Chorazin

Chorazin (/koʊˈreɪzɪn/; Hebrew: כורזים, Korazim; also Karraza, Kh. Karazeh, Chorizim, Kerazeh, Korazin), is the biblical site identified as the modern-day village of Karraza. It was an ancient village in the Korazim Plateau in the Galilee, two and a half miles from Capernaum on a hill above the northern shore of the Sea of Galilee.

כורזים | |

Ancient synagogue at Chorazim | |

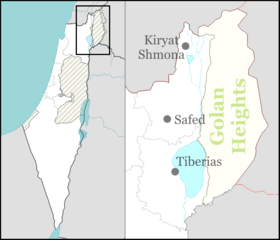

Shown within northeastern Israel | |

| Location | Northern District, Israel |

|---|---|

| Region | Korazim Plateau, Galilee |

| Coordinates | 32°54′41″N 35°33′50″E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | Ruined |

History

Chorazin, along with Bethsaida and Capernaum, was named in the gospels of Matthew and Luke as "cities" (more likely just villages) in which Jesus performed mighty works. However, because these towns rejected his work ("they had not changed their ways"), they were subsequently cursed (Matthew 11:20-24; Luke 10:13-15). The gospels make no other mention of Chorazin or what works had occurred there. Due to the condemnation of Jesus, the influential Apocalypse of Pseudo-Methodius predicted that the Antichrist would be conceived in Chorazin.[1]

The Babylonian Talmud (Menahot, 85a) mentions that Chorazin was a town known for its grain.[2]

Two settlement phases have been proposed based on coin and pottery findings.[3]

Theologian John Lightfoot suggested that Chorazin might have been an area around Cana in Galilee, rather than a single city/village:

- What if, under this name, Cana be concluded, and some small country adjacent, which, from its situation in a wood, might be named "Chorazin", that is, 'the woody country'? Cana is famous for the frequent presence and miracles of Christ. But away with conjecture, when it grows too bold.[4]

Archaeology

In his expeditions to the Holy Land in the nineteenth century, Edward Robinson questioned local residents about the whereabouts of a site matching the description of Chorazin, but no one recognized the name or could provide any information.[5]

Chorazin is now the site of a National Archaeological Park. Extensive excavations and a survey were carried out in 1962-1964. Excavations at the site were resumed in 1980-1987.

The majority of the structures are made from black basalt, a volcanic rock found locally.[6] The main settlement dates to the 3rd and 4th centuries. A mikvah, or ritual bath, was also found at the site. The handful of olive millstones used in olive oil extraction found suggest a reliance on the olive for economic purposes, like a number of other villages in ancient Galilee.

The town's ruins are spread over an area of 25 acres (100,000 m2), subdivided into five separate quarters, with a synagogue in the centre. The large, impressive Synagogue which was built with black basalt stones and decorated with Jewish motifs is the most striking survival. Close by is a ritual bath, surrounded by public and residential buildings.

In 1926, archaeologists discovered the "Seat of Moses," carved from a basalt block. According to the New Testament, this is where the reader of the Torah sat (Matthew 23:1-3).[7]

In May–June 2004, a small-scale salvage excavation was conducted by the Israel Antiquities Authority along the route of an ancient road north of Moshav Amnun. In the literature, the road is referred to as “The Way through Korazim.” It crossed the Chorazin plateau from west to east, branching off from the main Cairo–Damascus road that ran northeast toward Daughters of Jacob Bridge.[8]

Synagogues

The only synagogue visible today was built in the late 3rd century, destroyed in the 4th century, and rebuilt in the 6th century.[9]

An unusual feature in an ancient synagogue is the presence of three-dimensional sculpture, a pair of stone lions. A similar pair of three-dimensional lions was found in the synagogue at Kfar Bar'am.[10] Other carvings, which are thought to have originally been brightly painted, feature images of wine-making, animals, a Medusa, an armed soldier, and an eagle.[11]

Jacob Ory, who excavated the site in 1926 on behalf of the British Mandate Department of Antiquities, wrote about a second synagogue ca. 200 m west of the first one, and he described it in detail. Later excavations, however, have not been able to find the remains noted by him.[12]

Geomorphology

The term Korazim Plateau is used to define a geomorphological feature set between the Hula Basin and the Sea of Galilee. It is an elevated pressure-ridge within the Dead Sea Transform (DST) which acted as a barrier towards the waters of the Mediterranean when these flooded the lower-laying part of the DST, between what are now the Sea of Galilee and the Dead Sea basins, during the Pliocene transgression. The Korazim block as well as the higher elevation of the Hula Basin meant that the latter did not receive any marine water during that process.[13]

See also

- Ancient synagogues in the Palestine region

- Archaeology of Israel

- Jesus trail

- National parks of Israel

- Oldest synagogues in the world

- Woes to the unrepentant cities, pronounced by Jesus and which included Chorazin

References

- Alexander, Paul Julius (1985). The Byzantine Apocalyptic Tradition. pp. 195–196. ISBN 0520049985.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Three Woes". Archived from the original on 2016-03-10. Retrieved 2016-03-10.

- Jews and Christians in the Holy Land: Palestine in the Fourth Century

- Lightfoot, J., A Commentary on the New Testament From the Talmud and Hebraica: Matthew, accessed 6 January 2017

- The Christian remembrancer

- Ancient Jewish Art and Archaeology in the Land of Israel, Rāḥēl Ḥak̲lîlî

- "Three Woes". Archived from the original on 2016-03-10. Retrieved 2016-03-10.

- Kh. Umm el-Kalkha

- Avraham Negev; Shimon Gibson (July 2005). Archaeological encyclopedia of the Holy Land. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-8264-8571-7. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- Steven Fine (2005). Art and Judaism in the Greco-Roman world: toward a new Jewish archaeology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-84491-8. Retrieved 15 May 2011. p.190

- Steven Fine (2005). Art and Judaism in the Greco-Roman world: toward a new Jewish archaeology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-84491-8. Retrieved 15 May 2011. p.92

- Anders Runesson; Donald D. Binder; Birger Olsson (2008). The Ancient Synagogue from its Origins to 200 C.E.. Brill. p. 32. ISBN 978-90-04-16116-0.

- Uri Kafri; Yoseph Yechieli (2010). Groundwater Base Level Changes and Adjoining Hydrological Systems. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 123. ISBN 978-3642139444.

Further reading

- Z. Yeivin, The Synagogue at Korazim; The 1962 - 1964, 1980 - 1987 Excavations, Israel Antiquities Authority Reports, Israel Antiquities Authority, 2000.

- New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land vols. 1-5. Ed. E. Stern; Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society and Carta (1993-2008).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chorazin. |

- Chorazin—Sitting in the Seat but Missing the Message from waynestiles.com

- Strong's G5523

- Pictures of Chorazin

- The Ancient Synagogue of Chorazin from a Jewish tourism site

- Chorazin University of Notre Dame, New Testament Professor David E. Aune

- Ancient Chorazin Comes Back to Life by Ze’ev Yeivin of the Biblical Archaeology Society.