Ki Tavo

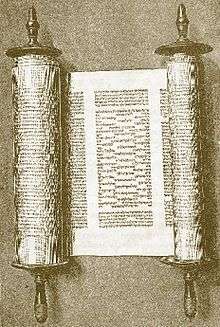

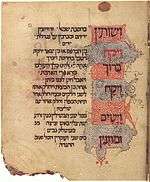

Ki Tavo, Ki Thavo, Ki Tabo, Ki Thabo, or Ki Savo (Hebrew: כִּי-תָבוֹא — Hebrew for "when you enter," the second and third words, and the first distinctive words, in the parashah) is the 50th weekly Torah portion (Hebrew: פָּרָשָׁה, parashah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the seventh in the Book of Deuteronomy. It constitutes Deuteronomy 26:1–29:8. The parashah tells of the ceremony of the first fruits (Hebrew: בִּכּוּרִים, bikkurim), tithes, and the blessings from observance and curses (Hebrew: תוֹכֵחָה, tocheichah) from violation of the law.

The parashah is made up of 6,811 Hebrew letters, 1,747 Hebrew words, 122 verses, and 261 lines in a Torah Scroll (Hebrew: סֵפֶר תּוֹרָה, Sefer Torah).[1] Jews generally read it in September, or rarely in late August.[2]

Readings

In traditional Sabbath Torah reading, the parashah is divided into seven readings, Hebrew: עליות, aliyot. In the Masoretic Text of the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible), Parashah Ki Tavo has four "open portion" (Hebrew: פתוחה, petuchah) divisions (roughly equivalent to paragraphs, often abbreviated with the Hebrew letter Hebrew: פ (peh)). Parashah Ki Tavo has several further subdivisions, called "closed portion" (Hebrew: סתומה, setumah) divisions (abbreviated with the Hebrew letter Hebrew: ס (samekh)) within the open portion divisions. The first open portion spans the first three readings. The second open portion contains all of the fourth and fifth readings and part of the sixth reading. The third open portion constitutes the balance of the sixth reading, which enumerates a series of curses. The fourth open portion is identical with the seventh reading. Closed portion divisions coincide with the first two readings. Closed portion divisions further divide the fourth, fifth, and sixth readings, and a string of 11 closed portion divisions set off a series of curses in the fifth reading.[3]

First reading — Deuteronomy 26:1–11

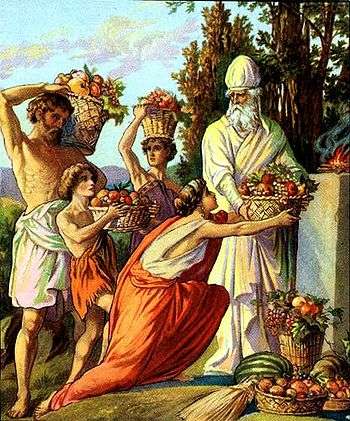

In the first reading (Hebrew: עליה, aliyah), Moses directed the Israelites that when they entered the land that God was giving them, they were to take some of every first fruit of the soil that they harvested, put it in a basket, and take it to the place God would choose.[4] There they were to go to the priest in charge and acknowledge that they had entered the land that God swore to their fathers.[5] The priest was to set the basket down in front of the altar.[6] They were then to recite:

"A wandering Aramean was my father, and he went down into Egypt, and sojourned there, few in number; and he became there a nation, great, mighty, and populous. And the Egyptians dealt ill with us, and afflicted us, and laid upon us hard bondage. And we cried to the Lord, the God of our fathers, and the Lord heard our voice, and saw our affliction, and our toil, and our oppression. And the Lord brought us forth out of Egypt with a mighty hand, and with an outstretched arm, and with great terribleness, and with signs, and with wonders. And He has brought us into this place, and has given us this land, a land flowing with milk and honey. And now, behold, I have brought the first of the fruit of the land, that You, O Lord, have given me."[7]

They were to leave the basket before the altar, bow low to God, and then feast on and enjoy, together with the Levite and the stranger, the bounty that God had given them.[8] The first reading (Hebrew: עליה, aliyah) and a closed portion (Hebrew: סתומה, setumah) end here.[9]

Second reading — Deuteronomy 26:12–15

In the second reading (Hebrew: עליה, aliyah), Moses instructed that when the Israelites had given the tenth part of their yield to the Levite, the stranger, the fatherless, and the widow, in the third year, the year of the tithe, they were to declare before God:

"'I have put away the hallowed things out of my house, and also have given them to the Levite, the stranger, the fatherless, and the widow, according to Your commandment that You have commanded me; I have not transgressed any of Your commandments, neither have I forgotten them. I have not eaten thereof in my mourning, neither have I put away thereof, being unclean, nor given thereof for the dead; I have hearkened to the voice of the Lord my God, I have done according to all that You have commanded me. Look from Your holy habitation, from heaven, and bless Your people Israel, and the land that You have given us, as You swore to our fathers, a land flowing with milk and honey."[10]

The second reading (Hebrew: עליה, aliyah) and a closed portion (Hebrew: סתומה, setumah) end here.[11]

Third reading — Deuteronomy 26:16–19

In the third reading (Hebrew: עליה, aliyah), Moses exhorted the Israelites to observe these laws faithfully with all their heart and soul, noting that they had affirmed that the Lord was their God and that they would obey God.[12] And God affirmed that the Israelites were God's treasured people, and that God would set them high above all the nations in fame and glory, and that they would be a holy people to God.[13] The third reading (Hebrew: עליה, aliyah) and the first open portion (Hebrew: פתוחה, petuchah) end here with the end of chapter 26.[14]

Fourth reading — Deuteronomy 27:1–10

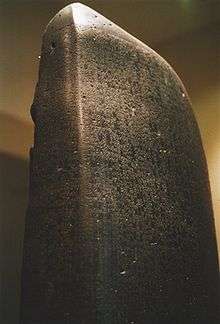

In the fourth reading (Hebrew: עליה, aliyah), Moses and the elders charged the people that as soon as they had crossed the Jordan River, they were to set up large stones on Mount Ebal, coat them with plaster, and inscribe on them all the words of the Torah.[15] There they were also to build an altar to God made of stones on which no iron tool had struck, and they were to offer on it offerings to God and rejoice.[16] A closed portion (Hebrew: סתומה, setumah) ends here with Deuteronomy 27:8.[17]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses and the priests told all Israel to hear: They had become the people of God, and should heed God and observe God's commandments.[18] The fourth reading (Hebrew: עליה, aliyah) and a closed portion (Hebrew: סתומה, setumah) end here.[19]

Fifth reading — Deuteronomy 27:11–28:6

In the fifth reading (Hebrew: עליה, aliyah), Moses charged the people that after they had crossed the Jordan, the tribes of Simeon, Levi, Judah, Issachar, Joseph, and Benjamin were to stand on Mount Gerizim when the blessings were spoken, and the tribes of Reuben, Gad, Asher, Zebulun, Dan, and Naphthali were to stand on Mount Ebal when the curses were spoken.[20] The Levites were then to loudly curse anyone who: made a sculptured image; insulted father or mother; moved a fellow countryman's landmark; misdirected a blind person; subverted the rights of the stranger, the fatherless, or the widow; lay with his father's wife; lay with any beast; lay with his sister; lay with his mother-in-law; struck down his fellow countryman in secret; accepted a bribe in a murder case; or otherwise would not observe the commandments; and for each curse all the people were to say, "Amen."[21] Eleven closed portion (Hebrew: סתומה, setumah) divisions set apart each of the curses, and the curses bring chapter 27 to an end.[22]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses taught that, on the other hand, if the Israelites obeyed God and observed faithfully all the commandments, then God would set them high above all the nations of the earth; bless them in the city and the country; bless the issue of their wombs, the produce of their soil, and the fertility of their herds and flocks; bless their basket and their kneading bowl; and bless them in their comings and goings.[23] The fifth reading (Hebrew: עליה, aliyah) ends here.[24]

Sixth reading — Deuteronomy 28:7–69

In the sixth reading (Hebrew: עליה, aliyah), Moses continued that if the Israelites obeyed God and observed faithfully all the commandments, then God would rout their enemies; bless them upon their barns and all their undertakings; bless them in the land; establish them as God's holy people; give them abounding prosperity; provide rain in season; and make them the head and not the tail.[25] The second open portion (Hebrew: פתוחה, petuchah) ends here.[26]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses taught that if they did not obey God and observe faithfully the commandments, then God would curse them in the city and the country; curse their basket and kneading bowl; curse the issue of their womb, the produce of their soil, and the fertility of their herds and flocks; curse them in their comings and goings; loose on them calamity, panic, and frustration in all their enterprises; make pestilence cling to them; strike them with tuberculosis, fever, inflammation, scorching heat, drought, blight, and mildew; turn the skies into copper and the earth into iron; make the rain into dust; rout them before their enemies; and strike them with the Egyptian inflammation, hemorrhoids, boil-scars, itch, madness, blindness, and dismay.[27] If they paid the bride price for a wife, another man would enjoy her; if they built a house, they would not live in it; if they planted a vineyard, they would not harvest it.[28] Their oxen would be slaughtered before their eyes, but they would not eat of it; their donkey would be seized and not returned; their flock would be delivered to their enemies; their sons and daughters would be delivered to another people; a people they did not know would eat the produce of their soil; they would be abused and downtrodden continually, until they were driven mad; God would afflict them at the knees and thighs with a severe inflammation; God would drive them to an unknown nation where they would serve other gods, of wood and stone; and they would be a byword among all the peoples.[29] Locusts would consume their seed, worms would devour their vineyards, the olives would drop off their olive trees, their sons and daughters would go into captivity, the cricket would take over all the trees and produce of their land, the stranger in their midst would rise above them, the stranger would be their creditor, and the stranger would be the head and they the tail.[30] Because they would not serve God in joy over abundance, they would have to serve in hunger, thirst, and nakedness, the enemies whom God would let loose against them.[31] God would bring against them a ruthless nation from afar, whose language they would not understand, to devour their cattle and produce of their soil and to shut them up in their towns until every mighty wall in which they trusted had come down.[32] And when they were shut up under siege, they would eat the flesh of their sons and daughters.[33] God would inflict extraordinary plagues and diseases on them until they would have a scant few left, for as God once delighted in making them prosperous and many, so would God delight in causing them to perish and diminish.[34] God would scatter them among all the peoples from one end of the earth to the other, but even among those nations, they would find no place to rest.[35] In the morning they would say, "If only it were evening!" and in the evening they would say, "If only it were morning!"[36] God would send them back to Egypt in galleys and they would offer themselves for sale as slaves, but none would buy.[37] The long closed portion (Hebrew: סתומה, setumah) of the curses ends here.[38]

The reading concludes with a summary statement that this is the covenant that God commanded Moses to make with the Israelites in Moab, in addition to the covenant that God made with the Israelites at Horeb (Mount Sinai).[39] The sixth reading (Hebrew: עליה, aliyah) and the third open portion (Hebrew: פתוחה, petuchah) end here with the end of chapter 28.[38]

Seventh reading — Deuteronomy 29:1–8

In the seventh reading (Hebrew: עליה, aliyah), Moses reminded the Israelites that they had seen all that God did to Pharaoh and Egypt, yet they did not yet understand.[40] Moses led them through the wilderness 40 years, their clothes and sandals did not wear out, and they survived without bread to eat and wine to drink, so that they might know that the Lord was their God.[41]

In the maftir (Hebrew: מפטיר) reading of Deuteronomy 29:6–8 that concludes the parashah,[42] Moses recounted that the Israelites defeated King Sihon of Heshbon and King Og of Bashan, took their land, and gave it to the Reubenites, the Gadites, and the half-tribe of Manasseh.[43] Therefore, Moses urged them to observe faithfully all the commandments, that they might succeed in all that they undertook.[44] The seventh reading (Hebrew: עליה, aliyah), the fourth open portion (Hebrew: פתוחה, petuchah), and the parashah end here.[42]

Readings according to the triennial cycle

Jews who read the Torah according to the triennial cycle of Torah reading read the parashah according to the following schedule:[45]

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020, 2023, 2026 ... | 2021, 2024, 2027 ... | 2022, 2025, 2028 ... | |

| Reading | 26:1–27:10 | 26:12–28:6 | 27:11–29:8 |

| 1 | 26:1–3 | 26:12–15 | 27:11–28:3 |

| 2 | 26:4–8 | 26:16–19 | 28:4–6 |

| 3 | 26:9–11 | 27:1–3 | 28:7–11 |

| 4 | 26:12–15 | 27:4–8 | 28:12–14 |

| 5 | 26:16–19 | 27:6–10 | 28:15–69 |

| 6 | 27:1–4 | 27:11–28:3 | 29:1–5 |

| 7 | 27:5–10 | 28:4–6 | 29:6–8 |

| Maftir | 27:7–10 | 28:4–6 | 29:6–8 |

In ancient parallels

The parashah has parallels in these ancient sources:

Deuteronomy chapter 27

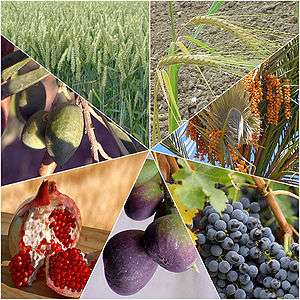

Deuteronomy 27:3 (as well as Exodus 3:8 and 17, 13:5, and 33:3, Leviticus 20:24, Numbers 13:27 and 14:8, and Deuteronomy 6:3, 11:9, 26:9 and 15, and 31:20) describes the Land of Israel as a land flowing "with milk and honey." Similarly, the Middle Egyptian (early second millennium BCE) tale of Sinuhe Palestine described the Land of Israel or, as the Egyptian tale called it, the land of Yaa: "It was a good land called Yaa. Figs were in it and grapes. It had more wine than water. Abundant was its honey, plentiful its oil. All kind of fruit were on its trees. Barley was there and emmer, and no end of cattle of all kinds."[46]

In inner-biblical interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these Biblical sources:[47]

Deuteronomy chapter 26

Professor Benjamin Sommer of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America argued that Deuteronomy 12–26 borrowed whole sections from the earlier text of Exodus 21–23.[48]

Shavuot

Deuteronomy 26:1–11 set out the ceremony for the bringing of the first fruits (Hebrew: בִּכּוּרִים, bikkurim). Exodus 34:22, in turn, associates the Festival of Shavuot with the first fruits (Hebrew: בִּכּוּרֵי, bikurei) of the wheat harvest.[49]

In the Hebrew Bible, Shavuot is called:

- The Feast of Weeks (Hebrew: חַג שָׁבֻעֹת, Chag Shavuot);[50]

- The Day of the first fruits (Hebrew: יוֹם הַבִּכּוּרִים, Yom haBikurim);[51]

- The Feast of Harvest (Hebrew: חַג הַקָּצִיר, Chag haKatzir);[52] and

- A holy convocation (Hebrew: מִקְרָא-קֹדֶשׁ, mikrah kodesh).[53]

To arrive at the correct date, Leviticus 23:15 instructs counting seven weeks from the day after the day of rest of Passover, the day that they brought the sheaf of barley for waving. Similarly, Deuteronomy 16:9 directs counting seven weeks from when they first put the sickle to the standing barley.

Leviticus 23:16–19 sets out a course of offerings for the fiftieth day, including a meal-offering of two loaves made from fine flour from the first fruits of the harvest; burnt-offerings of seven lambs, one bullock, and two rams; a sin-offering of a goat; and a peace-offering of two lambs. Similarly, Numbers 28:26–30 sets out a course of offerings including a meal-offering; burnt-offerings of two bullocks, one ram, and seven lambs; and one goat to make atonement. Deuteronomy 16:10 directs a freewill-offering in relation to God's blessing.

Leviticus 23:21 and Numbers 28:26 ordain a holy convocation in which the Israelites were not to work.

2 Chronicles 8:13 reports that Solomon offered burnt-offerings on the Feast of Weeks.

Corpse contamination

The discussion of the dead in the profession associated with tithing, Deuteronomy 26:13–14, is one of a series of passages setting out the teaching that contact with the dead is antithetical to purity.

In Leviticus 21:1–5, God instructed Moses to direct the priests not to allow themselves to become defiled by contact with the dead, except for a mother, father, son, daughter, brother, or unmarried sister. And the priests were not to engage in mourning rituals of making baldness upon their heads, shaving off the corners of their beards, or cutting their flesh.

In Numbers 5:1–4, God instructed Moses to command the Israelites to put out of the camp every person defiled by contact with the dead, so that they would not defile their camps, in the midst of which God dwelt.

Numbers 19 sets out a procedure for a red cow mixture for decontamination from corpse contamination.

In its profession associated with tithing, Deuteronomy 26:13–14 instructed Israelites to aver that they had not eaten from the tithe in mourning, nor put away any of it while unclean, nor given any of it to the dead.

In Ezekiel 43:6–9, the prophet Ezekiel cites the burial of kings within the Temple as one of the practices that defiled the Temple and cause God to abandon it.

Deuteronomy chapter 27

Deuteronomy 27:5–6, which prohibits wielding iron tools over the stones of the altar and requires that the Israelites build the altar from unhewn stones, echoes Exodus 20:21,[54] which prohibits building the altar from hewn stones, explaining that wielding tools upon the stones would profane them.

Professor John J. Collins of Yale Divinity School noted that Deuteronomy 27–28 describe a ceremony in which the tribes of Israel stand on two mountains that overlook the town of Shechem, and Joshua 24 describes a covenant renewal ceremony at Shechem after the Israelites had occupied the land.[55]

The writing of the law on the plastered stones on Mount Ebal in Deuteronomy 27:8 may be contrasted with the proclamation of the prophet Jeremiah in Jeremiah 31:33, "I will put my law in their minds and write it on their hearts. I will be their God, and they will be my people".

The curse in Deuteronomy 27:18 of one who "makes the blind go astray in the way" echoes the prohibition in Leviticus 19:14 to "put a stumbling-block before the blind."

Deuteronomy chapter 28

The exhortation of Deuteronomy 28:9 to "walk in God's ways" echoes God's injunction to Abraham in Genesis 17:1 and reflects a recurring theme in the discourse of Moses in Deuteronomy 5:30; 8:6; 10:12; 11:22; 19:9; 26:17; and 30:16.

While Leviticus 12:6–8 required a new mother to bring a burnt-offering and a sin-offering, Leviticus 26:9, Deuteronomy 28:11, and Psalm 127:3–5 make clear that having children is a blessing from God; Genesis 15:2 and 1 Samuel 1:5–11 characterize childlessness as a misfortune; and Leviticus 20:20 and Deuteronomy 28:18 threaten childlessness as a punishment.

The curses in Deuteronomy 28:15-68 run in parallel with the Tocheichah curses of Leviticus 26:14–38.

Deuteronomy 28:22 warned, "The Lord will strike you with . . . blight and mildew (Hebrew: בַשִּׁדָּפוֹן, וּבַיֵּרָקוֹן, vashdefon u-vayeirakon)." And in Amos 4:9, the 8th century BCE prophet Amos condemned the people of Israel for not returning to God after God "scourged you with blight and mildew (Hebrew: בַּשִּׁדָּפוֹן וּבַיֵּרָקוֹן, vashidafon u-vayeirakon)."

Deuteronomy 28:62 foretold that the Israelites would be reduced in number after having been as numerous as the stars, echoing God's promise in Genesis 15:5 that Abraham's descendants would as numerous as the stars of heaven. Similarly, in Genesis 22:17, God promised that Abraham's descendants would as numerous as the stars of heaven and the sands on the seashore. In Genesis 26:4, God reminded Isaac that God had promised Abraham that God would make his heirs as numerous as the stars. In Genesis 32:13, Jacob reminded God that God had promised that Jacob's descendants would be as numerous as the sands. In Exodus 32:13, Moses reminded God that God had promised to make the Patriarch's descendants as numerous as the stars. In Deuteronomy 1:10, Moses reported that God had multiplied the Israelites until they were then as numerous as the stars. And in Deuteronomy 10:22, Moses reported that God had made the Israelites as numerous as the stars.

In early nonrabbinic interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these early nonrabbinic sources:[56]

Deuteronomy chapter 27

Philo interpreted the curses of Deuteronomy 27:17–18 regarding moving landmarks and misleading the blind to apply allegorically to virtue and vice. Philo noted that Moses included among his curses (in Deuteronomy 27:17) removing a neighbor's landmark, and Philo interpreted the landmark to represent virtue, which God placed before humankind as the tree of life (in Genesis 2:9) to be a law for the soul. But pleasure, taught Philo, removed this landmark of virtue, placing in its stead the landmark of vice, the tree of death. Philo taught that pleasure was therefore worthy to be cursed, being a passion, which altered the boundaries of the soul, rendering the soul a lover of the passions instead of a lover of virtue. And thus Philo interpreted Genesis 3:14, "And the Lord God said to the serpent, '... You are cursed over every creature and over all the beasts of the field,'" to apply to the passion of pleasure. And Philo read Deuteronomy 27:18, "Cursed is he who causes the blind man to wander in the road," also to speak of pleasure. Philo taught that impious pleasure caused the blind to wander, for the outward sense, devoid of reason, is blinded by nature, and the eyes of its reason are put out. Philo taught that it is by reason alone that we attain a true comprehension of things, and not by the outward senses. Pleasure deceived the outward senses, persuading the outward senses to follow a blind guide, making the mind utterly unable to restrain itself. Only through reason does the mind see clearly, and mischievous things become less formidable in their attacks. But pleasure has put such great artifices in operation to injure the soul that it has compelled the soul to use them as guides, cheating it, and persuading it to exchange virtue for evil habits and vice.[57]

Josephus expounded on the curse in Deuteronomy 27:18 of one who "makes the blind go astray in the way," teaching that one has a duty more generally to show the roads to those who do not know them. And, he taught, one has a duty not to consider it a matter for sport to hinder others by setting them on the wrong way.[58]

Deuteronomy chapter 28

Echoing the command of Deuteronomy 28:14 that the Israelites "shall not turn aside from any of the words which I command you this day, to the right hand, or to the left," the Community Rule of the Qumran sectarians provided, "They shall not depart from any command of God concerning their times; they shall be neither early nor late for any of their appointed times, they shall stray neither to the right nor to the left of any of His true precepts."[59]

.jpg)

In classical rabbinic interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these rabbinic sources from the era of the Mishnah and the Talmud:[60]

Deuteronomy chapter 26

Tractate Bikkurim in the Mishnah, Tosefta, and Jerusalem Talmud interpreted the laws of the first fruits in Exodus 23:19, Numbers 18:13, and Deuteronomy 12:17–18 and 26:1–11.[61]

The Mishnah taught that to set aside first fruits (Hebrew: בִּכּוּרִים, bikkurim), a landowner would go down into the field, see a fruit that ripened, tie a reed-rope around it, and say, "These are first fruits." But Rabbi Simeon said that even if the landowner did this, the landowner still had to designate the fruits as first fruits again after they had been picked.[62]

The Mishnah interpreted the words "the first fruits of your land" in Exodus 23:19 to mean that a person could not bring first fruits (Hebrew: בִּכּוּרִים, bikkurim) unless all the produce came from that person's land. The Mishnah thus taught that people who planted trees but bent their branches into or over another's property could not bring first fruits from those trees. And for the same reason, the Mishnah taught that tenants, lessees, occupiers of confiscated property, or robbers could not bring first fruits.[63]

The Mishnah taught that first fruits (Hebrew: בִּכּוּרִים, bikkurim) were brought only from the Seven Species (Hebrew: שבעת המינים, Shiv'at HaMinim) that Deuteronomy 8:8 noted to praise the Land of Israel: wheat, barley, grapes, figs, pomegranates, olive oil, and date honey. But first fruits could not be brought from dates grown on hills, or from valley-fruits, or from olives that were not of the choice kind. The Mishnah deduced from the words "the feast of harvest, the first fruits of your labors, which you sow in the field" in Exodus 23:16 that first fruits were not to be brought before Shavuot. The Mishnah reported that the men of Mount Zeboim brought their first fruits before Shavuot, but the priests did not accept them, because of what is written in Exodus 23:16.[64]

The Mishnah taught that one who bought two trees in another person's field had to bring the first fruits (Hebrew: בִּכּוּרִים, bikkurim) but did not recite (the declaration of Deuteronomy 26:5–10, which in Deuteronomy 26:10 contains the words, "the land that you, O Lord, have given me," which only those who owned land could recite). Rabbi Meir, however, said that the owner of the two trees had to bring and recite.[65]

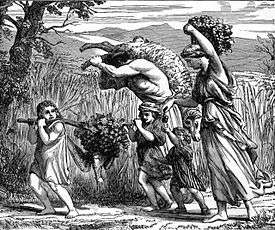

The inhabitants of the district assembled in a city of the district and spent the night in the town square. Early in the morning, their leader said: "Let us rise and go up to Zion, to the house of the Lord our God."[66] Those who lived near Jerusalem brought fresh figs and grapes, and those who lived far away brought dried figs and raisins. Leading the pilgrimage procession was an ox with horns overlaid with gold wearing a crown of olive branches. The sounds of the flute announced the pilgrims' coming until they neared Jerusalem when they sent messengers ahead and arranged their first fruits (Hebrew: בִּכּוּרִים, bikkurim) for presentation. A delegation of the Temple's leaders and treasurers came out to meet them, varying in relation to the procession. Jerusalem's artisans would stand and greet them, saying: "People of such and such a place, we welcome you."[67] They played the flute until they reached the Temple Mount. On the Temple Mount, even King Agrippa would carry the basket of first fruits on his shoulder and walk to the Temple Court. As the procession approached the Temple Court, Levites would sing the words of Psalm 30:2: "I will extol You, O Lord, for You have raised me up, and have not suffered my enemies to rejoice over me."[68]

The pilgrims offered turtle doves that had been tied to the basket as burnt offerings. And they gave what they held in their hands to the priests.[69] While the pilgrims still held the basket on their shoulders, they would recite Deuteronomy 26:3–10. Rabbi Judah said that they read only through Deuteronomy 26:5, "A wandering Aramean was my father." When they reached these words, the pilgrims took the baskets off their shoulders and held them by their edges. The priests would put their hands beneath the baskets and wave them while the pilgrims recited from "A wandering Aramean was my father" through the end of the passage. The pilgrims would then deposit their baskets by the side of the altar, bow, and leave.[70]

The Gemara cited two textual proofs for the instruction of Mishnah Bikkurim 2:4[71] that one waved the first fruits (Hebrew: בִּכּוּרִים, bikkurim). Rabbi Judah interpreted the words "you shall set it down" in Deuteronomy 26:10 to refer to the waving. The Gemara explained that these words could not refer literally to setting the basket down because Deuteronomy 26:4 already accounted for setting the basket down. Alternatively, Rabbi Eliezer ben Jacob deduced the requirement to wave the first fruits from the word "hand" occurring in both Deuteronomy 26:4 and in the case of the peace-offering in Leviticus 7:30, which says, "His own hands shall bring the offering unto the Lord." The Gemara concluded that just as Deuteronomy 26:4 explicitly directs the priest to take the basket and wave it, so in Leviticus 7:30, the priest was to take the offering and wave it, even though Leviticus 7:30 refers only to the donor. And just as Leviticus 7:30 explicitly directs the donor to wave the offering, so in Deuteronomy 26:4, the donor was to wave the basket. The Gemara explained that it was possible for both the priest and the donor to perform the waving because the priest placed his hand under the hand of the donor and they waved the basket together.[72]

Originally, all who knew how to recite would recite, while those unable to do so would repeat after the priest. But when the number of pilgrims declined, it was decided that all pilgrims would repeat the words after the priest.[73]

The Mishnah taught that converts to Judaism would bring the first fruits (Hebrew: בִּכּוּרִים, bikkurim) but not recite, as they could not say the words of Deuteronomy 26:3, "which the Lord swore to our fathers, to give us."[74] But it was taught in a Baraita in the name of Rabbi Judah that even converts both brought first fruits and recited, for when God changed Abram's name to Abraham in Genesis 17:3–5, God made Abraham "the father of a multitude of nations," meaning that Abraham would become the spiritual father of all who would accept the true belief in God.[75]

The rich brought their first fruits (Hebrew: בִּכּוּרִים, bikkurim) in baskets overlaid with silver or gold, while the poor used wicker baskets. Pilgrims would give both the first fruits and the baskets to the priest.[76]

Rabbi Simeon ben Nanos said that the pilgrims could decorate their first fruits (Hebrew: בִּכּוּרִים, bikkurim) with produce other than the seven species, but Rabbi Akiva said that they could decorate only with produce of the seven kinds.[77] Rabbi Simeon taught that there were three elements to the first fruits (Hebrew: בִּכּוּרִים, bikkurim): the first fruits themselves, the additions to the first fruits, and the ornamentations of the first fruits. The additions to the first fruits had to be like the first fruits, but the ornamental fruit could be of another kind. The additions to the first fruits could only be eaten in Levitical purity, and were exempt from the law of doubts as to tithing (demai), but the fruits used for ornamentations were subject to the law of doubts as to tithing.[78]

Rabbi Berekiah in Rabbi Levi's name read Job 29:13 to say, "The blessing of the destroyer (Hebrew: אֹבֵד, oved) came upon me," and interpreted "The blessing of the destroyer (Hebrew: אֹבֵד, oved)" to allude to Laban the Syrian. Rabbi Berekiah in Rabbi Levi's name thus read Deuteronomy 26:5 to say, "An Aramean (Laban) sought to destroy (Hebrew: אֹבֵד, oved) my father (Jacob)." (Thus Laban sought to destroy Jacob by, perhaps among other things, cheating Jacob out of payment for his work, as Jacob recounted in Genesis 31:40–42. This interpretation thus reads Hebrew: אֹבֵד, oved, as a transitive verb.) Rabbi Berekiah and Rabbi Levi in the name of Rabbi Hama ben Haninah thus explained that Rebekah was remembered with the blessing of children only after Isaac prayed for her, so that the heathens in Rebekah's family might not say that their prayer in Genesis 24:60 caused that result. Rather, God answered Isaac's prayer, as Genesis 25:21 reports, "And Isaac entreated the Lord for his wife . . . and his wife Rebekah conceived."[79]

Rabbi Judah the son of Rabbi Simon in the name of Hezekiah employed the meaning of the pilgrim's recitation in Deuteronomy 26:5 to help interpret Jacob's statement to Laban in Genesis 30:30. Rabbi Judah the son of Rabbi Simon noted that the word "little" or "few" (Hebrew: מְעָט, me'at) appears both in Jacob's statement to Laban in Genesis 30:30, "For it was little (Hebrew: מְעָט, me'at) that you had before I came, and it has increased abundantly," and also in the pilgrim's recitation in Deuteronomy 26:5, "few (Hebrew: מְעָט, me'at) in number" (went down to Egypt). Rabbi Judah the son of Rabbi Simon said in the name of Hezekiah that just as in Deuteronomy 26:5, "few" (Hebrew: מְעָט, me'at) means 70 (people), so in Genesis 30:30, "little" (Hebrew: מְעָט, me'at) must also mean 70 (head of cattle and sheep).[80]

The Gemara reported a number of Rabbis' reports of how the Land of Israel did indeed flow with "milk and honey," as described in Exodus 3:8 and 17, 13:5, and 33:3, Leviticus 20:24, Numbers 13:27 and 14:8, and Deuteronomy 6:3, 11:9, 26:9 and 15, 27:3, and 31:20. Once when Rami bar Ezekiel visited Bnei Brak, he saw goats grazing under fig trees while honey was flowing from the figs, and milk dripped from the goats mingling with the fig honey, causing him to remark that it was indeed a land flowing with milk and honey. Rabbi Jacob ben Dostai said that it is about three miles from Lod to Ono, and once he rose up early in the morning and waded all that way up to his ankles in fig honey. Resh Lakish said that he saw the flow of the milk and honey of Sepphoris extend over an area of sixteen miles by sixteen miles. Rabbah bar Bar Hana said that he saw the flow of the milk and honey in all the Land of Israel and the total area was equal to an area of twenty-two parasangs by six parasangs.[81]

Mishnah Peah 8:5–9, Tosefta Peah 4:2–10, and Jerusalem Talmud Peah 69b–73b interpreted Deuteronomy 14:28–29 and 26:12 regarding the tithe given to the poor and the Levite.[82] Noting the words "shall eat and be satisfied" in Deuteronomy 14:29, the Sifre taught that one had to give the poor and the Levite enough to satisfy them.[83] The Mishnah thus taught that they did not give the poor person at the threshing floor less than a half a kav (the equivalent in volume of 12 eggs, or roughly a liter) of wheat or a kav (roughly two liters) of barley.[84] The Mishnah taught that they did not give the poor person wandering from place to place less than a loaf of bread. If the poor person stayed overnight, they gave the poor person enough to pay for a night's lodging. If the poor person stayed for the Sabbath, they gave the poor person three meals.[85] The Mishnah taught that if one wanted to save some for poor relatives, one could take only half for poor relatives and needed to give at least half to other poor people.[86]

In the Sifre, the Sages taught that the time for the removal of tithes specified in Deuteronomy 26:12–13 was the closing Festival day of Passover in the fourth and seventh years.[87]

A Midrash interpreted the command of Deuteronomy 26:12 to give "to the Levite, to the stranger, to the orphan, and to the widow" in the light of Proverbs 22:22, which says, "Rob not the weak, because he is weak, neither crush the poor in the gate." And the Midrash taught that if one did "crush the poor" by failing to give the tithe, in the words of Proverbs 22:23, "the Lord will plead their cause, and despoil of life those that despoil them."[88]

Noting that the discussion of gifts to the poor in Leviticus 23:22 appears between discussions of the festivals — Passover and Shavuot on one side, and Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur on the other — Rabbi Avardimos ben Rabbi Yossi said that this teaches that people who give immature clusters of grapes (as in Leviticus 19:10 and Deuteronomy 24:21), the forgotten sheaf (as in Deuteronomy 24:19), the corner of the field (as in Leviticus 19:9 and 23:22), and the poor tithe (as in Deuteronomy 14:28 and 26:12) is accounted as if the Temple existed and they offered up their sacrifices in it. And for those who do not give to the poor, it is accounted to them as if the Temple existed and they did not offer up their sacrifices in it.[89]

The Mishnah taught that the pilgrim could say the confession over the tithe in Deuteronomy 26:13–15 in any language[90] and anytime during the day.[91]

The Mishnah recounted that Johanan the High Priest abolished the confession over the tithe.[92] Rabbi Jose bar Hanina reported that Johanan the High Priest did so because people were not presenting the tithe as mandated by the Torah. For God commanded that the Israelites should give it to the Levites, but (since the days of Ezra) they presented it to the priests instead.[93]

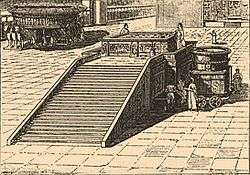

Deuteronomy chapter 27

The Mishnah told that the stones of the Temple's altar and ramp came from the valley of Beit Kerem. When retrieving the stones, they dug virgin soil below the stones and brought whole stones that iron never touched, as required by Deuteronomy 27:5–6, because iron rendered stones unfit for the altar just by touch. A stone was also unfit if it was chipped through any means. They whitewashed the walls and top of the altar twice a year, on Passover and Sukkot, and they whitewashed the vestibule once a year, on Passover. Rabbi (Judah the Patriarch) said that they cleaned them with a cloth every Friday because of blood stains. They did not apply the whitewash with an iron trowel, out of the concern that the iron trowel would touch the stones and render them unfit, for iron was created to shorten humanity's days, and the altar was created to extend humanity's days, and it is not proper that that which shortens humanity's days be placed on that which extends humanity's days.[94]

The Tosefta reported that Rabban Joḥanan ben Zakkai said that Deuteronomy 27:5 singled out iron, of all metals, to be invalid for use in building the altar because one can make a sword from it. The sword is a sign of punishment, and the altar is a sign of atonement. They thus kept that which is a sign of punishment away from that which is a sign of atonement. Because stones, which do not hear or speak, bring atonement between Israel and God, Deuteronomy 27:5 says, "you shall lift up no iron tool upon them." So children of Torah, who atone for the world — how much more should no force of injury come near to them.[95] Similarly, Deuteronomy 27:6 says, "You shall build the altar of the Lord your God of unhewn stones." Because the stones of the altar secure the bond between Israel and God, God said that they should be whole before God. Children of Torah, who are whole for all time — how much more should they be deemed whole (and not wanting) before God.[96]

Rabbi Judah ben Bathyra taught that in the days of the Temple in Jerusalem, Jews could not rejoice without meat (from an offering), as Deuteronomy 27:7 says, "And you shall sacrifice peace-offerings, and shall eat there; and you shall rejoice before the Lord your God." But now that the Temple no longer exists, Jews cannot rejoice without wine, as Psalm 105:15 says, "And wine gladdens the heart of man."[97]

Reading Deuteronomy 1:5, "Beyond the Jordan, in the land of Moab, Moses took upon himself to expound (בֵּאֵר, be’er) this law," the Gemara noted the use of the same word as in Deuteronomy 27:8 with regard to the commandment to erect the stones on Mount Ebal, "And you shall write on the stones all the words of this law clearly elucidated (בַּאֵר, ba’er)." The Gemara reasoned through a verbal analogy that Moses also wrote down the Torah on stones in the land of Moab and erected them there. The Gemara concluded that there were thus three sets of stones so inscribed. Rabbi Judah taught that the Israelites inscribed the Torah on the stones, as Deuteronomy 27:8 says, "You shall write upon the stones all the words of this law," and after that they plastered them over with plaster. Rabbi Simeon asked Rabbi Judah how then the people of that time learned the Torah (as the inscription would have been covered with plaster). Rabbi Judah replied that God endowed the people of that time with exceptional intelligence, and they sent their scribes, who peeled off the plaster and carried away a copy of the inscription. On that account, the verdict was sealed for them to descend into the pit of destruction, because it was their duty to learn Torah, but they failed to do so. Rabbi Simeon, however, taught that the Israelites inscribed the Torah on the plaster and wrote below (for the nations) the words of Deuteronomy 20:18, "That they teach you not to do after all their abominations." And Rabbi Simeon taught that if people of the nations then repented, they would be accepted. Rava bar Shila taught that Rabbi Simeon's reason for teaching that the Israelites inscribed the Torah on the plaster was because Isaiah 33:12 says, "And the peoples shall be as the burnings of plaster." That is, the people of the other nations would burn on account of the matter on the plaster (and because they failed to follow the teachings written on the plaster). Rabbi Judah, however, explained Isaiah 33:12 to mean that their destruction would be like plaster: Just as there is no other remedy for plaster except burning (for burning is the only way to obtain plaster), so there was no remedy for those nations (who cleave to their abominations) other than burning.[98]

Rabbi Judah expounded the words of Deuteronomy 27:9, "Attend and hear, O Israel: This day you have become a people unto the Lord your God." Rabbi Judah asked whether it was on that day that the Torah was given to Israel; was that day not at the end of the 40 years of the wandering in the Wilderness? Rabbi Judah explained that the words "this day" served to teach that every day the Torah is as beloved to those who study it as on the day when God gave it at Mount Sinai. The Gemara explained that the word "attend" (Hebrew: הַסְכֵּת, hasket) in Deuteronomy 27:9 teaches that students should form groups (aso kitot) to study the Torah, as one can acquire knowledge of the Torah only in association with others, and this is in accord with what Rabbi Jose ben Hanina said when he interpreted the words of Jeremiah 50:36, "A sword is upon the boasters (Hebrew: בַּדִּים, baddim) and they shall become fools," to mean that a sword is upon the scholars who sit separately (bad bebad) to study the Torah. The Gemara offered another explanation of the word "attend" (Hebrew: הַסְכֵּת, hasket) in Deuteronomy 27:9 to mean, "be silent" (has) listening to the lesson, and then "analyze" (katet), as Rava taught that a person should always first learn Torah, and then scrutinize it.[99]

Our Rabbis asked in a Baraita why Deuteronomy 11:29 says, "You shall set the blessing upon Mount Gerizim and the curse upon mount Ebal." Deuteronomy 11:29 cannot say so merely to teach where the Israelites were to say the blessings and curses, as Deuteronomy 27:12–13 already says, "These shall stand upon Mount Gerizim to bless the people . . . and these shall stand upon Mount Ebal for the curse." Rather, the Rabbis taught that the purpose of Deuteronomy 11:29 was to indicate that the blessings must precede the curses. It is possible to think that all the blessings must precede all the curses; therefore, the text states "blessing" and "curse" in the singular, and thus teaches that one blessing precedes one curse, alternating blessings and curses, and all the blessings do not proceed all the curses. A further purpose of Deuteronomy 11:29 is to draw a comparison between blessings and curses: As the curse was pronounced by the Levites, so the blessing had to be pronounced by the Levites. As the curse was uttered in a loud voice, so the blessing had to be uttered in a loud voice. As the curse was said in Hebrew, so the blessing had to be said in Hebrew. As the curses were in general and particular terms, so must the blessings had to be in general and particular terms. And as with the curse, both parties respond "Amen," so with the blessing both parties respond "Amen."[100]

The Mishnah told how the Levites pronounced the blessings and curses. When the Israelites crossed the Jordan and came to Mount Gerizim and Mount Ebal, six tribes ascended Mount Gerizim and six tribes ascended Mount Ebal. The priests and Levites with the Ark of the Covenant stationed themselves below in the center. The priests surrounded the Ark, the Levites surrounded the priests, and all the Israelites stood on this side and that of the Levites, as Joshua 8:33 says, "And all Israel, and their elders and officers, and their judges stood on this side the ark and on that side." The Levites turned their faces towards Mount Gerizim and opened with the blessing: "Blessed be the man who does not make a graven or molten image," and all the Israelites responded, "Amen." Then the Levites turned their faces towards Mount Ebal and opened with the curse of Deuteronomy 27:15: "Cursed be the man who makes a graven or molten image," and all the Israelites responded, "Amen." So they continued until they had completed all the blessings and curses.[101]

.jpg)

Rabbi Judah ben Nahmani, the interpreter of Simeon ben Lakish (Resh Lakish), taught that the whole section of the blessings and curses refers to adultery. Deuteronomy 27:15 says, "Cursed be the man who makes a graven or molten image." Is it enough merely to curse such a person in this world? Rather, Rabbi Judah ben Naḥmani taught that Deuteronomy 27:15 alludes to one who commits adultery and has a son who goes to live among idolaters and worships idols; cursed be the father and mother of this man, as they were the cause of his sinning.[100]

A Midrash noted that almost everywhere, including Deuteronomy 27:16, Scripture mentions a father's honor before the mother's honor.[102] But Leviticus 19:3 mentions the mother first to teach that one should honor both parents equally.[103]

Rabbi Eliezer the Great taught that the Torah warns against wronging a stranger in 36, or others say 46, places (including Deuteronomy 27:19).[104] The Gemara went on to cite Rabbi Nathan's interpretation of Exodus 22:20, "You shall neither wrong a stranger, nor oppress him; for you were strangers in the land of Egypt," to teach that one must not taunt one's neighbor about a flaw that one has oneself. The Gemara taught that thus a proverb says: If there is a case of hanging in a person's family history, do not say to the person, "Hang up this fish for me."[105]

The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer read the curse of Deuteronomy 27:24, "Cursed be he that smites his neighbor in secret," to teach that one must not slander. According to the Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer, anyone who secretly slanders a neighbor has no remedy, as Psalm 101:5 says, "Whoso privately slanders his neighbor, him will I destroy: him that has a high look and a proud heart will I not suffer."[106]

Rabbi Aha said in the name of Rabbi Tanhum that if a person studies Torah and teaches it, observes and performs its precepts, but has the means to support needy scholars and fails to do so, then that person comes within the words of Deuteronomy 27:26: "Cursed be he who does not confirm the words of this law." But if a person studies and does not teach or observe or perform the precepts, and does not have the means to support needy scholars and yet does so by self-denial, then that person comes within the category of "Blessed be he who confirms the words of this law," for every "cursed" implies a "blessed."[107] Similarly, a Midrash taught that had Deuteronomy 27:26 read, "Cursed be he who does not learn the words of the law," then Israel would not have been able to survive, but Deuteronomy 27:26 reads, "who does not confirm the words of this law," and so the Hebrew implies that one may avoid the curse through the maintenance of Torah students and colleges.[108]

A Midrash taught that there is nothing greater before God than the "amen" that Israel answers. Rabbi Judah ben Sima taught that the word "amen" contains three kinds of solemn declarations: oath, consent, and confirmation. Numbers 5:21–22 demonstrates oath when it says, "Then the priest shall cause the woman to swear . . . and the woman shall say: 'Amen, Amen.'" Deuteronomy 27:26 demonstrates consent when it says "And all the people shall say: 'Amen.'" And 1 Kings 1:36 demonstrates confirmation when it says, "And Benaiah the son of Jehoiada answered the king, and said: 'Amen; so say the Lord.'"[109]

The Mishnah told that after they had completed all the blessings and curses, the Israelites brought the stones that Moses directed them to set up in Deuteronomy 27:2–4, built the altar and plastered it with plaster, and inscribed on it all the words of the Torah in 70 languages, as Deuteronomy 27:8 says, "very plainly." Then they took the stones and spent the night in their place.[110]

Deuteronomy chapter 28

The Mishnah taught that they read the blessings and curses of Leviticus 26:3–45 and Deuteronomy 28:1–68 on public fast days. The Mishnah taught that they did not interrupt the reading of the curses, but had one person read them all.[111] In the Babylonian Talmud, however, Abaye taught that this rule applies only with regard to the curses in Leviticus 26, but with regard to the curses in Deuteronomy 28, one may interrupt them and have two different people read them. The Gemara explained this distinction by noting that the curses in Leviticus are stated in the plural, and Moses pronounced them from the mouth God, and as such, they are more severe. The curses in Deuteronomy, however, are stated in the singular, and Moses said them on his own, like the rest of the book of Deuteronomy, and are thus considered less harsh.[112]</ref>

A Midrash interpreted Deuteronomy 28:1 to teach that Moses told Israel to be diligent to listen to the words of the Torah, because whoever listens to the words of the Torah is exalted in both this world and the World to Come.[113] Another Midrash tied Deuteronomy 28:1, "And it shall come to pass, if you shall listen diligently," to Proverbs 8:34–35, "Happy is the man who listens to me . . . for whoever finds Me finds life, and obtains favor of the Lord." And the Midrash interpreted Proverbs 8:34 to mean that a person is happy whose hearing is devoted to God.[114]

_-_The_Olive_Trees_(1889).jpg)

Reading the words "to observe to do all His commandments" in Deuteronomy 28:1, Rabbi Simeon ben Halafta taught that one who learns the words of the Torah and does not fulfill them receives punishment more severe than does the one who has not learned at all.[115]

A Midrash expounded on why Israel was, in the words of Jeremiah 11:16, like "a leafy olive tree." In one explanation, the Midrash taught that just as oil floats to the top even after it has been mixed with every kind of liquid, so Israel, as long as it performs the will of God, will be set on high by God, as it says in Deuteronomy 28:1.[116]

Rabbi Joshua of Siknin in the name of Rabbi Levi interpreted Deuteronomy 28:1 to convey God's message that if people will heed God's commandments, God will heed their prayers.[117]

Rav's disciples told Rabbi Abba that Rav interpreted the words of Deuteronomy 28:3, "Blessed shall you be in the city," to mean that your house would be near a synagogue. Rav interpreted the words, "and blessed shall you be in the field," to mean that your property would be near the city. Rav interpreted the words of Deuteronomy 28:6, "Blessed shall you be when you come in," to mean that you would not find your wife in doubt of being a niddah upon returning home from travels. And Rav interpreted the words, "and blessed shall you be when you go out," to mean that your children would be like you. Rabbi Abba replied that Rabbi Joḥanan interpreted the words of Deuteronomy 28:3, "Blessed shall you be in the city," to mean that the privy, not the synagogue, would be near at hand. Rabbi Johanan's interpretation was in accordance with his opinion that one receives reward for walking (some distance) to a synagogue. Rabbi Johanan interpreted the words, "And blessed shall you be in the field," to mean that your estate would be divided into three equal portions of cereals, olives, and vines.[118]

Rabbi Isaac interpreted the words of Deuteronomy 28:3, "Blessed shall you be in the city," to mean that God will reward people for the commandments that they fulfil in the city — the dough offering (Hebrew: חלה, challah),[119] the fringes (Hebrew: ציצית, tzitzit),[120] the sukkah,[121] and the kindling of Shabbat candles.[122] And the continuation of Deuteronomy 28:3, "And blessed shall you be in the field," means that God will reward for the precepts people fulfil in the field — the gleanings in the field that belong to the poor (leket),[123] the forgotten sheaf in the field that belongs to the poor (shikhah),[124] and the corner of the field left unreaped for the poor (Hebrew: פֵּאָה, peah),[125] And the Rabbis interpreted Deuteronomy 28:3 to mean that people will feel blessed in the city because they have been blessed through the field, the earth having yielded its fruits.[126]

Rabbi Johanan interpreted the words of Deuteronomy 28:6, "Blessed shall you be when you come in, and blessed shall you be when you go out," to mean that your exit from the world would be as your entry to it — and just as you entered the world without sin, so would you leave it without sin.[127]

Rabbi Judah bar Simon read Deuteronomy 28:6, "Blessed shall you be when you come in, and blessed shall you be when you go out," to refer to Moses. Rabbi Judah bar Simon read "when you come in" to refer to Moses, because when he came into the world, he brought nearer to God Batya the daughter of Pharaoh (who by saving Moses from drowning merited life in the World to Come). And "blessed shall you be when you go out" also refers to Moses, for as he was departing the world, he brought Reuben nearer to his estranged father Jacob, when Moses blessed Reuben with the words "Let Reuben live and not die" in Deuteronomy 33:6 (thus gaining for Reuben the life in the World to Come and thus proximity to Jacob that Reuben forfeited when he sinned against his father in Genesis 35:22 and became estranged from him in Genesis 49:4).[128]

Rabbi Abba bar Kahana read Deuteronomy 28:1–69 together with Proverbs 2:1, "And lay up my commandments with you," to teach God's message that if people laid up for God Torah and precepts in this world, then God would lay up for them a good reward in the World to Come.[129]

And Ben Azzai taught that the performance of one commandment leads to the performance of another commandment, and one sin leads to another sin; and thus the reward for a commandment is another commandment, and the reward for one sin is another sin.[130]

The Sifre interpreted the "ways" of God referred to in Deuteronomy 28:9 (as well as Deuteronomy 5:30; 8:6; 10:12; 11:22; 19:9; 26:17; and 30:16) by making reference to Exodus 34:6–7, "The Lord, the Lord, God of mercy and grace, slow to wrath and abundant in mercy and truth, keeping lovingkindness for thousands, forgiving transgression, offense, and sin, and cleansing . . . ." Thus the Sifre read Joel 3:5, "All who will be called by the name of the Lord shall be delivered," to teach that just as Exodus 34:6 calls God "merciful and gracious," we, too, should be merciful and gracious. And just as Psalm 11:7 says, "The Lord is righteous," we, too, should be righteous.[131]

Rabbi Abin son of Rav Ada in the name of Rabbi Isaac deduced from Deuteronomy 28:10 that God wears tefillin. For Isaiah 62:8 says: "The Lord has sworn by His right hand, and by the arm of His strength." "By His right hand" refers to the Torah, for Deuteronomy 33:2 says, "At His right hand was a fiery law to them." "And by the arm of His strength" refers to tefillin, as Psalm 29:11 says, "The Lord will give strength to His people," and tefillin are a strength to Israel, for Deuteronomy 28:10 says, "And all the peoples of the earth shall see that the name of the Lord is called upon you, and they shall be afraid of You," and Rabbi Eliezer the Great said that this refers to tefillin of the head (in which the Name of God is written in fulfillment of Deuteronomy 28:10).[132]

A Baraita taught that having observed that Deuteronomy 28:36 predicted, "The Lord will bring you and your king . . . to a nation that you have not known," Josiah ordered the Ark referred to in Exodus 37:1–5 hidden away, as 2 Chronicles 35:3 reports, "And he [Josiah] said to the Levites who taught all Israel, that were holy to the Lord, 'Put the Holy Ark into the house that Solomon the son of David, King of Israel, built; there shall no more be a burden upon your shoulders; now serve the Lord your God and his people Israel.'" The Baraita further taught that at the same time Josiah hid away the Ark, he also hid the jar of manna referred to in Exodus 16:33, the anointing oil referred to in Exodus 30:22–33, Aaron's rod with its almonds and blossoms referred to in Numbers 17:23, and the coffer that the Philistines sent the Israelites as a gift along with the Ark and concerning which the priests said in 1 Samuel 6:8, "And put the jewels of gold, which you returned Him for a guilt offering, in a coffer by the side thereof [of the Ark]; and send it away that it may go." Rabbi Eleazar deduced that Josiah hid the anointing oil and the other objects at the same time as the Ark from the common use of the expressions "there" in Exodus 16:33 with regard to the manna and "there" in Exodus 30:6 with regard to the Ark, "to be kept" in Exodus 16:33 with regard to the manna and "to be kept" in Numbers 17:25 with regard to Aaron's rod, and "generations" in Exodus 16:33 with regard to the manna and "generations" in Exodus 30:31 with regard to the anointing oil.[133]

The curse of Deuteronomy 28:48 figured in a debate among the Rabbis about whether one should perform a worldly occupation in addition to studying Torah. The Rabbis in a Baraita questioned what was to be learned from the words of Deuteronomy 11:14: "And you shall gather in your corn and wine and oil." Rabbi Ishmael replied that since Joshua 1:8 says, "This book of the law shall not depart out of your mouth, but you shall meditate therein day and night," one might think that one must take this injunction literally (and study Torah every waking moment). Therefore, Deuteronomy 11:14 directs one to "gather in your corn," implying that one should combine Torah study with a worldly occupation. Rabbi Simeon ben Yoḥai questioned that, however, asking if a person plows in plowing season, sows in sowing season, reaps in reaping season, threshes in threshing season, and winnows in the season of wind, when would one find time for Torah? Rather, Rabbi Simeon ben Yoḥai taught that when Israel performs God's will, others perform its worldly work, as Isaiah 61:5–6 says, "And strangers shall stand and feed your flocks, aliens shall be your plowmen and vine-trimmers; while you shall be called 'Priests of the Lord,' and termed 'Servants of our God.'" And when Israel does not perform God's will, it has to carry out its worldly work by itself, as Deuteronomy 11:14 says, "And you shall gather in your corn." And not only that, but the Israelites would also do the work of others, as Deuteronomy 28:48 says, "And you shall serve your enemy whom the Lord will let loose against you. He will put an iron yoke upon your neck until He has wiped you out." Abaye observed that many had followed Rabbi Ishmael's advice to combine secular work and Torah study and it worked well, while others have followed the advice of Rabbi Simeon ben Yoḥai to devote themselves exclusively to Torah study and not succeeded. Rava would ask the Rabbis (his disciples) not to appear before him during Nisan (when corn ripened) and Tishrei (when people pressed grapes and olives) so that they might not be anxious about their food supply during the rest of the year.[134]

The Mishnah taught that when they flogged a person, a reader would read Deuteronomy 28:58ff, beginning "If you will not observe to do all the words of this law that are written in this book . . . ," then Deuteronomy 29:8, "Observe therefore the words of this covenant," and then Psalm 78:38, "But He, being full of compassion, forgives iniquity."[135]

Rabbi Johanan taught that God does not rejoice in the downfall of the wicked. Rabbi Johanan interpreted the words zeh el zeh in the phrase "And one did not come near the other all the night" in Exodus 14:20 to teach that when the Egyptians were drowning in the sea, the ministering angels wanted to sing a song of rejoicing, as Isaiah 6:3 associates the words zeh el zeh with angelic singing. But God rebuked them: "The work of my hands is being drowned in the sea, and you want to sing songs?" Rabbi Eleazar replied that a close reading of Deuteronomy 28:63 shows that God does not rejoice personally, but does make others rejoice.[136]

Rabban Simeon ben Gamliel said in the name of Rabbi Joshua that from the day that the Temple was destroyed, there was no day without a curse, the dew had not descended for a blessing, and the flavor had departed from fruits.[137] Rava said that in addition, the curse of each day was severer than that of the preceding day, as Deuteronomy 28:67 says, "In the morning, you shall say: Would God it were evening! And in the evening, you shall say: Would God it were morning." The Gemara asked which morning they would long for. If it would be the morning of the next day, nobody knows what that will be like. Therefore, reasoned the Gemara, it must have been the morning of the previous day (because the previous day would have been less severe than the current day, and therefore they longed for its return).[138]

In Deuteronomy 28:67, the heart fears. A Midrash catalogued the wide range of additional capabilities of the heart reported in the Hebrew Bible.[139] The heart speaks,[140] sees,[140] hears,[141] walks,[142] falls,[143] stands,[144] rejoices,[145] cries,[146] is comforted,[147] is troubled,[148] becomes hardened,[149] grows faint,[150] grieves,[151] can be broken,[152] becomes proud,[153] rebels,[154] invents,[155] cavils,[156] overflows,[157] devises,[158] desires,[159] goes astray,[160] lusts,[161] is refreshed,[162] can be stolen,[163] is humbled,[164] is enticed,[165] errs,[166] trembles,[167] is awakened,[168] loves,[169] hates,[170] envies,[171] is searched,[172] is rent,[173] meditates,[174] is like a fire,[175] is like a stone,[176] turns in repentance,[177] becomes hot,[178] dies,[179] melts,[180] takes in words,[181] is susceptible to fear,[182] gives thanks,[183] covets,[184] becomes hard,[185] makes merry,[186] acts deceitfully,[187] speaks from out of itself,[188] loves bribes,[189] writes words,[190] plans,[191] receives commandments,[192] acts with pride,[193] makes arrangements,[194] and aggrandizes itself.[195]

Deuteronomy chapter 29

Reading Deuteronomy 29:4, "Your clothes have not grown old on you," Rabbi Jose bar Ḥanina taught that the clothes that the Israelites wore did not wear out, but those that they packed away in their trunks did.[196] Alternatively, Rabbi Eleazar, the son of Rabbi Simeon ben Yoḥai, asked his father-in-law Rabbi Simeon ben Jose whether the Israelites had not taken with them leather garments into the wilderness (which would wear out). Rabbi Simeon ben Jose replied that the clothes that they wore were those with which the ministering angels had invested them at Mount Sinai, and therefore they did not grow old. Rabbi Eleazar asked whether the Israelites did not grow so that the clothes became too small for them. Rabbi Simeon ben Jose replied that one should not wonder at this, for when a snail grows, its shell grows with it. Rabbi Eleazar asked whether the clothes did not need washing. Rabbi Simeon ben Jose replied that the pillar of cloud rubbed against them and whitened them. Rabbi Eleazar asked whether they were not scorched, as the cloud consisted of fire. Rabbi Simeon ben Jose replied that one should not wonder at this, as amianthus (a kind of asbestos) is cleansed only by fire, and as their clothes were made in heaven, the cloud rubbed against them without damaging them. Rabbi Eleazar asked whether vermin did not breed in the clothes. Rabbi Simeon ben Jose replied that if in their death no worm could touch the Israelites, how much less could vermin in their lifetime. Rabbi Eleazar asked whether they did not smell because of perspiration. Rabbi Simeon ben Jose replied that they used to play with the sweet-scented grass around the well, as Song 4:11 says, "And the smell of your garments is like the smell of Lebanon."[197]

Rabbi Eleazar interpreted the words, "Keep therefore the words of this covenant, and make them," in Deuteronomy 29:8 to teach that Scripture regards one who teaches Torah to a neighbor's child as though he himself had created the words of the Torah, as it is written.[198]

Rabbi Joshua ben Levi noted that the promise of Deuteronomy 29:8 that whoever studies the Torah prospers materially is written in the Torah, the Prophets (Hebrew: נְבִיאִים, Nevi'im), and the Writings (Hebrew: כְּתוּבִים, Ketuvim). In the Torah, Deuteronomy 29:8 says: "Observe therefore the words of this covenant, and do them, that you may make all that you do to prosper." It is repeated in the Prophets in Joshua 1:8, "This book of the Law shall not depart out of your mouth, but you shall meditate therein day and night, that you may observe to do according to all that is written therein; for then you shall make your ways prosperous, and then you shall have good success." And it is mentioned a third time in the Writings in Psalm 1:2–3, "But his delight is in the Law of the Lord, and in His Law does he meditate day and night. And he shall be like a tree planted by streams of water, that brings forth its fruit in its season, and whose leaf does not wither; and in whatever he does he shall prosper."[199]

Rabbi Berekiah interpreted Lamentations 3:1, "I am the man (Hebrew: גֶּבֶר, gever) who has seen affliction by the rod of His wrath," to mean that God strengthened the writer (writing for the people of God) to withstand all afflictions (interpreting Hebrew: גֶּבֶר, gever, "man," to mean Hebrew: גִּבֹּר, gibor, "strong man"). Rabbi Berekiah noted that after the 98 reproofs in Deuteronomy 28:15–68, Deuteronomy 29:9 says, "You are standing this day all of you," which Rabbi Berekiah taught we render (according to Onkelos), "You endure this day all of you," and thus to mean, you are strong men to withstand all these reproofs.[200]

In medieval Jewish interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these medieval Jewish sources:[201]

Deuteronomy chapter 26

In his letter to Obadiah the Proselyte, Maimonides addressed whether a convert could recite declarations like that in Deuteronomy 26:3, "A wandering Aramean was my father." Maimonides wrote that converts may say such declarations in the prescribed order and not change them in the least, and may bless and pray in the same way as every Jew by birth. Maimonides reasoned that Abraham taught the people, brought many under the wings of the Divine Presence, and ordered members of his household after him to keep God's ways forever. As God said of Abraham in Genesis 18:19, "I have known him to the end that he may command his children and his household after him, that they may keep the way of the Lord, to do righteousness and justice." Ever since then, Maimonides taught, whoever adopts Judaism is counted among the disciples of Abraham. They are Abraham's household, and Abraham converted them to righteousness. In the same way that Abraham converted his contemporaries, he converts future generations through the testament that he left behind him. Thus Abraham is the father of his posterity who keep his ways and of all proselytes who adopt Judaism. Therefore, Maimonides counseled converts to pray, "God of our fathers," because Abraham is their father. They should pray, "You who have taken for his own our fathers," for God gave the land to Abraham when in Genesis 13:17, God said, "Arise, walk through the land in the length of it and in the breadth of it; for I will give to you." Maimonides concluded that there is no difference between converts and born Jews. Both should say the blessing, "Who has chosen us," "Who has given us," "Who have taken us for Your own," and "Who has separated us"; for God has chosen converts and separated them from the nations and given them the Torah. For the Torah has been given to born Jews and proselytes alike, as Numbers 15:15 says, "One ordinance shall be both for you of the congregation, and also for the stranger that sojourns with you, an ordinance forever in your generations; as you are, so shall the stranger be before the Lord." Maimonides counseled converts not to consider their origin as inferior. While born Jews descend from Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, converts derive from God, through whose word the world was created. As Isaiah said in Isaiah 44:5: "One shall say, I am the Lord's, and another shall call himself by the name of Jacob."[202]

Reading Deuteronomy 26:12, "And they shall eat in your gates and be satisfied," Maimonides taught that when poor people passed by a field while the owner was in the field and in possession of the tithe for the poor, the owner had to give each poor person who passed a portion of the tithe sufficient to satisfy the poor person.[203]

Deuteronomy chapter 28

Maimonides taught that because idolatrous religions promised great reward in length of life, protection from illness, exemption from bodily deformities, and plenty of produce, Scripture teaches, in order that people should abandon idolatry, that blessings actually flow from the reverse of what the idolatrous priests preached to the people.[204]

Maimonides interpreted Deuteronomy 28:9, "And you shall walk in His ways," to command a person to walk in intermediate paths, near the midpoint between extremes of character.[205] And Maimonides reported that the Sages explained the commandment of Deuteronomy 28:9 to teach that just as God is called "Gracious," one should be gracious; just as God is called "Merciful," one should be merciful; just as God is called "Holy," one should be holy; and just as the prophets called God "Slow to anger," "Abundant in kindness," "Righteous," "Just," "Perfect," "Almighty," "Powerful," and the like, one is obligated to accustom oneself to these paths and to try to resemble God to the extent of one's ability.[206]

Baḥya ibn Paquda read Deuteronomy 28:58, "that you may fear this glorious and revered Name," as an example of how Scripture ascribes most of its praises to the "Name" of God, as it is impossible to form a representation of God with the intellect or picture God with the imagination. Scripture thus honors and exalts God’s essence because, besides apprehending that God exists, it is impossible for people to conceive in our minds anything about God’s Being except for God’s great Name. Baḥya noted that for this reason, the Torah frequently repeats God’s Name.[207]

In modern interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these modern sources:

Deuteronomy chapters 11–29

The 20th century scholar Peter Craigie, formerly of the University of Calgary, saw in Deuteronomy 11:26–29:1 the following chiastic structure centered on the specific legislation, stressing the importance of the blessing and curse contingent upon obedience to the legislation both in the present and in the future.[208]

- A: The blessing and curse in the present renewal of the covenant (Deuteronomy 11:26–28)

- B: The blessing and curse in the future renewal of the covenant (Deuteronomy 11:29–32)

- C: The specific legislation (Deuteronomy 12:1–26:19)

- B1:The blessing and curse in the future renewal of the covenant (Deuteronomy 27:1–26)

- B: The blessing and curse in the future renewal of the covenant (Deuteronomy 11:29–32)

- A1:The blessing and curse in the present renewal of the covenant (Deuteronomy 28:1–29:1)

Deuteronomy chapter 26

Professor Robert A. Oden, formerly of Dartmouth College, compared Deuteronomy 26:5–9, which he dated to 1100 BCE, in which he identified three themes (1) an ancient Patriarch Jacob, (2) the Exodus from Egypt, and (3) the conquest of the Land of Israel, to Nehemiah 9, which he dated to the 4th century BCE, in which he identified six themes, (1) creation, (2) the Patriarch Abraham, (3) a massively expanded Exodus story, (4) Moses and the reception of the Law, (5) wandering and rebelling in the Wilderness, and (6) the conquest. Oden identified the shape of the current Hebrew Bible with the Nehemiah outline.[209]

Reading the confessional recital in Deuteronomy 26:5, "A wandering Aramean was my father," Professor John Bright of Union Theological Seminary, Richmond, (now Union Presbyterian Seminary) in the mid-20th-century wrote that a tradition so deeply rooted was unlikely to be without foundation. Bright concluded that Israel's ancestors and those of the later Arameans were of the same ethnic and linguistic stock, and therefore it was not without reason that Israel could speak of her father as "a wandering Aramean."[210]

Deuteronomy chapter 27

Dr. Nathan MacDonald of St John's College, Cambridge, reported some dispute over the exact meaning of the description of the Land of Israel as a "land flowing with milk and honey," as in Exodus 3:8 and 17, 13:5, and 33:3, Leviticus 20:24, Numbers 13:27 and 14:8, and Deuteronomy 6:3, 11:9, 26:9 and 15, 27:3, and 31:20, MacDonald wrote that the term for milk (Hebrew: חָלָב, chalav) could easily be the word for "fat" (Hebrew: חֵלֶב, chelev), and the word for honey (Hebrew: דְבָשׁ, devash) could indicate not bees' honey but a sweet syrup made from fruit. The expression evoked a general sense of the bounty of the land and suggested an ecological richness exhibited in a number of ways, not just with milk and honey. MacDonald noted that the expression was always used to describe a land that the people of Israel had not yet experienced, and thus characterized it as always a future expectation.[211]

Professor James Kugel of Bar Ilan University noted that Deuteronomy shares certain favorite themes with Wisdom literature, as, for example, when Deuteronomy 19:14 and 27:17 prohibit moving boundary marks, a very specific offense also mentioned in Proverbs 22:28 and 23:10, as well as in ancient Egyptian wisdom texts (as well as Hosea 5:10). Kugel concluded that the Deuteronomist was closely connected to the world of wisdom literature.[212]

Deuteronomy chapter 28

Noting that the array of curses in Deuteronomy 28:1–69 dwarf the catalogue of blessings preceding them, the 20th century Reform Rabbi Gunther Plaut argued that this imbalance should not be surprising, for specific negative commandments far outnumber specific positive ones in the Torah, and forbidden behaviors were generally more common in law codes. Plaut taught that the Torah promises and threatens based on the realistic assumption that, while pure love of God and the commandments is the highest rung, such devotion for its own sake can be scaled only by the very few, while the majority will need earthly rewards and punishments held up before their eyes. Plaut reported general scholarly agreement that the vassal treaties of the Assyrian King Esarhaddon influenced these curses. Noting that in the Assyrian model, the suzerain lays down conditions and states what he will do if the vassal complies or fails to comply, Plaut concluded that the Torah's adoption of this treaty form can be seen as part of the Torah's ever-present view of Israel as a covenanted community.[213]

Professor Gerhard von Rad of Heidelberg University in the mid-20th-century argued that the section of curses attracted gradual amplifications after the catastrophe of the exile of 587 BCE. Von Rad saw the original set of curses in Deuteronomy 28:16–25a and 43–44, followed by a formal conclusion and summing up in Deuteronomy 28:45f.[214]

Deuteronomy chapters 28 and 29

In some Biblical translations, chapter 28 of Deuteronomy ends with Deuteronomy 28:69, "These are the words of the covenant which the Lord commanded Moses to make with the children of Israel in the land of Moab, beside the covenant which He made with them in Horeb,"[215] reading therefore that the covenant made or renewed at Moab was the one detailed in the preceding chapters of Deuteronomy. In the majority of modern texts, however, these words form verse 1 of chapter 29. Charles Ellicott argued that the Hebrew Bibles which "add this verse to the previous chapter, and begin Deuteronomy 29 at the second verse . . . cannot be right in so doing. For though the pronoun 'these' in Hebrew has nothing to determine whether it belongs to what precedes or to what follows, yet the context shows that the covenant is described in Deuteronomy 29, not in Deuteronomy 28."[216] Similarly, John Gill argued that the words of the covenant are "not what go before, but follow after, in the next chapters, to the end of the book."[217]

In critical analysis

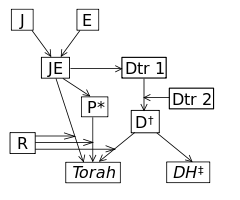

Some scholars who follow the Documentary Hypothesis find evidence of three separate sources in the parashah. Professor Richard Elliott Friedman, of the University of Georgia, attributed Deuteronomy 26:1–15 to the original Deuteronomistic law code (Dtn). He attributed Deuteronomy 26:16–28:35, 28:38–62, and 28:69–29:8 to the first, Josianic edition of the Deuteronomistic history. And he attributed Deuteronomy 28:36–37 and 28:63–68 to the second, exilic edition of the Deuteronomistic history.[218]

Commandments

According to Maimonides and Sefer ha-Chinuch, there are 3 positive and 3 negative commandments in the parashah.[219]

- To make the declaration on bringing the first fruits[220]

- To make the tithe declaration[221]

- Not to eat the second tithe while unclean, even in Jerusalem, until it has been redeemed[222]

- Not to eat the second tithe while mourning[222]

- Not to spend redemption money of the second tithe for anything but food and drink[222]

- To imitate God's good and upright ways[223]

In the liturgy

The Passover Haggadah, in the magid section of the Seder, quotes and interprets Deuteronomy 26:5–8.[224]

The Haggadah interprets the report of Deuteronomy 26:5, often translated as "a wandering Aramean was my father," to mean instead that Laban the Aramean tried to destroy Jacob.[225] Next, the Haggadah cites Genesis 47:4, Deuteronomy 10:22, Exodus 1:7, and Ezekiel 16:6–7 to elucidate Deuteronomy 26:5.[226] The Haggadah quotes Genesis 47:4 for the proposition that the Israelites had sojourned in Egypt.[227] The Haggadah quotes Deuteronomy 10:22 for the proposition that the Israelites started few in number.[228] The Haggadah quotes Exodus 1:7 for the proposition that the Israelites had become "great" and "mighty."[229] And the Haggadah quotes Ezekiel 16:6–7 to elucidate the report in Deuteronomy 26:5 that the Israelites had nonetheless become "numerous."[230]

Next, the Haggadah cites Exodus 1:10–13 to elucidate the report in Deuteronomy 26:6 that "the Egyptians dealt ill with us [the Israelites], and afflicted us, and laid upon us hard bondage."[231] The Haggadah quotes Exodus 1:10 for the proposition that the Egyptians attributed evil intentions to the Israelites or dealt ill with them.[232] The Haggadah quotes Exodus 1:11 for the proposition that the Egyptians afflicted the Israelites.[233] And the Haggadah quotes Exodus 1:13 for the proposition that the Egyptians imposed hard labor on the Israelites.[234]