Tazria

Tazria, Thazria, Thazri'a, Sazria, or Ki Tazria' (תַזְרִיעַ — Hebrew for "she conceives", the 13th word, and the first distinctive word, in the parashah) is the 27th weekly Torah portion (פָּרָשָׁה, parashah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the fourth in the Book of Leviticus. The parashah deals with ritual impurity. It constitutes Leviticus 12:1–13:59. The parashah is made up of 3,667 Hebrew letters, 1,010 Hebrew words, 67 verses, and 128 lines in a Torah Scroll (סֵפֶר תּוֹרָה, Sefer Torah).[1]

Jews read it the 27th or 28th Sabbath after Simchat Torah, generally in April or, rarely, in late March or early May. The lunisolar Hebrew calendar contains up to 55 weeks, the exact number varying between 50 in common years and 54 or 55 in leap years. In leap years (for example, 2019, 2022, 2024, and 2027), parashah Tazria is read separately. In common years (for example, 2018, 2020, 2021, 2023, 2025, 2026, and 2028), parashah Tazria is combined with the next parashah, Metzora, to help achieve the number of weekly readings needed.[2]

Readings

In traditional Sabbath Torah reading, the parashah is divided into seven readings, or עליות, aliyot.[3]

First reading — Leviticus 12:1–13:5

In the first reading (עליה, aliyah), God told Moses to tell the Israelites that when a woman at childbirth bore a boy, she was to be unclean 7 days and then remain in a state of blood purification for 33 days, while if she bore a girl, she was to be unclean 14 days and then remain in a state of blood purification for 66 days.[4] Upon completing her period of purification, she was to bring a lamb for a burnt offering and a pigeon or a turtle dove for a sin offering, and the priest was to offer them as sacrifices to make expiation on her behalf.[5] If she could not afford a sheep, she was to take two turtle doves or two pigeons, one for a burnt offering and the other for a sin offering.[6] God told Moses and Aaron that when a person had a swelling, rash, discoloration, scaly affection, inflammation, or burn, it was to be reported to the priest, who was to examine it to determine whether the person was clean or unclean.[7]

Second reading — Leviticus 13:6–17

In the second reading (עליה, aliyah), the priest was to examine the person again the seventh day to determine whether the person was clean or unclean.[8] The reading goes on to describe the features of skin disease.[9]

Third reading — Leviticus 13:18–23

The third reading (עליה, aliyah) further describes features of skin disease.[10]

Fourth reading — Leviticus 13:24–28

The fourth reading (עליה, aliyah) further describes features of skin disease.[11]

Fifth reading — Leviticus 13:29–39

The fifth reading (עליה, aliyah) describes features of skin disease on the head or beard.[12]

Sixth reading — Leviticus 13:40–54

The sixth reading (עליה, aliyah) continued the discussion of skin disease on the head or beard.[13] Unclean persons were to rend their clothes, leave their head bare, cover over their upper lips, call out, "Unclean! Unclean!" and dwell outside the camp.[14] When a streaky green or red eruptive affection occurred in wool, linen, or animal skin, it was to be shown to the priest, who was to examine to determine whether it was clean or unclean.[15] If unclean, it was to be burned.[16]

Seventh reading — Leviticus 13:55–59

In the seventh reading (עליה, aliyah), if the affection disappeared from the article upon washing, it was to be shut up seven days, washed again, and be clean.[17]

In inner-biblical interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these Biblical sources:[18]

Leviticus chapter 12

Leviticus 12 associates childbirth with uncleanness. In the Hebrew Bible, uncleanness has a variety of associations. Leviticus 11:8, 11; 21:1–4, 11; and Numbers 6:6–7; and 19:11–16; associate it with death. And perhaps similarly, Leviticus 13–14 associates it with skin disease. Leviticus 15 associates it with various sexuality-related events. And Jeremiah 2:7, 23; 3:2; 7:30; and Hosea 6:10 associate it with contact with the worship of alien gods.

While Leviticus 12:6–8 required a new mother to bring a burnt-offering and a sin-offering, Leviticus 26:9, Deuteronomy 28:11, and Psalm 127:3–5 make clear that having children is a blessing from God; Genesis 15:2 and 1 Samuel 1:5–11 characterize childlessness as a misfortune; and Leviticus 20:20 and Deuteronomy 28:18 threaten childlessness as a punishment.

Leviticus chapter 13

The Hebrew Bible reports skin disease (צָּרַעַת, tzara'at) and a person affected by skin disease (metzora, מְּצֹרָע) at several places, often (and sometimes incorrectly) translated as "leprosy" and "a leper." In Exodus 4:6, to help Moses to convince others that God had sent him, God instructed Moses to put his hand into his bosom, and when he took it out, his hand was "leprous (m'tzora'at, מְצֹרַעַת), as white as snow." In Leviticus 13–14, the Torah sets out regulations for skin disease (צָּרַעַת, tzara'at) and a person affected by skin disease (metzora, מְּצֹרָע). In Numbers 12:10, after Miriam spoke against Moses, God's cloud removed from the Tent of Meeting and "Miriam was leprous (m'tzora'at, מְצֹרַעַת), as white as snow." In Deuteronomy 24:8–9, Moses warned the Israelites in the case of skin disease (צָּרַעַת, tzara'at) diligently to observe all that the priests would teach them, remembering what God did to Miriam. In 2 Kings 5:1–19, part of the haftarah for parashah Tazria, the prophet Elisha cures Naaman, the commander of the army of the king of Aram, who was a "leper" (metzora, מְּצֹרָע). In 2 Kings 7:3–20, part of the haftarah for parashah Metzora, the story is told of four "leprous men" (m'tzora'im, מְצֹרָעִים) at the gate during the Arameans' siege of Samaria. And in 2 Chronicles 26:19, after King Uzziah tried to burn incense in the Temple in Jerusalem, "leprosy (צָּרַעַת, tzara'at) broke forth on his forehead".

In early nonrabbinic interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these early nonrabbinic sources:[19]

Leviticus chapter 13

Philo taught that the skin disease in Leviticus 13 signified voluntary depravity.[20]

In classical rabbinic interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these rabbinic sources from the era of the Mishnah and the Talmud:[21]

Leviticus chapter 12

Rabbi Simlai noted that just as God created humans after creating cattle, beasts, and birds, the law concerning human impurity in Leviticus 12 follows that concerning cattle, beasts, and birds in Leviticus 11.[22]

Reading Leviticus 12:2, “If a woman conceives,” Rabbi Levi said three things: It is only natural that if a person has given into another’s keeping an ounce of silver in private, and the latter returns a pound of gold in public, the former will surely be grateful to the latter; and so is it with God. Human beings entrust to God a drop of fluid in privacy, and God openly returns to them completed and perfected human beings. Rabbi Levi said a second thing: It is natural that, if a person is confined without attention to a chamber, and someone comes and kindles a light for the person there, the former should feel gratitude towards the latter. So too is it with God. When the embryo is in its mother’s womb, God causes a light to shine for it there with which it can see from one end of the world to the other. Rabbi Levi said a third thing: It is natural that, if a person is confined without attention to a chamber, and someone comes and releases the person and takes the person out from there, the former should feel gratitude to the latter. Even so when the embryo is in its mother’s womb, God comes and releases it and brings it forth into the world.[23]

Rabbi Ammi taught in the name of Rabbi Johanan that even though Rabbi Simeon ruled that a dissolved fetus expelled by a woman was not unclean, Rabbi Simeon nonetheless agreed that the woman was ritually unclean as a woman who bore a child. An old man explained to Rabbi Ammi that Rabbi Johanan reasoned from the words of Leviticus 12:2, "If a woman conceived seed and bore." Those words imply that even if a woman bore something like "conceived seed" (in a fluid state), she was nonetheless unclean by reason of childbirth.[24]

Rabbi Johanan interpreted the words "in the [eighth] day" in Leviticus 12:3 to teach that one must perform circumcision even on the Sabbath.[25]

The Gemara read the command of Genesis 17:14 to require an uncircumcised adult man to become circumcised, and the Gemara read the command of Leviticus 12:3 to require the father to circumcise his infant child.[26]

The Mishnah taught that circumcision should not be performed until the sun has risen, but counts it as done if done after dawn has appeared.[27] The Gemara explained that the reason for the rule could be found in the words of Leviticus 12:3, "And in the eighth day the flesh of his foreskin shall be circumcised".[28] A Baraita interpreted Leviticus 12:3 to teach that the whole eighth day is valid for circumcision, but deduced from Abraham's rising "early in the morning" to perform his obligations in Genesis 22:3 that the zealous perform circumcisions early in the morning.[29]

The disciples of Rabbi Simeon ben Yohai asked him why Leviticus 12:6–8 ordained that after childbirth a woman had to bring a sacrifice. He replied that when she bore her child, she swore impetuously in the pain of childbirth that she would never again have intercourse with her husband. The Torah, therefore, ordained that she had to bring a sacrifice, as she would probably violate that oath.[30] Rabbi Berekiah and Rabbi Simon said in the name of Rabbi Simeon ben Yohai that because she fluttered in her heart, she had to bring a fluttering sacrifice, two turtle-doves or two young pigeons.[31] The disciples asked Rabbi Simeon ben Yohai why Leviticus 12:2 permitted contact between the father and mother after 7 days when the mother bore a boy, but Leviticus 12:5 permitted contact after 14 days when she bore a girl. He replied that since everyone around the mother would rejoice upon the birth of a boy, she would regret her oath to shun her husband after just 7 days, but since people around her would not rejoice on the birth of a girl, she would take twice as long. And Rabbi Simeon ben Yohai taught that Leviticus 12:3 ordained circumcision on the eighth day so that the parents could join their guests in a celebratory mood on that day.[30]

Leviticus 5:7; 5:11; 12:8; and 14:21–22 provided that people of lesser means could bring less-expensive offerings. The Mishnah taught that one who sacrificed much and one who sacrificed little attained equal merit, so long as they directed their hearts to Heaven.[32] Rabbi Zera taught that Ecclesiastes 5:11 provided a Scriptural proof for this when it says, "Sweet is the sleep of a serving man, whether he eat little or much." Rav Adda bar Ahavah taught that Ecclesiastes 5:10 provided a Scriptural proof for this when it says, "When goods increase, they are increased who eat them; and what advantage is there to the owner thereof." Rabbi Simeon ben Azzai taught that Scripture says of a large ox, "An offering made by fire of a sweet savor"; of a small bird, "An offering made by fire of a sweet savor"; and of a meal-offering, "An offering made by fire of a sweet savor." Rabbi Simeon ben Azzai thus taught that Scripture uses the same expression each time to teach that it is the same whether people offered much or little, so long as they directed their hearts to Heaven.[33] And Rabbi Isaac asked why the meal-offering was distinguished in that Leviticus 2:1 uses the word "soul" (נֶפֶשׁ, nefesh) to refer to the donor of a meal-offering, instead of the usual "man" (אָדָם, adam, in Leviticus 1:2, or אִישׁ, ish, in Leviticus 7:8) used in connection with other sacrifices. Rabbi Isaac taught that Leviticus 2:1 uses the word "soul" (נֶפֶשׁ, nefesh) because God noted that the one who usually brought a meal-offering was a poor man, and God accounted it as if the poor man had offered his own soul.[34]

Rabbi Simeon noted that Scripture always lists turtledoves before pigeons, and imagined that one might thus think that Scripture prefers turtledoves over pigeons. But Rabbi Simeon quoted the instructions of Leviticus 12:8, "a young pigeon or a turtledove for a sin-offering", to teach that Scripture accepted both equally.[35]

Rabbi Eleazar ben Hisma taught that even the apparently arcane laws of bird offerings in Leviticus 12:8 and the beginning of menstrual cycles in Leviticus 12:1–8 are essential laws.[36]

Tractate Kinnim in the Mishnah interpreted the laws of pairs of sacrificial pigeons and doves in Leviticus 1:14, 5:7, 12:6–8, 14:22, and 15:29; and Numbers 6:10.[37]

Interpreting the beginning of menstrual cycles, as in Leviticus 12:6–8, the Mishnah ruled that if a woman loses track of her menstrual cycle, there is no return to the beginning of the niddah count in fewer than seven, nor more than seventeen days.[38]

The Mishnah (following Leviticus 5:7–8) taught that a sin-offering of a bird preceded a burnt-offering of a bird; and the priest also dedicated them in that order.[39] Rabbi Eliezer taught that wherever an offerer (because of poverty) substituted for an animal sin-offering the offering of two birds (one of which was for a sin-offering and the other for a burnt-offering), the priest sacrificed the bird sin-offering before the bird burnt-offering (as Leviticus 5:7–8 instructs). But in the case of a woman after childbirth discussed in Leviticus 12:8 (where a poor new mother could substitute for an animal burnt-offering two birds, one for a sin-offering and the other for a burnt-offering), the bird burnt-offering took precedence over the bird sin-offering. Wherever the offering came on account of sin, the sin-offering took precedence. But here (in the case of a woman after childbirth, where the sin-offering was not on account of sin) the burnt-offering took precedence. And wherever both birds came instead of one animal sin-offering, the sin-offering took precedence. But here (in the case of a woman after childbirth) they did not both come on account of a sin-offering (for in poverty she substituted a bird burnt-offering for an animal burnt-offering, as Leviticus 12:6–7 required her to bring a bird sin-offering in any case), the burnt-offering took precedence. (The Gemara asked whether this contradicted the Mishnah, which taught that a bird sin-offering took precedence over an animal burnt-offering, whereas here she brought the animal burnt-offering before the bird sin-offering.) Rava taught that Leviticus 12:6–7 merely accorded the bird burnt-offering precedence in the mentioning. (Thus, some read Rava to teach that Leviticus 12:6–8 lets the reader read first about the burnt-offering, but in fact the priest sacrificed the sin-offering first. Others read Rava to teach that one first dedicated the animal or bird for the burnt-offering and then dedicated the bird for the sin-offering, but in fact the priest sacrificed the sin-offering first.)[40]

Leviticus 12:8 called for "two turtle-doves, or two young pigeons: the one for a burnt-offering, and the other for a sin-offering". Rav Hisda taught that the designation of one of the birds to become the burnt-offering and the other to become the sin-offering was made either by the owner or by the priest's action. Rabbi Shimi bar Ashi explained that the words of Leviticus 12:8, "she shall take . . . the one for a burnt-offering, and the other for a sin-offering", indicated that the mother could have made the designation when taking the birds, and the words of Leviticus 15:15, "the priest shall offer them, the one for a sin-offering, and the other for a burnt-offering", and of Leviticus 15:30, "the priest shall offer the one for a sin-offering, and the other for a burnt-offering", indicated that (absent such a designation by the mother) the priest could have made the designation when offering them up.[41]

Leviticus chapter 13

Reading Leviticus 13:1, a Midrash taught that in 18 verses, Scripture places Moses and Aaron (the instruments of Israel’s deliverance) on an equal footing (reporting that God spoke to both of them alike),[42] and thus there are 18 benedictions in the Amidah.[43]

Tractate Negaim in the Mishnah and Tosefta interpreted the laws of skin disease in Leviticus 13.[44]

A Midrash compared the discussion of skin diseases beginning at Leviticus 13:2 to the case of a noble lady who, upon entering the king's palace, was terrified by the whips that she saw hanging about. But the king told her: "Do not fear; these are meant for the slaves, but you are here to eat, drink, and make merry." So, too, when the Israelites heard the section of Scripture dealing with leprous affections, they became afraid. But Moses told them: "These are meant for the wicked nations, but you are intended to eat, drink, and be joyful, as it is written in Psalm 32:10: "Many are the sufferings of the wicked; but he that trusts in the Lord, mercy surrounds him."[45]

Rabbi Johanan said in the name of Rabbi Joseph ben Zimra that anyone who bears evil tales (לשון הרע, lashon hara) will be visited by the plague of skin disease (צָּרַעַת, tzara'at), as it is said in Psalm 101:5: "Whoever slanders his neighbor in secret, him will I destroy (azmit)." The Gemara read azmit to allude to צָּרַעַת, tzara'at, and cited how Leviticus 25:23 says "in perpetuity" (la-zemitut). And Resh Lakish interpreted the words of Leviticus 14:2, "This shall be the law of the person with skin disease (metzora)," to mean, "This shall be the law for him who brings up an evil name (motzi shem ra)." And the Gemara reported that in the Land of Israel they taught that slander kills three persons: the slanderer, the one who accepts it, and the one about whom the slander is told.[46]

Similarly, Rabbi Haninah taught that skin disease came only from slander. The Rabbis found a proof for this from the case of Miriam, arguing that because she uttered slander against Moses, plagues attacked her. And the Rabbis read Deuteronomy 24:8–9 to support this when it says in connection with skin disease, "remember what the Lord your God did to Miriam".[47]

Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani said in the name of Rabbi Johanan that skin disease results from seven sins: slander, the shedding of blood, vain oath, incest, arrogance, robbery, and envy. The Gemara cited Scriptural bases for each of the associations: For slander, Psalm 101:5; for bloodshed, 2 Samuel 3:29; for a vain oath, 2 Kings 5:23–27; for incest, Genesis 12:17; for arrogance, 2 Chronicles 26:16–19; for robbery, Leviticus 14:36 (as a Tanna taught that those who collect money that does not belong to them will see a priest come and scatter their money around the street); and for envy, Leviticus 14:35.[48]

Similarly, a Midrash taught that skin disease resulted from 10 sins: (1) idol-worship, (2) unchastity, (3) bloodshed, (4) the profanation of the Divine Name, (5) blasphemy of the Divine Name, (6) robbing the public, (7) usurping a dignity to which one has no right, (8) overweening pride, (9) evil speech, and (10) an evil eye. The Midrash cited as proofs: (1) for idol-worship, the experience of the Israelites who said of the Golden Calf, "This is your god, O Israel", in Exodus 32:4 and then were smitten with leprosy, as reported in Exodus 32:25, where "Moses saw that the people had broken out (parua, פָרֻעַ)", indicating that leprosy had "broken out" (parah) among them; (2) for unchastity, from the experience of the daughters of Zion of whom Isaiah 3:16 says, "the daughters of Zion are haughty, and walk with stretched-forth necks and ogling eyes", and then Isaiah 3:17 says, "Therefore will the Lord smite with a scab the crown of the head of the daughters of Zion"; (3) for bloodshed, from the experience of Joab, of whom 2 Samuel 3:29 says, "Let it fall upon the head of Joab, and upon all his father's house; and let there not fail from the house of Joab one that hath an issue, or that is a leper," (4) for the profanation of the Divine Name, from the experience of Gehazi, of whom 2 Kings 5:20 says, "But Gehazi, the servant of Elisha the man of God, said: ‘Behold, my master has spared this Naaman the Aramean, in not receiving at his hands that which he brought; as the Lord lives, I will surely run after him, and take of him somewhat (me'umah, מְאוּמָה)," and "somewhat" (me'umah, מְאוּמָה) means "of the blemish" (mum, מוּם) that Naaman had, and thus Gehazi was smitten with leprosy, as 2 Kings 5:20 reports Elisha said to Gehazi, "The leprosy therefore of Naaman shall cleave to you"; (5) for blaspheming the Divine Name, from the experience of Goliath, of whom 1 Samuel 17:43 says, "And the Philistine cursed David by his God", and the 1 Samuel 17:46 says, "This day will the Lord deliver (sagar, סַגֶּרְ) you", and the term "deliver" (sagar, סַגֶּרְ) is used here in the same sense as Leviticus 13:5 uses it with regard to leprosy, when it is says, "And the priest shall shut him up (sagar)"; (6) for robbing the public, from the experience of Shebna, who derived illicit personal benefit from property of the Sanctuary, and of whom Isaiah 22:17 says, "the Lord . . . will wrap you round and round", and "wrap" must refer to a leper, of whom Leviticus 13:45 says, "And he shall wrap himself over the upper lip"; (7) for usurping a dignity to which one has no right, from the experience of Uzziah, of whom 2 Chronicles 26:21 says, "And Uzziah the king was a leper to the day of his death"; (8) for overweening pride, from the same example of Uzziah, of whom 2 Chronicles 26:16 says, "But when he became strong, his heart was lifted up, so that he did corruptly and he trespassed against the Lord his God"; (9) for evil speech, from the experience of Miriam, of whom Numbers 12:1 says, "And Miriam . . . spoke against Moses", and then Numbers 12:10 says, "when the cloud was removed from over the Tent, behold Miriam was leprous"; and (10) for an evil eye, from the person described in Leviticus 14:35, which can be read, "And he that keeps his house to himself shall come to the priest, saying: There seems to me to be a plague in the house," and Leviticus 14:35 thus describes one who is not willing to permit any other to have any benefit from the house.[49]

Similarly, Rabbi Judah the Levite, son of Rabbi Shalom, inferred that skin disease comes because of eleven sins: (1) for cursing the Divine Name, (2) for immorality, (3) for bloodshed, (4) for ascribing to another a fault that is not in him, (5) for haughtiness, (6) for encroaching upon other people's domains, (7) for a lying tongue, (8) for theft, (9) for swearing falsely, (10) for profanation of the name of Heaven, and (11) for idolatry. Rabbi Isaac added: for ill-will. And our Rabbis said: for despising the words of the Torah.[50]

Reading Leviticus 18:4, "My ordinances (מִשְׁפָּטַי, mishpatai) shall you do, and My statutes (חֻקֹּתַי, chukotai) shall you keep", the Sifra distinguished "ordinances" (מִשְׁפָּטִים, mishpatim) from "statutes" (חֻקִּים, chukim). The term "ordinances" (מִשְׁפָּטִים, mishpatim), taught the Sifra, refers to rules that even had they not been written in the Torah, it would have been entirely logical to write them, like laws pertaining to theft, sexual immorality, idolatry, blasphemy and murder. The term "statutes" (חֻקִּים, chukim), taught the Sifra, refers to those rules that the impulse to do evil (יצר הרע, yetzer hara) and the nations of the world try to undermine, like eating pork (prohibited by Leviticus 11:7 and Deuteronomy 14:7–8), wearing wool-linen mixtures (שַׁעַטְנֵז, shatnez, prohibited by Leviticus 19:19 and Deuteronomy 22:11), release from levirate marriage (חליצה, chalitzah, mandated by Deuteronomy 25:5–10), purification of a person affected by skin disease (מְּצֹרָע, metzora, regulated in Leviticus 13–14), and the goat sent off into the wilderness (the "scapegoat," regulated in Leviticus 16). In regard to these, taught the Sifra, the Torah says simply that God legislated them and we have no right to raise doubts about them.[51]

It was taught in a Baraita that four types of people are accounted as though they were dead: a poor person, a person affected by skin disease (מְּצֹרָע, metzora), a blind person, and one who is childless. A poor person is accounted as dead, for Exodus 4:19 says, "for all the men are dead who sought your life" (and the Gemara interpreted this to mean that they had been stricken with poverty). A person affected by skin disease (מְּצֹרָע, metzora) is accounted as dead, for Numbers 12:10–12 says, "And Aaron looked upon Miriam, and behold, she was leprous (מְצֹרָעַת, metzora'at). And Aaron said to Moses . . . let her not be as one dead." The blind are accounted as dead, for Lamentations 3:6 says, "He has set me in dark places, as they that be dead of old". And one who is childless is accounted as dead, for in Genesis 30:1, Rachel said, "Give me children, or else I am dead".[52]

In the priest's examination of skin disease mandated by Leviticus 13:2, 9, and 14:2, the Mishnah taught that a priest could examine anyone else's symptoms, but not his own. And Rabbi Meir taught that the priest could not examine his relatives.[53] The Mishnah taught that anyone could inspect skin disease, but only a priest could declare it unclean or clean.[54] The Mishnah taught that the priests delayed examining a bridegroom — as well as his house and his garment — until after his seven days of rejoicing, and delayed examining anyone until after a holy day.[55]

The Gemara taught that the early scholars were called soferim (related to the original sense of its root safar, "to count") because they used to count all the letters of the Torah (to ensure the correctness of the text). They used to say the vav (ו) in gachon, גָּחוֹן ("belly"), in Leviticus 11:42 marks the half-way point of the letters in the Torah. They used to say the words darosh darash, דָּרֹשׁ דָּרַשׁ ("diligently inquired"), in Leviticus 10:16 mark the half-way point of the words in the Torah. And they used to say Leviticus 13:33 marks the half-way point of the verses in the Torah. Rav Joseph asked whether the vav (ו) in gachon, גָּחוֹן ("belly"), in Leviticus 11:42 belonged to the first half or the second half of the Torah. (Rav Joseph presumed that the Torah contains an even number of letters.) The scholars replied that they could bring a Torah Scroll and count, for Rabbah bar bar Hanah said on a similar occasion that they did not stir from where they were until a Torah Scroll was brought and they counted. Rav Joseph replied that they (in Rabbah bar bar Hanah's time) were thoroughly versed in the proper defective and full spellings of words (that could be spelled in variant ways), but they (in Rav Joseph's time) were not. Similarly, Rav Joseph asked whether Leviticus 13:33 belongs to the first half or the second half of verses. Abaye replied that for verses, at least, we can bring a Scroll and count them. But Rav Joseph replied that even with verses, they could no longer be certain. For when Rav Aha bar Adda came (from the Land of Israel to Babylon), he said that in the West (in the Land of Israel), they divided Exodus 19:9 into three verses. Nonetheless, the Rabbis taught in a Baraita that there are 5,888 verses in the Torah.[56] (Note that others say the middle letter in our current Torah text is the aleph (א) in hu, הוּא ("he"), in Leviticus 8:28; the middle two words are el yesod, אֶל-יְסוֹד ("at the base of"), in Leviticus 8:15; the half-way point of the verses in the Torah is Leviticus 8:7; and there are 5,846 verses in the Torah text we have today.)[57]

Rava recounted a Baraita that taught that the rule of Leviticus 13:45 regarding one with skin disease, "the hair of his head shall be loose", also applied to a High Priest. The status of a High Priest throughout the year corresponded with that of any other person on a festival (with regard to mourning). For the Mishnah said[58] that the High Priest could bring sacrifices on the altar even before he had buried his dead, but he could not eat sacrificial meat. From this restriction of a High Priest, the Gemara inferred that the High Priest would deport himself as a person with skin disease during a festival. And the Gemara continued to teach that a mourner is forbidden to cut his hair, because since Leviticus 10:6 ordained for the sons of Aaron: "Let not the hair of your heads go loose" (after the death of their brothers Nadab and Abihu), we infer that cutting hair is forbidden for everybody else (during mourning), as well.[59]

Rabbi Abbahu, as well as Rabbi Uzziel the grandson of Rabbi Uzziel the Great, taught that Leviticus 13:46 requires that the person afflicted with skin disease "cry, ‘Unclean! Unclean!'" to warn passers-by to keep away. But the Gemara cited a Baraita that taught that Leviticus 13:46 requires that the person "cry, ‘Unclean! Unclean!'" so that the person's distress would become known to many people, so that many could pray for mercy on the afflicted person's behalf. And the Gemara concluded that Leviticus 13:46 reads "Unclean" twice to teach that Leviticus 13:46 is intended to further both purposes, to keep passers-by away and to invite their prayers for mercy.[60]

A Midrash taught that Divine Justice first attacks a person's substance and then the person's body. So when leprous plagues come upon a person, first they come upon the fabric of the person's house. If the person repents, then Leviticus 14:40 requires that only the affected stones need to be pulled out; if the person does not repent, then Leviticus 14:45 requires pulling down the house. Then the plagues come upon the person's clothes. If the person repents, then the clothes require washing; if not, they require burning. Then the plagues come upon the person's body. If the person repents, Leviticus 14:1–32 provides for purification; if not, then Leviticus 13:46 ordains that the person "shall dwell alone".[61]

Similarly, the Tosefta reported that when a person would come to the priest, the priest would tell the person to engage in self-examination and turn from evil ways. The priest would continue that plagues come only from gossip, and skin disease from arrogance. But God would judge in mercy. The plague would come to the house, and if the homeowner repented, the house required only dismantling, but if the homeowner did not repent, the house required demolition. They would appear on clothing, and if the owner repented, the clothing required only tearing, but if the owner did not repent, the clothing required burning. They would appear on the person's body, and if the person repented, well and good, but if the person did not repent, Leviticus 13:46 required that the person "shall dwell alone".[62]

Rabbi Samuel bar Elnadab asked Rabbi Haninah (or others say Rabbi Samuel bar Nadab the son-in-law of Rabbi Haninah asked Rabbi Haninah, or still others say, asked Rabbi Joshua ben Levi) what distinguished the person afflicted with skin disease that Leviticus 13:46 ordains that the person "shall dwell alone". The answer was that through gossip, the person afflicted with skin disease separated husband from wife, one neighbor from another, and therefore the Torah punished the person afflicted with skin disease measure for measure, ordaining that the person "shall dwell alone".[63]

In a Baraita, Rabbi Jose related that a certain Elder from Jerusalem told him that 24 types of patients are afflicted with boils. The Gemara then related that Rabbi Joḥanan warned to be careful of the flies found on those afflicted with the disease ra’atan, as flies carried the disease. Rabbi Zeira would not sit in a spot where the wind blew from the direction of someone afflicted with ra’atan. Rabbi Elazar would not enter the tent of one afflicted with ra’atan, and Rabbi Ami and Rabbi Asi would not eat eggs from an alley in which someone afflicted with ra’atan lived. Rabbi Joshua ben Levi, however, would attach himself to those afflicted with ra’atan and study Torah, saying this was justified by Proverbs 5:19, “The Torah is a loving hind and a graceful doe.” Rabbi Joshua reasoned that if Torah bestows grace on those who learn it, it could protect them from illness. When Rabbi Joshua ben Levi was on the verge of dying, the Gemara told, the Angel of Death was instructed to perform Rabbi Joshua’s bidding, as he was a righteous man and deserves to die in the manner he saw fit. Rabbi Joshua ben Levi asked the Angel of Death to show him his place in paradise, and the Angel agreed. Rabbi Joshua ben Levi asked the Angel to give him the knife that the Angel used to kill people, lest the Angel frighten him on the way, and the Angel gave it to him. When they arrived in paradise, the Angel lifted Rabbi Joshua so that he could see his place in paradise, and Rabbi Joshua jumped to the other side, escaping into paradise. Elijah the Prophet then told those in paradise to make way for Rabbi Joshua.[64]

The Gemara told that Rabbi Joshua ben Levi asked Elijah when the Messiah would come, and Elijah told Rabbi Joshua ben Levi that he could find the Messiah sitting at the entrance of the city of Rome among the poor who suffer from illnesses.[65]

In medieval Jewish interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these medieval Jewish sources:[66]

Leviticus chapter 12

Maimonides taught that the laws of impurity serve many uses: (1) They keep Jews at a distance from dirty and filthy objects. (2) They guard the Sanctuary. (3) They pay regard to an established custom. (4) They lightened the burden. For these laws do not impede people affected with impurity in their ordinary occupations. For the distinction between pure and impure applies only with reference to the Sanctuary and the holy objects connected with it; it does not apply to other cases. Citing Leviticus 12:4, "She shall touch no hallowed thing, nor come into the Sanctuary," Maimonides noted that people who do not intend to enter the Sanctuary or touch any holy thing are not guilty of any sin if they remain unclean as long as they like, and eat, according to their pleasure, ordinary food that has been in contact with unclean things.[67]

In modern interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these modern sources:

Leviticus chapter 12

Dr. Elaine Goodfriend of California State University, Northridge, observed that Leviticus 12 and its focus on menstruating women had an enormous effect on Jewish women's lives. Goodfriend reported that "the view that women — via their normal, recurring bodily functions — generate a pollution antagonistic to holiness served as a justification for women's distance from the sacred throughout Jewish history." Goodfriend speculated the priesthood excluded women because of "fear that the sudden onset of menstruation would result in the clash of impurity and holiness, with presumed dire consequences." Goodfriend noted that these laws and associated customs affected both women's public religious life and private family life, as they and their husbands were prohibited from sex for extensive periods of time, affecting their fertility and married life in general.[68]

Professor Shaye Cohen of Harvard University noted that the only element in common between the “ritual” or physical impurities of Leviticus 11–15 and the “dangerous” or sinful impurities of Leviticus 18 is intercourse with a menstruant.[69]

Leviticus chapter 13

Professor Ephraim Speiser of the University of Pennsylvania in the mid 20th century wrote that the word “Torah” (תּוֹרָה) is based on a verbal stem signifying “to teach, guide,” and the like, and the derived noun can carry a variety of meanings, including in Leviticus 13:59, 14:2, 54, and 57, specific rituals for what is sometimes called leprosy. Speiser argued that in context, the word cannot be mistaken for the title of the Pentateuch as a whole.[70]

Commandments

According to Maimonides

Maimonides cited verses in this parashah for 3 positive and 1 negative commandments:[71]

- To circumcise the son, as it is written "and on the eighth day the flesh of his foreskin shall be circumcised"[72]

- For a woman after childbirth to bring a sacrifice after she becomes clean, as it is written "and when the days of her purification are fulfilled"[73]

- Not to shave off the hair of the scall, as it is written "but the scall shall he not shave"[74]

- For the person with skin disease to be known to all by the things written about the person, "his clothes shall be rent, and the hair of his head shall go loose, and he shall cover his upper lip, and shall cry: 'unclean, unclean.'"[75] So too, all other unclean persons must declare themselves.

According to Sefer ha-Chinuch

According to Sefer ha-Chinuch, there are 5 positive and 2 negative commandments in the parashah:[76]

- The precept about the ritual uncleanness of a woman after childbirth[77]

- A ritually unclean person is not to eat meat of holy sacrifices.[78]

- The precept of a woman's offering after giving birth[73]

- The precept regarding the ritual uncleanness of a m'tzora (person with skin disease (צָּרַעַת, tzara'at)[79]

- The prohibition against shaving the area of a nethek (an impurity in hair)[74]

- That one with skin disease (צָּרַעַת, tzara'at), among others, should rend clothes.[75]

- The precept of צָּרַעַת, tzara'at in cloth[80]

In the liturgy

Some Jews refer to the laws of bird offerings in Leviticus 12:8 and the laws of the menstrual cycle as they study the end of chapter 3 of Pirkei Avot on a Sabbath between Passover and Rosh Hashanah.[81]

Some Jews refer to the guilt offerings for skin disease in Leviticus 13 as part of readings on the offerings after the Sabbath morning blessings.[82]

Following the Shacharit morning prayer service, some Jews recite the Six Remembrances, among which is Deuteronomy 24:9, "Remember what the Lord your God did to Miriam by the way as you came forth out of Egypt," recalling that God punished Miriam with צָּרַעַת, tzara'at.[83]

The Weekly Maqam

In the Weekly Maqam, Sephardi Jews each week base the songs of the services on the content of that week's parashah. For parashah Tazria, Sephardi Jews apply Maqam Saba, the maqam that symbolizes a covenant (brit). This is appropriate, because this parashah commences with the discussion of what to do when a baby boy is born. It also mentions the brit milah, a ritual that shows a covenant between man and God.

Haftarah

The haftarah for the parashah (when read individually on a Sabbath that is not a special Sabbath) is 2 Kings 4:42–5:19.

Summary

A man from Baal-shalishah brought the prophet Elisha bread of the First Fruits — 20 loaves of barley — and fresh grain in his sack to give to the people to eat.[84] Elisha's servant asked Elisha how he could feed a hundred men with these rations, but Elisha told his servant to give the food to the people, for God said that they would eat and have food left over.[85] So the servant set the food before the men, they ate, and they had food left over, just as God had said.[86]

Naaman, the commander of the army of the king of Aram, was a great warrior, but he was a leper.[87] The girl who waited on Naaman's wife was an Israelite whom the Arameans had taken captive, and she told Naaman's wife that if Naaman went to Elisha in Samaria, then Elisha would cure Naaman of his leprosy.[88] Naaman told his lord the king of Aram what the girl said, and the king of Aram sent Naaman on his way with a letter to the king of Israel.[89] Naaman departed, taking with him ten talents of silver, 6,000 pieces of gold, and ten changes of clothes.[90] Naaman brought the king of Israel the letter, which asked the king of Israel to cure Naaman of his leprosy.[91] When the king of Israel read the letter, he rent his clothes and complained that he was not God with power over life and death, but the king of Aram must have been seeking some pretext to attack Israel.[92]

When Elisha heard, he invited the king to send Naaman to him, and so Naaman came to Elisha's house with his horses and his chariots.[93] Elisha sent a messenger to Naaman to tell him to wash seven times in the Jordan River and be healed, but that angered Naaman, who expected Elisha to come out, call on the name of God, and wave his hands over Naaman.[94] Naaman asked whether the Amanah and Pharpar rivers of Damascus were not better than any river in Israel, so that he might wash in them and be clean.[95]

But Naaman's servants advised him that if Elisha had directed him to do some difficult thing he would have done it, so how much more should he do what Elisha directed when he said merely to wash and be clean.[96] So Naaman dipped himself seven times in the Jordan, and his flesh came back like the flesh of a little child.[97]

Naaman returned to Elisha, avowed that there is no God except in Israel, and asked Elisha to take a present, but Elisha declined.[98] Naaman asked if he might take two mule loads of Israel's earth so that Naaman might make offerings to God, and he asked that God might pardon Naaman when had had to bow before the Aramean idol Rimmon when the king of Aram leaned on Naaman to bow before Rimmon.[99] And Elisha told Naaman to go in peace.[100]

Connection to the parashah

Both the parashah and the haftarah report the treatment of skin disease, the parashah by the priests,[101] and the haftarah by the prophet Elisha.[102] Both the parashah and the haftarah frequently employ the term for skin disease (צָּרַעַת, tzara'at).[103]

A Midrash deduced from the characterization of Naaman as a "great man" in 2 Kings 5:1 that Naaman was haughty on account of his being a great warrior, and as a result was smitten with leprosy.[50]

And fundamentally, both the parashah and the haftarah view skin disease as related to the Divine sphere and an occasion for interaction with God.

The haftarah in classical rabbinic interpretation

The Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael considered Naaman a more righteous convert than Jethro. Reading Jethro’s words in Exodus 18:11, "Now I know that the Lord is greater than all gods," the Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael reported that they said that there was not an idol in the world that Jethro failed to seek out and worship, for Jethro said "than all gods." The Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael taught that Naaman, however, knew better than Jethro that there was no other god, for Naaman said in 2 Kings 5:15, "Behold now, I know that there is no God in all the earth, but in Israel."[104] The Babylonian Talmud, however, taught that Naaman was merely a resident alien who observed the seven Noahide commandments (including the prohibition on idolatry).[105]

On Shabbat HaChodesh

When the parashah coincides with Shabbat HaChodesh ("Sabbath [of] the month," the special Sabbath preceding the Hebrew month of Nissan — as it does in 2019 and 2022), the haftarah is:[2]

Connection to the Special Sabbath

On Shabbat HaChodesh, Jews read Exodus 12:1–20, in which God commands that "This month [Nissan] shall be the beginning of months; it shall be the first month of the year,"[106] and in which God issued the commandments of Passover.[107] Similarly, the haftarah in Ezekiel 45:21–25 discusses Passover. In both the special reading and the haftarah, God instructs the Israelites to apply blood to doorposts.[108]

Parashah Tazria-Metzora

When parashah Tazria is combined with parashah Metzora (as it is in 2018, 2020, 2021, 2025, and 2028) and it is not a special Sabbath, the haftarah is the haftarah for parashah Metzora, 2 Kings 7:3–20.[109]

Summary

During the Arameans' siege of Samaria, four leprous men at the gate asked each other why they should die there of starvation, when they might go to the Arameans, who would either save them or leave them no worse than they were.[110] When at twilight, they went to the Arameans' camp, there was no one there, for God had made the Arameans hear chariots, horses, and a great army, and fearing the Hittites and the Egyptians, they fled, leaving their tents, their horses, their donkeys, and their camp.[111] The lepers went into a tent, ate and drank, and carried away silver, gold, and clothing from the tents and hid it.[112]

Feeling qualms of guilt, they went to go tell the king of Samaria, and called to the porters of the city telling them what they had seen, and the porters told the king's household within.[113] The king arose in the night, and told his servants that he suspected that the Arameans had hidden in the field, thinking that when the Samaritans came out, they would be able to get into the city.[114] One of his servants suggested that some men take five of the horses that remained and go see, and they took two chariots with horses to go and see.[115] They went after the Arameans as far as the Jordan River, and all the way was littered with garments and vessels that the Arameans had cast away in their haste, and the messengers returned and told the king.[116] So the people went out and looted the Arameans' camp, so that the price of fine flour and two measures of barley each dropped to a shekel, as God had said it would.[117] And the king appointed the captain on whom he leaned to take charge of the gate, and the people trampled him and killed him before he could taste of the flour, just as the man of God Elisha had said.[118]

Connection to the double parashah

Both the double parashah and the haftarah deal with people stricken with skin disease. Both the parashah and the haftarah employ the term for the person affected by skin disease (metzora, מְּצֹרָע).[119] In parashah Tazria, Leviticus 13:46 provides that the person with skin disease "shall dwell alone; without the camp shall his dwelling be," thus explaining why the four leprous men in the haftarah lived outside the gate.[120]

Rabbi Johanan taught that the four leprous men at the gate in 2 Kings 7:3 were none other than Elisha's former servant Gehazi (whom the Midrash, above, cited as having been stricken with leprosy for profanation of the Divine Name) and his three sons.[121]

In parashah Metzora, when there "seems" to be a plague in the house,[122] the priest must not jump to conclusions, but must examine the facts.[123] Just before the opening of the haftarah, in 2 Kings 7:2, the captain on whom the king leaned jumps to the conclusion that Elisha's prophecy could not come true, and the captain meets his punishment in 2 Kings 7:17 and 19.[124]

On Shabbat Rosh Chodesh

When the combined parashah coincides with Shabbat Rosh Chodesh (as it does in 2020, 2023, and 2026), the haftarah is Isaiah 66:1–24.[109]

Notes

- "Torah Stats — VaYikra". Akhlah Inc. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- "Parashat Tazria". Hebcal. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- See, e.g., The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Vayikra/Leviticus. Edited by Menachem Davis, pages 74–88. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2008. ISBN 1-4226-0206-0.

- Leviticus 12:1–5.

- Leviticus 12:6–7.

- Leviticus 12:8.

- Leviticus 13:1–5.

- Leviticus 13:6–8.

- Leviticus 13:9–17.

- Leviticus 13:18–23.

- Leviticus 13:24–28.

- Leviticus 13:29–39.

- Leviticus 13:40–44.

- Leviticus 13:45–46.

- Leviticus 13:47–51.

- Leviticus 13:52–54.

- Leviticus 13:55–59.

- For more on inner-Biblical interpretation, see, e.g., Benjamin D. Sommer. "Inner-biblical Interpretation." In The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, pages 1835–41. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014. ISBN 978-0-19-997846-5.

- For more on early nonrabbinic interpretation, see, e.g., Esther Eshel. "Early Nonrabbinic Interpretation." In The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, pages 1841–59.

- Philo, On the Unchangableness of God 27:129 (Alexandria, Egypt, early 1st century CE), in, e.g., The Works of Philo: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition, translated by Charles Duke Yonge (Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 1993), page 169.

- For more on classical rabbinic interpretation, see, e.g., Yaakov Elman. "Classical Rabbinic Interpretation." In The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, pages 1859–78.

- Leviticus Rabbah 14:1 (Land of Israel, 5th century) in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Leviticus, translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon (London: Soncino Press, 1939), volume 4, pages 178–79.

- Leviticus Rabbah 14:2. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Leviticus. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 4, page 180.

- Babylonian Talmud Nidah 27b. Babylonia, 6th century.

- Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 132a.

- Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 132b.

- Mishnah Megillah 2:4 (Land of Israel, circa 200 CE), in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation, translated by Jacob Neusner (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988), page 319; Babylonian Talmud Megillah 20a, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli, elucidated by Gedaliah Zlotowitz and Hersh Goldwurm, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1991), volume 20, page 20a.

- Babylonian Talmud Megillah 20a, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli, elucidated by Gedaliah Zlotowitz and Hersh Goldwurm, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr, volume 20, page 20a.

- Babylonian Talmud Pesachim 4a, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli, elucidated by Abba Zvi Naiman, Eliezer Herzka, and Moshe Zev Einhorn, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz, (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1997), volume 9, page 4a; Babylonian Talmud Yoma 28b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli, elucidated by Abba Zvi Naiman, Michoel Weiner, Yosef Widroff, Moshe Zev Einhorn, Israel Schneider, and Zev Meisels, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1998), volume 13, pages 28b.

- Babylonian Talmud Niddah 31b.

- Genesis Rabbah 20:7. Land of Israel, 5th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Genesis. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 1, pages 165–66. London: Soncino Press, 1939. ISBN 0-900689-38-2.

- Mishnah Menachot 13:11, in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, page 765; Babylonian Talmud Menachot 110a, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli, elucidated by Yosef Davis, Eliezer Herzka, Abba Zvi Naiman, Zev Meisels, Noson Boruch Herzka, and Avrohom Neuberger, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2003), volume 60, page 110a3; see also Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 5b, in, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Berakhot. Commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz) (Jerusalem: Koren Publishers, 2012), volume 1, page 29.

- Babylonian Talmud Menachot 110a, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli, elucidated by Yosef Davis, Eliezer Herzka, Abba Zvi Naiman, Zev Meisels, Noson Boruch Herzka, and Avrohom Neuberger, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz, volume 60, page 110a3–4.

- Babylonian Talmud Menachot 104b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli, elucidated by Yosef Davis, Eliezer Herzka, Abba Zvi Naiman, Zev Meisels, Noson Boruch Herzka, and Avrohom Neuberger, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz, volume 60, page 104b2.

- Mishnah Keritot 6:9, in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation, translated by Jacob Neusner, pages 850–51; Babylonian Talmud Keritot 28a, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli, elucidated by Eliahu Shulman, Dovid Arye Kaufman, Dovid Nachfolger, Menachem Goldberger, Michoel Weiner, Mendy Wachsman, Abba Zvi Naiman, and Zev Meisels, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2004), volume 69, page 28a.

- Mishnah Avot 3:18, in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation, translated by Jacob Neusner, page 681.

- Mishnah Kinnim 1:1–3:6. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, pages 883–89.

- Mishnah Arakhin 2:1, in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation, translated by Jacob Neusner, page 811; Babylonian Talmud Arakhin 8a, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli, elucidated by Mendy Wachsman, Feivel Wahl, Yosef Davis, Henoch Moshe Levin, Israel Schneider, Yeshayahu Levy, Eliezer Herzka, Dovid Nachfolger, Eliezer Lachman, and Zev Meisels, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2004), volume 67, page 8a.

- Mishnah Zevachim 10:4, in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation, translated by Jacob Neusner, page 722; Babylonian Talmud Zevachim 89a, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli, elucidated by Israel Schneider, Yosef Widroff, Mendy Wachsman, Dovid Katz, Zev Meisels, and Feivel Wahl, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1996), volume 57, page 89a.

- Babylonian Talmud Zevachim 90a, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli, elucidated by Israel Schneider et al., volume 57, page 90a.

- Babylonian Talmud Yoma 41a, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli, elucidated by Abba Zvi Naiman et al., volume 13, page 41a.

- See Exodus 6:13, 7:8, 9:8, 12:1, 12:43, 12:50; Leviticus 11:1, 13:1, 14:33, 15:1; Numbers 2:1, 4:1, 4:17 14:26, 16:20, 19:1, 20:12, 20:23.

- Numbers Rabbah 2:1. 12th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Numbers. Translated by Judah J. Slotki, volume 5, page 22. London: Soncino Press, 1939. ISBN 0-900689-38-2.

- Mishnah Negaim 1:1–14:13, in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation, translated by Jacob Neusner, pages 981–1012; Tosefta Negaim 1:1–9:9 (Land of Israel, circa 300 CE), in, e.g., The Tosefta: Translated from the Hebrew, with a New Introduction, translated by Jacob Neusner (Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 2002), volume 2, pages 1709–44.

- Leviticus Rabbah 15:4.

- Babylonian Talmud Arakhin 15b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli, elucidated by Mendy Wachsman et al., volume 67, pages 15b2–5.

- Deuteronomy Rabbah 6:8 (Land of Israel, circa 775–900 CE), in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Deuteronomy, translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon (London: Soncino Press, 1939), volume 7, pages 125–26.

- Babylonian Talmud Arakhin 16a, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli, elucidated by Mendy Wachsman et al., volume 67, page 16a.

- Leviticus Rabbah 17:3.

- Numbers Rabbah 7:5.

- Sifra Aharei Mot pereq 13, 194:2:11. Reprinted in, e.g., Sifra: An Analytical Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, volume 3, page 79. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1988. ISBN 1-55540-207-0.

- Babylonian Talmud Nedarim 64b. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Elucidated by Eliezer Herzka, Asher Dicker, Nasanel Kasnett, Noson Boruch Herzka, Reuvein Dowek, Michoel Weiner, Mendy Wachsman, and Feivel Wahl; edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz, volume 30, page 64b3. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2000. ISBN 1-57819-648-5.

- Mishnah Negaim 2:5, in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation, translated by Jacob Neusner, page 984; Deuteronomy Rabbah 6:8, in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Deuteronomy, translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 7, pages 125–26.

- Mishnah Negaim 3:1, in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation, translated by Jacob Neusner, page 984.

- Mishnah Negaim 3:2, in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation, translated by Jacob Neusner, pages 984–85.

- Babylonian Talmud Kiddushin 30a.

- E.g., Michael Pitkowsky, "The Middle Verse of the Torah" and the response of Reuven Wolfeld there.

- See Mishnah Horayot 3:5. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, page 695. Babylonian Talmud Horayot 12b.

- Babylonian Talmud Moed Katan 14b.

- Babylonian Talmud Moed Katan 5a.

- Leviticus Rabbah 17:4. Ruth Rabbah 2:10.

- Tosefta Negaim 6:7, in, e.g., The Tosefta: Translated from the Hebrew, with a New Introduction, translated by Jacob Neusner, volume 2, pages 1731–32.

- Babylonian Talmud Arakhin 16b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli, elucidated by Mendy Wachsman et al., volume 67, page 16b.

- Babylonian Talmud Ketubot 77b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli, elucidated by Mendy Wachsman, Abba Zvi Naiman, and Eliahu Shulman, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz, and Mordechai Marcus Hersh Goldwurm (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2000), volume 27, pages 77b1–3.

- Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 98a, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli, elucidated by Asher Dicker, Joseph Elias, and Dovid Katz, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1995), volume 49, page 98a5.

- For more on medieval Jewish interpretation, see, e.g., Barry D. Walfish. "Medieval Jewish Interpretation." In The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, pages 1891–1915.

- Maimonides. The Guide for the Perplexed, part 3, chapter 47. Cairo, Egypt, 1190. Reprinted in, e.g., Moses Maimonides. The Guide for the Perplexed. Translated by Michael Friedländer, page 368. New York: Dover Publications, 1956. ISBN 0-486-20351-4.

- Elaine Goodfriend, "Tazria: Leviticus 12:1–13:59: Purity, Birth, and Illness," in Tamara Cohn Eskenazi and Andrea L. Weiss, editors, The Torah: A Women's Commentary (New York: URJ Press, 2008), pages 637–38.

- Shaye J.D. Cohen, "Menstruants and the Sacred in Judaism and Christianity," in Women’s History and Ancient History, edited by Sarah B. Pomeroy (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), page 275.

- Ephraim A. Speiser. Genesis: Introduction, Translation, and Notes, volume 1, page xviii. New York: Anchor Bible, 1964.

- Maimonides. Mishneh Torah, Positive Commandments 76, 112, 215; Negative Commandment 307. Cairo, Egypt, 1170–1180. Reprinted in Maimonides. The Commandments: Sefer Ha-Mitzvoth of Maimonides. Translated by Charles B. Chavel, volume 1, pages 88, 123–24, 230–31; volume 2, pages 283–84. London: Soncino Press, 1967. ISBN 0-900689-71-4.

- Leviticus 12:3.

- Leviticus 12:6.

- Leviticus 13:33.

- Leviticus 13:45.

- Sefer HaHinnuch: The Book of [Mitzvah] Education. Translated by Charles Wengrov, volume 2, pages 201–33. Jerusalem: Feldheim Publishers, 1984. ISBN 0-87306-296-5.

- Leviticus 12:2.

- Leviticus 12:4.

- Leviticus 13:12.

- Leviticus 13:47.

- Menachem Davis. The Schottenstein Edition Siddur for the Sabbath and Festivals with an Interlinear Translation, page 556. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2002. ISBN 1-57819-697-3.

- Davis, Siddur for the Sabbath and Festivals, page 239.

- Menachem Davis. The Schottenstein Edition Siddur for Weekdays with an Interlinear Translation, page 241. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2002. ISBN 1-57819-686-8. Yosaif Asher Weiss. A Daily Dose of Torah, volume 7, pages 139–40. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2007. ISBN 1-4226-0145-5.

- 2 Kings 4:42.

- 2 Kings 4:43.

- 2 Kings 4:44.

- 2 Kings 5:1.

- 2 Kings 5:2–3.

- 2 Kings 5:4–5.

- 2 Kings 5:5.

- 2 Kings 5:6.

- 2 Kings 5:7.

- 2 Kings 5:8–9.

- 2 Kings 5:10–11.

- 2 Kings 5:12.

- 2 Kings 5:13.

- 2 Kings 5:14.

- 2 Kings 5:15–16.

- 2 Kings 5:17–18.

- 2 Kings 5:19.

- See Leviticus 13.

- See 2 Kings 5.

- Leviticus 13:3, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 15, 20, 25, 27, 30, 42, 43, 49, 51, 52, 59; 2 Kings 5:3, 6, 7.

- Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael, tractate Amalek, chapter 3. Land of Israel, late 4th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Mekhilta de-Rabbi Ishmael. Translated by Jacob Z. Lauterbach, volume 2, page 280. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1933, reissued 2004. ISBN 0-8276-0678-8.

- Babylonian Talmud Gittin 57b. Reprinted in, e.g., Koren Talmud Bavli: Gittin. Commentary by Adin Even-Israel (Steinsaltz), volume 21, pages 324. Jerusalem: Koren Publishers, 2015. ISBN 978-965-301-582-1. Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 96b, in, e.g., The Talmud: The Steinsaltz Edition. Commentary by Adin Steinsaltz (Even Yisrael), volume 20, page 164. New York: Random House, 1999.

- Exodus 12:2.

- Exodus 12:3–20.

- Exodus 12:7; Ezekiel 45:19.

- "Parashat Tazria-Metzora". Hebcal. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- 2 Kings 7:3–4.

- 2 Kings 7:5–7.

- 2 Kings 7:8.

- 2 Kings 7:9–11.

- 2 Kings 7:12.

- 2 Kings 7:13–14.

- 2 Kings 7:15.

- 2 Kings 7:16.

- 2 Kings 7:17–20.

- Leviticus 14:2; 2 Kings 7:3, 8.

- 2 Kings 7:3.

- Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 107b, in, e.g., Talmud Bavli, elucidated by Asher Dicker, Joseph Elias, and Dovid Katz, edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr and Chaim Malinowitz, volume 49, page 107b.

- Leviticus 14:35.

- Leviticus 14:36–37, 39, 44.

- See Lainie Blum Cogan and Judy Weiss. Teaching Haftarah: Background, Insights, and Strategies, page 203. Denver: A.R.E. Publishing, 2005. ISBN 0-86705-054-3.

Further reading

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these sources:

Biblical

- Genesis 17:12 (circumcision).

- Psalms 72:12 (God's help for the needy who cry out); 147:3 (God's healing).

Early nonrabbinic

- Jubilees 3:8–14 Land of Israel, 2nd century BCE. (days of defilement after childbirth).

- Philo. On the Posterity of Cain and His Exile 13:47; On the Unchangableness of God 25:123–24; 27:127; Concerning Noah's Work as a Planter 26:111; On the Prayers and Curses Uttered by Noah When He Became Sober 10:49. Alexandria, Egypt, early 1st century CE. Reprinted in, e.g., The Works of Philo: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition. Translated by Charles Duke Yonge, pages 136, 168, 200, 231. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 1993. ISBN 0-943575-93-1.

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 3:11:3–5. Circa 93–94. Reprinted in, e.g., The Works of Josephus: Complete and Unabridged, New Updated Edition. Translated by William Whiston, pages 96–97. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 1987. ISBN 0-913573-86-8.

- Luke 2:22 (days of purification after birth).

Classical rabbinic

- Mishnah: Megillah 2:4; Nazir 7:3; Sotah 3:8; Avot 3:18; Horayot 3:5; Zevachim 10:4; Arakhin 2:1, Keritot 6:9; Kinnim 1:1–3:6; Negaim 1:1–14:13. Land of Israel, circa 200 CE. Reprinted in, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, pages 319, 444, 453, 681, 695, 722, 811, 851, 883–89, 981–1012. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-300-05022-4.

- Tosefta: Bikkurim 2:6; Shabbat 8:27; Megillah 2:4; Sotah 6:7; Eduyot 2:4; Negaim 1:1–9:9. Land of Israel, circa 250 CE. Reprinted in, e.g., The Tosefta: Translated from the Hebrew, with a New Introduction. Translated by Jacob Neusner, volume 1, pages 350, 385, 857; volume 2, pages 1253, 1709–44. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 2002. ISBN 1-56563-642-2.

- Sifra 121:1–147:16. Land of Israel, 4th century CE. Reprinted in, e.g., Sifra: An Analytical Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, volume 2, pages 231–323. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1988. ISBN 1-55540-206-2.

- Jerusalem Talmud: Kilayim 76a; Maaser Sheni 46b; Shabbat 10b, 19a, 98a; Pesachim 14b, 45b, 55a, 78a; Rosh Hashanah 5b; Megillah 12a, 25b; Yevamot 44a; Nedarim 12b–13a, 31a; Nazir 20a, 52a; Sotah 19b, 44a; Kiddushin 19b; Niddah 1a–. Tiberias, Land of Israel, circa 400 CE. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Yerushalmi. Edited by Chaim Malinowitz, Yisroel Simcha Schorr, and Mordechai Marcus, volumes 5, 10, 13, 15, 18–19, 24, 26, 30, 33–37, 40. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2008–2017. And reprinted in, e.g., The Jerusalem Talmud: A Translation and Commentary. Edited by Jacob Neusner and translated by Jacob Neusner, Tzvee Zahavy, B. Barry Levy, and Edward Goldman. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 2009. ISBN 978-1-59856-528-7.

- Mekhilta of Rabbi Simeon 10:2. Land of Israel, 5th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Mekhilta de-Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai. Translated by W. David Nelson, page 31. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2006. ISBN 0-8276-0799-7.

- Leviticus Rabbah 2:6; 5:5; 14:1–16:1; 16:3–4, 6; 17:3–4; 18:2, 4–5; 21:2; 27:1, 10; 36:1. Land of Israel, 5th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Leviticus. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 4, pages 24, 70, 177–98, 202, 205–07, 216–17, 219, 229, 232–33, 266, 344, 354, 456. London: Soncino Press, 1939. ISBN 0-900689-38-2.

.jpg)

- Babylonian Talmud: Berakhot 4a, 5b, 25a; Shabbat 2b, 24b, 26b, 28a, 54a, 55b, 67a, 94b, 132a–b, 134b–35a; Eruvin 24a, 32a, 37a; Pesachim 3a, 4a, 9b, 67a–b, 75a, 84a, 90b, 92a, 113b; Yoma 6a, 9b, 28b, 34b, 41a, 42a, 81a; Sukkah 28b; Megillah 8b, 20a, 24b; Moed Katan 5a, 7a–8a, 14b–15a; Chagigah 11a, 18b; Yevamot 4b, 47b, 72b, 74b–75a, 83a, 103b–04a; Ketubot 61b, 75b; Nedarim 4b; Nazir 17b, 26b–27a, 29a, 43a, 54b, 56b, 59b, 64b, 65b; Sotah 5a, 23a, 32b; Kiddushin 13b, 25a, 30a, 35b; Bava Kamma 11a, 80a, 92b; Bava Metzia 86a; Bava Batra 84a, 127a; Sanhedrin 4a, 11a, 26a, 34b, 54b, 59b, 68a, 83b, 87b–88a, 97a, 101a; Makkot 8b, 14b, 20b, 22a; Shevuot 2a, 6a–7a, 8a, 11a, 16a, 17b; Avodah Zarah 23b, 42a; Horayot 10a; Zevachim 19b, 32b, 33b, 38a, 49b, 67b, 76b, 90a, 94a, 102a, 105b, 112b, 117a; Menachot 4b, 6b, 37b, 39b, 91b; Chullin 8a, 24a, 31b, 41b, 51b, 63a, 71a, 77b–78a, 84b–85a, 109b, 134a; Bekhorot 17a, 27b, 34b, 41a, 47b; Arakhin 3a, 8b, 15b–16b, 18b, 21a; Temurah 26b; Keritot 7b–8b, 9b–10b, 22b, 28a; Meilah 19a; Niddah 11a–b, 15b, 19a, 20b–21a, 24b, 27b, 30b–31a, 34a–b, 35b, 36b, 37b, 38b, 40a, 44a, 47b, 50a, 66a, 71b. Babylonia, 6th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr, Chaim Malinowitz, and Mordechai Marcus, 72 volumes. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2006.

- Deuteronomy Rabbah 6:8. Land of Israel, circa 775–900 CE. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Deuteronomy. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 7, pages 125–26. London: Soncino Press, 1939.

Medieval

- Solomon ibn Gabirol. A Crown for the King, 30:369–70. Spain, 11th century. Translated by David R. Slavitt, pages 48–49. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-19-511962-2.

- Maimonides. The Guide for the Perplexed, part 1, chapter 42; part 3, chapters 41, 45, 47, 49. Cairo, Egypt, 1190. Reprinted in, e.g., Moses Maimonides. The Guide for the Perplexed. Translated by Michael Friedländer, pages 56, 346, 357, 368, 379. New York: Dover Publications, 1956. ISBN 0-486-20351-4.

- Rashi. Commentary. Leviticus 12–13. Troyes, France, late 11th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Rashi. The Torah: With Rashi's Commentary Translated, Annotated, and Elucidated. Translated and annotated by Yisrael Isser Zvi Herczeg, volume 3, pages 135–57. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1994. ISBN 0-89906-028-5.

- Rashbam. Commentary on the Torah. Troyes, early 12th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Rashbam's Commentary on Leviticus and Numbers: An Annotated Translation. Edited and translated by Martin I. Lockshin, pages 69–76. Providence: Brown Judaic Studies, 2001. ISBN 1-930675-07-0.

- Abraham ibn Ezra. Commentary on the Torah. Mid-12th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Ibn Ezra's Commentary on the Pentateuch: Leviticus (Va-yikra). Translated and annotated by H. Norman Strickman and Arthur M. Silver, volume 3, pages 85–102. New York: Menorah Publishing Company, 2004. ISBN 0-932232-11-6.

- Hezekiah ben Manoah. Hizkuni. France, circa 1240. Reprinted in, e.g., Chizkiyahu ben Manoach. Chizkuni: Torah Commentary. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 3, pages 713–28. Jerusalem: Ktav Publishers, 2013. ISBN 978-1-60280-261-2.

- Nachmanides. Commentary on the Torah. Jerusalem, circa 1270. Reprinted in, e.g., Ramban (Nachmanides): Commentary on the Torah. Translated by Charles B. Chavel, volume 3, pages 156–85. New York: Shilo Publishing House, 1974. ISBN 0-88328-007-8.

- Zohar 3:42a–52a. Spain, late 13th century. Reprinted in, e.g., The Zohar. Translated by Harry Sperling and Maurice Simon. 5 volumes. London: Soncino Press, 1934.

- Bahya ben Asher. Commentary on the Torah. Spain, early 14th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Midrash Rabbeinu Bachya: Torah Commentary by Rabbi Bachya ben Asher. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 5, pages 1621–52. Jerusalem: Lambda Publishers, 2003. ISBN 965-7108-45-4.

- Jacob ben Asher (Baal Ha-Turim). Commentary on the Torah. Early 14th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Baal Haturim Chumash: Vayikra/Leviticus. Translated by Eliyahu Touger; edited, elucidated, and annotated by Avie Gold, volume 3, pages 1113–37. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2000. ISBN 1-57819-130-0.

- Jacob ben Asher. Perush Al ha-Torah. Early 14th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Yaakov ben Asher. Tur on the Torah. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 3, pages 852–67. Jerusalem: Lambda Publishers, 2005. ISBN 978-9657108765.

- Isaac ben Moses Arama. Akedat Yizhak (The Binding of Isaac). Late 15th century. Reprinted in, e.g., Yitzchak Arama. Akeydat Yitzchak: Commentary of Rabbi Yitzchak Arama on the Torah. Translated and condensed by Eliyahu Munk, volume 2, pages 577–87. New York, Lambda Publishers, 2001. ISBN 965-7108-30-6.

Modern

- Isaac Abravanel. Commentary on the Torah. Italy, between 1492–1509. Reprinted in, e.g., Abarbanel: Selected Commentaries on the Torah: Volume 3: Vayikra/Leviticus. Translated and annotated by Israel Lazar, pages 106–19. Brooklyn: CreateSpace, 2015. ISBN 978-1508721338.

- Obadiah ben Jacob Sforno. Commentary on the Torah. Venice, 1567. Reprinted in, e.g., Sforno: Commentary on the Torah. Translation and explanatory notes by Raphael Pelcovitz, pages 538–49. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1997. ISBN 0-89906-268-7.

- Moshe Alshich. Commentary on the Torah. Safed, circa 1593. Reprinted in, e.g., Moshe Alshich. Midrash of Rabbi Moshe Alshich on the Torah. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 2, pages 659–67. New York, Lambda Publishers, 2000. ISBN 965-7108-13-6.

- Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan, 3:40. England, 1651. Reprint edited by C. B. Macpherson, pages 503–04. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Classics, 1982. ISBN 0-14-043195-0.

- Avraham Yehoshua Heschel. Commentaries on the Torah. Cracow, Poland, mid 17th century. Compiled as Chanukat HaTorah. Edited by Chanoch Henoch Erzohn. Piotrkow, Poland, 1900. Reprinted in Avraham Yehoshua Heschel. Chanukas HaTorah: Mystical Insights of Rav Avraham Yehoshua Heschel on Chumash. Translated by Avraham Peretz Friedman, pages 219–21. Southfield, Michigan: Targum Press/Feldheim Publishers, 2004. ISBN 1-56871-303-7.

- Shabbethai Bass. Sifsei Chachamim. Amsterdam, 1680. Reprinted in, e.g., Sefer Vayikro: From the Five Books of the Torah: Chumash: Targum Okelos: Rashi: Sifsei Chachamim: Yalkut: Haftaros, translated by Avrohom Y. Davis, pages 211–48. Lakewood Township, New Jersey: Metsudah Publications, 2012.

.jpg)

- Chaim ibn Attar. Ohr ha-Chaim. Venice, 1742. Reprinted in Chayim ben Attar. Or Hachayim: Commentary on the Torah. Translated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 3, pages 1057–90. Brooklyn: Lambda Publishers, 1999. ISBN 965-7108-12-8.

- Yitzchak Magriso. Me'am Lo'ez. Constantinople, 1753. Reprinted in Yitzchak Magriso. The Torah Anthology: MeAm Lo'ez. Translated by Aryeh Kaplan, volume 11, pages 275–99. New York: Moznaim Publishing, 1989. ISBN 094011884X.

- Nachman of Breslov. Teachings. Bratslav, Ukraine, before 1811. Reprinted in Rebbe Nachman's Torah: Breslov Insights into the Weekly Torah Reading: Exodus-Leviticus. Compiled by Chaim Kramer; edited by Y. Hall, pages 337–40. Jerusalem: Breslov Research Institute, 2011. ISBN 978-1-928822-53-0.

- Emily Dickinson. Poem 1733 (No man saw awe, nor to his house). 19th century. In The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson. Edited by Thomas H. Johnson, page 703. New York: Little, Brown & Co., 1960. ISBN 0-316-18414-4.

- Samuel David Luzzatto (Shadal). Commentary on the Torah. Padua, 1871. Reprinted in, e.g., Samuel David Luzzatto. Torah Commentary. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 3, pages 934–45. New York: Lambda Publishers, 2012. ISBN 978-965-524-067-2.

- Yehudah Aryeh Leib Alter. Sefat Emet. Góra Kalwaria (Ger), Poland, up to 1905. Excerpted in The Language of Truth: The Torah Commentary of Sefat Emet. Translated and interpreted by Arthur Green, pages 167–72. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1998. ISBN 0-8276-0650-8. Reprinted 2012. ISBN 0-8276-0946-9.

- Alexander Alan Steinbach. Sabbath Queen: Fifty-four Bible Talks to the Young Based on Each Portion of the Pentateuch, pages 84–87. New York: Behrman's Jewish Book House, 1936.

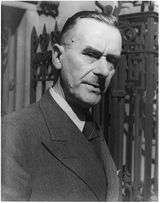

- Thomas Mann. Joseph and His Brothers. Translated by John E. Woods, pages 101, 859. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005. ISBN 1-4000-4001-9. Originally published as Joseph und seine Brüder. Stockholm: Bermann-Fischer Verlag, 1943.

- E.V. Hulse, "The Nature of Biblical ‘Leprosy' and the Use of Alternative Medical Terms in Modern Translations of the Bible." Palestine Exploration Quarterly. Volume 107 (1975): pages 87–105.

- Gordon J. Wenham. The Book of Leviticus, pages 185–203. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1979. ISBN 0-8028-2522-2.

- Walter Jacob. "Jewish Reaction to Epidemics (AIDS)." In Contemporary American Reform Responsa, pages 136–38. New York: Central Conference of American Rabbis, 1987. ISBN 0-88123-003-0.

- Pinchas H. Peli. Torah Today: A Renewed Encounter with Scripture, pages 121–26. Washington, D.C.: B'nai B'rith Books, 1987. ISBN 0-910250-12-X.

- Berit Mila in the Reform Context. Edited by Lewis M. Barth. Berit Mila Board of Reform Judaism, 1990. ISBN 0-8216-5082-3.

- Shaye J. D. Cohen. "Menstruants and the Sacred in Judaism and Christianity." In Women’s History and Ancient History. Edited by Sarah B. Pomeroy, pages 273–99. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991.

- Harvey J. Fields. A Torah Commentary for Our Times: Volume II: Exodus and Leviticus, pages 120–26. New York: UAHC Press, 1991. ISBN 0-8074-0334-2.

- Jacob Milgrom. "The Rationale for Biblical Impurity." Journal of the Ancient Near Eastern Society. Volume 22 (1993): pages 107–11.

- Victor Avigdor Hurowitz. "Review Essay: Ancient Israelite Cult in History, Tradition, and Interpretation." AJS Review, volume 19 (number 2) (1994): pages 213–36.

- Walter C. Kaiser Jr., " The Book of Leviticus," in The New Interpreter's Bible, volume 1, pages 1083–98. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1994. ISBN 0-687-27814-7.

- Judith S. Antonelli. "Childbirth." In In the Image of God: A Feminist Commentary on the Torah, pages 264–75. Northvale, New Jersey: Jason Aronson, 1995. ISBN 1-56821-438-3.

- Ellen Frankel. The Five Books of Miriam: A Woman’s Commentary on the Torah, pages 163–66. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1996. ISBN 0-399-14195-2.

- Lawrence A. Hoffman. Covenant of Blood: Circumcision and Gender in Rabbinic Judaism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996. ISBN 0-226-34783-4.

- W. Gunther Plaut. The Haftarah Commentary, pages 268–76. New York: UAHC Press, 1996. ISBN 0-8074-0551-5.

- Sorel Goldberg Loeb and Barbara Binder Kadden. Teaching Torah: A Treasury of Insights and Activities, pages 183–88. Denver: A.R.E. Publishing, 1997. ISBN 0-86705-041-1.

- Jacob Milgrom. Leviticus 1–16, volume 3, pages 742–826. New York: Anchor Bible, 1998. ISBN 0-385-11434-6.

- Helaine Ettinger. "Our Children/God's Children." In The Women's Torah Commentary: New Insights from Women Rabbis on the 54 Weekly Torah Portions. Edited by Elyse Goldstein, pages 202–10. Woodstock, Vermont: Jewish Lights Publishing, 2000. ISBN 1-58023-076-8.

- Frank H. Gorman Jr. "Leviticus." In The HarperCollins Bible Commentary. Edited by James L. Mays, pages 156–57. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, revised edition, 2000. ISBN 0-06-065548-8.

- Lainie Blum Cogan and Judy Weiss. Teaching Haftarah: Background, Insights, and Strategies, pages 192–99. Denver: A.R.E. Publishing, 2002. ISBN 0-86705-054-3.

- Michael Fishbane. The JPS Bible Commentary: Haftarot, pages 168–78. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2002. ISBN 0-8276-0691-5.

- Robert Alter. The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary, pages 589–98. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2004. ISBN 0-393-01955-1.

- Jacob Milgrom. Leviticus: A Book of Ritual and Ethics: A Continental Commentary, pages 122–32. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2004. ISBN 0-8006-9514-3.

- Baruch J. Schwartz. "Leviticus." In The Jewish Study Bible. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, pages 232–38. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 0-19-529751-2.

- Mary Lande Zamore. "Haftarat Tazri’a: II Kings 4:42–5:19" In The Women's Haftarah Commentary: New Insights from Women Rabbis on the 54 Weekly Haftarah Portions, the 5 Megillot & Special Shabbatot. Edited by Elyse Goldstein, pages 125–29. Woodstock, Vermont: Jewish Lights Publishing, 2004. ISBN 1-58023-133-0.

- Antony Cothey. “Ethics and Holiness in the Theology of Leviticus.” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament, volume 30 (number 2) (December 2005): pages 131–51.

- Professors on the Parashah: Studies on the Weekly Torah Reading Edited by Leib Moscovitz, pages 175–79. Jerusalem: Urim Publications, 2005. ISBN 965-7108-74-8.

- Frank Anthony Spina. "Naaman's Cure, Gehazi's Curse." In The Faith of the Outsider: Exclusion and Inclusion in the Biblical Story, pages 72–93. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2005. ISBN 0-8028-2864-7.

- Calum Carmichael. Illuminating Leviticus: A Study of Its Laws and Institutions in the Light of Biblical Narratives. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006. ISBN 0-8018-8500-0.

- Bernard J. Bamberger. "Leviticus." In The Torah: A Modern Commentary: Revised Edition. Edited by W. Gunther Plaut; revised edition edited by David E.S. Stern, pages 734–49. New York: Union for Reform Judaism, 2006. ISBN 0-8074-0883-2.

- Suzanne A. Brody. "Birthing Contradictions." In Dancing in the White Spaces: The Yearly Torah Cycle and More Poems, page 88. Shelbyville, Kentucky: Wasteland Press, 2007. ISBN 1-60047-112-9.

- James L. Kugel. How To Read the Bible: A Guide to Scripture, Then and Now, page 303. New York: Free Press, 2007. ISBN 0-7432-3586-X.

- Christophe Nihan. From Priestly Torah to Pentateuch: A Study in the Composition of the Book of Leviticus. Coronet Books, 2007. ISBN 3161492579.

- James W. Watts. Ritual and Rhetoric in Leviticus: From Sacrifice to Scripture. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-521-87193-8.

- Tamara Cohn Eskenazi and Andrea L. Weiss, editors. The Torah: A Women's Commentary, pages 637–56. New York: URJ Press, 2008. ISBN 0-8074-1081-0.

- Roy E. Gane. "Leviticus." In Zondervan Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary. Edited by John H. Walton, volume 1, pages 301–02. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 2009. ISBN 978-0-310-25573-4.

- Reuven Hammer. Entering Torah: Prefaces to the Weekly Torah Portion, pages 159–64. New York: Gefen Publishing House, 2009. ISBN 978-965-229-434-0.

- Timothy Keller. "The Seduction of Success." In Counterfeit Gods: The Empty Promises of Money, Sex, and Power, and the Only Hope that Matters. Dutton Adult, 2009. ISBN 0-525-95136-9. (Naaman).