Beit She'an

Beit She'an (Hebrew: בֵּית שְׁאָן ![]()

![]()

Beit She'an

| |

|---|---|

| Hebrew transcription(s) | |

| • ISO 259 | Beit Šˀan |

| • Translit. | Bet Šəʼan |

| • Also spelled | Bet She'an (official) Beth Shean (unofficial) |

Beit She'an Hostel & Guest House | |

| |

Beit She'an  Beit She'an | |

| Coordinates: 32°30′N 35°30′E | |

| Country | |

| District | Northern |

| Founded | 6th-5th millennia BCE (Earliest settlement) Bronze Age (Canaanite city) |

| Government | |

| • Type | City |

| • Mayor | Jackie Levy |

| Area | |

| • Total | 7,330 dunams (7.33 km2 or 2.83 sq mi) |

| Population (2018)[1] | |

| • Total | 18,227 |

| • Density | 2,500/km2 (6,400/sq mi) |

| Name meaning | House of Tranquillity[2] |

| Website | http://www.bet-shean.org.il |

._Beisan_mound_LOC_matpc.17062.jpg)

The ancient city ruins are now protected within the Beit She'an National Park.

Geography

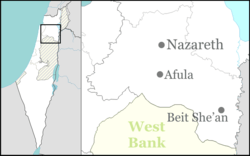

Beit She'an's location has always been strategically significant, due to its position at the junction of the Jordan River Valley and the Jezreel Valley, essentially controlling access from Jordan and the inland to the coast, as well as from Jerusalem and Jericho to the Galilee.

Beit She'an is situated on Highway 90, the north–south road which runs the length of Israel. The city stretches over an area of 7 square kilometers with a substantial national park in the north of the city. Beit She'an has a population of 20,000.[5]

Today the town is under the administration of the Emek HaMa'ayanot Regional Council.

History

Prehistory (Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods)

In 1933, archaeologist G.M. FitzGerald, under the auspices of the University of Pennsylvania Museum, carried out a "deep cut" on Tell el-Hisn ("castle hill"), the large tell, or mound, of Beth She'an, in order to determine the earliest occupation of the site. His results suggest that settlement began in the Late Neolithic or Early Chalcolithic periods (sixth to fifth millennia BCE.)[6] Occupation continued intermittently throughout the Late Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods, with a likely gap during the Late Chalcolithic period.[7]

Bronze Age

Settlement seems to have resumed at the beginning of the Early Bronze Age I (3200–3000) and continues throughout this period, is then missing during Early Bronze Age II, and then resumes in the Early Bronze Age III.[7]

A large cemetery on the northern mound was in use from the Bronze Age to Byzantine times.[8] Canaanite graves dating from 2000 to 1600 BCE were discovered there in 1926.[9]

Egyptian period

After the Egyptian conquest of Beit She'an by Pharaoh Thutmose III in the 15th century BCE, as recorded in an inscription at Karnak,[10] the small town on the summit of the mound became the center of the Egyptian administration of the region.[11] The Egyptian newcomers changed the organization of the town and left a great deal of material culture behind. A large Canaanite temple (39 meters in length) excavated by the University of Pennsylvania Museum (Penn Museum) may date from about the same period as Thutmose III's conquest, though the Hebrew University excavations suggest that it dates to a later period.[12] Artifacts of potential cultic significance were found around the temple. Based on a stele found in the temple, inscribed with Egyptian hieroglyphs, the temple was dedicated to the god Mekal.[13] The Hebrew University excavations determined that this temple was built on the site of an earlier one.[14]

%2C_Israel_(25860307202).jpg)

One of the most important finds near the temple is the Lion and Lioness (or a dog[15]) stela, currently in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, which depicts the two playing.[16]

During the three hundred years of Egyptian rule (18th to 20th Dynasty), the population of Beit She'an appears to have been primarily Egyptian administrative officials and military personnel. The town was completely rebuilt, following a new layout, during the 19th dynasty.[17] The Penn Museum excavations uncovered two important stelae from the period of Seti I and a monument of Rameses II.[18] One of those steles is particularly interesting because, according to Albright,[19] it testifies to the presence of a Hebrew population: the Apirus, which Seti I protected from an Asiatic tribe. Pottery was produced locally, but some was made to mimic Egyptian forms.[20] Other Canaanite goods existed alongside Egyptian imports, or locally made Egyptian-style objects.[21] The 20th Dynasty saw the construction of large administrative buildings in Beit She'an, including "Building 1500", a small palace for the Egyptian governor.[22] During the 20th Dynasty, invasions of the "Sea Peoples" upset Egypt's control over the Eastern Mediterranean. Though the exact circumstances are unclear, the entire site of Beit She'an was destroyed by fire around 1150 BCE. The Egyptians did not attempt to rebuild their administrative center and finally lost control of the region.

Iron Age

According to the Hebrew Bible, around 1000 BC the town became part of the larger Israelite kingdom. 1 Kings 4:12 refers to Beit She'an as part of the kingdom of Solomon, though the historical accuracy of this list is debated.[23] An Iron Age I (1200-1000 BC) Canaanite city was constructed on the site of the Egyptian center shortly after its destruction.[24]

The Assyrian conquest of the northern kingdom of Israel under Tiglath-Pileser III (732 BC) brought about the destruction of Beit She'an by fire.[20]

Minimal reoccupation occurred until the Hellenistic period.[20]

Biblical narrative

According to the Hebrew Bible, around 1100 BCE during a battle against King Saul at nearby Mount Gilboa in 1004 BC, the Philistines prevailed and Saul together with three of his sons, Jonathan, Abinadab and Malchishua, died in battle (1 Samuel 31; 1 Chronicles 10). 1 Samuel 31:10 states that "the victorious Philistines hung the body of King Saul on the walls of Beit She'an". No archeological evidence was found of Philistines occupation, but it is possible the force only passed there.[15]

Hellenistic period

The Hellenistic period saw the reoccupation of the site of Beit She'an under the new name "Scythopolis" (Ancient Greek: Σκυθόπολις), possibly named after the Scythian mercenaries who settled there as veterans. Little is known about the Hellenistic city, but during the 3rd century BCE a large temple was constructed on the tell.[25] It is unknown which deity was worshipped there, but the temple continued to be used during Roman times. Graves dating from the Hellenistic period are simple, singular rock-cut tombs.[26] From 301 to 198 BCE the area was under the control of the Ptolemies, and Beit She'an is mentioned in 3rd–2nd century BCE written sources describing the Syrian Wars between the Ptolemid and Seleucid dynasties. In 198 BCE the Seleucids finally conquered the region.

Roman period

In 63 BCE, Pompey made Judea a part of the Roman empire. Beit She'an was refounded and rebuilt by Gabinius.[27] The town center shifted from the summit of the mound, or tell, to its slopes. Scythopolis prospered and became the leading city of the Decapolis, the only one west of the Jordan River.[28]

The city flourished under the "Pax Romana", as evidenced by high-level urban planning and extensive construction, including the best preserved Roman theatre of ancient Samaria, as well as a hippodrome, a cardo and other trademarks of the Roman influence. Mount Gilboa, 7 km (4 mi) away, provided dark basalt blocks, as well as water (via an aqueduct) to the town. Beit She'an is said to have sided with the Romans during the Jewish uprising of 66 CE.[27] Excavations have focused less on the Roman period ruins, so not much is known about this period. The Penn. University Museum excavation of the northern cemetery, however, did uncover significant finds. The Roman period tombs are of the loculus type: a rectangular rock-cut spacious chamber with smaller chambers (loculi) cut into its side.[26] Bodies were placed directly in the loculi, or inside sarcophagi which were placed in the loculi. A sarcophagus with an inscription identifying its occupant in Greek as "Antiochus, the son of Phallion", may have held the cousin of Herod the Great.[26] One of the most interesting Roman grave finds was a bronze incense shovel with the handle in the form of an animal leg, or hoof, now in the University of Pennsylvania Museum.[29]

Byzantine period

Copious archaeological remains were found dating to the Byzantine period (330–636 CE) and were excavated by the University of Pennsylvania Museum from 1921–23. A rotunda church was constructed on top of the Tell and the entire city was enclosed in a wall.[31] Textual sources mention several other churches in the town.[31] Beit She'an was primarily Christian, as attested to by the large number of churches, but evidence of Jewish habitation and a Samaritan synagogue indicate established communities of these minorities. The pagan temple in the city centre was destroyed, but the nymphaeum and Roman baths were restored. Many of the buildings of Scythopolis were damaged in the Galilee earthquake of 363, and in 409 it became the capital of the northern district, Palaestina Secunda.[32] As such, Scythopolis (v.) also became the Metropolitan archdiocese of the province.

Dedicatory inscriptions indicate a preference for donations to religious buildings, and many colourful mosaics, such as that featuring the zodiac in the Monastery of Lady Mary, or the one picturing a menorah and shalom in the House of Leontius' Jewish synagogue, were preserved. A Samaritan synagogue's mosaic was unique in abstaining from human or animal images, instead utilising floral and geometrical motifs. Elaborate decorations were also found in the settlement's many luxurious villas, and in the 6th century especially, the city reached its maximum size of 40,000 and spread beyond its period city walls.[32]

The Byzantine period portion of the northern cemetery was excavated in 1926. The tombs from this period consisted of small rock-cut halls with vaulted graves on three sides.[33] A great variety of objects were found in the tombs, including terracotta figurines possibly depicting the Virgin and Child, many terracotta lamps, glass mirrors, bells, tools, knives, finger rings, iron keys, glass beads, bone hairpins, and many other items.[33]

Important Christian personalities who lived or passed through Byzantine Scythopolis are St Procopius of Scythopolis (died July 7, 303 AD), Cyril of Scythopolis (ca. 525–559), St Epiphanius of Salamis (c. 310/320 – 403) and Joseph of Tiberias (c. 285 – c. 356) who met there around the year 355.

Early Muslim period

In 634, Byzantine forces were defeated by the Muslim army of Caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab and the city reverted to its Semitic name, being named Baysan in Arabic. The day of victory came to be known in Arabic as Yawm Baysan or "the day of Baysan."[2] The city was not damaged and the newly arrived Muslims lived together with its Christian population until the 8th century, but the city declined during this period. Structures were built in the streets themselves, narrowing them to mere alleyways, and makeshift shops were opened among the colonnades. The city reached a low point by the 8th century, witnessed by the removal of marble for producing lime, the blocking off of the main street, and the conversion of a main plaza into a cemetery.[34] However, some recently discovered counter-evidence may be offered to this picture of decline. In common with state-directed building work carried out in other towns and cities in the region during the 720s,[35] Baysan's commercial infrastructure was refurbished: its main colonnaded market street, once thought to date to the sixth century, is now known—on the basis of a mosaic inscription—to be a redesign dating from the time of the Umayyad caliph Hisham (r. 724–43).[36] Abu Ubayd al-Andalusi noted that the wine produced there was delicious.[2]

On January 18, 749, Umayyad Baysan was completely devastated by a catastrophic earthquake. A few residential neighborhoods grew up on the ruins, probably established by the survivors, but the city never recovered its magnificence. The city center moved to the southern hill where later the Crusaders built their castle.[37]

Jerusalemite historian al-Muqaddasi visited Baysan in 985, during Abbasid rule and wrote that it was "on the river, with plentiful palm trees, and water, though somewhat heavy (brackish.)" He further noted that Baysan was notable for its indigo, rice, dates and grape syrup known as dibs.[38] The town formed one of the districts (kurah) of Jund al-Urdunn during this period.[39] Its principal mosque was situated in the center of its marketplace.[40]

Crusader period

In the Crusader period, the Lordship of Bessan was occupied by Tancred in 1099; it was never part of the Principality of Galilee, despite its location, but became a royal domain of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem in 1101, probably until around 1120. According to the Lignages d'Outremer, the first Crusader lord of Bessan once it became part of the Kingdom of Jerusalem was Adam, a younger son of Robert III de Béthune, peer of Flanders and head of the House of Bethune. His descendants were known by the family name de Bessan.[41]

It occasionally passed back under royal control until new lords were created, becoming part of the Belvoir fiefdom.[42]

A small Crusader fortress surrounded by a moat was built in the area southeast of the Roman theatre, where the diminished town had relocated after the 749 earthquake.[37] The fortress was destroyed by Saladin in 1183.[43]

During the 1260 Battle of Ain Jalut, retreating Mongol forces passed in the vicinity but did not enter the town itself.

Mamluk period

Under Mamluk rule, Beit She'an was the principal town in the district of Damascus and a relay station for the postal service between Damascus and Cairo. It was also the capital of sugar cane processing for the region. Jisr al-Maqtu'a, "the truncated/cut-off bridge", a bridge consisting of a single arch spanning 25 feet and hung 50 feet above a stream, was built during that period.[44]

Ottoman period

During this period the inhabitants of Beit She'an were mainly Muslim. There were however some Jews. For example, the 14th century topographer Ishtori Haparchi settled there and completed his work Kaftor Vaferach in 1322, the first Hebrew book on the geography of Palestine.[45]

During the 400 years of Ottoman rule, Baysan lost its regional importance. During the reign of Sultan Abdul Hamid II when the Jezreel Valley railway, which was part of the Haifa-Damascus extension of the Hejaz railway was constructed, a limited revival took place. The local peasant population was largely impoverished by the Ottoman feudal land system which leased tracts of land to tenants and collected taxes from them for their use.[2]

The Swiss–German traveler Johann Ludwig Burckhardt described Beisan in 1812 as "a village with 70 to 80 houses, whose residents are in a miserable state." In the early 1900s, though still a small and obscure village, Beisan was known for its plentiful water supply, fertile soil, and its production of olives, grapes, figs, almonds, apricots, and apples.[2]

British Mandate period

Under the Mandate, the city was the center of the District of Baysan. According to a census conducted in 1922 by the British Mandate authorities, Beit She'an (Baisan) had a population of 1,941, consisting of 1,687 Muslims, 41 Jews and 213 Christians.[46]

In 1934, Lawrence of Arabia noted that "Bisan is now a purely Arab village," where "very fine views of the river can be had from the housetops." He further noted that "many nomad and Bedouin encampments, distinguished by their black tents, were scattered about the riverine plain, their flocks and herds grazing round them."[2] Beisan was home to a mainly Mizrahi Jewish community of 95 until 1936, when the 1936–1939 Arab revolt saw Beisan serve as a center of Arab attacks on Jews in Palestine.[45][47][48] In 1938, after learning of the murder of his close friend and Jewish leader Haim Sturmann, Orde Wingate led his men on an offensive in the Arab section of Baysan, the rebels’ suspected base.[49]

According to population surveys conducted in British Mandate Palestine, Beisan consisted of 5,080 Muslim Arabs out of a population of 5,540 (92% of the population), with the remainder being listed as Christians.[50] In 1945, the surrounding District of Baysan consisted of 16,660 Muslims (67%), 7,590 Jews (30%), and 680 Christians (3%); and Arabs owned 44% of land, Jews owned 34%, and 22% constituted public lands. The 1947 UN Partition Plan allocated Beisan and most of its district to the proposed Jewish state.[2][51][52]

Jewish forces and local Bedouins first clashed during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War in February and March 1948, part of Operation Gideon,[2] which Walid Khalidi argues was part of a wider Plan Dalet.[53] Joseph Weitz, a leading Yishuv figure, wrote in his diary on May 4, 1948 that, "The Beit Shean Valley is the gate for our state in the Galilee...[I]ts clearing is the need of the hour."[2]

Beisan, then an Arab village, fell to the Jewish militias three days before the end of the Mandate.

State of Israel

After Israel's Declaration of Independence in May 1948, during intense shelling by Syrian border units, followed by the recapture of the valley by the Haganah, the Arab inhabitants fled across the Jordan River.[54] The property and buildings abandoned after the conflict were then held by the State of Israel.[2] Most Arab Christians relocated to Nazareth. A ma'abarah (refugee camp) inhabited mainly by North African Jewish refugees[55] was erected in Beit She'an, and it later became a development town.

From 1969, Beit She'an was a target for Katyusha rockets and mortar attacks from Jordan.[56] In the 1974 Beit She'an attack, militants of the Popular Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine, took over an apartment building and murdered a family of four.[47]

In 1999, Beit She'an was incorporated as a city.[57] Geographically, it lies in the middle of the Beit She'an Valley Regional Council.[58]

Beit She'an was the hometown and political power base of David Levy, a prominent figure in Israeli politics.

During the Second Intifada, in the 2002 Beit She'an attack, six Israelis were killed and over 30 were injured by two Palestinian militants, who opened fire and threw grenades at a polling station in the center of Bet She'an where party members were voting in the Likud primary.

Archaeology and tourism

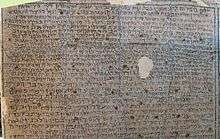

The University of Pennsylvania carried out excavations of ancient Beit She'an in 1921–1933. Relics from the Egyptian period were discovered, most of them now exhibited in the Rockefeller Museum in Jerusalem. Some are in the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia.[59] Excavations at the site were resumed by the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in 1983 and then again from 1989 to 1996 under the direction of Amihai Mazar.[60] The excavations have revealed no less than 18 successive ancient towns.[61][62] Ancient Beit She'an, one of the most spectacular Roman and Byzantine sites in Israel, is a major tourist attraction.[63] The seventh century Mosaic of Rehob was discovered by farmers of Kibbutz Ein HaNetziv. Part of a mosaic floor, it contains details of Jewish religious laws concerning tithes and the Sabbatical Year.[64]

Earthquakes

Beit She'an is located above the Dead Sea Transform (a fault system that forms the transform boundary between the African Plate to the west and the Arabian Plate to the east) and is one of the cities in Israel most at risk to earthquakes (along with Safed, Tiberias, Kiryat Shmona and Eilat).[65] Historically, the city was destroyed in the Golan earthquake of 749.

Demographics

According to the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), the population of the municipality was 18,227 at the end of 2018.[1] In 2005, the ethnic makeup of the city was 99.5% Jewish and other non-Arab (97.3% Jewish), with no significant Arab population. See Population groups in Israel. The population breakdown by gender was 8,200 males and 8,100 females.[66]

The age distribution was as follows:

| Age | 0–4 | 5–9 | 10–14 | 15–19 | 20–29 | 30–44 | 45–59 | 60–64 | 65–74 | 75+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage | 9.9 | 9.4 | 9.4 | 9.4 | 17.6 | 17.7 | 16.7 | 2.7 | 4.4 | 2.8 |

| Source: Israel Central Bureau of Statistics[66] | ||||||||||

Economy

Beit She'an is a center of cotton-growing, and many of residents are employed in the cotton fields of the surrounding kibbutzim. Other local industries include a textile mill and clothing factory.[45]

When the ancient city of Beit She'an was opened to the public in the 1990s and turned into a national park, tourism became a major sector of the economy.[67]

Education

According to CBS, there are 16 schools and 3,809 students in the city. They are spread out as 10 elementary schools and 2,008 elementary school students, and 10 high schools and 1,801 high school students. 56.2% of 12th grade students were entitled to a matriculation certificate in 2001.

Transportation

Beit She'an had a railway station that opened in 1904 on the Jezreel Valley railway which was an extension of the Hejaz railway. This station closed together with the rest of the Jezreel Valley railway in 1948. In 2011–2016 the valley railway was rebuilt and the new Beit She'an Railway Station, located at the same site as the historical station was opened. Passenger service offered at the station connects the city to Afula, Haifa and destinations in between. In addition to passenger service, the station also includes a freight rail terminal.

Sports

The local football club, Hapoel Beit She'an spent several seasons in the top division in the 1990s, but folded in 2006 after several relegations. Maccabi Beit She'an currently plays in Liga Bet.

Notable residents

Historic images

Historic railway station, 1930s

Historic railway station, 1930s Beit She'an after conquest, 1948

Beit She'an after conquest, 1948 Ottoman Saray building used by Yiftach Brigade as company barracks. 1948

Ottoman Saray building used by Yiftach Brigade as company barracks. 1948 Abandoned property, 1948

Abandoned property, 1948 Beit She'an (Beisan) Police Station, 1948

Beit She'an (Beisan) Police Station, 1948 Beit She'an, 1948

Beit She'an, 1948

See also

- List of Arab towns and villages depopulated during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War

- Vassals of the Kingdom of Jerusalem

- Sheikh Hussein Bridge

References

- "Population in the Localities 2018" (XLS). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. 25 August 2019. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- Shahin, Mariam (2005). Palestine: A Guide. Interlink Books. pp. 159–165. ISBN 1-56656-557-X.

- Was King Saul Impaled on the Wall of Beth Shean?

- Beit She'an, Archaeology in Israel

- Nefesh B'Nefesh Profiles: Beit She'an

- Braun, Eliot. Early Beth Shean (Strata XIX-XIII): G.M. FitzGerald's Deep Cut on the Tell, p. 28

- Braun, p.61-64

- Rowe, Alan. The Topography and History of Beth Shean. Philadelphia: 1930, p. v

- Rowe, p. 2

- No. 110: bt š'ir. Mazar, Amihai. "Tel Beth-Shean: History and Archaeology." In One God, One Cult, One Nation. Ed. R.G. Kratz and H. Spieckermann. New York: 2010, P. 239

- Mazar 242

- Rowe, 10; http://www.rehov.org/project/tel_beth_shean.htm Archived 2012-02-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Rowe 11

- Mazar 247

- http://www.rehov.org/project/tel_beth_shean.htm Archived 2012-02-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Lion and Lioness playing, Israel Museum

- Mazar 250

- Rowe 23–32

- Albright W. The smaller Beth-Shean stele of Sethos I (1309-1290 B. C.), Bulletin of the American schools of Oriental research, feb 1952, p. 24-32.

- "Tel Beth Shean: An Account of the Hebrew University's Excavations". Rehov.org. Archived from the original on 2012-02-06. Retrieved 2012-03-04.

- Mazar 256

- Mazar 253

- Mazar 263

- "The Beth-Shean Valley Archaeological Project". Rehov.org. Archived from the original on 2012-02-04. Retrieved 2012-03-04.

- Rowe 44

- Rowe 49

- Rowe 46

- Alexander, Etruscans and a Field Trip to Beit Shean

- Rowe 53

- Synagogue floor: Beth Shean synagogue, ay IMJ website, accessed 16 July 2019

- Rowe 50

- Rowe 45

- Rowe 52

- "Beit She'an". Jewish Virtual Library.

- A. Walmsley, "Economic Developments and the Nature of Settlement in the Towns and Countryside of Syria-Palestine, ca. 565–800", Dumbarton Oaks Papers 61 (2007), especially pp. 344–45.

- E. Khamis, "Two wall mosaic inscriptions from the Umayyad market place in Bet Shean/Baysan", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 64 (2001), pp. 159–76.

- "Israel Antiquities Authority, Death of a City". Antiquities.org.il. Archived from the original on 2013-09-15. Retrieved 2012-12-30.

- le Strange, 1890, pp. 18–19.

- le Strange, 1890, p. 30

- le Strange, 1890, p. 411

- Jerusalem Nobility, retrieved 18 June 2016

- גן לאומי בית שאן (in Hebrew). Israel National Parks Authority. Archived from the original on 2012-04-25.

- Avraham Negev and Shimon Gibson (2001). Beth Shean (city); Scythopolis. Archaeological Encyclopedia of the Holy Land. New York and London: Continuum. p. 86. ISBN 0-8264-1316-1.

- Shahin, 2005, p. 164

- "Bet She'an". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- Barron, 1923, p. 6

- Ashkenazi, Eli (2007-05-11). "The other Beit She'an". Haaretz. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- "Virtual Israel Experience:Bet She'an". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- Michael B. Oren (Winter 2001). "Orde Wingate: Friend Under Fire". Azure: Ideas for the Jewish Nation. Retrieved 2007-05-15.

- "Settled Population Of Palestine". United Nations. Archived from the original on March 19, 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-01.

- A Survey of Palestine: Prepared in December, 1945 and January, 1946 for the Information of the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry. 1. Institute for Palestine Studies. 1991. pp. 12–13. ISBN 0-88728-211-3.

- Land Ownership of Palestine—Map prepared by the government of the British Mandate of Palestine on the instructions of the UN Ad Hoc Committee on the Palestine Question (Map). United Nations. Archived from the original on 29 October 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- Khalidi, Walid (Autumn 1988). "Plan Dalet: Master Plan for the Conquest of Palestine". Journal of Palestine Studies. Journal of Palestine Studies. 18 (1): 4–33. doi:10.1525/jps.1988.18.1.00p00037. JSTOR 2537591.

- WPN Tyler, State lands and rural development in mandatory Palestine, 1920–1948, p. 79

- Maier, J. (1985). Piccola enciclopedia dell'ebraismo. Casale Monferrato (Italy): Marietti. p. 95. ISBN 88-211-8329-7.

- "Jordanian katusha, bazuka and mortar attack on Beit She'an", Maariv, 22 Jun 1969, scan source: Historical Jewish press

- הסראיה – בית שאן. 7wonders.co.il (in Hebrew). Archived from the original on 5 March 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-08.

- "Beit Shean" (PDF). Friends of the Earth Middle East (FoEME). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- Ousterhout, Robert; Boomer, Megan; Chalmers, Matthew; Fleck, Victoria; Kopta, Joseph R.; Shackelford, James; Vandewalle, Rebecca; Winnik, Arielle. "Beth Shean After Antiquity". Beth Shean After Antiquity.

- "Archaeowiki.org". www.archaeowiki.org. Archived from the original on 16 March 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- "Beth Shean (Israel)". University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- Heiser, Lauren (2000-03-10). "Beth Shean" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2004-12-28. Retrieved 2009-02-04. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Beit She'an". Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 25 March 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-08.

- The permitted villages of Sebaste in the Rehov Mosaic

- Experts Warn: Major Earthquake Could Hit Israel Any Time By Rachel Avraham, staff writer for United With Israel Date: Oct 22, 2013

- "Local Authorities in Israel 2005, Publication #1295 – Municipality Profiles — Beit She'an" (PDF) (in Hebrew). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 2008-07-05.

- "Israeli archaeologists unearthing treasures of a long lost city". The New York Times.

- "Cleveland Sister City Partnerships". Encyclopedia of Cleveland History (Case Western Reserve University). Retrieved 2019-05-27.

Bibliography

- Shahin, Mariam (2005). Palestine: A Guide. Interlink Books. pp. 159–165. ISBN 1-56656-557-X.

- Sharon, Moshe (1999). Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae, B-C. 2. Brill. ISBN 90-04-11083-6. (see p.195 ff)

- Strange, le, Guy (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Tsafrir, Yoram and Foerster, Gideon: "“Nysa-Scythopolis – A New Inscription and the Titles of the City on its Coins", The Israel Numismatic Journal. Vol. 9, 1986–7, pp. 53–58.

- Tsafrir, Yoram and Foerster, Gideon: "Bet Shean Excavation Project – 1988/1989", Excavations and Surveys in Israel 1989/1990. Volume 9. Israel Antiquities Authority. Numbers 94–95. Jerusalem 1989/1990, pp. 120–128.

- Tsafrir, Yoram and Foerster, Gideon: "From Scythopolis to Baisān: Changes in the perception of the city of Bet Shean during the Byzantine and Arab Eras", Cathedra. For the History of Eretz Israel and its Yishuv, 64. Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi. Jerusalem, July 1992 (in Hebrew).

- Tsafrir, Yoram and Foerster, Gideon: "The Dating of the 'Earthquake of the Sabbatical Year of 749 C. E.' in Palestine", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies of London. Vol. LV, Part 2. London 1992, pp. 231–235.

- Tsafrir, Yoram and Foerster, Gideon: "Urbanism at Scythopolis-Bet Shean in the Fourth to Seventh Centuries", Dumbarton Oaks Papers. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. Number Fifty-One, 1997. pp. 85–146.

Further reading

University of Pennsylvania excavations

- Braun, Eliot [2004], Early Beth Shan (Strata XIX-XIII) – G.M. FitzGerald's Deep Cut on the Tell, [University Museum Monograph 121], Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum, 2004. ISBN 1-931707-62-6

- Fisher, Clarence [1923], Beth-Shan Excavations of the University Museum Expedition, 1921–1923", Museum Journal 14 (1923), pp. 229–231.

- FitzGerald, G.M. [1931], Beth-shan Excavations 1921–23: the Arab and Byzantine Levels, Beth-shan III, University Museum: Philadelphia, 1931.

- FitzGerald, G.M. [1932], "Excavations at Beth-Shan in 1931", PEFQS 63 (1932), pp. 142–145.

- Rowe, Alan [1930], The Topography and History of Beth-Shan, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1930.

- Rowe, Alan [1940], The Four Canaanite Temples of Beth-shan, Beth-shan II:1, University Museum: Philadelphia, 1940.

- James, Frances W. & McGovern, Patrick E. [1993], The Late Bronze Egyptian Garrison at Beth Shan: a Study of Levels VII and VIII, 2 volumes, [University Museum Monograph 85], Philadelphia: University Museum, University of Pennsylvania & University of Mississippi, 1993. ISBN 0-924171-27-8

Hebrew University Jerusalem excavations

- Mazar, Amihai [2006], Excavations at Tel Beth Shean 1989–1996, Volume I: From the Late Bronze Age IIB to the Medieval Period, Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society / Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 2006.

- Mazar, A. and Mullins, Robert (eds) [2007], Excavations at Tel Beth Shean 1989–1996, Volume II: The Middle and Late Bronze Age Strata in Area R, Jerusalem: IES / HUJ, 2007.

General

- Barron, J. B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Finkelstein, Israel [1996], "The Stratigraphy and Chronology of Megiddo and Beth-Shan in the 12th–11th Centuries BCE", TA 23 (1996), pp. 170–184.

- Garfinkel, Yosef [1987], "The Early Iron Age Stratigraphy of Beth Shean Reconsidered", IEJ 37 (1987), pp. 224–228.

- Geva, Shulamit [1979], "A Reassessment of the Chronology of Beth Shean Strata V and IV", IEJ 29 (1979), pp. 6–10.

- Greenberg, Raphael [2003], "Early Bronze Age Megiddo and Beth Shean: Discontinuous Settlement in Sociopolitical Context", JMA 16.1 (2003), pp. 17–32.

- Hankey, V. [1966], "Late Mycenaean Pottery at Beth-Shan", AJA 70 (1966), pp. 169–171.

- Higginbotham, C. [1999], "The Statue of Ramses III from Beth Shean", TA 26 (1999), pp. 225–232.

- Horowitz, Wayne [1994], "Trouble in Canaan: A Letter of the el-Amarna Period on a Clay Cylinder from Beth Shean", Qadmoniot 27 (1994), pp. 84–86 (Hebrew).

- Horowitz, Wayne [1996], "An Inscribed Clay Cylinder from Amarna Age Beth Shean", IEJ 46 (1996), pp. 208–218.

- McGovern, Patrick E. [1987], “Silicate Industries of Late Bronze-Early Iron Age Palestine: Technological Interaction between New Kingdom Egypt and the Levant", in Bimson, M. & Freestone, LC. (eds), Early Vitreous Materials, [British Museum Occasional Papers 56], London: British Museum Press, 1987, pp. 91–114.

- McGovern, Patrick E. [1989], "Cross-Cultural Craft Interaction: the Late Bronze Egyptian Garrison at Beth Shan", in McGovern, P.E. (ed,), Cross-Craft and Cultural Interactions in Ceramics, [Ceramics and Civilisation 4, ed. Kingery, W.D.], Westerville: American Ceramic Society, 1989, pp. 147–194.

- McGovern, Patrick E. [1990], "The Ultimate Attire: Jewelry from a Canaanite Temple at Beth Shan", Expedition 32 (1990), pp. 16–23.

- McGovern, Patrick E. [1994], "Were the Sea Peoples at Beth Shan?", in Lemche, N.P. & Müller, M. (eds), Fra dybet: Festskrift til John Strange, [Forum for Bibelsk Eksegese 5], Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanus and University of Copenhagen, 1994, pp. 144–156.

- Khamis, E., "Two wall mosaic inscriptions from the Umayyad market place in Bet Shean/Baysan", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 64 (2001), pp. 159–76.

- McGovern, P.E., Fleming, S.J. & Swann, C.P. [1993], "The Late Bronze Egyptian Garrison at Beth Shan: Glass and Faience Production and Importation in the Late New Kingdom", BASOR 290-91 (1993), pp. 1–27.

- Mazar, A., Ziv-Esudri, Adi and Cohen-Weinberger, Anet [2000], "The Early Bronze Age II–III at Tel Beth Shean: Preliminary Observations", in Philip, G. and Baird, D. (eds), Ceramics and Change in the Early Bronze Age of the Southern Levant, [Levantine Archaeology 2], Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2000, pp. 255–278.

- Mazar, Amihai [1990], "The Excavations at Tel Beth-Shean", Eretz-Israel 21 (1990), pp. 197–211 (יברית).

- Mazar, Amihai [1992], "Temples of the Middle and Late Bronze Ages and the Iron Age", in Kempinski, A. and Reich, R. (eds), The Architecture of Ancient Israel from the Prehistoric to the Persian Periods — in Memory of Immanual (Munya) Dunayevsky, Jerusalem: IES, 1992, pp. 161–187.

- Mazar, Amihai [1993a], "The Excavations at Tel Beth-Shean in 1989–1990", in Biran, A. and Aviram, J. (eds), Biblical Archaeology Today, 1990 – Proceedings of the Second International Congress on Biblical Archaeology, Jerusalem, 1990, Jerusalem: IES, 1993, pp. 606–619.

- Mazar, Amihai 1993b, "Beth Shean in the Iron Age: Preliminary Report and Conclusions of the 1990–1991 Excavations", IEJ 43.4 (1993), pp. 201–229.

- Mazar, Amihai [1994], "Four Thousand Years of History at Tel Beth-Shean", Qadmoniot 27.3–4 (1994), pp. 66–83 (יברית).

- [1997a], "Four Thousand Years of History at Tel Beth-Shean—An Account of the Renewed Excavations", BA 60.2 (1997), pp. 62–76.

- Mazar, Amihai [1997b], "The Excavations at Tel Beth Shean during the Years 1989–94", in Silberman, N.A. and Small, D. (eds), The Archaeology of Israel – Constructing the Past, Interpreting the Present, [JSOT Supplement Series 237], Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1997, pp. 144–164.

- Mazar, Amihai [2003], "Beth Shean in the Second Millennium BCE: From Canaanite Town to Egyptian Stronghold", in Bietak, M. (ed.), The Synchronisation of Civilisations in the Eastern Mediterranean in the SEcond Millennium BC, II. Proceedings of the SCIEM 2000-EuroConference Haindorf, 2–7 May 2001, Vienna, 2003, pp. 323–339.

- Mazar, Amihai [2006], "Tel Beth-Shean and the Fate of Mounds in the Intermediate Bronze Age", in Gitin, S., Wright, J.E. and Dessel, J.P. (eds), Confronting the Past—Archaeological and Historical Essays on Ancient Israel in Honor of William G. Dever, Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2006, pp. 105–118. ISBN 1-57506-117-1

- Mullins, Robert A. [2006], "A Corpus of Eighteenth Dynasty Egyptian-Style Pottery from Tel Beth-Shean", in Maeir, A.M. and Miroschedji, P. de (eds), "I Will Speak the Riddle of Ancient Times"—Archaeological and Historical Studies in Honor of Amihai Mazar on the Occasion of His Sixtieth Birthday, Volume 1, Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2006, pp. 247–262. ISBN 1-57506-103-1

- Oren, Eliezer D. [1973], The Northern Cemetery of Beth-Shean, [Museum Monograph of the University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania], E.J. Brill: Leiden, 1973.

- Porter, R.M. [1994–1995], "Dating the Beth Shean Temple Sequence", Journal of the Ancient Chronology Forum 7 (1994–95), pp. 52–69.

- Porter, R.M. [1998], "An Egyptian Temple at Tel Beth Shean and Ramesses IV", in Eyre, C. (ed.), Seventh International Congress of Egyptologists, Cambridge, 3–9 September 1995, [Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 82], Uitgeverij Peeters: Leuven, 1998, pp. 903–910.

- Sweeney, Deborah [1998], "The Man on the Folding Chair: An Egyptian Relief from Beth Shean", IEJ 48 (1998), pp. 38–53.

- Thompson, T.O. (1970). Mekal, the God of Beth Shean. Leiden: E.J. Brill. ISBN 9789004022683.

- Walmsley, A., 'Economic Developments and the Nature of Settlement in the Towns and Countryside of Syria-Palestine, ca. 565–800', Dumbarton Oaks Papers 61 (2007), pp. 319–52.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bet She'an. |

- Beit She'an National Park – official site

- BET(H)-SHEAN Jewish Virtual Library

- Ilan Phahima and Yoram Saad, Scythopolis: Conservation of the Roman Bridge, Israel Antiquities Authority Site – Conservation Department

- Survey of Western Palestine, 1880 Map of Beit Shean (Beisân), Map 9: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Air photo map of Beisan, 1945. Eran Laor Cartographic Collection, The National Library of Israel.

- Map of Beisan, 1929. Survey of Palestine. Eran Laor Cartographic Collection, The National Library of Israel.