mss.0b013e318247989e. PMID 22217565.

- Hasegawa, H. (2007). "Foot Strike Patterns of Runners at the 15-km Point During Elite-Level Half Marathon". Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 21 (3): 888–893. doi:10.1519/00124278-200708000-00040.

- Larson, P. (2011). "Foot strike patterns of recreational and sub-elite runners in a long-distance road race". Journal of Sports Sciences. 29 (15): 1665–1673. doi:10.1080/02640414.2011.610347. PMID 22092253.

- Pink, M. (1994). "Lower Extremity Range of Motion in the Recreational Sport Runner". American Journal of Sports Medicine. 22 (4): 541–549. doi:10.1177/036354659402200418. PMID 7943522.

- Weyand, P.G. (2010). "Faster top running speeds are achieved with greater ground forces not more rapid leg movements". Journal of Applied Physiology. 89 (5): 1991–1999. doi:10.1152/jappl.2000.89.5.1991. PMID 11053354.

- Mercer, J.A. (2003). "Individual Effects of Stride Length and Frequency on Shock Attenuation during Running". Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 35 (2): 307–313. doi:10.1249/01.mss.0000048837.81430.e7. PMID 12569221.

- Stergiou, N. (2003). "Subtalara and knee joint interaction during running at various stride lengths". Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness. 43 (3): 319–326.

- Mercer, J.A. (2002). "Relationship between shock attenuation and stride length during running at different velocities". European Journal of Applied Physiology. 87 (4–5): 403–408. doi:10.1007/s00421-002-0646-9. PMID 12172880.

- Leskinen, A. (2009). "Comparison of running kinematics between elite and national-standard 1500-m runners". Sports Biomechanics. 8 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1080/14763140802632382. PMID 19391490.

- Lafortune, M.A. (2006). "Dominant role of interface over knee angle for cushioning impact loading and regulating initial leg stiffness". Journal of Biomechanics. 29 (12): 1523–1529. doi:10.1016/s0021-9290(96)80003-0.

- Skoff, B. (2004). "Kinematic analysis of Jolanda Ceplak's running technique". New Studies in Athletics. 19 (1): 23–31.

- Skoff, B (2004). "Kinematic analysis of Jolanda Ceplak's running technique". New Studies in Athletics. 19 (1): 23–31.

- Michael Yessis (2000). Explosive Running (1st ed.). McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8092-9899-0.

- Hoffman, K. (1971). "Stature, leg length and stride frequency". Track Technique. 46: 1463–1469.

- Rompottie, K. (1972). "A study of stride length in running". International Track and Field: 249–256.

- "Revel Sports Pace Chart". revelsports.com.

- Gretchen Reynolds (4 November 2009). "Phys Ed: Why Doesn't Exercise Lead to Weight Loss?". The New York Times.

- Rob Stein (29 January 2008). "Exercise Could Slow Aging of Body, Study Suggests". The Washington Post.

- "Health - Exercise 'can reverse ageing'". bbc.co.uk.

- The science of exercise shows benefits beyond weight loss. (2019). In Harvard Health Publications (Ed.), Harvard Medical School commentaries on health. Boston, MA: Harvard Health Publications. Retrieved from http://proxy-iup.klnpa.org/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/hhphoh/the_science_of_exercise_shows_benefits_beyond_weight_loss/0?institutionId=693

- Lavie, Carl J.; Lee, Duck-Chul; Sui, Xuemei; Arena, Ross; O'Keefe, James H.; Church, Timothy S.; Milani, Richard V.; Blair, Steven N. (2015). "Effects of Running on Chronic Diseases and Cardiovascular and All-Cause Mortality". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 90 (11): 1541–1552. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.001. PMID 26362561.

- "How Many Calories Does Running Burn? | Competitor.com". 2 March 2015. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- "4 Ways Running is Best for Weight Loss". 18 July 2016. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- "How Fast Should Beginners Run?". February 2013. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- Boecker, H.; Sprenger, T.; Spilker, M. E.; Henriksen, G.; Koppenhoefer, M.; Wagner, K. J.; Valet, M.; Berthele, A.; Tolle, T. R. (2008). "The Runner's High: Opioidergic Mechanisms in the Human Brain" (PDF). Cerebral Cortex. 18 (11): 2523–2531. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhn013. PMID 18296435.

- "Health benefits of running". Free Diets.

- Barton, J.; Pretty, J. (2010). "What is the Best Dose of Nature and Green Exercise for Improving Mental Health? A Multi-Study Analysis". Environmental Science & Technology. 44 (10): 3947–3955. Bibcode:2010EnST...44.3947B. doi:10.1021/es903183r. PMID 20337470.

- van Praag H, Kempermann G, Gage FH (March 1999). "Running increases cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the adult mouse dentate gyrus". Nat. Neurosci. 2 (3): 266–270. doi:10.1038/6368. PMID 10195220.

- "Memory improved by protein released in response to running". Medical News Today.

- Alic, M. (2012). Mental health and exercise. In J. L. Longe, The Gale encyclopedia of fitness. Farmington, MI: Gale. Retrieved from http://proxy-iup.klnpa.org/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/galefit/mental_health_and_exercise/0?institutionId=693

- Nielsen, R.O (2013). "Classifying running-related injuries based upon etiology, with emphasis on volume and pace". International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy. 8 (2): 172–179.

- Parker-Pope, T (6 June 2006). "Health Journal: Is barefoot better?". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- Cortese, A (29 August 2009). "Wiggling Their Toes at the Shoe Giants". The New York Times.

- Rasmus Oestergaard Nielsen, Ida Buist, Erik Thorlund Parner, Ellen Aagaard Nohr, Henrik Sørensen, Martin Lind, Sten Rasmussen (2013). "Foot pronation is not associated with increased injury risk in novice runners wearing a neutral shoe: a 1-year prospective cohort study". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 48 (6): 440–447. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2013-092202. PMID 23766439.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "How to Prevent & Treat Chafing". 27 May 2015. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- Rothfeld, G. S., & Romaine, D. S. (2017). jogger's knee. In G. S. Rothfeld, & D. Baker, Facts on File library of health and living: The encyclopedia of men's health (2nd ed.). New , NY: Facts on File. Retrieved from http://proxy-iup.klnpa.org/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/fofmens/jogger_s_knee/0?institutionId=693

- Dupler, D., & Ferguson, D. (2016). Knee injuries. In Gale (Ed.), Gale encyclopedia of children's health: Infancy through adolescence (3rd ed.). Farmington, MI: Gale. Retrieved from http://proxy-iup.klnpa.org/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/galegchita/knee_injuries/0?institutionId=693

- Newton, D. E. (2012). Running. In J. L. Longe, The Gale encyclopedia of fitness. Farmington, MI: Gale. Retrieved from http://proxy-iup.klnpa.org/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/galefit/running/0?institutionId=693

- shinsplints. (2017). In G. S. Rothfeld, & D. Baker, Facts on File library of health and living: The encyclopedia of men's health (2nd ed.). New , NY: Facts on File. Retrieved from http://proxy-iup.klnpa.org/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/fofmens/shinsplints/0?institutionId=693

- Shin splints. (2017). In Harvard Medical School (Ed.), Health reference series: Harvard Medical School health topics A-Z. Boston, MA: Harvard Health Publications. Retrieved from http://proxy-iup.klnpa.org/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/hhphealth/shin_splints/0?institutionId=693

- "Health Benefits of Jogging and Running". MotleyHealth.

- USA Track & Field (2003). "Long Distance Running – State of the Sport."

- IAAF (International Association of Athletics Federations) Biomechanical Research Project: Berlin 2009. Archived 14 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Instone, Stephen (15 November 2009). The Olympics: Ancient versus Modern. BBC. Retrieved 23 March 2010.

- 100 m – Introduction. IAAF. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- 200 m Introduction. IAAF. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- 400 m Introduction. IAAF. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- 100 m – For the Expert. IAAF. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- 200 m For the Expert. IAAF. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- Superb Bolt storms to 150m record . BBC Sport (17 May 2009). Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- Tucker, Ross (26 June 2008). Who is the fastest man in the world? Archived 23 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine. The Science of Sport. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- Middle-distance running. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- 800 m – Introduction. IAAF. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- 1500 m – Introduction. IAAF. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

External links

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.