Beshalach

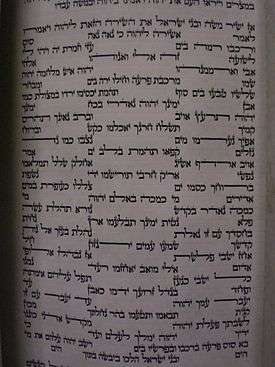

Beshalach, Beshallach, or Beshalah (בְּשַׁלַּח — Hebrew for "when [he] let go," the second word and first distinctive word in the parashah) is the sixteenth weekly Torah portion (פָּרָשָׁה, parashah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the fourth in the Book of Exodus. It constitutes Exodus 13:17–17:16. In this parashah, Pharaoh changes his mind and chases after the Israelite people with his army, trapping them at the Sea of Reeds. God commands Moses to split the sea, allowing them to pass, then closes the sea back upon the Egyptian army. There are the miracles of manna and clean water. The nation of Amalek attacks and the Israelite people are victorious.

The parashah is made up of 6,423 Hebrew letters, 1,681 Hebrew words, 116 verses, and 216 lines in a Torah Scroll (סֵפֶר תּוֹרָה, Sefer Torah).[1]

Jews read it the sixteenth Sabbath after Simchat Torah, in January or February.[2] As the parashah describes God's deliverance of the Israelites from Egypt, Jews also read part of the parashah, Exodus 13:17–15:26, as the initial Torah reading for the seventh day of Passover. And Jews also read the part of the parashah about Amalek, Exodus 17:8–16, on Purim, which commemorates the story of Esther and the Jewish people's victory over Haman's plan to kill the Jews, told in the book of Esther.[3] Esther 3:1 identifies Haman as an Agagite, and thus a descendant of Amalek. Numbers 24:7 identifies the Agagites with the Amalekites. A Midrash tells that between King Agag's capture by Saul and his killing by Samuel, Agag fathered a child, from whom Haman in turn descended.[4]

The parashah is notable for the "Song of the Sea," which is traditionally chanted using a different melody and is written by the scribe using a distinctive brick-like pattern in the Torah scroll. The Sabbath when it is read is known as Shabbat Shirah. Some communities customs for this day, include feeding birds and reciting the "Song of the Sea" out loud in the regular prayer service. The song of the sea is sometimes known as the Shirah (song) in some western Jewish synagogues.

The haftarah for Beshalach tells the story of Deborah. At 52 verses, it is the longest haftarah.

Readings

In traditional Sabbath Torah reading, the parashah is divided into seven readings, or עליות, aliyot. In the Masoretic Text of the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible), Parashat Beshalach has eight "open portion" (פתוחה, petuchah) divisions (roughly equivalent to paragraphs, often abbreviated with the Hebrew letter פ (peh)). Parashat Beshalach has four further subdivisions, called "closed portion" (סתומה, setumah) divisions (abbreviated with the Hebrew letter ס (samekh)) within the open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) divisions. The first open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) divides the first reading (עליה, aliyah). The second open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) covers the balance of the first and all of the second readings (עליות, aliyot). The third open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) is coincident with the third reading (עליה, aliyah). The fourth open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) covers the fourth and fifth readings (עליות, aliyot). The fifth open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) is coincident with the sixth reading (עליה, aliyah). The sixth and seventh open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) divisions divide the seventh reading (עליה, aliyah). And the eighth open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) is coincident with the maftir (מפטיר) reading that concludes the parashah. Closed portion (סתומה, setumah) divisions separate the fourth and fifth readings (עליות, aliyot), and divide the fifth and sixth readings (עליות, aliyot).[5]

.jpg)

First reading — Exodus 13:17–14:8

In the first reading (עליה, aliyah), when Pharaoh let the Israelites go, God led the people roundabout by way of the Sea of Reeds.[6] Moses took the bones of Joseph with them.[7] God went before them in a pillar of cloud by day and in a pillar of fire by night.[8] The first open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) ends here with the end of chapter 13.[9]

In the continuation of the reading (עליה, aliyah) in chapter 14, God told Moses to tell the Israelites to turn back and encamp by the sea, so that Pharaoh might think that the Israelites were trapped and follow after them.[10] When Pharaoh learned that the people had fled, he had a change of heart, and he chased the Israelites with chariots.[11] The first reading (עליה, aliyah) ends here.[12]

Second reading — Exodus 14:9–14

In the short second reading (עליה, aliyah), Pharaoh overtook the Israelites by the sea.[13] Greatly frightened, the Israelites cried out to God and complained to Moses.[14] Moses told the people not to fear, for God would fight for them.[15] The second reading (עליה, aliyah) and second open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) end here.[16]

Third reading — Exodus 14:15–25

In the third reading (עליה, aliyah), God told Moses to lift up his rod, hold out his arm, and split the sea.[17] Moses did so, and God drove back the sea with a strong east wind, and the Israelites marched through on dry ground, the waters forming walls on their right and left.[18] The Egyptians pursued, but God slowed them by locking their chariot wheels.[19] The third reading (עליה, aliyah) and the third open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) end here.[20]

Fourth reading — Exodus 14:26–15:26

In the long fourth reading (עליה, aliyah), on God's instruction, Moses held out his arm, and the waters covered the chariots, the horsemen, and all the Egyptians.[21] Moses and the Israelites — and then Miriam — sang a song to God, celebrating how God hurled horse and driver into the sea.[22] The fourth reading (עליה, aliyah) and a closed portion (סתומה, setumah) end here.[23]

.jpg)

Fifth reading — Exodus 15:27–16:10

In the short fifth reading (עליה, aliyah), the Israelites went three days into the wilderness and found no water.[24] When they came to Marah, they could not drink the bitter water, so they grumbled against Moses.[25] God showed Moses a piece of wood to throw into the water, and the water became sweet.[26] God told Moses that if he would diligently hearken to God and obey God's commandments, then God would give the Israelites none of the diseases that God had given the Egyptians.[27] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[28]

.jpg)

In the continuation of the reading (עליה, aliyah), the Israelites traveled to the springs and palms of Elim, and then came to the wilderness of Sin and grumbled in hunger against Moses and Aaron.[29] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[30]

In the continuation of the reading (עליה, aliyah), God told Moses that God would rain bread from heaven, and twice as much on the sixth day.[31] Moses and Aaron told the Israelites that they would see God's glory, for God had heard their murmurings against God, and the Israelites saw God's glory appear in a cloud.[32] The fifth reading (עליה, aliyah) and the fourth open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) end here.[33]

Sixth reading — Exodus 16:11–36

In the sixth reading (עליה, aliyah), God heard their grumbling, and in the evening quail covered the camp, and in the morning fine flaky manna covered the ground like frost.[34] The Israelites gathered as much of it as they required; those who gathered much had no excess, and those who gathered little had no deficiency.[35] Moses instructed none to leave any of it over until morning, but some did, and it became infested with maggots and stank.[36] On the sixth day they gathered double the food, Moses instructed them to put aside the excess until morning, and it did not turn foul the next day, the Sabbath.[37] Moses told them that on the Sabbath, they would not find any manna on the plain, yet some went out to gather and found nothing.[38] A closed portion (סתומה, setumah) ends here.[39]

In the continuation of the reading (עליה, aliyah), Moses ordered that a jar of the manna be kept throughout the ages.[40] The Israelites ate manna 40 years.[41] The sixth reading (עליה, aliyah) and the fifth open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) end here with the end of chapter Exodus 16.[42]

Seventh reading — Exodus 17:1–16

In the seventh reading (עליה, aliyah), in chapter 17, when the Israelites encamped at Rephidim, there was no water and the people quarreled with Moses, asking why Moses brought them there just to die of thirst.[43] God told Moses to strike the rock at Horeb to produce water, and they called the place Massah (trial) and Meribah (quarrel).[44] The sixth open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) ends here.[45]

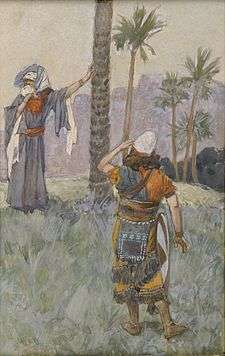

In the continuation of the reading (עליה, aliyah), Amalek attacked Israel at Rephidim.[46] Moses stationed himself on the top of the hill, with the rod of God in his hand, and whenever Moses held up his hand, Israel prevailed; but whenever he let down his hand, Amalek prevailed.[47] When Moses grew weary, he sat on a stone, while Aaron and Hur supported his hands, and Joshua overwhelmed Amalek in battle.[48] The seventh open portion (פתוחה, petuchah) ends here.[49]

In the maftir (מפטיר) reading that concludes the parashah,[49] God instructed Moses to inscribe a document as a reminder that God would utterly blot out the memory of Amalek.[50] The seventh reading (עליה, aliyah), the eighth open portion (פתוחה, petuchah), and the parashah end here.[49]

Readings according to the triennial cycle

Jews who read the Torah according to the triennial cycle of Torah reading read the parashah according to the following schedule:[51]

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016–2017, 2019–2020 . . . | 2017–2018, 2020–2021 . . . | 2018–2019, 2021–2022 . . . | |

| Reading | 13:17–15:26 | 14:15–16:10 | 14:26–17:16 |

| 1 | 13:17–22 | 14:15–20 | 14:26–15:21 |

| 2 | 14:1–4 | 14:21–25 | 15:22–26 |

| 3 | 14:5–8 | 14:26–15:21 | 15:27–16:10 |

| 4 | 14:9–14 | 15:22–26 | 16:11–27 |

| 5 | 14:15–20 | 15:27–16:3 | 16:28–36 |

| 6 | 14:21–25 | 16:4–7 | 17:1–7 |

| 7 | 14:26–15:26 | 16:8–10 | 17:8–16 |

| Maftir | 15:22–26 | 16:8–10 | 17:14–16 |

In inner-biblical interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these Biblical sources:[52]

Exodus 16:22–30 refers to the Sabbath. Commentators note that the Hebrew Bible repeats the commandment to observe the Sabbath 12 times.[53]

Genesis 2:1–3 reports that on the seventh day of Creation, God finished God's work, rested, and blessed and hallowed the seventh day.

The Sabbath is one of the Ten Commandments. Exodus 20:7–10[54] commands that one remember the Sabbath day, keep it holy, and not do any manner of work or cause anyone under one's control to work, for in six days God made heaven and earth and rested on the seventh day, blessed the Sabbath, and hallowed it. Deuteronomy 5:11–14[55] commands that one observe the Sabbath day, keep it holy, and not do any manner of work or cause anyone under one's control to work — so that one's subordinates might also rest — and remember that the Israelites were servants in the land of Egypt, and God brought them out with a mighty hand and by an outstretched arm.

In the incident of the manna (מָן, man) in Exodus 16:22–30, Moses told the Israelites that the Sabbath is a solemn rest day; prior to the Sabbath one should cook what one would cook, and lay up food for the Sabbath. And God told Moses to let no one go out of one's place on the seventh day.

In Exodus 31:12–17, just before giving Moses the second Tablets of Stone, God commanded that the Israelites keep and observe the Sabbath throughout their generations, as a sign between God and the children of Israel forever, for in six days God made heaven and earth, and on the seventh day God rested.

In Exodus 35:1–3, just before issuing the instructions for the Tabernacle, Moses again told the Israelites that no one should work on the Sabbath, specifying that one must not kindle fire on the Sabbath.

In Leviticus 23:1–3, God told Moses to repeat the Sabbath commandment to the people, calling the Sabbath a holy convocation.

The prophet Isaiah taught in Isaiah 1:12–13 that iniquity is inconsistent with the Sabbath. In Isaiah 58:13–14, the prophet taught that if people turn away from pursuing or speaking of business on the Sabbath and call the Sabbath a delight, then God will make them ride upon the high places of the earth and will feed them with the heritage of Jacob. And in Isaiah 66:23, the prophet taught that in times to come, from one Sabbath to another, all people will come to worship God.

The prophet Jeremiah taught in Jeremiah 17:19–27 that the fate of Jerusalem depended on whether the people obstained from work on the Sabbath, refraining from carrying burdens outside their houses and through the city gates.

The prophet Ezekiel told in Ezekiel 20:10–22 how God gave the Israelites God's Sabbaths, to be a sign between God and them, but the Israelites rebelled against God by profaning the Sabbaths, provoking God to pour out God's fury upon them, but God stayed God's hand.

In Nehemiah 13:15–22, Nehemiah told how he saw some treading wine presses on the Sabbath, and others bringing all manner of burdens into Jerusalem on the Sabbath day, so when it began to be dark before the Sabbath, he commanded that the city gates be shut and not opened till after the Sabbath and directed the Levites to keep the gates to sanctify the Sabbath.

In early nonrabbinic interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these early nonrabbinic sources:[56]

1 Maccabees 2:27–38 told how in the 2nd century BCE, many followers of the pious Jewish priest Mattathias rebelled against the Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes. Antiochus's soldiers attacked a group of them on the Sabbath, and when the Pietists failed to defend themselves so as to honor the Sabbath (commanded in, among other places, Exodus 16:22–30), a thousand died. 1 Maccabees 2:39–41 reported that when Mattathias and his friends heard, they reasoned that if they did not fight on the Sabbath, they would soon be destroyed. So they decided that they would fight against anyone who attacked them on the Sabbath.[57]

In classical rabbinic interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these rabbinic sources from the era of the Mishnah and the Talmud:[58]

Exodus chapter 13

The Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael interpreted the words "God led them not by the way of the land of the Philistines, although that was near" in Exodus 13:17 to indicate that God recognized that the way would have been nearer for the Israelites to return to Egypt.[59]

A Midrash compared the words of Exodus 13:17, "God led the people about," to a merchant who bought a cow for use in his home and not for slaughter. As the merchant's house was near the slaughterhouse, he thought to himself that he had better lead the new cow home by another route, for if he led the cow past the slaughterhouse and it saw the blood there, it might turn tail and flee. Similarly, as the inhabitants of Gaza, Ashkelon, and the land of the Philistines were ready to rise against the Israelites on their departure from Egypt, God thought that the Israelites must not see the battle, lest they return to Egypt, as God says in Exodus 13:17, "Lest peradventure the people repent when they see war, and they return to Egypt." So God led them by another route.[60]

Rabbi Jose ben Hanina taught that God did not lead the Israelites by the way of the land of the Philistines (as reported in Exodus 13:17) because Abimelech's grandson was still alive, and God did not want the Israelites to violate Abraham's oath of Genesis 21:23–24 not to deal falsely with Abimelech, his son, or his grandson.[61]

The Rabbis taught in a Baraita that on the days of the 8-day Passover holiday, Jews read the various passages in the Torah relating to Passover. Thus, on the seventh day of Passover, Jews read Exodus 13:17–15:26 and as haftarah 2 Samuel 22:1–51.[62]

A Midrash employed a fanciful translation of Exodus 13:18 to imagine God's response to the Israelites' complaints in the wilderness. The Midrash taught that God asked the Israelites whether when a mortal king went into the wilderness, the king found there the same ease, the same food, or the same drink that he enjoyed in his own palace. The Midrash taught that the Israelites, however, were slaves in Egypt, and God brought them out of there and caused them to recline on lordly couches. In support of this, the Midrash reread Exodus 13:18, "But God led the people about, (וַיַּסֵּב, vayaseiv) by the way of the wilderness," reading וַיַּסֵּב, vayaseiv, to mean God caused them "to recline" (using the same root סבב, svv) in the manner of kings reclining upon their couches.[63]

The Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael interpreted the word translated as "armed" (חֲמֻשִׁים, chamushim) in Exodus 13:18 to mean that only one out of five (חֲמִשָּׁה, chamishah) of the Israelites in Egypt left Egypt; and some say that only one out of 50 did; and others say that only one out of 500 did.[64]

.jpg)

The Mishnah cited Exodus 13:19 for the proposition that Providence treats a person measure for measure as that person treats others. And so because, as Genesis 50:7–9 relates, Joseph had the merit to bury his father Jacob and none of his brothers were greater than he was, so Joseph merited the greatest of Jews, Moses, to attend to his bones, as reported in Exodus 13:19. And Moses, in turn, was so great that none but God attended him, as Deuteronomy 34:6 reports that God buried Moses.[65] Similarly, the Tosefta cited Exodus 13:19 for the proposition that as Joseph had the merit of burying Jacob, so it was that only Moses took the trouble to care for Joseph's bones. The Tosefta deduced from this that the rest of the Israelites were occupied with plunder, but Moses occupied himself with performing a commandment. When the Israelites saw Moses caring for Joseph's bones, they concluded that they should let Moses do so, so that Joseph's honor would be greater when his rites were taken care of by great people instead of unimportant people.[66]

Citing Exodus 13:19, the Tosefta taught that just as "Moses took the bones of Joseph with him" into the Levites' camp, so one who was impure by reason of corpse contamination — and even a corpse — could enter the Temple Mount.[67]

A Midrash illustrated a precept to finish what one starts by citing how Moses began performing a commandment by taking the bones of Joseph with him, as Exodus 13:19 reports, but failed to complete the task. Reading Deuteronomy 30:11–14, "For this commandment that I command you this day . . . is very near to you, in your mouth, and in your heart," a Midrash interpreted "heart" and "mouth" to symbolize the beginning and end of fulfilling a precept and thus read Deuteronomy 30:11–14 as an exhortation to complete a good deed once started. Thus Rabbi Hiyya bar Abba taught that if one begins a precept and does not complete it, the result will be that he will bury his wife and children. The Midrash cited as support for this proposition the experience of Judah, who began a precept and did not complete it. When Joseph came to his brothers and they sought to kill him, as Joseph's brothers said in Genesis 37:20, "Come now therefore, and let us slay him," Judah did not let them, saying in Genesis 37:26, "What profit is it if we slay our brother?" and they listened to him, for he was their leader. And had Judah called for Joseph's brothers to restore Joseph to their father, they would have listened to him then, as well. Thus because Judah began a precept (the good deed toward Joseph) and did not complete it, he buried his wife and two sons, as Genesis 38:12 reports, "Shua's daughter, the wife of Judah, died," and Genesis 46:12 further reports, "Er and Onan died in the land of Canaan." In another Midrash reading "heart" and "mouth" in Deuteronomy 30:11–14 to symbolize the beginning and the end of fulfilling a precept, Rabbi Levi said in the name of Hama bar Hanina that if one begins a precept and does not complete it, and another comes and completes it, it is attributed to the one who has completed it. The Midrash illustrated this by citing how Moses began a precept by taking the bones of Joseph with him, as Exodus 13:19 reports, "And Moses took the bones of Joseph with him." But because Moses never brought Joseph's bones into the Land of Israel, the precept is attributed to the Israelites, who buried them, as Joshua 24:32 reports, "And the bones of Joseph, which the children of Israel brought up out of Egypt, they buried in Shechem." Joshua 24:32 does not say, "Which Moses brought up out of Egypt," but "Which the children of Israel brought up out of Egypt." And the Midrash explained that the reason that they buried Joseph's bones in Shechem could be compared to a case in which some thieves stole a cask of wine, and when the owner discovered them, the owner told them that after they had consumed the wine, they needed to return the cask to its proper place. So when the brothers sold Joseph, it was from Shechem that they sold him, as Genesis 37:13 reports, "And Israel said to Joseph: 'Do not your brothers feed the flock in Shechem?'" God told the brothers that since they had sold Joseph from Shechem, they needed to return Joseph's bones to Shechem. And as the Israelites completed the precept, it is called by their name, demonstrating the force of Deuteronomy 30:11–14, "For this commandment that I command you this day . . . is very near to you, in your mouth, and in your heart."[68]

Rabbi Jose the Galilean taught that the "certain men who were unclean by the dead body of a man, so that they could not keep the Passover on that day" in Numbers 9:6 were those who bore Joseph's coffin, as implied in Genesis 50:25 and Exodus 13:19. The Gemara cited their doing so to support the law that one who is engaged on one religious duty is free from any other.[69]

The Gemara told that Rav Joseph's wife used to kindle the Sabbath lights late (just before nightfall). Rav Joseph told her that it was taught in a Baraita that the words of Exodus 13:22, "the pillar of cloud by day, and the pillar of fire by night, departed not," teach that the pillar of cloud overlapped the pillar of fire, and the pillar of fire overlapped the pillar of cloud. So she thought of lighting the Sabbath lights very early. But an elder told her that one may kindle when one chooses, provided that one does not light too early (as it would not evidently honor the Sabbath) or too late (later than just before nightfall).[70]

Exodus chapter 14

Reading Isaiah 43:12, "I have declared, and I have saved, and I have announced," a Midrash taught that God "declared" to Egypt that the Israelites had fled, so that they would hear, pursue after them, and be drowned in the sea, as Exodus 14:5 reports, "And it was told the king of Egypt that the people had fled." God "saved," as Exodus 14:30 reports, "Thus the Lord saved Israel that day." And God "announced" to the rest of the world, as Exodus 15:14 says, "The peoples have heard, they tremble."[71]

A Midrash taught that a slave's master wept when slaves escaped, while the slaves sang when they had thrown off bondage. So the Egyptians wept when the Israelites escaped (as Exodus 14:5 reports). The Israelites, however, chanted a song when they were released from bondage.[72]

Reading Exodus 14:6, "And he made ready his chariot," to indicate that Pharaoh prepared his chariot personally, a Midrash remarked that surely he had plenty of slaves who could have done so for him. The Midrash concluded that the intensity of Pharaoh's hate thus upset the natural order.[73]

Rabban Gamaliel said that the Egyptians pursued after the Israelites as far as the Reed Sea, and encamped behind them. The enemy was behind them and the sea was in front of them. The Israelites saw the Egyptians, and became greatly afraid. The Israelites cast away all their Egyptian abominations, repented sincerely, and called upon God, as Exodus 14:10 reports, "And when Pharaoh drew near, the children of Israel lifted up their eyes." Moses saw the Israelites' anguish, and prayed on their behalf. God replied to Moses in Exodus 14:15, "Speak to the children of Israel, that they go forward."[74]

Rabbi Meir taught that when the Israelites stood by the sea, the tribes competed with each other over who would go into the sea first. The tribe of Benjamin went first, as Psalm 68:28 says: "There is Benjamin, the youngest, ruling them (rodem)," and Rabbi Meir read rodem, "ruling them," as rad yam, "descended into the sea." Then the princes of Judah threw stones at them, as Psalm 68:28 says: "the princes of Judah their council (rigmatam)," and Rabbi Meir read rigmatam as "stoned them." For that reason, Benjamin merited hosting the site of God's Temple, as Deuteronomy 33:12 says: "He dwells between his shoulders." Rabbi Judah answered Rabbi Meir that in reality, no tribe was willing to be the first to go into the sea. Then Nahshon ben Aminadab stepped forward and went into the sea first, praying in the words of Psalm 69:2–16, "Save me O God, for the waters come into my soul. I sink in deep mire, where there is no standing . . . . Let not the water overwhelm me, neither let the deep swallow me up." Moses was then praying, so God prompted Moses, in words parallel those of Exodus 14:15, "My beloved ones are drowning in the sea, and you prolong prayer before Me!" Moses asked God, "Lord of the Universe, what is there in my power to do?" God replied in the words of Exodus 14:15–16, "Speak to the children of Israel, that they go forward. And lift up your rod, and stretch out your hand over the sea, and divide it; and the children of Israel shall go into the midst of the sea on dry ground." Because of Nahshon's actions, Judah merited becoming the ruling power in Israel, as Psalm 114:2 says, "Judah became His sanctuary, Israel His dominion," and that happened because, as Psalm 114:3 says, "The sea saw [him], and fled."[75]

Similarly, Rabbi Akiva said that the Israelites advanced to enter the Reed Sea, but they turned backwards, fearing that the waters would come over them. The tribe of Judah sanctified God's Name and entered the sea first, as Psalm 114:2 says, "Judah became his sanctuary (in order to sanctify God), Israel his dominion." The Egyptians wanted to follow the Israelites, but they turned back, fearing that the waters would return over them. God appeared before them like a man riding on the back of a mare, as it is said in Song of Songs 1:9, "To a steed in Pharaoh's chariots." Pharaoh's horse saw the mare of God, and it neighed and ran into the sea after it.[76]

Reading Exodus 14:15, "And the Lord said to Moses: 'Why do you cry to Me? Speak to the children of Israel, that they go forward," Rabbi Eliezer taught that God was telling Moses that there is a time to pray briefly and a time to pray at length. God was telling Moses that God's children were in trouble, the sea cut them off, the enemy pursued, and yet Moses stood and said a long prayer! God told Moses that it was time to cut short his prayer and act.[77]

Rabbi (Judah the Prince) taught that in Exodus 14:15, God was saying that the Israelites' faith in God was sufficient cause for God to divide the sea for them. For notwithstanding their fear, the Israelites had believed in God and followed Moses that far. Rabbi Akiva taught that for Jacob's sake God divided the sea for Jacob's descendants, for in Genesis 28:14, God told Jacob, "You shall spread abroad to the west, and to the east."[78]

Rabbi Eliezer said that on the third day of Creation, when God said in Genesis 1:9, "Let the waters be gathered together," the waters of the Reed Sea congealed and were made into twelve valleys (or paths), corresponding to the twelve tribes of Israel. And they were made into walls of water between each path, and between each path were windows. The Israelites could see one another, and they saw God walking before them, but they did not see the heels of God's feet, as Psalm 77:19 says, "Your way was in the sea, and your paths in the great waters, and your footsteps were not known."[79]

Rabbi Johanan taught that God does not rejoice in the downfall of the wicked. Rabbi Johanan interpreted the words zeh el zeh in the phrase "And one did not come near the other all the night" in Exodus 14:20 to teach that when the Egyptians were drowning in the sea, the ministering angels wanted to sing a song of rejoicing, as Isaiah 6:3 associates the words zeh el zeh with angelic singing. But God rebuked them: "The work of my hands is being drowned in the sea, and you want to sing songs?" Rabbi Eleazar replied that a close reading of Deuteronomy 28:63 shows that God does not rejoice personally, but does make others rejoice.[80]

.jpg)

The Midrash taught that the six days of darkness occurred in Egypt, while the seventh day of darkness was a day of darkness of the sea, as Exodus 14:20 says: "And there was the cloud and the darkness here, yet it gave light by night there." So God sent clouds and darkness and covered the Egyptians with darkness, but gave light to the Israelites, as God had done for them in Egypt. Hence Psalm 27:1 says: "The Lord is my light and my salvation." And the Midrash taught that in the Messianic Age, as well, God will bring darkness to sinners, but light to Israel, as Isaiah 60:2 says: "For, behold, darkness shall cover the earth, and gross darkness the peoples; but upon you the Lord will shine."[81]

.jpg)

The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer recounted that Moses cried out to God that the enemy was behind them and the sea in front of them, and asked which way they should go. So God sent the angel Michael, who became a wall of fire between the Israelites and the Egyptians. The Egyptians wanted to follow after the Israelites, but they are unable to come near because of the fire. The angels saw the Israelites' misfortune all the night, but they uttered neither praise nor sanctification, as Exodus 14:20 says, "And the one came not near the other all the night." God told Moses (as Exodus 14:16 reports) to "Stretch out your hand over the sea, and divide it." So (as Exodus 14:21 reports) "Moses stretched out his hand over the sea," but the sea refused to be divided. So God looked at the sea, and the waters saw God's Face, and they trembled and quaked, and descended into the depths, as Psalm 77:16 says, "The waters saw You, O God; the waters saw You, they were afraid: the depths also trembled." Rabbi Eliezer taught that on the day that God said Genesis 1:9, "Let the waters be gathered together," the waters congealed, and God made them into twelve valleys, corresponding to the twelve tribes, and they were made into walls of water between each path, and the Israelites could see each other, and they saw God, walking before them, but they did not see the heels of God's feet, as Psalm 77:19 says, "Your way was in the sea, and Your paths in the great waters, and Your footsteps were not known."[82]

.jpg)

The school of Rabbi Ishmael reasoned from the meaning of the word "in the midst" (בְּתוֹךְ, be-tokh) in Exodus 14:22 to resolve an apparent contradiction between two Biblical verses. Rabbi Zerika asked about an apparent contradiction of Scriptural passages in the presence of Rabbi Eleazar, or, according to another version, he asked in the name of Rabbi Eleazar. Exodus 24:18 says: "And Moses entered into the midst of the cloud," whereas Exodus 40:35 reads: "And Moses was not able to enter into the tent of meeting because the cloud abode thereon." The Gemara concluded that this teaches us that God took hold of Moses and brought him into the cloud. Alternatively, the school of Rabbi Ishmael taught in a Baraita that in Exodus 24:18, the word for "in the midst" (בְּתוֹךְ, be-tokh) appears, and it also appears in Exodus 14:22: "And the children of Israel went into the midst of the sea." Just as in Exodus 14:22, the word "in the midst" (בְּתוֹךְ, be-tokh) implies a path, as Exodus 14:22 says, "And the waters were a wall unto them," so here too in Exodus 24:18, there was a path (for Moses through the cloud).[83]

Rabbi Hama ben Hanina deduced from Exodus 1:10 that Pharaoh meant: "Come, let us outwit the Savior of Israel." Pharaoh concluded that the Egyptians should afflict the Israelites with water, because as indicated by Isaiah 54:9, God had sworn not to bring another flood to punish the world. The Egyptians failed to note that while God had sworn not to bring another flood on the whole world, God could still bring a flood on only one people. Alternatively, the Egyptians failed to note that they could fall into the waters, as indicated by the words of Exodus 14:27, "the Egyptians fled towards it." This all bore out what Rabbi Eleazar said: In the pot in which they cooked, they were themselves cooked — that is, with the punishment that the Egyptians intended for the Israelites, the Egyptians were themselves punished.[84]

Reading the words, "there remained not so much as one of them," in Exodus 14:28, Rabbi Judah taught that not even Pharaoh himself survived, as Exodus 15:4 says, "Pharaoh's chariots and his host has He cast into the sea." Rabbi Nehemiah, however, said that Pharaoh alone survived, teaching that Exodus 9:16 speaks of Pharaoh when it says, "But in very deed for this cause have I made you to stand." And some taught that later on Pharaoh went down and was drowned, as Exodus 15:19 says, "For the horses of Pharaoh went in with his chariots and with his horsemen into the sea."[85]

Rabbi Simon said that on the fourth day, the Israelites encamped by the edge of the sea. The Egyptians were floating like skin-bottles upon the surface of the waters, and a north wind cast them opposite the Israelites' camp. The Israelites saw the Egyptians and recognized them, saying that these were officials of Pharaoh's palace, and those were taskmasters. The Israelites recognized every one, as Exodus 14:30 says, "And Israel saw the Egyptians dead upon the sea shore."[86]

The Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael cited four reasons for why "Israel saw the Egyptians dead upon the sea-shore," as reported in Exodus 14:30: (1) so that the Israelites should not imagine that the Egyptians escaped the sea on the other side, (2) so that the Egyptians should not imagine that the Israelites were lost in the sea as the Egyptians had been, (3) so that the Israelites might take the Egyptians' spoils of silver, gold, precious stones, and pearls, and (4) so that the Israelites might recognize the Egyptians and reprove them.[87]

Rabbi Jose the Galilean reasoned that as the phrase "the finger of God" in Exodus 8:15 referred to 10 plagues, "the great hand" (translated "the great work") in Exodus 14:31 (in connection with the miracle of the Reed Sea) must refer to 50 plagues upon the Egyptians, and thus to a variety of cruel and strange deaths.[88]

.jpg)

Exodus chapter 15

Rabbis in the Talmud gave differing explanations of how, as Exodus 15:1 reports, the Israelites sang the song of Exodus 15:1–19 along with Moses.[89] Rabbi Akiva taught that Moses sang the entire song, and the Israelites respond after him with the leading word, as where an adult read the Hallel (Psalms 113–118) for a congregation and they responded after him with the leading word (or some say, with "Hallelujah"). According to this explanation, Moses sang, "I will sing to the Lord," and the Israelites responded, "I will sing to the Lord"; then Moses sang, "For He has triumphed gloriously," and the Israelites once again responded, "I will sing to the Lord." Rabbi Eliezer son of Rabbi Jose the Galilean taught that Moses sang the entire song, one verse at a time, and the Israelites respond after him by repeating the entire song, one verse at a time, as where a minor read the Hallel for a congregation and they repeated after the minor all that minor had said. According to this explanation, Moses sang, "I will sing to the Lord," and the Israelites responded, "I will sing to the Lord"; then Moses sang, "For He has triumphed gloriously," and the Israelites responded, "For He has triumphed gloriously." Rabbi Nehemiah taught that Moses sang the opening, the Israelites repeated the opening, and then Moses and the Israelites recited the balance together, as where a school-teacher recited the Shema in the Synagogue. The Gemara explained that each of the three interpreted Exodus 15:1: Rabbi Akiva held that the word "saying" in Exodus 15:1 refers to the first clause, "I will sing to the Lord," and that was the Israelites' only response. Rabbi Eliezer son of Rabbi Jose the Galilean held that "saying" refers to every clause of the song. And Rabbi Nehemiah held that "and spoke" indicates that they all sang together, and "saying" indicates that Moses began first.[90]

The Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael counted 10 songs in the Tanakh: (1) the one that the Israelites recited at the first Passover in Egypt, as Isaiah 30:29 says, "You shall have a song as in the night when a feast is hallowed"; (2) the Song of the Sea in Exodus 15; (3) the one that the Israelites sang at the well in the wilderness, as Numbers 21:17 reports, "Then sang Israel this song: 'Spring up, O well'"; (4) the one that Moses spoke in his last days, as Deuteronomy 31:30 reports, "Moses spoke in the ears of all the assembly of Israel the words of this song"; (5) the one that Joshua recited, as Joshua 10:12 reports, "Then spoke Joshua to the Lord in the day when the Lord delivered up the Amorites"; (6) the one that Deborah and Barak sang, as Judges 5:1 reports, "Then sang Deborah and Barak the son of Abinoam"; (7) the one that David spoke, as 2 Samuel 22:1 reports, "David spoke to the Lord the words of this song in the day that the Lord delivered him out of the hand of all his enemies, and out of the hand of Saul"; (8) the one that Solomon recited, as Psalm 30:1 reports, "a song at the Dedication of the House of David"; (9) the one that Jehoshaphat recited, as 2 Chronicles 20:21 reports: "when he had taken counsel with the people, he appointed them that should sing to the Lord, and praise in the beauty of holiness, as they went out before the army, and say, 'Give thanks to the Lord, for His mercy endures forever'"; and (10) the song that will be sung in the time to come, as Isaiah 42:10 says, "Sing to the Lord a new song, and His praise from the end of the earth," and Psalm 149:1 says, "Sing to the Lord a new song, and His praise in the assembly of the saints."[91]

Ben Avvai said that everything is judged according to the principle of measure for measure; just as the Egyptians were proud, and cast the male children into the river, so God cast the Egyptians into the sea, as Exodus 15:1 says, "I will sing to the Lord, for he has triumphed triumphantly; the horse and his rider has he thrown into the sea." (Ben Avvai read the double expression of "triumphing" in Exodus 15:1 to imply that just as the Egyptians triumphed over the Israelites by casting their children into the sea, so God triumphed over the Egyptians by casting them into the sea.)[92]

Rabbi Eliezer taught that the words of Exodus 15:2, "This is my God, and I will glorify Him," indicate that the lowliest servant-girl at the Red Sea perceived what the prophets Isaiah and Ezekiel had not, for she saw God. And as soon as the Israelites saw God, they recognized God, and they all sang, "This is my God, and I will glorify Him."[93]

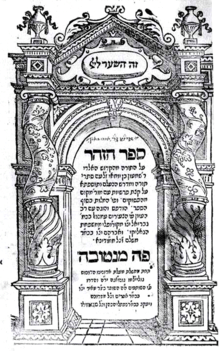

A Baraita taught that the words of Exodus 15:2, "This is my God, and I will adorn him," teach that one should adorn oneself before God in the fulfillment of the commandments. Thus, the Gemara taught that in God's honor, one should make a beautiful sukkah, a beautiful lulav, a beautiful shofar, beautiful tzitzit, and a beautiful Torah Scroll, and write it with fine ink, a fine reed pen, and a skilled penman, and wrap it about with beautiful silks. Abba Saul interpreted the word for "and I will glorify Him" (וְאַנְוֵהוּ, v'anveihu) in Exodus 15:2 to mean "and I will be like Him." Thus, Abba Saul reasoned, we should seek to be like God. Just as God is gracious and compassionate, so should we be gracious and compassionate.[94]

Reading the words of Exodus 15:2, "This is my God and I will praise Him, my father's God and I will exalt Him," Rabbi Jose the Galilean taught that even newborn and suckling children all saw God's Presence (שכינה, Shechinah) and praised God.[95] Rabbi Meir said that even fetuses in their mothers' wombs sang the song, as Psalm 68:27 says, "Bless the Lord in the Congregations, even the Lord, from the source of Israel." (And a person's "source" is the womb.) The Gemara asked how fetuses could see the Divine Presence. Rabbi Tanhum said that the abdomen of pregnant women became transparent and the fetuses saw.[96]

The Tosefta deduced from Exodus 1:22 that the Egyptians took pride before God only on account of the water of the Nile, and thus God exacted punishment from them only by water when in Exodus 15:4 God cast Pharaoh's chariots and army into the Reed Sea.[97]

Abba Hanan interpreted the words of Psalm 89:9, "Who is a mighty one like You, O God?" to teach: Who is like God, mighty in self-restraint, that God heard the blaspheming and insults of the wicked Titus and kept silent? In the school of Rabbi Ishmael it was taught that the words of Exodus 15:11, "Who is like You among the gods (אֵלִם, eilim)?" may be read to mean, "Who is like You among the mute (אִלְּמִים, illemim)?" (For in the face of Titus's blasphemy, God remained silent.)[98]

A Midrash taught that as God created the four cardinal directions, so also did God set about God's throne four angels — Michael, Gabriel, Uriel, and Raphael — with Michael at God's right. The Midrash taught that Michael got his name (Mi-ka'el, מִי-כָּאֵל) as a reward for the manner in which he praised God in two expressions that Moses employed. When the Israelites crossed the Red Sea, Moses began to chant, in the words of Exodus 15:11, "Who (mi, מִי) is like You, o Lord." And when Moses completed the Torah, he said, in the words of Deuteronomy 33:26, "There is none like God (ka'el, כָּאֵל), O Jeshurun." The Midrash taught that mi (מִי) combined with ka'el (כָּאֵל) to form the name Mi ka'el (מִי-כָּאֵל).[99]

Reading Exodus 15:11, the Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer taught that the Israelites said to God that there is none like God among the ministering angels, and therefore all the angels' names contain part of a Name for God (אֱלֹהִים, Elohim). For example, the names Michael and Gabriel contain the word אֱל, El.[100]

The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer taught that when in Exodus 15:11 the Israelites sang, "Who is like You among the divine creatures, O Lord?" Pharaoh replied after them, saying the concluding words of Exodus 15:11, "Who is like You, glorious in holiness, fearful in praises, doing wonders?" Rabbi Nechunia, son of Hakkanah, thus cited Pharaoh as an example of the power of repentance. Pharaoh rebelled most grievously against God, saying, as reported in Exodus 5:2, "Who is the Lord, that I should hearken to His voice?" But then Pharaoh repented using the same terms of speech with which he sinned, saying the words of Exodus 15:11, "Who is like You, O Lord, among the mighty?" God thus delivered Pharaoh from the dead. Rabbi Nechunia deduced that Pharaoh had died from Exodus 9:15, in which God told Moses to tell Pharaoh, "For now I had put forth my hand, and smitten you."[101]

The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer noted that Exodus 15:11 does not employ the words "fearful in praise," but "fearful in praises." For the ministering angels sing praises on high, and Israel sings praises on earth below. Thus Exodus 15:11 says, "fearful in praises, doing wonders," and Psalm 22:4 says, "You are holy, O You Who inhabit the praises of Israel."[100]

.jpg)

Rabbi Judah ben Simon expounded on God's words in Deuteronomy 32:20, "I will hide My face from them." Rabbi Judah ben Simon compared Israel to a king's son who went into the marketplace and struck people but was not struck in return (because of his being the king's son). He insulted but was not insulted. He went up to his father arrogantly. But the father asked the son whether he thought that he was respected on his own account, when the son was respected only on account of the respect that was due to the father. So the father renounced the son, and as a result, no one took any notice of him. So when Israel went out of Egypt, the fear of them fell upon all the nations, as Exodus 15:14–16 reported, "The peoples have heard, they tremble; pangs have taken hold on the inhabitants of Philistia. Then were the chiefs of Edom frightened; the mighty men of Moab, trembling takes hold upon them; all the inhabitants of Canaan are melted away. Terror and dread falls upon them." But when Israel transgressed and sinned, God asked Israel whether it thought that it was respected on its own account, when it was respected only on account of the respect that was due to God. So God turned away from them a little, and the Amalekites came and attacked Israel, as Exodus 17:8 reports, "Then Amalek came, and fought with Israel in Rephidim," and then the Canaanites came and fought with Israel, as Numbers 21:1 reports, "And the Canaanite, the king of Arad, who dwelt in the South, heard tell that Israel came by the way of Atharim; and he fought against Israel." God told the Israelites that they had no genuine faith, as Deuteronomy 32:20 says, "they are a very disobedient generation, children in whom is no faith." God concluded that the Israelites were rebellious, but to destroy them was impossible, to take them back to Egypt was impossible, and God could not change them for another people. So God concluded to chastise and try them with suffering.[102]

A Baraita taught that the words, "I will send My terror before you, and will discomfort all the people to whom you shall come, and I will make all your enemies turn their backs to you," in Exodus 23:27, and the words, "Terror and dread fall upon them," in Exodus 15:16 show that no creature was able to withstand the Israelites as they entered into the Promised Land in the days of Joshua, and those who stood against them were immediately panic-stricken and lost control of their bowels. And the words, "till Your people pass over, O Lord," in Exodus 15:16 allude to the first advance of the Israelites into the Promised Land in the days of Joshua. And the words, "till the people pass over whom You have gotten," in Exodus 15:16 allude to the second advance of the Israelites into the Promised Land in the days of Ezra. The Baraita thus concluded that the Israelites were worthy that God should perform a miracle on their behalf during the second advance as in the first advance, but that did not happen because the Israelites' sin caused God to withhold the miracle.[103]

The Gemara counted Exodus 15:18, "The Lord shall reign for ever and ever," among only three verses in the Torah that indisputably refer to God's Kingship, and thus are suitable for recitation on Rosh Hashanah. The Gemara also counted Numbers 23:21, "The Lord his God is with him, and the shouting for the King is among them"; and Deuteronomy 33:5, "And He was King in Jeshurun." Rabbi Jose also counted as Kingship verses Deuteronomy 6:4, "Hear, O Israel, the Lord our God the Lord is One"; Deuteronomy 4:39, "And you shall know on that day and lay it to your heart that the Lord is God, . . . there is none else"; and Deuteronomy 4:35, "To you it was shown, that you might know that the Lord is God, there is none else beside Him"; but Rabbi Judah said that none of these three is a Kingship verse. (The traditional Rosh Hashanah liturgy follows Rabbi Jose and recites Numbers 23:21, Deuteronomy 33:5, and Exodus 15:18, and then concludes with Deuteronomy 6:4.)[104]

The Gemara cited the language of Exodus 15:18, "The Lord shall reign for ever and ever," as a premier example of how Scripture indicates permanence. A Baraita taught at the school of Rabbi Eliezer ben Jacob said that wherever Scripture employs the expression נֶצַח, nezach; סֶלָה, selah; or וָעֶד, va'ed; the process to which it refers never ceases. The Gemara cited these proofs: Using נֶצַח, nezach, Isaiah 57:16 says, "For I will not contend for ever, neither will I be always (נֶצַח, nezach) angry." Using סֶלָה, selah, Psalm 48:9 says, "As we have heard, so have we seen in the city of the Lord of hosts, in the city of our God — God establish it forever. Selah." Using וָעֶד, va'ed, Exodus 15:18 says, "The Lord shall reign for ever and ever (לְעֹלָם וָעֶד, l'olam va'ed)."[105]

Rav Judah taught in Rav's name that the words of Deuteronomy 5:11 (5:12 in the NJPS), "Observe the Sabbath day . . . as the Lord your God commanded you" (in which Moses used the past tense for the word "commanded," indicating that God had commanded the Israelites to observe the Sabbath before the revelation at Mount Sinai) indicate that God commanded the Israelites to observe the Sabbath when they were at Marah, about which Exodus 15:25 reports, "There He made for them a statute and an ordinance."[106]

The Mishnah taught that all Jews have a portion in the world to come, for in Isaiah 60:21, God promises, "Your people are all righteous; they shall inherit the land for ever, the branch of My planting, the work of My hands, that I may be glorified.' But Rabbi Akiva warned that one who whispered Exodus 15:26 as an incantation over a wound to heal it would have no place in the world to come.[107]

The Gemara deduced from Exodus 15:26 that Torah study keeps away painful sufferings. Rabbi Shimon ben Lakish (Resh Lakish) deduced that painful sufferings keep away from one who studies the Torah from Job 5:7, which says, "And the sons of רֶשֶׁף, reshef, fly upward (עוּף, uf)." He argued that the word עוּף, uf, refers only to the Torah, as Proverbs 23:5 says, "Will you close (הֲתָעִיף, hataif) your eyes to it (the Torah)? It is gone." And רֶשֶׁף, reshef, refers only to painful sufferings, as Deuteronomy 32:24 says, "The wasting of hunger, and the devouring of the fiery bolt (רֶשֶׁף, reshef). Rabbi Johanan said to Rabbi Shimon ben Lakish that even school children know that the Torah protects against painful disease. For Exodus 15:26 says, "And He said: 'If you will diligently hearken to the voice of the Lord your God, and will do that which is right in His eyes, and will give ear to His commandments, and keep all His statutes, I will put none of the diseases upon you that I have put upon the Egyptians; for I am the Lord Who heals you." Rather one should say that God visits those who have the opportunity to study the Torah and do not do so with ugly and painful sufferings which stir them up. For Psalm 39:3 says, "I was dumb with silence, I kept silence from the good thing, and my pain was stirred up." "The good thing" refers only to the Torah, as Proverbs 4:2 says, "For I give you good doctrine; forsake not My teaching."[108]

Exodus chapter 16

The Gemara asked how one could reconcile Exodus 16:4, which reported that manna fell as "bread from heaven"; with Numbers 11:8, which reported that people "made cakes of it," implying that it required baking; and with Numbers 11:8, which reported that people "ground it in mills," implying that it required grinding. The Gemara concluded that the manna fell in different forms for different classes of people: For the righteous, it fell as bread; for average folk, it fell as cakes that required baking; and for the wicked, it fell as kernels that required grinding.[109] The Gemara asked how one could reconcile Exodus 16:31, which reported that "the taste of it was like wafers made with honey," with Numbers 11:8, which reported that "the taste of it was as the taste of a cake baked with oil." Rabbi Jose ben Hanina said that the manna tasted differently for different classes of people: It tasted like honey for infants, bread for youths, and oil for the aged.[110]

The Mishnah taught that the manna that Exodus 16:14–15 reports came down to the Israelites was among 10 miraculous things that God created on Sabbath eve at twilight on the first Friday at the completion of the Creation of the world.[111]

A Midrash read the words "but some of them left of it until the morning" in Exodus 16:20 to refer to the people who lacked faith. Rabbi Simeon ben Lakish (Resh Lakish) identified them with Dathan and Abiram, reasoning that Numbers 16:26 uses the word "men" to refer to Dathan and Abiram, and thus the word "men" in Exodus 16:20 must also refer to them.[112]

Reading the words "and it bred worms and rotted" in Exodus 16:20, a Midrash asked whether anything exists that first produces worms and then rots (implying that surely, rot precedes worms). Answering in the negative, the Midrash taught that God wished to reveal to people the deeds of those who disobeyed and saved the manna, so God caused many worms to breed during that night so that the sinners should not be able to smell the staleness of the manna in the evening and throw it out. The Midrash told that Moses became so angry with them that he forgot to tell them to gather two omers for each person on the sixth day. So when they went out and gathered on the sixth day and found a double portion, the princes told Moses, as Exodus 16:22 reports, "And all the rulers of the congregation came and told Moses." The Midrash noted that Moses told them (in Exodus 16:23), "This is that which the Lord has spoken," not "which I have spoken," because Moses had forgotten. For this reason, the Midrash taught, in Exodus 16:28, God asked, "How long will you refuse to keep My commandments and My laws?" including Moses among them (as Moses should not have given vent to his anger, thereby forgetting God's command).[113]

.jpg)

Tractate Shabbat in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of the Sabbath in Exodus 16:23 and 29; 20:7–10 (20:8–11 in the NJPS); 23:12; 31:13–17; 35:2–3; Leviticus 19:3; 23:3; Numbers 15:32–36; and Deuteronomy 5:11 (5:12 in the NJPS).[114]

Reading the words "See that the Lord has given you the Sabbath" in Exodus 16:29, a Midrash asked why it says "see" when "know" would have been better. The Midrash explained that God told them that when nonbelievers would come and question why the Israelites kept the Sabbath on the day that they did, the Israelites could tell the nonbelievers, "See, the manna does not descend on the Sabbath."[115]

The Alphabet of Rabbi Akiva taught that when God was giving Israel the Torah, God told them that if they accepted the Torah and observed God's commandments, then God would give them for eternity a most precious thing that God possessed — the World To Come. When Israel asked to see in this world an example of the World To Come, God replied that the Sabbath is an example of the World To Come.[116]

A Midrash asked to which commandment Deuteronomy 11:22 refers when it says, "For if you shall diligently keep all this commandment that I command you, to do it, to love the Lord your God, to walk in all His ways, and to cleave to Him, then will the Lord drive out all these nations from before you, and you shall dispossess nations greater and mightier than yourselves." Rabbi Levi said that "this commandment" refers to the recitation of the Shema (Deuteronomy 6:4–9), but the Rabbis said that it refers to the Sabbath, which is equal to all the precepts of the Torah.[117]

Tractate Eruvin in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of not walking beyond permitted limits in Exodus 16:29.[118]

A Baraita taught that Josiah hid away the jar of manna referred to in Exodus 16:33, the Ark referred to in Exodus 37:1–5, the anointing oil referred to in Exodus 30:22–33, Aaron's rod with its almonds and blossoms referred to in Numbers 17:23, and the coffer that the Philistines sent the Israelites as a gift along with the Ark and concerning which the priests said in 1 Samuel 6:8, "And put the jewels of gold, which you returned Him for a guilt offering, in a coffer by the side thereof [of the Ark]; and send it away that it may go." Having observed that Deuteronomy 28:36 predicted, "The Lord will bring you and your king . . . to a nation that you have not known," Josiah ordered the Ark hidden away, as 2 Chronicles 35:3 reports, "And he [Josiah] said to the Levites who taught all Israel, that were holy to the Lord, 'Put the Holy Ark into the house that Solomon the son of David, King of Israel, built; there shall no more be a burden upon your shoulders; now serve the Lord your God and his people Israel.'" Rabbi Eleazar deduced that Josiah hid the anointing oil and the other objects at the same time as the Ark from the common use of the expressions "there" in Exodus 16:33 with regard to the manna and "there" in Exodus 30:6 with regard to the Ark, "to be kept" in Exodus 16:33 with regard to the manna and "to be kept" in Numbers 17:25 with regard to Aaron's rod, and "generations" in Exodus 16:33 with regard to the manna and "generations" in Exodus 30:31 with regard to the anointing oil.[119]

Exodus chapter 17

In the Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael, Rabbi Eliezer said that the Israelites at Massah said that if God satisfied their needs, they would serve God, but if not, they would not serve God. Thus, Exodus 17:7 reports their "trying the Lord, saying: 'Is the Lord in our midst or not?'"[120]

The Mishnah reported that in synagogues at Purim, Jews read Exodus 17:8–16.[121]

A Midrash taught that wherever Scripture uses the word "men," Scripture implies righteous people, as in Exodus 17:9, "And Moses said to Joshua: 'Choose us out men'"; in 1 Samuel 17:12, "And the man was an old man (and thus wise) in the days of Saul, coming among men (who would naturally be like him)"; and in 1 Samuel 1:11, "But will give to Your handmaid seed who are men."[122]

The Mishnah quoted Exodus 17:11, which described how when Moses held up his hand, Israel prevailed, and asked whether Moses' hands really made war or stopped it. Rather, the Mishnah read the verse to teach that as long as the Israelites looked upward and submitted their hearts to God, they would grow stronger, but when they did not, they would fall. The Mishnah taught that the fiery serpent placed on a pole in Numbers 21:8 worked much the same way, by directing the Israelites to look upward to God.[123]

In medieval Jewish interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these medieval Jewish sources:[124]

Exodus chapter 14

Reading God's statement in Exodus 14:4, "I will harden Pharaoh's heart," and similar statements in Exodus 4:21; 7:3; 9:12; 10:1, 20, 27; 11:10; and 14:8 and 17, Maimonides concluded that it is possible for a person to commit such a great sin, or so many sins, that God decrees that the punishment for these willing and knowing acts is the removal of the privilege of repentance (תְשׁוּבָה, teshuvah). The offender would thus be prevented from doing repentance, and would not have the power to return from the offense, and the offender would die and be lost because of the offense. Maimonides read this to be what God said in Isaiah 6:10, "Make the heart of this people fat, and make their ears heavy, and their eyes weak, lest they see with their eyes and hear with their ears, and their hearts will understand, do repentance and be healed." Similarly 2 Chronicles 36:16 reports, "They ridiculed the messengers of God, disdained His words and insulted His prophets until the anger of God rose upon the people, without possibility of healing." Maimonides interpreted these verses to teach that they sinned willingly and to such an egregious extent that they deserved to have repentance withheld from them. And thus because Pharaoh sinned on his own at the beginning, harming the Jews who lived in his land, as Exodus 1:10 reports him scheming, "Let us deal craftily with them," God issued the judgment that repentance would be withheld from Pharaoh until he received his punishment, and therefore God said in Exodus 14:4, "I will harden the heart of Pharaoh." Maimonides explained that God sent Moses to tell Pharaoh to send out the Jews and do repentance, when God had already told Moses that Pharaoh would refuse, because God sought to inform humanity that when God withholds repentance from a sinner, the sinner will not be able to repent. Maimonides made clear that God did not decree that Pharaoh harm the Jewish people; rather, Pharaoh sinned willfully on his own, and he thus deserved to have the privilege of repentance withheld from him.[125]

Exodus chapter 17

Reading the account of Massah and Meribah in Exodus 17:1–7, Isaac Abravanel argued that if the Israelites lacked drinking water, then they were justified in complaining, and to whom should they have turned if not to their leader Moses? So Abravanel asked why Exodus 17:7 should term this conduct of theirs "trying," as it appeared to be an absolutely legitimate and essential request.[126]

In modern interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these modern sources:

Exodus chapter 13

Moshe Greenberg of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem wrote that one may see the entire Exodus story as "the movement of the fiery manifestation of the divine presence."[127] Similarly, Professor William Propp of the University of California, San Diego, identified fire (אֵשׁ, esh) as the medium in which God appears on the terrestrial plane — in the Burning Bush of Exodus 3:2, the cloud pillar of Exodus 13:21–22 and 14:24, atop Mount Sinai in Exodus 19:18 and 24:17, and upon the Tabernacle in Exodus 40:38.[128]

Exodus chapter 14

Noting that Ezekiel 29:3 addresses the Pharaoh as a "mighty monster (הַתַּנִּים הַגָּדוֹל, ha-tanim ha-gadol)," thus associating him with the primeval sea monster that Psalm 74:13–14 reports God defeated in establishing order and creating the world, Rabbi Shai Held of Yeshivat Hadar argued that the Bible thematically associates Pharaoh with the forces of chaos, and thus that God's vanquishing Pharaoh at the sea in Exodus 14–15 reenacts God's primordial victory over the sea monster and chaos in creating the world.[129]

Professor Everett Fox of Clark University noted that "glory" (כְּבוֹד, kevod) and "stubbornness" (כָּבֵד לֵב, kaved lev) are leading words throughout the book of Exodus that give it a sense of unity.[130] Similarly, Propp identified the root kvd — connoting heaviness, glory, wealth, and firmness — as a recurring theme in Exodus: Moses suffered from a heavy mouth in Exodus 4:10 and heavy arms in Exodus 17:12; Pharaoh had firmness of heart in Exodus 7:14; 8:11, 28; 9:7, 34; and 10:1; Pharaoh made Israel's labor heavy in Exodus 5:9; God in response sent heavy plagues in Exodus 8:20; 9:3, 18, 24; and 10:14, so that God might be glorified over Pharaoh in Exodus 14:4, 17, and 18; and the book culminates with the descent of God's fiery Glory, described as a "heavy cloud," first upon Sinai and later upon the Tabernacle in Exodus 19:16; 24:16–17; 29:43; 33:18, 22; and 40:34–38.[128]

In his digest of Christopher Columbus's log from Columbus's first voyage, the 16th-century Spanish historian Bartolomé de las Casas reported that on Sunday, September 23, 1492, the sea was calm and smooth, causing the crew to grumble, saying that since there were no heavy seas in those parts, no wind would ever carry them back to Spain. But later, to their astonishment, the seas rose high without any wind. Referring to the splitting of the sea in Exodus 14, Columbus then said, "I was in great need of these high seas because nothing like this had occurred since the time of the Jews when the Egyptians came out against Moses who was leading them out of captivity."[131]

In a March 1776 sermon, Massachusetts minister Elijah Fitch likened the British King George III to "that proud and haughty Monarch Pharaoh, king of Egypt." Fitch argued that God appeared to aid the Israelites when they shook off the yoke of Egyptian bondage, and Pharaoh and his host pursued them and seemed to leave them no way of escape, and so God would aid the colonists. Fitch said that God permits the wicked to accomplish some of their evil purposes against the just, but in the end frustrates them. And "thus was it with proud Pharaoh, he was lifted up on high, with sure expectations of destroying the Israelites and dividing the spoil, flushed with the hopes of certain success, he rushes forward, till his glory, his pomp and his multitude are altogether buried in the sea."[132]

Similarly, the Massachusetts minister Phillips Payson preached of the American Revolution that "the finger of God has indeed been so conspicuous in every stage of our glorious struggle, that it seems as if the wonders and miracles performed for Israel of old, were repeated anew for the American Israel, in our day." Payson also likened George III to pharaoh, saying: "The hardness that possessed the heart of Pharaoh of old, seems to have calloused the heart of the British King; and the madness that drove that ancient tyrant and his hosts into the sea, appears to have possessed the British court and councils."[133]

In 1776, Benjamin Franklin proposed a Great Seal of the United States based on Exodus 14, with "Moses lifting up his Wand, and dividing the Red Sea, and Pharaoh, in his Chariot overwhelmed with the Waters."[134]

The 19th century pre-Civil War African-American spiritual "Mary Don't You Weep" employed the image of Moses at the shore of the sea and the liberation of the Israelites in the context of slavery in the United States.[135]

The 18th-century German Jewish philosopher Moses Mendelssohn read the report of Exodus 14:31 that "the Israelites saw and trusted in the Eternal and in Moses, his servant" along with the report of Genesis 15:6 that "Abraham trusted in the Eternal" to demonstrate that the word often translated as "faith" actually means, in most cases, "trust," "confidence," and "firm reliance." Thus Mendelssohn concluded that Scripture does not command faith, but accepts no other commands than those that come by way of conviction. Its propositions are presented to the understanding, submitted for consideration, without being forced upon our belief. Belief and doubt, assent and opposition, in Mendelssohn's view, are not determined by desire, wishes, longings, fear, or hope, but by knowledge of truth and untruth. Hence, Mendelssohn concluded, ancient Judaism has no articles of faith.[136]

Exodus chapter 15

Professor James Kugel of Bar Ilan University wrote that scholars have established that Semitic languages did not originally have a definite article (corresponding to the word "the" in English), but later developed one (the prefix הַ, ha, in Hebrew). That the song of Exodus 15:1–19 does not contain even one definite article indicated to Kugel (along with other ancient morphological and lexical features) that "it has been preserved from a very early stage of the Hebrew language and thus may be one of the oldest parts of the Bible."[137]

Similarly, Professor Robert A. Oden, formerly of Dartmouth College, called Exodus 15 "almost certainly the oldest single extended poem in the Hebrew Bible," describing "the parade holy war events, the Exodus from Egypt and the conquest of the land of Canaan." Oden compared the holy war poem of Exodus 15, which follows a prose version of the same event in Exodus 14, to Judges 5, which follows a prose version of the same event in Judges 4, arguing that both poems were already difficult to understand at the time that editors assembled the Hebrew Bible. Oden grouped Exodus 15 along with Judges 5, Habakkuk 3, and Psalm 68 as exemplars of holy war hymns that revealed the religion of the Tribal League that preceded the formation of Israel.[138]

Similarly, Propp considered it likely that the Song of the Sea (Exodus 15:1b–18HE) originally circulated independently and should thus be considered another source.[139]

Professor Walter Brueggemann, formerly of Columbia Theological Seminary, suggested a chiastic structure to the song of Exodus 15:1–19 as follows:[140]

- A: The introduction announces the core theme. (Exodus 15:1–3.)

- B: The first core element, a victory song (Exodus 15:4–10.)

- C: A doxology affirms God's distinctiveness. (Exodus 15:11–12.)

- B1: The second core element, a triumphal procession of the Victor to the throne. (Exodus 15:13–17.)

- B: The first core element, a victory song (Exodus 15:4–10.)

- A1: The conclusion, an enthronement formula anticipating God's reign (Exodus 15:18.)

In Exodus 15:11, "Who is like you among the gods, O Lord?" Professor John J. Collins of Yale Divinity School found continuity with the Mesopotamian view of divinity that freely granted the reality of other gods.[141]

Exodus chapter 16

In 1950, the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of Conservative Judaism ruled: "Refraining from the use of a motor vehicle is an important aid in the maintenance of the Sabbath spirit of repose. Such restraint aids, moreover, in keeping the members of the family together on the Sabbath. However where a family resides beyond reasonable walking distance from the synagogue, the use of a motor vehicle for the purpose of synagogue attendance shall in no way be construed as a violation of the Sabbath but, on the contrary, such attendance shall be deemed an expression of loyalty to our faith. . . . [I]n the spirit of a living and developing Halachah responsive to the changing needs of our people, we declare it to be permitted to use electric lights on the Sabbath for the purpose of enhancing the enjoyment of the Sabbath, or reducing personal discomfort in the performance of a mitzvah."[142]

Spinoza taught that religion only acquires the force of law by means of a sovereign power. Therefore, Moses was not able to punish those who, before the covenant, and consequently while still in possession of their rights, violated the Sabbath (in Exodus 16:27). However, Moses was able to do so after the covenant (in Numbers 15:36), because all the Israelites had then yielded up their natural rights, and the ordinance of the Sabbath had received the force of law.[143]

Exodus chapter 17

The 20th century Israeli scholar Nehama Leibowitz argued that the sin with which the Israelites were charged at Massah was that of trying to find out whether belief in God was worthwhile. Leibowitz said that the Israelites did not really need to ask if God was among them or not, for surely they had by then plainly benefitted from God's kindnesses on more than one occasion.[144]

Commandments

According to Maimonides and Sefer ha-Chinuch, there is one negative commandment in the parashah:[145]

- Not to walk outside permitted limits on the Sabbath.[146]

In the liturgy

The concluding blessing of the Shema, immediately prior to the Amidah prayer in each of the three prayer services recounts events from Exodus 14:21–31.[147]

The Passover Haggadah, in the magid section of the Seder, recounts the reasoning of Rabbi Jose the Galilean that as the phrase "the finger of God" in Exodus 8:15 referred to 10 plagues, "the great hand" (translated "the great work") in Exodus 14:31 must refer to 50 plagues upon the Egyptians.[148]

The Song of the Sea, Exodus 15:1–18, appears in its entirety in the P'sukei D'zimra section of the morning service for Shabbat[149]

The references to God's mighty hand and arm in Exodus 15:6, 12, and 16 are reflected in Psalm 98:1, which is also one of the six Psalms recited at the beginning of the Kabbalat Shabbat prayer service.[150]

The statement of God's eternal sovereignty in Exodus 15:18, "God will reign for ever and ever!" may have found paraphrase in Psalm 146:10, "Adonai shall reign throughout all generations," which in turn appears in the Kedushah section of the Amidah prayer in each of the three Jewish services/prayer services. And the statement of God's eternal sovereignty in Exodus 15:18 also appears verbatim in the Kedushah D'Sidra section of the Minchah service for Shabbat.[151]

The people's murmuring at Massah and Meribah, and perhaps the rock that yielded water, of Exodus 17:2–7 are reflected in Psalm 95, which is in turn the first of the six Psalms recited at the beginning of the Kabbalat Shabbat prayer service.[152]

The Weekly Maqam

In the Weekly Maqam, Sephardi Jews each week base the songs of the services on the content of that week's parashah. For Parashat Beshalach, Sephardi Jews apply Maqam Ajam, which commemorates the joy and song of the Israelites as they crossed the sea.[153]

Haftarah

The haftarah for the parashah is:

- for Ashkenazi Jews: Judges 4:4–5:31; and

- for Sephardi Jews: Judges 5:1–31.

For Ashkenazi Jews, the haftarah is the longest of the year.

Both the parashah and the haftarah contain songs that celebrate the victory of God's people, the parashah in the "Song of the Sea" about God's deliverance of the Israelites from Pharaoh,[154] and the haftarah in the "Song of Deborah" about the Israelites' victory over the Canaanite general Sisera.[155] Both the parashah and the haftarah report how the leaders of Israel's enemies assembled hundreds of chariots.[156] Both the parashah and the haftarah report how God "threw . . . into panic" (va-yaham) Israel's enemies.[157] Both the parashah and the haftarah report waters sweeping away Israel's enemies.[158] Both the parashah and the haftarah report singing by women to celebrate, the parashah by Miriam,[159] and the haftarah by Deborah.[155] Finally, both the parashah and the haftarah mention Amalek.[160]

The Gemara tied together God's actions in the parashah and the haftarah. To reassure Israelites concerned that their enemies still lived, God had the Reed Sea spit out the dead Egyptians.[161] To repay the seas, God committed the Kishon River to deliver one-and-a-half times as many bodies. To pay the debt, when Sisera came to attack the Israelites, God had the Kishon wash the Canaanites away.[162] The Gemara calculated one-and-a-half times as many bodies from the numbers of chariots reported in Exodus 14:7 and Judges 4:13.[163]

Notes

- "Torah Stats — Shemoth". Akhlah Inc. Retrieved March 30, 2013.

- "Parashat Beshalach". Hebcal. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- Esther 1:1–10:3.

- Seder Eliyahu Rabbah, chapter 20. Targum Sheni to Esther 4:13.

- See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Shemos/Exodus. Edited by Menachem Davis, pages 88–119. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2008. ISBN 1-4226-0204-4.

- Exodus 13:17–18.

- Exodus 13:19.

- Exodus 13:21–22.

- See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Shemos/Exodus. Edited by Menachem Davis, page 90.

- Exodus 14:1–4.

- Exodus 14:5–8.

- See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Shemos/Exodus. Edited by Menachem Davis, page 92.

- Exodus 14:9.

- Exodus 14:10–12.

- Exodus 14:13–14.

- See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Shemos/Exodus. Edited by Menachem Davis, page 94.

- Exodus 14:15–16.

- Exodus 14:21–22.

- Exodus 14:23–25.

- See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Shemos/Exodus. Edited by Menachem Davis, page 97.

- Exodus 14:26–28.

- Exodus 15:1–21.

- See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Shemos/Exodus. Edited by Menachem Davis, page 105.

- Exodus 15:22.

- Exodus 15:23–24.

- Exodus 15:25.

- Exodus 15:26.

- See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Shemos/Exodus. Edited by Menachem Davis, page 107.

- Exodus 15:27–16:3.

- See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Shemos/Exodus. Edited by Menachem Davis, page 108.

- Exodus 16:4–5.

- Exodus 16:5–10.

- See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Shemos/Exodus. Edited by Menachem Davis, page 110.

- Exodus 16:11–14.

- Exodus 16:15–18.

- Exodus 16:19–20.

- Exodus 16:22–24.

- Exodus 16:25–27.

- See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Shemos/Exodus. Edited by Menachem Davis, page 114.

- Exodus 16:32–33.

- Exodus 16:35.

- See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Shemos/Exodus. Edited by Menachem Davis, page 115.

- Exodus 17:1–2.

- Exodus 17:5–7.

- See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Shemos/Exodus. Edited by Menachem Davis, page 117.

- Exodus 17:8.

- Exodus 17:9–11.

- Exodus 17:12–13.

- See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Shemos/Exodus. Edited by Menachem Davis, page 119.

- Exodus 17:14.

- See, e.g., Richard Eisenberg "A Complete Triennial Cycle for Reading the Torah." Proceedings of the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Movement: 1986–1990, pages 383–418. New York: The Rabbinical Assembly, 2001. ISBN 0-91-6219-18-6.

- For more on inner-Biblical interpretation, see, e.g., Benjamin D. Sommer, "Inner-biblical Interpretation," in The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition, edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), pages 1835–41.

- The Sabbath Anthology. Edited by Abraham E. Millgram (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1944; reprinted 2018), page 203.

- Exodus 20:8–11 in the NJPS.

- Deuteronomy 5:12–15 in the NJPS.

- For more on early nonrabbinic interpretation, see, e.g., Esther Eshel, "Early Nonrabbinic Interpretation," in The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition, edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, pages 1841–59.

- I Maccabees, translated by Jonathan A. Goldstein (New York: Doubleday and Company, 1976), pages 5, 234–35.

- For more on classical rabbinic interpretation, see, e.g., Yaakov Elman, "Classical Rabbinic Interpretation," in The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition, edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, pages 1859–78.

- Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael Beshallah 19:1:5 (Land of Israel, late 4th century); eprinted in, e.g., Mekhilta According to Rabbi Ishmael, translated by Jacob Neusner (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1988); and Mekhilta de-Rabbi Ishmael, translated by Jacob Z. Lauterbach (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1933, reissued 2004).

- Exodus Rabbah 20:17. 10th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Exodus. Translated by Simon M. Lehrman, volume 3, page 256. London: Soncino Press, 1939. ISBN 0-900689-38-2.

- Genesis Rabbah 54:2. Land of Israel, 5th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Genesis. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 1, pages 476–77. London: Soncino Press, 1939. ISBN 0-900689-38-2.

- Megillah 31a. Babylonia, 6th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Taanit • Megillah. Commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 12, page 405. Jerusalem: Koren Publishers, 2014. ISBN 978-965-301-573-9.

- Numbers Rabbah 1:2. 12th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5, pages 2–3. London: Soncino Press, 1939. ISBN 0-900689-38-2. See also Exodus Rabbah 25:7. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Exodus. Translated by Simon M. Lehrman, volume 3, pages 307–08. (making a similar playful reading of וַיַּסֵּב, vayaseiv).