Computational physics

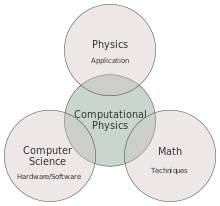

Computational physics is the study and implementation of numerical analysis to solve problems in physics for which a quantitative theory already exists.[1] Historically, computational physics was the first application of modern computers in science, and is now a subset of computational science.

| Computational physics |

|---|

|

|

Mechanics · Electromagnetics · Thermodynamics · Simulation |

|

Particle |

It is sometimes regarded as a subdiscipline (or offshoot) of theoretical physics, but others consider it an intermediate branch between theoretical and experimental physics - an area of study which supplements both theory and experiment.[2]

Overview

In physics, different theories based on mathematical models provide very precise predictions on how systems behave. Unfortunately, it is often the case that solving the mathematical model for a particular system in order to produce a useful prediction is not feasible. This can occur, for instance, when the solution does not have a closed-form expression, or is too complicated. In such cases, numerical approximations are required. Computational physics is the subject that deals with these numerical approximations: the approximation of the solution is written as a finite (and typically large) number of simple mathematical operations (algorithm), and a computer is used to perform these operations and compute an approximated solution and respective error.[1]

Status in physics

There is a debate about the status of computation within the scientific method.[4]

Sometimes it is regarded as more akin to theoretical physics; some others regard computer simulation as "computer experiments",[4] yet still others consider it an intermediate or different branch between theoretical and experimental physics, a third way that supplements theory and experiment. While computers can be used in experiments for the measurement and recording (and storage) of data, this clearly does not constitute a computational approach.

Challenges in computational physics

Computational physics problems are in general very difficult to solve exactly. This is due to several (mathematical) reasons: lack of algebraic and/or analytic solubility, complexity, and chaos.

For example, - even apparently simple problems, such as calculating the wavefunction of an electron orbiting an atom in a strong electric field (Stark effect), may require great effort to formulate a practical algorithm (if one can be found); other cruder or brute-force techniques, such as graphical methods or root finding, may be required. On the more advanced side, mathematical perturbation theory is also sometimes used (a working is shown for this particular example here).

In addition, the computational cost and computational complexity for many-body problems (and their classical counterparts) tend to grow quickly. A macroscopic system typically has a size of the order of constituent particles, so it is somewhat of a problem. Solving quantum mechanical problems is generally of exponential order in the size of the system[5] and for classical N-body it is of order N-squared.

Finally, many physical systems are inherently nonlinear at best, and at worst chaotic: this means it can be difficult to ensure any numerical errors do not grow to the point of rendering the 'solution' useless.[6]

Methods and algorithms

Because computational physics uses a broad class of problems, it is generally divided amongst the different mathematical problems it numerically solves, or the methods it applies. Between them, one can consider:

- root finding (using e.g. Newton-Raphson method)

- system of linear equations (using e.g. LU decomposition)

- ordinary differential equations (using e.g. Runge–Kutta methods)

- integration (using e.g. Romberg method and Monte Carlo integration)

- partial differential equations (using e.g. finite difference method and relaxation method)

- matrix eigenvalue problem (using e.g. Jacobi eigenvalue algorithm and power iteration)

All these methods (and several others) are used to calculate physical properties of the modeled systems.

Computational physics also borrows a number of ideas from computational chemistry - for example, the density functional theory used by computational solid state physicists to calculate properties of solids is basically the same as that used by chemists to calculate the properties of molecules.

Furthermore, computational physics encompasses the tuning of the software/hardware structure to solve the problems (as the problems usually can be very large, in processing power need or in memory requests).

Divisions

It is possible to find a corresponding computational branch for every major field in physics, for example computational mechanics and computational electrodynamics. Computational mechanics consists of computational fluid dynamics (CFD), computational solid mechanics and computational contact mechanics. One subfield at the confluence between CFD and electromagnetic modelling is computational magnetohydrodynamics. The quantum many-body problem leads naturally to the large and rapidly growing field of computational chemistry.

Computational solid state physics is a very important division of computational physics dealing directly with material science.

A field related to computational condensed matter is computational statistical mechanics, which deals with the simulation of models and theories (such as percolation and spin models) that are difficult to solve otherwise. Computational statistical physics makes heavy use of Monte Carlo-like methods. More broadly, (particularly through the use of agent based modeling and cellular automata) it also concerns itself with (and finds application in, through the use of its techniques) in the social sciences, network theory, and mathematical models for the propagation of disease (most notably, the SIR Model) and the spread of forest fires.

On the more esoteric side, numerical relativity is a (relatively) new field interested in finding numerical solutions to the field equations of general (and special) relativity, and computational particle physics deals with problems motivated by particle physics.

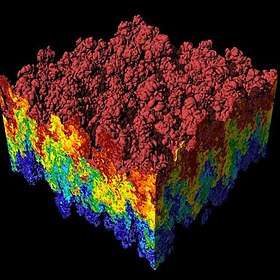

Computational astrophysics is the application of these techniques and methods to astrophysical problems and phenomena.

Computational biophysics is a branch of biophysics and computational biology itself, applying methods of computer science and physics to large complex biological problems.

Applications

Due to the broad class of problems computational physics deals, it is an essential component of modern research in different areas of physics, namely: accelerator physics, astrophysics, fluid mechanics (computational fluid dynamics), lattice field theory/lattice gauge theory (especially lattice quantum chromodynamics), plasma physics (see plasma modeling), simulating physical systems (using e.g. molecular dynamics), nuclear engineering computer codes, protein structure prediction, weather prediction, solid state physics, soft condensed matter physics, hypervelocity impact physics etc.

Computational solid state physics, for example, uses density functional theory to calculate properties of solids, a method similar to that used by chemists to study molecules. Other quantities of interest in solid state physics, such as the electronic band structure, magnetic properties and charge densities can be calculated by this and several methods, including the Luttinger-Kohn/k.p method and ab-initio methods.

See also

- Advanced Simulation Library

- CECAM - Centre européen de calcul atomique et moléculaire

- Division of Computational Physics (DCOMP) of the American Physical Society

- Important publications in computational physics

- Mathematical and theoretical physics

- Open Source Physics, computational physics libraries and pedagogical tools

- Timeline of computational physics

- Car–Parrinello molecular dynamics

References

- Thijssen, Jos (2007). Computational Physics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521833462.

- Landau, Rubin H.; Páez, Manuel J.; Bordeianu, Cristian C. (2015). Computational Physics: Problem Solving with Python. John Wiley & Sons.

- Landau, Rubin H.; Paez, Jose; Bordeianu, Cristian C. (2011). A survey of computational physics: introductory computational science. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691131375.

- A molecular dynamics primer Archived 2015-01-11 at the Wayback Machine, Furio Ercolessi, University of Udine, Italy. Article PDF Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine.

- Feynman, Richard P. (1982). "Simulating physics with computers". International Journal of Theoretical Physics. 21 (6–7): 467–488. Bibcode:1982IJTP...21..467F. doi:10.1007/bf02650179. ISSN 0020-7748. Article PDF

- Sauer, Tim; Grebogi, Celso; Yorke, James A (1997). "How Long Do Numerical Chaotic Solutions Remain Valid?". Physical Review Letters. 79 (1): 59–62. Bibcode:1997PhRvL..79...59S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.79.59. S2CID 102493915.

Further reading

- A.K. Hartmann, Practical Guide to Computer Simulations, World Scientific (2009)

- International Journal of Modern Physics C (IJMPC): Physics and Computers, World Scientific

- Steven E. Koonin, Computational Physics, Addison-Wesley (1986)

- T. Pang, An Introduction to Computational Physics, Cambridge University Press (2010)

- B. Stickler, E. Schachinger, Basic concepts in computational physics, Springer Verlag (2013). ISBN 9783319024349.

- E. Winsberg, Science in the Age of Computer Simulation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Computational physics. |